Chapter 7. Financial Effects of Work-Life Programs

“Remixing” Rewards

Consider some of the ways that the workforce is changing, and how the attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions of employees are shaping today’s workplaces.1

• The composition of the workforce now reflects the growing influence of Generation Y (about 70 million, born between 1979 and 1994), Generation X (about 35 million, born between 1965 and 1978), and Baby Boomers (about 77 million, born between 1946 and 1964).

• Especially among the members of Gen Y and Boomers, flexible work arrangements (89 and 87 percent, respectively) and the opportunity to give back to society (86 and 85 percent, respectively) trump the sheer size of the pay package. That’s not as true for Gen Xers—people in their 30s and early 40s are 10 percent less likely to find this important.

• Fully 87 and 83 percent, respectively, of Gen Yers and Boomers say that work/life fit is important to them. That’s also true of Gen Xers, but to a lesser degree.

• The majority of employees of all generations feel that they do not have enough time for the important aspects of their personal lives.

• Gender roles at home and at work have changed significantly. Women are now in the workforce in almost equal numbers as men, they are just as likely as men to want jobs with greater responsibility, and almost 80 percent of couples are dual earners.

• A climate of respect, a supportive supervisor, and better work-life fit have positive effects on the work, health, and well-being of both men and women of all generations.

• Being treated with respect by managers and supervisors has a stronger effect on the mental health of low-income employees than middle- or high-income employees.

Special Issues Parents Face

Working parents face a host of additional issues:2

• About 70 percent of mothers with school-age children work for pay outside the home, with 55 percent of mothers with infants younger than one year old employed outside the home.

• One in three children is born to a single mother; that group comprises seven million mothers in the United States who do not have a spouse to share the work of earning a livelihood and caring for children.

• More than 1.5 million single fathers are raising children without the financial or emotional support of a spouse. Considered another way, a father heads one in every five single-parent households.

• In 1997, women in dual-earner couples contributed an average of 39 percent of average family income. By 2008, that figure had increased significantly to an average of 44 percent. At the same time, 60 percent of men had annual earnings at least 10 percentage points higher than their spouses/partners, down from 72 percent of men in 1997.

• Men are taking more overall responsibility for care of their children (providing one-on-one care, as well as managing child-care arrangements) according to themselves and their wives/partners. This has led to increased work-life conflict, as 59 percent of fathers in dual-earner couples report experiencing some or a lot of conflict today, up from 35 percent in 1977. Not surprisingly, therefore, 70 percent of men say they would take a pay cut to spend more time with their families, and almost half would turn down a promotion if it meant less family time.3

• At the same time, there is pressure to maintain a two-income lifestyle. Few families can afford “luxuries” such as health insurance, mortgage payments, and grocery bills on one salary. Indeed, more American families file for bankruptcy every year than file for divorce.4

Can organizations enhance both employee productivity and the fit between their work and nonwork lives? When do investments in work and nonwork life fit become a recruitment and retention advantage? Is the advantage actually enough to offset the costs? In short, can investments to enhance the fit between work and nonwork actually pay off, and how much? As in other chapters, our purpose here is to follow the LAMP model presented in Chapter 1, “Making HR Measurement Strategic,” to offer a logical, analytic, and measurement framework regarding work-life programs that might facilitate better decisions about investments in them. We conclude the chapter by providing some practical suggestions about the process of communicating results to decision makers. Let us begin by addressing a simple question: Just what is a work-life program?

Work-Life Programs: What Are They?

Although originally termed “work-family” programs, this book uses the term work-life programs to reflect a broader perspective of this issue. Work-life recognizes the fact that employees at every level in an organization, whether parents or nonparents, face personal or family issues that can affect their performance on the job. A work-life program includes any employer-sponsored benefit or working condition that helps an employee to enhance the fit between work and nonwork demands. At a general level, such programs span five broad areas:5

• Child and dependent-care benefits (for example, on-site or near-site child- or elder-care programs, and summer and weekend programs for dependents)

• Flexible working conditions (for example, flextime, job sharing, teleworking, part-time work, and compressed workweeks)

• Leave options (for example, maternity, paternity, and adoption leaves; sabbaticals; phased re-entry; and retirement schemes)

• Information services and HR policies (for example, cafeteria benefits, life-skill educational programs such as parenting skills, health issues, financial management and retirement, exercise facilities, and professional and personal counseling)

• Organizational cultural issues (for example, an organizational culture that is supportive with respect to the nonwork issues of employees, coworkers, and supervisors who are sensitive to family issues)

Logical Framework

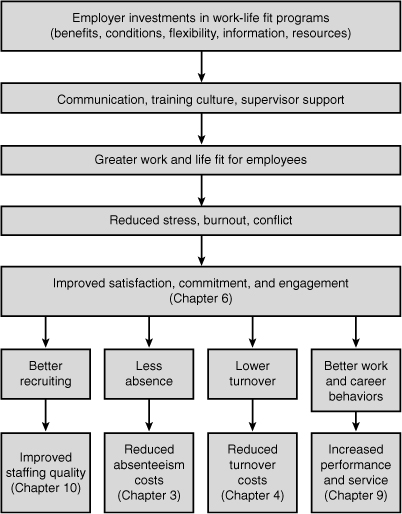

As the chapter-opening statistics make clear, pressures for work-life fit stem from a variety of sources. Whether an organization chooses to address those needs or not, each choice has consequences. Figure 7-1 is a logical framework to describe the conditions that affect the potential impact of work-life programs on behaviors and financial outcomes.

