11. Why Most Traders Lose Money

“Cut your losses short and let your profits run.”

—Trading adage

Nothing is more central to trading than the question: Who makes money and from whom? Trading profits are not equally distributed across markets. Rather, they are usually concentrated in the hands of a few. Many large investment banks have relatively few days when they lose money from trading. The Financial Times reported on March 2, 2011 the experience for 2010:

“...Goldman’s traders had 25 money losing days...JPMorgan [had] ... its only eight losing days coming in the first quarter. Morgan Stanley had 38 losing days in 2010...”1

The lopsided number of winning days experienced by the trading desks of major investment and commercial banks is not unusual. Moreover, many of the winning days have been very profitable. For instance, the Financial Times reported a year earlier on March 2, 2010:

“Goldman Sachs made at least $100m (£67m) in net trading revenues on 131 days last year [2009], equivalent to once every other trading day...”2

There are approximately 252 trading days per year after excluding weekends and holidays. That means Goldman had $100 million+ revenue days more than half the time in 2009. What explains the apparently superior trading performance of Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, and Morgan Stanley as measured by the low number of losing days and, in Goldman’s case, the large amounts made? What does the low number of losing days suggest about likely trading strategies the banks pursue? The answer to these questions is that consistent trading profits come largely from market making, acting as a middleman. Although market making, or flow trading, is a form of trading, it entails limited risk. It is also something that most retail market participants couldn’t do (profitably) even if they wanted to.

The Banks

Market making is an important economic function, but some observers take a dim view of the size of profits some banks have been making. In a 2010 speech, Thomas Peterffy, billionaire founder of Interactive Brokers, argued that bank profits from market making are large as evidenced from their large volume of derivative transactions:

“The root of the problem, as always, is short-sighted greed on the part of the brokers. The banks simply take the opposite side of the customers’ orders at prices that leave the banks with undisclosed but huge profits. ...Even the more modest estimates exceed $100 billion per year, worldwide. Customers are on the other side of those trades. Customer losses are on the other side of those bank profits....”3

This is no claim by a man who hates the free market, or by some Luddite who does not understand the modern market. Instead, Mr. Peterffy argues for the reform of a system he sees as flawed.

Many investment banks also operate significant prop (i.e., proprietary) trading desks. However, large and consistent trading profits come from market making. Most of the money investment banks make from flow trading comes from fixed income, currency, and commodity markets (both spot and over-the-counter derivatives). Money is made from taking the other side of order flow from institutional investors rather than from individuals trading for their own accounts. Investment banks benefit from the relative opacity of these markets compared to exchange- traded markets.

The consistency of the trading profits of investment banks from flow trading pales in comparison with the enormous and consistent profitability of high-frequency trading (HFT) firms. A recent study of the e-mini S&P 500 stock index futures markets [2012] reports evidence that HFT trading firms are consistently profitable with incredible (frequently double digit) Sharpe ratios (a measure of reward per unit of risk taken).4 This suggests that extraordinary profits are not simply compensation for risk. That’s because these firms use low-risk strategies in ways the average trader cannot hope to emulate. They make thousands and thousands of small, virtually risk-free trades. They are fast, ruthless, and constantly watch the market at the microsecond level with the focus and drive only a machine could provide. The same cannot be said for most of the thousands of other participants in the e-mini S&P 500 stock index futures market. The persistence of abnormally large gross profits (and presumably high net profits) suggests that markets are not efficient over the very short periods of time in which HFT firms operate. Profits were greater for HFT firms that were faster and more aggressive—i.e., those that were also liquidity takers.5

Contrast the previous reports of consistent trading profitability of banks and HFT firms with the experience of many individual retail foreign exchange (FX) traders. Barron’s reports that individuals trading currencies through dedicated foreign exchange trading firms collectively traded $125 billion per day with the average trader making just a few trades a day. Yet, even though trading costs are relatively low:

“...Roughly three-quarters of individual investors who trade through forex firms ... lose money, resulting in an estimated client-attrition rate of 15% to 25% a year...”6

The article goes on to note that the per-client annual revenue of one FX firm is approximately equal to the average account size of its clients.7

A similar phenomenon has been noted for small (i.e., lightly capitalized) futures traders even though leverage is far smaller than in the retail FX market, and futures trading frequency is far lower. Trading in FX as well as futures is a zero-sum game (i.e., for every dollar won by someone, there is a dollar lost by the counterparty or counterparties) ignoring transaction costs.8 The question naturally arises as to why so many small FX and futures traders lose money if the market is efficient? Ignoring transaction costs, if the market were efficient, the number of winners and losers would be about equal. Regardless of whether the market is actually efficient, or even approaches efficiency, the fact so many small traders lose probably reflects poor trading practices.

