Reel Production

“Hollywood has always been a cage . . . a cage to catch our dreams.” —John Huston

While this chapter focuses solely on the physical side of production, the information it contains is useful for anyone in the industry (agents, managers, distributors, composers, attorneys, etc.). Because the more you understand about how a production office is set up and run and how a set functions, the more knowledgeable you’ll be about the business in general and the more effective you’ll be at dealing with the people who reside in production offices and on sets as they relate to you and your work. You’ll also come to realize that at one time or another, most facets of the industry intersect with one another.

The Production Office

For those working on a specific film or TV show, this is where it all starts. Casts and crews and vehicles and equipment don’t magically appear at a designated location site on a specific day at an exact time and start unloading, rigging, setting up, dressing, rehearsing, lighting and shooting unless a team of people seeing to every little detail makes it all possible. The “office” could be set up on a major studio lot, in a high-rise, in an old warehouse, a bungalow, a trailer, a mobile home, a hotel room or out of someone’s car; but it always serves the same purpose. It’s the driving force behind any production. Its significance and contributions are rarely fully recognized, and there is little correlation between how hard you work and the ratings or box office success of a film. Let’s face it. Who’s going to watch a movie or TV show and think to themselves, “Wow! Great production coordination on this one!” or “Gee, whiz. I loved the accounting in this movie!”

Coming from years of having set up, run and supervised production offices, I’ve witnessed the overwhelming feeling many rookies have upon walking into one for the first time. This is not something film schools generally prepare their students for, so let me give you an overview of how they’re set up and operate. If you’d like further information on this topic, I suggest you pick up a copy of my other book (if you don’t already have it), The Complete Film Production Handbook. In it you’ll find a much more detailed explanation of the production and accounting procedures that emanate from the production office (covering pre-production through wrap). Also included is a wide assortment of the most commonly used forms, checklists, releases, contracts and sample lists used to facilitate an entire production. If this is an area of the industry you’re interested in, knowing what the paperwork looks like will be invaluable to you. The book also contains a great Daily Office To Do List, which will give you a better idea of what a day as an office PA looks like.

The production office is the heart of a production. It’s the communications and operating center where, among other things . . .

- scheduling, budgeting and cost reporting take place.

- the crew is hired after their deals (salary plus extras that include guaranteed hours, screen credit, travel, housing, per diem, etc.) are negotiated.

- necessary services are lined up.

- deals are negotiated with vendors, and equipment, film and tape stock, vehicles, materials, supplies and catering are ordered.

- vital paperwork and information are generated and distributed.

- contracts, releases and agreements are processed.

- insurance coverage, completion bonds, clearances, license fees, location sites and permits are secured.

- cast perks are seen to and arrangements are made to get actors into Wardrobe and have them fitted for wigs and prosthetics.

- stunt work, aerial work and effects are planned.

- the look and colors of the film are decided and sets are designed.

- special requirements such as picture vehicles, animals, mockups, miniatures, boats, helicopters and models are purchased, rented, fabricated and/or rigged.

- travel and hotel accommodations are made for all show personnel working on distant location.

- shipping, customs and immigration matters pertaining to all foreign locations are handled.

- stages are secured, as are post production services and facilities.

. . . and where what seems like millions of details are managed, problems are solved and crew needs are met every day. (If you’ll refer to Chapter 4 under Production Management, you’ll find the delineation of responsibilities relating to the line producer, UPM, production supervisor and coordinator explained in more detail.)

Every show is set up a little differently. Sometimes an art department will choose to work at a different location to be closer to the set construction, the transportation department will work out of its own self-contained trailer, the wardrobe department will work out of a wardrobe house and the prop master will work out of a prop house. There are also shows where everything is set up at the same location. Generally, however, production offices house:

- at least one executive producer.

- at least one producer.

- the director.

- the production manager and/or production supervisor.

- the production coordinator.

- the accounting department–generally one to three (independently locking) offices, depending on the size of the accounting staff and the size of the offices.

- the location manager and one or two assistant location managers.

- two or three assistant directors and a couple of set PAs.

- the transportation department (coordinator, captain and a driver or two).

- the unit publicist (generally for two weeks before the start of principal photography).