Figure 7-1. Logic of work-life fit.

As Figure 7-1 shows, there are consequences, both behavioral and financial, to decisions to offer or not to offer one or more work-life programs. If an organization chooses not to offer such programs, there may be negative consequences with respect to job performance. Some of these potential impacts include heightened stress, more burnout, a higher likelihood of mistakes, and more refusals of promotions by employees already feeling the strain of pressures for better fit between their work and nonwork lives.

Under these circumstances, job satisfaction, commitment to the organization, and engagement in one’s job (vigor, absorption, dedication—see Chapter 6, “Employee Attitudes and Engagement”) are likely to wane. When that happens, people begin to think about quitting, some actually do quit, and customer service may suffer. All of these consequences lead to significant financial outcomes, as Chapters 3–6 have demonstrated.

Assuming that an organization does offer one or more work-life programs, the financial and nonfinancial effects of those programs depend on several factors. These include the range, scope, cost, and quality of the programs; the extent and quality of communications about the programs to employees; training on how to manage work-life programs; and support for them from managers and supervisors. If those conditions are met, it is reasonable to expect that employees will achieve greater work and life fit. Such fit implies reduced stress, burnout, and conflict, along with increased engagement, satisfaction, and commitment. Those human-capital outcomes lead to improvements in talent management (reductions in withdrawal behaviors and voluntary turnover, and improvements in the ability to attract top talent); motivation to perform well; and financial, operational, and business outcomes. Chapters 3–6 documented some of the financial consequences associated with those outcomes. The following sections elaborate on the elements of Figure 7-1 in more detail.

Impact of Work-Life Strains on Job Performance

Companies can own tangible assets, such as patents, copyrights, and equipment, but they cannot own their own employees.7 Conflicts between job demands and the demands of nonwork life may lead some employees to a condition known as “burnout.” Employees suffering from burnout do the bare minimum, do not show up regularly, leave work early, and quit their jobs at higher rates than less-stressed employees.8 To reduce such tensions, they may leave the workforce altogether or move to positions in other organizations that generate less work-life stress. For firms that are trying to build valuable human assets that are difficult to copy or to lure way, work-life programs may provide powerful retention and performance-enhancement tools.

Other employee-withdrawal behaviors, such as reduced effort while at work, lateness, and absenteeism, also diminish the value of human resources to an employer.9 As shown in Chapter 3, “The Hidden Costs of Absenteeism,” the number-one reason for unscheduled employee absenteeism is personal illness (34 percent). The number-two reason is family-related issues (22 percent). Taken together, these causes account for more than half of all absenteeism incidents. Work-life programs are designed to address precisely these underlying reasons for employee withdrawal. Work-life initiatives that incorporate flexibility into work scheduling, together with “family-friendly” features, can play a potentially important role in protecting a firm’s investment in its human capital. This is especially true for professional employees.

Work-Life Programs and Professional Employees

The view of work-life programs as a strategy for protecting investments in human capital applies particularly well to professional employees. Professional employees are critical resources for organizations because of their expense, their relative scarcity, and the transferability of their skills.10 In addition, professionals tend to be highly autonomous, substituting self-control for organizational control.

Attracting and retaining professionals is difficult because other employers value their skills. Work-life programs can be effective for attracting and retaining these employees.11 Professionals in many countries are delaying the birth of their first child until they have achieved some measure of financial and career security. Given the relatively long years of education and training required of professionals, these people are especially likely to delay starting their families.12 For this reason, work-family tensions tend to rise for many professionals as they reach their 30s and 40s. If organizations fail to provide assistance in handling this tension, they risk losing these valuable employees to employers that offer more flexibility.

From a competitive standpoint, because work-life programs are more highly developed in some organizations than in others, organizations with extensive work-life benefits may be better able to retain top-performing professionals despite efforts by competitors to bid them away. Consider how one public accounting firm does it.13

Offering programs like Crowe, Horwath’s might lead some parents, mostly women, to decide that they don’t have to opt out of the work force temporarily when they have children.

Opting Out

Today many companies recruit roughly equal numbers of female and male MBA graduates, but they find that a substantial percentage of their female recruits drop out within three to five years. The most vexing problem for businesses, therefore, is not finding female talent, but retaining it.14

How large is the opt-out phenomenon? A recent survey examined this phenomenon among 2,443 highly qualified women and a smaller comparison group of 653 highly qualified men (defined as those with a graduate degree, a professional degree, or a high-honors undergraduate degree).15 Fully 37 percent of the women (43 percent of those with kids), as opposed to only 24 percent of the men (no statistical difference between those who are fathers and those who are not), took time off from their careers. Among women, the average break lasted 2.2 years (1.2 years for those in business), with 44 percent citing child- or elder-care responsibilities, compared with only 12 percent of men. Among men, who averaged one year off, the primary reason was career enhancement.

Although 93 percent of the women who took time off from work wanted to return, only 74 percent of them were able to do so. Even then, they paid a high price for their career interruptions, with the penalties becoming more severe the longer the break. Among women in business, the average loss in earnings was 28 percent, even though the average break among those women lasted little more than a year. When women spent three or more years out of the work force, they earned only 63 percent of the salaries of those who took no time out.

The same survey also found that many women cope with job-family tradeoffs by working part time, by reducing the number of hours they work in full-time jobs, and by declining to accept promotions. Women are less likely to opt out of work if their employers offer flexible career paths that allow them to ramp up and ramp down their professional responsibilities at different career points.16 Flexibility is a key retention tool for women as well as for men.

