CHAPTER 2

Finding and Evaluating a Story

▲ Vigil for Teen Crash Victim. A videojournalist has to stay current. The day after a Cheney High School student died in a two-vehicle collision, mourners gathered for a candlelight vigil near the scene of the accident. There was something about the short news brief on his paper’s website that caught the producer’s eye. ![]()

(Photo by Colin Mulvany, Spokesman-Review)

This symbol indicates when to go to the Videojournalism website for either links to more information or to a story cited in the text. Each reference will be listed according to chapter and page number. Links to stories will include their titles and, when available, images corresponding to those in the book. Bookmark the following URL, and you’re all set to go: http://www.kobreguide.com/content/videojournalism.

Now that you’ve learned what makes great storytelling, how do you actually go about finding possible stories and evaluating their potential for your video and multimedia journalism projects? Sometimes a story comes from the videojournalist’s own experience. Sometimes it comes from talking with other people. Story leads can grow out of news assignments. Following are some other possible sources for stories.

WHERE TO DISCOVER STORY IDEAS

Stories are all around you, but how do you get started? Watch for trends that might include shifts in the public’s buying preferences, changes in lifestyles, or a technology revolution in an industry. For example, a news story about a new smart phone might result in a trend story that looks all the ways smart phones have changed how people communicate.

A trend doesn’t start in one day; it occurs gradually over time. Gary Coronado, a staffer for the Palm Beach Post, read an opinion piece about the trend for Central American immigrants to jump on trains for a free ride to the United States. He filed the clipping and later pitched the story to his editor. His dramatic multimedia story is called “Train Jumping.”

Read the Paper or The News Online

“Having worked at the same newspaper for 22 years,” says Colin Mulvany, a multimedia producer at the Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington, “I feel pretty connected to my community. I know what is happening in my town. I know what people are talking about and this helps lead me to good stories.

▼ Train Jumping. From a newspaper story, the producer learned about the trend of Central American migrants hopping trains to reach the United States. ![]()

(Photo by Gary Coronado/Palm Beach Post)

“Many times at my newspaper, word editors would pitch stories about major community events. My approach is to think less about an event and more about the people at the event. Personalizing a big, sprawling story with compelling characters will make your video stories come alive.

“In order to find multimedia story possibilities, I troll the newspaper’s lists of upcoming stories (a.k.a. story budget). The deciding factor on whether to commit to doing a video or audio slideshow versus doing a still photo depends on two things: (1) is there a strong central character in the story and (2) is it visual? One without the other is usually a no-go.

“I’m always searching for that elusive emotional gem. When we package a daily video with a print story, I look for ways to tell the story a little differently than what the print reporter is doing. Instead of thinking broad, I think defined. That can mean focusing on just one or two subjects out of six the reporter might have talked to.

“Nearly all global stories have local impact,” says Mulvany. “Nearly every small town has a soldier in the wars in Afghanistan or Iraq. Every rural county has families with unemployed parents due to the struggling economy.

“Reporting and producing stories like these to your local audience will help put global events into better perspective, and when you do so with a strong narrative and powerful characters, you can really draw in your audience and make a powerful connection with them.”

Mulvany’s advice on finding stories: “Find time every day to read and listen to news and information that you can use for story ideas in your work. Listen to NPR, read national and international publications like the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. Watch a variety of television news programs to stay informed. Write down your ideas and follow them up with research.”

Craigslist, Classified Ads, and Social Media

Today, online classifieds like Craigslist, and social media outlets like Facebook are exploding in popularity. We all know by now that social media is a handy tool for keeping up with friends and family, but that’s not all its only use. It also allows us stay abreast of what’s going on locally. Make use of your connections to people who are more in the know than you are. Participate in discussions. Check out those sites daily and maintain your connections by interacting. Social media sites make excellent sources for story ideas and subjects. You may find that an acquaintance is aware of a strawberry festival or a baton twirling contest, a beauty pageant or an important political gathering going on in your town. If you’re always at the ready, you can quickly run out and cover it. Use tools like Facebook and Twitter to stay in touch. They might indeed lead you to some unexpectedly terrific stories.

ICU: Los Angeles Connections. Craigslist, the Internet’s global classified website, can be a gold mine of story ideas. The Los Angeles Times produced an entire series of stories that were found in the “Missed Connections” section of Craigslist. In this section of the site, people describe a situation about how they almost met someone they had encountered. But, for a variety of reasons, they didn’t get the opportunity to actually meet that person. The stories about these missed opportunities—called ICU, as in I See You—feature love, lust, loss, and intrigue and span the emotional spectrum from heartfelt to hilarious.

Videojournalist Katy Newton, the project’s producer, came up with the idea. “I had a friend who was going to Trader Joe’s for weeks at the same time hoping to see a guy again whom she hoped might be the perfect match for her, based on the vegetables he was choosing,” Newton explains. “I had never heard of Craigslist’s Missed Connections, but when I checked it out the next day, my first reaction was that many listings in that section of Craigslist are real human interest stories. They contain drama, and they’re all set up with engaging characters who have a pressing need they feel must be fulfilled.”

The fact that all of these stories had built-in compelling narratives was just what Newton was looking for to apply to a regularly running series of online video stories.

▲ ICU: Los Angeles Connections. ![]()

▲ ICU: Nice Guy I Hit with My Car. The videojournalist found her subjects by searching the Missed Connections section of Craigslist. ![]()

(Produced by Katy Newton)

After Newton came up with the idea and made a successful pitch to her editors, she began the process of weeding through hundreds of ads a week, getting up early each day to read the posts on Missed Connections. “Just by the way they wrote the ad,” Newton says, “I could tell which ones would be good storytellers, and so I would email about a dozen people a day and hear back from a couple and narrow my choice down from there after talking on the phone.”

“These narratives that unfold from Missed Connections have perfect built-in arcs,” says Katy Newton. For example, one of Newton’s stories is about a woman who hits a guy on a bike with her car.

