An old Chinese saying goes, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” To paraphrase the Chinese, a journey of a thousand names begins with a single one: yours. If you are just starting your genealogy, with or without the Internet, the process is simple, if endlessly fascinating. This chapter will help you understand that process.

Organize from the Beginning

Friends often call to ask me, “Okay, I want to start my genealogy. What do I do?” The process of genealogy has these basic steps: Look at what you already know, record it, decide what you need to know next, research and query to track that information, analyze the new data, and then do it all again.

Experienced genealogists are more than willing to help the beginner. Longtime online genealogist Pat Richley-Erickson, also known as DearMYRTLE, has a lot of great advice on her site, www.dearmyrtle.com. Here are what she feels are the important points for the beginner: Just take it one step at a time, and devise your own filing system.

Don’t let the experts overwhelm you. Use the Family History Library’s Research Outline for the state/county where your ancestors came from. They can get you quickly oriented to what’s available and what has survived that might help you out.

Don’t invent your own genealogy program. Instead, choose one of the commercially available ones. Only use a GEDCOM-compatible software program, because it is the generic way of storing genealogy data. This way, you can import and export to other researchers with common ancestors in the future.

That’s the “what” to do, and soon we’ll look at that more closely.

“How” to do it includes these two basic principles: document and back up.

From the start, keep track of what you found, where you found it, and when. Even if it’s as mundane as “My birth certificate, in the fireproof box, in my closet, 2014,” record your data and sources. Sometimes, genealogists forget to do that and find themselves retracing their steps like a hiker lost in the woods. Backing up your work regularly is as important as recording your sources. Both of these topics will be covered in more detail in this chapter.

Your System

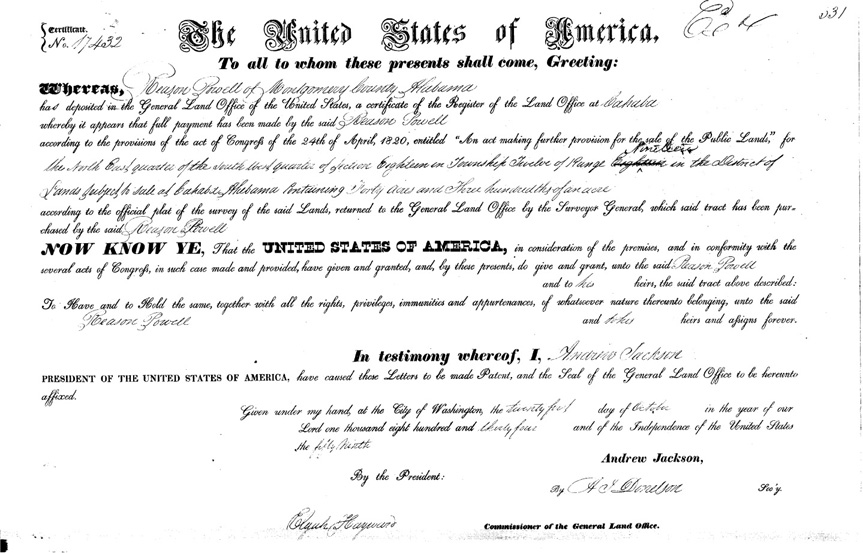

Software choices are covered in Chapter 2, where you will see how modern genealogy programs help you to do this. However, remember the good old index card (see Figure 1-1)? These can be useful to record data you find in a library, a friend’s book, or even an interview with older relatives until you can get back to your computer.

FIGURE 1-1. A sample index card with page numbers indicated for the data collected. The name of the book is written on the back.

The handwritten index card also serves as a backup, which brings us to the second most important thing: Back up your data. For most of this book, I assume you are using a computer program to record and analyze your data, but even if you are sticking to good old paper, typewriter, and pencils, as my fourth cousin Jeanne Hand Henry, CG, does, back that up with photocopies. Back up your computerized data in some way: external hard drive, flash drives, or online storage sites (see the following box) are all options, but you must back up. Grace happens, but so does other stuff, like hurricanes, wildfires, and hard drive crashes.

Many genealogists believe that using a good genealogy program with a feature to record sources is the way to go. Paper sources can be scanned into digital form for these programs. (You can also store paper documents in good old-fashioned filing cabinets.) Remember to keep a record of all your research findings, even those pieces of information that seem unrelated to your family lines. Some day that data may indeed prove pertinent to your family, or you may be able to pass it on to someone else. Even if you decide to do the bulk of your research on a computer, you might still need some paper forms to keep your research organized. The following box lists some websites where you can find forms to use as you research censuses and other records so that you can document your findings and sources. There’s more about documentation later in this chapter.

