10. Flight to Safety

“There is in the course of human events no stability and consequently no safety.”

—Ludwig Von Mises1

Flights to safety and quality periodically arise during financial crises or periods of sustained market turbulence. Fear replaces greed as the main emotion in the market, and the effects are devastating. Sometimes capital preservation is the primary goal. This chapter is about fear—the fear of large losses—and about how traders behave in the face of such fear. It is about the flight to safety.

Reducing Risk

At their heart, all flights to safety or quality are attempts to reduce risk. Ironically, the flight itself can be fraught with risk. Once there, remaining invested in safer assets may entail considerable opportunity cost—as some safe havens such as gold don’t earn any interest.

Flights to safety are triggered by a sudden shift in risk preferences among market participants. The shift in risk preferences is, in turn, triggered by losses (usually due to falling prices) or the fear of losses. In days gone by, flights to safety were exemplified by bank runs where worried depositors rushed to get their money out of troubled banks before they failed. The introduction of government-mandated deposit insurance helped eliminate most bank runs in developed countries.2

During financial crises correlations of different assets tend toward one. This means that a portfolio that was once diversified might no longer be so during a financial crisis. Simply stated, diversification fails as all risky assets start to move together. In good times, financial stocks might balance against tech stocks, but in a financial crisis where the market as a whole falls, this type of balance might provide limited, if any, diversification. Essentially, there are two assets during a financial crisis cash (and its equivalents) and everything else. The preferred safe asset in a crisis depends partly on the nature of the crisis. Is it a liquidity crisis or a banking crisis? Is it a currency crisis or a credit crisis? Does fear of inflation or deflation dominate?

When everyone’s trying to get out of the same door at the same time, asset prices can fall far below the values they used to have even days before. Fear feeds on itself, and this alone can send companies (as well as their stock prices) into a seeming death spiral. Liquidity dramatically decreases as fear sweeps through the markets and lenders become unwilling to lend. Both the real and the financial sectors are affected. This means that even sound businesses come under the haze of uncertainty. How bad will it get? Who’s the next to go under? Will we have to fire people next quarter? When will sales pick up? The effects of uncertainty alone can be fatal. You can prepare for uncertainty, you can attempt to predict it, but you cannot control it.

Credit Default Swaps

For businesses, especially those depending on borrowed money, perception is more important than reality. Actually, perception is not more important than reality—perception is reality. Anyone seen as being unable to pay back their debts is in grave danger when a liquidity crisis hits. This was apparent during the European sovereign debt crisis where fear spread from country to country along the periphery of Europe, raising bond yields on mere rumors. Plenty of examples exist. Bear Stearns collapsed for this very reason. To finance its massive investments in financial securities, Bear borrowed overnight in the repo market (the wholesale money market). But when confidence collapsed and it couldn’t borrow enough, it sank. The chairman of Bear Stearns claimed his company was adequately capitalized a week before the crisis hit—and he was right. At the time, its collateral was accepted and it could borrow enough to stay afloat. But just days later, its position was collapsing. The market didn’t value Bear’s assets like it used to. The market’s perception had totally changed. Bear essentially still had the same assets on the books. It was the same company, but perception changed, and we know where the story ends.

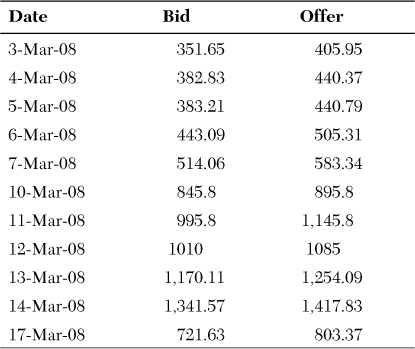

This change is apparent in Table 10-1, which shows the one-year credit default swap (CDS) rates for Bear Stearns from March 3, 2008 to March 17, 2008. The CDS market is essentially an insurance market allowing buyers of CDS to protect themselves against a default by the company or country on which the CDS is written. This feature makes CDS swaps extremely valuable to bondholders interested in hedging their exposure to default risk. Like all insurance, credit default swaps entail the payment of a premium by the buyer to the seller. The premium is a measure of the market’s assessment of the probability of default. Higher CDS rates correspond to a perceived increase in the risk of default.

Table 10-1. Bear Stearns Companies CDS Rates, One Year Tenor—March 2008

Credit default swaps are traded on some notional principal—frequently $10 million for some period or tenor (for example, five years is common). The CDS rate is stated in terms of basis points. Each basis point is one-hundredth of 1%. A CDS rate of 400 is equivalent to 4%. The cost of a CDS contract from the purchaser’s perspective is determined by multiplying the CDS rate by the notional principal. Table 10-1 shows that on Friday, March 14, 2008, the one-year tenor CDS rate soared to 1,417.83 or more than 1,000 points higher than on Monday, March 3, 2008. The cost of insuring $10 million of Bear Stearns debt for a year rose from $405,950 on Monday, March 3, 2008 to $1,417,830 only 12 days later.