The Toll on Those Who Don’t Opt Out

Especially for those who do not or cannot opt out of working, family and personal concerns are a source of stress:17

• In professional-service firms, well over half the employees can expect to experience some kind of work-family stress in a three-month period.

• Staff members with work-family conflict are three times more likely to consider quitting (43 percent versus 14 percent).

• Staff members who believe that work is causing problems in their personal lives are much more likely to make mistakes at work (30 percent) than those who have few job-related personal problems (19 percent).

• On the other hand, employees with supportive workplaces and supportive supervisors report greater job satisfaction and more commitment to helping their companies succeed.

Organizations want their employees to be highly committed and fully engaged, but in many cases, that is just wishful thinking because of the spillover effect from issues at work to employees’ personal lives off the job. Research has shown that the impact of work on employees’ home lives is fairly well balanced among positive, negative, and neutral.18 Regardless of the direction of the spillover, from work to personal life or from personal life to work, a meta-analytic review found that both types of conflict are negatively related to job and life satisfaction.19

Negative spillover effects are reflected in high stress, bad moods, poor coping, and insufficient quality and amount of time for family and friends. When employees are worried about personal issues outside of work, they become distracted, and their commitment wanes along with their productivity. Ultimately, both absenteeism and turnover (voluntary or involuntary) may increase. As we have noted, family/personal issues are widespread sources of stress, and conflicts between work and personal life affect productivity and general well-being.

The good news, however, is that the impact of employees’ personal or family lives on work is generally positive. Fully half of employees in a large national study reported that their personal or family lives provide them with more energy for their jobs. Only 12 percent reported that their home lives undermined their energy for work, and 38 percent reported a balanced impact of their personal or family lives on their energy levels at work.20 Organizational programs that support work-life fit reinforce these outcomes. Unfortunately, in many organizations, although the programs are available, formidable barriers may make it difficult for employees to use them.21

Enhancing Success Through Implementation

The mere presence of a work-life initiative is no guarantee of success. As shown in Figure 7-1, one must also consider the range, scope, quality, and cost of work-life initiatives, along with the quality and care with which they are deployed. Key factors to consider are the careful alignment of the programs with the strategic objectives of the organization, the extent and quality of communications about the programs, training for managers on how to make the programs work for them, and the extent of management and supervisory support for the programs. If implemented properly, work-life initiatives should reduce employee withdrawal behaviors, increase retention, and increase employees’ motivation to perform well. Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

Both employers and employees have reasons for not using work-life programs. Many supervisors and higher-level managers, for example, think of “work-life” as “work-life equals work less.” They see such programs benefiting employees only and not their organizations.22 The challenge, then, is to help them view work-life initiatives as a new way of working that focuses on fitting work to the employee, not just fitting the employee to the organization’s needs. Training can help them understand what research has shown: The single best predictor of health and well-being at work is work-life fit.23

Employees also have their reasons for not using work-life programs. Researchers in one study used focus groups to investigate why.24 It revealed six major barriers to more widespread use of the programs:

• Lack of communication about the policies (vague or limited knowledge about them)

• High workloads (work builds up when employees take time off)

• Management attitudes (to some managers, employees who take advantage of the policies show lack of commitment; others are unwilling to accommodate differing needs of employees)

• Career repercussions (belief that if employees access work-life policies, their career progression will suffer)

• The influence of peers (fear that employee use of a work-life program will cause resentment or suggest that the employee is not a team player)

• Administrative processes (excessive paperwork and long approval processes)

In short, not just the policies, but also the environment in which they are implemented, make the biggest difference for employees.25 Thus, a nationwide study by Canada’s Department of Labor found that 70 percent of employees surveyed attributed problems with their respective companies’ work-life programs to treatment by their immediate supervisors.26 A follow-up study included a list of 26 items related to work-life fit. Seven of the nine items that were most strongly related to the success of these programs were related to the attitudes and behaviors of supervisors. Indeed, study after study has reinforced the critical role that immediate supervisors play in the overall success of work-life programs.27

An organization that truly is committed to work-life policies does more than simply provide them. It also takes tangible steps to create a workplace culture that supports and encourages the use of the policies,28 and it offers streamlined processes to approve employee access to them. As Figure 7-1 illustrates, those steps include things such as a multichannel communication strategy to promote and publicize the organization’s work-life policies (for example, company intranet, in-house newspaper, e-mail), coupled with training for managers on how to support employees who take advantage of them. For example, that training could be designed around the kinds of behaviors from supervisors that are reflected in just three items from the 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce. Those items are strongly related to employee engagement, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions:29

• My supervisor is supportive when I have a work problem.

• My supervisor recognizes me when I do a good job.

• My supervisor keeps me informed of things I need to know to do my job well.

To break down barriers and to enhance decisions about where investments in work-life programs are likely to have the most significant strategic value, line managers need a logical framework (see Figure 7-1) and research results. Although work-life initiatives are only one determinant of employee behaviors, along with factors such as pay, working conditions, and the work itself, research indicates that they can have substantial effects on employee decisions to stay with an organization and to produce high-quality work. The next section focuses on analytics and measures that make those results meaningful.

