Scanning and skimming are probably two of the most useful skills in reading as long as you can overcome the fear that you will miss things if you don’t read everything with perfect comprehension at all times. Another vital skill that saves a huge amount of time is selective reading. If you understand how specific types of documents are structured you can get to the ‘meat’ without have to wade through masses of irrelevant detail.

Most of the techniques in this book concern improving speed whilst maintaining or improving comprehension and reading every word. The techniques in this chapter are the exception to this, since they involve trading comprehension for extreme speed. There are many instances when you don’t need perfect comprehension and recall of the material that you read. Maybe you are studying and need to ‘read around’ your subject to give you background information. Perhaps you need to read journals and magazines to keep you abreast of industry trends in your job. You may need to read preparatory documents before going into a meeting at very short notice. Despite the fact that these techniques do not involve reading every word, many people are amazed by how much information they are able to glean from a book or other reading source in a fraction of the time that even ‘normal’ speed reading takes.

These techniques can also be used to gain an overview of a book before deciding whether to read it from cover to cover. If using traditional reading, starting at page one and progressing through the whole text, you can spend weeks reading only to discover that the book didn’t tell you anything useful or relevant. Skimming and scanning form the cornerstone of effective studying that we will explore in depth below (Chapter 9). Finally, you can use these techniques to seek out relevant information on a webpage or large document without having to read the whole thing.

![]() ‘Newspapers, magazines, TV and computer screens are some of your windows on the world and, increasingly, the universe. It is possible, by understanding their nature, and some new approaches to them, to increase your efficiency in this area by a factor of ten.’

‘Newspapers, magazines, TV and computer screens are some of your windows on the world and, increasingly, the universe. It is possible, by understanding their nature, and some new approaches to them, to increase your efficiency in this area by a factor of ten.’

Tony Buzan, The Power of Verbal Intelligence

Scanning

Have you ever used a metal detector? You sweep it over the ground listening for it to beep as soon as it senses buried metal. Scanning reading works in an analogous way. You need to know what you are looking for before you begin and it helps to understand the layout of the book. Take a look at the contents page and index and have a quick flick through the pages as if you were in a bookshop deciding whether to buy it.

The first step is to identify specific questions that you need answered, key words or names that you are looking for.

We all have mental filters on our perception. What we notice or pay attention to is based on many factors, including upbringing, life experiences, beliefs and your current situation. If you are on a diet and hungry, food appears to tempt you in many places.

If you believe that the other queue in the supermarket always moves faster than the one you choose, you will notice every time this happens, reinforcing that belief and ignoring the times when you fly straight through.

If you buy a particular outfit you will suddenly notice that everyone is wearing similar colours or styles. Nothing has changed except that that colour or style has taken on increased importance to you.

In marketing, consumers are also more likely to retain information if a person has a strong interest in the stimuli. If someone is in need of a new car they are more likely to pay attention to an advertisement for a car, while someone who does not need a car may need to see the advertisement many times before they recognise the brand of vehicle.

This filtering is regulated by a part of the brain called the reticular activating system (RAS). The RAS consists of a loose network of neurons and neural fibres running through the brain stem. These neurons connect up with various other parts of the brain. The functions of the reticular activating system are many and varied but perhaps its most important function is its control of consciousness; the RAS is believed to control sleep, wakefulness, and the ability to consciously focus attention on something. In addition, the RAS acts as a filter, dampening down the effect of repeated stimuli. For example, the continuous background hum from a fan or air conditioning unit will quickly be ignored so that you don’t notice it. The brain’s RAS is constantly monitoring your environment to bring ‘important’ things to your attention. By identifying what is relevant, you can utilise this natural process to your advantage.

Once you have determined what you’re looking for, you can move your eyes across the pages very rapidly. It may help to use your finger to guide your eyes. We will cover guiding in detail in the next chapter. You are not aiming to make total sense of what you are seeing. If you cast your mind back to Chapter 2, this is recognition and assimilation without in-depth comprehension. As you have primed your subconscious to look for something specific this will ‘leap out’ at you when you come across it. You can mark the page to come back to later or read the appropriate paragraph in detail. Don’t allow yourself to fall into the trap of reading large sections or getting engrossed in the text unless it is really relevant. The aim is to survey the whole text in as short a time as possible.

I will build on this technique in a study context later in the text (Chapter 9).

Skimming

Skimming differs from scanning in the important respect that it is less pre-directed. If you watch someone skilled in skipping a stone across a lake you will see it briefly hit the water before bouncing off the surface and continuing to skip. Skimming reading is an analogous process. Your eyes fly over the text, never resting for long and dipping in here and there to take in the odd phrase or sentence. If you prefer, an alternative analogy is a swallow that spends the whole time on the wing. It catches insects in flight and skims over ponds and streams to take a drink, very rarely resting or perching.