The large consistent profitability of the flow trading operations of big banks and many HFT firms is both enviable and potentially discouraging to individual traders. Is there any hope that individuals can trade profitably? Yes. You cannot expect to beat the large banks or HFT firms at their own game. Rather, individual traders must look for trading opportunities beyond market making. They must be prepared to hold positions longer. They must also pursue strategies and adopt trading rules that limit their losses.

Behavioral Finance

Trading is about decision making, usually but not always under conditions of uncertainty. A short decision timeframe is also common. Classical economic theory assumes that individuals make rational economic decisions. Classical economic theory assumes that individuals are rational, risk averse, and seek to maximize their expected wealth (or more correctly, economists would argue, their expected “utility of wealth”). In a world of uncertainty, this means that traders would use statistical theory to guide their cold, calculated financial decisions. Considering that many, if not most, people do not meet this definition for strict rationality, what actually drives their decisions?

It has long been said that markets run on fear and greed, and now science has backed up that assertion. A growing strand of literature in both economics and finance argues that behavioral factors affect decision-making. This is known as behavioral finance. Behavioral finance assumes that investors do not always behave rationally and that failure to behave rationally may impact the behavior of speculative prices. The failure to behave rationally arises because investors frequently fall prey to various cognitive illusions. These are akin to optical illusions but concern how cognition can be fooled. Put differently, traders fall prey to decision pitfalls. Avoiding large trading losses means avoiding decision pitfalls. Although there are numerous behavioral factors, the ones most pertinent to trading are overconfidence, risk aversion, loss aversion, the disposition effect, mental anchoring, and the failure to use statistics in decision-making.

Overconfidence

Investors tend to be overconfident about their ability to predict the future. Research by Brad Barber and Terrance Odean [2001] reports a gender bias in overconfidence.9 Men are more likely to be overconfident than women. One implication of overconfidence is that market participants are surprised more frequently than they should be. Traders often do not anticipate as wide a range in potential outcomes as frequently occurs. This results in larger forecast errors and larger market moves in response to news contained in forecast errors. There are other implications, too. For example, overconfident traders trade more frequently, incurring greater transaction costs and earning lower profits or incurring larger losses. Because they are overconfident, they trade in larger size. They cut their profits short. They let their losses run. They take on more risk. Alternatively stated, their security positions are less diversified because they are confident that they are right.

Risk Aversion

Classical economic theory assumes that most individuals are risk averse. One implication of this is that investors demand a higher expected return, the greater the perceived risk of an investment. Confronted with a choice between a gamble paying $100,000 with probability of 0.70 (and $0 otherwise), or a certain payout of $70,000 cash, the risk averse individual would take the certain $70,000 in cash because the expected values of the two choices are the same but the risk is lower for the cash choice. In contrast, a risk-seeking individual would take the gamble in the hope of winning $100,000 while a risk-neutral individual would be indifferent between the two choices.

Loss Aversion

Loss aversion turns the risk preferences of most individuals (that is, risk aversion) on their head when potential losses are involved. Specifically, it suggests that investors are willing to assume risk to avoid a potential loss. That is, investors exhibit risk-seeking behavior toward potential losses even though they exhibit risk averse behavior toward potential gains. Most people are more likely to take large risks in order to prevent a loss than to obtain a profit. This has an important trading implication—namely, most individuals are reluctant to cut their losses short. This is exactly what you don’t want to do. Ironically, this instinct leads traders to risk money in search of capital preservation, not profit.

Disposition Effect

Closely related to loss aversion is the disposition effect. This suggests that individuals are more likely to dispose of winners or profitable trades and retain losers or unprofitable trades. Many individuals exhibit such behavior. There is evidence in the academic literature that many individuals exhibit greater risk-taking after earning gains and take less risk after incurring losses. This is known as the “house money effect.”10 That is, they don’t treat their paper profits as their own money and, hence, are more willing to risk it.

Mental Anchoring

Mental anchoring refers to the tendency to focus on or over-emphasize one piece of information. Many investors focus on the price that they entered a security position at and, if they are losing money, have their goal be to get out at even (that is, without incurring a loss). This is another factor leading traders to hold onto losing positions and, worse yet, to engage in trades where they are willing to risk a lot for zero or minimal gain. When holding a losing position, don’t worry about where you got in; worry where you can get out.