First she sets up a normal day. A woman is driving in to get gas and then—wham!—she hits something or someone with her car. This moment creates speculation in the audience’s mind. What or whom did she hit? Then, she inserts an amusing comment. The audience is taken quite by surprise when the woman says, “I thought I might have hit a baby.” Then the truth is revealed. The driver has hit a man on a bike. One might expect the man to be angry or sustain a severe injury. The two characters might end up hating one another. Instead, Newton explains, the story has a twist. The guy isn’t angry with the woman. Instead, he is worried about her. This comes as a welcome shock—not only to the woman, but also to the viewer. In a happy instant, the perpetrator, the woman has found the type of guy she has been looking for—someone who values the welfare of others before his own. Who wouldn’t want to meet someone like that? Of course, the resolution of the story isn’t that the couple lives happily ever after but that the main character finds the type of man she has been dreaming of meeting. The quirky part is that he disappears. Now, the young woman is left to wonder. She has no idea how to contact this man of her dreams again. Hence the original reason for her posting on Craigslist’s Missed Connections.

So the story is set up with a need; there is a twist; the need is satisfied; and a problem is resolved. Newton explains that though each of the 52 stories produced in ICU that year were on different subjects, they all more or less followed this same arc.

Looking back, Newton tells us that the series was a success. Her audience wrote in frequently with positive feedback.

Obviously, the success of this series of stories was due to the fact that all people inherently want to connect and find love. Looking for love is a universal theme. So we can all empathize with the subjects’ personal tales of missed connections.

Aside from Craigslist, make sure to check out blogs and websites on any and all topics you can think of. At this writing, there are over a 125 million blogs, 500 million Facebook users, and 255 million websites on the Internet. A search on Bing, Google, or Yahoo! on any subject that comes to mind will surely bring up a healthy list of story possibilities. You can research a topic internationally, nationally, or right in your own backyard. Learn from the experts how to hone in on your topics with more efficient searches. ![]()

▶ A Team Without a Home. Scott Strazzante’s path to find this story of a soccer team consisting of homeless players is a great example of finding for stories by keeping your ears, eyes, and—most important—your mind open. ![]()

(Scott Strazzante, Chicago Tribune)

Often you can even check facts for your story with a web search. Or you might be able to find contacts and potential subjects to interview that way. The Cision Survey found 89 percent of journalists turn to blogs for story research, 65 percent go to social networking sites such as Facebook and LinkedIn, 61 percent use Wikipedia, and 52 percent go to microblogging services such as Twitter. ![]()

Bulletin Boards

Locating usable stories requires constant observation. Never walk past a bulletin board or utility pole covered in flyers again without at least scanning the notices. There is probably at least one story on every utility pole. Pick up neighborhood flyers and subscribe to email lists from clubs and organizations to find out what’s going on. Often you can translate a group’s activity into a lead for a genuinely compelling story.

Listen for Offhand Comments

Take your eyes off your smart phone for a sec. Stories can be lurking in the environment through which you move every day. Stay awake and alert at all times in order to be ready for them.

Scott Strazzante, a photojournalist at the Chicago Tribune, says that his antennae are always up. “I find that while I’m shooting routine assignments, I’m simultaneously listening to people talking. I’m reading blurbs that are in every little neighborhood publication, forever fishing for ideas. In simple stories that my newspaper thinks are just a brief, I might find a great narrative angle to make a powerful audio slide-show from. I never discount even a passing idea.”

For example, Strazzante was sent to a nearby community to make a portrait of a family living in a homeless shelter for a Christmas gift-giving story. The night manager of the shelter gave him a quick half-hour tour and Strazzante made his portraits. “On my way out, the manager said to me, ‘Have you ever heard of homeless soccer? There’s something called the Homeless Soccer World Cup, and there’s no team in Illinois yet, but we’re starting one here.’ So of course my story lightbulb went off big time,” Strazzante says.

Strazzante spent the next several months following the team from the Illinois shelter, shooting photos, recording audio interviews, and capturing ambient sound. He says it was a perfect narrative of a sports story. Would they succeed or would they fail? They trained and sweated and ran their legs off. Of course, there were ups and downs in their season, including many losses and even the death of an assistant coach. But the team members struggled on, all the while dealing with their own personal issues of homelessness.

Cross the Tracks

To hunt down the best stories, do one thing everyday that makes you a little uncomfortable. Go to unfamiliar neighborhoods and attend meetings of groups that are completely new to you. When you go, hand out business cards. Sit down and chat with the folks present. Ask people what’s been going on in their lives and communities.

What is important to them now?

What or who would make for an interesting story?

What stories are the news media not covering in their lives?

What are the local controversies?

Who are the characters in the community?

The standouts? The misfits? The community leaders?

“A Sunday morning without assignments led me to a small Baptist church that I had never been to,” recalls this writer, who was working for the Roanoke Times at the time. “While there, I photographed a middle-aged woman who cared for a handful of elderly women during the service. Some of those women were widows, others had husbands with duties at the front of the church, and so the women had to sit alone.”

▲ Age of Uncertainty. Sylvia Coleman lifts a cup of wine to help Hattie Brown take communion. The photographer suggested a feature story on this woman who assists her fellow church members. But a colleague encouraged him to think more broadly about what this lady did—caring for elderly people in general. ![]()

(Photo by Josh Meltzer, Roanoke Times)

“Sylvia Coleman helped the older women turn to the correct pages in the Bible. She told them when to stand and sit and when to drink their communion wine. Many of the elderly women suffered from Alzheimer’s or dementia.

“The next week, while chatting with colleague Beth Macy, I suggested a feature story on this woman who helps her fellow church members. Macy encouraged me to think more broadly about what this lady did, about caring for the elderly. With a few weeks of brainstorming with our editors and experts on aging, we developed a plan for a nine-part series on people who voluntarily care for the elderly. The news peg was that our community in western Virginia was experiencing huge growth in its elderly population. This new demographic raised the question: ‘Who will care for this rapidly growing population?’”

The photos and audio gathered at the church that morning never even made it into the final project. But they did become the spark for a series that personally and intimately related to members of the community who come from different backgrounds. The project, called “Age of Uncertainty,” was made up of nine video stories, photo galleries, and interactive elements. And, accidentally, it was born out of a random Sunday morning foray to an unfamiliar church across the tracks from this writer’s usual haunts. ![]()

Localize and Personalize Large Issues of the Day

Think of the biggest stories in the news going on right now. They might be playing out in Washington, D.C., and appearing on national news, or perhaps they are unfolding in the largest immigrant communities. But no matter where they are occurring, chances are they are affecting people who live in your community or town.