Analytics and Measures: Connecting Work-Life Programs to Outcomes

As we pointed out in earlier chapters, the term analytics refers to the research designs and statistical models that allow us to draw meaningful conclusions from studies that purport to show linkages between programs and outcomes. The term measures refers to the actual data that populate those models and the formulas that accompany them. In the case of work-life programs, the measures include the investments in the programs, as well as measures of outcomes such as absence and turnover that are discussed in earlier chapters. The analytical challenges include ensuring that program effects are not confused with other factors (controlling for extraneous effects) and determining correlation and causation.

Child Care

U. S. employers lose an estimated $4 billion annually to absenteeism related to child care.30 Several studies have examined the impact of child-care programs on absenteeism, retention, and return on investment. For example, Citigroup owns or participates in 12 child-care centers in the United States. Employees pay about half the cost to use Citigroup facilities managed by Bright Horizons Family Solutions or at non-Citigroup back-up centers. In two follow-up studies, Citigroup found the following:31

• A 51 percent reduction in turnover among center users compared to noncenter users

• An 18 percent reduction in absenteeism

• A 98 percent retention rate of top performers

Chase Manhattan Bank (now JPMorgan Chase) analyzed the return on investment (ROI) of its backup child-care program (that is, child care used in emergencies or when regular child care is unavailable). It found that child-care breakdowns were the cause of 6,900 days of missed work by parents. Because backup child care was available, these lost days were not incurred. When multiplied by the average daily salary of the employee in question (expressed in 2010 dollars), gross savings were $2,393,015. The annual cost of the backup child-care center was $1,131,170, for a net savings of $1,261,845 and an ROI of better than 110 percent.32

Finally, Canadian financial services giant CIBC recently bulked up its backup child-care program, rolling out the on-site service to 14 Canadian cities. Employees can take advantage of the program for up to 20 days a year at no cost to them. CIBC’s Children’s Care Center has saved more than 6,800 employee days since the first facility opened in 2002. The company estimates its cost savings over that period to be about $1.6 million (in 2010 dollars). Equally important, the program is a big winner with CIBC’s workers.33

Simply offering child care is no guarantee of results like those we have described. Employers considering offering such a benefit should understand child-care service delivery, the cost of care and its availability, what is available in the local market, and any challenges it presents. In addition, employers need to consider the business case for offering child care.34 Depending on the nature of the business, the goal may be to improve recruitment and retention, support the advancement of women, reduce absenteeism, retain high performers, or be an employer of choice. Then measure what matters, considering key drivers of the business and the goals established for the program.

Flexible Work Arrangements

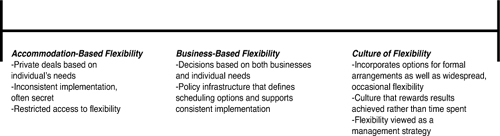

When one stops to consider the effects of e-mail, smart phones, personal and family demands, and the 24/7 business environment, the inescapable conclusion for many employees is that 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. just isn’t working anymore. Time is employees’ most precious commodity. They want the flexibility to control their own time—where, when, and how they work. They want a better fit in their lives between work and leisure. Flexibility in schedules is important, as organizations strive to retain talented workers. Indeed, a recent survey of 182 organizations primarily in the U.S. and Canada revealed that 90 percent offer one or more flexible work arrangements to employees.35 It is important to emphasize, however, that the concept of “flexibility” reflects a broad spectrum of possible work arrangements, as Figure 7-2 makes clear.

Figure 7-2. Implementing flexibility: A spectrum of practice.

In terms of specific initiatives, here are six broad categories of flexible work arrangements.36

- Choices in managing time, which includes control over one’s schedule and satisfaction with one’s schedule

- Flex time and flex place, which includes traditional flexibility, daily flexibility, and shift work, compressed workweeks, and working at home

- Reduced time, which includes part-time and part-year work

- Time off for small necessities, one’s own or family members’ illnesses, vacations and holidays, and volunteer work

- Caregiving leave, which includes maternity and paternity leave

- Culture of flexibility, which includes perceived jeopardy, supervisor support, and general obstacles for using flexibility

Research has revealed that 87 percent of employees at all levels say they want increased flexibility at work. These include employees from low-income families (median annual income of $15,600), middle-income families (median annual income of $62,400), and high-income families (median annual income of $140,400).37 In terms of job levels (executives, managers, and professionals), the two most common flexible work arrangements are telework and flex time. Depending on the level of employee, 56–72 percent of companies offer these options. Among hourly and nonexempt employees, the following percentages of companies offer these options: flex time (49 percent), part-time work (42 percent), and telework (33 percent).38

Earlier we noted some key barriers to wider implementation of work-life programs. Flexible work schedules are no exception. “Flexibility is frequently viewed by managers and employees as an exception or employee accommodation, rather than as a new and effective way of working to achieve business results. A face-time culture, excessive workload, manager skepticism, customer demands, and fear of negative career consequences are among the barriers that prevent employees from taking advantage of policies they might otherwise use—and that prevent companies from realizing the full benefits that flexibility might bestow.”39

To help inform the debate about flexible work arrangements, consider the financial and nonfinancial effects that have been reported for these key outcomes shown in Figure 7-1: talent management (specifically, better recruiting and lower turnover) and human-capital outcomes (increased satisfaction and commitment, decreased stress), which affect cost and performance, leading to financial, operational, and business outcomes. Here are some very brief findings in each of these areas, from a recent study of 29 American firms.40

Talent Management

IBM’s global work-life survey demonstrated that, for IBM employees overall, flexibility is an important aspect of an employee’s decision to stay with the company. Responses from almost 42,000 IBM employees in 79 countries revealed that work-life fit—of which flexibility is a significant component—is the second-leading reason for potentially leaving IBM, behind compensation and benefits. Conversely, employees with higher work-life fit scores (and, therefore, also higher flexibility scores) reported significantly greater job satisfaction and were much more likely to agree with the statement “I would not leave IBM.”

