4. Earnings and Corporate Announcements

“To be angry at the market because it unexpectedly or even illogically goes against you is like getting mad at your lungs because you have pneumonia.”

—Jesse Livermore

Many shocks that buffet individual stocks on a daily basis are precipitated by company-specific news or actions. The changes may be large or small, long lasting or short-lived. The impact might be limited to one company’s stock or spread to other stocks in the same industry or the market as a whole. These market shocks may arise from earnings or special dividend announcements, lawsuits, sales or new product announcements, executive suite changes, merger or acquisition announcements, and regulatory actions. A myriad of potential examples are created every trading day. This chapter focuses on several examples to illustrate how various types of company-specific news can induce sudden shocks in stock prices and assesses the trading implications.

Earnings

Earnings are central to the proper valuation of stocks. Earnings reports are a frequent source of large market shocks. The Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) Regulation Fair Disclosure requires U.S. corporations to disclose material nonpublic information to the public at one instant in time rather than selectively disseminating it to favored investors. In layman’s terms, it means important information has to be disclosed publicly and all at once, so that no investors can get a heads up on market-moving information. The fact that material nonpublic information cannot be selectively disclosed has thus increased the probability that financial reports might contain potentially market-moving information.

Earnings report release dates are scheduled far in advance. This allows traders to know when to expect potential market shocks induced by the release of earnings reports. It also facilitates traders getting a consensus estimate of earnings forecasts for stocks followed by analysts’ opinions and estimates. Earnings contain important information for every trader—often even for traders not trading the stock in question. For example, FedEx and UPS are seen by some observers as bellwethers for the U.S. and global economy.1

“Google shares intraday have fallen off a cliff right now,” Dominic Chu of Bloomberg News reported on October 18, 2012.2

That’s something no one holding a stock ever wants to hear—but midday October 18, 2012, Google investors and the market as a whole were in for a rude shock.

Due to an accidental release by R.R. Donnelley & Sons Co. (its filing agent), Google’s disappointing third-quarter earnings were revealed early. As the news was breaking, Dominic Chu had this to say:

“We’ve got an early release here from Google, third-quarter adjusted earnings per share...9 dollars and 3 cents...the analyst estimate, 10 dollars and 65 cents....”3

The stock declined more than 6.5%, but it had further to fall. Google stock plummeted 11% before trading was halted at Google’s request.4

Macquarie Group senior Internet analyst Benjamin Schachter said:

“When it first happened we thought maybe there was some sort of fraud involved or something askew, but it really turned out that someone had published the results early.”5

Not only did the –15.3% earnings per share miss shock the market, but the surprise and confusion of the inadvertent early release by R.R. Donnelley contributed to the near $80 dollar fall.6 In only eight minutes, Google stock fell 9% and $24 billion of shareholder value was wiped out.7 Price targets for Google shares were subsequently cut by at least seven brokerages.8

Aside from the confusion caused by the early release, one of the main reasons Google fell so precipitously was the fact that the “cost-per-click” Google receives from serving ads declined 15% from the prior year.9 This was attributed to Google’s inability to charge more for advertisements it places on mobile platforms, such as smart phones or tablets running Google’s own Android operating system.10 This was a huge blow to Google, a company whose very name has become synonymous with “search.”

Many saw Google as well-placed despite the bad news. eMarketer has estimated that Google has a 95.4% share of revenues in the mobile search ad market—a gargantuan share.11 Some cause for the loss was also attributed to Google’s recent acquisition of Motorola Mobility.12

Considering the speed of the Google drop—billions lost in less than 10 minutes—reacting to this shock would be difficult for many traders. Moreover, the surprise of the shock meant that most traders were unprepared for it. However, this move presented a couple of options for a trader willing to act quickly and take risks.

First, you might have profited from the rebound. The sheer size and speed of the initial fall, coupled with the fact it was partially built on confusion, supports the case for a modest correction upwards later in the day, which did occur. The stock closed down 8%—an improvement from its 11% intraday fall. As Forbes.com noted at 3.24 p.m. the day of the plunge in Google’s stock price:

“Shares in Google resumed trading at 3:20 PM, bouncing $695.00, still down 8% but popping nicely from its $676-low.”13

Second, it was a potential long-term buying opportunity. Although many analysts downgraded their view of the stock, their downgraded prices often continued at a premium to the post-crash price. Anthony DiClemente, an analyst at Barclays, put it this way:

“We believe dislocation in shares creates a buying opportunity, ... [and Google] can benefit from ecommerce tailwinds and moderation in CPC (cost per click) declines on easier (comparables).”14

According to Marketwatch.com, on October 23, 2012, five days after the crash, and after several downgrades, Google had an average analyst price target of $799.84, suggesting that many believed the crash to be a (large) bump in the road, but a bump in the road nonetheless.

Apple

Sometimes earnings announcements can have seemingly disproportionate effects on a stock. A small deviation from expectations can have a big impact on the stock price—up or down. Imagine for a moment that you were a short-term trader who had inside information about Apple stock. You also learned that Apple was about to beat its own revenue and earnings per share estimates. Putting aside the obvious illegality of trading on inside information, what would be the clear course of action?

The answer would appear to be: “Buy Apple stock.”

However, in some cases, this would be exactly the wrong course of action. On July 24, 2012, Apple released an earnings announcement for its fiscal third quarter ending June 30, 2012. The earnings announcement indicated fewer iPhones sold than expected and lower earnings per share than the Street expected even though reported earnings per share were greater than Apple led analysts to believe they would be. Martha White at Marketday on NBC reported:

“Apple...reported...earnings per share of $9.32 for the quarter...higher than Apple’s own guidance of...$8.68, while the Street had been expecting...$10.35....”15

Apple shares fell by 4.3% in response to this news:

“Apple, the world’s largest company by market value, fell to $574.97 at the close in New York.”16

Apple beat its own estimates, yet the stock fell by 4.3%. This reinforces the fact that the market consensus—not the consensus of a few players—is the consensus that matters. Understanding this consensus is critical. Traders who looked at Apple’s estimates would have seen higher-than-expected earnings. However, traders who understood that the market had already priced in earnings expectations higher than Apple’s own estimates would not have been surprised. The analysts’ consensus predicted even higher estimates than Apple’s. Even though Apple beat its own estimates, its share price fell by a little less than $3 a share by the close—and tumbled down by around $25 a share in aftermarket trading.

Facebook and Zynga

Sometimes the earnings of two companies can have a disproportionate result on each other, as was the case for early earnings reports for Facebook and Zynga.

This connection was a widely discussed industry view. CNET wrote an article on this phenomenon: “As Zynga falters, so does Facebook.”17 The Next Web claimed Zynga’s results “sets the stage” for Facebook’s earnings release the next day.18

Unfortunately, Zynga had extremely poor results. The article conjectured that going public might become more difficult for high tech firms if the Zynga-Facebook earnings report relationship continued after another poor earnings report by Zynga:

“Zynga just set fire to more than a third of its market value by missing expectations by a simply astounding margin.”19

In the first quarter of 2012, Zynga accounted for $159 million of Facebook’s $1.06 billion in revenue.20 This close relationship meant investors saw problems with Zynga as indicative of problems at Facebook. One could say that Facebook and Zynga weren’t exactly married, but they were in a serious relationship.