Once again, you are not aiming for a high level of comprehension but you should get the gist of a book or report very rapidly. This is especially important either for relatively unimportant documents or if you are particularly time pressured. For example, if you are due in a meeting in ten minutes and you are expected to have read background notes, it would make sense to skim them rapidly rather than go in totally unprepared.

If I receive an email with a long attachment that I am supposed to review, I will often skim read it initially so that I can respond with my initial impression. If I am required to go into more detail at a later date I can speed read in more detail. However, I often find that skimming gave me enough information to serve the purpose without using up too much of my time.

Skimming is ideal for newspapers. Glance at headlines, photos, captions and the first paragraphs of articles. Look at diagrams and summaries if present. Skimming will quickly tell you which articles you want to read and keep. These can be marked with a coloured pen or torn out to read in ‘dead time’ whilst waiting or travelling. This lets you escape from the nagging annoyance of an unread paper. You can deal with it in 15 minutes and then can always go back and read at a more leisurely pace, for example at the weekend.

Skimming a book before reading it in detail is a really good investment of your time in that it will give you the skeleton of the text that can be fleshed out when you read it in detail. You can see much more clearly how the book fits together and put things in context.

Do you remember in the early days of the internet, before broadband, when everyone had to rely on a dial-up connection? Images were often encoded as ‘progressive JPEG files’. This started off by loading a very blocky image that became more detailed as extra data was downloaded. You eventually ended up with a clear photograph but could jump to another page before the picture had finished building up if it turned out to be irrelevant.

Getting an overview of a book can also save a huge amount of time.

A student at Oxford University had spent nearly a year reading a huge textbook before attending a public speed reading course. He had dutifully started reading on the first page and continued one page at a time, making notes as he went. He was nearly at his wits’ end, having got about three-quarters of the way through the book. He felt his head was ‘full’ and that there had to be a better way to study.

On attending the course he skimmed the book and discovered that the final chapter was a summary of the key points of the whole text. If he had read that first he could have saved himself the majority of the hours devoted to the book. Despite his initial disappointment he was easily able to pass his course armed with his new found skills.

Selective reading

Being selective with your reading can multiply the time saved from reading faster by a factor of four.

Being selective in what you read is a vital tool to reduce the time spent reading. If you understand how a document is put together you can zone in on the important information, get what you want and move on. Most documents have reams of text that go into far more detail than you need. Think of yourself as a detective like Sergeant Joe Friday, from the radio and television crime drama Dragnet, who would always say, ‘Just the facts, Ma’am’ when he was trying to get information to solve a crime.

Each type of publication or document follows a particular structure. If you know how they are put together you can use this to your advantage.

Court judgments

Court reporters know that judgments follow a standard format. The judge will normally review the case and the main factors in the majority of the document and then deliver their findings in the last paragraph. The reporters start reading from the last page, or even the last paragraph, because they are reading the judgment to report the verdict.

Magazines

Magazines will usually start with an editorial that will either be a personal view on a topical issue or set out what is in that issue depending on the ‘house style’. You will then come to the contents page. This will include a list of features, often with a one- or two-line description, highlight the main cover story and regulars such as a news section, letters, events listings, puzzles page, columns, etc. You can glean a lot from the contents page plus a quick skim through the magazine as a whole looking at large headings and glossy photographs, pausing occasionally to mark anything that catches your eye. Tear out pages of interest for later reading and discard the rest.

Scientific papers

Scientific papers always follow a layout so that a reader knows what to expect from each part of the paper, and they can quickly locate a specific type of information. The typical structure is as follows:

TITLE. The title will help you to decide if an article is interesting, relevant or worth reading. Included in a title are details of what was studied, the kinds of experiments performed, and perhaps a brief indication of the results obtained.

ABSTRACT. Abstracts provide you with a complete, but very succinct, summary of the paper. An abstract contains brief statements of the purpose, methods, results and conclusions of a study.

INTRODUCTION. An introduction usually describes the theoretical background, covers why the work is important, states a specific research question, and poses a hypothesis to be tested.

METHOD. The method section will help you determine exactly how the authors performed the experiment.

RESULTS. The results section contains the data collected during experimentation.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS. The discussion section will explain how the authors interpret their data, how they connect it to other work and will suggest areas of improvement for future research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. The acknowledgements tell you who, in addition to the authors, contributed to the work.

LITERATURE CITED. This section offers information on the range of other studies cited.

