5. Write Simply and Clearly

You’re waiting in the airport when you hear the bad news over the PA system: Your departure has been delayed for two hours. So, with time to kill, you head to the newsstand and browse the magazine racks. Here’s some good news: Those magazines are not just entertainment; they’re also inspiration for how to write HR content simply and clearly. The same techniques that editors use to get you to read their magazines, advertisers also use to encourage you to buy their products and newspapers use to inform you—all work equally well in the world of HR communication.

That’s because effective writing follows universal principles. Employees do not differentiate how they react to communications at work versus at home. They don’t say, “This isn’t easy to understand, but that’s okay, because it’s just from my company.” They don’t say, “The company video with those talking heads was boring, but I watched it anyway,” because they wouldn’t watch a boring movie at home. They wouldn’t read a long, rambling, complex article online or in print, and they won’t do that at work either.

Earn Points for Doing It Well

When you write in short, easy-to-read, conversational language that everyone can understand, everyone will. We show you how, in five simple steps:

1. Convey what matters most to employees.

3. Slice, dice, and chunk content.

5. Be concrete.

Convey What Matters Most to Employees

In Chapter 4, “Frame Your Message,” we showed you how to develop a “high concept” to summarize your key message, and how to use the inverted pyramid to organize your message. We also shared an important reporters’ tool—five Ws and an H, which is used in journalism to convey essential facts. We think the five Ws and an H are so integral to successful writing that we’re showing them to you again:

• Who: The subject of your communication

• What: The action: what action will occur, what needs to happen

• When: The date the change will occur

• Where: The location(s)

• Why: The motivation behind or reason for the action

• How: The process and method of the action

Here’s the key: As you capture the five Ws and an H, focus on the employee. Ask and answer these questions from the employee’s point of view:

• Why is this important?

• What do I need to do?

• When do I need to act?

Put that important information up front in your communication, and then reinforce this information throughout: in photo captions, subheads, callout quotes, stories, tables, and charts.

Emphasize “How To”

Remember that scene in the airport newsstand when your flight was delayed and you were looking at magazines? If you meandered over to the section with consumer magazines—such as Good Housekeeping, Men’s Health, Better Homes and Gardens, Bon Appetit, and Seventeen—you might have noticed something about the “cover lines” (the short headlines that promote what’s inside that issue). Here’s a sampling of what you might have seen:

• How one “Biggest Loser” really lost 140 pounds

• Banish beauty blunders

• Drop a dress size in 6 weeks

• Make dinner like a pro—in just 30 minutes

• 7 success strategies your CEO doesn’t want you to know

• Sleep deeply | Wake up energized

• How to love a crazy job

• Your best spring garden ever

What do these cover lines have in common? They promise to help readers solve a problem, improve something they do, and, fundamentally, be happier. Magazine editors use these lines because they know that “you” and “how to” are the most compelling headline words you can use. They’re so compelling, in fact, that they work even if you don’t explicitly use them. (“Sleep deeply” is short for “Here’s how you can sleep deeply.” We get that “you” and “how to” are implied.)

The official name for this approach is “service journalism,” explains Don Ranly, professor emeritus at the University of Missouri School of Journalism. We often quote Dr. Ranly because he has such good advice about how to present information. The idea behind service journalism is that you (the writer) perform a service for the reader by putting together useful “how to” information. In other words, if you package information in a way that is useful for readers, they will be more likely to use that information to take action.

(Don also calls this technique “refrigerator journalism” because people cut out or print useful articles and post them where they will see them every day—on the refrigerator door.)

In short, the secret that advertisers and magazine editors know is that people crave information that makes things easier, simpler, faster, and better. So if you write your messages that way, employees will pay attention.

Write “Benefit” Headlines Like Advertisers Do

Advertisers know that the most successful headlines are what they call “benefit” heads: headlines that tell you what benefits their products offer you, such as give you softer skin or whiter teeth. (Smart advertisers don’t emphasize a product’s “features,” such as the number of servings or list of ingredients, because customers don’t find those as appealing.)

While HR programs rarely give employees softer skin, most HR “products” do offer employees tangible benefits. So your headlines should focus on those benefits, not list the features.

For example, a feature of your retirement plan may be that it offers employees eight different investment funds. A benefit of your retirement plan may be that the company matches employee contributions dollar for dollar. Which will appeal most to employees? Here are two headlines. Which do you think most employees will be drawn to?

• “Our retirement plan offers you eight different investment options”

• “How you can be paid to save” or “How to double your savings”

Tell Readers “How To”

Luckily, HR information lends itself to service journalism because it personally affects employees, and there’s often a how-to component.