Heuristics Not Statistics

Kahneman and Tversky [1979] argue that individuals do not use statistical theory to make decisions under conditions of uncertainty. Rather, they argue that most individuals use heuristics, or convenient rules of thumb, to make decisions.11 As a result, significant systematic errors might arise in decisions. For example, Kahneman and Tversky argue that individuals use representativeness as the basis of prediction. Representativeness can also be viewed as a stereotype. However, use of this heuristic ignores factors that individuals should use in assessing probability. Factors ignored include prior probability (the base rate frequency of occurrence). Bayes’ theorem is the notion that the probability a person assigns to a given outcome changes with evidence, sample size (perceived probability is viewed as independent of sample size), and posterior probability (odds that the sample came from a given population). One of the implications of Kahneman and Tversky’s study is that individuals are not incorporating information using Bayes’ theorem when making decisions. This is likely to lead to irrational and suboptimal decision making.

Along the same lines, individuals might attribute large sample probabilities as being appropriate for small samples. The quintessential example is the well-known experiment where two groups flip a fair coin 20 times and record the number of heads and tails. The wrinkle is that one group flips an imaginary coin while the other group flips a real coin. The group flipping the imaginary coin tends to have almost an equal number of heads and tails on average while the group flipping the real coin reports repeated runs of heads or tails. The group flipping the imaginary coin has imposed the large sample probability of flipping heads or tails of a fair coin (50%) on a small sample. They have ignored the potential for runs (several heads or tails in a row) in small samples. The principal implication for trading is that you must be careful not to apply probabilities (and strategies) applicable to large samples to small samples.

A Tale of Two Losses

Notwithstanding the incredible trading performance of HFT firms in the e-mini S&P 500 stock index futures market noted earlier in this chapter, losses are an integral part of trading or investing. This is true for both the naïve and the astute. Consider the following example of a rogue trader and a sovereign wealth investor. In March 2008, the government of Singapore Investment Corporation (GIC), one of two sovereign wealth funds in Singapore, acquired a substantial stake in UBS, a major Swiss Bank, for $15 billion.12 Unfortunately for GIC, UBS fell after its investment. Despite substantial paper losses GIC continued to hold its stake in UBS and, in January 2011 announced its intention to hold the stock for “many years.”13 The news worsened for UBS investors in September 2011 when UBS discovered that one of its traders, Mr. Kweku Adoboli, had lost $2.3 billion from unauthorized trades. The Financial Times reported on September 20, 2011:

“...GIC is sitting on a substantial loss—close to $7.4bn—on its UBS stake, acquired for $15bn three and a half years ago...”14

Ironically, Adoboli started his rogue trading at about the same time that GIC—a long-term value investor—purchased its stake in UBS. It is important to point out that neither loss occurred overnight. Although rogue trading and value investing are completely different, Adoboli and the managers of GIC seemingly share some characteristics in common. Namely, both refused to cut their losses short. Both Adoboli and the managers of GIC had many opportunities to cut their losses when they would have been far smaller. To be sure, UBS’ stock price fell sharply upon revelation of rogue trading by Adoboli in September 2011, which hurt GIC. However, it was already substantially below where GIC acquired its UBS stake.

The mathematics of large losses is difficult to overcome. Having lost about 50% of their investment, the managers of GIC need the price of UBS stock to double just to break even. Given that the managers of GIC likely require stocks in their portfolio to earn a double-digit return when acquired, the implicit growth rate of UBS would have to be substantially higher to justify continuing to hold it. The question that GIC must address is whether this is likely to happen.

Adoboli’s rogue trading and the accompanying $2.3 billion loss inflicted on the shareholders of UBS are justifiably considered scandalous regardless of the apparent managerial lapses at UBS. Yet, GIC had paper losses of more than three times that amount from its investment in UBS stock (equivalent to a $1,560 loss for every man, woman, and child in Singapore at the time) and its loss was not considered controversial. The difference in the treatment of the two losses by the financial press and the public at large is puzzling. What’s the scarier scenario: Losing several billion dollars because one man, unpredictably, broke the law?15 Or losing several billion dollars because your sovereign wealth fund—run by highly paid professionals—lacks basic risk control?

Warren Buffet and EFH Bonds

Warren Buffet has established a phenomenal record of success as an investor, earning an incredible 19.8% return compounded annually for Berkshire Hathaway shareholders from the inception of the company in 1965 through calendar year 2011.16 Mr. Buffet is widely regarded as the quintessential value investor although some of his investment forays into commodities such as silver seem more like trades. Yet, investment and trading decision pitfalls affect every discretionary trader or investor including those with outstanding performance records such as Buffet. Examining an instance where Buffet exhibited decision pitfalls is instructive. Consider the following example.