Good Practices

To begin your genealogy, begin with yourself. Collect the information that you know for certain about yourself, your spouse, and your children. The data you want are birth, marriage, graduation, and other major life milestones. The documentation would ideally be the original certificates; such documents are considered primary sources. Photographs with the people in them identified and the date on the back can also be valuable.

Such documents are considered primary sources because they reflect data recorded close to the time and place of an event.

Pick a Line

The next step is to pick a surname to pursue. As soon as you have a system for storing and comparing your research findings, you are ready to begin gathering data on that surname. A good place to begin is interviewing family members—parents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and in-laws. Ask them for stories, names, dates, and places of the people they knew. Ask whether some box in the attic or basement might have a file of old documents: deeds, marriage licenses, naturalization papers, family bibles, and so on. A good question to ask at this point is whether any genealogy of the family has been published. Understand that such a work is still a secondary source, not a primary source. If published sources have good documentation included, you might find them a great help.

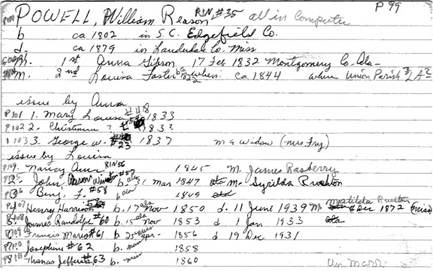

Visit a Family History Center (FHC) and the FamilySearch site (www.familysearch.org), which has indexes to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints family History Library and access to the new FamilySearch site. This site has data uploaded by members of the church, as well as other genealogists, and extractions of original records, such as marriages, births, deaths, and census records. In Figure 1-2 is my grandparents’ marriage license as an example.

FIGURE 1-2. When possible, get documents to back up what you’re told. Family bibles, old newspaper clippings, diaries, wills, licenses, and letters can help here.

Adventures in Genealogy

Family legend can be a good starting place, but don’t accept what you hear at face value. I will give you an example from my own experience.

When my husband and I were dating, his family’s stories fascinated me. One is that his mother is descended from Patrick Henry’s sister, who settled in Kentucky soon after the Revolutionary War. Her Logsdon line was also said to be descended from a Revolutionary War hero. T. W. Crowe, Mark’s paternal grandfather, said his grandmother was full-blooded Cherokee.

The maternal line was researched and proven by Mark’s mother as part of the Daughters of the American Revolution project. Documentation galore helped provide the proof. But the paternal line was more problematic. While T. W. Crowe had some physical characteristics of Native Americans, as does my husband, no one in the family had documents to help me prove the connection. Had I been able to prove it, our children might have been eligible for scholarships and special education in Native American history. After we married and had children, I asked T. W. for the details that would qualify our children for this, but he would not discuss it with me. Indeed, the more I pressed for information, the more reticent T. W. became, and he died in 1994 without my finding the evidence. However, I have kept searching. Using the old family bible, which has a record of T. W.’s parents, I am still looking at census records, wills, deeds, and other data to see whether I can prove one of them was of Cherokee descent.

A relative told me that T. W., in effect, had been testing me: The Native American grandmother was something not talked about in his generation or the one before his. By telling me what was considered a “family scandal,” T. W. was trying to find out if I would be scared off from dating his grandson. The poor man had no idea he had chosen to test me with something that would get my genealogy groove on!

Which brings up this point: While all family history is fascinating to those of us who have been bitten by that genealogy bug, to others, some family history is, at best, a source of mixed emotions and, at worst, a source of shame and fear. You must be prepared for some disagreeable surprises and even unpleasant reactions.

References to Have at Hand

As you post queries, send and receive messages, read documents online, and look at library card catalogs, you will need some reference books at your fingertips to help you understand what you have found and what you are searching for. Besides a good atlas and perhaps a few state or province gazetteers (a geographic dictionary or index), having the following books at hand will save you a lot of time in your pursuit of family history:

• The Handy Book for Genealogists United States of America (9th Edition) by George B. Everton, editor (Everton Publishers, 1999). Pat Richley-Erickson, aka DearMYRTLE, says she uses this reference book about 20 times a week. This book has information such as when counties were formed; what court had jurisdiction where and when; listings of genealogical archives, libraries, societies, and publications; dates for each available census index; and more.