Unlike most insurance products, you do not need to have an insurable interest to purchase credit default swaps. This is yet another way to place bets that make money when institutions fail. Some observers argue that not requiring purchasers of credit default swaps to have an insurable interest creates a vehicle for short sellers to increase the probability of default by making it more expensive for highly levered companies such as banks to obtain funding (because traders betting on failure are pushing up the price of “insurance” against default and the rate that such companies can borrow at). Whatever the source, the rise in the one-year CDS rate for Bear Stearns mirrored their problems in raising funds.

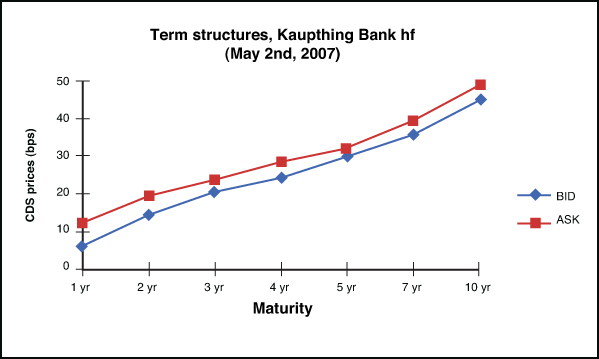

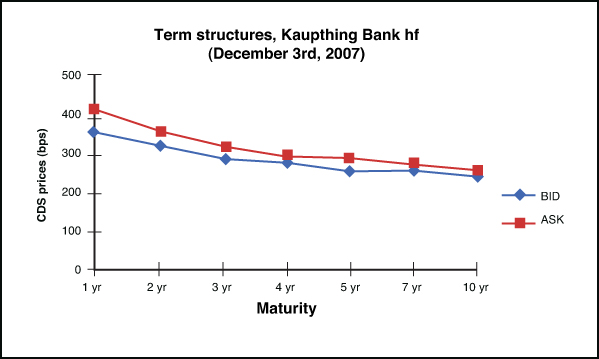

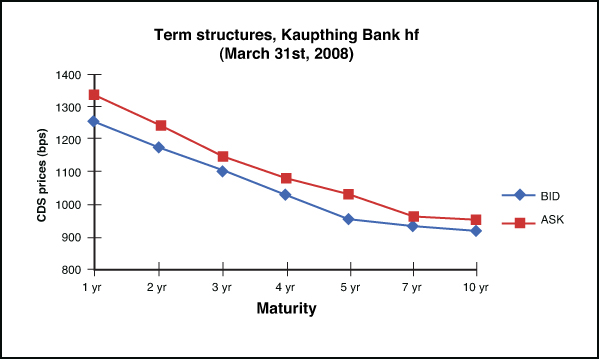

Bear Stearns was not alone in experiencing pressure on its ability to borrow money to finance its operations. Iceland’s major banks faced similar pressures. Figures 10-1 to 10-4 depict the term structure of CDS rates for various maturities for Iceland’s largest bank at the time, Kaupthing Bank hf. Figure 10-1 shows that the cost of “insurance” against default on Kaupthing Bank debt for one-year tenor was about 10 basis points on May 2, 2007 and about 50 basis points for 10-year tenor. Figure 10-2 shows that by December 3, 2007, CDS rates had soared to about 400 and almost 300 basis points for one year and 10-year Kaupthing bank debt, respectively. Figure 10-3 shows CDS rates for Kaupthing bank debt on March 31, 2008. The sharp rise in CDS rates for Iceland’s banks was a matter of government concern as well. Iceland’s banks had attracted substantial foreign deposits prior to 2007 and represented an outsized proportion of the economy. The problems with Iceland’s banking sector hit the value of the Icelandic krona. Geir Haarde, then prime minister of Iceland, argued that the CDS rates were not justified by fundamentals.3 The prime minister also accused certain international hedge funds of trying to precipitate a banking crisis in Iceland. The Financial Times reported on April 2, 2008:

“Iceland is prepared to order direct intervention in the currency and stock markets in an attempt to punish international hedge funds that it claims are attacking its financial system....”4

Figure 10-1. This chart depicts the term structure of CDS rates for Kaupthing Bank hf on May 2, 2007.

Figure 10-2. This chart depicts the term structure of CDS rates for Kaupthing Bank hf on December 3, 2007.

Figure 10-3. This chart depicts the term structure of CDS rates for Kaupthing Bank hf on March 31, 2008.

