CHAPTER 1

Telling Stories

▲ Train Jumping: A Deseperate Journey. The photographer rode the rails and the reporter provided a voice-over for this harrowing tale of immigrants trying to reach the “promised land.”![]()

(Photo by Gary Coronado/Palm Beach Post))

This symbol indicates when to go to the Videojournalism website for either links to more information or to a story cited in the text. Each reference will be listed according to chapter and page number. Links to stories will include their titles and, when available, images corresponding to those in the book. Bookmark the following URL, and you’re all set to go: http://www.kobreguide.com/content/videojournalism.

Or use your smart phone’s QR reader app to scan this code.

This chapter is about the many ways to tell a story and serves as an introduction to videojournalism as it relates to nonfiction storytelling. Videojournalism is not reality TV; it is not traditional front-page news articles. The secret to good videojournalism lies in finding and telling well-shaped, powerful stories in multimedia presentation. Most successful stories have a main character.

There are many ways to tell a story. You can do it chronologically—start at the beginning and end at the end. Or, you can disclose the most important piece of information first, and then reveal the rest of the story, bit by bit. You can tell the story through the eyes of your characters, or from the viewpoint of an outsider. As a videojournalist, you get to decide how you will tell your story—in a way that will compel your audience to stop, look, and listen.

NARRATIVE ARC

You Tell Stories All the Time

You already know how to tell stories. Don’t you do it all the time? When your car breaks down on the way to the hospital? Or your girlfriend or boyfriend leaves you? Or simply because your dog eats your homework? Then, quite naturally, you tell the tale to a friend.

How is your story different from the story in a novel or a movie? First and foremost, of course, your story is real. The events actually happened. They were not figments of your imagination. You did not invent the characters or the plot. Your story is nonfiction.

In this book, we will be dealing solely with true nonfiction stories—with events that actually happened in the past, are taking place right now, or might occur in the future. Herein we deal exclusively with actual events that happen to real people—not to actors, volunteers, or contestants. Again, this book deals only with reality.

▼ The Reach of War: A deady search for missing soldiers. The photographer gives a firsthand report of the patrol in Iraq that he went on and that ended in tragedy. Three soldiers were wounded. One died. The photographer’s images and narrative turn this incident into a gripping story. ![]()

(Michael Kamber, New York Times)

Reality TV Versus Real Stories

◀ Bachelor. When “reality” show bachelor Jason Mesnick selected as his final choice Molly Malaney, whom he had rejected six weeks earlier, some viewers figured the change of heart was one more example of TV producers meddling with the outcome of supposedly “real” situations.

TV shows like Big Brother or Survivors are loosely referred to as “reality shows.” But is reality TV real? Not quite. Reality TV shows such as The Apprentice, Fear Factor, and The Amazing Race are highly orchestrated and often partially fictionalized pieces of entertainment. They would not occur without a producer, multiple camera crews, willing participants, and bundles of money. These shows are contrived contests, not real stories. They would never have taken place without the creative energy of a writer, a producer, and a director. The outcome of such shows may be unknown at the beginning. But the setup is cleverly engineered to produce an almost fictional effect.

Real stories, on the other hand—those you see on television news programs such as 60 Minutes or on the Web at KobreGuide.com—reveal actual people living through the thrills and pitfalls of unadulterated events in their lives without the interference of a script doctor. ![]()

STORYTELLING OR NEWS REPORT

So how are stories you tell your friend different from front-page articles published in the newspaper or news segments broadcast on the six o’clock news with an anchor providing the lead-in?

Traditional News

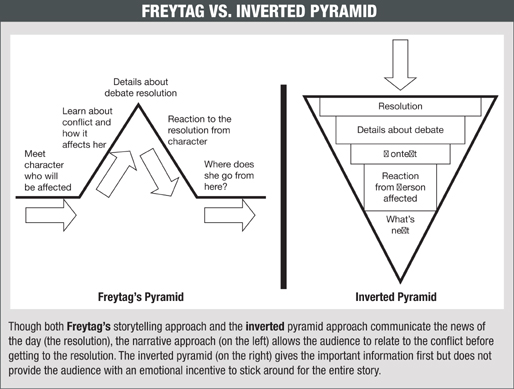

Traditional news stories required starting with the most important fact—a form of news reporting called the inverted pyramid.

News reports sound like this:

A fire burned 30 homes in San Bruno today.

The San Francisco Giants won the World Series yesterday.

Sometimes news reports are just headlines. Sometimes they have more supporting facts. These reports relate what happened today but don’t engage viewers with a character or plot.

Reports rarely introduce you to a subject, follow the subject from one state of emotion to another, see the challenge the person is facing, or reveal how the person resolves the problem. News articles and typical television reports are content to inform viewers. Storytelling, however, not only informs viewers but engages them emotionally.

Personal Story

Let’s go back to your original story about the calamity of getting to the hospital despite your malfunctioning car, tragically breaking up with your sweetheart, or losing your homework to your rambunctious dog.

When you tell your interesting story, why doesn’t your tale sound like a plain newspaper article or even a report on the evening news? It’s because you are telling your story in the form of a narrative, not simply reciting facts with the most important fact at the beginning.

And, of course, your particular story has a sympathetic character—you!

Your story evokes the problems you yourself faced with a car breakdown, a relationship breakup, or mangled homework. “Oh boy, my car broke down on the way to the hospital.” You might begin by exposing the problem. Then you might go on to explain what you did about overcoming the problem—how you had to call AAA and get a ride to the hospital in a tow truck; how many phone calls, gifts, cards, and letters it took to make up with your boyfriend or girlfriend; or how reprinting the brilliant 200-page term paper your dog ate almost made you miss the deadline for turning it in.