CNN Money noted that Facebook investors were:

“...more nervous about Facebook’s results...after...Zynga...reported earnings that missed forecasts ...Zynga’s stock plunged nearly 40% Thursday and Facebook fell more than 8%.”21

Facebook beat the estimates, just, with reported revenues of $1.18 billion, earnings per share of $0.12, and ad revenue of $922 million.22 These results were a 45% increase over the previous year.23

Yet Facebook’s stock price was down 8% intraday. But that’s not all. The next day Facebook opened at a new low and was down 14%.24

That’s because Facebook’s expenses reached $1.93 billion, close to a 300% increase when compared to the prior year. Moreover, Facebook’s revenue was up 32%, but that still wasn’t good enough for the Street because the growth was not as fast as in some previous quarters.25

Furthermore, The Guardian noted that:

“Mobile use has worried investors as Facebook has admitted it has yet found it hard to make money off those accounts.”26

The problem essentially centered on the fact that a majority of Facebook users were primarily accessing their accounts from mobile devices rather than personal computers.

Facebook’s momentum was on a downward track ever since the much-hyped IPO was beset with trading glitches and unsustainable valuation. Meeting analysts’ estimates might have proved Facebook was not a total basket case, but it did nothing to reverse the nagging sense that Facebook was overvalued. The failure of Zynga to meet expectations was another major contributing factor. Lingering worries about the near expiration of Facebook’s lockup periods, which would let insiders and early investors sell their shares of the company, probably contributed to the fall.

The rapidity at which the market crafts a new narrative was apparent at the next earnings report—when the exact opposite market reaction happened. Zynga, still important to Facebook’s bottom line, lost seven cents per share and fired 150 employees. This was a negative report, but in line with estimates. Zynga also announced a $200 million share buyback program.27

But this time, Zynga was up 14% in after-hours trading.

On Facebook’s side, expectations for Q3 earnings were similar to those for Q2. Expected results were revenues of $1.23 billion with earnings of 11 cents per share. Actual results were revenues of $1.26 billion with earnings of 12 cents per share.28 Just like Facebook’s Q2 results, this performance was slightly better than analysts’ estimates.

This time Facebook was up more than 11% in after-hours trading—and more than 20% higher the morning after the announcement.29, 30

On the surface, this result was puzzling. Facebook and Zynga both surged while reporting in Zynga’s case an expected loss and in Facebook’s case earnings only barely above expectations. Two factors are at play here: an oversold market ready for a rally and, for Facebook stock, an increase in mobile ads. A difference between the Q2 and Q3 results was the share of Facebook’s advertising taking place on mobile devices. Although only accounting for $10 million in the previous quarter, Q3 delivered around $150 million from mobile platforms.31

Analyst Brian Wieser at Pivotal Research Group said: “Mobile problem? What mobile problem?” Wieser said, “It’s nothing short of remarkable.”32

Considering that mobile was widely seen as Facebook’s weak spot this amounted to a gigantic change. Although total revenue changed slightly, mobile revenue saw a 15x surge. Business Insider estimated Facebook’s mobile ads were now worth $1 billion per year.33

David Ebersman, Facebook CFO said:

“We ended the third quarter with more than $4 million a day coming from Feed and about three-quarters of that coming from mobile Feed.”34

Although this reflected a significant improvement in Facebook’s business, the picture wasn’t rosy all around. On November 14, 2012, more than 1.2 billion shares of restricted Facebook stock would see their lockup period expire.35 It is possible this was already priced into the stock. Ironically, a surge in the price might make holders of the restricted stock more likely to sell off some of their holding in an upswing. Surprisingly enough, the day the lockup expired the stock was up 10.3%.36

One reason for Facebook’s rise from somewhat similar earnings results could just be attitude. Indeed, Adrianne Jeffries at The Verge noted that Mark Zuckerberg was trying much harder to please Wall Street this time around:

“Zuckerberg...seemed eager to please... [and] preempted investor skepticism by immediately addressing Wall Street’s pet gripes, namely Facebook’s mobile strategy and its close link with...Zynga.”37

Because Facebook had a relatively new business model, and Mark Zuckerberg, through preferred shares (and a voting rights agreement) had absolute power,38 it was not surprising that investors were leery of any seeming unprofessionalism on his part.39

Given his massive loss in wealth in addition to some calls for his resignation, he had every reason to work hard to erase the downward slide in the stock price.40 Considering Facebook had lost more than 50% of its value mere months after the IPO, the stock was arguably oversold.41 The surge in price of Zynga off mediocre results suggests that the market was ready for a rebound. Such a large surge in the price of an interrelated stock was a signal that Facebook was oversold and ready for a surge of its own. Smart traders should look to the performance of interrelated stocks as a guide for possible future results of linked stocks.

Sudden Drops

Sometimes an earnings report is the straw that breaks the camel’s back. In what Reuters whimsically called “Christmas for shorts,” Green Mountain Coffee Roasters (GMCR) lost almost two-fifths of its value on May 3, 2012:42

Green Mountain shares sank nearly 40% in early morning trading Thursday, dipping to about $30 after closing Wednesday at $49.52.43

Its earnings met estimates of 64 cents per share, but revenue missed expectations of $972 million, instead pulling in $885 million. It’s not only the “bottom line” (earnings) that matter to the market, but also the “top line” (revenues).

The company was at a loss to explain why expected revenue was not met. CNN Money noted:

“Executives...suspiciously trotted out the weather excuse, i.e. that an unseasonably mild winter meant fewer people drinking hot beverages like cocoa and cider.”44

GMCR, which had been under pressure—from among others, famous short seller David Einhorn—was a stock with a bull’s-eye on its back. A list of woes preceded this earnings report. An SEC investigation ongoing since 2010, pressure from other short sellers, and a record of years upon years of fantastic growth that—short of a new business model—was unsustainable.45

The timing of the shock was not predictable (short of having inside information about the earnings miss), but it was clear that GMCR was under a large amount of pressure.

The downtrend and possible crash in GMCR was, as some academic literature attests, predictable. For instance, Drake, Rees, and Swanson [2010] report evidence of a profitable trading strategy that goes short:

“...when the short interest signal strongly conflicts with the consensus analyst recommendation.”46

Some noted GMCR’s coupling of high short interest and analyst buy ratings:

“...9 out of 12 analysts had a buy rating...Only one rated [it] ...a “sell.” ...23% of stock was held short...”47

Does this mean a trader could have predicted the exact date of the fall? No. Does it mean a trader could have known GMCR would miss earnings? No. Does it mean a trader could have known GMCR had to fall 40%? No. However, it does mean traders had a preponderance of evidence on the side of shorting GMCR. No sure bets exist in trading, but the bet against GMCR was weighted on the side of the shorts. With all signals pointing downward, it was a lopsided bet.

New Products—Videogames

Shares of Take-Two Interactive spiked almost 8% on the release day of L.A. Noire,48 a videogame years in the making. With a known release date and such a long development cycle, why didn’t the market factor such a known quantity into Take-Two’s stock price?49

An article on Industrygamers.com quoted Sterne Agee analyst Arvind Bhatia, as saying:

“...the Street is expecting the title to sell 3 to 4 million units and...initial reviews...support this thinking....”50

The same article also noted that L.A. Noire was the number-one-selling videogame that week and had sold well on Amazon.com.51

This was a title with a lot of anticipation and hype. So why the sudden surge on the day of the game’s release?

