Chapter 1. The Tao of Dynamic Workflow

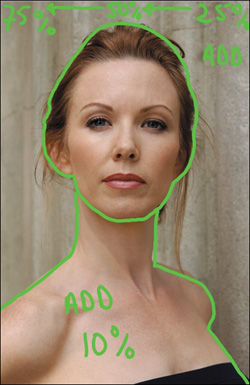

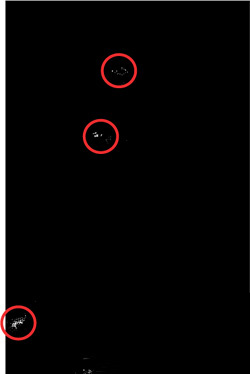

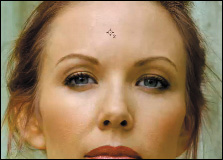

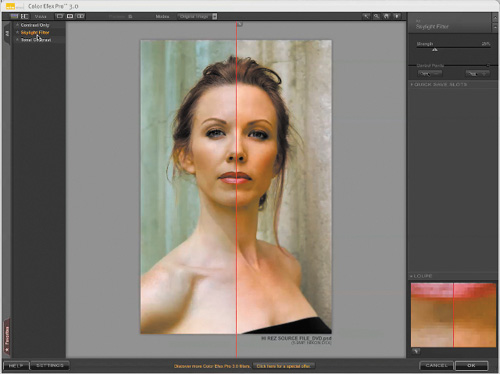

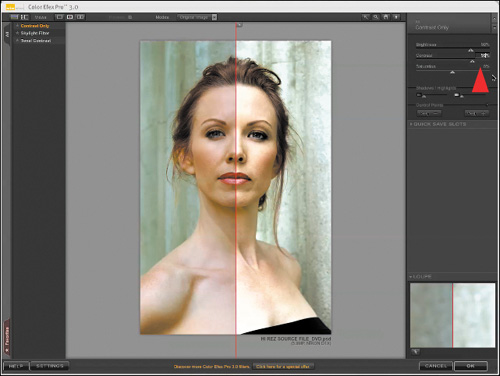

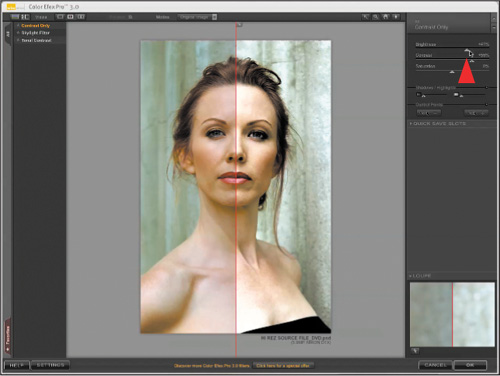

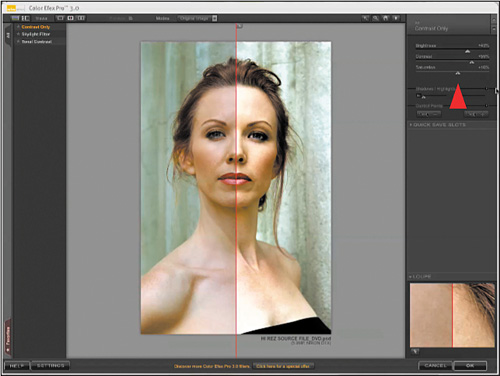

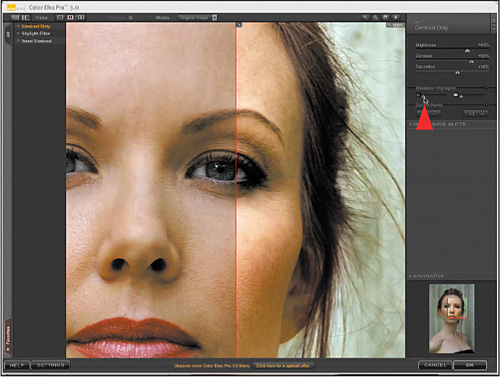

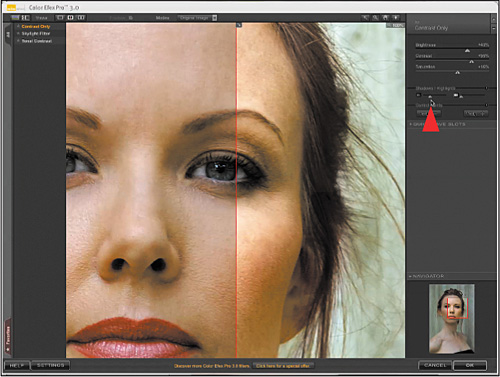

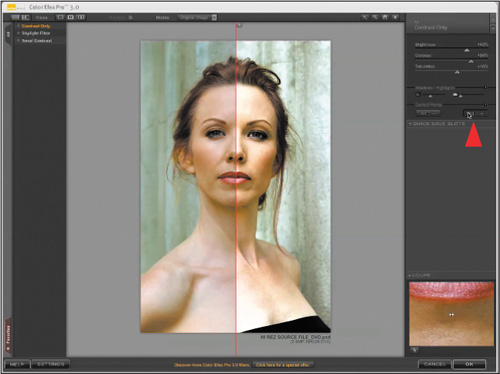

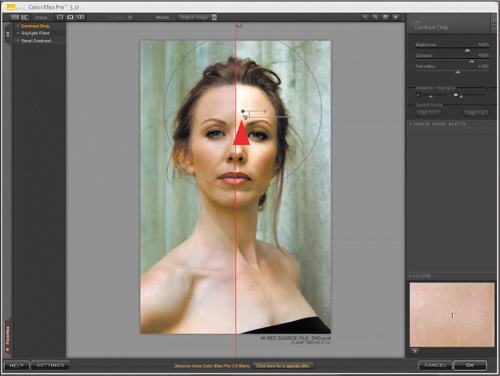

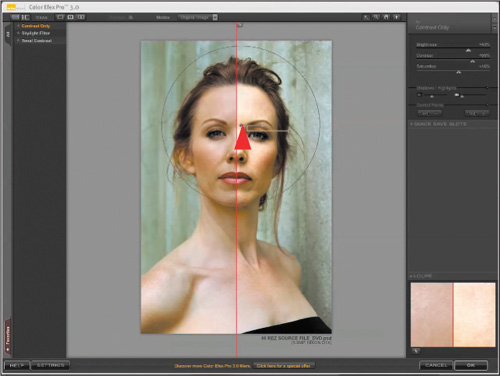

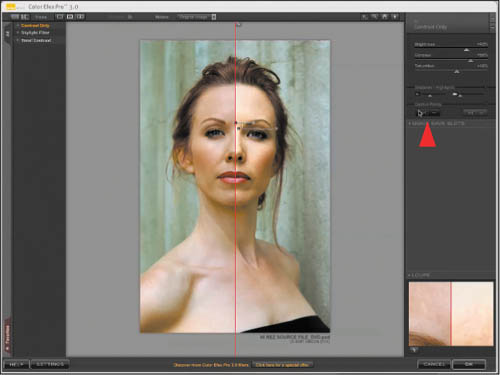

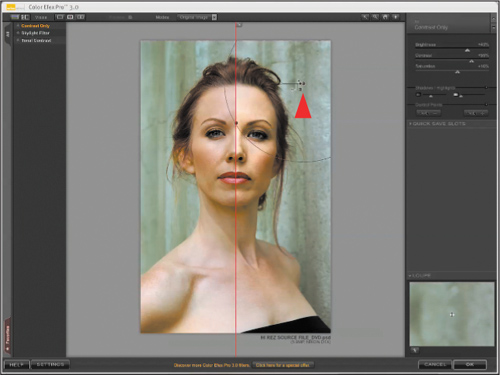

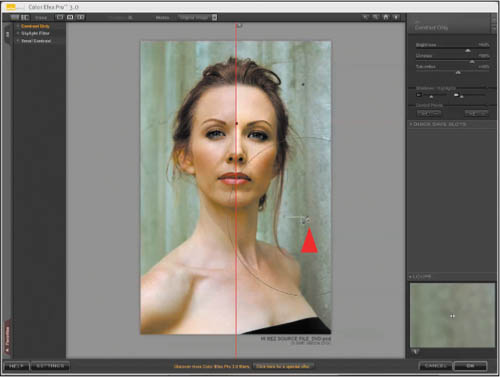

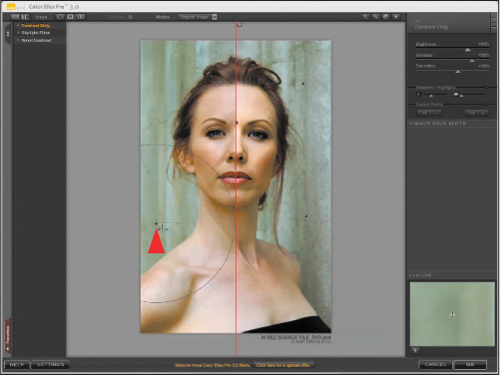

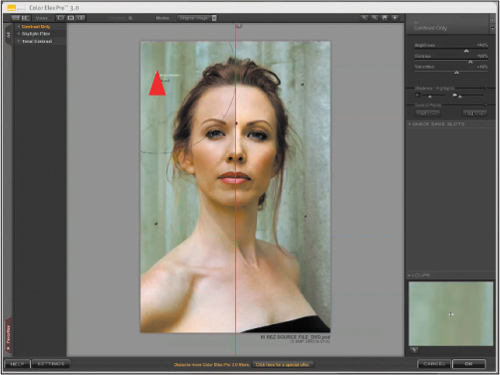

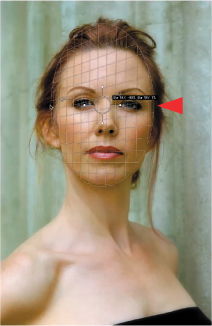

Figure 1.0.1. Before

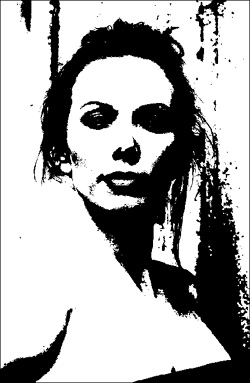

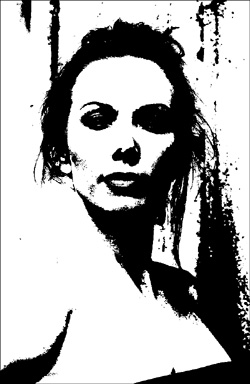

Figure 1.0.2. After

Practice doesn’t make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect. You first have to practice at practicing.

—Vince Lombardi

This chapter deals with how to analyze an image and develop a dynamic, image-specific workflow, so that you can achieve in the print, the image as you conceptualized it. I place special focus on image mapping and how to do basic lighting in Photoshop. I also take a broader look at how to approach images and think about them. This lesson is about learning how to practice at practicing and then about how to find the path to perfect practice.

Revisiting Shibumi: The Art of Perfect Practice

My wish for this book was to make each chapter reflect, as closely as possible, an actual workflow—not some idealized sequence. Because workflow is fluid, and books are static, Acme Educational allowed me to use their high resolution computer screen grabs (frames from their 1200×1600 QuickTime movie) as part of each lesson in this book. But because some of you learn better by reading, some by seeing, and some do best using both, if you wish, you can purchase all the lessons from this book as a video set at www.acmeeducational.com. Both this book and the Acme tutorial are designed to stand alone, but they are mutually supportive.

Of all the lessons in this book, “Shibumi: The Art of Perfect Practice,” is the one to which I return again and again. When I originally created the image that I have used in this lesson, I learned a lot of the things that eventually led to the creation of my first book, Welcome to Oz. But, perhaps the most important thing that I learned is that impossible is just an opinion.