In the corporate finance organization, 94 percent of all managers reported positive impacts of flexible work options on the company’s “ability to retain talented professionals.” In light of these findings showing the strong link between flexibility and retention, IBM actively promotes flexibility as a strategy for retaining key talent.

Human-Capital Outcomes: Employee Commitment

At Deloitte & Touche, one employee survey item asked whether employees agreed with the statement “My manager grants me enough flexibility to meet my personal/family responsibilities.” Those who agreed that they have access to flexibility scored 32 percent higher in commitment than those who believed they did not have access to flexibility. Likewise, AstraZeneca found that commitment scores were 28 percent higher for employees who said they had the flexibility they needed, compared to employees who did not have the flexibility they needed.

Financial Performance, and Operational and Business Outcomes: Client Service

Concern for quality and continuity of client or customer service is often one of the concerns raised about whether flexibility can work in a customer-focused organization. To be sure that compressed workweeks did not erode traditionally high levels of customer service, the Consumer Healthcare division of GlaxoSmithKline surveyed customers as part of the evaluation of its flexibility pilot program. Fully 89 percent of customers said they had not seen any disruption in service, 98 percent said their inquiries had been answered in a timely manner, and 87 percent said they would not have any issues with the program becoming a permanent work schedule.

Studies such as these make it possible to reframe the discussion and to position flexibility not as a “perk,” employee-friendly benefit, or advocacy cause, but as a powerful business tool that can enhance talent management, improve important human-capital outcomes, and boost financial and operational performance.41

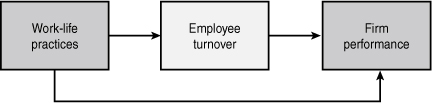

Work-Life Policies and Firm Performance

A large-scale, empirical study of data from a series of surveys administered by the Ministry of Manpower, Singapore, from 1996 to 2003, investigated the indirect impact of work-life practices through employee turnover and the direct impact of work-life practices on firm performance.42 The researchers defined firm performance in three ways: financial (return on assets [ROA]), employee productivity (logarithm of sales per employee), and investor return (one-year compounded stock-price return). What is unique about this study, relative to prior research, is that most prior research has examined the effects of work-life programs on employee turnover within a single firm. Data on employee turnover across a large sample of firms, in this study, 2,570 firms, is not easily available, and therefore has not been examined.

Work-Life Practices in Singapore

Employee benefits in Singaporean firms fall into two main categories: work-life benefits and resource benefits. Work-life benefits refer to benefits that allow employees to adjust their work hours or work location to accommodate their personal and family demands, such as various leave benefits and flexible working arrangements. Resource benefits refer to financial and other resources that firms give to employees, either as a form of welfare benefit or as performance incentives, such as transportation benefits and stock options.

The researchers analyzed data separately for management and nonmanagement employees. In addition, they examined four variables to indicate the extensiveness of work-life benefits in a firm:

• Number of work-life benefits (controlling for number of resource benefits)

• Annual leave entitlement

• Workweek pattern (compressed versus standard)

• Availability of part-time employment

Figure 7-3 presents the design of the study.

Figure 7-3. Relationships between work-life variables, employee turnover, and firm performance.

As Figure 7-3 shows, the design of the study allowed the researchers to investigate the indirect impact of work-life practices through employee turnover and the direct impact of work-life practices on firm performance. They controlled for the size of the firm, ownership (publicly listed or private), industry (manufacturing or service), degree of industry concentration, and year (where multiple years of data were used). For stock return, they also controlled for the age of the firm and the systematic risk of the firm’s stock (beta).

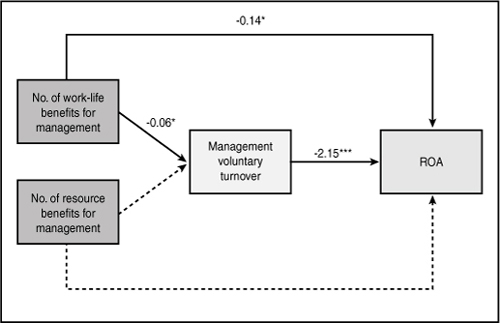

Figure 7-4 shows a typical result of the analysis.

Figure 7-4. Relationships between number of work-life benefits and number of resource benefits for management, management voluntary turnover, and ROA.

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Source: Kelly, K., and S. Ang, A Study on the Relationships between Work-Life Practices and Firm Performance in Singapore Firms, technical report, Nanyang Business School. Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, October 2005.

Based on 1,178 observations from the year 2003, and controlling for the number of resource benefits, firms that offer more work-life benefits for management employees have lower management voluntary turnover (standardized regression coefficient = –0.06). In turn, firms with lower management voluntary turnover generate higher ROA (standardized regression coefficient = –2.15). Hence, the indirect effect of the number of work-life benefits for management on ROA through turnover is positive (–0.06 × –2.15).

However, there is also a direct negative relationship between the number of work-life benefits for management and return on assets (standardized regression coefficient = –0.14), suggesting that implementing work-life benefits for management is financially costly for firms.