It turns out some significant doubts existed within the gaming industry as to whether Take-Two could pull off such an ambitious game, one that departed from the successful formula of their money-printing classic, Grand Theft Auto series, and whose sharp design changes led one observer to anticipate a “backlash” from consumers.52

But did that backlash come to fruition? No, in fact, L.A. Noire was rated very highly. Evan Narcisse on Time Tech noted that the game had received:

“...an average score of 90 on Metacritic...[which] caused a jump in Take-Two’s stock price, which started yesterday at $15.93/share and ... [closed] at $16.90/share....”53

But could you have known that L.A. Noire exceeded the lofty expectations set by the games industry? If you aren’t a gamer, could you have traded this stock? The answer is a resounding “yes.” It is relatively common for early impressions of videogames to leak before release dates. In fact, some games have even been leaked through file-sharing sites before their release. This should not be misinterpreted as condoning the illegal downloading of game files but rather to point out that some information about the game has been released to a select audience (game enthusiasts) before the official release. This provides some traders with asymmetric information. In this case, however, no downloading was necessary. The Guardian released its L.A. Noire review on May 13, days before the May 17 release date. The game was given a perfect score. The review was taken down shortly after being posted online, but videogame enthusiasts copied the review and it was disseminated widely on several gamer websites.54, 55

The release of L.A. Noire is a case of information released early—great reviews of an important release—yet not being incorporated into the company’s stock price. This is partially an industry issue. It is doubtful that most traders were salivating to play this game, and many might not have known about it. However, traders who did their research about such an important release would have had literally days to put a position on Take-Two stock before the rally. Even traders who did not act in advance could have profited off the move. Take-Two stock did not begin the rally until around 1:30 p.m.56 You could have read the reviews on the day of the release, gotten lunch, and still had time to buy a position before the rally.

It turns out that this is not an isolated case. There is evidence that poor reviews of a single videogame can lead to massive changes in a company’s stock price.

An article, also in Time Tech, noted that shares of THQ fell more than 20% in one day after the much-anticipated game Homefront received “lukewarm” reviews.57 With more than 200,000 pre-orders—the most in THQ’s history—Homefront seemed primed for success. However, anticipation turned to disappointment when the reviews came in, considering that THQ’s CFO claimed the title would have to sell two million copies or more to break even.58

The importance of good reviews and good sales is amplified by the rest of his comments:

“Once you get past that you’re generating incremental operating margins as high as 60 percent.”59

Reviews are crucial to videogame companies because the companies have high fixed costs—the development of a game—with theoretically unlimited profit potential past the breakeven point. Bad reviews mean that what appeared to be a 60% margin, moneymaking monster could turn out to be a loser.

So what can we say about these examples? Well, it is clear that reviews are important to game purchasers. The Wall Street Journal noted that videogame review sites play an important role in the industry:

“...because the stakes are higher for consumers shelling out $50 to $60 for a new game than they are for someone buying...a $10 movie ticket.”60

Major game publishers such as Activision and Take-Two Interactive use the ratings of their games to help determine their employees’ bonus compensation. An Activision study discovered that every five percentage point ratings increase above 80% on the popular review site, Game Rankings, led to an approximate doubling of sales:

“Activision believes game scores, among other factors, can actually influence sales, not just reflect their quality.”61

But can you trade from these examples? Yes. Although the examples showed quick reactions to poor reviews—spikes or falls of 10% or 20%—sometimes reviews can set a trend of a stock for months, leaving ample opportunity for trading profits. Quality information is sometimes released early.

This idea is supported by the trials that faced Funcom after its much hyped game, Homefront.

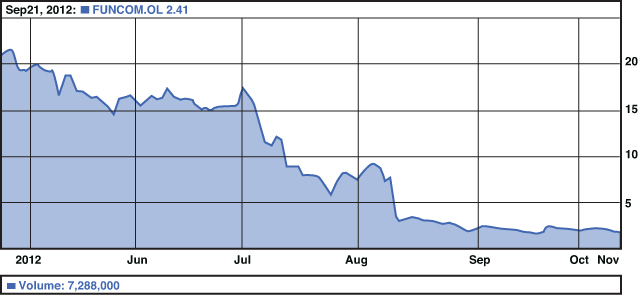

Not only can reviews lead to brief market shocks, they can also induce a long-term trend that is tradeable on for months. Funcom is the developer of a previously hyped MMO (Massively Multiplayer Online) game called The Secret World. Upon its release on July 3, Funcom stock fell slightly, with another small drop on July 4. It wasn’t until July 5 and 6 that the stock started to fall significantly—closing at $11.40 on July 6, a near 45% drop from its July 3 price.

Funcom issued an investor relations update on August 10, 2012. In it, Funcom directly placed the blame for its share price decline on poor reviews of The Secret World, reflected by its low average review score at MetaCritic and similar sites. It stated:

“A game like The Secret World...is normally dependent on positive press reviews to achieve successful initial sales, in addition...to other factors like word of mouth.”62

On August 10, the price again plummeted from the previous day’s closing of $7.83 to $3.75, yet it still had farther to fall. Save a few minor rallies, the stock continued to slide. By November 7, Funcom was trading at $1.50 per share, less than 10% of its price on the date of The Secret World’s release, as shown in Figure 4-1.

(Reprinted with permission from Yahoo! Inc. 2013 Yahoo! Inc. [YAHOO! and the YAHOO! logo are trademarks of Yahoo! Inc.])

Figure 4-1. The behavior of Funcom stock following the release of its MMO game, The Secret World, on July 3, 2012.

Although a fall of this scope seems unpredictable and irrational, Funcom is a relatively small company, far from the size of an EA (Electronic Arts) or Activision-Blizzard. Therefore, a poor reception for one game will have a much larger impact on the stock price than with a larger, more diversified game company.

So, how could you have traded on these shocks?

Could you have known about the game’s quality problems before July 3? A game enthusiast—or a trader with friends who are—should have. Customers who pre-ordered the game were able to start playing on June 29, days before the July 3 official release date.63 The stock had a mini-rally until July 2, the day before release—and the stock didn’t fall until July 3. Moreover, it didn’t fall hard until July 5 and July 6. Hardcore gamers—and traders devoted to their research—could have known about the game’s problems before it was released, yet it was not seriously reflected in the stock until several days after the release. Not only could you have tried the product before release (gaining legal advance information), the market didn’t reflect this information for several days. Moreover, you could have missed the initial fall and still made money on later drops in price.

These examples in the videogame industry reveal several important trading lessons. In some industries, market information is released early, but not fully incorporated into stock prices. In the case of L.A. Noire, information on positive reviews was available for days. On the day of the release, there were hours to make the trade. This is likely because many traders might not be able to discern videogame appeal (and hence demand) as much as, say, a teenager. Because those teenagers are unlikely to also be traders, you have a classic case of important information not being incorporated into the stock price. But sometimes information can start a long-term trend. In Funcom’s case, you could have made money on both the initial reaction to poor reviews and the long-term trend created by poor sales and reduced expectations for the company as a whole.