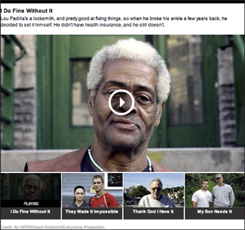

The health care reform debate filled the news for endless weeks. Most of the video reports on television focused on town hall meetings and congressional debates, both important events related to the issue. Robert Krulwich produced “Four Stories on Health Care” for National Public Radio Online (the NPR website also features multimedia and video stories) that put faces on the news and presented four unique different viewpoints and situations of real Americans who will be affected by health care reform.

In one story, a locksmith reveals that he has never needed health insurance and doesn’t want it. In another story, a man is thankful that he had insurance after a near-death accident at his home.

▲ A Locksmith’s Tale and Other Health Care Stories. To tell the complicated story of health care for NPR Online, Krulwich and Hoffman zeroed in on the personal tales of a few individuals. ![]()

(Robert Krulwich and Will Hoffman, NPR Online)

These unique stories of different individuals do keep the audience centered on the large issues of health care and insurance. But they go further by presenting personal stories that help the audience to better identify with the broader issues. Furthermore, because the audience experiences these stories through single characters, there is a better chance viewers will be engaged and the stories absorbed in their entirety.

Stories About the Past

Telling a complete story about the past using still pictures only, though certainly not impossible, can be a challenge. However, using multimedia complete with interviews, graphics or archival footage makes the job of recounting a tale about the past much more manageable. Writers have always loved to tell narrative stories about the past. But photographers often struggled with what they should photograph when a story had already happened. Now, with unlimited access to the tools of multimedia, the subjects of our videos can take an audience back in time just as writers do for the written word.

Ben Montgomery, Waveney Ann Moore, and photographer Edmund Fountain from the St. Petersburg Times produced a story called “For Their Own Good” about the abuse suffered 50 years earlier at the Florida School for Boys. The men tell haunting stories of abuse and punishment and the lingering effects of that trauma.

◀ For Their Own Good. A story about the past will require creative visuals because documenting the story with video is often no longer possible. Portraits, landscapes, and still-life photography as well as other creative visual approaches will help to cover a strong audio story. ![]()

(Ben Montgomery, Waveney Ann Moore, and photographer Edmund Fountain/St Petersburg Times)

Portraits of the men and landscapes of the now-abandoned school accompany the powerful video interviews.

Long-Term Projects

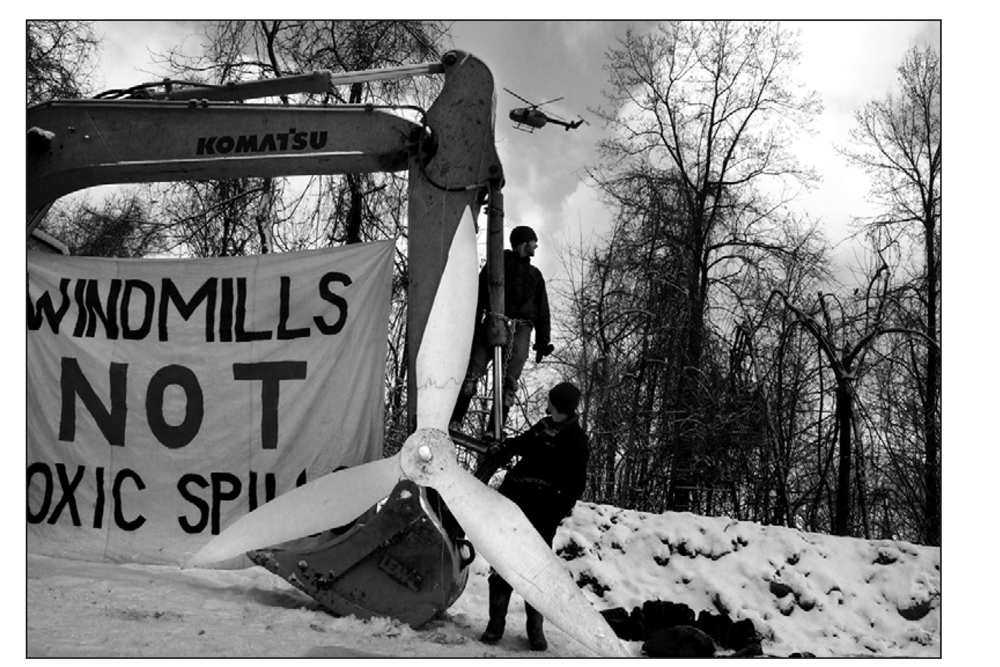

In 2003, Chad Stevens, now an assistant professor at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, traveled with students from Western Kentucky University for a spring break workshop (the Appalachian Cultural Project) to the Eastern Kentucky town of Whitesburg, deep in the heart of coal mining country. While working there with a few dozen students, he first learned of a mining process called mountaintop removal, in which coal companies blast the tops off mountains to extract coal without having to mine underground. “I had grown up in Kentucky and had never heard of the practice,” Stevens says, “but when we went to see it first hand, I was changed forever.” Stevens had read a book called Lost Mountain. That book became the source for his master’s thesis at Ohio University. Stevens says, “The genesis of the project was to do a visual version of this book with still images only, which would symbolize the transition of a mountain through this drastic process.”

Tat initial spark has now spanned into a seven-year (and counting) project that evolved into a film project that Stevens continues to shoot to this day.

While shooting, Stevens has simultaneously been raising funds intensely. There are many grants available to photographers and filmmakers, some more competitive and lucrative than others. Stevens has won a few and lost others. But, along the way, a few freelance licensing projects have come his way. He never expected these lucky breaks, he says, which have fortunately helped to fund his project.

▲ A Thousand Little Cuts. In one of the more extreme acts of civil disobedience on Kayford Mountain, an activist poses as a crucified Jesus on the edge of the Arch Coal mountaintop removal coal mine.