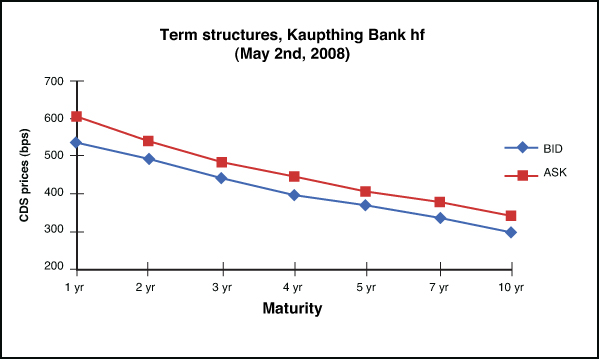

Figure 10-4. This chart depicts the term structure of CDS rates for Kaupthing Bank hf on May 2, 2008.

Figure 10-4 shows that CDS spreads for Kaupthing Bank fell and stood at almost half the levels they were at on March 31, 2008. However, later that year, in the midst of the global financial crisis, the three largest banks in Iceland effectively failed and were nationalized. By early 2009, the fourth-largest bank in Iceland also failed and was nationalized.5

Nature of the Crisis

Financial crises come in many forms. Some are localized to a small group of assets or to one region. Others affect all assets and are global in nature. One type of financial crisis may precipitate another as Iceland showed when the banking crisis sparked a currency crisis. The nature of the financial crisis influences what is a safe asset. A liquidity crisis, which occurred in the wake of the failure of Long-Term Capital Management in August 2008, might spark a flight to safety and quality in U.S. Treasury bond prices. A credit crisis, such as the global financial crisis of 2007–2009 might produce the greatest damage to the economy and financial markets. It may also produce flights to several safe havens including gold, Treasury bonds, and strong currencies. Obviously, in a banking crisis, such as the one Iceland experienced during 2007–2009, deposits in troubled banks may not be perceived as safe. During a currency crisis such as Argentina experienced during 2001–2002, holding foreign currencies may be regarded as safe but prove risky if they are held in local banks in the form of foreign currency-denominated accounts. Indeed, Argentineans experienced this firsthand when the government of President Eduardo Duhalde ended Argentina’s experiment with a currency board monetary system in January 2002 and both devalued the peso and mandated that foreign currency-denominated deposits be converted into Argentinean pesos.

Disastrous economic policies produce fear and promote capital flight as a byproduct. A case in point is Spain during the European sovereign debt crisis. Concern that Spain might be forced to leave the euro zone or local euro-denominated deposits might be redenominated into a new Spanish peseta prompted €343 billion of capital flight over the September 1, 2011 through October 31, 2012 period.6 Anecdotal evidence suggests significant capital flight from Italy, Greece, and Portugal, as well.

As the preceding examples make clear, the nature of the crisis can impact an investor’s choice of preferred safe-haven assets. Two other questions are relevant:

• What are you trying to protect against?

• How long do you need to take refuge?

Sometimes the periodic flights to alternative safe havens reflect conflicting views of what will happen next. For instance, during the global financial crisis concern that the central banks would debase currencies in an attempt to stimulate the world economy led many market participants to invest in gold. At the same time, concern that the economy was weak and the belief that central banks would purchase massive amounts of government debt led others to buy Treasury bonds. As of early 2013, both investments had done very well. However, if the proponents of gold were correct and inflation will increase sharply, holders of Treasury bonds will face the consequences of a massive bond bubble. Conversely, if inflation remains tame, holders of gold might not realize the returns they hoped for.

Gold

Gold is the most famous “safe” asset in the world. It’s been used as a medium of exchange for thousands of years, and is so rooted in popular culture that it has entered the lexicon in a variety of phrases such as “Good as gold,” “Heart of gold,” “Golden rule,” and “Golden Age.” It is a positive word that always conveys a sense of wealth and value. But is gold a reliable store of value? Is it a store of wealth over the long term? Many think so. For instance, the late international currency analyst, Dr. Franz Pick argued:

“Buy gold and sit on it. That is the key to success.”7

If only making and protecting wealth were that easy. Gold is a relatively good store of value in the very long term. However, in time-frames less than a decade, gold is an erratic and unpredictable store of wealth, subject to bubbles, crises, and crashes—just like any other asset.

Gold has been called a store of value for thousands of years, but does it live up to its reputation? In the past 200 years, gold has earned its reputation as a store of value. In the period from 1802–2001, $1 invested in the stock market would have yielded $599,605; invested in bonds would have yielded $952; and invested in Treasury bills would have yielded $304.8 Although the period is longer than any person’s lifetime, each of these investments has large returns (all of these figures, including those for gold, are adjusted for inflation).

How did gold do? How much would you have had if your great-great-grandfather had set up a gold trust fund? Well, you would have lost money. Each dollar invested in gold in 1802 is only worth .98 cents today.9 Not a bad store of wealth, but certainly no way to increase your wealth in the long run. At least gold’s performance is significantly better than that of the U.S. dollar, worth a mere 7 cents in 2001 if held in cash from 1802.

There is even some evidence that gold has returned 0% over the extremely long term. Stephen Harmston for the World Gold Council, in “Gold as a Store of Value” noted that an ounce of gold bought the same quantity of bread in modern times as it did during the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon.