- the art department (production designer, art director, set designer, set decorator, lead person, a set dresser or two, property master, assistant property master, art department coordinator and perhaps an art department PA).

- although not in the office all the time (and then only during prep) desks and phones are normally set up for both the stunt coordinator and director of photography (DP).

- a bullpen area for the assistant production coordinator, production secretary and at least two office PAs.

- an area for meetings.

- a kitchen or area that can be set up for craft service.

- a separate office or bullpen area for photocopying, faxing, assembling scripts, etc.

The line producer answers to the producer. The UPM and/or production supervisor answer to the line producer. The production coordinator answers to the UPM or supervisor. The assistant coordinator, production secretary and PAs work under the supervision of the production coordinator. The art director, set designer, set decorator, property master and art department coordinator report to the production designer. The entire accounting department works under the supervision of the production accountant. The location manager works closely with the director, production designer, producer and line producer. The first assistant director is chosen by the director and works closely with the director, line producer and UPM. The second assistant director is chosen by and reports to the first assistant director. And it’s the production coordinator who is primarily responsible for setting up and running the office.

Each office has a central information center (which is generally the reception area or a portion of a bullpen area manned by the APOC, production secretary and/or PAs), where departmental envelopes are hung; messages are posted; out-baskets are labeled and set out for Outgoing Mail, Overnight Delivery Packages, To The Set, and To The Studio (or parent company); deadlines for outgoing mail and overnight packages are posted; extra copies of crew lists, contact lists, the latest script changes, schedules, day-out-of-days, maps, request for pickup and delivery slips, etc. are stacked (or placed in hanging envelopes); start paperwork, time cards, I-9s and other payroll and accounting forms are available; a menu book and an office supply catalog are available to look through; local phone books and maps are kept; extra office supplies, mailing supplies and interoffice envelopes are stored; and waybills, fax cover sheets and other commonly used forms are available.

Because work days are so long (ranging from 10 to 15 hours a day, sometimes longer), it’s not uncommon for a production office staff to work in staggered shifts. It makes the hours a bit less brutal for some of the staff, and the office is covered at first call or at the start of the business day (whichever is first) through wrap or the close of the business day (whichever is last). Even when the crew call is not early in the morning, someone is available to set up the office for the coming day, be available to deal with vendors and accessible to prepping and rigging crew members who start early. And when shooting nights, many productions require coverage in the office through wrap.

For people who work all hours of the day and night, have little or no time to shop or cook and who these days are more healthconscious than ever, most production offices have a better stocked kitchen than you might have at home. The kitchen (or “craft service”) area is commonly stocked with an assortment of food, juices, snacks, fruit, etc., as well as a variety of headache remedies, antacids, cold medicine, vitamins and protein bars.

Accounting is a big part of any production office. This department is headed by the production accountant, who is essentially the guardian of the production’s purse strings. The department as a whole is responsible for opening vendor accounts; processing check requests and purchase orders; paying the production’s bills (accounts payable); processing payroll; dispersing petty cash; making sure studio or production company accounting procedures are being adhered to and that all State, Federal, union and contractual obligations are being met as they come due. They also play a major role in preparing insurance claims.

On their first day on a new show, crew members are given a packet of paperwork. This packet may include some or all of the following: a payroll start/close slip, a U.S. Immigration I-9 Form, a box rental inventory form, a blank deal memo form to be completed and approved by the UPM (the deal memo may also come from the production supervisor or coordinator), a set of safety procedures, a crew information sheet and a memo outlining the production’s accounting policies. This memo will generally cover procedures pertaining to payroll (paychecks are issued on the fourth work day of the following week, usually Thursday), box rental, vendor accounts, competitive bids, purchase orders, check requests, petty cash, production-owned assets, automobile allowances and mileage reimbursement.

During pre-production, while based out of the production office, members of the production team are scattered—scouting locations, having meetings, reading actors, working on script changes, supervising the building of sets, working on the schedule or budget, etc. This is a time when good communications are essential and when everyone needs to be aware of everything else going on around them. Once pre-production is over and principal photography begins, the director, assistant directors, DP and stunt coordinator work exclusively from the set. Members of the transportation, art, prop and location departments are in and out of the office, as is the producer, line producer, UPM and unit publicist. It’s a bit less crowded and noisy once shooting begins, but nonetheless busy.

