Things to Remember When You’re on Location and the Flying Fecal Matter’s Hitting the Rotating Blades of the Air Circulating Device.

I have always thought of light as language. I ascribe to light the same qualities and characteristics one could generally apply to the spoken or written word. Light has color and tone, range, emotion, inflection, and timbre. It can sharpen or soften a picture. It can change the meaning of a photo, or what that photo will mean to someone. Like language, when used effectively, it has the power to move people, viscerally and emotionally, and inform them. The use of light in our pictures harks back to the original descriptive term we use to define this beloved endeavor of making pictures: photography, or photgraphos, from the Greek, meaning, to write with light. Writing with light! Cool!

It’s a big deal, right? As a photographer, it is very important to know how to do this. So why are so many of us illiterate?

Or more properly, selectively illiterate. I have seen photographers with an acutely beautiful sense of natural light, indeed a passion for it, start to vibrate like a tuning fork when a strobe is placed in their hands. Some photographers will wait for hours for the right time of day. Some will quite literally chase a swatch of photons reflecting off the side view mirror of a slow-moving bus down the block at dawn just to see if it will momentarily hit the wizened face of the elderly gentleman reading the paper at the window of the corner coffee shop. These very same shooters will look hesitantly, quizzically, even fearfully at a source of artificial light as if they are auditioning for a part in Quest for Fire, and had never seen such magic before.

I was blessed early in my career by having my self-esteem and photographic efforts subjected to assessment by some old-school wire service photo editors who, when they were on the street as photographers, started their days by placing yesterday’s cigar between their teeth, hitching up a pair of pants you could fit a zeppelin into, looping a 500-volt wet cell battery pack through their belts, and snugging it to their ample hips. Armed with a potato masher and a speed graphic (which most likely had the f-stop ring taped down at f/8), they would go about their day, indoors and out, making flash pictures. What we refer to now as fill flash, they called “synchro sun.” Like an umbrella on a rainy day or their car keys, they quite literally wouldn’t think of leaving the house without their strobe.

They brought that ethic to their judgment of film as editors. During the 1978 Yankees-KC baseball playoffs, I returned to the UPI temporary darkroom in Yankee Stadium with what I thought was a terrific ISO 1600 available-fluorescence photo of one of the losing Royals players slumped against the wall surrounded by discarded jerseys. Larry DeSantis, the news picture editor, never took his eye from his Agfa loupe while whipping through my film as he croaked in his best Brooklynese, “Nice picture kid. Never shoot a locker room without a strobe. I give this advice to you for free.”

That advice was pretty much an absolute and I have survived long enough in this nutty business to know there are no real absolutes. Sometimes the best frames are made from broken rules and bad exposures. But one thing that Larry was addressing, albeit through the prism of his no-frills, big city, down and dirty, get-it-on-the-wire point of view, was the use of light. What sticks with us, always, is light. It is the wand in the conductor’s hand. We watch it, follow it, respond to it, and yearn to ring every nuance of substance, meaning, and emotion out of it. It leads us, and we shoot and move to its rhythm.

I could wax eloquent about how, in a moment of photographic epiphany, I discovered and became conversant with the magic of strobe light. But I would be lying. Any degree of proficiency and acquaintance I have with the use of light of any kind has been a matter of hard work, repeated failures, basic curiosity, and a simple instinct for survival. I realized very early in my career that I was not possessed of the brilliance required to dictate to my clients that I would only shoot available light black-and-white film with a Leica. My destiny was that of a general assignment magazine photographer, by and large, and to that end, I rapidly converted to the school of available light being “any &*%%@^ light that’s available.”

Because light is just light, it is not magic, but a very real thing, and we need to be able to use it, adjust it, and bend it to our advantage. At my lighting workshops, I always tell students that light is like a basketball. It bounces off the floor, hits the wall, and comes back to you. It is pretty basic, in many ways.

Given the simple nature of light, I offer some equivalently simple tips for using it effectively in your photographs. Mind you, I offer these tips, Dos and Don’ts if you will, with the reminder that all rules are meant to be broken, and there is no unifying, earth-encompassing credo any photographer can employ in all situations he or she will encounter. All photo assignments are situational and require improvisational, spontaneous responses. At this point in my career, the only absolute I would offer to anyone is to not do this at all professionally, chuck the photo/art school curricula you’re taking that actually offers academic credit for courses called “Finding Your Zen Central,” and get an MBA. (However, if you’re reading this, it is probably too late.)

- Always start with one light.

Multiple lights all at once can create multiple problems, which can be difficult to sort out. Put up one light. See what it does. You may have to go no further. (The obvious corollary to this, of course, is to look at the nature of the existing light. You just might be able to leave the strobes in the trunk of your car.)

- Generally, warm is better than cool.

When lighting portraits, a small bit of warming gel is often very effective in obtaining a pleasing result. Face it, people look better slightly warm, as if they are sitting with a bunch of swells in the glow of the table lights at Le Cirque, rather than sort of cold, as if they had just spent the day ice fishing.

