Chapter Sixteen. And finally ... how we got here

I want to finish the store section of the book with a look at the history of retail. It doesn’t properly fit here but I didn’t want to relegate it to an appendix either. This stuff is important and it will help you to be a better retailer. The lessons are all there for us.

Righty ho—I’m going to take us through the early years, up to somewhere around the 1950s. There are a few reasons for doing that—the first is to prove a really important point: Retailing is not about inventing new stuff.

Eh? “But you’ve gone on and on about ideas being the lifeblood of retailing and that ...”

That’s true, I have—here’s the thing: Ideas are of course vital, ideas are about change, improvement, and development, but they are rarely about coming up with things that no human has ever thought about before. You can be an innovative retailer by improving on existing ideas, by combining existing practices in radical new ways. But you don’t have to magically pluck brand-new “things” out of nowhere to be innovative and successful.

And this is a good thing. I’m going to show you over the course of this section that there have only really been four important inventions in retailing over the last 2200 years. This should be liberating for you—what I’m, in effect, saying is that you don’t have to reinvent the wheel to be innovative.

Rather than make you guess—I’ll give them to you for free. The four great inventions in retail are:

• c.200 BC—the creation of the first chain of stores (China)

• 17th century—catalog-based mail-order (Europe)

• 1852—the first true “department” store (France)

• 1915/16—self-service (U.S.)

That’s it. Yeah, maybe we’re overdue something else earth-shattering and new sometime soon; maybe it’ll be you that invents it, but if it’s not—that’s okay! It’s not vital to your success as a retailer. Oh, and if anyone is shouting “Idiot! Hammond’s missed out the Internet,” calm yourselves down: The Internet is just a development of catalog-based mail order and don’t kid yourself that it isn’t—it’s all distance selling.

On that point, right here in St. Albans where I’m happily typing away, there’s an excellent 19th-century analog to the current thinking among leading Internet players around becoming bricks-and-mortar retailers: On our original main street, there’s a beautiful white glass, brick, and iron-frame building. It looks like a cross between a massive greenhouse and a Victorian bath. Actually, it was built more than a hundred years ago as a showroom for the leading mail-order seed catalog of the time—it was a place where the seeds could be shown off as plants, where arrangements of flowers, trees, and shrubs could be suggested to customers and in which expert growers could pass on their tips. Isn’t that wonderful? You see—our retail past informs our retail present. The seed showroom is a Café Rouge now. Not sure what that says about the future of amazon.com!

I reckon there are two good reasons for giving you a bit of retail history: The first is to give you the reassurance that you’re not trying to invent something nobody has thought of before; the second is to show you that the challenges you face have all been solved before and that you can learn from those earlier experiences.

Actually, there’s a third and perhaps more personal reason for pulling together this brief history—and it’s that I believe retail is important and that the heroes of retail should be celebrated and their accomplishments enjoyed as we carve out our own retail successes.

The really early days

So, to the history. Our retail trade predates money—money comes later, having grown out of the need to mark retail debt in a consistent manner. What you do really is one of the oldest professions.

Markets

The first formal gatherings of retail outlets were barter-based markets. Within a community, specialist skills developed—one producer who had a skill, say, in stone implements would deliberately over-produce these so that he could swap his spares for food or clothing with specialists in those areas.

Retail chains

That brings us to the concept of the chain-store. It’s an interesting evolution—as the markets became more permanent and currency arrived, it made sense to construct a logistical infrastructure around those fixed points, the markets. Successful fixed-location shopkeepers recognized that growing their square footage (or square cubits, or whatever) and growing their potential customer-base represented excellent opportunities to make a little more profit. The answer was to open up another shop and have it operated by a family member. And would you believe, even back then there are records of these fledgling chain-store businesses using their improved volumes to leverage better terms from suppliers.