Overall Summary of Results

The results of this study indicate that voluntary turnover among managers as well as rank-and-file employees negatively affects firm financial performance, employee productivity, and investor return. Conversely, implementing work-life initiatives for both management and rank-and-file employees can be an effective business strategy for firms to reduce voluntary employee turnover. While the effects of reduced turnover do not quite offset the direct financial costs, reduced turnover is only one effect of work-life programs. The study found lower voluntary employee turnover in these firms:

• Firms that offer a larger number of work-life benefits to their employees

• Firms that have a higher proportion of employees with more generous annual leave entitlements

• Firms that have a higher proportion of employees on shorter workweeks

After reading these results, you may well be wondering what causes what. That is, do work-life programs drive reductions in employee turnover, or do firms with low turnover rates find it viable to invest in work-life programs? Fortunately, the results of a recent large-scale, longitudinal study have begun to shed light on this important issue.43 Using data from 885 private-sector businesses in multiple industries over five years, researchers found multidirectional (reciprocal) relationships between firm performance (ROA) and both voluntary and involuntary turnover. That means that turnover was higher in poorer-performing firms, and that this was due both to poor firm performance causing employees to leave and to high employee turnover causing poorer firm performance. Furthermore, employee benefits moderated the negative relationships between firm performance and both voluntary and involuntary turnover. That means that employees in firms that offered a larger number of employee benefits were less likely to leave voluntarily when firm performance was poor. Correspondingly, firms that offered a larger number of employee benefits were less likely to respond to poor firm performance by terminating employees involuntarily.

What are the practical implications of these findings? Anticipate a possible spike in voluntary turnover when a firm performs poorly, but recognize that work-life benefits may offset that trend.

Stock Market Reactions to Work-Life Initiatives

A recent study examined stock market effects of 130 announcements among Fortune 500 companies of work-life initiatives in The Wall Street Journal.44 The study examined changes in share prices the day before, the day of, and the day after such announcements. The average share price reaction over the three-day window was 0.39 percent, and the average dollar value of such changes was approximately $60 million per firm.

Apparently, investors anticipate that firms will have access to more resources (such as higher-quality talent) following the adoption of a work-life initiative. There is a difference, however, between announcements and actual implementation. Only firms that do what they say they will do are likely to reap the benefits of work-life initiatives.

In another study, researchers used data from 1995 to 2002 to compare the financial and stock market performance of the “100 Best” companies for working mothers, as published each year by Working Mother magazine, to that of benchmark indexes of the performance of U.S. equities, the S&P 500, and the Russell 3000.45 In terms of financial performance, expressed as revenue productivity (sales per employee) and asset productivity (ROA), the study found no evidence that Working Mother “100 Best” companies were consistently more profitable or consistently more productive than their counterparts in S&P 500 companies.

At the same time, however, the total returns on common stock among Working Mother “100 Best” companies consistently outperformed the broader market benchmarks in each of the eight years of the study. Although the researchers found no evidence to indicate that “100 Best” companies are handicapped in the marketplace by offering generous work-life benefits, companies with superior stock returns may have a lower cost of capital and, therefore, can afford to invest in such benefits. The results reflect associations, not causation, between firms that adopt family-friendly work practices and financial and stock market outcomes. Nonetheless, the results suggest the possibility that at least some of the association is due to the effects of family-friendly investments on market outcomes.

Process

In this chapter, you have read facts and interview results that describe work-life fit/misfit. You have also seen data that reflect both financial and nonfinancial effects of work-life programs. In this final section, we present some guidelines to help you inform decision makers in a systematic way about the costs and benefits of such programs. Let’s begin with a general query: What does it all mean?

If the findings described at the beginning of this chapter generalize widely, it is clear that employees at all levels, both men and women, and the members of different generations, want a “new deal” at work. To advance this agenda, leaders need to take four actions:46

• Stop defining the desire for “doable” jobs as a women’s issue. Men want this, too.

• Start viewing efforts to humanize jobs as a competitive advantage and business necessity, not as one-time accommodations for favored employees or executives.

• Realize that progress is actually possible and that many examples show that work at all levels can be retooled.

• Make it safe within your organization to talk about these issues. As former Xerox CEO Anne Mulcahy noted wryly, “Businesses need to be 24/7; individuals don’t.”47

Influencing Senior Leaders

Remember that the purpose of HR metrics is to influence decisions about talent and how it is organized. To do that, senior leaders have to buy in to the logic and analyses that underlie the adoption of work-life programs. At a general level, here is a three-pronged strategy to consider in securing that kind of buy-in:48

- Make the business case for work-life initiatives through data, research, and anecdotal evidence.

- Offer to train managers on how to use flexible management approaches—to understand that, for a variety of reasons, some people want to work long hours, way beyond the norm, but that’s not for everybody. The objective is to train managers to understand that individual solutions will work better in the future than a one-size-fits-all approach.

- Use surveys and focus groups to demonstrate the importance of work-life fit in retaining talent.

Recognize that no one set of facts and figures applies to all firms. It depends on the unique strategic priorities of each organization. Figure 7-1 provides a diagnostic logic for conversations about this. One might start by discussing whether such initiatives will be part of a recruitment strategy to help the organization become an employer of choice, a diversity strategy to promote the advancement of women and minorities, a total rewards strategy, a strategy to retain top talent, or a health and wellness strategy if the priority is stress reduction.49 Find out what your organization and its employees care about right now, what the workforce will look like in three to five years, and therefore, what senior leaders will need to care about in the future.50

Second, don’t rely on isolated facts. By itself, any single study or fact is only one piece of the total picture. Think in terms of a multipronged approach:

• External data that describe trends in your organization’s own industry

• Internal data that outline what employees want and how they describe their needs.51

• Internal data, perhaps based on pilot studies, that examine the financial and nonfinancial effects of work-life programs. As one executive noted, “Nothing beats a within-firm story.”52

Be sure to communicate the high costs of employee absenteeism and turnover to employers (see Chapters 3 and 4). For example, because most costs associated with employee turnover are hidden (separation, replacement, and training costs), many firms do not track them. With these costs identified, communicate the benefits of work-life initiatives in reducing them.