• The Source A Guidebook of American Genealogy by Sandra H. Luebking (editor) and Loretto D. Szucs (Ancestry Publishing, 2006) or The Researcher’s Guide to American Genealogy by Val D. Greenwood (Genealogical Publishing Company, 2000). These are comprehensive, how-to genealogy books. Greenwood’s is a little more accessible to the amateur, whereas Luebking’s is aimed at the professional certified genealogist, but still has invaluable information on family history research.

• Cite Your Sources A Manual for Documenting Family Histories and Genealogical Records by Richard S. Lackey (University Press of Mississippi, 1986) or Evidence! Citation & Analysis for the Family Historian by Elizabeth Shown Mills (Genealogical Publishing Company, 1997). These books help you document what you found, where you found it, and why you believe it. The two books approach the subject differently: The first is more amateur-friendly, whereas the second is more professional in approach.

Analyze and Repeat

When you find facts that seem to fit your genealogy, you must analyze them, as noted in the section “How to Judge,” later in this chapter. When you are satisfied that you have a good fit, record the information and start the process again.

Success Story: A Beginner Tries the Shotgun Approach

Success Story: A Beginner Tries the Shotgun Approach

My mother shared some old obituaries with me that intrigued me enough to send me on a search for my family’s roots. I started at the ROOTSWEB site with a metasearch, and then I sent e-mails to anyone who had posted the name I was pursuing in the state of origin cited in the obituary. This constituted over 50 messages—a real shotgun approach. I received countless replies indicating there was no family connection. Then, one day, I got a response from a man who turned out to be my mother’s cousin. He had been researching his family line for the last two years. He sent me census and marriage records, even a will from 1843 that gave new direction to my search.

In pursuing information on my father, whom my mother divorced when I was two months old (I never saw him again), I was able to identify his parents’ names from an SS 5 (Social Security) application and, subsequently, track down state census listings containing not only their birth dates, but also the birth dates of their parents—all of which has aided me invaluably in the search for my family’s roots. Having been researching only a short while, I have found the online genealogy community to be very helpful and more than willing to share information with newbies like myself. The amount of information online has blown me away.

—Sue Crumpton

Know Your Terms

As soon as you find information, you are going to come across terms and acronyms that will make you scratch your head. Sure, it’s easy to figure out what a deed is, but what’s a cadastre? What do DSP and LDS mean? Is a yeoman a sailor or a farmer?

A cadastre is a survey, a map, or some other public record showing ownership and value of land for tax purposes. DSP is an abbreviation for a phrase that means “died without children.” LDS is shorthand for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or the Mormons. And finally, a yeoman can designate a farmer, an attendant/guard, or a clerk in the Navy, depending on the time and place. Most of this is second nature to people who have done genealogy for more than a couple of years, but beginners often find themselves completely baffled. And then there are the calendars—Julian, Gregorian, and French Revolutionary—which means that some records have double dates, or a single date that means something different from what you think it should.

No, wait—don’t run screaming into the street! Just try to get a handle on the jargon. I have included a glossary at the end of this book with many expressions.

Sources and Proof

Most serious genealogists who discuss online sources want to know if they can “trust” what they find on the Internet. For example, the original Mayflower passenger list has been scanned in at Caleb Johnson’s site, www.mayflowerhistory.com. Would you consider this a primary source? A secondary source? Or simply a good clue? This is a decision you must make for yourself as you start climbing that family tree.

Some genealogists get annoyed with those who publish their genealogy data on the Internet without citing each source in detail. Once, when I was teaching a class on how to publish genealogy on the Internet at a conference, a respected genealogist took me to task over dinner. “Webpages without supporting documentation are lies!” she insisted. “You’re telling people to publish lies, because if it’s not proven by genealogical standards, it might not be true!”

And in 2012, many online genealogists were very concerned with the difference between evidence and proof. Websites, books, and long discussions raged across the Web about definitions and methodologies and techniques to the point almost of obsession.

Here, dear reader, I have to admit I have a more relaxed attitude. You do have to read carefully, you do have to get as close as possible to the original record, and you do have to realize that information posted by someone on the Web may well be inaccurate. However, I do not think the information on the Web is any more or less accurate than information in your library in physical form. And you can’t let being careful get in the way of the sheer joy of finding a clue, an answer, or a fourth cousin you never knew about before.