The earliest reasonable claim to “first retail chain” can be found in China over 2200 years ago and belongs to a retailer called Lo Kass. There is also a strong possibility that Roman shopkeepers may have a prior claim but only Lo Kass’s is actually documented. Roman excavations, across the empire, have shown that shops there were extraordinarily like small shops are today and given the excellent formal government, commercial, and transport infrastructures present even early-on in the Roman period, it’s pretty likely that chains emerged there. Lo Kass’s innovation, the thing that allowed him to extend his business, is that he was the first recorded retailer to employ shop managers from outside of his family.

Family to formal

Two things held back the small chains from making the leap to vast multiple retailers—the lack of non-familial trustworthy workers and audit systems to keep them so, and the lack of long-distance mechanised travel. It wasn’t until the Industrial Revolution had really hit, in the 19th century, that chains became much bigger and more widespread. A few of those pioneer chains still exist today.

Places of retail

Generally, retailing has always taken place at the heart of communities. Markets were central points in villages and inside the largest cities markets would spring up, centered on shared-interest locations—animal markets in one quarter, grain in another, cloth elsewhere, and so on.

Main streets, U.S.-style suburban strip-malls, and indoor town-center shopping malls (or centers) are the direct descendants of those community markets. The one major, late 20th century change to retail location history is the out-of-town shopping mall and the edge-of-town retail parks—we’ll talk about those a little more in a moment.

But the structure of malls themselves have been with us since the Romans. Dr. John Dawson (Professor of Retailing at Stirling University and a great retail brain) points out that the ruins of Trajan’s Market in Rome are remarkably similar to a modern urban mall. He goes on to mention that this particular market continued to operate in the same way throughout the Middle Ages and into modernity.

Later, much later, we get recognizably modern, though still very similar to Trajan’s Market, mall-style arcades including the Burlington Arcade in London, opened in 1819. The Arcade in Providence, Rhode Island introduced the concept to the United States in 1828. The larger Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan, Italy followed in the 1860s.

The move away from high streets

Suburban living, commuting, and the rise of the road and car has given rise to a move away from shopping on high streets. Throughout the 1990s and especially in the U.S., the center of retail has moved from the old high streets and into giant regional shopping malls and to massive stores located in retail parks on the edge of towns.

Lack of space has, to an extent, halted this move in Western Europe but even in spacious North America, something interesting is happening—main streets are thriving once more. Indeed main-street rents in the U.S. are increasing at an astonishing rate—rents tend to mirror commercial success and so are a useful barometer of location health.

It would appear that there is something fundamental about humans and shopping and doing so inside our communities (however superficial those communities may be). Fashion, food, entertainment, small-specialist, personal technology, personal services, and gift retailers will thrive again at the center of our communities and on our main streets—the added value of convenience, immediacy, and shopping in mixed, varied, and stimulating locations is rising.

Department stores

The development of department stores is important because it marks the first real, systematic, use of retail theater—and it’s that theater that has driven almost every single customer-facing innovation since. It is the absolute key component of modern format-planning and concept development. It is what sorts the mediocre from the fantastic.

Until 1852, shops were all small and specialist. That changed forever when Aristide Boucicaut and his wife Marguerite expanded their Parisian drapery store and began to also sell housewares and bed linen. They called their store Le Bon Marché and its inception marked the birth of the world’s first department store. The store launched on the back of innovations such as the promise to deliver “to homes as far as a horse can travel in Paris” and for the first time anywhere the store featured prices clearly written on all labels. The Boucicauts are even credited with the invention of modern stock management, where rotating merchandise and the staging of summer sales, winter sales, and blue-cross sales created constant change and excitement in the store.

Then in 1869, Bon Marché moved into stunning new purpose-built premises, designed in part by Gustave Eiffel, in the rue de Sèvres. Imagine how you might have felt the charge strike through you the first time you walked through the huge iron and glass doors and into its fabulous interior. Just imagine that thrill; stunning clothes, awe-inspiring furniture, drapery from all corners of the earth, sweets like you have never seen before, foodstuffs to make the mind boggle, and baffling new gadgets you cannot begin to fathom the workings of. You see assistants bustling here and there, catwalk displays of clothes, and dressed mannequins among showmen demonstrating the latest wonder. Every turn holds something new, a surprise, a wondrous assault on the senses. Imagine too how amazing it felt as you discovered that every department, as well as showing you awesome delights you’d never known existed, had lots of nice things in them that you could afford. Bon Marché changed its ranges constantly; new surprises were guaranteed all the time. It’s a product mix and stock management philosophy that worked then and still holds true today.