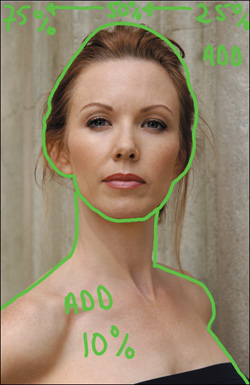

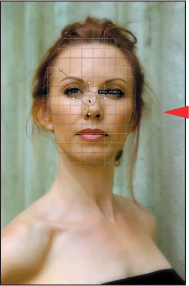

The image in this chapter is a picture of the actress Challen Cates from a photo shoot that I did in Los Angeles using a single piece of lighting gear, a 6′×3′ diffuser. Why a single piece of lighting gear? Simple—the lighting equipment I planned to use did not show up when I did. I had planned to use hot lights and reflectors, but when the lights did not show up, I was three hours away from my studio with only the diffuser that I had loaded, as an afterthought, into my assistant’s car. My choices were either to react to the situation and call it a day, or be proactive and go ahead with the shoot believing that by adapting and improvising, I would be able to achieve my original vision. Choosing to be proactive, I had my assistant hold the diffuser over Challen’s head so that she was evenly lit. Doing this would give me the best possible source file with which to work so that I could later light her properly in the computer. The techniques that I had to develop in order for me to achieve my original vision are the techniques that I want to share with you.

Note

Every image in this book marks a significant milestone in the development of my approach to creating images. Each represents a moment of discovery in which I found a new way to create, in print, what my eye had initially determined should be there.

I believe that it is best to approach Photoshop preemptively, to get it right in the camera, and that Photoshop is best used as an emery board and not a jackhammer. Even when the situation does not lend itself to getting it perfect, as in the case of the Challen Cates shoot, at the time of capture you should get as much right as possible.

In order to know how to get it right in the camera, which is the beginning of the process, you must understand the middle and end of the process as well. The middle of the process is the manipulation of the file in Photoshop and its end is the print, which is your voice, your vision.

This lesson will teach you how to analyze an image and optimize it. Image optimization is a process of refinement. First you make broad strokes that you later refine (what I call working from the global to the granular), removing everything that is not your vision, so all that remains is the image that you envisioned. You will also learn how to develop a dynamic, image-specific workflow so that you can achieve in the print the image as you conceptualized it. You will be able to do this because you will gain an understanding of how to maximize capture, so that manipulation of the file in Photoshop will result in the print that you wanted to achieve. Because of the circumstances of the Challen Cates shoot, the image that I had in my head when I captured it was nothing like the image I was forced to take—an image with almost no variation in light, dark, contrast, saturation, focus, or blur. I knew, however, that if I kept my initial vision in my head, using Photoshop, I could create those variations within that picture, so that it would be transformed into what I knew it should become.

IMPORTANT: Before You Begin This Lesson

If you have not downloaded the free plug-ins, the demo plug-ins, and source files from the download site for this lesson, as well as all the other files that are provided for the lessons in this book, go to: http://www.welcome2oz.com. All of the URLs that you need are located there, and you should do this before you go any further.

Note

All of the lessons have instructions on how to do them without the demo software, but when it comes to the free plug-ins (except in one instance), there is no alternative approach available in Photoshop. The reason for this is either that there is no way in Photoshop to accomplish what the plug-ins do, or that the plug-in does a better job. Also, the plug-ins are free with this book. One-hundred percent of my images see at least two of the plug-ins you now own. I highly recommend that you try them.

Each source file has two versions for all of the lessons in this book: one that contains all of the image maps that I created, and one that has only the source files. I urge you to use your own image maps, but they are best used if you have a tablet or pen-based display like I do. (I prefer a Wacom Cintiq or an Intuos 4 tablet.) If you have neither, or simply want to get right to the lesson, then use the source files with the image maps that I have provided.

The Secret of Dynamic Workflow

Workflow is a flexible series of steps that one follows to efficiently and accurately realize your vision.

—R. Mac Holbert

No two images are the same, so no two images will ever require the identical workflow, therefore, a standard workflow recipe does not exist. Some images are simply easier to work with than others, but before you begin, you may not know how much difficulty you will encounter. Your workflow must be flexible enough to accommodate any level of complexity.

Workflow is the operational aspect of a work procedure (in this case, producing a final image) and includes: how tasks are structured, their relative order, and how they are synchronized. A dynamic workflow is one in which you allow yourself mental flexibility when you work on an image. It is about figuring out how to process your file in order to create that which you hold in your mind’s eye. By approaching workflow dynamically, you not only gain total artistic control, even your file structure will be flexible, so that as technology and your skills improve, you can return to your files and re-interpret them.

A dynamic workflow is about making things as simple as possible, but no simpler, and working as quickly as possible, but no quicker. If an image is worthy enough to be worked on, then it is worth taking your time and care to create the image that realizes your vision. When you send an image out into the world, it has a life of its own, and if you did your job well, viewers will be moved. But you also have a life and should spend less of it using Photoshop.

To achieve a truly organized, dynamic workflow, you must be adaptable and open to improvisation. It is through such improvisational practice that you overcome obstacles. By practicing at practicing, you can find the way to engage in perfect practice, which is achieved when you unconsciously, and without effort, adapt and improvise in order to overcome obstacles. The Japanese call it “being in Shibumi.” This lesson is about learning how to be in Shibumi whenever and wherever you create.

Practicing What I Preach

From the time that I first created this image, I have grown as an artist, both aesthetically and technically. I have gained better understanding of the software now available, and of post-processing technology. I am still on my journey to understand light and how to replicate it, but I have more skills than I did when I first captured Challen’s image.

If you read the first version of Welcome to Oz, you will notice that my artistic core beliefs have not changed, but there have been some significant changes in the way I do things, as well as the way Challen’s image now looks. I believe that through the practice of practicing, you will discover that every experience is new (even reworking an old image) if you bring to that experience an openness to explore.

Setting Up Photoshop for a Non-Destructive Workflow

The negative is everything. The print is all.

—Ansel Adams

The finest images—more specifically, the finest prints—are actually about how well the file was managed, but logic suggests that you should know how the device that does the printing works and what you can do to manipulate it. The issue, however, is that the printer is a default device; you can turn it on and off, put ink in it, and put the paper of your choice into it. Because inkjet printing devices today are so stable, little can or needs to be done to them. High quality prints are produced long before setting up image sizing and making selections in the printer driver. It is your imaging software and what you do to your file that ultimately controls your printer. Your prints will more accurately reflect your photographic vision, if you understand your imaging software.

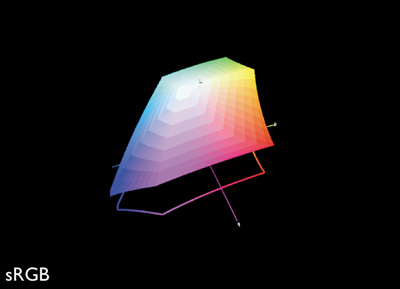

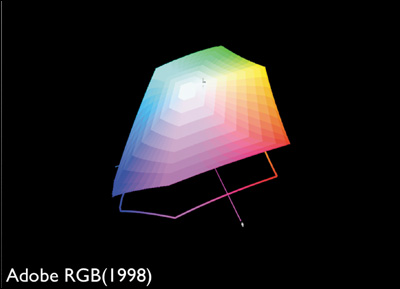

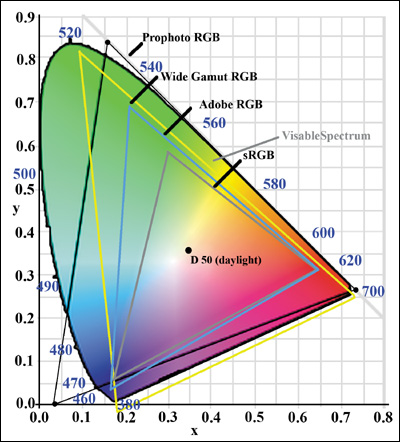

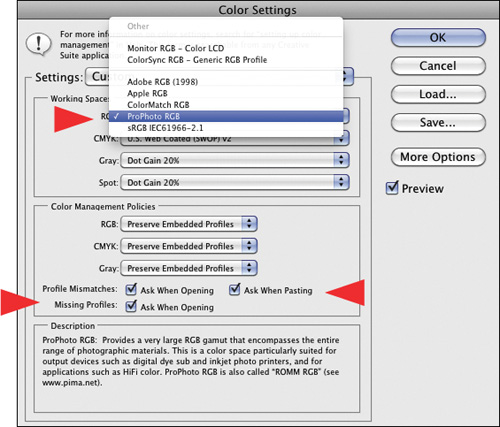

Before you begin working on Challen’s image, you need to have Photoshop set up for a non-destructive workflow. A non-destructive workflow is one in which you may do many manipulations without ever altering or losing the original file data. A typical non-destructive workflow starts when a RAW file is opened in the ProPhoto RGB color space in 16-bit. There is little or no clipping of colors in ProPhoto RGB (Figure 1.1.1), because it is such a large color space. It is the only color space that can contain all of the color that your DSLR can create. Files can always be converted later into smaller color spaces like sRGB (Figure 1.1.2) for display on the internet, but when a RAW file is opened in a smaller color space like Adobe RGB (Figure 1.1.3), colors that could have been printed had you used ProPhoto RGB are no longer in the file. Compare all of the color spaces in the visible spectrum in Figure 1.1.4.

Figure 1.1.1. ProPhoto color space

Figure 1.1.2. sRGB color space

Figure 1.1.3. Adobe RGB (1998) color space

Figure 1.1.4. The visible spectrum and the three color spaces

Note

Once you capture in or convert into a smaller color space, all you have are the colors of that space. So if you have been converting your sRGB captured files into ProPhoto RGB thinking that you maximized the gamut of color, what you really have done is similar to pouring a quart of water into a gallon container; it is still only a quart of water.

Staying in 16-bit vs. 8-bit preserves all the tonal transitions in the RAW capture. Every time you adjust a file in Photoshop, Lightroom, Capture NX, or whatever RAW processor you choose, some information is lost. Staying in 16-bit guards against excessive information loss that could lead to posterization and banding. In the past, many photographers shied away from working in 16-bit due to large files sizes that slowed their workflow and were expensive to store. With dramatic improvements in computer processing power, coupled with equally dramatic decreases in the cost of storage, this is no longer the hurdle it once was. Non-destructive workflow ensures that any image editing can be undone, files stay in ProPhoto RGB 16-bit, and are saved in lossless formats such as .psd, .psb or .tif. Most importantly, this allows for the future growth and improvement of both technology and an individual’s technique. The reason for this revision is that, not only have the technologies available today improved, my understanding of how to exploit Photoshop has grown.

Set Up a Non-Destructive Workflow and Create a Custom Workspace

Step 1: Photoshop Preferences

Photoshop CS5 ships with a series of preset workspaces, any of which allow you to achieve a non-destructive workflow. I am going to tell you how to fine tune one of them, and then I will have you save this as a custom workspace. The reason for this is one of exit strategy; something you always want to afford yourself whenever you edit an image. You do this so that if anything happens to your settings, your computer crashes, or your menus get moved or closed, all you have to do is click on your custom workspace and you will be back in business.

- When you open Photoshop after you first install it, it defaults to the Essentials workspace. Go to the Window pull-down menu, select Workspace and then Photography (Figure 1.2.1).

Figure 1.2.1.

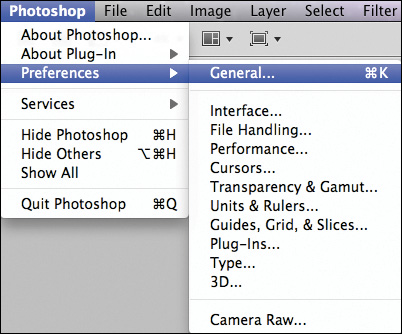

- Go to the Photoshop pull-down menu, select Preferences > General (Command + K for Mac / Control + K for Windows) (Figure 1.2.2) and the Photoshop Preferences dialog box will come up.