Prep doesn’t stop when filming begins. As long as there is shooting to be done (and changes that occur), there are preparations to be made (and remade). Once principal photography begins, the goal of the UPM, assistant directors, production coordinator and the rest of the production staff is to keep one step ahead of everyone else by making sure sets are ready on time; special elements (e.g., equipment, prosthetics, picture cars, animals, etc.) are there when needed; filming progresses as smoothly as possible; unexpected problems are resolved quickly; the director and DP are getting the footage they envisioned; the studio is happy and being kept well-informed; the set remains harmonious and the show is running as scheduled and as budgeted.

Also during the shooting period, an assortment of paperwork is sent in from the set each night (waiting for the office staff when they arrive each morning). It’s copied, filed, acted upon and/or distributed as needed. The weather is closely monitored and cover sets are planned. A call is made to the lab each morning to make sure there are no problems with film sent in for processing the night before, and dailies are scheduled. Runs are coordinated between the set and the office throughout the day, and cars and drivers are arranged for actors whose deals include being picked up and driven home from the set. New equipment is continually being ordered, and equipment no longer needed is returned. There is constant communication with vendors, new purchase orders are generated and pickups and deliveries are scheduled. If on a distant or foreign location, on a road show that is constantly on the move, or if more than one unit is operating at one time from different locations, there is a continuum of travel and hotel arrangements to be made, new crew members starting and others wrapping, new locations to set up and others to strike, a voluminous amount of shipping to coordinate and travel movements to keep. Quantities of film or tape stock, office supplies, materials, expendables, etc. are constantly being monitored, inventoried and reordered as needed. Script and/or schedule changes are continually being generated and distributed. New cast members are starting all the time, necessitating new contracts and deal memos, wardrobe fittings, additions to the cast list, travel plans (if necessary), etc. Call sheets are delivered, faxed or e-mailed in from the set toward the end of each shooting day and photocopied. Maps and safety bulletins are attached, and “sides” are prepared for the next day’s shoot and sent back to the set with the call sheets. And in between a steady flow of problem solving and budget balancing, UPMs and production supervisors make their way through stacks of POs, check requests, invoices and time cards in need of approval. All in all, the production office represents a fine-tuned operation that keeps the production running smoothly and continuously advancing toward completion. While what goes on behind the scenes is rarely heard about, it’s a facet of the filmmaking process that should never be underestimated.

A Reel Set

Walking onto a real set on a real movie or TV show is very different than the set of a student film. First of all, your crew is much larger. And second, there are unwritten protocols and rules of behavior that you wouldn’t necessarily know unless someone were to tell you or you happened to learn them the hard way.

Deciding what to shoot each day starts with what’s reflected in the shooting schedule. Adjustments are made to accommodate changing weather conditions, availabilities of certain locations or pieces of special equipment or the possibility that the show is running behind or ahead of schedule. Once the first assistant director, director and line producer agree with what’s to constitute a day’s work, it’s reflected onto a call sheet and distributed the evening before.

Actors and stunt performers are given work calls to accommodate the time it takes them to get through wardrobe, hair, makeup and prosthetics, and crew members are likewise given call times to accommodate the amount of prep time they need. More time is always needed when shooting in a new location. Less set-up time is required when returning to a long-standing set on a sound stage or other interior location. When shooting on a distant location, drive time to and from the set is also factored in to the work day.

Each day is different. Sometimes a succession of scenes is completed, sometimes just portions of one scene. Much will depend on what type of show it is, the schedule and budget and how complicated any particular scene is. A one-page scene of two people sitting at a table talking is going to take a lot less time to shoot than a one-page scene full of car crashes, stunts and explosions. One complicated scene (such as one on a battlefield) could take several days to accomplish (as well as multiple cameras and second units).Much will also depend on the amount of coverage any one scene is given. Low-budget films and TV shows with inflexible schedules and budgets don’t have as much latitude when it comes to creative lighting and camera moves.