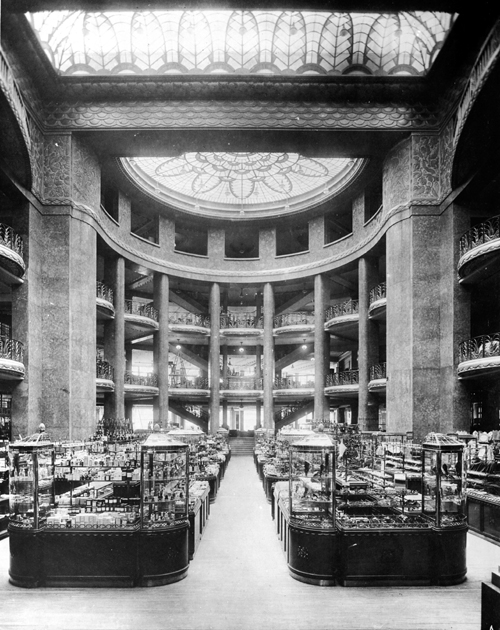

The Grands Magasins du Bon Marché was the world’s first department store. This photograph was taken in 1928.

Source: Royal Institute of British Architects Picture Archives

The concept of browsing a store was alien to the masses before 1852. It just was not a part of the contemporary ritual of shopping. Today browsers are essential to everyone from Wal-Mart to Harrods. That’s why we pack our stores with hot spots and why we change things so often. It’s all down to Bon Marché and their astonishing 19th-century Parisian innovations.

Well, that’s not entirely true. One other major, seismic, earthquake of change needed to happen and that was the development of self-service shopping. The established retail model, even within multi-department stores such as Bon Marché, was to keep products in cases, behind counters, or under glass—customers would be served by an assistant who would fetch customers” products for them.

Self-service

This all changed in 1915 when Albert Gerrard opened the Groceteria in Los Angeles, the first documented self-service store. The early part of the twentieth century was an extraordinarily competitive time in general-store retail in the U.S., but even in that white-heat environment, it took almost a year for another operator to copy the idea. And what a copy it was! Clarence Saunders, the founder of Tennessee-based Piggly Wiggly, built an entire business around self-service and then, the sly fellow, went and secured a patent on the concept (I’ve not been able to discover if that patent was ever enforced—I quite enjoy the thought of one of his long-lost relatives appearing out of the woodwork and suing all the grocers).

Saunders was something of a legendary loon and had begun construction of a pink marble mansion in Memphis, Tennessee when in 1932 the “bears” of Wall Street allegedly took him for a million dollars and rendered him personally bankrupt. The “Pink Palace” is now a museum, and it includes a walk-through model of the first Piggly Wiggly store, complete with 2¢ packets of Kellogg’s cornflakes and 8¢ cans of Campbell’s soup. It’s well worth a visit—the place shows you what a real retail innovation actually looks like.

And that’s where I’m going to leave the history for now and move on instead to the stories of some of the most important pioneers of our trade.

The retail kings

Say hello to the retail kings—these men are the true pioneers of your trade. They had no maps, instead forging their own routes through opportunity and adversity alike. There are a couple of sad endings, mind you—so be prepared for that.

Self-service as shown in Saunders” patent grant no. 1,242,872.

Source: US Patent Office

George Hartford and George Gilman—A&P (U.S.)

The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, better known as A&P, is the original American supermarket chain. The company was founded by George Hartford and George Gilman. By 1876, A&P had 67 stores, increasing to 1,000 by 1915. In the 1920s and 1930s, the company utterly dominated the American retail market, and by the end of that period, A&P was operating approximately 16,000 stores with combined revenue of $1 billion. That power led to the U.S. Congress passing several anti-predatory pricing laws—it’s interesting to see pressure on governments today to act in a similar manner in order to curb the practices of some of our most powerful supermarket chains.