Please be aware that many respected professional genealogists disagree with me. I say this as a hobbyist, as someone who simply enjoys the research process and the puzzle solving involved with genealogy. I am not someone trying to impress anyone with my family history, and no important issue hangs on whether I have managed to handle the documents myself. If I wanted to register with the College of Arms or inherit a fortune from some estate, then the original documents would be absolutely necessary. If I just want to know what my great-grandfather did for a living, reading a census taker’s handwriting on the Internet will do. And it must be said, secondary sources are much easier to find than primary sources. The main value of these secondary sources on the Internet is in the clues as to where and when primary sources were created. Simply reading that a source such as a diary, a will, or a tax document exists can be a breakthrough.

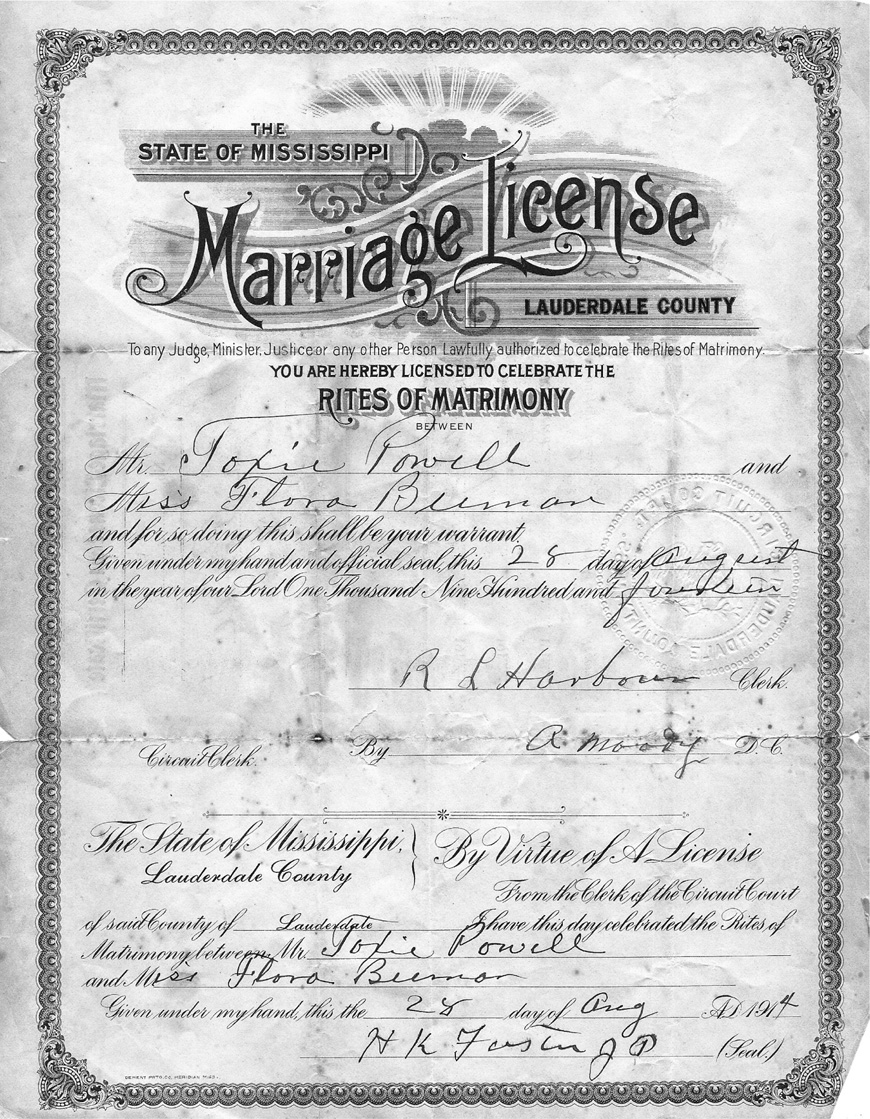

Some primary materials are online, however. People and institutions are scanning and transcribing original documents onto the Internet, such as the Library of Virginia and the National Park Service. Volunteers are indexing census records and marriage records at https://familysearch.org/indexing/. You can also find online a growing treasure trove of indexes of public vital records and scanned images of Government Land Office land patents (www.glorecords.blm.gov—see in Figure 1-3).

FIGURE 1-3. You can view original land grants, such as this one for my ancestor Reason Powell, and order certified copies online. This sort of original record is invaluable in family history research.

The online genealogist can find scanned images of census records at both the U.S. Census Bureau site (www.census.gov) and volunteer projects, such as the USGenWeb Digital Census Project (www.rootsweb.com/census/).

Therefore, I still believe in publishing and exchanging data over the Internet as long as you remember to analyze what you find and make reasonable conclusions, not fanciful assumptions.

