Streams

To save data permanently within a Java program, or to retrieve that data later, you must use at least one stream.

A stream is an object that takes information from one source and sends it somewhere else, taking its name from water streams that take fish, boats, and industrial pollutants from one place to another.

Streams connect a diverse variety of sources, including computer programs, hard drives, Internet servers, computer memory, and DVD-ROMs. After you learn how to work with one kind of data using streams, you are able to work with others in the same manner.

During this hour, you use streams to read and write data stored in files on your computer.

There are two kinds of streams:

• Input streams, which read data from a source

• Output streams, which write data to a source

Java class files are stored as bytes in a form called bytecode. The Java interpreter runs bytecode, which doesn’t actually have to be produced by the Java language. It can run compiled bytecode produced by other languages, including NetRexx and Jython. You also hear the Java interpreter referred to as the bytecode interpreter.

All input and output streams are made up of bytes, individual integers with values ranging from 0 to 255. You can use this format to represent data, such as executable programs, word-processing documents, and MP3 music files, but those are only a small sampling of what bytes can represent. A byte stream is used to read and write this kind of data.

A more specialized way to work with data is in the form of characters—individual letters, numbers, punctuation, and the like. You can use a character stream when you are reading and writing a text source.

Whether you work with a stream of bytes, characters, or other kinds of information, the overall process is the same:

• Create a stream object associated with the data.

• Call methods of the stream to either put information in the stream or take information out of it.

• Close the stream by calling the object’s close() method.

Files

In Java, files are represented by the File class, which also is part of the java.io package. Files can be read from hard drives, CD-ROMs, and other storage devices.

A File object can represent files that already exist or files you want to create. To create a File object, use the name of the file as the constructor, as in this example:

File bookName = new File("address.dat");

This example works on a Windows system, which uses the backslash (\) character as a separator in path and filenames. Linux and other Unix-based systems use a forward slash (/) character instead. To write a Java program that refers to files in a way that works regardless of the operating system, use the class variable File.pathSeparator instead of a forward or backslash, as in this statement:

File bookName = new File("data" + File.pathSeparator + “address.dat”);

This creates an object for a file named address.dat in the current folder. You also can include a path in the filename:

File bookName = new File("data\address.dat");

When you have a File object, you can call several useful methods on that object:

• exists()—true if the file exists, false otherwise

• getName()—The name of the file, as a String

• length()—The size of the file, as a long value

• createNewFile()—Creates a file of the same name, if one does not exist already

• delete()—Deletes the file, if it exists

• renameTo(File)—Renames the file, using the name of the File object specified as an argument

You also can use a File object to represent a folder on your system rather than a file. Specify the folder name in the File constructor, which can be absolute (such as “C:\MyDocuments\”) or relative (such as “java\database”).

After you have an object representing a folder, you can call its listFiles() method to see what’s inside the folder. This method returns an array of File objects representing every file and subfolder it contains.

Reading Data from a Stream

The first project of the hour is to read data from a file using an input stream. You can do this using the FileInputStream class, which represents input streams that are read as bytes from a file.

You can create a file input stream by specifying a filename or a File object as the argument to the FileInputStream() constructor method.

The file must exist before the file input stream is created. If it doesn’t, an IOException is generated when you try to create the stream. Many of the methods associated with reading and writing files generate this exception, so it’s often convenient to put all statements involving the file in their own try-catch block, as in this example:

try {

File cookie = new File("cookie.web");

FileInputStream stream = new FileInputStream(cookie);

System.out.println("Length of file: " + cookie.length());

} catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println("Could not read file.");

}

File input streams read data in bytes. You can read a single byte by calling the stream’s read() method without an argument. If no more bytes are available in the stream because you have reached the end of the file, a byte value of –1 is returned.