In late 2007, Warren Buffett bought $2 billion worth of junk bonds of Energy Future Holdings, a power company. The ability of EFH to repay the bonds was linked to the price of natural gas. The higher the natural gas prices, the easier it would be for EFH to repay the debt. The price of natural gas rose sharply until mid-2008 and then fell even more sharply such that by the end of 2008, the price of natural gas was below the price when Buffet bought EFH bonds. The price of natural gas continued to fall although Buffet continued to hold the bonds. By 2012, the situation was so dire that Buffet noted that the EFH bond position could essentially become a total loss. Berkshire Hathaway had already written down over a billion dollars in previous years due to the failure of the trade.17

In his annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders dated February 25, 2012, Buffet made the following comments:

“...[EFH’s] ability to pay will soon be exhausted unless gas prices rise substantially....However things turn out, I totally miscalculated the gain/loss probabilities when I purchased the bonds.”18

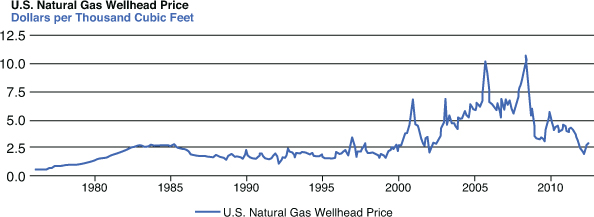

The behavior of natural gas wellhead prices in the U.S. since the 1970s is illustrated in Figure 11-1 from the U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Information Administration.

Figure 11-1. This chart depicts the behavior of natural gas wellhead prices from 1970s to the early 2010s.

Buffet’s decision to buy EFH bonds in late 2007 was a good trading decision. The price of natural gas soared as Buffet had anticipated it would. The price peaked around $14 per million BTUs (British Thermal Units) in mid-2008 but it started a long decline thereafter. Indeed, by the third quarter of 2008, the price of natural gas had fallen to the same level as where it stood when Buffet bought the bonds before falling even further later that year. Holding the bonds was no longer a good trading decision.

Natural gas continued to fall substantially below the price at which Buffet’s letter to shareholders warned of potentially further losses on the EFH bonds. By all accounts, Buffet chose to do nothing. EFH bonds are illiquid and a sale of Buffet’s entire position in EFH anytime would probably have depressed prices further. However, Buffet need not have sold his bonds in an illiquid market. He could have shorted natural gas futures or obtained credit default swaps on EFH to limit Berkshire Hathaway’s potential future losses on this investment.

Natural gas futures prices subsequently rose in 2012 although possibly not enough to ensure that the bonds would be fully repaid by EFH. Warren Buffet is certainly one of the world’s most successful value investors yet, as Buffet admitted in his annual letter, Berkshire Hathaway shareholders faced the very real and unnecessary prospect of having their entire investment in EFH bonds wiped out. Clearly, Buffet should have cut his losses short or hedged his risk exposure far earlier. His failure to do so is baffling but consistent with loss aversion. Ironically, for a value investor at least, technical analysis would have likely have gotten Buffet out of his EFH bond position sometime after natural gas futures prices started to fall in 2008 after a downtrend in natural gas futures prices became evident.

Trading Lessons

Losses are an integral part of the trading process. Every trader experiences losing trades. How a trader handles losses and losing trades plays a large role in determining that trader’s success. What lessons do the examples in this chapter suggest for traders?

Failure to Cut Losses Short

First and foremost is the need to follow the old trading adage of cutting your losses short. Like virtually every other rogue trader, Kweku Adoboli failed to do so at UBS. More surprisingly, the investment managers at GIC failed to do so with respect to its UBS stock position. Likewise, Buffet failed to do so with respect to Berkshire Hathaway’s EFH junk bond position. The danger of letting loss aversion affect trading decisions affects every discretionary trader. Traders have limited capital to deploy on their bets. Tying up capital in losing positions forecloses the opportunity of profitably investing capital elsewhere. In his interview in Market Wizards, Jim Rogers reinforces this point. “When we ran out of money, we would look at the portfolio and push out whatever appeared to be the least attractive item.”19 Now, the important thing to know about that quote is that Mr. Rogers uses the description of “least attractive” not “losing positions.” Even positions that made money were considered for liquidation, if a more attractive opportunity could be found.

Traders also have limited time to spend watching trades. Monitoring losing trades in the hope that the market turns around wastes time and capital that could be expended on selecting and investing in potential winners.