“Across 2,500 years gold has in other words retained its purchasing power, relative to bread at least, and has had a real rate of return of zero.”10

So it appears that historically, gold has lived up to its reputation as a store of wealth. But why would you want to merely maintain your wealth when investing in the stock market has hundreds of years of proven growth and incredible returns? One reason might be, quite logically, that you expect equities to perform poorly for a period of time. Gold is seen as a way to preserve wealth during inevitable crashes in the market. Or maybe you see a major crisis coming and have to batten down the hatches, preparing for the worst. If that happens, gold must be your friend, right? Not only that—you very well might expect to make a pretty penny on such an investment.

The answer is, at best, unclear.

As a trader or investor, you are primarily concerned with preserving and growing wealth. Despite its reputation as a safe asset, gold does not necessarily ensure the preservation of wealth even in the short term. Using history as a guide, it does not present a case for impressive returns in the long run.

The main problem is that gold does not always appreciate in every crisis, and it is subject to its own crises. Gold has gone through several bubble periods in the last century. Although this is great for investors who got in before the bubble, gold has not been a reliable source of value for those who bought amidst the bubble—in fact, for those traders, it has destroyed wealth.

For instance, an investor who bought gold in the spot market at $850 per troy ounce on January 21, 1980—the height of the silver corner—and sold it at $1,710 per troy ounce on October 31, 2012 would have a nominal gain but a real loss. Due to inflation over the January 1980 through October 2012 period, gold would have to sell for $2,527 per troy ounce for the investor just to break even in real terms. Given that taxes are paid on nominal gains, the price would have to rise even more before you earned a real profit—and this ignores any storage or insurance costs incurred. Lesson: Timing is everything.

What about the performance of gold during financial crises or during world wars? Surely gold must surge in value during such periods of intense uncertainty and destruction? Nope. In the same paper referenced earlier, Mr. Harmston notes that gold experienced sharp declines during World Wars I and II and immediately thereafter.11

Ironically enough, in modern history’s greatest crises, the two world wars, gold actually lost value. The World Wars were two monumental periods of extreme destruction, loss of life, uncertainty, rationing, and chaos, and yet gold—the safe haven—actually lost value.

This also has a modern parallel. The stunning bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers on Monday, September 15, 2008 triggered a sharp rise in the price of gold exactly as one would expect. The rally continued for a couple of weeks. Yet, the rally was relatively short-lived because by the end of October, the price of gold fell below where it stood on the Friday before the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy. In the midst of the 2007–2009 global financial crisis, the price of gold fell. Bloomberg News reported:

“...In October 2008, gold prices tumbled 18 percent as the most severe slump since the Great Depression spurred losses in global equity and commodity markets....”12

Put differently, in one of the greatest shocks to the world financial system since 1929, when there was uncertainty whether the financial system would survive, gold—the “safe haven” asset of choice—lost value.

To be sure, gold later went on to rally more than 20% over the next two months.13 A similar example occurred on September 23, 2011 during the sovereign debt crisis when gold fell more than 100 dollars per troy ounce and 9.3% over two days.14

The point is that gold is an asset like any other, one that does not in fact—despite its reputation—always appreciate during times of crisis. Indeed, one study suggests that the increasing popularity of gold for speculative and hedging purposes means that it can no longer be “an effective safe haven asset.”15

Again, whether an investment in gold is profitable depends on where you get in and where you get out. Anyone who bought gold at the current peak of over $1,900 per troy ounce during July 2011 would still be underwater as of February 2013. Short-term flights to gold may also be profitable. For instance, gold broke $1,000 per troy ounce on March 17, 2008, in the wake of the market sell-off that followed the announcement of the forced sale of Bear Stearns to JPMorgan Chase initially for $2 per share. But the price rise did not last. Gold fell sharply over the next couple of days.

By now it should be apparent that gold is not an asset that always gains in value during a crisis, let alone one that maintains value. But, to be fair, that doesn’t make gold a bad “safe haven” investment. This is not to say that gold loses value in every crisis. Indeed gold did surge 8% in the week after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.16

What is safe is relative. In World War II, gold obviously lost much less value than Nazi currency, only some of which was later convertible to Deutsche marks at a favorable rate after the war. Military yen in Hong Kong became absolutely worthless mere weeks after the unconditional surrender of Japan. Gold that could be safely smuggled or protected may have been a much better store of value than say, a European mansion, which cannot be saved from advancing troops. These scenarios seem outlandish, and we hope they remain so. They are brought up to reinforce the point that risks are constantly changing, and assets that seem safe can sometimes, often remarkably quickly, become risky. That’s why vigilance and diversification are the hallmarks of a successful wealth protection strategy—not reliance on any one asset that is supposedly always “safe.”