How to Judge

Be aware that just because something is on a computer, this doesn’t make it infallible. Garbage in, garbage out has always been the immutable law of computing. The criteria for the evaluation of resources on the Web must be the same criteria you would use for any other source of information. With this in mind, ask yourself the following questions when evaluating an online genealogy site.

Who Created It?

You can find all kinds of resources on the Internet—from libraries, research institutions, and organizations such as the National Genealogical Society (NGS), to government and university resources. Sources such as these give you more confidence in their data than, say, resources from a hobbyist, or even information from an online query. Publications and software companies also publish genealogical information, but you must read the site carefully to determine whether they’ve actually researched this information or simply posted whatever their customers threw at them. Finally, you can find tons of “family traditions” online. And although traditions usually have a grain of truth to them, at the same time, they are usually not unvarnished.

How Long Ago Was It Created?

The more often a webpage is updated, the better you can feel about the data it holds. Of course, a page listing the census for a certain county in 1850 needn’t be updated every week, but a pedigree put online should be updated as the author finds more data.

Where Does the Information Come From?

If the page in question doesn’t give any sources, you’ll want to contact the page author to acquire the necessary information. If sources do exist, of course, you must decide if you can trust them.

In What Form Is the Information?

A simple GEDCOM published as a webpage can be useful for the beginner, but ideally, you want an index to any genealogical resource, regardless of form. If a site has no search function, no table of contents, or no document map (a graphic leading you to different parts of the site), it is much less useful than it could be.

How Well Does the Author Use and Define Genealogical Terms?

Does the author clearly know the difference between a yeoman farmer and a yeoman sailor? Does the author seem to be knowledgeable about genealogy? Another problem with online pages is whether the author understands the problems of dates—both badly recorded dates and the 1752 calendar change. There are sites to help you with calendar problems.

Does the Information Make Sense Compared to What You Already Know?

If you have documentary evidence that contradicts what you see on a webpage, treat it as you would a mistake in a printed genealogy or magazine: Tell the author about your data and see whether the two versions can be reconciled. This sort of exchange, after all, is what online genealogy is all about! For example, many online genealogies have a mistake about one of my ancestors because they didn’t stop to analyze the data and made erroneous assumptions.

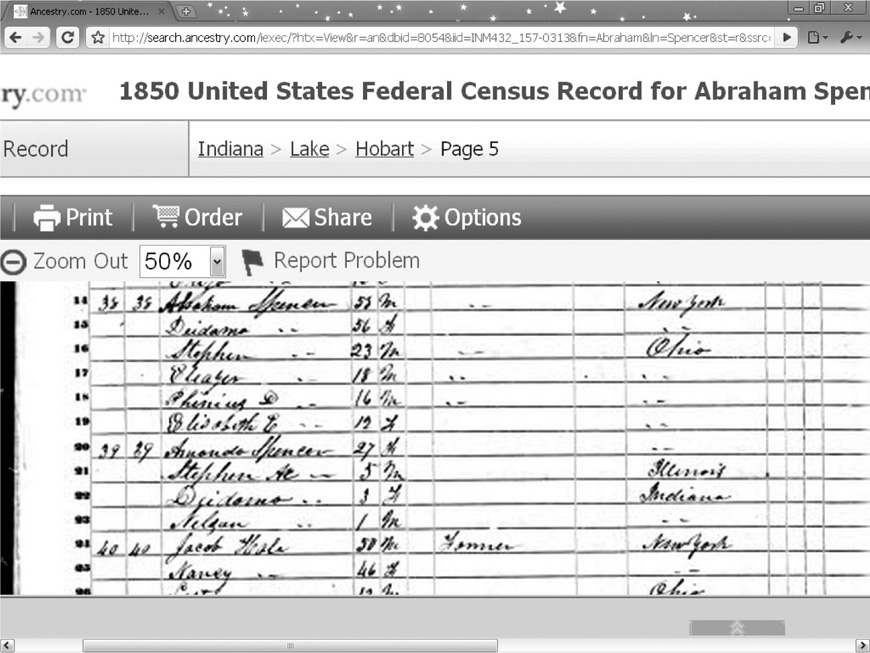

In Figure 1-4, you can see a transcription of the 1850 Census of Lake County, Indiana.

FIGURE 1-4. Census records sometimes need careful study and interpretation.