▼ Car Accident. Police officers hold up a white sheet as paramedics remove a victim from a Honda Civic that crashed on Robeson Street in Fayetteville, North Carolina. The victim died in the one car accident. A standard news story puts the most important facts first.

(Andrew Craft, Fayetteville Observer)

Your tale features a sensitive character (you!) facing an obstacle to overcome. Your adventure has a story arc—a beginning, a middle, and an end. Along that arc, you interject drama, humor, or insight as you reveal how you overcame the obstacle and what finally happened. In sharing your tale, you are—in the classic sense—a storyteller.

The Rise and Fall of Freytag’s Pyramid

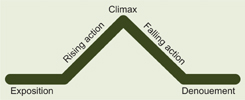

▲ Freytag’s Pyramid. Classic storytelling structure.

The narrative is a classic storytelling form. Just like a movie, a novel, or even a story you share with your friends, the narrative contains a clear beginning, middle, and end. On this path lie an exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and dénouement, or resolution—an arc known historically as Freytag’s Pyramid.

• Exposition provides an introduction to the character(s), the conflict, and the basic setting.

• Rising action reveals the complication in more detail.

• The climax is the moment of greatest tension in a story, a turning point (for better or worse) in addressing the conflict or complication.

• Falling action is what unravels after the climax. In some cases, this may involve continuing suspense, but the story is now heading toward its conclusion.

• Finally, the dénouement is where complications are resolved and the story comes to an end.

Freytag’s Pyramid, originally developed to analyze ancient Greek and Roman plays as well as those of Shakespeare, applies to documentary-style visual storytelling as well. You need to set up your story—characters, issues, location—in a way that allows events to unfold so that viewers learn more and more about the topic, the ways your characters are affected by it, how they develop a solution (or not), and finally, where they go from there. Just like the cowboy riding off in the sunset at the end of an old Western, at the end of your story, real characters go on with their lives.

▶ Consider a story about a vote on a proposed gasoline tax increase. Consider two approaches.

NARRATIVE VERSUS NEWS STORY

An Idea Is Not a Story

You may have tons of keen ideas for stories. But don’t confuse an idea with a story.

Steve Kelley and Maisie Crow of Maryland’s Howard County Times, for example, had the idea to document the effects of an incurable genetic disorder whose symptoms include insatiable hunger, low IQ, and behavioral problems. Although the disease is unusual, merely documenting Prader-Willi syndrome would only have yielded, perhaps, a well-done piece for medical students. But such a piece would not have told a story.

Instead of doing a mere report, Kelley and Crow presented the relationship between a teenage boy with the unusual disorder and his father, the boy’s caregiver. The effects of the disease are shown in the five-minute multimedia video

▲ Hungry: Living with Prader-Willi Syndrome. The story shows not only the disease but also reveals how that disease has affected the father-son relationship. Note how in this video the sound track including the ticking clock adds depth to the story. ![]()

(Steve Kelley and Maisie Crow, Howard County Times)

“Hungry: Living with Prader-Willi Syndrome.” The story reveals how father and son deal with the toll the syndrome takes on their relationship, and the strength they find to survive.

Your first goal, then, is to find the story in your bright idea: how to turn an idea—“Living with Prader-Willi Syndrome,” for example—into a story. The subject is the disease. The story is the relationship between the dad and the son who is afflicted with the disease. Once you have found the right story, your next goal will be shooting and recording it, writing a narration or script, and assembling the pieces during the editing process. It is crucial to tell that story in a way that engages viewers emotionally.

Good Storyteller or Bore?

Let’s face it. Some people are better narrators than others. Some start a story in the middle and have their audience nodding off within minutes. Others tell a story like it was a recitation of a list of facts. Yet others capture their audience from the opening words of “You won’t believe this but when I …” to the final words “and then I got out safely.”

What makes one storyteller electric and another tedious?

And, by the same token, what makes a short video documentary story that grabs viewers by their eyeballs and doesn’t let go until the final credits different from a dull documentary which inspires the viewer to click “next” after 10 seconds?

Good videojournalists do not just report facts. They employ classic storytelling techniques to present accounts about real people. They share their stories in the form of short documentaries, usually shown on the Internet, but also on television, sometimes even in theatres. Videojournalism applies the fictional storyteller’s techniques of character development and story arc to relate real-life tales of happiness, achievement, struggle, success, failure, and woe.

The secret lies in finding and telling powerful stories.