That 1930s high has now, to a large extent, evaporated—A&P still trades today but from far fewer locations and it is far from the biggest retailer in the U.S. now.

A typical small A&P—this one is at L’Anse, Michigan—1950s.

Source: A&P Historical Society

In 1859, Gilman opened The Great American Tea Company, a corner shop, on Vesey Street in Lower Manhattan (the site today of Ground Zero). The store sold teas, coffees, spices, baking powder, condensed milk—all products that often came to America as ballast in the holds of clipper ships. The name change came in the 1870s when the company began to ship goods via the transcontinental railroad—with their broadened horizons, connecting “Atlantic” and “Pacific” must have seemed like an extraordinary achievement.

What marks out Hartford and Gilman from other retailers of the time is their voracious expansion ambition and achievement, and the way they overlaid that on a consistent format. They knew what customers wanted and delivered a store that met those needs—again and again, in location after location. Even today, the vast bulk of American retailers remain regionalized but the two Georges blitzed out those 16,000 nationwide, coast-to-coast, stores by 1937.

F.W. Woolworth—Woolworths (U.S.)

Franklin Winfield Woolworth (born on April 13, 1852, died on April 8, 1919) was the American merchant. Born in Rodman, New York, he was the founder of F.W. Woolworth Company, an operator of discount stores that eventually settled into the Big Idea of pricing merchandise at five and ten cents (making it a “five-and-dime” store). He pioneered the now-common practice of buying merchandise direct from manufacturers and was among the first retailers to fix prices on all items rather than haggle as was the prevailing tradition. Woolworth was also among the first retailers to recognize the potential in selling mass-produced products. Clever man, this Mr. Woolworth! F.W. was one of the first retailers to truly understand his customers—he recognized that this business is about consistency, choice, and democracy (good stuff, at the right price, for all).

Woolworth grew up on a farm but something sparked the retail bug in him pretty early on, and it was while working at a dry-goods store that he had his first great idea. He noticed that leftover items were often priced at five cents and placed on a table to get rid of them; he noted how much customers seemed to appreciate the five-cent table and a light went on in his brain ... Woolworth then borrowed $300 to open his own store in which all items were priced at five cents.

That first store, in Utica, New York, opened on February 22, 1879, and failed before the end of March. At his second store, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania (opened in April 1879), he adjusted the format by expanding the concept to include another range of merchandise priced at ten cents. This second range balanced the offer better and the Lancaster store became a big success. Woolworth and his brother, Charles Sumner Woolworth, solidified the template and then went on to open a large number of their five-and-dime stores.

The concept was widely copied, and five-and-dime stores were a fixture in the average American downtown for the first half of the 20th century, and they then later anchored suburban strip malls.

Always loving the grand gesture, in 1913 Woolworth built the Woolworth Building in New York City at a cost of $13.5 million (which he paid in cash). At the time, it was the tallest building in the world, at a height of 792 feet, or 241.4 meters. The Chrysler Building, with its craftily constructed spire, robbed Woolworth of that record the same year. Can you imagine the sheer balls of a man prepared to make a statement on the scale of the Woolworth Building? I love that—it’s madness, but it’s wonderful too.

The Woolworth Building in New York.

Source: AP/Press Association

As well as its American success, Woolworths extended across into lots of other countries—in the UK, “Woolies” became a fixture of everyday life. It provided ordinary families, like mine, with nice things at a very low price. The quality was reliable and the range mind-blowing: some 70,000 different lines by the start of the 1980s.

Woolworth died in April 1919 at the age of 66. At the time, his company owned more than 1,000 stores and was a $65 million corporation. Ten years earlier, he had opened his first British Woolworths, in Liverpool. He went on to personally open 50 UK stores before his death. Opening these stores himself, especially accounting for the time it took to travel between the U.S. and the UK back then, showed F.W.’s extraordinary commitment to consistency.