Mergers and Acquisitions

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are another important source of market shocks. Deals can be friendly or hostile. The largest shocks usually occur in the target company’s stock price. The announcement of a bid causes the price of the target firm to rise significantly. The stock price of the acquiring firm usually falls slightly but sometimes also rises. Sometimes the stock price of the target rises by more than what the acquiring firm has offered to pay for it. This happens when the market anticipates other bidders entering the market or that the acquiring firm will be forced to pay more. Occasionally, an acquirer might even offer less than the market price for a stock.

Anatomy of a Deal: Bank of America and Countrywide Financial

It is easy to forget that the worldwide financial crisis of 2007–2009 originated as a subprime mortgage crisis in the U.S., before morphing into a global banking crisis and then into a global credit crisis. It was widely thought that the subprime mortgage crisis could be contained. Indeed, the stock market did not reach its peak until October 9, 2007 in the U.S., and October 16, 2007 in China.

The dream of building a nationwide full-service bank has been a seductive one for many U.S. bank CEOs. So when the subprime mortgage crisis started to exert pressure on some high-profile subprime lenders in mid-2007, Bank of America seized the opportunity.

On August 22, 2007, Bank of America (BAC) made a strategic investment in Countrywide Financial Corporation (CFC)—a major subprime mortgage lender—by purchasing $2 billion of 7.25% convertible preferred stock in CFC. The preferred stock was convertible at $18 per share. This allowed BAC to acquire around 111.111 million shares of CFC common stock or about 16% of CFC.64

At the time of the deal, CFC stock was trading at $21.82 per share. Yes, that is right, Bank of America agreed to buy $2 billion of preferred stock of CFC with an option to buy CFC common stock at $18 per share when the stock was trading at $21.82. Simply stated, the stock was already $3.82 in-the-money for each share. That meant it wasn’t really a $2 billion investment by Bank of America—it was at most a $1.576 billion investment because the option to convert if exercised immediately was worth $424 million (that is, $3.82 × 111.11 million shares).

This was a great deal for Bank of America stockholders. How did the price of CFC common stock react to news of the deal? It rose $4.54 per share or 21%. This meant that it was an even better deal for Bank of America because the new minimum value of the option to convert was worth at least $928.89 million.

Why did CFC agree to the deal? Most likely, Bank of America’s strategic investment in CFC was interpreted as meaning that CFC now had the support of a deep-pocketed investor. How did Bank of America arrive at the value for the preferred stock deal? Most likely, Bank of America was given full access to information about Country-wide’s portfolio of subprime mortgages in order to estimate the “true” value of the portfolio. The deal gave Bank of America the opportunity to acquire a significant stake in a business it wanted to expand into at a bargain basement price. The strategic investment in CFC in August 2007 looked like a very smart move by Bank of America at the time.

Although the subprime crisis continued to worsen, another opportunity to buy into the subprime mortgage business soon presented itself. On January 11, 2008, Bank of America agreed to acquire the rest of Countrywide Financial Corporation for about $4 billion in stock.65 A Bank of America press release noted that the acquisition would make the bank:

“...the nation’s largest mortgage lender and loan servicer. This is an important advancement in the company’s desire to help customers...meet all of their financial needs.”66

The deal was expected to close in the third quarter of 2008. The proposed terms of the all-stock deal were interesting. Bank of America agreed to pay 0.1822 shares of BAC for one share of CFC. Given where Bank of America was trading at the time of the announcement, this was tantamount to an acquisition price of $7.16 per share or about $4 billion in total.67 However, the acquisition price represented a $.59 discount to the closing price of $7.75 on January 10, 2008. Bank of America had bought a major stake in CFC at a discount to the market in August 2007 and CFC’s stock price rose.

So what was the market’s reaction to news of the deal? CFC closed at $7.75 per share on January 10, 2008 and at $6.33 per share on January 11, 2008 after the announcement or down 18%. BAC closed at $38.50 per share on January 11, 2008. This meant that the implied value per share of BAC’s bid for CFC on January 11 was $7.01 per share (that is, $38.50 × .1822).

The all-stock deal meant that CFC would slide in price as BAC fell or if investors feared the deal would not get done. CFC continued to fall. CFC closed at $6.09 on January 14, 2008 and $5.81 on January 15, 2008. A gap soon emerged between the implied value of CFC and the effective agreed price (that is, 0.1822 × BAC’s stock price). CFC fell another 9.49% to close at $4.96 per share on Friday, January 18, 2008. BAC closed at $35.97 per share that Friday. The implied value per share of BAC’s bid for CFC at the close on Friday, January 18, 2008 was 59 cents higher or $6.55 (.1822 × $35.97). Considering that CFC was supposed to be worth around 18% of BAC’s share price—but was actually trading for less on the market—meant that investors feared the deal would not go through.

BAC traded at $34.00 per share the same morning as it missed its fourth-quarter earnings estimate by 16 cents per share due to a write-off of $5.3 billion mortgage-backed securities. At one point, CFC fell $.44 to $4.52 per share in pre-opening trading on January 24, 2008. This was far below the implied value per share of CFC of $6.19 (that is, 0.1822 × $34.00) per share.

To be sure, the price of CFC was influenced by other factors in the market. However, the immediate negative reaction in CFC’s stock price suggests that the market both had a dim view of the wisdom of the proposed acquisition of CFC by BAC and felt the deal was unlikely to happen.

The Federal Reserve approved the acquisition of CFC by BAC on June 8, 2008. The deal closed later in 2008.

Quaker Buys Snapple

In what was called “one of the worst flops in corporate-merger history,”68 on November 3, 1994, Quaker announced an agreement to buy Snapple for $1.7 billion. It invested millions more in its operations. Twenty-seven months later, Quaker sold Snapple to Triarc Cos. for $300 million.

The deal was an attempt to combine:

“...the marketing muscle and growth potential of two of the great brands in an increasingly health-conscious America: Gatorade in sports drinks and Snapple in ice teas and juice drinks.”69

On the day the acquisition was announced, the market reaction was swift—and negative.

“Quaker’s stock sank $7.375, or almost 10 percent, to $67.125 a share on the New York Stock Exchange.”70

With such a dramatic 10% fall, the market already foresaw some of the wealth destruction to come.

Ironically, some market participants believed the deal to substantially undervalue Snapple. The New York Times quotes one trader referring to the deal as a “take-under.” In fact, the same day the deal was announced, angry shareholders filed 13 lawsuits accusing Snapple of selling out for too little.

Despite the lawsuits, Quaker acquired Snapple for $1.7 billion in cash.71 A disastrous failure, Quaker only held on to the business for a little more than two years, losing an estimated $1.6 million per day it owned Snapple. The reasons for this were myriad, with increased competition, reduced demand, and an unfamiliar business model all contributing to the abject failure of the deal.

When the company was sold to Triarc, Quaker’s total losses on Snapple were estimated to be around $2 billion. Despite this, investors were pleased to wash their hands of the matter even though Snapple was sold for substantially less than expected:

“Investors responded enthusiastically.... The shares of Quaker...jumped $2 today...before settling back to end at $37.75, up 25 cents. Triarc’s shares advanced $1.625, to $17.375.”72

Despite the massive loss of shareholder wealth, investors were happy to put the period behind them, and the stock rose in response. The Snapple deal shows that the market is a better guide to the true value of a deal—it fell 10% on announcement—than the platitudes given by a CEO. It also shows that although acknowledgement of steep losses is painful, putting a company on the right course for the future—in this case by getting rid of dead weight—has a positive impact on shares.