Include stories from your own workers that describe how work-life programs have helped them. Have quotes from people whom senior leaders know and care about. In other words, use a combination of quantitative and qualitative data to make your case.

Third, understand that decision makers may well be skeptical even after all the facts and costs have been presented to them. Perhaps more deeply rooted attitudes and beliefs may underlie the skepticism—such as a belief that allowing employees to attend to personal concerns through time off may erode service to clients or customers, or that people will take unfair advantage of the benefits, or that work-life issues are just women’s issues. To inform that debate, HR leaders need to address attitudes and values, as well as data, on costs and benefits of work-life programs. As one set of authors noted:

Every workplace, small or large, can undertake efforts to treat employees with respect, to give them some autonomy over how they do their jobs, to help supervisors support employees to succeed on their jobs, and to help supervisors and coworkers promote work-life fit.53

Ultimately, a system of work-life programs, coupled with an organizational culture that supports that system, will help an organization create and sustain competitive advantage through its people.

Exercises

- Your boss is skeptical about claims that work-life fit is important to managers as well as employees. What evidence can you provide to offset this line of thinking?

- What is a work-life program? What are some examples?

- Describe the wage penalty associated with “opting out” of the workforce.

- Why is work-life fit particularly important to professional employees?

- Describe some of the key barriers to wider implementation of work-life programs.

- Develop a strategy for informing the debate over whether to invest in work-life programs. What cautions would you build into your game plan?

- Explain: The concept of “flexibility” reflects a broad spectrum of possible work arrangements.

- What key features are critical to making decisions about whether to provide options for increased flexibility in work arrangements?

- How do work-life programs relate to organizational performance?

- You are given the following data regarding the costs and payoffs from employer-subsidized child-care arrangements in your 159-person professional services organization. Before offering child-care, employees missed 850 days of work each year. That has been cut by 170 days per year, at a cost savings of $315 per day in direct costs. Likewise, voluntary turnover among high performers has dropped by 22 percent, saving the company $1.1 million each year in costs that were not incurred. The full cost of the child-care program (design and delivery) is $650,000. What is the ROI of this investment?

References

1. Hewlett, S. A., L. Sherbin, and K. Sumberg, “How Gen Y and Boomers Will Reshape Your Agenda,” Harvard Business Review 87 (July/August 2009): 3–9. See also Galinsky, E., K. Aumann, and J. T. Bond, The 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce: Times Are Changing—Gender and Generation at Work and at Home (New York: Families and Work Institute, 2009); Aumann, K., and E. Galinsky, The 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce: The State of Health of the American Workforce: Does Having an Effective Workplace Matter? (New York: Families and Work Institute, 2009). See also Minton-Eversole, T., “Survey: In Hiring Game, Employers Attuned to Work/Life Balance Win,” HR News (February 28, 2008). Downloaded from www.shrm.org on May 21, 2010.

2. Galinsky, E., et al., 2009. See also Halpern, D. F. (chair), Public Policy, Work, and Families: Report of the APA Presidential Initiative on Work and Families (Washington, D. C.: American Psychological Association, 2005); and Halpern, D. F., and S. E. Murphy, From Work-Family Balance to Work-Family Interaction: Changing the Metaphor (Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum, 2005).

3. Brady, D., “Hopping Aboard the Daddy Track,” BusinessWeek (November 8, 2004), 100–101.

4. Warren, E., and A. W. Tyagi, The Two-Income Trap: Why Middle-Class Mothers and Fathers Are Going Broke (New York: Basic Books, 2003).

5. Sammer, J., “Generating Value through Work/Life Programs,” June 2004, retrieved from www.shrm.org on June 1, 2010; and Bardoel, E. A., P. Tharenou, and S. A. Moss, “Organizational Predictors of Work-Family Practices,” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 36, no. 3 (1998): 31–49.

6. Sources: Moskowitz, M., R. Levering, and C. Tkaczyk, “100 Best Companies,” Fortune (February 8, 2010), 75; “SAS Revenue Jumps 2.2% to Record $2.31 Billion” (January 21, 2010), downloaded from www.sas.com May 28, 2010; and “SAS Ranks No. 1 on Fortune ‘Best Companies to Work For’ List in America” (January 21, 2010), downloaded from www.sas.com on May 28, 2010.

7. Fueling the Talent Engine: Finding and Keeping High Performers: A Case Study of Yahoo! DVD (Alexandria, Va.: Society for Human Resource Management Foundation, 2005); and Coff, R. W., “Human Assets and Management Dilemmas: Coping with Hazards on the Road to Resource-Based Theory,” Academy of Management Review 22 (1997): 374–403.

8. Maslach, C., and M. P. Leiter, “Early Predictors of Job Burnout and Engagement,” Journal of Applied Psychology 93 (2008): 498–512; and Maslach, C., “Understanding Burnout: Work and Family Issues,” in From Work-Family Balance to Work-Family Interaction: Changing the Metaphor, ed. D. F. Halpern and S. E. Murphy (Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum, 2005).