Kingsley’s Crossing: A Compelling Narrative

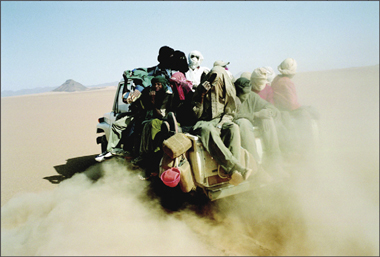

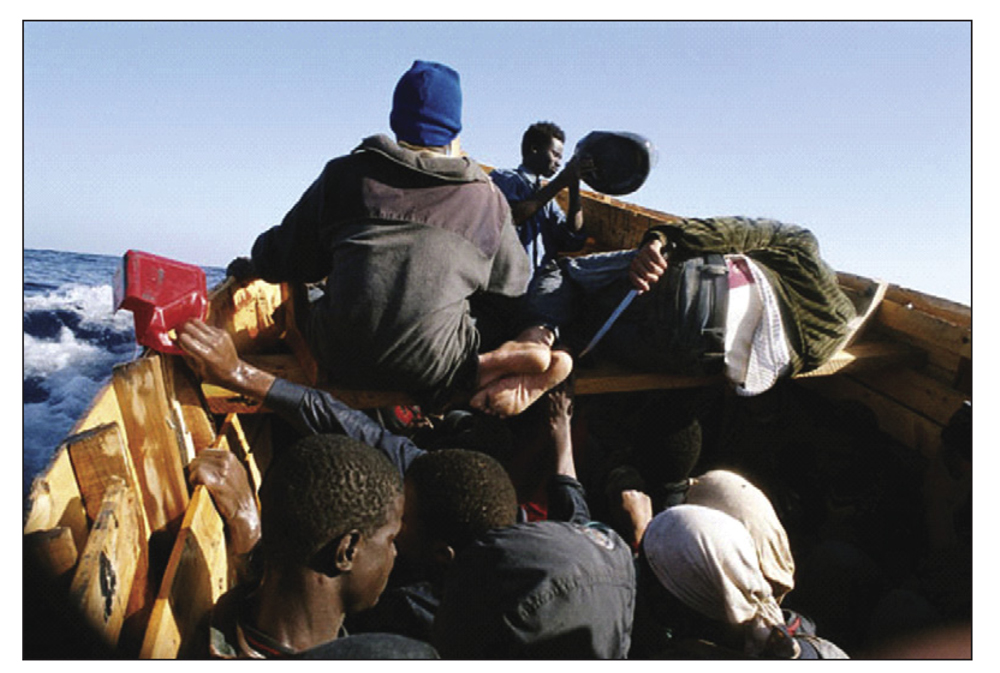

Photographer Olivier Jobard of Sipa Press and producers Brian Storm and Eric Maierson of MediaStorm tell the story of Kingsley, a poor young Cameroonian man who is driven to emigrate to Europe to find a better life. Why? Because Kingsley faces poverty and stagnation at home. He is poor and going nowhere. He feels he must emigrate, to go elsewhere, to seek an escape. The blazing complication confronting Kingsley is the fact that he must emigrate illegally. As detailed in the multimedia piece “Kingsley’s Crossing,” the young man faces one perilous hurdle after another.

Kingsley was a 23-year-old lifeguard from the Cameroon in West Africa. As a lifeguard, he earned just enough to pay for food and the rented two-room house he shared with his parents and seven siblings. In Europe—the new El Dorado—Kingsley knew that African immigrants could vastly increase their incomes while also providing for their families back home.

Photojournalist Olivier Jobard was vividly aware of the wave of African immigrants desperately seeking better lives and economic opportunities in Europe. To illustrate the conflicts facing these young people, Jobard decided to document one person making the treacherous, illegal journey from Africa to Europe. After paying the smugglers, Jobard and a friend who is a videojournalist made the crossing with Kingsley.

The multimedia presentation of “Kingsley’s Crossing” on MediaStorm.org combines Olivier Jobard’s still images with a videotaped interview of Kingsley. The face-to-face on-camera interview introduces Kingsley to viewers. With this effective device, people get to hear the young man’s story in his own voice. They are therefore engaged emotionally as he describes his Deseperate journey in his own words.

▲ Kingsley’s Crossing. Kingsley, a 23-year-old Cameroonian, ponders migrating to Europe, where he hopes to have better job prospects and an improved quality of life.

Kingsley: “I was really scared not to fall off from the car because I was sitting just at the side at the edge of the car. And behind me there was guys fighting. ‘Get off my leg, my leg, please, my leg.’ The more we driving, the more we suffer from heat, sun, and dust.”

Kingsley: “The captain successfully crossed the waves. Water was getting in everywhere. Rapidly. People become more and more frightened. Guys were shouting, ‘Hey captain, turn back, turn back, turn back!’”

[At this point, a Spanish Coast Guard boat comes near.]

“They [the Spanish Coast Guard] told us nobody should make any move. Our boat might capsize, so they were calling us one after each. We were very, very happy. Now my life is safe.”

Kingsley: “I contacted my only friend. We have grown up together. He’s married to a French woman living in France. So I phone him and let him know that I’ve arrived. At the train station I was there waiting for my friend. He arrived behind me, and when he touched me it was a joy. Shouting, rejoicing. It was something marvelous. Later he carried me with his car to his house. Met his wife. We spent all our time talking. That day was really an exciting one. Crossing the ocean, the desert, that was the only way for me to make it out. And I did it.”

(Photography, Olivier Jobard/Sipa Press; Producers, Brian Storm and Eric Maierson, MediaStorm) ![]()

SHAPING A STORY

This is your challenge: how to shape your story and design the story’s structure. Sometimes— but rarely—you’ll know how before you even record the story. Most times, however, the story structure develops while you’re working in the field. Sometimes it doesn’t even develop until editing begins.

Three-Act Play

Many storytellers think of structure as a three-act play.

Act 1. Introduce your characters. Let us meet them; give us a reason to care about them and introduce the key layers of conflict.

Act 2. Reveal the complication. This is usually the longest part of the story. The act reveals how the layered complications intensify—there’s no easy fix for the conflict from Act 1—until the final showdown: the crisis.

Act 3. Resolve the conflict/crisis, and finish the story in a satisfying way. This act reveals the choices made in the crisis and how these choices are resolved.