Here are some examples of how to follow Don’s advice to create headlines that provide a service for your employees. (All would engage employees’ interest much more than a bland heading like “Your Medical Plan.”)

• Money (subhead: How you can make more of it and save for tomorrow)

• How to make sound investment decisions

• How to decide what amount of life insurance you need

• 5 ways to increase your productivity without leaving your workstation

• How flexible work arrangements create a win-win for you and your employer

• 3 steps to choose your best medical coverage

Use Odd Numbers for Maximum Retention

A noted writer with lots of experience in the business press once confided this wonderful little secret to us: Odd numbers are more memorable than even numbers. That’s why you’ll find lots of “3 ways to...” and “5 things to remember...” and “7 ways to solve a problem” in our collected works.

Slice, Dice, and Chunk Content

No, we won’t give you a cooking lesson or try to sell you one of those infomercial products (“It slices! It dices! It does your laundry!”). Instead, we show you how to cut your copy into manageable chunks so that employees quickly get your message.

The bad news you know already:

People do not read!

The next time someone wants to communicate complicated information in great detail, remind him or her of the following facts:

• Most people read only headlines and the first paragraphs.

• People are likely to stop reading if materials include words they don’t understand.

• Most employees spend less than one minute reading a newsletter.

• It takes an average reader one minute to read 200 words.

• Web readers read 25% slower and scan 79% of the time, reading only 20% to 28% of the words. Only 16% read word for word.

We need to “chunk” because we’ve become a society of skimmers and scanners, glancing through a print publication or browsing in a website to find what we need quickly. We read shorter chunks of information more readily than we will read huge, gray columns of words with no break in sight.

As a result, communicators need to find ways to package our content into “chunks” that make it easy for our audience to dive in and remember information.

For example, you’ll notice that we liberally use bullet points throughout this book. That’s because bullets help you do the following:

• Present an easy-to-scan list of words

• Give readers a series of instructions

• Divide a long, complex sentence into discrete select points

We just showed you an example of what happens if you take a long sentence and divide it so that each bullet starts with a verb. That’s another hidden benefit of bullets: They beg for parallel construction that creates a nice, easy rhythm for the reader. We prefer to use verbs as the starting point for bullets because verbs communicate action.

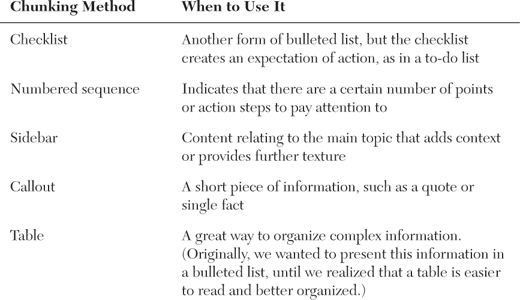

Of course, bullets aren’t the only way to chunk your content. You can also try the following:

Axe the Deadwood

Another way to reduce copy into meaningful chunks is to axe the deadwood. Whenever you see an empty word or phrase, replace it or delete it. Pretend every word costs you one dollar out of your paycheck, and suddenly, you’ll find yourself editing like never before. For example, cross out every “In the event of” you see and replace it with the wonderfully brief equivalent “If . . . .”

A good rule is that if you would not say a phrase aloud to another person, don’t put it in writing.

Open the LATCH to Organize Your Writing Better

Need help figuring out how to create a bulleted list, checklist, or table? We gain inspiration from Richard Saul Wurman, author of Information Anxiety,1 who notes that there are five, and only five, ways to organize information. They are best remembered by the acronym LATCH, which stands for the following:

• Location. This describes where certain things are in relation to others. For example, during orientation to a new job, it’s useful for an employee to know where the cafeteria and restroom are, and where to find various departments or offices.

• Alphabet. This isn’t a great way to organize a grocery store, but it sure makes sense on the spice rack. Many topics benefit from being looked at from A to Z.

• Time. The timeline is a great way to present historical information or to project into the future. It is an especially good device to summarize what benefits kick in when, or to show what happens to some benefits while an employee works for the company and when he retires.

• Category. Most stores organize similar items together. This technique also works well when you’re writing about certain HR programs, policies, or benefits. For example, a communication about time off might include programs that are administered by several different HR departments, but that distinction isn’t of interest to an employee. She just wants to know the different situations in which she can take time off and how much time off she gets.

• Hierarchy. Organizing from the bottom up or the top down—from smallest to largest, or most expensive to least—works well on its own or in combination with a category approach.