Figure 1.2.2.

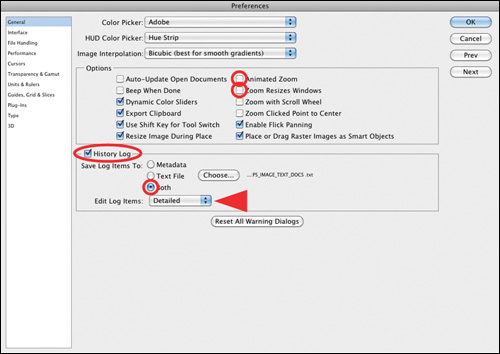

- In the General Settings box, leave the Color Picker set to Adobe, and Image Interpolation set to Bicubic. In the Options dialog box, turn off Animated Zoom.

- Next, click on the History Log and select Both. When the Save dialog box comes up, select New Folder and name that folder PS_IMAGE_TEXT_DOCS. Click Create and then Save in the Save dialog box (Figure 1.2.3).

Figure 1.2.3. Turning on the History Log

Note

I place the PS_IMAGE_TEXT_DOCS folder on the desktop. I also create a folder on the desktop bearing the name of the image on which I am working. Into this folder, I put a copy of the original RAW file, a copy of the modified RAW file, the layered .psd file, and any other files that I create related to that specific image. Make sure to name this folder so that it reflects the specific image to which all the files in it belong.

All of the choices I have had you make here are personal workflow choices. Although all of the features that I have had you turn off are well-executed pieces of code that are visually beautiful, I have disabled them because I find them visually distracting so they slow me down.

I find the History Log to be useful. (The older I get, the more useful I find it.) Its uses are twofold: you have a record of what you have done, which helps in figuring out the bill when you are doing work for someone else, and you have a written record of what you have done in case you want to replicate an effect. If you find you do not need the History Log, come back and turn it off—just be sure to save the changes in the custom workspace.

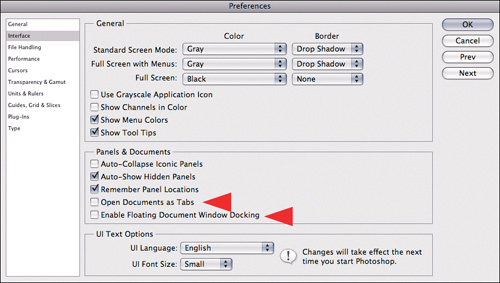

- Select Interface from the Preferences dialog box. In the General part of this dialog box, use the default settings. In the Panels & Documents part of the dialog box, however, turn off Open Documents as Tabs and Enable Floating Document Window Docking (both of these features make working with multiple images difficult and add unnecessary steps when you are engaging in an image harvesting workflow) (Figure 1.2.4).

Figure 1.2.4. Disabling the Open Documents as Tabs option

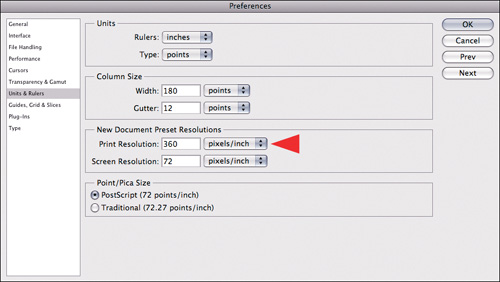

- Select Units & Rulers from the Preferences dialog box. Enter your unit preference (centimeters or inches) and, for new documents, I change the resolution to 360 ppi from 300ppi (Figure 1.2.5).

Figure 1.2.5. Setting the default resolution to 300ppi

Note

Because Epson printers, which I use, produce the best results at resolutions of either 240ppi or 360ppi, I select 360ppi. HP and Canon do best at 300ppi. This is because of the nature of the printer head technology. Epson uses Micro Piezo whereas HP and Canon use a thermal approach. The Epson head is far more accurate with regard to dot placement than either Canon or HP. I use primarily 360ppi because I do a lot of black and white images, and the majority of them are printed on Exhibition Fine Art paper, which is a glossy surface paper that holds dot structure better than any other paper I have used. I sometimes use a resolution of 240ppi when I am printing on fine art, cotton-based papers. This has to do with dot gain or the expansion of the ink dot due to the tooth of the paper.

- Click OK. You will now set up the next part of Photoshop for an Oz workflow.

Step 2: Setting Up Photoshop Color Space Preferences and File Bit Depth

- Go to Edit > Color Settings (Command + Shift + K / Control + Shift + K). The Color Settings dialog box will come up. Its default is North American General Purpose.

- Select North American Prepress 2. In the Working Spaces part of the dialog box, click on the RGB pull-down menu and select ProPhoto RGB (Figure 1.3.1). Click OK.

Figure 1.3.1.

Note

You should do this so that all of the color space warnings are turned on. It is important to remember that once you assign a color space, unless the needs of image editing require that you go from a larger color space to a smaller one, you should use the color space of the file as it is.

Another reason to turn on the color space warnings is so that you are aware of any possible shifts in color that will happen when working with multiple images. Being aware of a possible color shift is important in case you need to address it.

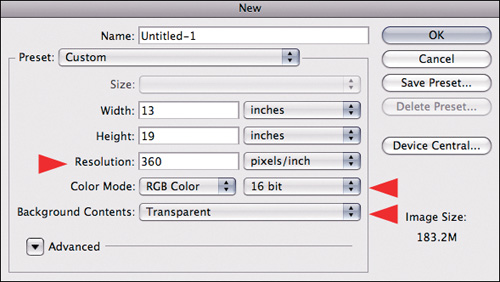

- Go to File > New File (Command + N / Control + N). Click on the Bit Depth pull-down menu and select 16 bit. For Background Contents, select Transparent (Figure 1.3.2), and leave the Width and Height at their default values. Click Save Preset, and then click OK in the New Document Preset dialog box. Click OK in the New File dialog box, and then click Command + W / Control + W to close the file that you just created.

Figure 1.3.2. Setting the New Document preset

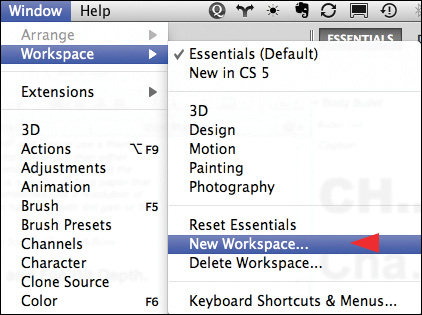

- Go to Window > Workspace > New Workspace... and save this workspace (Figure 1.3.3) in the New Workspace dialog box, naming it Workspace Oz2. Click Save.

Figure 1.3.3. Creating a New Workspace

Photoshop is now set up and optimized for photographic image editing.

Practicing at Practicing: Image Maps

If a cluttered desk is the sign of a cluttered mind, what is the significance of a clean desk?

—Dr. Laurence J. Peter

Step 1: Using Image Maps

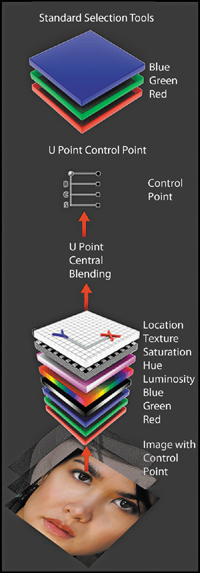

As an optical sensing device, the human eye scans a scene in a predictable sequence. It first goes to patterns it recognizes, then moves from areas of light to dark, high contrast to low contrast, high sharpness to low sharpness, in focus to blur (which is different than high to low sharpness), and high color saturation to low.

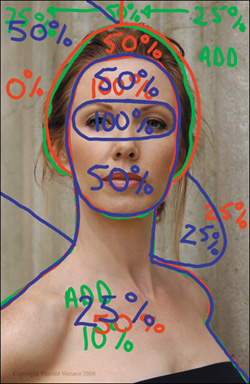

In order to make the viewer’s eye move across the image in a way that you decide it should, you must manipulate the light and dark areas, their contrast, their sharpness, their degree of focus or blur, and their saturation. So as not to feel overwhelmed when undertaking such a task, you should start by creating a list of the changes you would like to make. This is best done by creating an image map.

An image map is a Photoshop layer that sits on top of the image layer stack, on which you can make notes about what you are planning to do to an image. You can also use it to make notations on the various steps you will take, but what it does best is teach you how to create image-specific workflows. An image map is a planning device that helps you see the trees from the forest.

Note

You can download a tutorial QuickTime movie entitled “How to Make an Image Map” from www.welcome2oz.com (the same place you downloaded the source files for all of the lessons in this book). As I noted at the beginning of this chapter, image maps work best if you have a tablet or a pen-based display. Although it is possible to do everything in all the lessons in this book with a mouse, or even the trackpad of a laptop, you will be better served if you use a pen- or tablet-based system.

Keep in mind that image maps are designed to go away. They are the equivalent of training wheels. They are a good way to teach yourself how to organize and see, but you will not need them forever. To practice at practicing, you should do every lesson in this book with them and then again without them.

Another good reason to use image maps is that they allow you to make notes to yourself for retouching when you meet with a client. (I have the client sign the layer, so that there is a record in the file of what he wanted done and so there are no questions when I deliver the final image.) Image mapping also allows me to return to an image and note what I have done while it is still fresh in my mind so that I have accurate notes for the future.

Before you take the first “how to” step toward creating an image map, consider how believable you would like the finished image to appear. In this lesson, you do not want the viewer to know that you did any manipulation in Photoshop; you want to mimic what would have occurred had the model been properly lit in the first place.

A way to explain this can be found in Aristotle’s Poetics. In this work, he suggested that a believable improbability is better than an improbable believability. I believe this to be true and have extended this concept to define believable probability. What are these concepts and why are they important to digital photography?

The easiest way to understand these concepts is by using examples. Good examples of believable improbability are found in the Star Wars sagas. We do not travel faster than the speed of light, and walking, talking robots with feelings do not yet exist. In spite of this, we are willing to suspend disbelief, because the stories of love, longing, and conflict are believable even though they are improbable. In contrast, what follows is an example of improbable believability. I buy a lottery ticket in Los Angeles and the jackpot is $100,000. I win! The next day, I fly to New York City, buy another ticket, and win a jackpot of $75,000,000! The next day I fly to Chicago, repeat the process and win again! Although this could happen, you don’t believe it because it is so improbable.

The third concept, that of believable probability, can be explained using the Challen Cates image. You will create an image using Photoshop that the viewer will find both probable and believable, because the final image will be lit as though I had had the proper lighting equipment when I made the initial capture.

In order to assure that you create a believable probability rather than an improbable believability, you need to make sure that every choice you make in Photoshop leads to a result that will mimic the reality of proper lighting. For example, if you create a light that appears to shine from above, you need to create corresponding shadows that follow the direction of that light.

There will be images in which you will want to create a believable improbability. (There are some in this book. Try to identify them as you progress through the lessons.) The key to making something believable, no matter how improbable it may be, is to make sure that it conforms to the logic of our reality as much as possible. Once you have defined your goal for a particular image, you can begin to create image maps.