The first nonviolent protest on Coal River Mountain brought attention to the campaign to build a wind farm. Five protesters, including Rory McIlmoil, left, and Matt Noer-pel, chain themselves to an excavator on a mountaintop removal preparation site. Chad Stevens, the photographer, has been working on the project for more than seven years. ![]()

(Photos by Chad Stevens)

“I’ve licensed blast footage to a broad spectrum from Al Jazeera to the BBC and most recently Spike Lee’s film If God Is Willing and Da Creek Don’t Rise,” he says. “Without foreseeing or even trying, I became the go-to person for mountaintop removal footage.”

Though Stevens considers that the risk of taking on a long-term personal project is personally and financially daunting, he feels strongly that “there is something in the universe that helps us when we risk. Risk is usually rewarded in one way or another.”

Some of the most important and influential photographic and documentary projects have emerged from personal interests. These kinds of projects are neither easy nor cheap. But if you can find a steady support network for both financial sponsorship and editing assistance, you can pursue issues that are important to you. Your conviction and enthusiasm for your own personal subjects will often be reflected in a highly successful result.

Keep a Journal

Richard Koci Hernandez, former multimedia journalist at the San Jose Mercury News, has volumes of journals that he uses to take notes, record inspirations and thoughts, and make sketches and plans for future and ongoing projects. “If you really study some of the most creative artists and storytellers and writers or musicians, many of them have kept meticulous journals—everyone from Edison to Picasso—all at different levels and in different styles, but it’s been critical to their success, and I’ve found that to be true for me, too,” Hernandez says.

“Keep the journal with you all the time,” he says. “You’ve got to be disciplined to write in it regularly. Even while I was working for the San Jose Mercury News, I would drive down a street a hundred times and all of a sudden I would see a store or a person and something would hit me on that 101st time for a potential story or a type font that I liked in my next project, and if I hadn’t had the means and the notion to jot it down, I would’ve forgotten it. Now, more than ever, it’s important to ‘journal’ because we’re so inundated with info on the Web.”

Hernandez says he finds his journals most useful when suffering from a creative block in editing. “I’ll just pull out my journals to remind me of ideas and—boom!—problem solved. All this stuff we think we’ll remember will inevitably slip through the cracks under the pressures of daily life.”

▲ Journal. Richard Koci Hernandez’s journal of ideas that he kept when he worked for the San Jose Mercury News.

Hernandez also uses the Internet to find inspiration. “In addition to a small physical journal you can use social networking, bookmarks and RSS (real simple syndication) feeds to keep up with and share work that inspires you,” he says. “Google Reader is a great way to subscribe to blogs and websites that you want to keep in touch with. I visit my Google reader list most mornings to see what’s new when looking for inspiration. Furthermore, use Facebook, Twitter, and multimedia sites like vimeo.com to follow the work of artists and journalists you admire.”

STORY FINDING TIPS FROM REPORTER BETH MACY

When the Roanoke Times ace reporter Beth Macy thinks she might be onto a good issue story, she often meets an expert for coffee to feel out the story and to start gathering a list of potential subjects and a plan of action. Macy is always on the prowl for ideas, pulling out her calendar as she browses bulletin boards or has a conversation with a public relations representative from a relevant organization. A friendly meeting in person over coffee or tea will often yield Macy more contacts, names and numbers for a variety of stories than she could ever hoped to have gotten over the phone. “When you’re genuinely curious about the world, there isn’t a topic that, with the right amount of probing and tweaking, can’t make a great story,” Macy says. Macy’s story-finding tips:

• Be nosy. Sniffing out a good story is like being paid to get a graduate degree in stuff you’re interested in.

• Get out of the office.

• Public relations representatives can actually be great sources, if you prod them enough.

• Pay attention to your own life. Do other people experience the things that are going on with you?

• Reserve judgment. Don’t knock down an idea before you give it a chance to mature a bit.

• Be alert. It’s the old boyfriend theory. The only time you find a boyfriend is when you’re not looking for one.

• Read the walls—bulletin boards, ads, and posters for upcoming events.

• Listen to what your friends are talking about; eavesdrop on strangers.

• Collaborate. Find reporters, photographers, producers, and/or editors you like to work with, can collaborate with and trust.

• Trust your gut. If I find myself talking to my husband about someone, or find myself ruminating about something, there just might be a story there.

• Read and take copious notes.

FINDING SUBJECTS

The subjects in a story are often dictated by the nature of the piece. Some stories are about a particular person or family, whereas others are about an issue for which you will choose topics that exemplify the issue you are focusing on. The themes that you choose must draw the audience into the story and make them feel a part of it for the entire time. You don’t want viewers to feel like mere observers—outsiders looking in. If you can hunt down truly engaging subject matter, you’ll have a better chance of creating an excellent piece of work.

Three Necessary Keys Before Selecting a Subject

Pamela Chen, a senior communications coordinator in photography and multimedia at the Open Society Foundations says, “Often, we encounter the story of a person whose life journey encapsulates the metaphor for the bigger picture issue. But in order to produce a multimedia story, we need to know:

• First, is this person actively engaged on the issue and doing work that is visually dynamic?

• Second, do we have the access necessary to recordthis action? Is the person willing to show their face and record their voice for the camera?

• Third, will they allow someone to follow them around in their daily life for an extended period of time?

“These questions are about action, access, and time. They are all three key to the eventual outcome. If this trio of crucial criteria cannot be met, then we must seek another way to tell the story.”

Chat with Your Potential Subject

While preparing to shoot a video story at an event, Evelio Contreras, a video photographer at the Washington Post, says he’ll often casually chat with people at the event before shooting. This accomplishes two things. First, it allows him to understand the story better, and second, he can hold informal pre-interviews to determine whom he might want to interview for the piece he is about to shoot.

“I never go where I’m expected or assigned to go. I don’t want to be where the main story is, but rather I choose to be on the sidelines. The main story is very often over-populated with people who aren’t looking for stories but rather sound bites. They are not looking for a dialogue or a conversation.

“I’m looking to have a conversation with someone so that I can hang out with them … so that they’ll be loose and relaxed and be themselves. I want to be able to hear someone sound as if they actually want to be talking to me.”

Contreras says he looks for people who are quirky or have something different about them. If they make a lot of hand gestures, he says, he’ll see that as a sign of someone who might be a character in the story. “I’m looking for passion in their eyes.”