If you are a long-term investor, you should be aware that “researchers estimate [the] range for failure [for mergers] is between 50% and 80%.”73 The editor of Mergers & Acquisitions: The Dealmakers Journal, Martin Sikora argues: “The accepted data say that most mergers and acquisitions don’t work out.”74

Merrill Buys FRC

On Monday, January 29, 2007, Merrill Lynch announced an agreement to buy San Francisco–based First Republic Bank (FRC) at $55 at per share or approximately $1.8 billion. First Republic bank shares closed up $15.33 or 40% to $53.63 per share on the news. The January 30, 2007 issue of the Wall Street Journal reported that:

“Merrill is paying a handsome price... [The] offer represents a multiple of 24 times the target’s projected 2007 earnings... [and] twice Merrill’s own valuation.”75

The price of Merrill Lynch stock closed down $2.14 or 2.3% to $92.39 after the deal was announced. Moreover, the decline occurred on a day where the overall market—as measured by the S&P 500 index—fell 0.1%, and there was no other company-specific news for Merrill. The First Republic Bank acquisition was it. Given that 883.97 million shares of Merrill Lynch were outstanding at the time of the announcement, the $2.14 stock price decline meant that the market capitalization of Merrill fell by about the price Merrill Lynch paid for First Republic Bank. Simply stated, this was tantamount to Merrill spending $1.8 billion and getting nothing in return.

This is also a case where the positive shock to First Republic Bank’s stock price was large (up 40%), whereas the negative shock to Merrill’s stock price was small in percentage terms. However, this does not change the fact that the deal cost Merrill shareholders dearly, about $1.8 billion. It is clear that the market believed FRC was getting the better deal. FRC’s price was up 40%, reflecting what Merrill was going to pay FRC shareholders, while Merrill’s stock was priced as if the deal were worthless.

Deals That Fail

Not every M&A deal that gets done succeeds in creating value for shareholders of the acquiring firm as the Quaker-Snapple and Merrill-FRC deals demonstrate. Not every proposed M&A deal gets done. What happens to the stock prices of companies involved in deals that fail? You would expect the stock price of the target to fall because acquiring firms typically overpay. The stock price of the acquiring company often rises in relief that a bad deal failed.

Sometimes being left at the altar can be very beneficial. T-Mobile collected a $6 billion termination payment when AT&T withdrew its bid for the mobile carrier on December 19, 2011 after it became clear that it would not clear antitrust objections. The termination fee consisted of $3 billion in cash plus rights to wireless spectrum (for mobile phone use) with a market value of around $3 billion according to the New York Times.76

Changes at the Top

The expression “cutting the head off the snake” has been used in many contexts to signify vanquishing something that is perceived to be evil and destructive. In the case of poor performing CEOs, will “cutting off the heads” of poorly run corporations help shareholders? Conversely, will the surprise departure of well-performing CEOs of well-run corporations hurt shareholders? Changes in the executive suite matter to investors.

RIMM Shot

On January 22, 2012, Jim Balsille and Mike Lazaridis, co-CEOs of Research in Motion (RIMM)—the company now known as Blackberry (BBRY)—quit their positions as co-CEOs. Their departures should have brought cheer to RIMM investors. They had been the target of criticism for years, judged too slow to adapt to a changing mobile marketplace. An article on CBS MoneyWatch noted that RIMM had “destroyed a great brand” and had lost “$70 billion in shareholder value from its peak” while “investors openly call for a change in leadership.”77 The article ended with incredulity on just how poorly RIMM performed by sourly suggesting that performance that bad seems like it had to have been “part of a plan.”78

Another source noted that during recent years RIMM:

“...saw intense competition, declining sales, a failed tablet debut, and a long services outage...”79

Public relations were also a problem for RIMM, as Lazaridis had even gone so far as to walk off a BBC interview, which he believed to be unfair.80

Although investors were optimistic a new CEO would come and turn the company around, the market did not get what it was looking for. Thorsten Heins, a company insider, was appointed as new CEO of RIMM. The stock fell 8.5% by the close. One analyst called the change “necessary but not sufficient.”81 The same analyst noted that the appointment of Heins meant “...sale of the firm is unlikely for now.”82 This presumably contributed to the fall in price.

With no radical change in corporate strategy in the offing when many investors believed radical change was needed, replacing an ineffective CEO meant nothing, especially considering the replacement was a loyal company insider. News that appeared to be positive did nothing for RIMM stock.

Best Buy

Best Buy, the electronics retailer, had been under pressure for years. In 2006, operating income per square foot stood at $50.61.83 By 2001, that number had fallen to $18.52.84 This stands in stark contrast to the $1,100 per square foot in operating income Apple stores enjoyed.85 It also underscores the difficulty of competing with Amazon, which does not operate its own stores and offers lower prices. The resignation of Brian Dunn at Best Buy initially sent shares rising.86 Yet, that was short-lived and later became a selloff as shares finished the day down 5.9%.87 This might be due to the fact that no permanent replacement was named.

The chief equities analyst at NBG Productions, Brian Sozzi, summed up the market’s reaction:

“It’s good news that he’s gone...But this adds another layer of uncertainty.”88

The replacement of Dunn at Best Buy was initially seen as a good move, thus the stock rose. But soon, reality kicked in. Mr. Dunn was replaced due to an investigation into “personal conduct”—not over worries about his performance at Best Buy. Furthermore, as no permanent replacement was offered by the company, uncertainty increased. Instead of charting a hoped-for turnaround for Best Buy, this move led to confusion—and the market reflected that sentiment.

Wellpoint

Sometimes the removal of a CEO with no clear replacement can result in solid gains. This was the case for Wellpoint, the United States’ second-largest health insurer, when CEO Angela Braly resigned late August 28, 2012. Shares were up 5% in premarket trading and finished up 7.7% on August 29.89, 90 In this case, Braly had been hounded by criticism. Not only were earnings disappointing, there was even a dustup with President Obama

“...in 2010 for trying to raise rates by up to 39% in California. The national outrage that ensued helped Obama win approval for his healthcare overhaul in Congress.”91

Investor ire was a large component of her resignation:

“A person familiar with the board’s thinking said the move came because of ‘a firestorm from the investors....’”92

Some consumer advocates were also disappointed with her leadership.93 The frustration of several public battles was, presumably, an annoying distraction from the task of completing several acquisitions. Considering the groundswell of investor displeasure at the CEO, it was no surprise to see the stock rise 7.7% even without the announcement of a permanent replacement.

Regulatory Actions and Lawsuits

In terms of regulatory actions, one of the biggest trading catalysts can be approval or rejection of medicines. Blockbuster medicines have the potential to bring in billions of dollars in profits. A rejected medicine can mean millions of dollars of development over many years can suddenly become a sunk cost.

One extraordinary example was the 78% rise of Vivus (VVUS) when the company’s new weight loss pill Qnexa won the backing of an important regulatory panel.94 This recommendation did not mean instant approval by the FDA, although it boded extremely well for such approval.