When reading scientific papers, you generally only need to read the title and abstract. If it looks interesting and you need more detail, you may read the discussion. It is only in very rare cases that you will read the whole paper.

Business reports

Well-written business reports follow a similar structure. Typically this includes:

TITLE. This gives a summary about the purpose of the report, the author and date.

CONTENTS. A list of the sections and appendices.

INTRODUCTION AND TERMS OF REFERENCE. The aims and scope of the report.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY. A one- or two-page summary containing evidence, recommendations and outcomes.

BACKGROUND. The historical situation and reasons for instigating the report or project.

IMPLICATIONS. Issues, implications, facts, figures, evidence (with sources) and possibly results of a tool like SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats).

SOLUTION. Options with implications, effects, results, financials, inputs and outputs.

RECOMMENDATIONS. Actions with details of input and outcomes, values, costs and return on investment analysis, if appropriate.

APPENDICES. Additional tables or supporting information.

BIBLIOGRAPHY. References to documents used.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. Credits to people who contributed to the report or whose work was referenced.

In much the same way as reading a scientific paper, a well-structured business report can be tackled by being very selective. Just read the title to see if it is relevant to continue, skim the contents and, if you think it is important, read the executive summary. This will usually be enough. In some cases it may be necessary to read the recommendations to see how this impacts on your work or department. In very rare cases, especially if you disagree with the recommendations, you may wish to read the implications to see what evidence led to the solution but this will almost never be the case.

I learnt this lesson when I worked as a computer programmer in a major bank. Each month a big folder would land on my desk as it was circulated around the department. This included that latest trends and economic forecasts from bank economists, general reports from senior management, sometimes HR policy changes and the internal company magazine. When I started as an eager, inexperienced graduate I would read everything. This lasted a couple of months before I realised that the majority of this was irrelevant. I learnt to discriminate, skim some of it and ignore the majority, then initial the distribution list and pass it on to the next person.

This is the worst possible advice for reading …

![]() ‘“Where should I begin, please, your Majesty?” he asked. “Begin at the beginning,” the King said, gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”’

‘“Where should I begin, please, your Majesty?” he asked. “Begin at the beginning,” the King said, gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”’

Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

STOP YOUR TIMER NOW (word count 2,599)

Comprehension questions

- Skimming and scanning are a trade-off between detailed comprehension and extreme speed. True or False? [1]

- Name one function of the reticular activating system? [1]

- Describe the difference between scanning and skimming. [1]

- What technique would you use to go through a newspaper quickly? [1]

- How much more time can you save by selective reading? [1]

- Which two sections of a scientific paper are usually all that needs to be read to get what you need from it? [2]

- Which three areas of a business report are usually all that needs to be read to get what you need from it? [3]

Check your answers in Appendix 1.

Number of points × 10 = % comprehension

Calculation

Timer reading

Minutes: |

|

Seconds: |

divide by 60 and add to whole minutes |

2,599/time = |

Speed (words per minute) |

Enter your comprehension and speed in the chart in the Introduction.

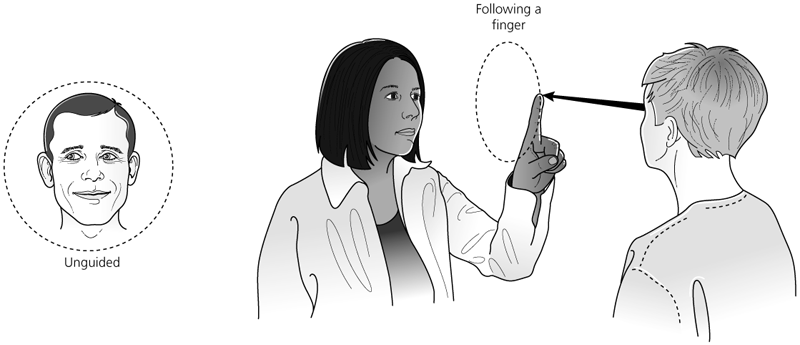

In preparation for the next chapter we have another little experiment for which you need to find a friend or colleague. It involves determining the difference between guided and unguided eye movement.

Sit or stand facing each other. As your partner watches your eyes, imagine a large, round dinner plate about 40–50 cm in front of your face, as if you were holding it up vertically. Now attempt to slowly move your eyes around the rim of the plate in a clockwise direction. Next, ask your partner to slowly move their finger, describing a similar-sized circle. Follow the tip of their finger with your eyes, as your partner once again observes how your eyes move. Do not move your head, only your eyes.

Exchange roles so that you both have an opportunity to watch each other’s eyes when unguided and when following a finger. Now see the next chapter.