Stunningly, all that’s left of the original company, following a mass store-closure in 1997, is the Foot Locker chain (originally a Woolworths’ sub-brand). The South African, German, NZ, and large Australian Woolworths’ are very, very distant cousins, having all been independent of F.W. Woolworth and of each other for decades.

Ingvar Kamprad—IKEA (Sweden)

Ingvar Kamprad was born in Sweden on March 30, 1926 and is the founder of IKEA, having opened the first store in 1943. Not entirely sure why, but the earliness of that date surprises me every time I see it. Modern as it feels, IKEA has a long history, and it is thoroughly imbued with the benefits of evolution over a nice long timeline.

Ingvar developed his first business as a boy, selling matches to neighbors from his bicycle. He found that he could buy matches in bulk very cheaply from Stockholm, sell them individually at a low price, and still make a good profit. From matches, he expanded to selling fish, Christmas tree decorations, seeds, and later ballpoint pens and pencils. When Ingvar was 17, his father gave him a little cash for doing well at school. He used this cash to establish what has grown into IKEA.

Early IKEA was very much about opportunist retail, selling whatever it could, but the big growth came after Kamprad started to think systematically about selling furniture. His guiding philosophy came to be “A better life everyday for the majority of people.” I think he meant it too: IKEA is much more than the generation of profits. It offers good things to lots of people at a low cost and without class distinctions. It is accessible, exciting, and honest.

The story of why IKEA customers go into a warehouse area to pick up their furniture is a great illustration of why this company is a great one. In the early days of IKEA, you didn’t do that: A helper went and found your stuff for you. Then in 1965, they opened a big new store in Stockholm and on the first day, sales went crazy. There were more customers than the store could handle. Things were awful at the collection area. So the store manager made a judgement call: He opened up the warehouse and allowed customers to come in and find their own items. It worked so well that they tried it again another day, and the rest is history. In IKEA, that manager was recognized for having improved the way the store worked. Anywhere else and he’d have been reprimanded for breaking the rules.

A typical IKEA store.

Source: AP/Press Association/Herbert Proepper

In 1978, Kamprad wrote his seminal retail manifesto “Testament of a Furniture Dealer.” In it you read statements such as “to make mistakes is the privilege of the active person. Only while asleep does one make no mistakes” and “an idea without a price tag is unacceptable.” That character is strong in IKEA all over the world. It is so strong that it can be made to cross cultural borders. IKEA in Croydon is as recognisable in its IKEA-ness as IKEA in Gothenburg. I truly believe IKEA to be the best retail company to have ever opened its doors to a customer—it has become almost the sole source for furnishings for many households across the world, though there is some evidence now that competitors are emerging who can challenge IKEA.

There’s a word of caution here, and that’s the risk of ubiquity. There is a backlash beginning to rise against “IKEA style” in which a home furnished exclusively by IKEA is considered to be a bit cheap. My single criticism of IKEA is that the company hasn’t moved its design forward fast enough. We’ve had nearly a decade of the IKEA revolution in the UK and the products seem to be broadly similar now to the early days.

Sam Walton—Wal-Mart (U.S.)

Sam Walton, the founder of Wal-Mart, was a customer genius. More than that, in creating the world’s biggest company (not just the biggest retailer), he also showed how to create a consistency of culture that is truly gobsmacking. Every single member of the worldwide Wal-Mart team knows exactly what the company does, how it should do that, and why. The stores are packed with bargains, dependable value, and lots of things to make customers smile.

Wal-Mart is, however, facing pressures from home-grown challengers such as Target as well as encountering strong competitors in critical overseas markets (Aldi, for one, drove Wal-Mart out of Germany in 2006). Some of the Sam magic appears to be slipping away from the company (Walton died in 1992). U.S. employee unrest in particular is fast becoming a serious issue—it needs addressing before it’s too late, and before the goodwill that broadly does still exist within the workforce is further eroded.