Let’s just say you have a scene in which several people are sitting around a table talking and having dinner. Coverage would normally begin with a master shot, often achieved with a wideangle lens to encompass everyone who’s in the scene. Subsequent coverage might include two-shots, close-ups, over-the-shoulder shots and high- or low-angle shots. If the table is outside on a rooftop, the director might want an aerial shot (captured via helicopter). The more coverage the director is able to get, the more footage the editor has to work with. Every time the camera is moved, however, another set up is created, and lights, equipment and sometimes flats (walls) must be moved to accommodate the shot. If the entire scene is played out in the master, then each subsequent set up represents a portion of that scene, sometimes requiring many takes until the director is ready to move on. Multiple set ups and takes equate to a lot of waiting around, and those new to working on a set are always surprised at how slowly things move (especially on features).

The same basic sequence of events occurs over and over again throughout the day. They are:

- Rehearse: The director works with the actors as they go over their lines and get a sense of the scene.

- Block: Decisions are made as to where the actors will be standing, how the scene will be lit and where the camera(s) will be placed. Once finalized, the principal actors are dismissed (to deal with wardrobe, hair, makeup, prosthetic fittings, etc., or to just relax and go over their lines in their dressing rooms). At this point, the stand-ins are brought in for the purpose of lighting.

- Light: The DP and gaffer are now in charge of lighting the set as per the director’s wishes.

- Shoot: Once the set is lit, the stand-ins are dismissed and the principal actors are brought back in to shoot. (It is the second assistant director’s responsibility to make sure the actors are ready once the set is ready for them.)

If you’re going to be working as a set PA, here are some things you should know.

- Wear comfortable (and quiet) shoes.

- Have extra clothing in your car and backpack to cover changes in weather (extra sweatshirt, T-shirt, socks, gloves, boots, hat, warm jacket, rain gear); also sunglasses, sunscreen and a bandanna.

- Consider getting yourself a walkie-talkie belt (which can usually be found at an Army-Navy surplus store or a sporting goods store) or a waist pack to accommodate a walkie-talkie, cell phone and pager. It’ll make it a lot easier for you to lug that stuff around all day.

- Keep a three-ring binder with the schedule, day-out-of-days, crew list, pager/cell phone list, contact list and the script (with all the latest script revisions). Most ADs and set PAs also carry legal-size metal clipboards with a hinge on the left side. They refer to it as “my tin.” The outside is flat and great for writing notes. The inside is used to store call sheets, production reports and a few basic supplies. They can be purchased at specialty stationery stores or online.

- Your basic set supplies, or “kit,” should contain pens, pencils, white-out (the roll-on type is the best), a small flashlight, note paper or a mini notebook and reduced versions of the crew list, one-liner, cast list, cell phone/pager list, contact list, etc. They won’t all fit inside your clipboard, but you might get them into a fanny pack or work belt; and they should be carried around with you at all times.

- As a PA or trainee, you’ll report to the 2nd AD.

- Read the back of a call sheet, learn crew job titles and how many of each are going to be on the set

- Learn basic crew terminology: what is a DP (and who is he/she)? What is a gaffer? A best boy? If you’re told to get a grip, he’s probably the guy with the hammer sticking out of his backpocket; the electrician is probably the guy with a pair of gloves sticking out of his back pocket and clothespins on his sleeves, etc.

- Learn the names of the cast and crew as quickly as possible.

- Learn where each department is located (wardrobe, makeup, camera, etc.) so you can find people quickly.

- Know the phone number for the stage or location.

- Learn the paperwork as soon as possible.

- Start familiarizing yourself with union and guild guidelines.

- Learn military time (or keep a chart with you for easy reference).

- When you’re asked to do something, do it quickly and report back that it’s done. Don’t make your supervisor have to come find you and ask if it’s done.

- Always give the impression that whatever you’ve been asked to do is going to get done quickly. If for some reason you can’t accommodate a request, let your supervisor know immediately, so other arrangements can be made. (There is always a sense of urgency on a set, and delays are costly!)

- Show deference to strangers on the set, as you never know who they are.

- Have a sense of when to be quiet, even when quiet hasn’t specifically been called for. If in doubt, be quiet.

- If you see something that might be hazardous, mention it to your supervisor.

- If you see someone smoking, ask them to please stop, and if they don’t, advise your supervisor.