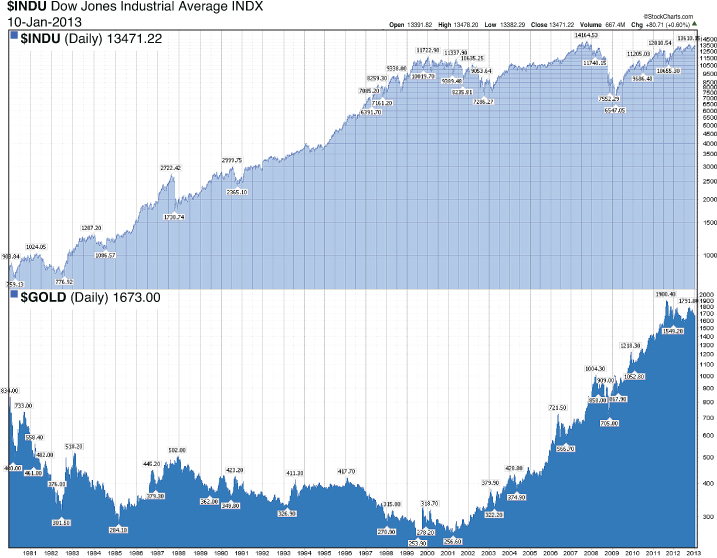

Gold has many positive qualities. These include a long history of use as money, near universal acceptance, and relatively good portability in small quantities. However, it lacks several qualities it is believed to possess: always appreciating during major crises, and reliably storing wealth over periods less than a decade or more. Figure 10-5 compares the behavior of gold prices and the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

(Chart courtesy of Stockcharts.com)

Figure 10-5. Gold and the Dow Jones Industrial Average

Gold, like any asset, is always worth something, yet whether it is a reliable store of value (or a good investment) is another question entirely. Investors who bought gold in the early ’80s saw negative nominal returns until the mid-2000s. Investors who instead put their money in the stock market in the early ’80s and sold at the low of the late 2000s financial crisis would have made around eight times their original investment. Those who sold at the high would have made around 18 times.17

In more recent times, gold saw large gains from 2001, and has appreciated in value due to the financial crisis. However, the idea that gold is always a reliable store of value, or will always go up in a crisis is, quite frankly, inconsistent with the historical evidence. In short, gold might be a good investment, but it is not necessarily always a safe one.

Treasuries

Besides gold, U.S. Treasury securities are also commonly seen as a reliable safe haven asset. Given that they are backed by “the full faith and credit of the United States,” they are seen as “safe” investments. Of course, any bond is only as safe as long as the issuer’s ability to repay remains intact. Although a U.S. default seems extremely unlikely because the U.S. government can always print dollars to repay the principal due, S&P’s downgrade of U.S. debt from AAA to AA+ underscores the fact that the yield on Treasuries may no longer be the true risk-free rate.18

Treasuries are also a good example of how what is considered a safe haven asset—among even the range of Treasury securities with different maturities—changes over time. A flight to safety used to mean the purchase of U.S. Treasury bills (that is, U.S. Treasury debt with initial maturities of one year or less) rather than the purchase of long-term U.S. Treasury bonds. The almost 4% drop in the Dow Jones Industrial Average on Friday, October 16, 1987 led to a flight to safety and rally in U.S. Treasury bill prices after the market closed but not U.S. Treasury bonds. During the 23% crash in stock prices on Monday, October 19, 1987, long-term Treasury bond prices were down for the day. Overnight, however, U.S. Treasury bonds had their largest one-day rally ever. Since then, a sharp fall in equity prices typically precipitates a rally in Treasury bond prices.

Investors in U.S. Treasuries bear the risk that the yield on the securities might not fully compensate for realized inflation. With interest rates at extreme lows, massive federal budget deficits likely to continue for several years, and the Federal Reserve engaged in its third program of quantitative easing, holders of Treasuries are in a very precarious position should real interest rates rise or inflation increase.

During early September 2012, 30-year Treasury bonds were yielding 3.27%.19 At the time, the realized inflation rate was about 3.6%. Assuming the recent past is prologue and the expected inflation rate was also 3.6%, investors in Treasury bonds bought a losing investment. This is because the recent rate of inflation was above the Treasury bond yield. Given that nominal capital gains are taxable even when real capital gains do not exist, investors should want a return in excess of the expected inflation rate. Some might say that this means the market believes that the expected rate of inflation is significantly lower than 3.27%.

Currencies

Throughout 2011, the Swiss franc rallied as a “safe haven” amidst the European debt crisis. There were even hyperbolic claims from some, such as forexblog.com, which boldly declared, on June 23, 2011, that the “Swiss Franc is the Only Safe Haven Currency.”20 Hopefully, they were not invested in this position, as less than three months later there was a surprise announcement.

On September 6, 2011, the Swiss National Bank announced it was taking decisive action to stem the rise of the franc:

“The current massive overvaluation of the Swiss franc poses an acute threat to the Swiss economy and carries the risk of a deflationary development.