Those are the clouds on the horizon—largely issues after Sam’s time—dealt with. Let’s get back to the good stuff: Sam Walton’s great legacy is everyday low pricing. As an early operator of franchised Ben Franklin five-and-dime stores, Walton made the unilateral decision to cut margins to the bone in a drive for volume. He chose everyday products on which to focus his most aggressive price discounting: toothpaste and ladies” pants were among his favorite and most successful choices. The simple observation that it was better to sell a ton of product at low margin than to sell a small volume at a high margin drove the almost unchallenged sixty years of Wal-Mart growth.

Sam Walton’s original store: now the Wal-Mart Visitor Center, Bentonville, Arkansas.

Source: Bobak Ha’Eri

Some of Walton’s most innovative ideas aren’t around promotion or price but relate to his work on cutting costs (savings that he then always passed on to customers). He was the first to offer his store managers a profit-share—essentially he said, “It’s your business; manage it as such and you will receive a share in the success.” Walton recognized that this would make his managers focus more on controllable costs, on taking advantage of product opportunities, and on reducing shrinkage. Another Walton innovation is the “greeter”—a member of staff standing in the entranceway to stores welcoming customers in. This system (which was actually introduced first by one of Walton’s managers as a temporary thing but recognized by Walton as a valuable permanent practice) dramatically cut customer theft at the same time as making arriving customers feel a little bit more important.

Though price became an absolute obsession for Walton, I don’t believe it was ever a greed thing. I’m convinced that driving the focus on price was Sam’s heartfelt belief that ordinary people should always get the best possible deal. It was an honest proposition that made him and his family an awful lot of money but that also reduced the cost of everyday items for hard-working honest citizens.

Wal-Mart has always attracted criticism from smaller retailers who accuse the company of exploiting their buying power to drive high-street and local retailers out of business. To an extent that’s true, and it’s why I believe that some measure of government control on monopoly and single-center retail power is sensible, but that’s only half the story. Many, not all but many, of those retailers who go bust in the wake of a Wal-Mart opening are doing so because they fail to offer their customers anything particularly special—there’s no added value there. Walton himself challenged small retailers to quit the bellyaching and “Work out what you can do that we can’t and then get really good at that thing and get really good at telling your customers about it.”

Quite right. That’s good advice—get busy living!

The Gordon Selfridge method—Selfridges & Co. (UK)

American Harry Gordon Selfridge opened a large store in London’s Oxford Street on March 15, 1909 and named it Selfridges (the current store, frontage included, is larger still, having been extended some time later). A clean-living dedicated man, Selfridge came alive when on the shop floor—he went from accountant to showman and is the true father of great retail theater. Indeed the resurgence of the once-moribund 1970s Selfridges is entirely down to another great retail entertainer—Vittorio Raddice. The key to Selfridges” early success was Gordon’s decision to move products out from behind the counters and to make them accessible to customers. He wanted shoppers to be able to touch, explore, and be excited by products (before an assistant then helped the customer to actually make the final selection—true self-service still being six years, and a continent, away).