The three-act play design is as old as ancient Greece and as modern as the most recent Hollywood release. Watch movies, TV shows, and even some commercials closely for structure and you will see the three-act construct used over and over again.

In “Hungry: Living with Prader-Willi Syndrome,” mentioned earlier, the first act introduces you to the father and son. The second act explains the disease. And the third act shows how the disease brings the father and son closer. ![]()

In “Kingsley’s Crossing,” Kingsley emigrates illegally from Cameroon to escape the country’s grinding poverty. In Act 1, you meet Kingsley in Cameroon and come to know a little bit about him and why he is desperate to escape his present circumstances. In Act 2, you follow his harrowing adventures in trying to cross the desert sands and the Mediterranean Sea to reach economic freedom. Finally, in Act 3, you witness the outcome of his trials. ![]()

Complication and Resolution

In his book Writing for Story, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jon Franklin says that stories share a common structure but are a bit different than the three-act play. Franklin, who twice won the prestigious Pulitzer award for feature writing, says that stories revolve around a complication and its resolution. Good stories typically contain layers of complications.

Complications can be good or bad. Franklin defines a complication as any problem that a person encounters. Being threatened by a bully is a complication. Having a car stolen or being diagnosed with cancer is a complication.

In “Kingsley’s Crossing,” the central character recounts the complications he faces in his harrowing attempts to escape the grinding poverty of Cameroon and reach Europe illegally. You witness the roadblocks he must overcome as he tries to cross the dessert and the sea.

The story of “Kingsley’s Crossing” serves as an example of a three-act play but can also be analyzed using Franklin’s complication and resolution concept.

Complications are not all bad, Franklin says. Falling in love is a complication because you may not know whether the other person is in love, too. Winning the lottery means you get to figure out how to spend the money—but still you must pay the taxes.

Significant. Complications that lend themselves to journalism must tap into a problem basic enough and significant enough that most people can relate to it. When a mosquito bites you, you have a complication. But it neither reflects a basic human dilemma nor a significant universal problem. Discovering you have malaria and might die, on the other hand, is a fundamental complication that would be significant to most readers. Kingsley faced potentially deadly complications from every side as he battled his way towards what he thought would bring him a better life in Europe.

Resolution. The second part of a good story involves a resolution, which Franklin says in his book “is any change in the character or situation that resolves the complication.”

Whether you are cured of malaria or die from the disease, the complication is resolved. For stories with complications and resolutions, Franklin points out that most daily problems don’t have resolutions and therefore don’t lend themselves to creating terrific stories. After months of struggle, Kingsley’s story came to a resolution when he finally reached France and was able to stay.

External and internal conflict. Although Franklin is talking to writers, his central idea is applicable to many other story forms. Let’s dissect his central thesis and see how it applies to video. “To be of literary value,” he says, “a complication must not only be basic but also significant to the human condition.”

So complication—sometimes called “conflict” or “tension”—is an essential story element. Just introducing a character is not enough to tell a compelling story. Adding a complication—an obstacle to the character’s progress—enables us to relate to the person facing it.

Kingsley, the central character in the story “Kingsley’s Crossing,” had to overcome dangerous obstacles including highway robbers, breakdowns in the dessert and leaky boats, in his quest to reach Europe and a better life.

In many hard news stories, the tension is obvious: man against fire; woman fighting discrimination; child triumphing over a bully; police solving a mystery; neighbors battling over property lines; and so on. These all originate as external conflicts. Hence, they are easy to see and relate in a story.

Feature or in-depth stories can be much more subtle, as they may involve internal conflicts or reveal understated complications. Overcoming depression after a divorce, for example, involves an internal change in the person. The challenge to the person is just as big as if they had fought a fire or triumphed over a bully, but the changes take place internally. In any case, we now know that to be worthwhile to any reader or viewer, a story must contain tension.

The “Why” question. How do we identify and use this tension? When searching for tension in a story, it helps to start with one simple question: why?

What is motivating the character or characters? Motives frequently reveal tense inner conflicts and help us to answer the Why question. Merely showing someone creating a sculpture is not a story. It’s a demonstration of a process.

To get to the complication within the sculpting process, we want to ask an artist, “Why do you create these sculptures?” Using this tactic, we are likely to uncover some intriguing surprises. The sculptor might have a burning desire to form some image from his dreams or might want to experiment with how a particular shape looks when it is constructed from a unique material.

Peoples’ motives may include wanting to please someone else, or they may possess an inner compulsion they feel must be obeyed. Subtle motives such as these constitute complicating factors that help make up a more compelling story.

Protagonist wants change. Stories begin when protagonists want to change their lives, their environments, or something or someone else. Kingsley wanted to change his life. In fact, he had tried to reach Europe on an earlier attempt but failed. Protagonists may know they want to change consciously or unconsciously, but when an event throws their lives out of balance (sometimes called an inciting incident) protagonists decide to act. In any story you produce, look for the inciting incident that tips the balance.

So now we can see that a complication is established once the audience can identify a drive, or a pressing need, in a character. The protagonist wants to change.

CHARACTER-DRIVEN STORIES

Although every story does not have to have a main character, most successful stories do. Finding a compelling central character or group of characters can mean the difference between a lifeless story and an outstanding one. The young man with Prader-Willi syndrome is a sympathetic character that lets you feel his pain. Kingsley personalizes the problems of mass emigration.

The main character might simply be someone who has an intriguing tale to tell, or a person with a unique talent, an unusual achievement, or a quirky personality. Or your central character may be someone who can personalize a complex issue such as health care or environmental pollution.