Contreras tries to establish himself as a documenter up front so that he can start a one-on-one conversation as soon as possible. He says, “I’m not interested in a hodge-podge of voices. I see that as overload to the audience. And it can often be a gimmick. I feel that interaction with one character at a time is more deliberate storytelling. You really have to suss out the tale you want to tell ahead of time.”

Searching for Great Characters

Tim Broekema, a professor at Western Kentucky University, says, “You can’t sit at your desk and speculate: ‘Hmmmh. I wonder where that character might be lurking.’ Captivating characters appear to you when you’re out in the field asking questions. Allow characters to come and go in and out of your life until you find the just right one. Too many beginning videographers get stuck. They settle for a character they think is ‘good enough.’ But ‘good enough’ isn’t going to cut it. The chances of finding a great speaker who is also visually pertinent to your topic are few. Characters who grab and hold the viewers’ attention are pivotal. So the process of characters earch is vitally important. Magnetic characters are just plain gifts from God.”

Leads from Public Radio International (PRI) and National Public Radio (NPR). In This American Life’s “Going Down in History” video story for Public Radio International’s (PRI’s) website, Ira Glass and his visual reporting team attend a high school portrait day to talk about how a single image taken that day for the yearbook—a photo which really doesn’t represent much of anything about you—is the image that becomes your permanent historical record. In this story, Ira Glass shows the audience dozens of high school yearbook portraits. He then selects a half a dozen students to interview about this odd situation.

At the portrait day for class pictures, Glass gets students to open up while reflecting on the idea of the permanent portrait captured their yearbook. The students discuss boyfriends, gossip, and what they regret doing in their past. They are fantastic subjects and they certainly weren’t picked at random. They’re all great talkers. They aren’t shy and they obviously enjoy elaborating on Glass’s comments and questions. ![]()

Many excellent examples of character-told pieces can be heard on National Public Radio’s (NPR) weekly feature StoryCorps. StoryCorps actually is a nonprofit devoted to recording people’s stories of their lives. The group uses a radio booth housed in an Airstream trailer that travels about the country and invites volunteers to interview a friend or chat with a relative or simply to recount a personal story. ![]()

For more well produced stories on radio, check out This American Life and Radiolab. ![]()

Look for an Extrovert

On the topic of finding a subject, Darren Durlach from station WBFF-TV in Baltimore observes, “Hopefully a great character is someone who is dynamic, open, and unafraid to say what they think. Viewers generally care more about those extroverted types. Of course everyone we talk to each day is different. But I have learned to use my gut to look for ‘real’ people. The more sincere they are about what they say, the more their message shines out through the television screen. I just jump right in and ask almost everyone who walks by a question or two off camera to put out feelers or lead me in the right direction. Oh … and we always try to avoid making leading characters out of public information officers or stiff people in suits because that usually takes us out of the realm of sincerity.”

In Marlo Poras’s full-length film “Run Granny Run,” the lead character, Doris Haddock, speaks eloquently about her motivations to run for U.S. senator of Vermont in her mid-90s.

She takes the audience through her entire range of emotions throughout the story, and is open, well spoken, and often very funny as she attempts to break many stereotypes of the modern-day politician.

Characters who are the most “interview-able” are not camera-shy. They even like the camera. They speak clearly and with appealing detail about their experiences. Additionally, you will find that the more interviewable people are, the more they will offer when you ask questions. It’s almost as if they can sense what you’re looking for.

◀ Run Granny Run. Doris Haddock, in her mid-90s, a true character, explains her motivations to run for U.S. senator of Vermont. ![]()

(Film by Marlo Poras)

There is a category of people who are overinterviewed. Their message often sounds a bit memorized, like a sound bite. Politicians and public figures often fall into this category. If you’re faced with interviewing such a person, plan ahead and ask unusual questions— questions that won’t elicit a sound-bite response. Hark back to 90-year-old politician Doris “Granny D” Haddock. That feisty woman politician certainly does not fall into your typical sound-bite category.

EVALUATING THE STORY’S POTENTIAL

All stories, regardless of the medium, should consider the following: strong characters, narrative tension, a take-away point to remember, strong visual impact, emotional engagement, broad appeal, narrow focus, cooperative subjects, and a reasonable deadline. It wouldn’t be a bad idea to answer these questions: what does the story say about the human condition? Will it be a visually exciting story? Will the story have broad audience appeal? What emotions does this particular story tap into in order to engage your viewers?

Strong Characters?

Strong characters in your online stories are like the friend that everyone wants to hang out with. They are funny, compelling, and interesting to listen to. They entertain us, enlighten us, and keep the focus on their story.

We have seen all kinds of stories covering the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, from battle-field action to recovery, families at home, and even analyses of money spent during the war. Craig Walker’s Pulitzer Prize–winning story “Ian Fisher: American Soldier,” for the Denver Post, contains all of these elements, including a strong lead character. In a ten-part video story, we follow the path of an average U.S. soldier, Ian Fisher, as he signs up for the military, trains, heads to battle, and returns. The narrative is powerful, with honest interviews with Fisher and his mother and father throughout the piece.

◀ Ian Fisher: American Soldier.

▼ Ian Fisher cradles his injured elbow during processing into the Army at Fort Benning, Georgia. Though he later has a change of heart, he sees a possibility only two days after arriving, to escape enlistment. From his first day in fatigues through his days driving a Humvee in Iraq, military life often doesn’t mesh with his expectations. Sometimes the structure of the Army and the demands of training for war clash with the freedom he shared with his outside friends. ![]()

(Photos by Craig Walker, The Denver Post)

▲ Ian braces for his crossed-rifes pin, signifying his completion of training. Drill sergeant Eldridge holds the pin in place and prepares to secure it with a fst. “I hit him square on the chest,” Eldridge says. “He had two holes, and blood dripping down from each—‘blood rifes.’” A sergeant closes the ceremony: “You are now the guardian of freedom and the American way of life! A warrior!”

◂ As his team prepares to secure a room during a training drill, Ian is the first man in a four-man stack. Echo Company is deep into three days of urban-combat exercises. Drill sergeant Tommy Beauchamp has a lot of experience to share: he served one tour of duty in Afghanistan and two in Iraq.