Use Plain Language

Many of us who have worked in HR for a long time are susceptible to a syndrome known as “The Curse of Knowledge.” Chip Heath and Dan Heath describe this syndrome in their book Made to Stick: “Once we know something, we find it hard to imagine what it was like not to know it. Our knowledge has ‘cursed’ us.”2 The result is that we write content that’s too technical, so it’s difficult for anyone who is not an expert to understand.

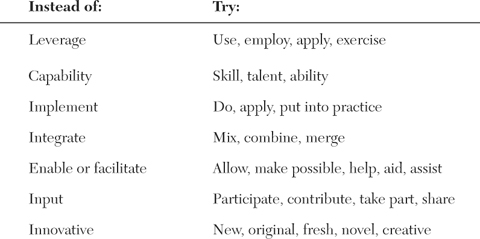

Luckily, you can cure yourself of this curse in several ways. The first is to stop using jargon that no one but you and your other subject matter experts find interesting. Second, you can get rid of any and all words and terms that are difficult to understand. For instance:

But you might protest that you must use specific HR terms because they’re the only way to accurately describe certain things, or because they’re legally required. If this is the case, you must not assume that the average (or even above-average) employee understands these terms. Instead, define the term—and, even better, provide a quick glossary.

A Good Test for Simple Language

How do you know if your language is simple enough? Check your readability. The average American reads at a 9th grade level, so some companies use that as a guide (as do publications such as Reader’s Digest).

But an HR communicator we admire recently convinced senior management that all employee communication at her company needs to be written at a 7th grade level, which happens to be the level of most marketing (including ads created by her company). Her research showed that the 7th grade level is easiest for employees to understand. As she tells it, “We’re not ‘dumbing down’ anything. We’re making information accessible to everyone.”

To check your readability using Microsoft Word, first open the Preferences menu and then the Spelling and Grammar section. Make sure that “Show readability statistics” is checked. Now, when you’re drafting or editing a Word document, go to the Tools menu and choose “Spelling and Grammar.” Run your document through the spelling and grammar checking process (always a good idea, anyway). At the end, a window will pop up that shows your Flesch-Kincaid grade level score. If it’s 12th grade or above, your writing is probably too complex.

How to Keep It Short and Simple

Here are some rules of thumb:

• Keep sentences at about 14 words.

• Limit paragraphs to three to four sentences.

• Create articles (in print or on the web) that run only 300 words or less.

• Use three to seven words in headlines.

Be Concrete

Here’s the first sentence of a bad job description that we suspect confused rather than attracted candidates:

We’re looking for a business/marketing expert who is a strategic and creative thinker with a natural ability to translate complex technical concepts into business results-oriented narratives that resonate with the organization, business, and industry.

This lead sentence is a lot of sound and fury, signifying nothing. It’s an overload of jargon, and it doesn’t begin to answer the basic question: What will the person in this job actually do? (By the way, this is just the beginning of the bad job description; you can see the whole horrible thing in Chapter 10, “Recruiting.”)

When confronted with poor information like this (which you often are), your best tactic is to ask a lot of questions. The answers will give you information you need to change the vague to the concrete.

To create a meaningful job description for the job just mentioned, you’d want to know who this person would report to, how many people he or she would supervise, what the main deliverables are, when they are due, what groups the person would work with, how much time he or she would spend on different activities, and so on.

Collect concrete, specific examples and stories, describe how the person in the job will spend most of his or her time, and note special skills or expertise that will be valued. You’ll have a job description that will attract qualified candidates.

Tell Me a Story

One of the best ways to make communication concrete is to tell personal stories. Like photos, they are worth a thousand words. If I can find one person with a story that will make my life easier, make me more productive, make me happier at work, that’s much more tangible than all the abstract terms you can muster.

We are all interested in personal stories because we realize, “Here’s someone just like me” or “Here’s someone I admire.”

In some HR communications, you can feature real employees telling real stories—and that will make your communications much more powerful. But employees may not want to talk about certain topics. You can still tell the story; just don’t use the person’s real name or details.

Checklist for Writing Simply

To make sure your message is perfectly clear, you’ll want to master “sailing the seven Cs.” When you’ve finished writing (or when you review someone else’s writing), ask yourself if your writing is

![]() Clear—Is it easy to understand?

Clear—Is it easy to understand?

![]() Concise—Is it as brief as it can be?

Concise—Is it as brief as it can be?

![]() Comprehensive—Does it include all the necessary topics?

Comprehensive—Does it include all the necessary topics?

![]() Complete—Does it include all the necessary details?

Complete—Does it include all the necessary details?

![]() Correct—Is the information accurate?

Correct—Is the information accurate?

![]() Credible—Does it add up?

Credible—Does it add up?

![]() Conversational—Does it sound like a real person talking?

Conversational—Does it sound like a real person talking?