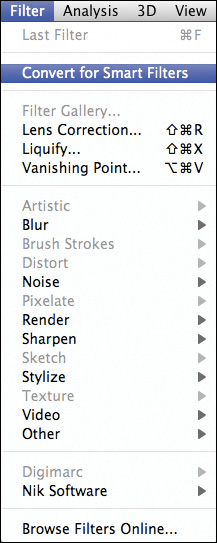

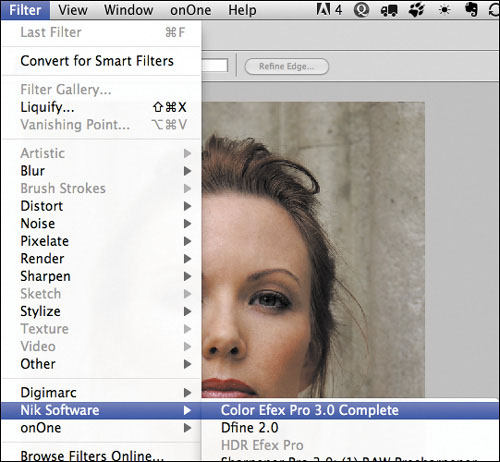

There are three free filter plug-ins from www.niksoftware.com/ozlessons: Tonal Contrast, Contrast Only, and Skylight filter. They will show up in your Filter pull-down menu under Nik Software as the Versace Edition. At the time of writing this book, the Nik Software filters only work in 32-bit in the Macintosh operating system; however, they work in 64-bit in Windows. Nik Software is in the process of updating them, but until then, Mac users will have to run CS5 in 32-bit. You do this by Control-clicking on the CS5 application icon. Select Get Info and click on the Open in 32-bit Mode checkbox. Close the window and start Photoshop.

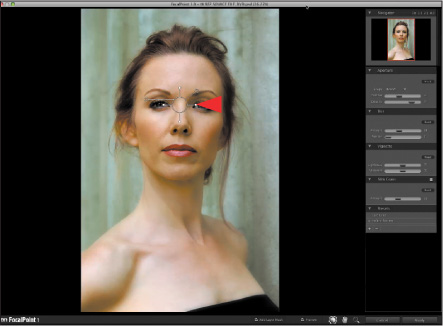

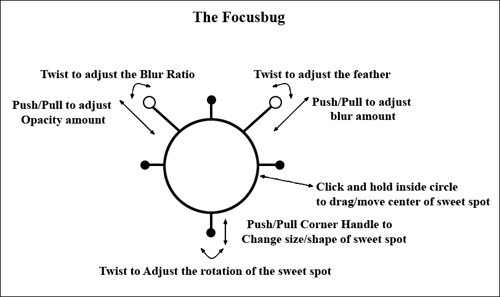

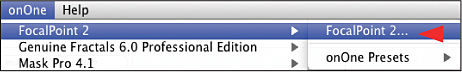

You will also need to download the free copy of onOne Software’s FocalPoint 2.0 from www.ononesoftware.com/ozlessons. This is a fully functional version of the software and you will be a fully licensed user.

Lastly, once you have installed everything, if you are not working in the ProPhoto RGB color space, you need to set Photoshop to ProPhoto RGB. You do this by going to Edit > Color Setting (Command + Shift + K / Control + Shift + K) so that the Color Settings dialog box comes up. Select North American Prepress 2 in the Working Spaces in the RGB pull-down menu and, also, change the setting from Adobe RGB 1998 to ProPhoto RGB. Click OK.

Creating an Image Map

- Open the image “SHIBUMI_SOURCE_16BIT.tif” (located in the CHAPTER_01 folder that you downloaded from www.welcome2oz.com) in Photoshop.

Note

There is also a video on youtube.com where you can watch how I make an image map. The URL is http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5ki3QhJkw-4.

Make sure that the image is in the neutral gray workspace by pressing the letter F. The gray space is best for making color decisions, because it gives you a color-neutral background. Gray is specifically used to minimize chromatic induction (visual color contamination), and a gray midtone is used to minimize contrast effects. By choosing a gray background, you can make the most informed decisions about changing the color, contrast, and shade of the image with which you are working.

- View the image in full screen (Command + 0 / Control + 0), and choose the Pencil tool from the tool bar (in the same place as the Brush tool). Double-click on the Set Foreground Color box in the Tools panel (the black and white squares located toward the bottom of the Tools panel). This brings up the Color Picker dialog box. Select a bright color. (I generally start with red and then work my way down on the color selector.)

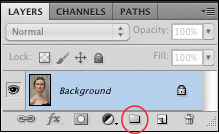

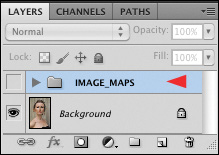

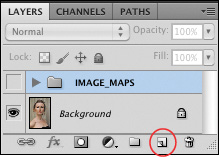

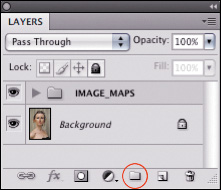

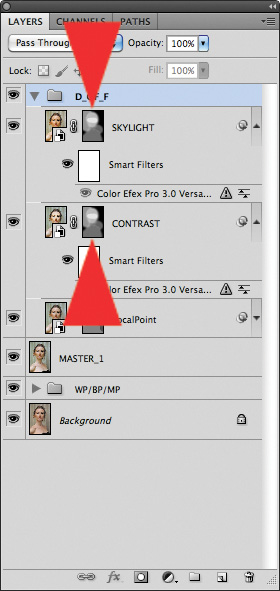

- Make sure the Layers panel is open, and click on the Create a New Layer Group icon (Figure 1.4.1). This will create a Layer Set folder in the Layers panel. Name the new layer set IMAGE_MAPS (Figure 1.4.2).

Figure 1.4.1. Create a New Layer Group icon

Figure 1.4.2. Creating the Layer set IMAGE_MAPS

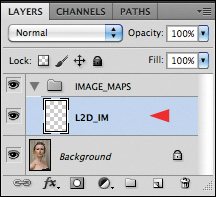

- Create a new layer by clicking on the Create a New Layer icon (Fig 1.4.3). Call the new layer L2D_IM (for Light-to-Dark image map) (Fig 1.4.4).

Figure 1.4.3. Create a New Layer icon

Figure 1.4.4. Renaming the layer L2D_IM

Note

At any level of expertise, giving your layers meaningful file names is an important part of creating an effective workflow. If many months after working on a file, you want to return to it to try a new technique, you will immediately grasp the purpose of each layer on which you originally worked and be able to retrieve the appropriate one on which to try your new approach. Perhaps you made a print or sent a file to a client, and changes are needed. Knowing at a glance what you did to the image will make life a lot easier should you have to go back and redo or undo something. It also makes your practicing at practicing sessions easier. If you get lost, you have an easily readable and retrievable road map.

- Select a brush size of 25 pixels. (You increase or diminish a brush’s size by pressing the square bracket keys, which are on the keyboard next to the letter P. Pressing the left bracket makes the brush smaller; pressing the right bracket makes it bigger.)

Note

Correct brush size is determined by the size and resolution of the image, so focus on the visual size of the brush, and not on its pixel size. For example, a 25-pixel brush would be much too large to use on a small, low-resolution image.

The Relationship of Light to Dark

For the first part of this lesson, I want you to manipulate the variables that I mentioned at the beginning of Step 1: light-to-dark, high-to-low contrast, and in-focus-to-blur. Remember, it is the person creating the image who decides the journey that the viewer’s eye will take. And it is that journey that causes the viewer to see the story you wanted to tell.

You control where the viewer’s eye will go by manipulating variables such as focus, light, and dark. I contend that when we view anything at all, there is both an unconscious and a conscious element involved. First, our unconscious eye, or the anatomical structure that makes up the eye, scans in the predictable manner I described above. Then, the conscious eye, the mind’s eye, interprets the image seen. It is how you control the unconscious eye that determines how the viewer interprets the image. This is a theme to which I will frequently return.

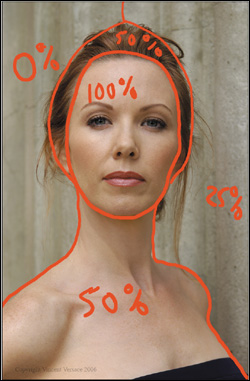

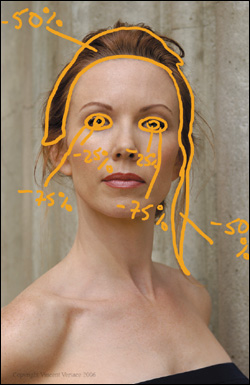

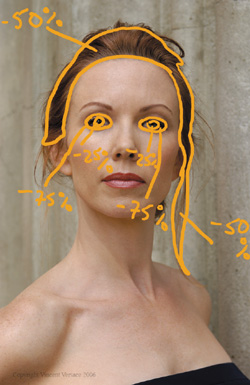

In general, I like to begin manipulating light-to-dark, thereby exploiting the unconscious eye’s tendency to move from light areas to dark ones. For this specific image, I want the viewer’s eye to go first to the face, then to the torso, then to the rest of the image.

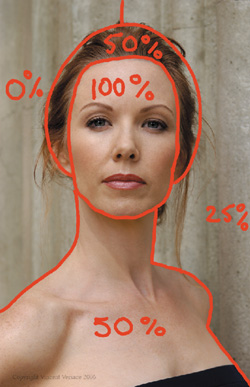

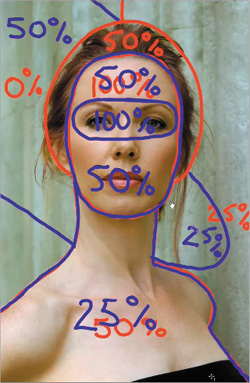

You must first decide what ratio or relationship of light-to-dark to create within this image. I wanted the face to be brightest, so I set it at 100%. As light’s circle of illumination increases, its intensity diminishes, so set the hair and torso at 50%. The background should be darker than the face, hair, and torso. The light on the background should go from light to dark as the eye moves from right to left. (I will explain why in a moment.) Set the right side at 25% and the left side at 0%.

Note

As you create your image map, keep in mind that these percentages are just notations. You can change them any time. You are working from the global to the granular.

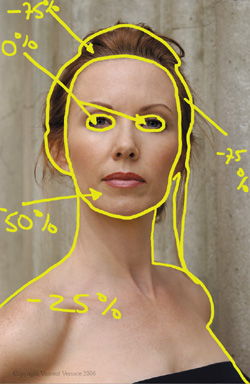

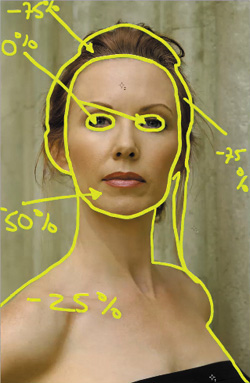

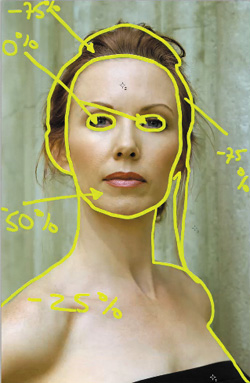

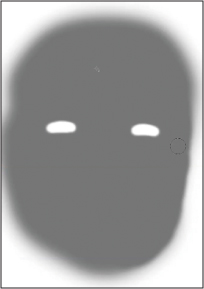

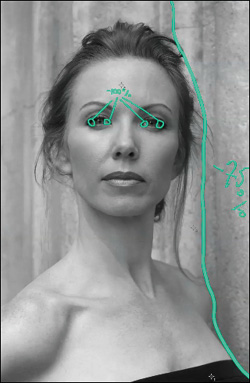

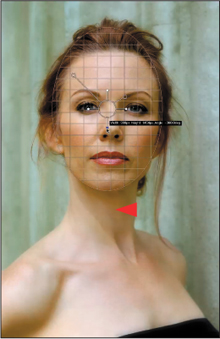

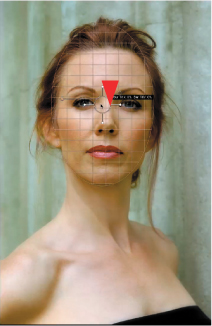

After those values are drawn on the L2D_IM layer, the image will look like this (Figure 1.5.1).