The story arc for Walker’s piece is classic. It’s chronological and follows Fisher through a major change in his life with twists and turns, ups and downs, and a variety of small setbacks and successes that keep the audience’s attention. Furthermore, this story is playing out in every town and city in America where soldiers have been sent abroad to war, so it helps to explain who these soldiers are and what their individual stories might be, by telling it through the eyes of one soldier.

Walker begins the story as Fisher graduates from high school and follows him for 27 months through his return. And Fisher is a perfect character. Completely open and compelling, he offers insight into his situation and serves as one representative for the more than 100,000 soldiers serving in Iraq. The narrative has ups and downs and twists and turns that serve to keep an audience hooked, wanting to know what happens to the young unsung hero soldier.

▲ Ian shows his frustration during a counseling session with Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Weisensel. For the second time, Ian returned late from a weekend home. Now he has turned himself in for a drug problem. In the days to follow, Ian’s failure to cooperate puts him in danger of getting kicked out of the Army. Instead, the commander assigns him to a new platoon and drops him in rank. It’s a demotion. But it is a fresh start.

Finally, Ian’s story has relevance to current events, is reflective of how Fisher feels about being at war, why he joins and how it is to return. This impactful piece puts a face on a large issue in what is probably the biggest story in this period of American history. It is a personal and intimate look at one of the most important stories of the decade.

Narrative Tension?

Michael Nichols and J. Michael Fay’s story “Ivory Wars,” featured on MediaStorm, is the story of efforts to protect elephants, often hunted for their ivory tusks, both inside and outside of national parks in Chad. Though the issue of poaching certainly is important on its own, it still needs a narrative thread to which audiences can attach themselves. The filmmakers and producers found a narrative thread within the general report on a national park. They zeroed in on one elephant named Annie whom the researchers collared to track as she moved both in and outside of the park.

▶ Ivory Wars: Last Stand in Zakouma. A story with narrative tension about poaching. ![]()

(Photos by Michael Nichols)

▲ Three days after Ian’s return from Iraq, he and Devin apply for a marriage license. The couple are married an hour later in a quiet courtroom. Driving away, Ian turns down the music. “Ya know, everyone gets counseled in Iraq that life is not going to be like your fantasy when you get back home,” he says. “Well, I’m checking this off my fantasy list.”

Now their story, which is still about the issue of poaching and protection of natural resources, contained a chase that followed both the researchers tracking Annie’s every move and the poachers who aim to kill her just as she exits the safety of the Zakouma National Park’s boundary. Annie wanders here, and the tension builds. Then she goes there, and the action grows even more compelling as she continues to move throughout the region in search of water. Finally, we learn that Annie has been shot by poachers.

The tension, not knowing what will happen to Annie, is precisely what keeps an audience’s attention. The narrative tension that the storytellers create and build upon as the story progresses is the kind of vehicle that carries an audience through a piece.

Cooperative Subject?

One of the obstacles that can make or break a story is whether your subjects are in tune with your need to finish the story. This is one obstacle you must work out early. Your characters may simply see you as a photographer who wants to take a portrait and be done with it. But in fact, you have plans to hang around with them for the long term. You want to do several interviews and organize multiple follow-up visits. Have a conversation with the people you are filming early on in the reporting process so that they fully understand what might be expected of them during their participation.

Similarly, you should have a conversation about the depth to which you want your story to go. This is a delicate area, so you must tread lightly to avoid causing the subjects to think you are intrusive, which could ruin your chances for developing a more in-depth story. The message is: don’t scare away your subjects.

Sonya Hebert from the Dallas Morning News produced a profoundly somber, emotional story about a couple that loses an infant son to a rare birth defect. Hebert gained the trust of the family, who allowed her to remain with them, video camera rolling, while their son actually dies. Photographing the moment of death indicates that a high level of trust has been established with family members.

There exists a delicate balance between scaring your subjects away by having them commit to giving their all from Day 1 and being utterly honest about what kind of commitment you need from them in order to satisfactorily report the story. Bob Sacha, a multimedia producer, photographer, filmmaker, and teacher whom we mentioned earlier, says he likes to be frank pretty early on in the reporting process. “I’ll tell my subjects, ‘I want to tell your story accurately, so I want to spend as much time here as I can.’ I want the experience to be a pleasant and positive one for the people. Basically, it’s all about building a good relationship with them. You don’t want to be a colossal pain in the neck. But you don’t want to waste time and go nowhere either.”

Sacha says he frequently has to be persistent to get his subjects to be fully participatory. “When you show up more than once, the people may be impressed by your level of commitment to telling their story well. By the third, fourth or fifth time you visit them, they will be comfortable with and even flattered by your dedication to their story. Such proof of your dedication will often open the final door to the degree of intimacy you’ve been waiting for.”

Dai Sugano, a multimedia journalist at the San Jose Mercury News, agrees. “It’s all about maintaining a relationship,” he says. “When a person sees that you are consistent and committed to the story, they tend be more accepting of your presence. You know you are in a good position when the subject stops asking, ‘Why are you taking that picture?’ If you have established good rapport, the people may even begin to contact you about upcoming events in their lives. This obviously precludes your having to constantly ask them probing questions.

“There is no magical way for you to know what people are thinking, especially when you first meet them,” says Sugano. “It’s really not a bad idea to put in the extra time to fully explain what it takes for you to tell the story well. Don’t be afraid to inform them that things might not always go as smoothly as you both hope at the outset.

▼ T.K. Laux feels for Thomas’s heartbeat during one of the many recurring episodes of silence followed by gasps. “We love you, big boy. Please go home,” Laux kept saying. “Thank you, Thomas. Please go.” “Just let him do it his way,” Deidrea said with a sigh. Again, Thomas gasped after ten minutes of silence. “There’s nothing we can do.”