Failure to Let Profits Run

It is imperative to follow the entire adage quoted at the start of the chapter and let your profits run. If only a handful of trades account for most trading profits each year, as many highly successful traders contend, it is also critical to let your profits run. The profits from those few supertrades will more than offset the many (hopefully) small losses from other trades that looked promising but turned sour.

Trading profits rarely move in a straight line. Rather, they bounce up and down as the market fluctuates—putting at risk paper profits in the process. Legendary trader, Paul Tudor Jones II, has called this the “pain of gain.” It is tempting to take profits. Resisting doing so too early is difficult especially when profits are fluctuating as the market continues to move. However, it is also necessary if you are to let your profits run.

Consider the EFH bonds example. As it turned out, the price of natural gas futures hit a low around $1.90 in April 2012. It then rose sharply but still stood substantially below where Buffet acquired the EFH bonds in 2007. Does the subsequent rise in natural gas futures prices justify Buffet holding onto the EFH bonds? Not really. If you drive 90 mph around a blind curve on a narrow dangerous mountain road where the speed limit is 30 mph and survive, does it mean that you were driving safely because you didn’t drive off the cliff? The value of the EFH bond position was linked to the price of natural gas. If the price of natural gas rose, the bonds would likely be paid in full, and if the price of natural gas fell substantially below where Buffet got in, the bonds might be defaulted on. Buffet rode the price of natural gas up to over $14 per million BTUs and rode it down to around $1.90 per million BTUs. The price of natural gas fell an additional 25% after Buffet warned shareholders they might lose the entire value of the EFH bond investment. The post-April 2012 rise in natural gas prices wasn’t icing on the cake—it was lipstick on a pig. The subsequent rally in the price of natural gas after April 2012 illustrates another dangerous reality traders face: The market is an uneven taskmaster. The market doesn’t always punish those who let their losses grow—it sometimes rewards error. Sometimes, losers get lucky and the market bounces back and bails them out. The problem is that it doesn’t always do so—and the bad habit this chance creates encourages people to violate the fundamental rule of trading.

You should also be alert and avoid falling prey to the disposition effect by exiting winning positions too early while retaining losing positions. Sometimes the disposition effect arises from holding illiquid positions. Tiger Capital was the largest hedge fund in the world in 1998 with more than $20 billion under management. Its founder was Julian Robertson, another incredibly successful investor with an enviable performance record. Tiger Capital allowed its investors to withdraw their capital on a month’s notice. Although this is great from an investor’s perspective, it also exposed the fund to a run if many investors wanted their money back at the same time. The fund held a large short position in yen as well as a large long position in US Airways among other holdings in 1998. Sharp losses in the yen position in October 1998 triggered investor withdrawals. Meeting those withdrawals required selling fund assets to raise cash. Disposing of more liquid security positions is easier than disposing of less liquid ones. If this were done, it would have left the remaining portfolio heavily concentrated in less liquid securities which, in turn, could trigger more losses if they had to be sold to meet redemption requests. The fund was closed to the public in 1999.

Similarly, anchoring on the entry price as being unduly important causes many traders to bear potential risk of large losses for zero or minimal gains. Where you got in is not important after you are in a position. It is important where you can get out.

Failure to Listen to the Market

Losses are messages from the market telling you that you are wrong. Many traders fail to listen to the market. They fail to cut their losses short. They also fail to recognize potential trading signals in price changes. For instance, many market technicians and successful traders would argue that falling natural gas prices were a signal for likely further declines in natural gas futures prices in the EFH bond example. As the old trading adage goes: “The trend is your friend.” Other successful traders take a more fundamentalist approach. They might argue that falling natural gas prices were the result of low prices due to the greater supply of natural gas arising from fracking. Whether you believe that the past behavior of market prices contains a trading signal about the future direction of prices is up to you. The choice is yours. Perhaps, not surprisingly, Buffet—a quintessential value investor—chose to ignore that trading signal and retained his long EFH bond position.

Many successful traders reduce their trade size when they experience losses. Others stop trading altogether for a while if the losses are too large. The important point is that they listen to the market.

Sometimes, the relevant fundamental information is simply not available to most market participants. Jerry Parker, the founder of Chesapeake Capital and arguably the most successful of the “turtle” traders trained by legendary traders Richard Dennis and William Eckhardt, once said that the most important fundamental factor for the oil market in 1990 was Saddam Hussein’s decision to invade Kuwait.20 That decision caused the price of oil to explode to the upside. This was unknowable to most market participants except to Saddam and his close friends. Yet, the price of oil was trending up in the market before the invasion. This persuaded Jerry Parker and other trend followers to go long on crude oil even though the most important fundamental factor driving oil prices higher that year would not be known until after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait.