- Never introduce yourself to a director or an actor because you’re a big fan and/or to ask for an autograph. You’ll meet them soon enough in the course of your job; don’t bother them unnecessarily.

- Stay out of the director’s and actors’ line of vision. Stay behind the camera.

- Never take still photos on a set unless you get prior permission from the Director of Photography.

- Never sit down (except at lunch or to do paperwork).

- Be the last to take lunch—after the actors and entire crew.

- Keep your conversations on the walkie/talkie short and to the point (or go to another walkie channel).

- If you have nothing to do and have permission from your supervisor, help the crew out whenever possible. (Again, never stand around with nothing to do.)

Getting Into the DGA

If you think you might like to pursue a career as a DGA assistant director, there are a few different ways to get into the guild. While not the easiest to qualify for, the best route is via one of the official training programs.

- Headquartered on the West Coast is the Directors Guild—Producer Training Plan (Assistant Directors Training Program), which was established in 1965 by the Directors Guild of America and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. To qualify for this program, you must first apply to take the yearly test. Applications are submitted by November 5th, and the test is given in late January. To qualify to take the test, you must be at least 21 years of age, have employment eligibility to work in the United States, a high school diploma and at least one of the following: (1) a Bachelor’s or Associate’s degree from an accredited college or university, (2) certification that you are a currently enrolled student who will complete your coursework and graduate with a Bachelor’s or Associate’s degree no later than June 24th, (3) written proof that you attained at least the level of E-5 in a branch of the U.S. military service, or (4) two years (520 actual work days) of full-time paid employment in film or TV (or its part-time equivalent). You may also use a combination of college credits and work experience to meet the eligibility requirements.

The test is offered in Los Angeles and Chicago and eligible applicants must pay a nonrefundable testing fee of approximately $75. One to two thousand individuals take the test each year. Of those, half generally do well enough to move on to what’s called the “assessment center,” where group interviews are held. Half of those who make it through the group interviews are asked to come in for individual interviews. Of those, 15 to 20 individuals are chosen to become part of the 400-day program that includeson-the-job training and a series of curriculum-based seminars. To find out more about the program or to download a test application, go online to www.trainingplan.org. The number of the DGPTP is 818/386-2545.

- The two-year New York Assistant Directors Training Program accepts, on average, 250 to 300 applicants each year, and five to seven are accepted into the program. Applicants must be U.S. citizens or permanent residents. A four-year degree and some industry experience are recommended but not essential. The written part of the test is offered in late February. Preliminary interviews are held in April, and final interviews are held in May. For more information on New York’s program, call their office at 212/397-0930 or check it out on the web at www.dgatrainingprogram.org/geninfr.htm.

- You are allowed to work third area on a union show until you’ve accumulated 120 work days. Once your days (and all required substantiation) has been accumulated, you can apply to be placed on the Third Area Qualification List, which is administered by DGA Contract Administration (DGACA). The DGACA will inform you if everything is in order, and a copy of that letter along with your application package will be passed on to the DGA. The Guild then has 30 days in which to agree or object to your application. If they have no objection, you are then placed on the Qualification List, and it’s up to you whether to join the DGA.

Third area is considered anywhere outside of the Southern California area which extends from San Luis Obispo to the U.S.-Mexican border and the New York triborough area. For a second assistant director, first assistant director, unit production manager or associate director/technical coordinator, 75% of 120 required days must be spent with the actual shooting company and no more than 25% may be spent in prep or office work. For directors, 78 of the 120 days shall have been in directing the actual shooting of film or tape. Likewise, stage managers or associate directors in the live and tape television industry employed 120 days or six years in the nationwide feed of television motion pictures are also eligible to be placed on the Qualification List. For further information on applying for the Third Area Qualification List, check out the DGACA website at www.dgaca.org.

- On the West Coast, to be placed on the Basic Qualification List, you would have to work on non-union shows for a total of 400 days as a 2nd AD, 1st AD, UPM, technical coordinator or associate director/technical coordinator. The Basic List is also administered by the DGACA. For ADs and UPMs, no more than 25% of those days may be spent in prep and 75% must be spent with the actual shooting company. For directors, at least 260 days shall have been in directing the actual shooting of film or tape. Stage managers or associate directors in the live and taped television industry must be employed 400 days or six years in the nationwide feed of television motion pictures.