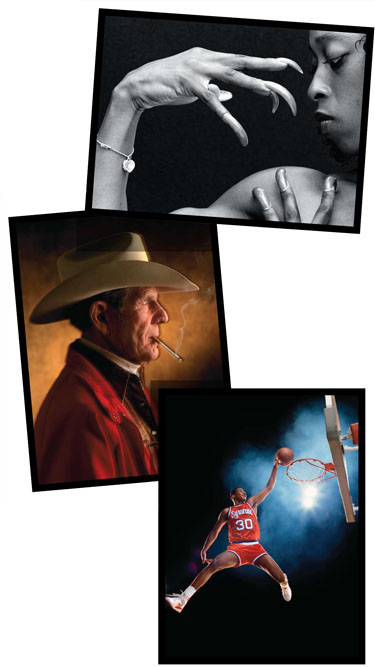

- Study Your Location - Where is there already light? Where’s it Coming From?

During location assessment, those crucial first few minutes you have when you show up on assignment and are looking around trying to determine how awful your day is about to get, look at where the light is coming from already. From the ceiling? Through the windows or the door? Am I going for a natural environmental look and therefore merely have to tweak what exists, or do I have to control the whole scene by overpowering existing light with my own lights? What does my editor or publication want? How much time do I have? Will my subject have the patience to wait while I set up for two hours or do I have to throw up a light and get this done? (Lots and lots of practical questions should race through your head immediately, because your initial assessment process will determine where you will place your camera. Given the strictures of location work, deadlines, and subject availability, this first shot may be the only shot you get, so this initial set of internal queries is extremely important.)

- Do Your Reshoot Now.

When wrapped up in the euphoria (or agony) of the shoot, do a mental check on yourself. If you are working long lens, try to imagine the scene with a wide lens from the other side of the room. Or think about a high or low angle. Always remember the last thing most editors like to see is a couple hundred frames shot from exactly the same position and attitude. Move around. Think outside of the lens and light you are currently using. Remember, shooting two or three hundred frames with the same lens, the same light, and the same angle is, uh, let’s see, how shall I say this? Repetitive and lacking imagination?

- Never shoot a locker room without a strobe. (Just kidding!)

- Remember, as an assignment photographer, that one “aw shit” wipes out three “attaboys.”

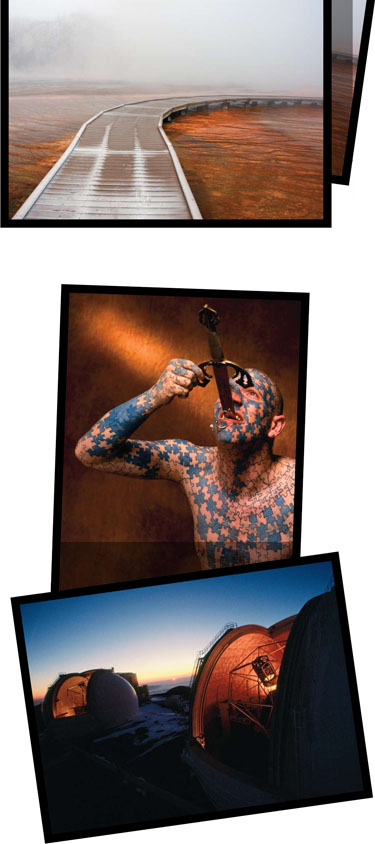

- Remember that the hardest thing about lighting is NOT lighting.

The issue here is control. It takes effort and expertise to speak with the light and bring different qualities of shadow, color, and tone to different areas of the photo. Flags, cutters, honeycomb grids, barn doors, gels, or the dining room tablecloth gaffer-taped to your light source will help you control and wrangle the explosion of photons that occurs when you trip a strobe. If you work with all these elements, and practice with them, you will soon see that in the context of the same photo, you can light Jimmy differently from Sally.

A good subset rule of this is: If you want something to look interesting, don’t light all of it.

- A white wall can be your friend or your enemy.

White walls are great if you are looking for bounce, fill, and open, airy results. They are deadly if you are trying to light someone in a dramatic or shadowy way. I carry in my grip bags some cut-up rolls of what I call black flocking paper (it goes by different names in the industry) that, when taped to walls, turns your average office into a black hole, allowing the light to be expressed in exactly the manner you intended.

- Experiment! You should have either a written or mental Rolodex of what you have tried and what looks good.

That is not to say that you should do the same thing all the time, quite the contrary. But, especially when you have to move fast, you must have the nuts and bolts and f-stops of your process down cold, so that your vision of the shot can dominate your thinking. All the fancy strobe heads, and packs, and C-stands, and softboxes you drag along with you should never interfere with your clarity of thought. All that stuff (and it is just stuff) is in service of how you want the photograph to feel, and what you are trying to say, picturewise.

- Don’t light everything the same way!

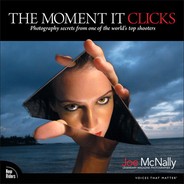

Boring! This would definitely be a close cousin to number nine. Clint Eastwood’s face requires a different lighting approach than, say, Pamela Anderson’s.

- If you’re getting assignments to shoot people like this, you don’t need my advice.

‘Nuff said! Good luck!