Unique Talent

Here is a story based on a unique talent. In “Collin Rocks,” by Boyd Huppert and Jonathan Malat of KARE-TV in Minneapolis, our “hero” is a kid with a unique talent. As the story develops, we find out that he has a medical history and a personality that make him special. He’s a character worth knowing. Along the way, we meet a supporting cast, as well—his parents, sister, teachers—each of whom helps develop important elements of Collin’s story.

▲ Collin Rocks. Collin, the main character in this short video, has a personality that helps to bring the story to life. ![]()

(Boyd Huppert and Jonathan Malat, KARE, Minneapolis)

Personalize an Issue

The second possibility for a central character is someone who personally illustrates an important issue or problem. This character becomes Everyman or Everywoman and helps viewers relate to what otherwise might be a dry, tedious, fact-filled story. These characters’ individual situations can clearly illustrate such issues as government funding, health insurance, or the complexities of the legal system. By meeting so directly with someone struggling against an unyielding obstacle, viewers can both sympathize and even identify with the person. In this way, the viewer experiences a clearer, more emotional impact of how laws and regulations can really affect a single human being.

For an example of someone personifying a national problem, consider the story of Phan Plork and his wife Tal, Cambodian refugees who had found a home and a good living shrimping off of the Louisiana coast. Their lives changed radically after the BP oil rig exploded and polluted the water for hundreds of miles, shutting down commercial fishing. Now instead of shrimping, Phan’s boat and crew had to work soaking up floating crude oil with fabric booms. BP pays Phan a take-it-or-leave-it day rate for his services. That day rate is half what Plork made before the spill.

This Los Angeles Times video by Sachi Cunningham profiles the Plorks as they try to make the best of a disastrous situation, giving the viewer a personal look at the effect the spill has had on the fishing community. Tal prays for her husband’s safety while Phan and his crew, wearing protective suits and gloves, are seen hauling thick ropes of oil-soaked material from the water—a far cry from prespill days when they handled wiggling shrimp rather than toxic substances. It is obvious that with no experience, the shrimpers are ineffective at gathering oil.

In the video, Plork reminisces about his childhood days in Cambodia where he was starving under the Pol Pot regime. He tells us how much better his life has been in the United States until now. But this oil gathering is dangerous work for a shrimp boat that is likely to founder in the open ocean should a storm come up. “Looks like this is what we’re gonna be doin’ for a living from now on,” he tells his fellow fisherman.

▲ They Have Struck Oil But They Are Not Rich. Phan Plork is a commercial fisherman that lost a large part of his income because of the British Petroleum (BP) oil spill in the Golf of Mexico. The core of the video rests on Plork telling his own story.

▲ Phan Plork is the central character in a story that humanizes the impact of the British Petroleum oil spill off the Louisiana coast. ![]()

(Sachi Cunningham, Los Angeles Times)

▲ Denied. In “Denied,” the photographer and videographer tell the story of health care through the experiences of one woman who had to ask for help on the road side to pay her medical bills. ![]()

(Photo by Ed Kashi)

In “Denied,” directed and produced by Julie Winokur and Sheila Wessenberg, the central subject represents Everywoman and Everyman caught in the tangled web of the American health-care industry. Unable to afford escalating insurance premiums, the central character had to stop chemotherapy for breast cancer. She died the day before she would have been eligible for Medicare, the government-supported health care program.

STRONG, NUANCED PERSONALITY

Strong characters often become obvious—they have vivid personalities and the ability to speak clearly and are personally compelling. They should be like a friend everyone wants to hang with. They entertain us, enlighten us, and stay focused on the story they’re telling us. Wanting to hear more about someone when meeting him for the first time is a good sign. To spot possible strong characters, when you’re in the field on an assignment, looking for people to interview, watch for the person in the crowd who makes eye contact despite the fact that you are toting a camera.

Bethany Swain, a photojournalist at CNN who also produces the network’s photographer-driven “In Focus” series, says she asks others to help her find the right subject. “If I am going to interview one person in a group (such as a group of students), I will often ask them, “Who’s the most talkative?” or “Is there anyone you think I will enjoy talking to?” Swain’s method, she says, nets much better results than asking someone who the most important person is.

Strong characters are often nuanced characters: we get to see their strengths and vulnerabilities. We get to see them begin a journey to “right a wrong,” or “change a situation, or save a person’s life,” but strong characters also go through an arc, in which they will have to face grave doubt, fear, insecurity, and have to dig deep to find out not only what they truly believe, but also reconsider their goals and/or visions.