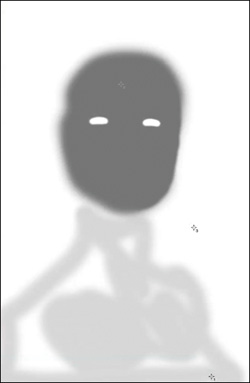

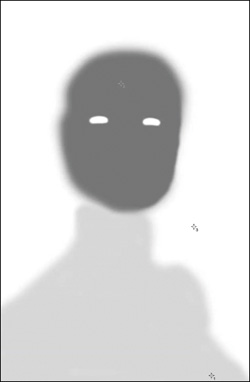

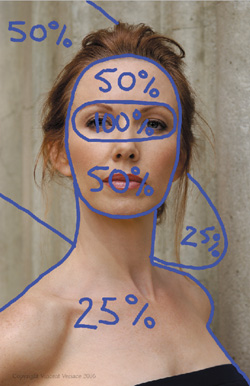

Figures 1.5.1 and 1.5.2. Light-to-dark image map, and Lighting image map

Placing Key and Fill Lights

If I had had all my lighting equipment at the photo shoot, I would have started by lighting the background, and I would have cross-lit it from left to right. Then I would have set key lights and fill lights. With a portrait, you usually want the viewer’s eye to go first to the subject’s eyes, so that is where you should put the key light. Then you might put fill lights on the lips and, to some degree, the torso.

Create a new layer and name it LIGHTING_IM (for Lighting image map). Pick a color other than red from the Tools panel to draw your lighting choices. (I chose blue.)

Here is the LIGHTING image map (Figure 1.5.2) showing the notation of the percentages I used: eyes: 100%, face: 50%, torso: 25%, and background areas: 50% and 25%.

The Illusion of Depth of Field

When shooting portraits, I find that a shallow depth of field (where only the subject is sharp and the background is out of focus) is visually pleasing. When you focus on the subject’s eye that is closest to the camera, the depth of field (the zone of acceptable sharpness) on the face will extend from the tip of the nose to a little past the ear. Generally that means shooting at f/5.6.

Create a new layer and name it D_OF_F (for Depth of Field), and pick a new color to use for your next set of image map notations (I chose light green) (Figure 1.5.3).

Figure 1.5.3. Depth of Field image map

In this case, the image was shot at f/6.3, with the model standing right against the wall, underneath the diffuser. The result is too much depth of field (DOF), with everything in focus, including the background.

Note

One of the issues that occurred during Challen’s photo shoot was that in order to evenly light her, I had to place her almost against the wall. I would have preferred that she be some distance away from and at an angle to it. In order to create this illusion in Photoshop, so as to achieve a believable probability, I had to create the correct quantity of in-focus-to-blur that would have occurred had I actually lit her properly and positioned her away from the wall. You also need to apply some degree of blur to her torso. (Since the point of focus is her eye, and one-third forward from that point should be in focus, the area in focus should stop at the tip of her nose. Any areas of her torso that extend past her nose should not be in focus.)

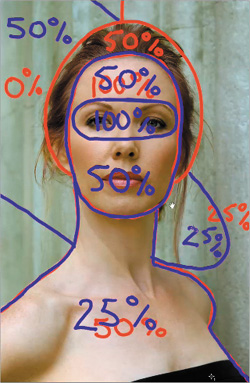

You now have a basic workflow to follow for manipulating the lighting and DOF of the Challen Cates image in Photoshop (Figure 1.5.4). (Keep in mind that the values I chose to use are only approximations and reflect relationships specific to this image.) Starting with a completely flat-lit photograph, you are now well on the way to creating a believable probability.

Figure 1.5.4. Combined image maps

Make the image maps invisible by clicking off the eyeball of the layer set IMAGE_MAPS. They will be out of the way, but available when needed.

Step 2: Correcting Digital Sensor Color Cast

Now that you have an image roadmap, working from the global to the granular, the next biggest issue is the correction of the image’s CCD/CMOS color cast. It is an important issue because it will affect all of the image editing choices you will make from this point on.

All RAW images, from any digital camera, exhibit some form of color cast as a result of the interpolation process that occurs when you bring that image into digital manipulation software such as Photoshop. The Challen Cates image on which you are working has a magenta/yellow haze.

The most effective way to remove this type of color cast is to first define the black and white points of the image. Finding the white point is a bit more problematic than finding the black point—and finding a gray point is even more elusive—but you are going to find all three by using a Threshold adjustment layer.

There are some rules that are important to know when removing color cast caused by the interpolation of the data from a CCD/CMOS sensor. When looking for the black point, select your sample point from an area of “meaningful” black rather than using the first black pixel you see. If you select the very first black pixel that you see, it generally has RGB values that are R:0, G:0, and B:0. If no information was recorded, no color contamination exists. What you are looking for is a black pixel that has RGB information in it.

Finding a white point is completely different. You do not want to select a white point from an area of “meaningful” white. Rather, you want to find the pixels that are closest to pure white, without actually being pure white. (A pure white pixel will have RGB values of R:255, G:255, and B:255, which is of the same usefulness as a black pixel that has RGB values that are zero.) What makes finding a white point so problematic is that, much of the time, visible white and measurable white are two different things. (Measurable white, using the Threshold adjustment layer method, will always be biased to R:30%, G:60%, and B:10%, while visible white generally consists of equal values of RGB and tends to be a lot bluer than measurable white.) In addition, there are instances when there is no white point at all and, occasionally, there may be aspects of the white point color cast correction you may not like, i.e. you may actually like aspects of the color cast. For these reasons, it is a good idea to separate the black and white points into separate Curves adjustment layers, because it gives you options that you will see as this lesson progresses.

Note

Looking at this image, visible white is found in the catch light of the subject’s eye.

Conceptually, it may be more accurate to view setting a white and black point as setting a light and dark one, because you do not want to use the pure white (R:255, G:255, and B:255) and pure black of an image (R:0, G:0, and B:0); you want to be as close as possible to those values without reaching them.

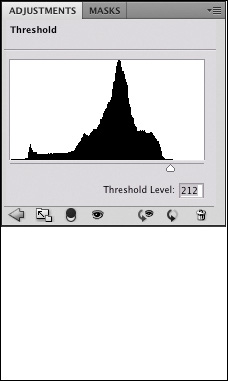

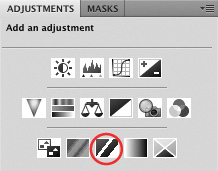

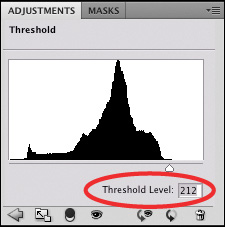

How to Find Black and White Points Using a Threshold Adjustment Layer

1. Make the background layer active. If you are working in CS4 or above, go to the Adjustments panel and select Threshold by clicking on the Threshold adjustment layer icon (Figure 1.6.1). (If you are working in CS3 or below, go to the bottom of the Layers panel, click on the Create a Fill or Adjustment Layer icon, and select Threshold.) A black-and-white representation of the image appears (Figure 1.6.2).

Figure 1.6.1. Threshold adjustment icon

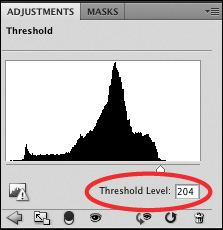

Figures 1.6.2 and 1.6.3. Black and white image with Threshold adjustment applied, and whole image with first meaningful black

2. If you are working in CS4 or above, make sure that the Eyedropper tool is selected. (If you are working in CS3 or below, the tool is automatically selected.) Move the triangle slider (located at the bottom of the Threshold dialog box) to the left until the image goes completely white. As you move the slider slowly back toward the right, you will see image detail start to emerge in black. The first meaningful area of black that you see is where you should take your black sample point (Figures 1.6.3). (Meaningful black is an area in which you can see “something.”)

3. Choose a black point from the top of the model’s dress by zooming into this area (Command + Space / Control + Space gives you the Zoom tool) and then by Shift-clicking a sample point (Figures 1.6.4).

Figure 1.6.4.

4. Bring the image back to full screen (Command + 0 / Control + 0), and move the triangle slider all the way to the right. The image will be completely black, but you should see a sample point (your black point) bearing the number 1 in the lower right corner.

Note

Even though you see “meaningful” black in areas of the model’s hair and eyes, I chose to put my black point in the model’s dress, because her dress was actually black. You will notice, however, that the dress’s color recorded as dark blue.

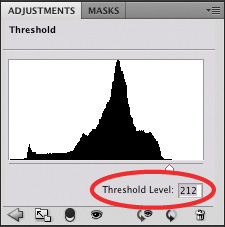

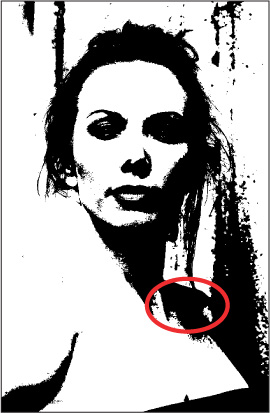

5. Move the slider slowly back to the left until the first area of white pixels appear. (I saw this at a Threshold level of 212.) (Figures 1.6.5)

Figure 1.6.5.

Note

When choosing a potential white point, get as close as you can to the first white pixel that you see. If that pixel has an RGB value of R:255, G:255, and B:255, just like the a black point that has a RGB value of 0,0,0, it contains nothing to measure. This is why you should get as close as you can to the first white pixel without actually selecting it. To remove a color cast, you must have a pixel that has a variation between the red, green, and blue pixel values.

6. The three areas that come up are on Challen’s shoulder, cheek, and forehead. Move the slider to the right so that it is at the very end of the black in the histogram shown in the Threshold dialog box. (For this image, that is a threshold level of 204.) What you should now see is one white square in a field of black (Figures 1.6.6 and 1.6.7).

Figure 1.6.6.

Figures 1.6.7 and 1.6.8. Three areas of white in Threshold preview, Sample point 2 placed on the white pixels

7. Zoom into the area of the white squares above her shoulder. One of these three white squares is going to become your white point. You are going to further define your white point by moving the threshold level upward. Click on the white triangle and slowly move it until only one white square remains, which occurs in this image at a threshold level of 207. Make sure the Eyedropper is selected in the tool bar. Shift-click on the white square, and you should see a sample point appear with the number 2 (Figure 1.6.8).

Finding a “Sometimes” Midpoint Using a Threshold Adjustment Layer

Contained within every image is a set of numbers (RGB values) that corresponds with the always-difficult-to-find midpoint value. What follows is the easier of the two ways to find that midpoint; the one that works when the image has easy-to-find neutrals. (Later in this book, you will learn how to find a midpoint value even when you cannot see one.) The concrete wall behind Challen is made up of neutral tones that lend themselves to finding a useful midpoint.

8. Bring the image back to full screen (Command + 0 / Control + 0), and move the triangle slider until the Threshold Level is at 128 (Figures 1.6.9 and 1.6.10). When you turn the Preview Eyeball off on the Threshold adjustment layer located at the bottom of the dialog box, you will see a red line through the Eyeballs. (In Photoshop CS3 and below, click off Preview.)

Figure 1.6.9. The image at a Threshold of 128

Figure 1.6.10. The Threshold adjustment set to 128

9. Zoom into the model’s right shoulder containing the desired neutral values (Figure 1.6.11).

Figure 1.6.11. Zoom into the shoulder

10. Click on the Preview Eyeball of the Threshold adjustment layer. In the Threshold, type 127, and press Return. Command + Z / Control + Z back and forth, and observe where black pixels appear and reappear on the wall. Once you have found an area like this, zoom into it. Repeat toggling back and forth between a threshold level of 127 and 128, and watch where the pixels appear and reappear. When you return to a threshold level of 128, pick a single pixel that reappears, and place your third sample point (Figure 1.6.12).