The column labeled HN is for household numbered in order of visitation; the column labeled FN is for families numbered in order of visitation. You can see Abraham Spencer (age 58) and his wife Diadama (age 56; her name is misspelled on the census form) have children Stephen through Elisabeth, and underneath are Amanda, age 27, and then three children under the age of 5. Some genealogies I have found on the Web assume that Amanda and the following children are also offspring of Abraham and Diadama, but if you look at the ages and how the families are listed—with Amanda and the younger children under the youngest of Abraham and Diadama’s children—you see this doesn’t make sense. On the other hand, if you were to look at the mortality schedule for the county for that year, you would see that Orsemus Spencer (Amanda’s husband and Abraham’s son) died in February before the census taker arrived in October. Amanda and her children moved in with her in-laws after her husband’s death. The three youngest ones are part of the household, but they aren’t Abraham Spencer’s children; they are his grandchildren.

With this in mind, becoming familiar with the National Genealogical Society’s Standards for Sharing Information with Others, as shown in Appendix A, would help. Judge what you find on the Internet by these standards. Hold yourself to them as you exchange information, and help keep the data on the Internet as accurate as possible. After you have these standards firmly in mind, a good system to help you track what you know, how you know it, and what you don’t know, as well as the surnames you need, is simply a matter of searching for the facts regarding each individual as you go along.

Standards of Genealogical Research

Genealogy is a hobby for most of us, and we do it for fun. The average genealogist is not doing this for fame and fortune, but because of an insatiable curiosity about the people who came before us. Given that, this little section may seem a bit too serious, even “taking all the fun out of it.” Still, I believe that if you approach this hobby with the right attitude and care, it will be more rewarding than if you just dive in without giving a thought to the best practices and ethics. Despite the fact that there are no official “rules” to this when you are a hobbyist, following guidelines and standards can, in the end, make your experience easier and more enjoyable.

As mentioned previously, in the appendixes to this book you will find the latest standards and guidelines from the National Genealogical Society (www.ngsgenealogy.org), and I suggest you study them. Though you can (and should) take many excellent courses in genealogy, if you review and understand these documents first, you will be better prepared to proceed on your family history quest in the best manner.

Briefly, the NGS standards and guidelines emphasize these points:

• Do not assume too much from any piece of information.

• Know the differences between primary and secondary sources.

• Keep careful records.

• Give credit to all sources and other researchers when appropriate.

• Treat original records and their repositories with respect.

• Treat other researchers, the objects of your research, and especially living relatives with respect.

• Avail yourself of all the training, periodicals, literature, and organizations you can afford in time and money. Joining the NGS is a good first step!

• And finally, mentor other researchers as you learn more yourself.

Another good outline to the best way to practice genealogy is the Board for Certification of Genealogists Code of Ethics and Conduct on their website at www.bcgcertification.org/aboutbcg/code.html. This is also a guide to choosing a professional, should you decide to get some help on your genealogy along the way!

How to Write a Query

Genealogy is a popular hobby, and lots of people have been pursuing it for a long time. When you realize that, it makes sense to first see whether someone else has found what you need and is willing to share it. Your best tool for this is the query.

A query, in genealogy terms, is a request for data, or at least for a clue where to find data on a specific person. Queries may be sent to one person in a letter or in an e-mail to the whole world (in effect). You can also send queries to an online site, a magazine, a mailing list, or another forum that reaches many people at once.

Writing a good query is not hard, but you do have to use certain rules for it to be effective. Make the query short and to the point. Don’t try to solve all your genealogical puzzles in one query; zero in on one task at a time.

You must always list at least one name, at least one date or time period, and at least one location to go with the name. Do not bother sending a query that does not have all three of these elements, because no one will be able to help you without a name, a date, and a place. If you are not certain about one of the elements, follow it with a question mark in parentheses, and be clear about what you know for sure as opposed to what you are trying to prove.

Here are some style points to keep in mind:

• Use all capital letters to spell every surname, including the maiden name and previous married names of female ancestors.

• Include all known relatives’ names—children, siblings, and so on.

• Use complete names, including any middle names, if known.

• Proofread all the names.

• Give complete dates whenever possible. Follow the format DD Month YYYY, as in 20 May 1865. If the date is uncertain, use “before” or “about” as appropriate, such as “Born c. 1792” or “Died before October 1850.”

• Proofread all the dates for typos; this is where transpositions can really get you!

• Give town, county, and state (or province) for North American locations; town, parish (if known), and county for United Kingdom locations; and so on. In other words, start with the specific and go to the general, including all divisions possible.

• If you are posting your query to a message board, it is helpful to include the name, the date, and, if possible, migration route using > to show the family’s progress.