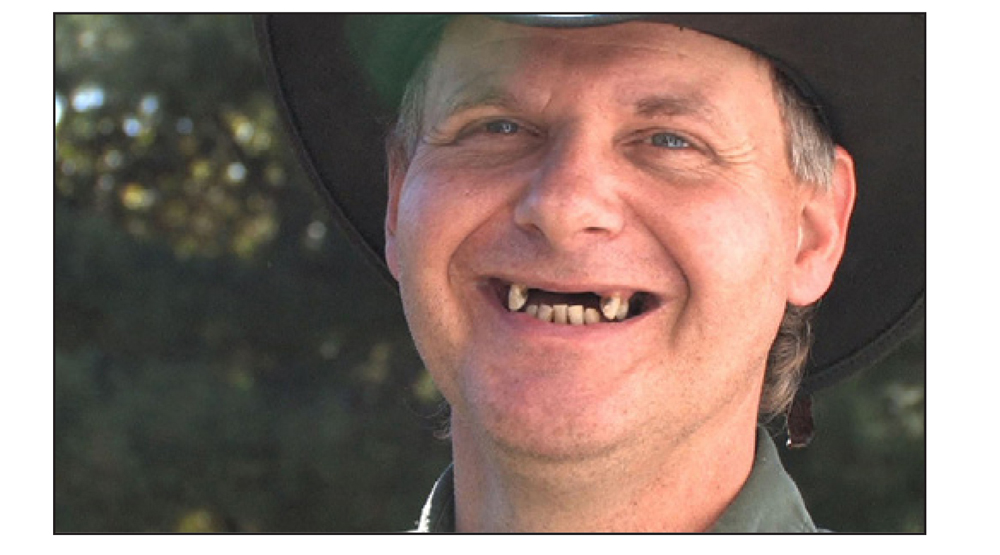

An Unforgettable Character

David Stephenson of the Lexington Herald-Leader found a great character in Ernie Brown, Jr., a snapping-turtle catcher in Kentucky. In Stephenson’s piece “Turtle Man,” Brown pops off one-liners in his thick Kentuckian accent and behaves in the most extraordinary ways. He dives into muddy water and pulls up a large snapping turtle with his bare hands, all the while giving an ear-splitting whoop of success. Brown’s is a story of the odd and the extreme, which is one reason this character appeals to such a wide audience.

▲ Ernie Brown, Jr., known as the Turtle Man, is trying to make a name for himself for his entertaining style of catching snapping turtles with his bare hands. ![]()

(Photo by David Stephenson/Lexington Herald Leader)

“Ernie is entertaining, and, in fact, he wants to be an entertainer. That is actually a big part of the story,” Stephenson says in an interview for this book. “In fact, Ernie tries too hard to be an entertainer, which ends up being funny. He’s odd and unusual, but simply put, he makes funny sounds—much beyond his dialect and accent— and he whoops and he hollers.”

Stephenson said that many journalists had done stories on the Turtle Man. So he and writer/narrator Amy Wilson decided to take the story a bit deeper. “We wanted to examine more about why Ernie Brown wants to become famous. Basically, he doesn’t have what it takes to make it big nationally or internationally. He’s really not sophisticated enough. But he does well at the kitschy, campy level, which will probably be fine for him. He’ll make money at it, and as he says, ‘I’m the poorest famous guy around.’” So Ernie’s tale, which on its base level is just funny and fun, was taken to a higher level of storytelling because the creators of the piece went one step further and looked into Ernie’s quest to become famous, albeit in his own weird and unique way. Amy Wilson and David Stephenson sought to engage viewers emotionally. And they succeeded.

Though Stephenson often works with a writer who will narrate parts of his stories, he prefers to let his subjects narrate their own stories. He says, “Whenever we can let our subjects have a voice … if they have the power to articulate, then all the better.”

Strong characters, though, don’t often make themselves as obvious as the Turtle Man. You must seek them out by opening your eyes and ears and sometimes holding dozens of mini pre-interviews while scouring your scene for just the substantial character whose presence will place a gentle five-minute hook into your audience’s attention span.

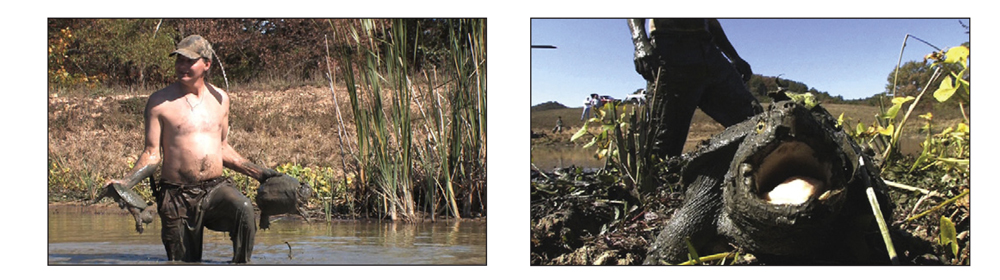

◀ The Turtle Man. Ernie Brown, Jr., pulled two snapping turtles from a Lincoln County farm pond near Stanford, Kentucky. Though catching snapping turtles is a unique occupation, Brown’s personality is what gives the piece its character.

An angry snapping turtle approached the camera after Ernie Brown, Jr., yanked it out of the mud from a Lincoln County farm pond.

(Photo by David Stephenson/Lexington Herald Leader)

Find Subjects to Tell All Sides

If your story centers on a public conflict, remember that one character is hardly ever enough. Each side of an issue needs to be represented by equally well-spoken and authentic voices.

Anticipating the 25th anniversary of what was supposed to have been a strategic bombing intended to clear a building of members of a controversial liberation group, editors at the Philadelphia Inquirer set out to produce a comprehensive multimedia package on the tragedy, which ultimately claimed 11 lives (including 5 children) and damaged or demolished 65 surrounding homes. The project includes entire archives of stories and photos related to the liberation group MOVE and its history. Four videos, a photo gallery, an interactive timeline, and extensive articles document and explore the impact of the tragedy through the voices of neighborhood residents, police and fire officers, politicians then and now, and the only surviving adult member of MOVE.