Figure 1.6.12. The third sample point

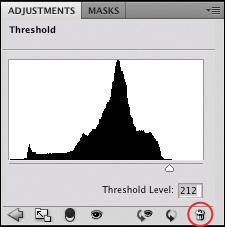

11. Click the Trash Can icon (Figure 1.6.13) to discard the Threshold adjustment layer (or select Cancel in the Threshold dialog box if you are working with CS3 or below). This layer was needed only to help you locate the potential white, mid- and black points.

Figure 1.6.13. Discarding the adjustment

Living in the Land of 2%

Whenever you work on an image, regardless of the RAW processor you use, you clip data that results in the introduction of artifacts. It is extremely important to understand that such artifacting is cumulative and can become multiplicative. Furthermore, the image data that you see when you first open a RAW file (before you do anything to it) is the cleanest it will ever be.

When you decide to manipulate your file, you must decide whether or not to live in the land of 2%. If editing an image brings it 2% closer to your original vision, you must do it, and thus, you are living in the land of 2%. To paraphrase Viola Spolin (internationally renowned theater educator, director, and actress), the moment you decide something in the creation of your work doesn’t matter, is the moment you decide that your work doesn’t matter. I believe that everything you do must matter. What becomes your greatest challenge is editing your image so as to remove only those things that are not compatible with your original vision in such a way that you create the smallest amount of artifact possible.

Why and how I do many of the things I do is because I want my image to be 2% closer to my original vision, but I do not want to cause a possible 15–20% quality decrease in my image file due to the cumulative and potentially multiplicative aspects of artifacting. Everything I do is in service of the print, which is in service of my vision, or voice, and I want my voice heard and my vision seen without any detractions.

That brings me to another thought. I have been talking about correcting a digital file’s color cast, but not all color cast is objectionable, and sometimes, it may merely be aspects of the color cast you do not like.

This is what I know:

- All images have a color cast.

- The color cast may be objectionable, or merely aspects of the color cast are objectionable.

- Aspects of color cast may be usable.

- The untouched file is the cleanest it will ever be.

- Anything I do to this file clips data and introduces artifacts.

- All artifacting is cumulative and may be multiplicative.

- When working on a image, I want to clip as little data as possible.

- I want the greatest image control I can get.

- I always want to be able to undo what I have done.

I want you to apply these thoughts to the task at hand, which is removing the color cast of this image, while sparing the loss of information and maintaining the greatest amount of aesthetic control possible. You will do this is by using separate Curves adjustment layers for setting this image’s white point, black point, and midpoint. Because you will make one adjustment per layer, you will minimize the artifacts that you will introduce.

Since I adhere to Albert Einstein’s tenet that we should make things as simple as possible and no simpler, why would I want you to use three separate Curves adjustment layers when it would be simpler to do the three points on just one? The reason is that the resultant images are profoundly different. This is what the image looks like when I separate out the black, mid-, and white points onto three separate Curves adjustment layers (Figure 1.7.1), and this is what it looks like when I do the three points in just one (Figure 1.7.2).

Figures 1.7.1 and 1.7.2. Comparing the effect of three separate curves adjustments (left) with one (right)

Another reason to use three separate curves is that if you combine the three points into one Curves adjustment layer, you lose control over your image. You cannot return to the image (should you decide or need to) to brush things backward, change opacities, or re-blend the colors. Some photographers use one layer to save space on their hard drive and to simplify their workflow. The result, however, is that they are stuck with what they have done. Trying to make something simpler than it should be can cause many unanticipated problems.

Another benefit of this approach is that you can control the amount of whatever effect you are using: globally through the use of the layer’s opacity (in the Layers panel), and selectively through the use of layer masks for each of the adjustment layers.

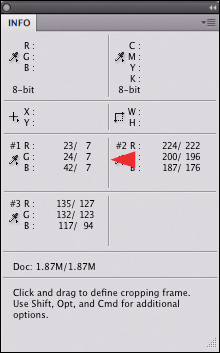

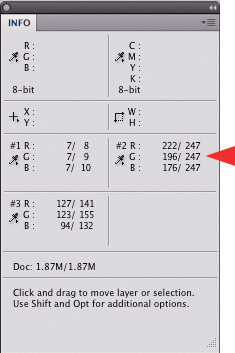

Using Multiple Curves Adjustment Layers to Remove Color Cast

In Step 11, under finding a midpoint, you discarded the Threshold adjustment layer. After doing that, the image reappeared in color displaying the three sample points you created: one on the model’s cheek, one on the concrete wall, and one on her dress. The series of numbers that appear in the Info panel are the actual color values of each of those points. (Sample point 1—your black point: R:18, G:31, and B:17; Sample point 2—your white point: R:219, G:192, and B:208; and Sample Point 3—your midpoint: R:131, G:129, and B:114.)

Note

In CS3 and below, click Cancel to get rid of the Threshold adjustment layer. In CS4 and above, click on the trash can. Be aware, however, that in CS4 and above, if you are using actions or Extension panels, you click Cancel the same way you would if you were using CS3 and below.

If your numbers do not exactly match mine, it simply means that we picked slightly different sample points. Notice that the area you clicked on for your white point was not located in the area of the eye. In this instance, visible white is different from measurable white. For the purpose of demonstration, I placed a white sample point (and named it Sample Point 4) in the specular highlight of the eye. This is the whitest, visible white point in the image.

- Make sure the Layers panel is open, and click on the Create a New Layer Group icon (Figure 1.8.1). This will create a Layer Set folder in the Layers panel. Name the new layer set BP/WP/MP.

Figure 1.8.1. Create a New Layer Group icon

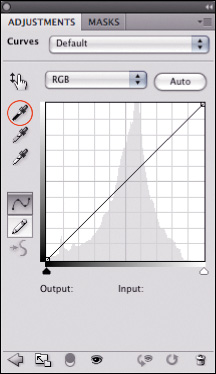

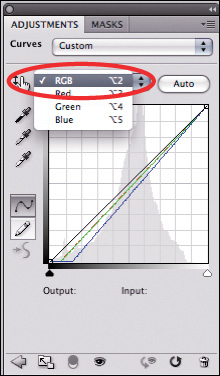

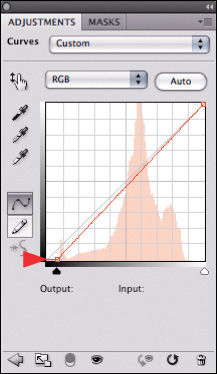

- Making sure that you are in the BP/WP/MP layer set and turn Caps Lock on; the pointer becomes the crosshairs cursor. If you are in CS3 or below, go to the bottom of the Layers panel, and click on the Create New Fill or Adjustment Layer radial button. (It is the third radial button from the left and is a half-white, half-black circle). Select Curves from the fly-out menu. You will now create the first of three Curves adjustment layers. If you are in CS4 or above, you can either create a Curves adjustment layer this way or you can use the Adjustment panel.

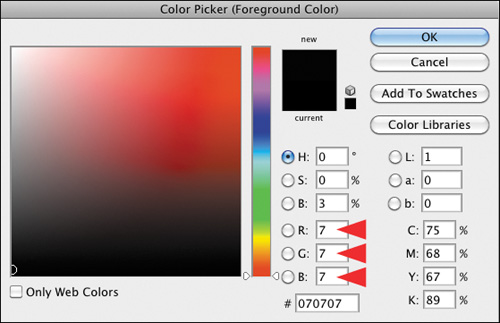

- When the Curves dialog box comes up, click the black eyedropper to set the threshold at which you want the black eyedropper to sample (Figure 1.8.2). Now, double-click on the black eyedropper that is located in the lower right corner of the dialog box. The Color Picker dialog box will come up. In the RGB values part of the dialog box, type 7 in the R, 7 in the G, and 7 in the B. Click OK (Figure 1.8.3).

Figure 1.8.2. The black eyedropper in the Curves adjustment

Figure 1.8.3. Setting new values for the black eyedropper

- Zoom into the area of sample point 1. Select the black eyedropper, which is the leftmost eyedropper of the three in the Curves adjustment layer dialog box, and you will see a circle with two crosshairs. Line the crosshairs up until it appears that there is only one, and click. Notice how the color changes (Figures 1.8.4 and 1.8.5).

Figures 1.8.4 and 1.8.5. Before the BP Curves adjustment and after the BP Curves adjustment

Note

The RGB values of R:7, G:7, B:7 approximate the beginning of what is known as Zone II (textured black) in the Zone system, as developed by Ansel Adams and Minor White. For further discussion of the Zone System, see The Zone System Manual by Minor White.

When you define the white point, you will set the white point eyedropper for the upper end of Zone IX (textured white), because in a fine art print, you are looking for 100% ink coverage in the highlights (no place where the paper shows through the ink) and shadows that have detail throughout. In other words, you want no paper showing and no ink wasted.

If Photoshop asks, “Want to save the new target colors as default?” click Yes for both the black and white point curves.

Because you are addressing issues of color (color cast), you are going to leave the blend mode of this Curves adjustment layer, as well as the one you are about to create, as Normal.

You will now see that, in the Info panel, sample point 1 has changed from values of R:19, G:17, and B:31 to values of R:9, G:9, and B:9. Your next task is to fine tune each of the RGB channels in your Curves adjustment layer to R:7, G:7, and B:7 (Figure 1.8.6). In so doing, you will recover some more data that may be potentially clipped in the course of removing color cast, as well as to remove the color cast from the black aspect of your image.

Figure 1.8.6. Equal RGB values for the black point

- From the Modify Individual Channels pull-down menu, select the Red channel and click on the anchor point at the bottom of the channel (Figures 1.8.7 and 1.8.8). Using the directional arrows on your keyboard (for this image, it is the right arrow), move the anchor point to the right until the number in the Info panel moves from 9 to 7. (For me, it was 2 clicks for all three channels.) Repeat this process for the green and blue channels. In the Info panel, all the RGB values should now equal 7. By redefining the black point, you have also removed the CCD/CMOS color cast from the black parts of the image (Figures 1.8.9 and 1.8.10). In the Layers panel, name this layer BP (for Black Point) and turn its eyeball off. You should repeat this process for the white and midpoints.

Figure 1.8.7. Selecting the Red channel

Figure 1.8.8. Fine tuning the anchor point

Figures 1.8.9 and 1.8.10. Before the BP Curves adjustment and after fine tuning the BP Curves adjustment

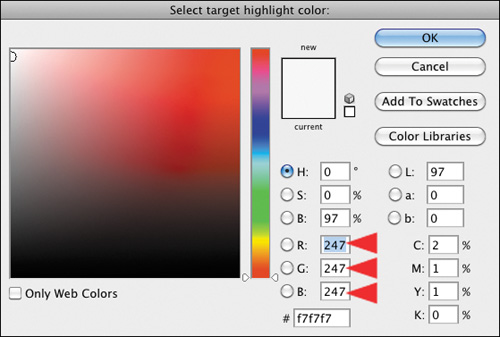

- Repeat the steps for creating a Curves adjustment layer. To set the threshold of the white eyedropper, select the white eyedropper, double-click on the white eyedropper and set the RGB values to R:247, G:247, and B:247. (This approximates the upper end of Zone IX) (Figure 1.8.11). Click OK. Zoom into the area of sample point 2, align the crosshairs, click, and then click OK. You have set the white point. In the Info panel, sample point 2 (the white point) should have changed from R:219, G:208, and B:192 to R:247, G:247, and B:247.

Figure 1.8.11. Setting the new white point values

- From the Modify Individual Channels pull-down menu, select the Red channel, and click on the anchor point at the top of the channel. Using the directional arrows on your keyboard (the right arrow for this image), move the anchor point to the right until the number in the Info panel moves from 253 to 247. (For me, it was 5 clicks to the right.) Repeat this process for the green and blue channels. (For me, the green channel was 5 clicks to the right, and the blue was 7 clicks to the left.) The RGB values in the Info panel should now equal 247 (Figure 1.8.12). In the Layers panel, name this layer WP (for White Point) and turn its eyeball off. Compare before (Figure 1.8.13) and after (Figure 1.8.14).