When you read an input stream, it begins with the first byte in the stream, such as the first byte in a file. You can skip some bytes in a stream by calling its skip() method with one argument: an int representing the number of bytes to skip. The following statement skips the next 1024 bytes in a stream named scanData:

scanData.skip(1024);

If you want to read more than one byte at a time, do the following:

• Create a byte array that is exactly the size of the number of bytes you want to read.

• Call the stream’s read() method with that array as an argument. The array is filled with bytes read from the stream.

You create an application that reads ID3 data from an MP3 audio file. Because MP3 is such a popular format for music files, 128 bytes are often added to the end of an ID3 file to hold information about the song, such as the title, artist, and album.

On the ASCII character set, which is included in the Unicode Standard character set supported by Java, those three numbers represent the capital letters “T,” “A,” and “G,” respectively.

The ID3Reader application reads an MP3 file using a file input stream, skipping everything but the last 128 bytes. The remaining bytes are examined to see if they contain ID3 data. If they do, the first three bytes are the numbers 84, 65, and 71.

Create a new empty Java file called ID3Reader and fill it with the text from Listing 20.1.

Listing 20.1. The Full Text of ID3Reader.java

1: import java.io.*;

2:

3: public class ID3Reader {

4: public static void main(String[] arguments) {

5: try {

6: File song = new File(arguments[0]);

7: FileInputStream file = new FileInputStream(song);

8: int size = (int) song.length();

9: file.skip(size - 128);

10: byte[] last128 = new byte[128];

11: file.read(last128);

12: String id3 = new String(last128);

13: String tag = id3.substring(0, 3);

14: if (tag.equals("TAG")) {

15: System.out.println("Title: " + id3.substring(3, 32));

16: System.out.println("Artist: " + id3.substring(33, 62));

17: System.out.println("Album: " + id3.substring(63, 91));

18: System.out.println("Year: " + id3.substring(93, 97));

19: } else {

20: System.out.println(arguments[0] + " does not contain"

21: + " ID3 info.");

22: }

23: file.close();

24: } catch (Exception e) {

25: System.out.println("Error — " + e.toString());

26: }

27: }

28: }

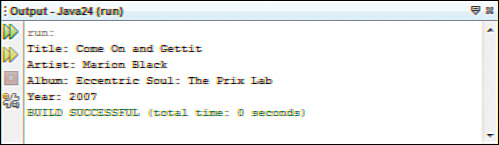

Before running this class as an application, you must specify an MP3 file as a command-line argument. The program can be run with any MP3, such as Come On and Gettit.mp3, the unjustly forgotten 1973 soul classic by Marion Black. If you have the song Come On and Gettit.mp3 on your system (and you really should), Figure 20.1 shows what the ID3Reader application displays.

Figure 20.1. Running the ID3Reader application.

If you don’t have Come On and Gettit.mp3 on your computer (a big mistake, in my opinion), you can look for MP3 songs to examine using the Creative Commons license using Yahoo! Search at http://search.yahoo.com/cc.

Creative Commons is a set of copyright licenses that stipulate how a work such as a song or book can be distributed, edited, or republished. The website Rock Proper, at www.rockproper.com, offers a collection of MP3 albums that are licensed for sharing under Creative Commons.

The application reads the last 128 bytes from the MP3 in Lines 10–11 of Listing 20.1, storing them in a byte array. This array is used in Line 12 to create a String object that contains the characters represented by those bytes.

If the first three characters in the string are “TAG,” the MP3 file being examined contains ID3 information in a format the application understands.

In Lines 15–18, the string’s substring() method is called to display portions of the string. The characters to display are from the ID3 format, which always puts the artist, song, title, and year information in the same positions in the last 128 bytes of an MP3 file.

Some MP3 files either don’t contain ID3 information at all or contain ID3 information in a different format than the application can read.

You might be tempted to find a copy of Come On and Gettit.mp3 on a service such as BitTorrent, one of the most popular file-sharing services. I can understand this temptation perfectly where “Come On and Gettit” is concerned. However, according to the Recording Industry Association of America, anyone who downloads MP3 files for music CDs you do not own will immediately burst into flame. Eccentric Soul is available from Amazon.com, eBay, Apple iTunes, and other leading retailers.