▼ The Unsettled Legacy of MOVE. In 1985, Philadelphia police descended on a city row house in an attempt to clear the building. The building was home to a strange back-to-nature liberation group known as MOVE. Unable to clear residents from the building using tear gas, the police department made the decision to drop a military-grade explosive bomb on the house, which resulted in 11 deaths (including 5 children) and the destruction of 65 homes in the resulting fires. Telling the story through multiple points of view based on a wide array of interviews, the producers looked at the effect of the bombing that took place in Philadelphia.

(Video by Sarah J. Glover, Laurence Kesterson, and Frank Wiese; video editing by Frank Wiese, Laurence Kesterson, and Hai Do) ![]()

◀ The Schools Are Tiny; The Game Is Huge. The story reveals the history of the rivalry between two small schools in Texas and then builds in anticipation as it follows the teams on the night of their highly anticipated annual showdown.

▶ The Texas towns of Gordon and Strawn are only eight miles apart and the high schools play 6-man football because they’re so small that they don’t have enough boys to field regular 11-man teams.

▶ Residents in both towns are crazy about football and once a year the neighboring teams play each other in a heated rivalry that began 86 years ago. The game is about as important as graduation, one player says. “All that matters is how you play on this night.” ![]()

(Produced by Jay Janner, narrated by Kevin Robbins, Austin American-Statesman)

Universal Themes

All humans share certain common experiences, such as birth, death, love, fear, joy, and, for many, a sense of competition. Universal themes might include: what it means to be a hero, looking at evil, defining success. If you are lucky enough to hit on a story that touches on universal themes, chances are your audience’s interest will be aroused.

Rivalry

The Texas towns of Gordon and Strawn are only eight miles apart and the high schools play 6-man football because the schools are so small that they don’t have enough boys to field regular 11-man teams.

The narrated audio slideshow, “The Schools Are Tiny; The Game Is Huge,” produced by Jay Janner of the Austin American-Statesman, is a well-crafted combination of stills, natural sound, music, and interviews. It reveals the history of the rivalry in the town and then builds suspense as it follows the teams on the night of their highly anticipated annual showdown.

Although not everyone has gone to a tiny high school in Texas, most people have experienced some from of rivalry or competition—for a job, for a scholarship, or on the playing field.

As part of AARP’s monthly series on triumphant mid-life transitions, “Your Life Calling,” NBC’s Jane Pauley profiles Robert Rudolph, 53, who left a mortgage-broker career and his 5,000-square-foot Atlanta home to return to his original passion—church music.

Through sit-down and walk-and-talk interviews, along with high-quality b-roll that incorporates images from throughout Rudolph’s adult career, Pauley elicits the saga of Rudolph’s professional rise, fall, and resurrection.

Rudolph had gotten a master’s degree in music. But, following in the footsteps of his businessman father, who valued getting a job that would pay enough to enable early retirement, Rudolph pursued a traditional corporate career. However, when the bottom fell out of the housing market, Rudolph saw an open door. While job hunting (in vain), he returned to his lifelong passion for church music, burning through all his savings and possessions in the process. Finally, a small church offered him a job, which led to another position as a choir director—and sure enough—Rudolph was soon pursuing a new life path.

◀ Rediscovering a Passion for Music. Robert Rudolph finally gets to live out his dream as the director of a choir.

▲ NBC’s Jane Pauley interviews Robert Rudolph, 53, who always wanted to be involved in church music. ![]()

Identifying universal themes like competition, a dream, birth, death, love, fear, or joy in a particular situation is a way to connect your story to your viewers’ lives. (See Chapter 3, “Successful Story Topics.”)

A SLICE-OF-LIFE STORY

A slice-of-life story dissects the ordinary life of someone or some place with which the viewer is probably unfamiliar.

Point of View

The slice-of-life story has a point of view. A story of this kind might document how a single mom manages a household while juggling jobs and raising kids. The videographer doesn’t just document every moment of the woman’s life but selectively captures the scenes that reveal the challenges of single motherhood. A slice-of-life story might document a chef driving his pop-up food van and delivering gourmet meals to hundreds of eager customers. The story could concentrate on the pressures the cook faces every day to meet his demanding clients. A slice-of-life story following an emergency room (ER) nurse on a Saturday night could highlight the contrast between hours of total boredom and the seconds of flat-out stress during an evening in the ER. Even a casual observation of the life of an immigrant gardener might show how he handles the demands and whims of his well-heeled clients. A slice of life of a place might tease out what makes a small French town so French. The video would highlight the aspects that give the town its special character.

Slice of Life Versus a Narrative

▲ Johnnie Footman: New York City’s 90-Year-Old Cabbie. At 90, Johnnie Footman is probably the oldest cabbie driver in New York City. Footman’s quirky personality, captured as he spouts his opinions on his customers, women and his past, provide the story’s point of view.

(Photography and video Jan Johannessen and Charlotte Oestervang; audio Scott Anger and Charlotte Oestervang; editing Scott Anger and Megan Lange; produced by Scott Anger and Megan Lange/MediaStorm) ![]()

In a narrative story, as discussed earlier, the protagonist faces a complication in life and either the person or the situation changes. In a slice-of-life documentary, nothing changes. A conflict is not resolved. No resolution occurs. Instead, observes Denise Bostrom, screenwriting instructor at City College of San Francisco, the viewer gets to see the inner working of another person’s life or another place. These people or places serve to make a point the videojournalist wants to emphasize. These kinds of stories can reveal the stress of a single mom, the pressures of a chief, or the “Frenchness” of a French town.

In a story called “Jonnie Footman, New York City’s 90-Year-Old Cabbie,” videojournalists produced for MediaStorm a slice-of-life personality profile of this lively, opinionated cab driver who still navigates the streets of the big city. This memorable character’s spunkiness provides a point of view in the video.