• Finally, include how you wish to be contacted. For a letter query or one sent to a print magazine, you will want to include your full mailing address. For online queries, you want to include at least an e-mail address or your user name on that site.

Here’s a sample query for online publication:

Query: Crippen, 1794, CT>MA>VT>Canada

I need proof of the parents of Diadama CRIPPEN born 11 Sept 1794 in (?), NY. I believe her father was Darius CRIPPEN, son of Samuel CRIPPEN, and her mother was Abigail STEVENS CRIPPEN, daughter of Roger STEVENS, both from CT. They lived in Egremont, Berkshire County, MA and Pittsfield, Rutland County, VT before moving to Bastard Township, Ontario, Canada. I will exchange information and copying costs. [Here you would put your regular mail address, e-mail address, or other contact information.]

As you can see, this query is aimed at one specific goal: the parents of Diadama. The spelling matches the death notice that gave the date of birth—a secondary source—but because it is close to the actual event, it’s acceptable to post this with the caveat “I believe.” It has one date, several names, several places, and because this one is going online, a migration trail in the subject line (CT>MA>VT>Canada). If the author knew Diadama’s siblings for certain, they would be in there, too. When you have posted queries, especially on discussion boards and other online venues, check back frequently for answers. If the site has a way to alert you by e-mail when your posting gets an answer, be sure to use it. Also, read the queries from whatever source you have chosen to use, and search query sites for your surnames. As you can see from the example, queries themselves can be excellent clues to family history data!

Documentation

Document everything you find. When you enter data into your system, enter where and when you found it. Like backups of your work, this will save you countless hours in the long run.

A true story: At the beginning of her genealogy research in the late 1960s, my mother came across a volume of biographies for a town in Kansas. This sort of book was common in the 1800s. Everyone who was “someone” in a small town would contribute toward a book of history of the town. Contributors were included in the book, sometimes with a picture, and the biography would be a timeline of their lives up to the publication of the book, emphasizing when the family moved to town and their importance to the local economy. One of these biographies was of a man named Spencer and included a picture of him. He looked much like her own grandfather, but the date was clearly too early to be him. Still, she photocopied it, just in case. However, she didn’t photocopy the title page or make a note of where she had seen the book, which library, which town, and so forth.

Fast-forward 15 years to the early 1980s. At this point, my mother is in possession of much more data, and in organizing things, came across the photocopy. Sure enough, that biography she had found years before is of her grandfather’s grandfather; she had come across enough primary sources (birth certificates, church records, and so on) to know this. And now, she knew this secondary source had valuable information about that man’s early life, who his parents were, and who his in-laws were. However, all she had was the page, with no idea of how to find the book again to document it as a source! It took days to reconstruct her research and make a guess as to which library had it. She finally did find it again and documented the source, but it was quite tedious. Just taking an extra two minutes, years before, would have saved a lot of time!

Backup

Back up your data. I’m going to repeat that in this book as often as I say, “Document your sources.” Documentation and backup are essential. On these two principles hang all your effort and investment in genealogy. Hurricanes happen. Fire and earthquakes do, too. Software and hard drives fail for mysterious reasons. To have years of work gone with the wind is not a good feeling.

If you are sticking to a paper system, make photocopies and keep them offsite—perhaps at your cousin’s house or a rental storage unit. More and more people are using “the cloud” or online backup—that is, using someone else’s computer to hold your data files.

Online storage services are a convenient way to store offsite backup copies of critical information. Some services that are free until you reach some level of use are XDrive, box.net, Mozy, DropBoks, iBackup, eSnips, MediaMax, OmniDrive, openomy, and more. If you need more than the basic free space, they all offer additional storage, costing from $5 to $30 a month, depending on how much room you need. Several of these services will let you make some files available to other people while keeping other files secret and secure. Although all of them will work with both Macintosh and PC computers, some of them are picky about the web browser you use. Experiment with several of these services and find the one with the right fit for you. Then use it often!

Publishing Your Findings

Sooner or later, you’re going to want to share what you’ve found, perhaps by publishing it on the Internet. To do this, you need space on a server of some sort. Fortunately, your choices here are wide.

Most Internet service providers (ISPs) allot some disk space on their servers for their users. Check with your ISP to see how much you have. Many other sites offer a small amount of web publishing space for free, as long as you allow them to display an ad on the visitor’s screen. Just put “Free Web Space” in any search engine and you will come up with a current list.