Figure 1.8.12.

Figure 1.8.13. Before the WP adjustment

Figure 1.8.14. After the WP adjustment

- For the last time, repeat the steps for creating a Curves adjustment layer. Select the Set Graypoint eyedropper. (Do not worry about double-clicking on the gray-point eyedropper; the RGB values are already set to R:128, G:128, and B:128.) Zoom into the area of sample point 3, align the crosshairs, click, and then click OK. You have set the midpoint or gray point. The Info panel for sample point 3 should have changed from R:131, G:129, and B:114 to R:124, G:124, and B:124.

- Once again, from the Modify Individual Channels pull-down menu, select the Red channel and click on the anchor point in the middle of the channel. Using the directional arrows on your keyboard (the left arrow for this image), move the anchor point to the left until the number in the Info panel moves from 124 to 128. (For me, it was 4 clicks to the left.) Repeat this process for the green and blue channels. (For me, the green and blue channels were both 4 clicks to the left.) The RGB values in the Info panel should now equal 128. In the Layers panel, name this layer MP (for Midpoint). Compare before the MP adjustment (Figure 1.8.15) and after (Figure 1.8.16).

Figures 1.8.15 and 1.8.16. Before and after the MP adjustment

- Now that you have dialed in each of the three correction curves, turn on the eyes of the BP and MP Curves adjustment layers. With all the layers on, the image should look like this: before and after (Figures 1.8.17 and 1.8.18).

Figures 1.8.17 and 1.8.18. Before and after the CCD/CMOS color correction

You have successfully removed the CCD/CMOS color cast from the white, mid, and black aspects of the image, thereby eliminating the color contamination inherent in the process of converting RAW files to any usable file format.

Making Lemonade from Lemons: Selectively Using File Color Cast to Your Advantage

When you create images that reflect your vision of the world, the only rule is that there are no rules. No one cares what you did to the image to make it look the way it does; they care only that your image moves them. The viewer wants so much to believe in your image that he or she is willing to suspend all disbelief to take the journey. What viewers do not want to see are the chalk marks of your post-processing, for if those are evident, their willing suspension of disbelief ceases. So when your image has some lemons, make lemonade; just do it so that no one can see the peels.

When trying to create a believable probability, you need to pay attention to the way people naturally perceive things. For example, painters are taught that warm colors appear to move forward in an image while cool colors move backwards. What is true for them is also true for photographers, which means that the closer an object is to the camera, the more warm, or yellow and red, it will appear. If the object is further away, it will appear cool or blue. Also, shadows tend to be bluer or cooler than areas that are lit, which tend to be warm. What this means is that if you are trying to create the illusion of DOF in the Challen image, in addition to making her look like she was lit with appropriate lights, you need to pay attention to the colors of things. (That attention needs to be paid from the very moment you open the file and choose to change something, because everything you do must be about minimizing artifact. You must also endeavor to create a workflow that makes things as simple as possible, but no simpler.)

One of the reasons that I wanted you to separate the black, white, and midpoint color cast corrections is so that you can have complete control over the colors of all objects in any of your images. You may decide that you want to use all three color cast corrections, but you may want to use just one or two, or none at all. You may also want to change the order of your three correction curves, as well as the individual opacities of each layer. Lastly, you may choose to selectively adjust the color of one or more of the smallest of areas by using layer masks. So even though all files you capture have varying levels of color cast, you will be able to use any part of that cast to your advantage.

Looking Before You Leap

Before you move on and do any brushwork, assess each of your color cast correction layers for what you do and do not like about each. At each point along the way to creating an image, you should re-evaluate what you have already done.

My first observation when I re-evaluate this image is that I do not like the overall color cast before correction. I do not, however, like the coolness of the image once the color cast is removed. I do like some of the warmth of the black point correction, but I do not like what it does to Challen’s eyes and hair. I like the overall effect of the white point correction, but not what it does to her face and hair. I like aspects of the original, uncorrected image, specifically the tones of her hair, and I am happy with the midpoint correction. With all these observations in mind, here are the first image maps that I drew: black point correction brush back (Figure 1.9.1) and white point correction brush back (Figure 1.9.2).

Figures 1.9.1 and 1.9.2. Black point correction brush back image map and white point correction brush back image map

Fine Tuning the Color Cast on the Curves Adjustment Layers to Set the Stage for the Creation of the Illusion of Depth of Field

With the global color correction behind you, the granular color correction is next. Begin by thinking through what steps you want to take.

I chose to begin on the BP and to brush back the model’s eyes in this layer, because there are aspects here that I like. Look at this before the black point correction (Figure 1.9.3) and after (Figure 1.9.4).

Figures 1.9.3 and 1.9.4. Before and after the BP adjustment

Then, look at the image before the white point correction (Figure 1.9.3) and after (Figure 1.9.5), and you can see that this correction cools the image and removes some of the color cast from her hair.

Figures 1.9.3 and 1.9.5. Before and after WP adjustment

If you look at the image before the midpoint correction (Figure 1.9.3), and then after (Figure 1.9.6), the image is even cooler than it was before you did the midpoint correction. When you put all three together, you get what the image looked like when I shot it, but it is not yet what I want it to become. Look at the image before the correction (Figure 1.9.3) and after the black, white and midpoint corrections (Figure 1.9.7).

Figures 1.9.3 and 1.9.6. Before and after MP adjustment

Figure 1.9.3. Before any corrections

Figure 1.9.7. After all corrections

In order to make this image match my initial vision of it, I must create the illusion of DOF. In order to do this, you will use color to your advantage. Since you now know that warm colors appear to move forward in an image, and cool colors appear to recede, if you make Challen’s face the warmest part of the image, her body the second warmest, and the background the coolest, you will begin to create the illusion that there is a greater separation of Challen from the background than there really was.

There are many things that you could do to this image to affect its color cast. You could individually look at the black, the white, or the midpoint; you could put them together as seen in Figure 1.9.7, or you could lower the opacity of each of the layers. But what I would like you to do, after looking at this Black point brush back image map (Figure 1.9.1), is to brush back the areas that I have drawn in and keep the areas with no notations: that means brushing back the pupils of her eyes, brushing back the whites of her eyes, and then her hair.

Finding the Gray Areas: Step 1: Fine Tuning the Black Point Curves Adjustment Layer

- Turn off the Black Point image map, and zoom into Challen’s face and hair. Make the layer mask active on the Black Point (BP) Curves adjustment layer.

- Select the Brush tool (keyboard shortcut B), and zoom in to her face. Set the opacity to 50% by pressing 5.

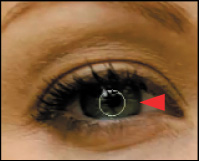

- Start with her eyes. Select the Brush tool (making sure that Caps Lock is off) and shrink it until it is just a bit smaller than her eye (Figure 1.10.1).

Figures 1.10.1. Setting the brush size

- Make sure that the foreground color is black. (Use the keyboard shortcut D to reset the foreground and background color. To reverse the foreground and background color, use the keyboard shortcut X.) You will paint with black, because the layer mask is white. Black conceals, white reveals. (See the sidebar Unmasking Layer Masks and the 80/20 Rule.) Start by brushing just the pupil of her eye.

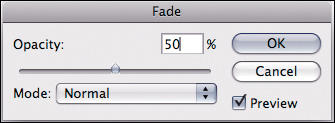

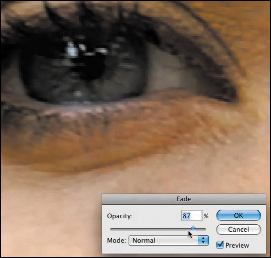

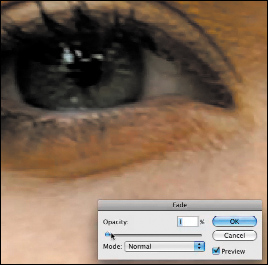

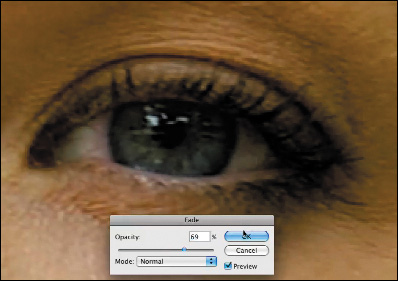

- Bring up the Fade effect tool by using keyboard Command + Shift + F / Control + Shift + F (Figure 1.10.2) or go to the Edit menu. Look at the effect at more than 50% (Figure 1.10.3) and at less than 50% (Figure 1.10.4). I selected 69% (Figure 1.10.5) because I liked concealing more of the correction. Click OK.

Figures 1.10.2. Fade effect dialog box

Figures 1.10.3. Fade set to more than 50%

Figures 1.10.4. Fade set to less than 50%

Figures 1.10.5. Fade set to 69%

- Hold the space bar down to bring up the Move tool and move the image over to her right eye (Figure 1.10.6). Brush over her right pupil as you did on her left eye. Next, bring up the Fade effect tool (Command + Shift + F / Control+ Shift + F). Type in 69% and click OK. You know it is going to be 69%, because it was 69% on her left eye and they should match (Figure 1.10.7).

Figure 1.10.6. Move to her right eye

Figure 1.10.7. Fade the brushwork to 69%

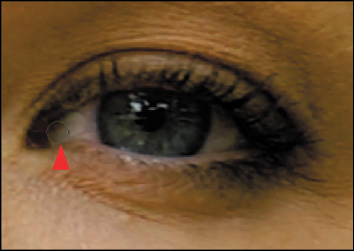

- Shrink the brush size by using the bracket keys located next to the letter P. The left bracket key makes the brush smaller, while the right bracket key makes it larger. The brush should fit in the area where her tear duct and her eyelid meet (about 20 pixels) (Figure 1.10.8).

Figure 1.10.8. Shrinking the brush size again

- Brush in the whites of her eyes at 50%.

Note

Although there is an unwanted overlap in the layer mask from inadvertently brushing over the same area, this is easily corrected. (See the sidebar Error-Free Layer Masks.)

- Once you have fixed the layer mask using one of the techniques discussed in the Error-Free Layer Masks sidebar (Approach 1 is the best choice for this image), use keyboard command D to reset the foreground and background colors to black and white. Next, select a brush opacity of 50%. (Keyboard shortcut 5 gives you an opacity of 50%.)

- Zoom out so that Challen’s face fills the screen. Using the right bracket key, increase the brush size to 90 pixels and brush back all of Challen’s hair. After that, bring up the Fade effect dialog box (Command + Shift + F / Control + Shift + F), and set it to 81% using the slider. Compare the before (Figure 1.10.9), and after (Figure 1.10.10), and look at the image map (Figure 1.10.11) and the final layer mask (Figure 1.10.12).

Figure 1.10.9. Before the brushback

Figure 1.10.10. After the brushback

Figure 1.10.11. The brushback image map

Figure 1.10.12. The resulting layer mask

Note

You do not have to be precise with the layer mask, because you can later return to and refine it using one of the approaches discussed in the Error-Free Layer Masks sidebar. Also, located at www.welcome2oz.com, there is a QuickTime presentation that you can watch on how to do this. Simply go to the source files for this lesson.

- Once you have brushed Challen’s hair back, Option- / Alt-click on the layer mask to display it. With the Brush tool still selected, set its opacity to 100% (keyboard shortcut 0). Then, Option- / Alt-click on the gray part of the mask. (Option- / Alt-clicking on a layer mask brings up the sample eyedropper.)