The file Come On and Gettit.mp3 contains readable ID3 information if you created it from a copy of the Eccentric Soul CD that you purchased because programs that create MP3 files from audio CDs read song information from a music industry database called CDDB.

After everything related to the ID3 information has been read from the MP3’s file input stream, the stream is closed in Line 23. You should always close streams when you are finished with them to conserve resources in the Java interpreter.

Buffered Input Streams

One of the ways to improve the performance of a program that reads input streams is to buffer the input. Buffering is the process of saving data in memory for use later when a program needs it. When a Java program needs data from a buffered input stream, it looks in the buffer first, which is faster than reading from a source such as a file.

To use a buffered input stream, you create an input stream such as a FileInputStream object, and then use that object to create a buffered stream. Call the BufferedInputStream(InputStream) constructor with the input stream as the only argument. Data is buffered as it is read from the input stream.

To read from a buffered stream, call its read() method with no arguments. An integer from 0 to 255 is returned and represents the next byte of data in the stream. If no more bytes are available, –1 is returned instead.

As a demonstration of buffered streams, the next program you create adds a feature to Java that many programmers miss from other languages they have used: console input.

Console input is the ability to read characters from the console (also known as the command-line) while running an application.

The System class, which contains the out variable used in the System.out.print() and System.out.println() statements, has a class variable called in that represents an InputStream object. This object receives input from the keyboard and makes it available as a stream.

You can work with this input stream like any other. The following statement creates a buffered input stream associated with the System.in input stream:

BufferedInputStream bin = new BufferedInputStream(System.in);

The next project, the Console class, contains a class method you can use to receive console input in any of your Java applications. Enter the text from Listing 20.2 in a new empty Java file named Console.

Listing 20.2. The Full Text of Console.java

1: import java.io.*;

2:

3: public class Console {

4: public static String readLine() {

5: StringBuffer response = new StringBuffer();

6: try {

7: BufferedInputStream bin = new

8: BufferedInputStream(System.in);

9: int in = 0;

10: char inChar;

11: do {

12: in = bin.read();

13: inChar = (char) in;

14: if (in != -1) {

15: response.append(inChar);

16: }

17: } while ((in != -1) & (inChar != '

'));

18: bin.close();

19: return response.toString();

20: } catch (IOException e) {

21: System.out.println("Exception: " + e.getMessage());

22: return null;

23: }

24: }

25:

26: public static void main(String[] arguments) {

27: System.out.print("You are standing at the end of the road ");

28: System.out.print("before a small brick building. Around you ");

29: System.out.print("is a forest. A small stream flows out of ");

30: System.out.println("the building and down a gully.

");

31: System.out.print("> ");

32: String input = Console.readLine();

33: System.out.println("That's not a verb I recognize.");

34: }

35: }

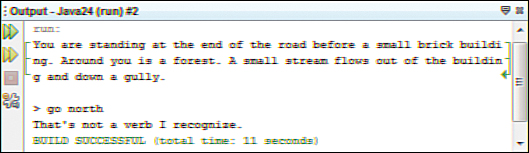

The Console class includes a main() method that demonstrates how it can be used. When you run the application, the output should resemble Figure 20.2.

Figure 20.2. Running the Console application.

The Console class contains one class method, readLine(), which receives characters from the console. When the Enter key is hit, readLine() returns a String object that contains all the characters that are received.

The Console class is also the world’s least satisfying text adventure game. You can’t enter the building, wade in the stream, or even wander off. For a more full-featured version of this game, which is called Adventure, visit the Interactive Fiction archive at www.wurb.com/if/game/1.

If you save the Console class in a folder that is listed in your CLASSPATH environment variable (on Windows), you can call Console.readLine() from any Java program that you write.