- The New York-based DGA Commercials Contract Administration administers the Commercials Qualifications List, which covers the New York and Southern California areas as well as third area. Check out their website (www.dga-cql.org) for specific requirements for placement on the Commercials Qualifications List as a 2nd AD. Any individual who has been placed as a Commercial 2nd AD is eligible for “interchange” to the New York Basic List in the same category. To be eligible to “interchange” to the Southern California Basic List as a 2nd AD, you will need to upgrade to a Commercial 1st AD. This requires documentation of having worked at least 150 freelance days as a 2nd AD, with no fewer than 75 days of work on commercial productions.

- If you are working as an AD or UPM on a non-union film that becomes a signatory during the course of the production or are hired early on before a new production entity signs a DGA contract, you may work on the show as an “incumbent.” Should you become an incumbent, you will be in a position to join the DGA, but you’ll also find yourself in kind of a Catch-22. Once this show has wrapped, you cannot work on other DGA shows until you’ve fulfilled all your days, nor can you go back to working non-union shows to get your days. If you don’t have your days by the end of that first show, you have to get the remainder by working other shows for that particular company, working third area or by being an incumbent for other companies.

When it comes to actual DGA membership, initiation fees, dues, etc. are handled directly through the Guild. Be sure to check out their website for further membership information. It’s www.dga.org.

The Production Team

I know this gets confusing, but the production team (as opposed to the studio’s creative team whose members are given production titles) refers to “physical” production and those who physically prepare for and supervise the shoot of any given project. The Producers Guild of America defines the producing team as those responsible for the art, craft and science of production in the entertainment industry.

Physical production encompasses the positions most newcomers are aware of, but at the same time, they’re not always sure who does what. Even people who have been in the business for a while are sometimes unclear as to exactly who performs which functions on any given show. While some duties can only be performed by individuals who occupy specific positions and others can be accomplished by a number of different people, depending on the parameters of the project, there is no doubt that production requires team effort.

From where I sit, there is a core group that comprises the production team, and they are, the:

- Producers

- Director

- Line Producer

- Unit Production Manager

- Production Supervisor

- First Assistant Director

- Second Assistant Director

- Production Accountant

- Production Coordinator

Think of casting directors, location managers, post production coordinators and the studio and network executives assigned to your show as auxiliary team members.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t always happen this way; but the ideal is a team that works well together and where members understand and support each other’s boundaries and goals. In other words, should you find yourself with a producer and director (or any other members of the team) who don’t see eye to eye and can’t find enough common ground to get along—you’re cooked! An adversarial relationship from within this group becomes a problem for everyone. On the other hand, efforts made to collaborate on shared common objectives, enhanced by a mutual respect for one another, will inspire the cooperation and loyalty of the cast and crew, will be helpful in promoting a pleasant working environment and will favorably influence your schedule and budget. Once you have a viable script and either a studio deal or outside financing in place, this is the group of people who will take these elements and make them into a movie. The mood and temperament of the production team is going to permeate the entire project and affect everything and everyone involved. It therefore behooves you to put together the very best team you can.

Based on the six phases of any film–development, pre-production, production, post production, distribution and exhibition–some members are involved in more than two phases, but everyone on the team is involved in both pre-production and production. These phases represent the putting together and coming together of all elements necessary to shoot a show.