Bloomberg News described the drug’s extreme potential if it were to become another blockbuster drug like Lipitor:

“Lipitor...is a cholesterol pill that had $10.7 billion in sales in 2010 before losing patent protection last year.”95

Antitrust regulations mean that some mergers require more than the agreement of the two parties. Justice Department approval is also needed. The decision can act as a market shock. For example, on March 24, 2008, the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Justice Department approved the proposed acquisition of XM Satellite Radio by archrival Sirius Satellite Radio in a $4.38 billion “merger of equals” deal. The approval was uncertain because the two firms were the only firms in the U.S. satellite radio market. The fear was that a merger of the two could lead to higher prices for consumers. A failure to approve a merger might lead to both firms going under. The decision to approve was justified on the grounds that the relevant market was larger than satellite radio alone. There were other competitors in other media. CNNMoney reported that XM Satellite Radio closed up 15.5% and Sirius closed up 8.6% after the announcement.96

Court decisions can also result in market shocks. One common reason for litigation is patent infringement claims. However, lawsuits can arise for any number of reasons.

Rambus Inc. has been a frequent litigant.97 It has tasted both victory and defeat in its litigation over the years. The failure of a lawsuit brought by Rambus Inc. against Micron Technology and Hynix Semiconductor Inc. that claimed the two firms attempted to fix chip prices led to a massive drop in Rambus’ stock price on November 16, 2011. Rambus’ shares closed down over 60 percent and had been down about 80% at one point during the trading day.98 Not surprisingly, the stock prices of Micron Technology and Hynix Semiconductor rose in response to the court decision.

Trading Lessons

When it comes to earnings announcements, expectations are key. When the market was negative on Facebook, barely surpassing earnings expectations led to a fall in the price. The next quarter it also barely surpassed earnings expectations—yet the stock soared. This is partially due to improved mobile numbers, but also largely due to a new market narrative that Facebook was probably oversold. Zynga stock experienced this same phenomenon, rising on mediocre news.

In cases of a fundamentally good business with a CEO or unit that isn’t seen as dragging down the whole company—as shown in the Wellpoint and Snapple examples—merely stopping the bleeding and starting over again can lead to rallies in the share price.

In cases such as Brian Dunn’s departure at Best Buy, the market initially rallied on the news he was gone, but with no clear replacement or plan to turn around the company, the stock quickly fell again. The same thing (minus the rally) happened with RIMM stock. The company has a fundamentally flawed business model, and making an insider CEO was not enough to change the narrative. In similar situations investors can expect similar market reactions.

Another important lesson is that in certain industries, such as the videogame industry, information that has a large impact on stock prices (in this case reviews) is often available early but incorporated into the price later. This gives even slow-moving traders a chance to profit on information, which is incorporated into the market slowly. Moreover, as detailed in the FunCom example, an important piece of news can have ramifications for months, sometimes leaving traders who missed the initial reaction ample time to profit on the aftershocks.

Company-specific news remains an important driver of stock prices and market shocks. In many cases, traders might be forced to respond to unscheduled news. The trades you can place in such situations are more limited than when news events are scheduled. Perhaps surprisingly, sometimes the information the market reacts to might be publicly available and “tradeable” before it becomes “news.” Sometimes the price action in one stock will spill over to others.

Another lesson that emerges is that, despite having valuation experts on staff, both Merrill when it acquired First Republic Bank and Bank of America when it acquired Countrywide Financial paid too much for the targets. Often, even the experts have trouble predicting the success or failure of a merger. This was also evidenced by the number of lawsuits filed due to the belief Snapple was being sold at discount.

Earnings are an example of a scheduled shock you can prepare for. Use these earnings’ report opportunities to set a position based on a trading thesis—or to avoid volatility you aren’t prepared for.

Endnotes

1. Weisenthal, J., “The Ultimate Economic Bellwether Reports Earnings Wednesday—Here’s What to Expect,” Business Insider, June 21, 2011. http://www.businessinsider.com/fedex-earnings-preview-2011-6.

2. Chu, D., “Lunch Money,” Bloomberg News, October 18, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/video/google-q3-eps-of-9-03-misses-10-65-estimate-UH~c6ajuQkWRU8M9V5egdw.html.

3. Ibid.

4. Sachdev, A., “Glitch on Google’s Earnings Report Under Investigation,” Chicago Tribune, October 19, 2012. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2012-10-19/business/ct-biz-1019-misstep-google--20121019_1_google-stock-google-ceo-larry-page-google-earnings-report.

5. CBS News, “Behind Google’s Surprise Earnings Report,” October 19, 2012. http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-505223_162-57535787/behind-googles-surprise-earnings-report/.

6. Wismer, D., “‘Larry, Puh-Leeze Insert Quote Here’ (Google’s Earnings Snafu and Other Quotes Of The Week),” Forbes.com, October 21, 2012. http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidwismer/2012/10/21/larry-puh-leeze-insert-quote-here-googles-earnings-snafu-and-other-quotes-of-the-week/.

7. CBS News, “Behind Google’s Surprise Earnings Report,” October 19, 2012. http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-505223_162-57535787/behind-googles-surprise-earnings-report/.

8. Reuters, “Google’s Facebook Problem: Monetizing Mobile,” The Fiscal Times, October 19, 2012. http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/Articles/2012/10/19/Googles-Facebook-Problem-Monetizing-Mobile.aspx#page1.

9. Wohlsen, M., “Google’s Woes Show Mobile Isn’t Just a Facebook Problem,” Wired.com, October 19, 2012. http://www.wired.com/business/2012/10/google-mobile-woes/.

10. Martin, S., “Google’s Earnings Clipped by Mobile,” USAToday.com, October 18, 2012. http://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2012/10/18/google-earnings/1641721/.

11. Sepe, V., “eMarketer: Twitter Tops Facebook in US Mobile Advertising Revenue,” in Fredricksen, C., “Posts Tagged ‘Google,’” eMarketer.com, September 5, 2012. http://www.emarketer.com/newsroom/index.php/tag/google/.

12. Bloomberg News, “Google Struggles to Boost Profit as Advertising Goes Mobile,” Newsday. October 22, 2012. http://newyork.newsday.com/business/technology/google-struggles-to-boost-profit-as-advertising-goes-mobile-1.4139560.

13. Fontevecchiha, A., “Google’s Third Quarter Earnings Released Early Big Miss on Profit,” Forbes.com. October 18, 2012. http://www.forbes.com/sites/afontevecchia/2012/10/18/googles-third-quarter-earnings-released-early-big-miss-on-profit/.

14. Reuters, “Google’s Facebook Problem: Monetizing Mobile,” The Fiscal Times, October 19, 2012. http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/Articles/2012/10/19/Googles-Facebook-Problem-Monetizing-Mobile.aspx#page1 and http://www.thefiscaltimes.com/Articles/2012/10/19/Googles-Facebook-Problem-Monetizing-Mobile.aspx#page1.

15. White, M.C., “As fans wait for iPhone 5, Apple misses earnings target,” July 24, 2012. NBC. http://marketday.nbcnews.com/_news/2012/07/24/12932507-as-fans-wait-for-iphone-5-apple-misses-earnings-target?lite.

16. Satariano, A., “Apple Stock Drops on Missed Estimates after IPhone Lull,” July 25, 2012. Bloomberg News. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-07-25/apple-declines-after-results-miss-estimates-on-iphone-sales-lull.html.

17. Tam, D., “As Zynga Falters, So Does Facebook,” CNET. October 23, 2012.

18. Wilhem, A., “Zynga misses: Q2 revenues of $332 million and non-GAAP earnings per share of $0.01 fall short of expectations.” The Next Web. July 25, 2012. http://thenextweb.com/insider/2012/07/25/zynga-reports-q2-revenues-of-332-million-earnings-per-share-of-0-01/.