“The Swiss National Bank (SNB) is therefore aiming for a substantial and sustained weakening of the Swiss franc. With immediate effect, it will no longer tolerate a EUR/CHF exchange rate below the minimum rate of CHF 1.20. The SNB will enforce this minimum rate with the utmost determination and is prepared to buy foreign currency in unlimited quantities.

“Even at a rate of CHF 1.20 per euro, the Swiss franc is still high and should continue to weaken over time. If the economic outlook and deflationary risks so require, the SNB will take further measures.”21

Jeremy Cook, chief economist at currency broker, World First, explained:

“...The Swiss franc has lost close on 9% in the past 15 minutes. This dwarfs moves seen post-Lehman brothers, 7/7, and other major geo-political events in the past decade.”22

Bloomberg News reported the franc soon weakened 9.5% versus the dollar and a minimum of 8.2% against the 16 most-active currencies.23 The Norwegian krone rose against its 16 most-traded currency counterparts. This led some, like Stephen Gallo, head of market analysis at Schneider Foreign Exchange in London, to suggest that the krone would become a “substitute” for the franc. He noted:

“The Norwegian krone has been very strong today against most currencies, which suggests that euro-krone becomes a substitute or proxy for euro-Swiss.”24

The krone wasn’t the only currency attracting attention as a safe haven asset. Some investors fled to the Japanese yen. As the currency of one of the largest economies on earth, it seems a natural choice. On July 10, 2012, Daragh Maher, currency strategist at HSBC, called the yen “definitely right at the top” in regard to safe haven currencies.25 He expressed confidence in the Japanese yen, despite some potential headwinds. On a more ominous note, he also claimed that “we’re running out of safe havens.”26

Yet, the outlook here, too, was cloudy. In 2012, Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio was estimated to be 236%.27 Compare that to Spain’s 79% level. Japan was also dealing with deflation, which Richard Jerram, Macquarie Securities head of Asian economics called “...extremely corrosive.”28

However, despite the cloudy outlook, the yen has slowly but surely appreciated against the U.S. dollar since 2007. Its future is uncertain given the January 22, 2013 joint statement by the Japanese Government and the Bank of Japan for a 2% inflation target.29 Some observers fear that the action by the Japanese authorities to weaken the yen may precipitate a currency war.30 Simply stated, there are no safe bets in the currency sector—only changing risk profiles.

But what about the elephant in the room—the U.S. dollar? It remains the world’s reserve currency. It is the most liquid and most-used currency. In a recent survey of hedge fund managers, it was ranked the top safe-haven currency with 48% of the vote.31 The Swiss franc received 20% preference, while the Norwegian krone received 10%. Sterling, the Australian dollar, yen, and Canadian dollar rounded out the list with 9%, 7%, 3%, and 3%, respectively.

One of the main benefits frequently cited in favor of the U.S. dollar is its massive liquidity. Furthermore, at this juncture, simply no currency is yet able to replace it. The only plausible candidate—the euro—is still (as of early 2013) mired in a crisis of confidence that the currency will even survive, let alone present a stable alternative for global commerce.

Currencies can play a vital role in any portfolio and this is even truer during liquidity crises. In a liquidity crisis cash (or its equivalents such as Treasuries) is king and is the only asset that matters. Over the long run, however, holding cash is almost always a great way to destroy wealth.

Cash is the asset many instinctively move to during a crisis, and for good reason—the liquidity and security of cash are all important in most crises (save currency crises). Oftentimes, cash provides that certainty. However, of all the asset classes—equities, bonds, treasuries, cash, and gold—cash did the worst job at preserving wealth—holding a mere 7% over 200 years. This brings up the paradox of wealth preservation.

The Paradox of Wealth Preservation

The assets most commonly believed to be “safe” stores of value actually have a track record of destroying wealth.

In a way, this makes perfect sense. Investors are rewarded for bearing risk. Junk bonds have higher interest rates than Treasuries. But in a growing economy, in a world with inflation, a fear of taking risk can have dramatic wealth-destroying consequences.

This is why it’s important to know how long you will seek refuge in any particular safe haven. After a crisis, a “safe haven” may be just as likely to bleed value as preserve it. As market conditions change, safe havens can become hotspots of selling, not safety.

In fact, the paradox of wealth preservation is hurting the very people who would benefit the most from the growth potential offered by the stock market. Gallup did a survey of attitudes about investing and found that:

“Upper-income and college-educated Americans—prefer stocks and mutual funds, while Americans with lower incomes and those with no college education favor savings accounts or CDs as the best investment.”32

That might have been the right attitude at the height of the financial crisis, but it is an absolutely terrible strategy to grow wealth over the long term. They also noted that recent price trends strongly influence many Americans’ belief in whether stocks are the preferred long-term investment.33

Because of this, average investors are more likely to invest in the market at precisely the wrong time. This type of thinking essentially leads to a “buy high, sell low” strategy led by misguided attempts to preserve rather than grow wealth.