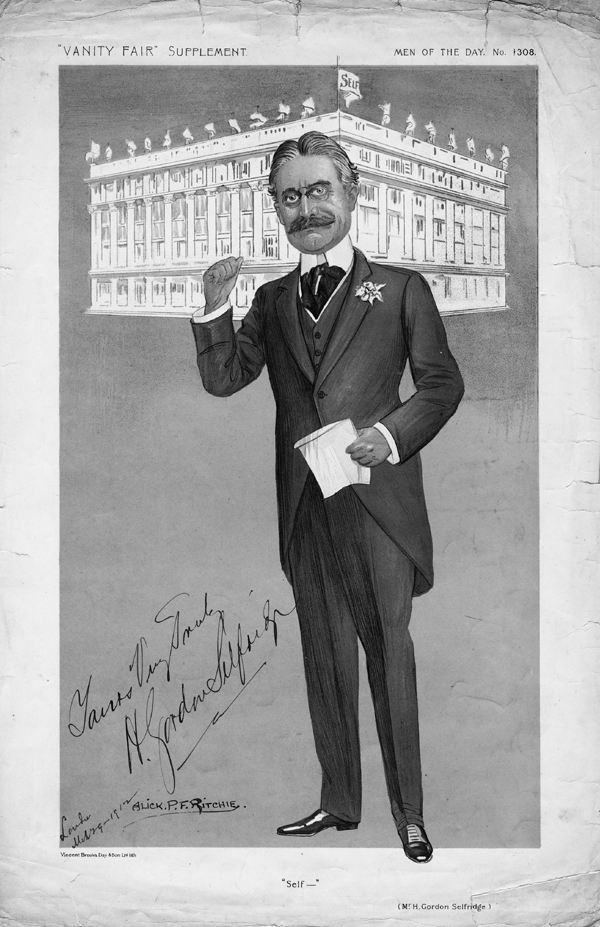

The man and his store, Vanity Fair—1911.

Source: National Portrait Gallery, London

A key component in the Selfridges format was staff behavior: He wanted them to be accessible but never aggressive, knowledgeable but never smug. He is the man most often credited with originating the phrase “The customer is always right”—an edict that permeated throughout the customer experience in-store. To be fair, I’m not sure we really know who first actually said that, but Gordo will do for now. Selfridge also recognized that he could make as much money delighting the less well off as from selling crazy curios to the rich. In this way, Selfridges was a democratizer—it was a store that welcomed and treated all customers equally. That simply had not happened before and is an important lesson in how to spread your appeal without diluting your brand.

Selfridge recognized the power of wonder to drive customer traffic and was always on the hunt for grand opportunities to demonstrate the world’s cutting edge. In 1909, after the first cross-Channel flight, Louis Blériot’s monoplane was exhibited in the store, where it was seen by 12,000 people. The first public demonstration of television was by John Logie Baird from the first floor of Selfridges in 1925. Just two examples in a long history—Raddice brought this sense of occasion back to the store with a series of powerful events and themes. Of late, these themed events haven’t quite felt as creative, passionate, or authentic as they did under Raddice. Selfridges in the period up to 2005 was the best store in the world, but it isn’t right now. I hope that changes.

Back to Gordon: He was born in Wisconsin on January 11, 1858. In 1879, he joined the retail firm of Field, Leiter and Company (which later became the legendary Marshall Field and Company). Over the next twenty-five years, Selfridge worked his way up the commercial ladder. He was appointed a junior partner and made a significant pot of capital for himself as well as successfully helping to manage the business.

His move to the UK was a huge gamble, really dramatic stuff, and came after he’d taken a holiday in London in 1906. He and Mrs. Selfridge had been utterly underwhelmed by the retail offerings in London and over the next few years, Selfridge plotted a return: this time as a retailer rather than a customer. In 1909, he came back to London with $400,000 capital and chose to invest it by building his own department store in what was then the unfashionable western end of Oxford Street.

I’m as much fascinated by the man as by his store—he was a great retail entertainer, understood inside and out the importance of surprise, discovery, delight, and “wow” but in his formal business dealings and in his private life, he was hugely restrained and at all times absolutely professional.

And then, in 1918, Mrs. Selfridge died.

Gordon went wild in the most splendid fashion. First off, he began to spend extravagantly, abandoned his teetotal tradition, and maintained a busy social life with lavish parties at his home in Lansdowne House in Berkeley Square. He bought Highcliffe Castle in Hampshire and promptly moved in a set of music-hall lovelies, triplet sisters as the story goes, and appears to have kept them as handy mistresses. It was almost as if Selfridge had finally given in to his own heady retail dream and decided to let it rule him.

But what goes up and all that: During the years of the Great Depression, Gordon watched his fortune evaporate—not helped by his gambling habit. In 1941, he was forced out of the Selfridges business, moved from his mansion, and in 1947 he died in absolute poverty at Putney in south-west London. The old man was regularly sighted, in tramp’s clothing, outside the Selfridges store toward the end—a sad end to a stunning life.