19. Ibid.

20. Morris, C., “Zynga is One of Facebook’s Most Important Friends,” CNBC. May 16, 2012. http://marketday.nbcnews.com/_news/2012/05/16/11719029-zynga-is-one-of-facebooks-most-important-friends?lite.

21. Farrell, M., Facebook Earnings: Good, But Not Good Enough,” CNNMoney. July 27, 2012. http://money.cnn.com/2012/07/26/technology/facebook-earnings/index.htm.

22. Wilhelm, A., “Facebook’s Second Quarter Financials: Revenue of $1.18 billion, Earnings Per Share of $0.12,” The Next Web. July 26, 2012. http://thenextweb.com/facebook/2012/07/26/facebooks-second-quarter-financials-revenue-of-1-18-billion-earnings-per-share-of-0-12/.

23. Robles, P., “Facebook’s Q2 Earnings Report: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly,” eConsultancy. July 27, 2012. http://econsultancy.com/us/blog/10432-facebook-s-q2-earnings-report-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly.

24. Rodriguez, S., “Facebook Stock Opens at New Low a Day After First Earnings Report,” The LA Times. July 27, 2012. http://articles.latimes.com/2012/jul/27/business/la-fi-tn-facebook-stock-low-20120727.

25. Ibid.

26. Rushe, D., “Facebook shares fall after social network posts modest results.” The Guardian. July 26, 2012. http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2012/jul/26/facebook-shares-modest-results.

27. Thomas, O., “Zynga reports Third-Quarter Earnings.” Business Insider. October 24, 2012. http://www.businessinsider.com/zynga-earnings-2012-10.

28. Jeffries, A., “Facebook beats revenue expectations again, slightly.” The Verge. October 23, 2012. http://www.theverge.com/2012/10/23/3540086/facebook-earnings-q3-2012.

29. Jeffries, A., “Facebook stock soars on positive numbers and aggressive spin from execs.” The Verge. October 23, 2012. http://www.theverge.com/2012/10/23/3545104/facebook-stock-soars-earnings-call-q3-2012.

30. Egan M., “Facebook Rips 20% Higher on Mobile Progress.” Fox Business. October 24, 2012. http://www.foxbusiness.com/technology/2012/10/24/facebook-rips-20-higher-on-mobile-progress/.

31. Womack, B., “Facebook Shares Soar After Beating Estimates on Mobile.” Bloomberg. October 24, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-10-24/facebook-shares-soar-after-beating-estimates-on-mobile-gains.html.

32. Ibid.

33. Carlson, N., “From $0 to $1 Billion in Two Quarters—Facebook’s Mobile Ad Business Is Suddenly Huge.” Business Insider. October 23, 2012. http://www.businessinsider.com/starting-from-0-facebook-has-created-a-1-billion-mobile-ad-business-in-just-two-quarters-2012-10.

34. Ibid.

35. Isaac, M., “Facebook Stock Jumps, But Here Comes a Mountain of Lock-Up Shares.” All Things D. October 24, 2012. http://allthingsd.com/20121024/facebook-stock-soars-but-here-come-millions-of-lock-up-shares/.

36. Dillet, R., “Facebook Stock Price Up 10.3 Percent on the Day as Biggest Lockup Expires, Irrational Changes Are Over.” TechCrunch. November 14, 2012. http://techcrunch.com/2012/11/14/facebook-biggest-lockup-expiration/.

37. Jeffries, A., “Facebook stock soars on positive numbers and aggressive spin from execs,” The Verge. October 23, 2012, Op. Cit. http://www.theverge.com/2012/10/23/3545104/facebook-stock-soars-earnings-call-q3-2012.

38. Barusch, R., “At Facebook, Governance = Zuckerberg,” Wall Street Journal. February 1, 2012. http://blogs.wsj.com/deals/2012/02/01/at-facebook-governance-zuckerberg/.

39. Guynn, J., “Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg Won’t Sell Shares for One Year,” Los Angeles Times, September 4, 2012. http://articles.latimes.com/2012/sep/04/business/la-fi-facebook-shares-20120905.

40. “He’s in over his hoodie: Experts call for inexperienced Zuckerberg to step down as Facebook’s CEO as stock price continues to plummet.” The Daily Mail. August 20, 2012. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2190682/Hes-hoodie-Experts-inexperienced-Zuckerberg-step-Facebooks-CEO-stock-price-continues-plummet.html.

41. Robertson, A., “Facebook Stock Hits New Low of Less than $20,” The Verge. August 2, 2012. http://www.theverge.com/2012/8/2/3215553/facebook-stock-price-20-dollars.

42. Dalal, M., and B. Dorfman, “Green Mountain Plunges in Christmas for Shorts.” Reuters. May 3, 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/05/03/us-greenmountaincoffee-idUSBRE84217L20120503.

43. O’Toole, J., “Green Mountain Shares Sink 40% on Weak Outlook,” CNN Money. May 2, 2012. http://money.cnn.com/2012/05/02/markets/green-mountain/index.htm?iid=EL.

44. La Monica, P.R., “The Biggest Short: Green Mountain Bears Rejoice,” CNN Money. May 3, 2012. http://money.cnn.com/2012/05/03/markets/thebuzz/index.htm.

45. Dalal, M. and B. Dorfman, “Green Mountain Plunges in Christmas for Shorts,” Reuters. May 3, 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/05/03/us-greenmountaincoffee-idUSBRE84217L20120503.

46. Drake, M. S., L.L. Rees, and E.P. Swanson, “Should Investors Follow the Prophets or the Bears? Evidence on the Use of Public Information by Analysts and Short Sellers,” The Accounting Review, Vol. 86, No. 1, 2011.

47. Arold, M., “Green Mountain Coffee: Useless Analysts.” MichaelArold.com. May 3, 2012. http://www.michaelarold.com/2012/05/green-mountain-coffee-useless-analysts.html.

48. Williams, M.H. “L.A. Noire Raises Take-Two Shares to New Heights.” IndustryGamers May 18, 2011. http://www.industrygamers.com/news/la-noire-raises-take-two-shares-to-new-heights/.

49. Ibid.

50. Brightman, J., “L.A. Noire Has ‘Potential’ for 4 Million Sales.” IndustryGamers. May 17, 2011. http://www.industrygamers.com/news/la-noire-has-potential-for-4-million-sales/.

51. Ibid.

52. Narcisse, E., “No. 1 with a Bullet: ‘L.A. Noire’ Lifts Parent Company’s Stock Price.” Time Techland. May 18, 2011. http://techland.time.com/2011/05/18/no-1-with-a-bullet-l-a-noire-lifts-parent-companys-stock-price/.

53. Ibid.

54. “L.A. Noire receives its first review.” May 13, 2011. LA-Noire.Net Forum. http://www.la-noire.net/forums/thread-930.html.

55. “Guardian UK Newspaper Broke Embargo! Review here!” Xbox Forums. May 15, 2011. http://forums.xbox.com/xbox_forums/xbox_360_games/l_o/lanoire/f/371/t/2020.aspx.

56. “TTWO Shares Spike 7.75%—What Game Releases to Look Out for Next,” Analyst Weekly. May 18, 2011. http://analystweekly.wordpress.com/2011/05/18/ttwo-shares-spike-7-75-what-game-releases-to-look-out-for-next/.