Confusing Trade Conviction with Trade Retention

Before you place a bet on the market, you should have a trading thesis and a trading plan in place. Many traders confuse their conviction in the correctness of a trading thesis with trade retention. Just because you are convinced that a trade is a good idea does not mean you should stay in the trade if you lose money. You need to listen to the market. Nor does the fact that a trade is losing money mean that the trading thesis is necessarily wrong. It might simply mean that the timing was wrong. You can always get back in. For instance, Paul Tudor Jones is justly famous for calling the stock market crash of October 1987 as well as the end of the Japanese stock market bubble in the late 1980s. What is less well-known is that Jones shorted the Japanese market several times and lost several times before his trading thesis was proven correct. Jones was successful because he limited his losses from his premature shorting of the Japanese stock market and let his profits run when the Japanese stock market started to fall.

Excessive Leverage

The sorry losses that many small FX traders experienced, recounted in the Barron’s news story excerpted previously in this chapter, illustrate the danger of excessive leverage especially when combined with tight stop-loss orders. The article noted that more than three-quarters of small traders lost money. In this instance, tight stop-loss orders work against highly leveraged small traders as noise in FX rates ensures that most traders will be stopped out at some point—hence the large fraction of traders who lose money, noted in the Barron’s story. This means for many small traders the sequence or timing of trading profits is extremely important to trader survival. Simply put, a small trader might be able to withstand a given dollar loss if the loss occurs after the trader has made substantial profits than if it occurs before. Many small traders simply cannot afford to have significant losses early in their trading career.

Trade Size Is Too Large

Closely related to the issue of excessive leverage is proper trade size. There is a desire by many people to trade size (i.e., trade large positions) out of machismo or other reasons. This might explain the fascination that many investors have with trading penny stocks where “large” positions in terms of the number of shares may be taken. Simply stated, many small traders trade positions that are too large given their limited capital. However, you don’t have to trade size in order to make a lot of money trading futures. You merely need to be right a fair amount of the time. A good rule of thumb is to trade in the size where you don’t worry about your position if you have losses.

The problem of trading too large a position arises even when massive leverage is not employed. Sometimes it arises in futures markets simply because of the minimum trade size is one contract so that even trading a one lot requires posting significant margin. Some successful traders limit the size of any one trade to 1% of capital in order to avoid having any one bet be too large.21 Many small traders are simply unable to do this. For instance, consider a small trader who has $10,000 of risk capital and wants to trade futures. Using the 1% rule, the trader should not risk more than $100 per futures trade. This is too small to even enter most futures markets. Indeed, the initial margin required for certain trades—like volatile stock index futures—could require him to post all of his risk capital (or more) to open a single contract futures position. This illustrates how limited capital frequently results in insufficient diversification and incorrect trade sizing.

Trading Too Frequently

Trading incurs transaction costs. Excessive transaction costs can—and will—substantially reduce trading profits. While it is important not to be frozen into positions to avoid incurring transaction costs, it is equally important not to trade excessively. One of the dangers of floor trading is that watching constantly changing prices can induce traders to trade in order to be doing something without good reason. A similar danger confronts day traders staring at a screen of constantly fluctuating prices. You should only trade when you have a reason to trade. Don’t trade simply because you can. Jim Rogers, never one to mince words, put it this way: “One of the best rules anybody can learn about investing is to do nothing, absolutely nothing, unless there is something to do.”22 Even low transaction costs add up if you trade too frequently.

Would You Rather Be Right or Rich?

Another danger that entraps traders is the desire to have the market demonstrate how smart they are. Many traders want the market to confirm that they are right and if the market suggests otherwise they are reluctant to exit their position until the market “sees the light.” If you want to make money, the market is always “right.” You might be convinced the market will move in one direction—but until it does, you’re wrong. And when it does, it is not you who are “right”; the market just happens to agree with you. All traders should ask themselves two simple questions: One is, “Why am I trading?” The correct answer is to make money. Another is, “Would I rather be rich or right?” Smart traders answer the former rather than the latter.

Failure to Have a Viable Trading Game Plan

Having the discipline to cut your losses short and let your profits run can be difficult, but discipline alone is not enough. Many traders do poorly because they lack a sound trading plan. They are simply trading on the fly. It is not clear that such traders know where their advantages lie. They might also miss opportunities when they arise by failing to recognize them as such.