Ultimately, those that merely seek to preserve their wealth by staying in safe haven assets for extended periods may end up losing it. Defensive investing might be a smart tactic at a time of intense uncertainty—but it’s not a long-term strategy for growing wealth. You need to know the difference between risk avoidance and risk minimization. Selecting between the two becomes more difficult during times when the market seems to shift from a “risk-on” mode to a “risk-off” mode and vice versa, as it did in much of 2011 and part of 2012.

What Is Safe?

Beyond material needs like food, water and shelter, what has value at any time is highly subjective.

At a speculative level, every asset class is vulnerable to large swings of value. Salt was once vitally important to the world economy. Roman soldiers were even paid in salt. This legacy lives on as the word salary is derived from salarium argentum, literally salt money in Latin.34 Salt is a great example of an asset that once contained enough value to be accepted as a salary for soldiers—yet is now so cheap it is liberally poured on 99-cent French fries and eaten.

Ironically, although salt is not viewed as a store of value in the modern era, some claim it has been more consistent as a store of value than gold.35

Gold has been subject to several large bubbles and, as a result, large crashes. Although this obviously allows speculators to profit off of such bubbles it seriously undermines gold’s claim to be a consistent store of value. Maybe the Romans had it right.

In the long run, prudent investors must diversify (in order to protect against sudden shocks to any asset class) and change with the times (adapting weights and asset classes with the times). Some assets like equities have performed well over long periods of time. However, such assets are unlikely to be much in demand during a risk-off period when investors are in a flight to safety and quality.

Even the supposed arbiters of quality, the ratings agencies, do not always agree on what is a AAA asset. Nicole Bullock in the Financial Times wrote about a bond issue that was rated AAA by Standard and Poors but Fitch disagreed and lost the opportunity to rate the issue:

“...Fitch Ratings issued a statement saying it would not have rated the bonds triple A. ..., and “was ultimately not asked to rate the deal...”36

Fitch’s conservative stance led to its not being asked to participate, and potentially left prospective investors unaware of certain risks. This just reinforces the point that even a AAA rating may not be truly AAA, and that not all ratings agencies share the same view about the safety of any particular asset.

Trading Lessons

The weight of history suggests that investing in a diversified portfolio of equities is one of the best ways to grow wealth in the long run. However, as noted economist John Maynard Keynes once said: “In the long run we are all dead.” Investors must be able to survive short run shocks to their wealth and this means periodically moving assets into safe havens. However, growing wealth over time requires that funds be shifted back into risky assets as well.

The truth of the matter is that all asset classes have substantial and changing risk profiles and frequent re-evaluations of your overall risk profile is essential.

Merely looking at the risk of assets you own is not enough. Evaluating the risk profile of the market as a whole and other popular asset classes is necessary.

Cash and gold generally maintain value in the short run, but have slowly bled (in the case of gold) and hemorrhaged (in the case of cash) value in the past 200 years. The weight of history suggests that gold may be a good investment, but it is not always a safe one.

Cash, on the other hand, is indispensable during a liquidity crisis—but keeping most of your assets in cash is a poor way to grow wealth over the long run. You need to change your strategy as the times change. Although you want to maximize gains when the market is growing, you want to be prudent and realize the good times—or bad times—won’t last forever.

Diversification provides some protection against risk in normal markets. However, during a financial crisis, diversification might not help as the correlations for risky assets all tend to move toward one. You want to be conservative enough in good times that you have the resources to take advantage of the bad times. You want to prepare for bad times, but you also need to be ready to seize opportunities in good times.

Endnotes

1. Von Mises, L, Human Action, p. 113, Yale University Press, 1949.

2. The effective collapse of Northern Rock Bank in 2007 and its subsequent nationalization in 2008 is a puzzling exception. The Economist attributes the bank run partly to the bank’s greater reliance on funding from the wholesale money markets than from retail deposits. The Economist, “Lessons of the Fall.” October 18, 2007. http://www.economist.com/node/9988865.

3. Armitstead, L., “Iceland Shows Cracks as the Krona Crashes.” The Telegraph, March 23, 2008. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/banksand-finance/2786820/Iceland-shows-cracks-as-the-krona-crashes.html.

4. Ibison, D., “Iceland Threatens Direct Intervention in Markets.” Financial Times, April 2, 2008. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/051a47fc-0059-11dd-825a-000077b07658.html#axzz2D8uCUCHX.

5. Ibison, D., “Iceland Nationalises Straumur-Burdaras.” Financial Times, March 9, 2009. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/22db4400-0c86-11de-a555-0000779fd2ac.html#axzz2D8uCUCHX.

6. Aguado, J., “Capital Leaves Spain for 14th Month Running.” Reuters News, October 31, 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/10/31/us-spain-capital-idUSBRE89U0JR20121031.