57. Narcisse, E., “Did Review Scores for ‘Homefront’ Firebomb THQ’s Stock Price?” Time Techland. March 16, 2011. http://techland.time.com/2011/03/16/did-review-scores-for-homefront-firebomb-thqs-stock-price/.

58. Brightman, J., “Homefront Needs to Sell 2 Million to Break Even; Industry Shooting Itself in Foot,” IndustryGamers. March 10, 2011. http://www.industrygamers.com/news/homefront-needs-to-sell-2-million-to-break-even-industry-shooting-itself-in-foot/.

59. Narcisse, E., “Did Review Scores for ‘Homefront’ Firebomb THQ’s Stock Price?” Time.com. http://techland.time.com/2011/03/16/did-review-scores-for-homefront-firebomb-thqs-stock-price/.

60. Wingfield, N., “High Scores Matter To Game Makers, Too,” Wall Street Journal. September 20, 2007. http://online.wsj.com/public/article/SB119024844874433247-EnpxM1F6fI9YZDofC7VnyPzVrGQ_20070920.html?mod=todays_free_feature.

61. Ibid.

62. “The Secret World—Update.” Funcom.com. August 10, 2012. http://www.funcom.com/investors/the_secret_world_update http://www.funcom.com/investors/the_secret_world_update.

63. McCall, D., “The Secret World Early Access Starts Today.” The Inquisitr. June 29, 2012. http://www.inquisitr.com/266668/the-secret-world-early-access-starts-today/.

64. “Bank of America Makes Investment in Countrywide Financial Corp,” Bank of America press release, August 22, 2007. http://newsroom.bankofamerica.com/press-release/corporate-and-financial-news/bank-america-makes-investment-countrywide-financial.

65. “Bank of America Agrees to Purchase Countrywide Financial Corp,” Bank of America press release, January 11, 2008. http://newsroom.bankofamerica.com/press-release/corporate-and-financial-news/bank-america-agrees-purchase-countrywide-financial-corp.

66. Ibid.

67. More details on the proposed transaction are available at the SEC website using the Edgar information retrieval system. http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/25191/000090342308000052/bofa-425_0111.htm.

68. Peltz, J.F., “Quaker-Snapple: $1.4 Billion Is Down the Drain,” L.A. Times. March 28, 1997. http://articles.latimes.com/1997-03-28/business/fi-42931_1_quaker-bought-snapple.

69. Collins, G., “COMPANY REPORTS; Quaker Oats to Acquire Snapple,” New York Times. November 3, 1994. http://www.nytimes.com/1994/11/03/business/company-reports-quaker-oats-to-acquire-snapple.html.

70. Ibid.

71. Peltz, J.F., “Quaker-Snapple: $1.4 Billion Is Down the Drain,” LA Times. March 28, 1997. http://articles.latimes.com/1997-03-28/business/fi-42931_1_quaker-bought-snapple.

72. Feder, B.J., “Quaker to Sell Snapple for $300 Million.” New York Times. March 28. 1997. http://www.nytimes.com/1997/03/28/business/quaker-to-sell-snapple-for-300-million.html.

73. “Why Do So Many Mergers Fail?” Knowledge@Wharton. March 30, 2005. http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=1137.

74. Ibid.

75. Cox, R., L. Silva, and D. Cass, “Private Equity’s Bad Omen,” Wall Street Journal, January 30, 2007. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB117011508155791736.html.

76. De La, Merced, M.J., “T-Mobile and AT&T: What’s $2 Billion Among Friends?” New York Times, December 20, 2011. http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2011/12/20/att-and-t-mobile-whats-2-billion-among-friends/.

77. Tobak, S., “Blackberry—How RIM destroyed a great brand,” MoneyWatch. December 19, 2011. http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-505125_162-57344715/blackberry-how-rim-destroyed-a-great-brand/.

78. Ibid.

79. Ribeiro, J., “RIM co-CEO’s resign, new CEO to stay the course,” Infoworld. January 22, 2012. http://www.infoworld.com/d/the-industry-standard/rim-co-ceos-resign-new-ceo-stay-the-course-184725.

80. “RIM CEO calls a halt to BBC Click interview,” BBC News. April 13, 2011. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/click_online/9456798.stm.

81. Pimentel, B., “Apple H-P Up, but RIM Weighs on Techs,” Marketwatch. January 23, 2012. http://www.marketwatch.com/story/rim-tanks-but-apple-h-p-keep-techs-afloat-2012-01-23.

82. Ibid.

83. Bustillo, M., “Best Buy CEO Quits in Probe,” Wall Street Journal. April 10, 2012. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303815404577335551794808074.html.

84. Ibid.

85. Ibid.

86. D’Innocenzio, A., and M. Chapman, Michel, “Brian Dunn, Best Buy CEO Resigns Amid Internal Probe,” The Associated Press via The Huffington Post. April 10, 2012. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/04/10/best-buy-ceo-quit-over-pe_n_1416195.html.

87. Cheng, A., “Best Buy’s Dunn Quits Amid Conduct Probe,” Marketwatch April 10, 2012. http://articles.marketwatch.com/2012-04-10/industries/31316789_1_ceo-change-restructuring-investors.

88. D’Innocenzio, A., et. al., Op. Cit.

89. Reuters, “WellPoint shares rise on CEO resignation,” MSNBC. August 29, 2012. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/48826114/ns/business-us_business/t/wellpoint-shares-rise-ceo-resignation/#.UMaVAbvy6oc.

90. “Wednesday’s Biggest Gaining & Declining Stocks,” Marketwatch. August 29, 2012. http://secure.marketwatch.com/story/wednesdays-biggest-gainers-decliners-2012-08-29.

91. Terhune, C., “WellPoint CEO Angela Braly Quits, Bowing to Investor Pressure,” Los Angeles Times. August 29, 2012. http://articles.latimes.com/2012/aug/29/business/la-fi-wellpoint-ceo-out-20120829.

92. Matthews, A.W., “WellPoint’s Braly Quits Amid Pressure,” Wall Street Journal Online, August 28, 2012. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444327204577617943525945430.html.

93. Terhune, C., “WellPoint CEO Angela Braly Quits, Bowing to Investor Pressure.” Los Angeles Times. August 29, 2012. http://articles.latimes.com/2012/aug/29/business/la-fi-wellpoint-ceo-out-20120829 Op. Cit.

94. Edney, A., “Vivus Obesity Pill Wins FDA Panel Nod; NeuroSearch Surges,” Bloomberg. February 23, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-02-22/vivus-weight-loss-pill-qnexa-wins-backing-of-fda-advisory-panel.html.

95. Ibid.

96. Goldman, D., “XM-Sirius Merger Approved by DOJ,” CNNMoney, March 24, 2008. http://money.cnn.com/2008/03/24/news/companies/xm_sirius/index.htm.

97. Reuters News notes that Rambus has incurred: “more than $300 million in legal bills since...1990... as it sued the biggest names in the business for infringing some of its more than 1,000 patents.”

98. Levine, D. and N. Randewich, “Rambus Loses Antitrust Lawsuit, Shares Plunge,” Reuters News, November 16, 2011. http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/11/17/us-rambus-micron-verdict-idUSTRE7AF1XL20111117.