▲ “Choosing Thomas” Deidrea Laux sits on her bathroom foor holding Thomas before making a plaster mold of his hands and bathing and dressing him for the last time. “I got to feel what it’s like to be a mom. It was good, Thomas. Thank you. I needed you,” Deidrea said to her baby. The video-journalist was able to capture this very intimate moment in a couple’s life. ![]()

(Photos by Sonya Hebert, Dallas Morning News)

“When you are making a documentary, you can’t really predict what’s going to happen next. Things have a way of just happening. And you simply don’t have time to ask for permission when they happen—one more reason why it is so important to explain the ground rules early on. If not, later on you could find yourself in a situation where the person you’re filming thinks you have crossed a line and are being intrusive or rude. Of course, you can always explain afterward why you needed to photograph the subject in a sensitive moment, but if the person knows ahead of time that you might eventually tread on some delicate territory or other, they will be more likely to allow for those awkward moments without resistance.”

Sugano shot and produced a story called “Torn Apart,” which chronicles the story of a family of immigrant parents and American-born children who are faced with the parents’ deportation. He followed the family for close to a year. “I photographed many stressful situations, including an occasion where an eldest daughter was emotionally overwhelmed. I took the trouble to later explain to her why I had photographed her crying. That way, she better understood why the picture was so important as it showed the pain she felt over being forcibly separated from her father,” Sugano says. ![]()

▲ Torn Apart. Immigrant parents and American-born children face the possibility of the parents’ deportation. This story took the videographer a year to complete. He explained the photographic process to the family before he started so they would accept him over the course of the saga.

(Dai Sugano, San Jose Mercury News)

He adds, “It is important that the people understand what they are agreeing to when they give you permission to follow their journey. Otherwise, major misunderstandings can occur later, which can completely derail the story. That said, you may not want to go into extravagant detail or push for definitive ground rules in the beginning as when it works well, the process of filming peoples’ lives quite naturally evolves as the gradual building of a trusting relationship.”

A Take-Away Moment?

Once we have good characters and a sufficient narrative to keep our audience interested, a story should also have a take-away message. Perhaps there is a lesson or moral to the story, or maybe it just teaches us something we didn’t know enough about. Maybe it serves to make us laugh or cry, but every story must have a purpose to it that will linger after the viewer absorbs the last picture.

More Than Strong Visual Impact?

The story is the most important part of a video or multimedia project. Without it, you have nothing. That said, we work in a visual medium, and your project should also have strong visual impact. Strong visuals on their own can’t carry a multimedia story, but they most certainly will raise the level of its quality.

▲ Take Care. The producer was first attracted by Virginia Gan-dee’s brilliant red hair and dozen tattoos—but then went deeper. Inside Gandee’s family’s Staten Island trailer, she cares for her grandfather. ![]()

(Photography and video by Gillian Laub, MediaStorm)

Eric Maierson, a producer for MediaStorm, says that sometimes the initial attraction to a story might be purely visual. “There are people who create interesting visuals,” says Maierson, “and that’s their thing and there’s nothing wrong with that. But if you’re a journalist, you need more than just interesting visuals. You must have a story.”

A story that Maierson helped produce called “Take Care” was discovered by photographer Gillian Laub, who had noticed the story’s main subject, Virginia Gandee, a 22-year-old woman covered in tattoos, waiting for the subway. The initial attraction to her came out of a purely visual interest. But the story that Laub discovered about the tattooed woman was that Gandee was not only a single mother, but she was also the caretaker for her dying grandfather.

“That is what’s compelling about the story,” says Maierson. “In addition to having great visual potential, a good story must have a narrative that an audience can connect with. Furthermore there is great contradiction in this piece. Gandee is a hard-rocking woman with tattoos, yet she cares for her grandpa,” says Maierson. “That contrast shocks the hell out of your audience.”

A story that has visual potential refers to the idea that at least part of the story is going to unfold in front of you and you will have enough opportunities to show rather than tell that story to your audience. With this approach, one is thinking like a still photographer. Other times, as in the story “Take Care,” you might feel that your subject has a look about him or her that catches your fancy. That initial curiosity might lead you to find a terrific story. As storytellers, we must be perpetually on the lookout for opportunities to record real moments that we can bear witness to with our cameras and microphones.

Every story you do will fall somewhere along a continuum of either great visual potential or strong narrative potential, so logically part of your decision-making process has to be to make a choice about where you want to and are actually able to take the story. Many stories that seem to have little visual or narrative potential on paper can end up becoming great storytelling opportunities. This is due in large part to the thought process of the photographer or storyteller. Think about all of the options you have before writing a story off. There is no one way to tell a story.

Can You Capture Revealing Moments?

While a graduate student at Ohio University, Yanina Manolova produced a series of video stories on women living in the Appalachian region of Ohio—women who struggle with recovery from substance abuse and domestic abuse within their homes. She tracks the women every step of the way, following them through treatment, visits to prison and even during violent encounters in their own homes.

Simply interviewing the women about what had happened in the past would certainly have been powerful, but Manolova realized that whenever she could show rather than tell the women’s stories, the impact was tenfold. To tell their stories, she needed to actually document what was going on, including the drug use, the domestic violence and even sticky family situations.

▼ Neverland: A Short Film. Patricia, 27, smokes crack in Mansfield, Ohio. She graduated from the Rural Women’s Recovery Program in the spring of 2009 but relapsed in June of that year. Sexually abused at age 14 by a middle-aged man, her father’s best friend, she has been using alcohol and drugs (marijuana, crack, cocaine, oxycodone, and morphine) since. “I got pregnant with my daughter by a drug dealer, and I went for treatment for about nine months while I was pregnant. He is in prison and has never seen his child,” Patricia reveals. ![]()

(Photography by Yanina Manolova)

▼ Stephanie, 19, cries on her mother’s shoulder after graduating from the Rural Women’s Recovery Program. Due to drug charges that resulted in the loss of her two children, her probation officer ordered her to attend the substance abuse program. She started using drugs when she was with her ex-boyfriend, Carroll, the father of her daughter. “He beat me all the time, choked me, shouted at me, put a knife to my throat. I felt like shit. That’s why I used—so that I could hide my feelings. I started out with lower doses of Vicodin and Percocet, then I went to Oxycontin and heroin,” Stephanie says.

◀ Deanna, 33, cries in her temporary housing provided by the Salvation Army Shelter in Newark, Ohio. She has been physically abused by her husband. Deanna lost custody of her son and although she completed a substance abuse treatment program, she could not stop abusing alcohol. She is on the waiting list for another substance abuse treatment program.