Failure to Follow a Viable Trading Game Plan

Some traders may have a sound trading game plan but simply fail to follow it. As the old trading adage goes, “Plan your trade and trade your plan.” Don’t expect every trade to be a winner even if you have a sound idea. You must plan for losses, and the best way to plan for losses is deciding how you will minimize them.

Remaining in a Trade After the Reason for Entering the Trade No Longer Exists

Does the reason for entering the trade still exist? Buffet likely had a trading or investment thesis prior to acquiring EFH bonds. Although knowing the entire thought process that led Buffet to buy EFH junk bonds in late 2007 is not possible, it is likely that he thought he could pick up a relatively safe yield (the bonds were bought at a discount and reportedly yielded 11.2%) with minimal risk given Buffet’s expectation of what would happen to natural gas prices over the life of the bonds.23 To be sure, Buffet should have cut his losses short by liquidating the position after he started experiencing significant losses. However, he should also have exited the bond trade when the reason for being in the trade no longer existed. The sharp fall in natural gas prices in the second half of 2008 suggests that one of the principal reasons for getting into the trade no longer existed. Even the most profitable trades have a lifespan. When the market changes, your strategies need to adapt.

Again, this should not be interpreted as a criticism of Buffet’s investment prowess. A person would be foolish not to want to emulate his long-term investment performance. Rather, it illustrates how even highly successful investors can make costly mistakes.

Good Trades That Lose Money Versus Trading Badly

It is important to distinguish between a good trade that loses money, and trading poorly in general. For instance, a stock expected to increase from $25 to $30 per share with probability 0.5 or fall by $10 with probability 0.5 would be a bad trade because it has a negative expected value of –$2.50 (i.e., 0.5 × $5 + 0.5 × –$10). In contrast, a stock that is expected to increase from $25 to $75 per share with probability 0.5 or fall by $14 with probability 0.5 would be a good trade. The expected value is a positive $18 (that is, 0.5 × $50 + 0.5 × –$14) per share. The fact that the stock falls $14 to $11 per share instead of rising $50 to $75 per share does not mean that it was a bad trade. After all, there was a 50% chance that it would fall to $11 per share. You don’t expect to win all of the time. However, if the stock fell gradually to $11 per share and there were ample opportunities to get out, holding the position beyond a natural stop-loss point would be trading badly because you failed to cut your losses.

Another scenario also deserves mention: one in which the trader buys 1,000 shares of the stock at $25 per share, rides the stock down by $14, and then rides it back up and gets out early at $26; for example, when the stock has a 50% chance of going to $75. This is trading badly even though the trade was a good trade a priori. Sometimes, your worst trade can be one that you make money on. You made $1,000 ignoring transactions costs, but you also risked $14 to make $1. Would you take a bet where you make $1 if you’re right but lose $14 if you are wrong? The answer depends on the probability of either event happening. You might take the trade if the expected loss was lower than the expected gain. You certainly shouldn’t take the bet if each outcome is equally likely. Unfortunately, many traders take bets where they are willing to risk more than they make. Others convert potentially good trades into bad trades by trading badly. Under such circumstances, it is not surprising that these traders often blow up.

You need to evaluate potential trades before putting them on and evaluate actual trades after. Potential trades need to make sense at the onset for you to get in (that is, have positive expected profits). It is also important to recognize that all trades are probabilistic gambles when evaluating them after the fact. Although the odds should be in your favor before putting the trade on, you should not expect to win all the time. Ideally, ex post losing trades should all have been potentially good trades that turned out to losers as chance dictates. In practice, some ex post winning trades might have been bad trades because of how you traded. If you make trades where potential profits are cut short and excessive risk is taken it is only a matter of time before substantial losses occur. The lower the potential value from a trade, the more trading you have to do to exploit the perceived edge. This is a potential problem for small traders with limited capital. Can you ride out losing periods? Ideally, you want not only positive expected value trades but also trades that are skewed in your favor.

A trader learns the most from losing trades. Interpreting winning trades as confirmation that the trading thesis was correct is natural. That may or may not be the case. The truth is that sometimes factors beyond your control or, most importantly, beyond your knowledge, can determine the difference between a surge and a selloff. Of course, celebrating luck and attributing it as skill seems harmless when you’re making money. But make the same mistake twice, and you might get swamped the next time. Although losses are never welcomed, they have benefits. Losing trades force you to evaluate what went wrong. Learning from past mistakes is invaluable for avoiding them in the future. Although winning trades should prompt you to evaluate what went right, that is not always done. You need to evaluate all of your trades fairly and honestly in order to learn from your mistakes.