9. Konrad, A. M., and R. Mangel, “The Performance Effect of Work-Family Programs,” paper presented at the annual convention of the Academy of Management, San Diego, August 1998.

11. Byrnes, N., “Treating Part-Timers Like Royalty,” BusinessWeek (October 10, 2005), 78.

13. “Taxing Time: Accounting Firm Maintains Work/Life Balance During Busy Season,” March 10, 2010, downloaded from www.shrm.org on May 25, 2010.

14. Tyson, L. D., “What Larry Summers Got Right,” BusinessWeek (March 28, 2005), 24.

15. Hewlett, S. A., and C. B. Luce, “Off-Ramps and On-Ramps: Keeping Talented Women on the Road to Success,” Harvard Business Review 83 (March 2005): 43–54.

17. Johnson, A. A., “Strategic Meal Planning: Work/Life Initiatives for Building Strong Organizations,” paper presented at the conference on Integrated Health, Disability, and Work/Life Initiatives, New York, February 25, 1999.

18. Galinsky, Aumann, and Bond, 2009.

19. Kossek, E. E., and C. Ozeki, “Work-Family Conflict, Policies, and the Job-Life Satisfaction Relationship: A Review and Directions for Organizational Behavior–Human Resources Research,” Journal of Applied Psychology 83 (1998): 139–149.

20. Galinsky, Aumann, and Bond, 2009.

21. De Cieri, H., B. Holmes, J. Abbott, and T. Pettit, “Achievements and Challenges for Work/Life Balance Strategies in Australian Organizations,” International Journal of Human /Resource Management 16, no. 1 (2005): 90–103.

22. “Expert: Work-Life Initiatives Start at the Top,” September 26, 2008), downloaded from www.shrm.org, May 25, 2010.

23. Aumann and Galinsky, 2009.

24. Waters, M. A., and E. A. Bardoel, “Work-Family Policies in the Context of Higher Education: Useful or Symbolic?” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 44, no. 1 (2006): 67–82.

25. Blair-Loy, M., and A. S. Wharton, “Employees’ Use of Work-Family Policies and the Workplace Social Context,” Social Forces 80, no. 3 (2002): 813–845.

26. Canadian Department of Labor, “Voices of Canadians: Seeking Work-Life Balance,” 2003, downloaded from http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection/RH54-12-2003E.pdf, June 1, 2010.

27. Murphy and Zagorski, 2005. See also Zagorski, D. A., “Balancing the Scales: The Role of Justice and Organizational Culture in Employees’ Search for Work-Life Equilibrium,” unpublished doctoral dissertation, Claremont Graduate University, 2005.

28. Waters and Bardoel, 2006; Hewlett and Luce, 2005.

29. Aumann and Galinsky, 2009.

30. Gurschiek, K., “Child Care ‘Investment’ Creates Competitive Advantage,” HR News, March 5, 2007, downloaded from www.shrm.org, May 25, 2010.

32. O’Connell, B., “No Baby Sitter? Emergency Child-Care to the Rescue,” Compensation & Benefits Forum. Retrieved from www.shrm.org, May 25, 2010.

33. Shellenbarger, S., “If You’d Rather Work in Pajamas, Here Are Ways to Talk the Boss into Flex-Time,” The Wall Street Journal (February 13, 2003), D1; and Conlin, M., J. Merritt, and L. Himelstein, “Mommy Is Really Home from Work,” BusinessWeek (November 25, 2002), 101–104.

35. Culpepper and Associates, “Flexible Work Arrangements: Popular Alternatives to Enhance Benefits,” June 26, 2009, downloaded from www.shrm.org, May 25, 2010; Corporate Voices for Working Families, “Business Impacts of Flexibility: An Imperative for Expansion,” November 2005, downloaded from www.cvworkingfamilies.org/system/files/Business%20Impacts%20of%20Flexibility.pdf, June 1, 2010.

36. Galinsky, E., K. Aumann, and J. T. Bond, The 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce: Workplace Flexibility and Employees from Low-Income Households (New York: Families and Work Institute, 2010).

38. Culpepper and Associates, 2009.

39. Corporate Voices for Working Families, 2005.

42. Kelly, K., and S. Ang, “A Study on the Relationships between Work-Life Practices and Firm Performance in Singapore Firms,” technical report, Nanyang Business School, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, October 2005.

43. Kelly, K., S. Ang, G. H. H. Yeo, and W. F. Cascio, “Employee Turnover and Firm Performance: Modeling Reciprocal Effects,” manuscript currently under review.

44. Arthur, M., “Share Price Reactions to Work-Family Initiatives: An Institutional Perspective,” Academy of Management Journal 46 (2003): 497–505.

45. Cascio, W. F., and C. Young, “Work-Family Balance: Does the Market Reward Firms That Respect It?” in From Work-Family Balance to Work-Family Interaction: Changing the Metaphor, ed. D. F. Halpern and S. E. Murphy (Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2005).

46. Miller, J., and M. Miller, “Get a Life!” Fortune (November 28, 2005): 110.

48. “Expert: Work-Life Initiatives Start at the Top,” 2008.

50. Pires, P. S., “Sitting at the Corporate Table: How Work-Family Policies Are Really Made,” in From Work-Family Balance to Work-Family Interaction: Changing the Metaphor (Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum, 2005).

51. Caminiti, S., “Reinventing the Workplace,” Fortune (September 20, 2004): S12–S15.

52. Roberts, B., “Analyze This!” HR Magazine (October 2009), 35–41.