A Faster Layer and a More Accurate, Error-Free, Masking Workflow

Before you go further, I want to tell you how you can avoid some of the problems that can arise when you re-brush. In my opinion, the only way to find the right amount of gray for which you are looking is through the use of opacity. However, depending on whether the layer mask on which you are working is filled with black (for concealing the effect) or with white (for revealing the effect), using opacity may be problematic when you are trying to refine a layer mask created by using varying opacities of white and black. (See the 80/20 Rule sidebar.) The reason is that if I brushed on my layer mask at 50% and missed a spot that I later touched up and that overlaps my original brushing, that overlap would now be at 75%. (Fifty percent of fifty percent is twenty-five percent.) Just because my color may appear to be 50% gray, it is really still black. At 50% opacity, however, it will produce a 50% gray. So if I re-brush over anything on which I have already worked, it will be as if I was brushing at 75%. The outcome is the creation of a halo that is both undesirable and visible in the final image. If, however, I go to 100% opacity, and sample and paint with the grays that I created, I get to have my creative cake and eat it too. I no longer have to worry about creating halos, because all I am doing is painting with the same color gray that surrounds the area I originally missed. When you tightened up the eye aspect of this layer mask, you got a little taste of how useful this technique can be.

- Click on 0 (zero) to set the brush opacity to 100% opacity. Option- / Alt-click on the gray part of the layer mask. (Holding down the Option / Alt on a layer mask brings up the sample eyedropper. Clicking on it while holding down the Option / Alt key samples the color.) In the Tools panel, the color gray will show up in the foreground box. Brush in the white area and touch it up. The beauty of this approach is that it does not matter how many times you paint over the same area, because it is the same density of gray as the area that you sampled.

- Another advantage of working this way, is that once you have established the amount of density you want for Challen’s hair, you can keep painting with the same color, and you will get the same density of gray in your layer mask in those areas in which you have not yet done brushwork. Brush in the rest of the area that you mapped in your image map. Look at the layer mask and the image after refining the layer mask (Figures 1.10.13 and 1.10.14).

Figure 1.10.13. Refined layer mask

Figure 1.10.14. The image after refining the layer mask

You have completed fine tuning the Black Point Curves adjustment layer. Next, you will turn your attention to fine tuning the White Point Curves adjustment layer.

Step 2: Fine Tuning the White Point Curves Adjustment Layer

It is time to address the remaining granular adjustments of the white point. Before you begin, look at the White Point Brush Back image map before the adjustment (Figure 1.12.1), as well as the image map after the white point correction (Figure 1.12.2). Also, review the image before and after without the image map (Figures 1.12.3 and 1.12.4).

Figure 1.12.1. WP Brush Back image map before the correction

Figure 1.12.2. The same image map after the WP correction

Figure 1.12.3. Before the WP correction

Figures 1.12.4. After the WP correction

When the white point correction is applied, the image cools down. In Challen’s image, you are trying to create the illusion of DOF, as well as create the illusion that the image was actually lit with hot lights. While doing this, you must ensure that you stay as close as you can to the original file. With this in mind, look at the original image map.

I suggest leaving her eyes alone, but brushing about 75% of the white point correction back into her hair, 25% into her body, and 50% into her face. This allows more of the image’s warmth to bleed through. (Warm colors appear to move forward in an image and cool colors recede, so the background in this image appears to be further away than it actually was.)

- Make sure that the White Point Layer Mask is the active layer. Select the Brush tool (keyboard shortcut B) and make sure that the foreground color is black and the background color is white (keyboard shortcut D). Set the brush opacity to 50% (keyboard shortcut 5) and make your brush is about the size of Challen’s eye socket, which is about 300 pixels (Figure 1.12.5).

Figure 1.12.5. Adjusting the brush size

- Brush in the whole area of her face. (At this moment, disregard her eyes.) Compare before the brushwork (Figure 1.12.4) and after brushwork (Figure 1.12.6).

Figure 1.12.4. Before the brushwork

Figure 1.12.6. After the brushwork

- Bring up the Fade effect dialog box (Command + Shift + F / Control + Shift + F). Move the slider first to the left, and then to the right to see if you want less or more effect. For this image, I chose 63%. Click OK. Compare before the brushwork (Figure 1.12.4) and after (Figure 1.12.7).

Figure 1.12.4. Before the brushwork

Figure 1.12.7. After brushwork on her face

- Next, zoom into her eyes by holding down the Command + Space / Control + Space keys and, starting at the upper left part of her face, just above her eyebrow, drag the magnifying glass (in Windows it is a white dot with a + in it) to the lower right part of her face, just under her eye (Figures 1.12.8).

Figure 1.12.8. Focusing on her eyes

- Press the D key, for default (the foreground color is black and the background white), and then the X key (to switch the foreground and background colors), so that you have the foreground color in white. Press the number 0 to set the brush opacity to 100%. Click the left bracket key and set the brush size to 40 pixels. Brush back just Challen’s eyes, specifically their whites and her pupils, and take a look at the layer mask (Figures 1.12.9 and 1.12.10).

Figure 1.12.9. The eyes afer cleaning up the brushwork

Figure 1.12.10. The layer mask

Note

I did the adjustment described above in this manner, because is it is easier to brush back the smaller area than it is to work around it. I always work from the global to the granular.

- Bring the image back to full screen (Command + 0 / Control + 0) and look at your layer mask. You still need to do brushwork on her body and hair. Set your brush to an opacity of 50% (keyboard command 5). Increasing the size of your brush to a diameter of 200 pixels (right bracket key), brush just the outline of her body, and a little in its center. (Again, it is not yet important to be exact.) Bring up the Fade effect dialog (Command + Shift + F / Control + Shift + F) and move the slider left and right to see if you want more or less of the effect. In this case, I chose 32%.

- Option- / Alt-click on the White Point Layer Mask (Figure 1.12.11) and then on the light gray area of Challen’s chest (the area in which you just brushed) to sample the color (Figure 1.12.12). Press the number 0 to set the brush to 100% opacity, and brush in the areas that were missed, tightening up the edges as you go (Figure 1.12.13). This is the quickest, most efficient way that I know to make a layer mask.

Figure 1.12.11.

Figure 1.12.12. Sampling the gray

Figure 1.12.13. The final layer mask

- Next, take care of her hair. Click on the forward slash key (located next to the right bracket key) to bring the image back with the image map layer visible. The White Point layer should still be active, as should the layer mask. Click on the D key to set the foreground/background colors to default, and then click the X key to switch the colors. (The foreground should be black and the background white in the Tools dialog box.) Click the 5 key to set the opacity to 50%, and then the B key for Brush, making sure your layer mask is active. Now paint Challen’s hair according to what you mapped. Once that is done, bring up the Fade effect dialog box (Command + Shift + F / Control + Shift + F) moving the slider right and left to see if you want more or less of the effect. In this case, I chose 50% more. Also, I chose 88% opacity for this part of the image brush back.

- Zoom into the tendrils of her hair on the right side of the image (Figure 1.12.14). Using the left bracket key, shrink the brush size to 40 pixels and brush in the tendrils. Bring up the Fade effect dialog box (Command + Shift + F / Control + Shift + F), and type in 88%.

Figure 1.12.14. Brushing in the tendrils of her hair

That takes care of the white point.

I did not touch the Midpoint Curves adjustment layer, because I liked what that did in this image. That may not be the case in other images, which is why I had you separate the three points into three different adjustment layers—complete control.

Getting the Red Out

The last part of the granular adjustment of this image is to remove the redness from Challen’s eyes (especially where there are blood vessels that show) and to add coolness to the background wall so that it will appear farther back. You will do all this with one Hue and Saturation adjustment layer.

Look at the image map (Figure 1.13.1). You will brush back the right side of the wall, and then the whites of her eyes.

Figure 1.13.1. Image map for removing red

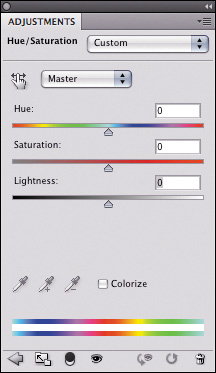

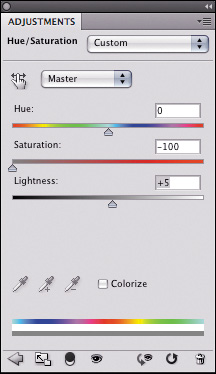

- Create a Hue and Saturation adjustment layer (Figure 1.13.2), and name it EYE/WALL_CORRECTION. If you are using CS4 or above, you can do that with the Adjustments panel. If you are using any version of Photoshop, you can click on the Adjustment Layers icon located at the bottom of the Layers panel (fourth icon from the left—the half black and half white circle). Move the Saturation slider all the way to the left (−100%), which completely removes the color from the image (Figures 1.13.3 and 1.13.4). Next, move the Lightness slider to +5, and fill the Hue and Saturation adjustment layer mask with black.

Figure 1.13.2. Hue/Saturation adjustment

Figure 1.13.4. Setting the Saturation to −100%

Figure 1.13.4. Gray image after the Hue/Saturation adjustment

- Making sure that the layer mask is active, select the Brush tool (keyboard shortcut B). Expand the brush diameter to 600 pixels and set the opacity to 50%. Starting at the top of the image about halfway in, brush to the right, down the right side of the wall, making sure not to do any brushwork on Challen (Figure 1.13.5). Bring up the Fade effect dialog box, and move the slider right and left to see if you want more or less of the effect. I chose 38% (Figure 1.13.6).

Figures 1.13.5 and 1.13.6. Brushwork on right wall and then fading the effect with the Fade effect command

- Zoom into Challen’s face, around her eyes (Figure 1.13.7). Reduce the brush to 20 pixels and make sure that the brush opacity is set to 100%. Brush in all of the white in both of her eyes. You will notice that this is actually a bit too much, but I chose to do this because I wanted the desaturation to be greater in her eyes than in the wall. Also, I wanted to have some color bleed back into her image. One of the many advantages to using adjustment layers is that you can decrease opacity using the Opacity slider located at the top of the Layers panel. I chose 60% for this image. Examine the close-up of her eyes after the adjustment (Figure 1.13.8). Next, color back in the wall (Figure 1.13.9).

Figure 1.13.7. Zooming into Challen’s face

Figure 1.13.8. The eyes after the adjustment

Figure 1.13.9. Brushing in the back wall

- Move the Hue and Saturation adjustment layer above the Midpoint Curves adjustment layer and turn the Midpoint Curves adjustment layer on.

The first part of the granular correction is done. You can see how an image-specific, dynamic workflow is developing. Throughout the course of this book, you should also be aware of how certain decision-making processes allow you to stay as close to the originally captured image data as possible, so as to minimize the cumulative aspects of artifacting, while allowing you to re-create your original vision.

Step 3: Merging Layers in “The Move”

You will now merge the copies of the layers that you have created thus far into a single new layer, while preserving the individual layers that you created earlier. Adobe Photoshop refers to this as Merge Stamp Visible. I prefer to refer to it as doing “The Move.” Note that you are merging the layers into one without flattening the image. This is an important distinction, because if you just merge layers, you also flatten the resultant image and lose all the original layers. This leaves you no exit strategy, and you will be unable to practice at practicing.

Make sure you are at the top of the layer heap by making the topmost visible layer active. Or, if you are working with a layer set, as you are in this image, make the layer set active. In this case, the layer set to make active is BP/WP/MP. For CS3 and above, press and hold Command + Option + Shift + E / Control + Alt + Shift + E. For CS2 and below, press Command + Option + Shift / Control + Alt + Shift, then type N, and then type E.

Note

Do not forget that when doing The Move, all layers that are turned on will be merged into one, both above and below the layer that is active. If after you do The Move, you notice that you have twice the effect that you had before you did it, you had adjustment layers turned on above the active layer or layer set. This is why you want the top layer, or top layer set, to be the active one.

You now have a base image layer on which you can start to work to make other aesthetically pleasing changes. Name it MASTER_1. Click Save As (Command + Shift + S / Control + Shift + S) and name the file SHIBUMI_16BIT. Save the image as a Photoshop document (.psd).

Note