Endnotes

1. Baer, J. and F. Guerrera, “Goldman Faces Legal Bill of $3.4 bn.” Financial Times. March 2, 2011. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/fe935720-4434-11e0-931d-00144feab49a.html#axzz2AROtog6c.

2. Baer. J., “Goldman Beats Its Record for $100-m Plus Days.” Financial Times. March 2, 2010. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/88f2cee4-2598-11df-9bd3-00144feab49a.html#axzz2AROtog6c.

3. Thomas Peterffy World Federation of Exchanges Keynote Speech. October 12, 2010. http://www.futuresmag.com/2010/10/12/thomas-peterffy-world-federation-of-exchanges-keyn?page=2.

4. The study examines HFT firms in the e-mini S&P 500 stock index futures markets during August 2010. The HFT firms pursue a range of trading strategies. The authors report that HFT firms made $23 million in aggregate profits from that market alone and had Sharpe ratios ranging from 3 to 20 with a median Sharpe ratio of 4.5. Baron, M., J. Brogaard, and A. Kirilenko, “The Trading Profits of High Frequency Traders,” Princeton University working paper, November 2012.

5. Baron, M., J. Brogaard, and A. Kirilenko, “The Trading Profits of High Frequency Traders.” Princeton University working paper, November 2012.

6. Bary, A., “Pitfalls of the Currency Casino.” Barrons, April 9, 2011.

7. Ibid.

8. Trading derivative securities becomes a negative sum game when transaction costs are included.

9. Barber, B. and T. Odean, “Boys Will be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common Stock Investment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 116, No. 1, February 2001, pp. 261–292.

10. Liu, Y-J., C-L. Tsai, M-C. Wang, and N. Zhu, “House Money Effect: Evidence from Market Makers at Taiwan Futures Exchange.” April 2006. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=891564 or http://dx.doi.org/102139/ssrn.891564.

11. Kahneman, D. and A. Tversky, “Prospect theory: An analysis of decisions under risk.” Econometrica. Vol. 47 (2), 1979, pp. 263–291.

12. Jenkins, P., M. Murphy, B. Masters, and K. Burgess, “Singapore Fund Hits at UBS ‘Lapses.’” Financial Times. September 20, 2011. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/2f91e7a2-e380-11e0-8f47-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2AROtog6c.

13. Wu, Z. and N. Ismail, “GIC to Hold Citi, UBS Stakes for Many Years Tan Says.” Bloomberg News, January 30, 2011. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-01-30/gic-plans-to-hold-on-to-citigroup-ubs-stakes-for-many-years-tan-says.html.

14. Jenkins, P., M. Murphy, B. Masters, and K. Burgess, “Singapore Fund Hits at UBS ‘Lapses.’” Financial Times. September 20, 2011. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/2f91e7a2-e380-11e0-8f47-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2AROtog6c.

15. Kweku Adoboli was convicted of fraud and sentenced to seven years in prison in November 2012. Reuters News, “UBS Trader Jailed for Seven Years in $2.3 Billion Fraud.” November 20, 2012.

16. Buffet, W. Annual letter to shareholders. http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/letters.html.

17. Buhayar, N., “Buffet Says Energy Future Bet At Risk of Being Wiped Out.” Bloomberg News. February 27, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-02-27/buffett-says-energy-future-bond-bet-at-risk-of-being-wiped-out.html.

18. Buffett, W., Annual letter to shareholders, February 25, 2012.

19. Schwager, Jack, Market Wizards. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. 1989. Interview with James B. Rogers, Jr., pp. 305.

20. Richard Dennis and William Eckhardt called participants in their famous trading training program “turtles”—hence the term “turtle trader.”

21. It is also important to ensure that the trades are not highly correlated with each other. Otherwise, you do not obtain diversification benefit. Highly correlated trades essentially are one trade.

22. Schwager, Jack, Market Wizards. Interview with James B. Rogers, Jr., pp. 286.

23. On December 3, 2007, CNN Money reported that Buffett “purchased $1.1 billion of 10.25% bonds at 95 cents on the dollar to give Buffett an effective yield of 11.2%. And Berkshire bought $1 billion of 10.5% PIK-toggle bonds (bonds whose interest can be paid out in cash or more bonds) for 93 cents on the dollar, producing an effective yield of 11.8%.” [The bonds are scheduled to mature in November 2015.] Eavis, P., “Buffet Buys $2B in TXU bonds.” CNN Money, December 3, 2007. http://money.cnn.com/2007/12/02/news/companies/buffett.fortune/index.htm.