Telling the Computer What to Do

A computer program, also called software, is a way to tell a computer what to do. Everything that the computer does, from booting up to shutting down, is done by a program. Windows 7 is a program; Call of Duty is a program; the driver software you installed with your printer is a program; even an email virus is a program.

Computer programs are made up of a list of commands the computer handles in a specific order when the program is run. Each command is called a statement.

If your house had its own butler, and you were a high-strung Type-A personality, you could give your servant a detailed set of instructions to follow:

Dear Mr. Jeeves,

Please take care of these errands for me while I’m out asking Congress for a bailout:

Item 1: Vacuum the living room.

Item 2: Go to the store.

Item 3: Pick up soy sauce, wasabi, and as many California sushi rolls as you can carry.

Item 4: Return home.

Thanks,

Bertie Wooster

If you tell a butler what to do, there’s a certain amount of leeway in how your requests are fulfilled. If California rolls aren’t available, Jeeves could bring Boston rolls home instead.

Computers don’t do leeway. They follow instructions literally. The programs that you write are followed precisely, one statement at a time.

The following is one of the simplest examples of a computer program, written in BASIC. Take a look at it, but don’t worry yet about what each line is supposed to mean.

1 PRINT "Shall we play a game?"

2 INPUT A$

Translated into English, this program is equivalent to giving a computer the following to-do list:

Dear personal computer,

Item 1: Display the question, “Shall we play a game?”

Item 2: Give the user a chance to answer the question.

Love,

Snookie Lumps

Each of the lines in the computer program is a statement. A computer handles each statement in a program in a specific order, in the same way that a cook follows a recipe or Mr. Jeeves the butler follows the orders of Bertie Wooster. In BASIC, the line numbers are used to put the statements in the correct order. Other languages such as Java do not use line numbers, favoring different ways to tell the computer how to run a program.

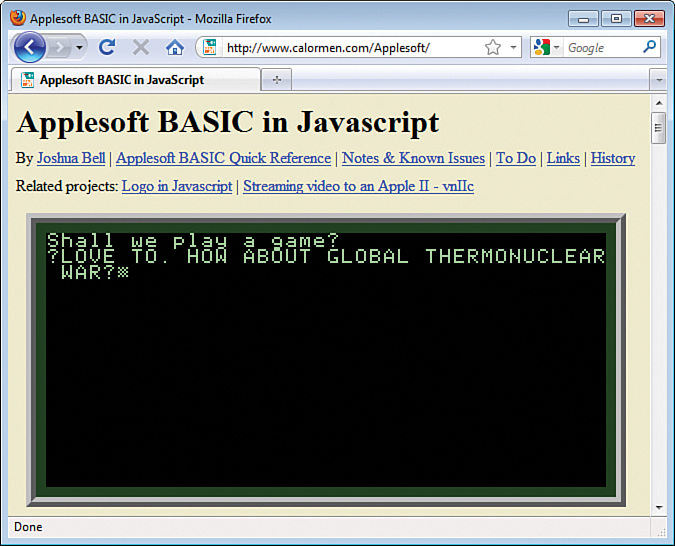

Figure 1.1 shows the sample BASIC program running Joshua Bell’s AppleSoft BASIC interpreter. The interpreter runs in a web browser, and you can find it at www.calormen.com/Applesoft.

Figure 1.1. An example of a BASIC program.

Because of the way programs operate, it’s hard to blame the computer when something goes wrong while your program runs. The computer is just doing exactly what you told it to do. The blame for program errors lies with the programmer. That’s the bad news.

The good news is you can’t do any permanent harm. No one was harmed during the making of this book, and no computers will be injured as you learn how to program in Java.