Some software programs will put your genealogy database on the software publishers’ website, where it can be searched by others. Some websites, such as WorldConnect, let you post the GEDCOM of your data for searching in database form instead of in Hypertext Markup Language (HTML). Finally, genealogy-specific sites, such as ROOTSWEB and MyFamily.com, offer free space for noncommercial use in HTML format.

Some of the programs, however, don’t give you a choice of where you post your data. Some will post your data on a proprietary site. Once there, your data becomes part of the company’s database, which may be sold later. Simply by posting your data on the site, you give them permission to do this. There is quite a bit of discussion and debate about this privatization of publicly available data. Some say this will be the end of amateur genealogy, whereas others feel this is a way to preserve data that might be lost to disaster or neglect. It’s up to you whether you want to post to a site that reuses your data for its own profit.

In short, publishing on the Internet is doable, as well as enjoyable, but you have to do it thoughtfully. By publishing at least some of your genealogy on the Internet, you can help others looking for the same lines. But don’t get carried away—you want to publish data only on deceased people, or publish only enough data to encourage people to write you with their own data and exchange sources. Don’t publish data on living people.

Success Story: Finding Cousins Across the Ocean

Success Story: Finding Cousins Across the Ocean

After ten years of getting my genealogy into a computer, I finally got the nerve to “browse the Web,” and to this day I don’t know how I got there, where I was, or how to get back there—but I landed on a website for French genealogists. I can neither read nor speak French. I bravely wrote a query in English: “I don’t read or speak French, but I am looking for living cousins descended from my ancestors ORDENER.” I included a short “tree” with some dates and my e-mail address. Well, within a couple of hours, I heard from an ORDENER cousin living in Paris, France. She did not know she had kin in America and had spent years hunting in genealogy and cemetery records for her great-great-grandfather’s siblings! She had no idea they had come to America in the 1700s and settled in Texas before it was a state of the Union. So, while I traded her hundreds of names of our American family, she gave me her research back to about 1570 France when the name was ORTNER! About four months later, another French cousin found me from that query on the Web. He did not know his cousin in Paris, so I was able to “introduce” him via e-mail. One of them has already come to Florida to meet us! What keeps me going? Well, when I reach a brick wall in one family, I turn to another surname. Looking for living cousins is a little more successful than looking for ancestors, but you have to find the ancestors to know how to go “down the line” to the living distant cousins! Genealogy is somewhat like a giant crossword puzzle—each time you solve a name, you have at least two more to hunt! You never run out of avenues of adventure—ever!

—Patijé Weber Mills Styers

Caveats

In discussing how to begin your genealogy project, we must consider the pitfalls. This chapter has touched briefly on your part in ethics and etiquette, and future chapters will expand on that. We must also consider the ethics of others, however, and be careful.

In the twenty-first century, genealogy is an industry. Entire companies are centered on family history research and resources. Not surprisingly, you will find people willing to take your money and give you little or nothing in return in genealogy, just as in any industry. Many of them started long before online genealogy became popular, and they simply followed when genealogists went online. “Halberts of Ohio” is one notorious example, a company that sold names from a phone book as “genealogy.”

Don’t believe anyone who wants to sell you a coat of arms or a crest for your surname. These are assigned to specific individuals, not general surnames. (Although a crest may be assigned to an entire clan in Ireland—the crest is the part above the shield.) A right to arms can only be established by registering a pedigree in the official records of the College of Arms. This pedigree must show direct male line descent from an ancestor who was granted a letter patent. You can also, under the right circumstances, apply through the College of Arms for a grant of arms for yourself. Grants are made to corporations as well as to individuals. For more details, go the college’s site: www.college-of-arms.gov.uk.

Always check a company’s name and sales pitch against sites that list common genealogy scams. For example, Cyndi Howells keeps on top of myths, lies, and scams in genealogy and has a good set of links to consumer protection sites, should you fall prey to one of them. Cyndi’s List Myths, Hoaxes, and Scams page is at www.cyndislist.com/myths. Kimberly Powell’s How to Identify & Avoid Genealogical Scams page (http://genealogy.about.com/od/basics/tp/scams.htm) gives a good set of steps to follow too.

If you feel you have been scammed, report it to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) at www.ftccomplaintassistant.gov/.

Wrapping Up

• Record your data faithfully. Back it up faithfully. These two things will save you a world of grief some day.

• To begin your genealogy project, start with yourself and your immediate family, documenting what you know. Look for records for the next generation back by writing for vital records, searching for online records, posting queries, and researching in libraries and courthouses. Gather the information with documentation on where, when, and how you found it. Organize what you have, and look for what’s needed next. Repeat the cycle.

• Beware of scams!