7. Amerigold Hall of Quotes. Dr. Franz Pick. http://www.amerigold.com/hall_of_quotes/

8. Mobius, M., Equities: An Introduction to the Core Concepts. John Wiley & Sons (Asia) Pte. Ltd. 2007.

9. Ibid.

10. Harmston, S., “Gold as a Store of Value.” World Gold Council, Research Study No. 22, November 1998. http://www.newworldeconomics.com/archives/2011/041011_files/WGC%20purchasing%20power%20of%20gold%20copy.pdf.

11. Ibid.

12. Roy, D. and N. Larkin, “Gold Plunges More Than $100 as Investors Sell.” Bloomberg News. September 23, 2011. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-09-23/gold-declines-more-than-100-in-new-york-on-sales-driven-by-margin-calls.html.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Baur, D. G. and K. J. Glover, “The Destruction of a Safe Haven Asset?” August 31, 2012. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2142283 or http://dx.doi.org/102139/ssrn.2142283.

16. Miley, J. “The US Economy Since 9/11.” Kiplinger. http://www.kiplinger.com/slideshow/September_11_economy/7.html#top.

17. StockCharts.Com, Historical Chart. DJIA vs. Gold. 1980–Present. http://stockcharts.com/freecharts/historical/djiagold1980.html

18. “United States of America Long-Term Rating Lowered to ‘AA+’ Due to Political Risks, Rising Debt Burden; Outlook Negative.” Standard & Poor’s. August 5, 2011. http://www.standardandpoors.com/ratings/articles/en/us/?assetID=1245316529563

19. Braham, L., “The Risks Lurking in ‘Safe Haven’ Treasury Bonds.” Bloomberg News. September 14, 2011. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-09-13/the-risks-lurking-in-treasury-bonds.html.

20. Kritzer, A., “Swiss Franc is the Only Safe Haven Currency.” Forex Blog. June 23, 2011. http://www.forexblog.org/2011/06/swiss-franc-is-the-only-safe-haven-currency.html.

21. “Swiss National Bank, “Swiss National Bank Sets Minimum Exchange Rate at CHF 1.20 per Euro.” press release, September 6, 2011. http://www.snb.ch/en/ifor/media/id/media_releases?LIST=lid1&EXPAND=lid1&START=41#lid1.

22. Wearden, G., “Swiss Bid to Peg ‘Safe Haven’ Franc to the Euro Stuns Currency Traders.” Guardian, September 6, 2011. http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2011/sep/06/switzerland-pegs-swiss-franc-euro.

23. Bennett, A. and L. Meakin, “Franc Plunges Most Ever Versus Euro.” Bloomberg News, September 6, 2011. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-09-06/franc-slides-against-dollar-euro-as-snb-vows-to-stand-by-currency-target.html.

24. Ibid.

25. “‘Yen Is Top Safe Haven Currency’” HSBC’s Maher Says.” Bloomberg News, July 10, 2012. http://www.washingtonpost.com/yen-is-top-safe-haven-currency-hsbcs-maher-says/2012/07/10/gJQAvngBbW_video.html.

26. Ibid.

27. Bernard, S.L. and V. Cignarella, “Japan’s Safe-Haven Status Won’t Defy Logic Forever.” Wall Street Journal. August 10, 2012. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390443404004577580994012343760.html.

28. Ito, A., “Japan Learns to Live with Deflation.” Businessweek. January 27, 2011. http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/11_06/b4214014587950.htm.

29. “Joint Statement of the Government and the Bank of Japan on Overcoming Deflation and Achieving Sustainable Economic Growth,” January 22, 2013. http://www.boj.or.jp/en/mopo/mpmdeci/state_2013/index.htm/.

30. Fujioka, T., and S. Kennedy, “Japan’s Amari Says Markets Sets Currencies Amid Yen Criticism,” Bloomberg News, January 27, 2013. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-26/amari-says-japan-s-focus-is-to-end-deflation-amid-yen-criticism.html.

31. Dickinson, C., “U.S. dollar is preferred safe haven currency for hedge fund managers, according to poll results.” Hedge Funds Review. July 18, 2012. http://www.hedgefundsreview.com/hedge-funds-eview/news/2192648/us-dollar-is-preferred-safe-haven-currency-for-hedge-fund-managers-according-to-poll-results.

32. Saad, L. “Americans’ Faith in Stocks as Best Investment Partly Restored.” April 27, 2010. http://www.gallup.com/poll/127529/americans-faith-stocks-best-investment-partly-restored.aspx.

33. Ibid.

34. Cowen R. “The Importance of Salt.” May 1999. http://mygeologypage.ucdavis.edu/cowen/~GEL115/salt.html.

35. “Gold to Salt Price Ratio. Illusion of Prosperity.” June 8, 2010. http://illusionofprosperity.blogspot.com/2010/06/gold-to-salt-price-ratio.html.

36. Bullock, N., “Agencies at Odds Over Ratings.” Financial Times. April 8, 2012. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/66738d12-7f5b-11e1-a06e-00144feab49a.html#axzz2D8uCUCHX.