In Travis Fox’s short video documentary “Portrait of Coney Island,” the videojournalist presents a slice-of-life portrayal of this soon-to-be demolished amusement park. Without the aid of any voiceover to explain what the viewer is seeing, he lays out some special aspects of this nostalgic, pre-Disney entertainment spot. Fox’s point of view comes across clearly in his subject choice. He has chosen to highlight some of the more bizarre aspects of the boardwalk.

PORTRAIT OF CONEY ISLAND

◀ Sideshow tent. With the purchase of most of Coney Island’s six-block area by a commercial developer, Travis Fox’s short documentary captures the last of its pre-Disney past. ![]()

(Travis Fox, The Washington Post)

◀ Cyclone Roller Coaster.

◀ Barker with a screwdriver up his nose.

◀ “Shoot the Freak” paintball.

DAY-IN-THE-LIFE

A day-in-the-life story records the activities of someone through a period of time—such as the length of a day. The videojournalist shoots everything in hopes of capturing revealing details. But most people’s daily lives are not actual stories. See if you can remember any of the individuals or the stories featured in the many beautiful picture books with the theme “A Day in the Life.” You can’t? Why? Because the Day in the Life books consist of beautiful images, but the individual pictures don’t add up to tell a coherent story.

Central Theme, Point of View Lacking

There are other differences, too, between a day-in-the-life and a true story approach. A day-in-the-life video has no central theme or point of view. Someone doesn’t necessarily face and/or resolve the conflict and resolution of an external or internal problem even if you follow them from morning to night (as discussed shortly). A day-in-the-life video is merely documentation of what happens over a period of time.

When possible, look for a better story plot than a day in the life of your subject. Day-in-the-life projects make nice coffee table books, where there is little competition for attention, but they do not work as stories told for the Internet.

From Day-in-Life Idea to Themed Story

Seasoned photojournalist Eileen Blass, a staff photographer at USA Today, was attending a Western Kentucky University Mountain Workshop on multimedia storytelling when she selected as a story idea a Kentucky family who runs an organic farm. Bob Sacha, a multimedia journalist and Eileen’s coach at the workshop, asked her to explain in two minutes or less what the story (not the idea!) was going to be about. She replied that her plan was to make a story about how this farmer had to work a second job as a conservation officer in order to maintain the family farm—basically a day in the life of a man struggling to maintain his farm. “But I didn’t have a focus beyond that,” Blass admits.

Her plan, Blass told her workshop mentor, was to hang out for a couple of days and hope that the story would sort itself out. “Without an interview, I really didn’t know what the story would be. So for the first day or so, I shot everything in sight—a few hours of tape,” Blass recalls.

“I’m actually personally interested in organic farming and healthy eating,” she says, “but even I had no real interest in the story so far. For me— and for a general audience—I still wondered why we were going to connect to the story. I knew that a broad audience wasn’t going to connect because of healthy eating or organic farming. I needed some other, more universal and emotional draw. Frankly, at that point my story sounded pretty boring,” she said in an interview after the workshop.

Blass says she was pretty lost on the first day, so she was shooting everything in sight. She did conduct interviews, trying to make some kind of story pan out of her original idea. But it still didn’t have the necessary emotional attraction that Bob Sacha wanted.

Finding a Theme

Says Blass, “All along I’ve been told that at the end of an interview I should always ask, ‘Is there something else I should know?’ I did just that with the farmer, and that was the moment when he really told me what was on his mind. He explained that a good friend, an older farmer, had just passed away. As he told me about his friend, he became very emotional and teary-eyed. I certainly didn’t expect that,” she recalls in an interview for this chapter. “It really took me aback. He cried about his friend who taught him how to make sweet sorghum, and how he planned to preserve that tradition. So at that moment, I knew I had the story.”

Her idea to follow the farmer’s efforts to maintain the farm while working another job became instead a story about relationships, tradition, loss, and love. These are the types of themes that a broad audience can and will relate to on an emotional level.

Blass’s final story, just over two minutes in length, centered on these universal themes—still showing, of course, that the subject is an organic farmer. But as the farmer moved through his day, Blass’s story focused on emotional issues, to which an audience can connect.

Concise Description

A handy measure of whether you have a decent story is to try to describe your story in two or three sentences to another person. With a little practice, you should be able to concisely introduce the characters, set up their conflicts, and evoke their challenges.

Eileen Blass might describe her story this way: “This is a story about a young organic farmer dealing with the loss of a dear friend and fellow farmer. To help deal with this loss, he preserves the traditions taught to him by his late friend, and honors him by practicing what he was taught.” If you can reduce your tale to a few concise lines and make it worthwhile for someone to listen to, chances are you’ve got yourself a terrific story.

▼ Tethered to Tradition. Brad Lowe feeds his chickens and turkeys on his family’s farm, Hillyard Field Organics in Murray, Kentucky.

The video became more than just a day in the life of this farmer because the videographer looked for universal themes. ![]()

(Produced by Eileen Blass)

AUDIENCE MUST CARE

So now you know much more about stories. All kinds of tales of human experience: adventure, escape, loss, rebirth, rivalry, revenge, sorrow— and then some—all of these can be foundations for stories. Of course, even with the most captivating theme, we still need a strong character or characters. We need the audience to care about the characters. It’s up to us to assemble the puzzle pieces of sound and pictures into a story that sings. One thing is certain: good stories are not just pretty pictures.