▲ Clients of the Rural Women’s Recovery Program practice yoga.

▲ Jessica, 27, talks on the phone with her boyfriend during her relapse after having seven months of sobriety. She was abusing drugs and alcohol. She has survived several abusive relationships and has had five children from three different men and has lost custody of all of them. Jessica went for treatment at the Rural Women’s Recovery Program.

▲ Destiny, 4, poses in her stepfather’s car in Mansfield, Ohio. Her biological father was a drug dealer and was recently released from prison. She has never seen him. Her mother, Patricia, went through substance abuse treatment and graduated. She relapsed and went back on the streets again. Destiny lives with her grandparents in Mansfield, Ohio. “Why mommy keeps leaving me? She promised she will never leave me again,” Destiny asks.

▲ Deanna, 33, left, cries following a visit from her husband and son at the Rural Women’s Recovery Program, where she has been for two weeks. Her mother was an alcoholic, as are many of her family members. “I would get up and start drinking. Every single day. I will drink until I pass out,” Deanna says. Lisa, 44, right, is sad after her boyfriend’s visit at the Rural Women’s Recovery Program. Another alcohol abuser, she has been part of the program for two weeks. Lisa was sexually abused by her father at age six; her husband, a drug addict, sexually abused her as well, and she has three children by him, all of whom are drug addicts. “After I left their dad, the kids left me. Then I started drinking a lot more,” Lisa says. Hannah, 29, far left, talks to her mother, far right, during their family visit. Her alcohol problems began when she was fifteen. As a child, she was abused by her father.

▶ Hammoudi.

(Directed by Anwar Saab, produced by Tima Khalil) ![]()

Emotional Engagement?

You are well advised to use emotion in your story. Does your story explore feelings such as humor, grief, passion, or rage (to name a few)? Though not everyone will think the same things are funny or sad or inspiring, there are certain types of characters and stories to which the majority of people will react strongly.

In Anwar Saab and Tima Khalil’s story, “Hammoudi,” the audience listens to the very frank voice of 12-year-old Mohammad Hajj Mousa, who lost both legs to a military bomb while living in a Palestinian refugee camp. His blunt and honest discussion of attempted suicide and depression, mixed with his look at his own friendships and family, are topics of mutual interest to a wide audience.

We as an audience have great compassion for this child, and the storytellers, through Mousa, have tugged on a variety of powerful emotions to keep us hooked.

Broad Appeal or Niche Audience?

If your story has broad appeal to wide group of people of different ages, ethnic backgrounds, and economic levels, you’ll have the best chance of drawing in a large audience. The broader the appeal, the more people from varied backgrounds will have an interest in your work. You can’t expect absolutely everyone to be interested; but as part of deciding whether to pursue a topic, you have to examine whether you think a large enough audience will be attracted and engaged in your story.

Are you hoping for wide appeal, or are you producing for a smaller niche audience? If you intend your audience to be small, you may want to include more pertinent details that would appeal to such an audience. If your intention is to reach a more vast audience, you will have to think carefully about the details and depth you put into the project and decide whether the subject will be more universally appealing.

High Click Rate. MediaStorm founder Brian Storm observes, “You want to do one of two things to successfully market your work and get it seen by a large audience. You either want cats spinning on a fan—something short and funny that gets 50 million hits on You Tube—or you want to produce the greatest series ever done on Darfur, for example. What you don’t want to be is the noise in the middle.”

Part of MediaStorm’s success in terms of the numbers of people watching the stories there, Storm says, is due to the viral nature of the site’s following. “We want people to see these stories and be so moved that the first thing they do is repost them on Facebook or Twitter. One person can create a huge trail of viral activity. But it won’t happen for stories that don’t move your audience in some emotional way.”

Is Your Focus Narrow Enough?

Don’t attend events and merely cover them in a general fashion, stopping by here and there to shoot and interview a little bit of everything. Find a focus first. And stick to it!

In the Time.com story “Sudoku Master,” producer Jacob Templin covers the Sudoku championships. Rather than feature everything going on at the event—clearly a visually rich environment with plenty of interesting characters—Templin focuses on two players, both former champions and good friends, as they compete in the weekend tournament.

◀ Sudoku Master. Templin zeroed in just two players to tell the story of the Sudoku contest. ![]()

(Produced by Jacob Templin)

Their friendship, partnered with their competition, helps provide a focus on what could have been a banal story about this event. Again, zeroing in on the human interest within a general subject often makes the story sing.

Reasonable Deadline?

Many stories are produced in a few hours on strict deadlines; others take years or even decades to finish. How will your story fit into your schedule? Often, many editors do not understand the gobs of time it takes to both shoot and edit even a short piece. It takes even longer if you’re a little green and inexperienced. Shooting low-quality stories is easy and quick. Making great ones is usually not so simple or rapid. So be wise and plan ahead. Calculate in advance how long the entire process will take you.

Director and producer Taggart Siegel shot “The Real Dirt on Farmer John,” a full length documentary, over several decades. He began photographing a college classmate in the 1980s and continued until he felt the story was complete. He documented several major transformations in his lead character’s life. He followed him throughout the economic farm crisis of the 1980s. He documented his battles with local residents over his perceived lifestyle. And, finally, he brought to light the man’s success at building up a large community-supported agriculture farm that now supports many families in the Chicago area.

Sometimes, as happened to Taggart Siegel, you can’t put an end date on a story because you don’t know when or how it will finish. As it turns out, this type of long-term story is very compelling to an audience. They watch the lives of the characters unfold in much the same way and at the same cadence the documentary maker did while producing the story.

Of course, we do not all have the luxury of following a subject over many decades. Most of us live in a world of deadlines. All the more reason to figure out the amount of time you’ll need and discuss it with your editor so you both agree on a time frame. Many beginning video storytellers with too little experience in the medium make the mistake of underestimating the time they’ll need to finish a story. They end up rushing or racing into the office at the last minute panting and pleading for more time. Remember that turning out high-quality storytelling in these media takes lots of concentrated application and oodles of time.

▲ The Real Dirt on Farmer John. The documentary took several decades to create. ![]()

(Produced by Taggart Siegel)