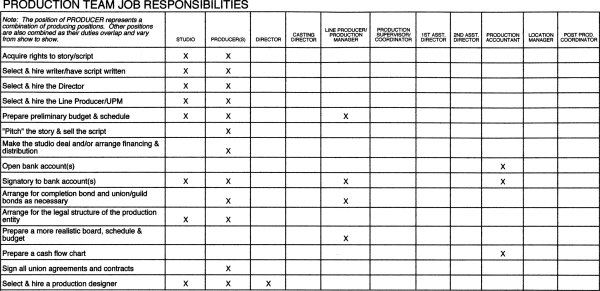

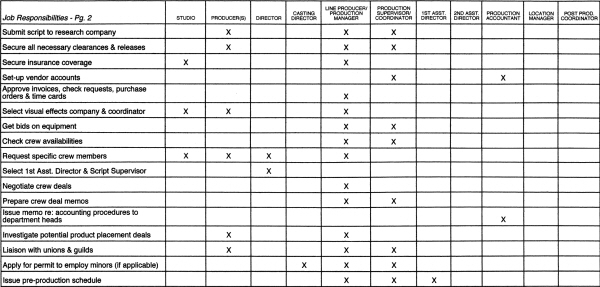

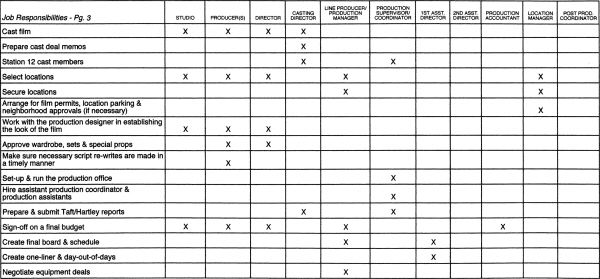

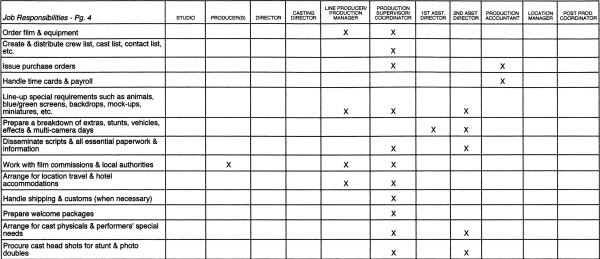

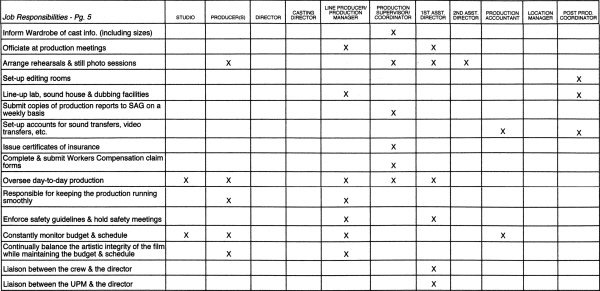

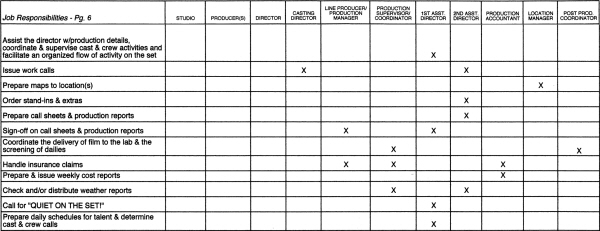

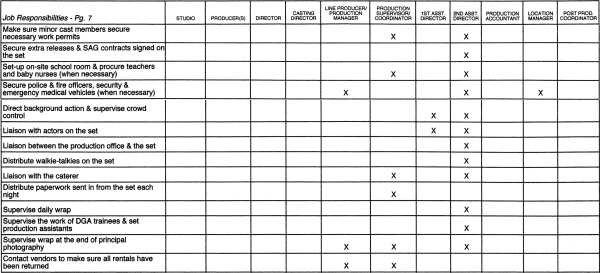

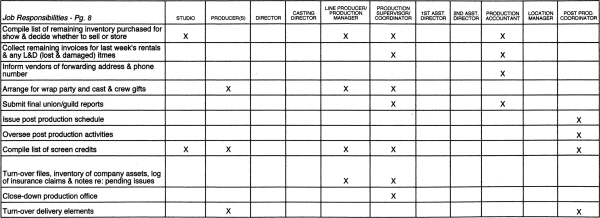

The job responsibilities attributed to members of the production team will vary depending on whether the film is being made for television, cable, theatrical or Internet release; and on the project’s budget, schedule, union status and location. The following is a chart that illustrates job functions (that range from acquiring the rights to a story or script through the submission of delivery elements) and indicates which position or positions generally fulfill those responsibilities. For a more in-depth interpretation of how a production team functions, primarily from the perspective of the production manager and first assistant director, I recommend a book entitled The Film Director’s Team by Alain Silver & Elizabeth Ward (Silman-James Press).