4 Implementation of privatization, 1992–1994

In Chapter 3 we observed that, unless it was part of a larger coordinated programme of economic and legislative reform, the Russian Mass Privatization Programme would be very limited in what it would be able to achieve. In Chapter 2 we noted that the political consensus to achieve comprehensive reform was lacking. The executive branch was split in its approach, and was, in any case, at loggerheads with the legislature. Most of the economic reform programme was enacted by presidential decree and, as such, arguably lacked a sense of legitimacy, although parliament itself accorded the president such powers and parliament approved most decrees. The passage of the Privatization Programme through parliament on 11 June 1992 was a key instance of consensus.

As we have also noted, there was a limit to what the ratified Privatization Programme had actually established. As discussed in Chapter 2 above, the legislation defined three things: first, the categorization of “objects to be privatized”; second, the method by which the privatization should take place and the rights afforded to the workers of companies (although it did not set out the terms for workers’ participation); third, who was to be in control of the process, and the length of time that their remit should run.

The Privatization Programme of 11 June 1992 did not establish the mechanics of the voucher programme, which were stipulated by presidential edicts separately, in August, October and November 1992.1 Those later edicts made clear how and to whom vouchers should be issued, and how voucher subscriptions would work, and the logistical problem of ensuring the issuance of vouchers before companies’ shares were auctioned.

In this chapter, we review the implementation of the 1992 Privatization Programme. We begin by looking at how different elements in the design of the programme influenced its outcome. We then look at the evidence of how the reforms were received on the ground, specifically addressing the context of the near-revolutionary changes which were taking place in Russia at the time. Finally, we reflect on what was achieved during voucher privatization: in terms of the “transfer of ownership”, in terms of how it changed the behaviour of the companies affected, and in terms of its contribution to wider economic reform in Russia.

Implementing the 1992 programme

Privatization of small enterprises

Much discussion has been given to the effects of the privatization of Russia’s large enterprises. Before addressing this question, it first may be worth reflecting on the privatization of small enterprises (those with less than 200 employees). Around three million people were employed at such enterprises.

In 1993, the GKI estimated that there were 76,884 enterprises of this size in Russia, though local estimates suggest that, once broken down to individual units, these may have numbered as many as 150,000.2 Around 55 per cent were shops, approximately 15 per cent were restaurants, and around 30 per cent were service enterprises. They were all to be privatized by August 1993. While this was not achieved, their privatization was swift. By the end of 1992, 47,000 small enterprises had been privatized; 80,000 by the end of 1993; and 96,000 by the end of 1994 (Blasi et al. 1997: xvi). GKI statistics tell a similar story, with 45 per cent of small businesses privatized by February 1993 (Åslund 1995: 362, note 74).

The overwhelming majority of small enterprises appear to have been purchased by their own workers’ collectives. Even in the 20 per cent of cases where sales were made by auction and without conditions, workers’ collectives won 60 per cent of the bids. One would have expected a higher success rate for insiders with tenders, which made up 50 per cent of sales and had conditions about preserving the line of business and the level of employment. The 30 per cent sold on lease with the right to buy were also likely to have been purchased by insiders.

In part, this was because substantial privileges were given to collectives. First, they were given a 30 per cent discount on the price, but perhaps more significantly they were allowed deferred payment over three years, which was of particular value in a period of hyperinflation. In a paper written at the time, one of the authors of this book reckoned that this meant “the workers’ collective [could] effectively purchase the enterprise for little over 25% of the cost to an outside investor”.3 Until October 1992, these purchases were for cash. After October 1992, vouchers were allowed for 45 per cent of the purchase, with local discretion to extend this amount.

Small-scale privatization was a local affair, organized through local municipal GKIs. Where local authorities wished to do so, enterprises were sold; if they did not, then, doubtless, the municipality held on to the asset. As the EBRD notes in its 1993 review, “If municipal authorities are determined not to implement privatization … under current political circumstance it may … be difficult for the Russian central authorities to enforce legislation”.4

In general, there seems to be little criticism of small-scale privatization. There were many problems experienced by small companies, including inconsistent application of laws, particularly on tax, as well as problems of corruption and extortion. However, these have either received little comment or have been treated as exogenous to the privatization process. Similar problems experienced by larger companies have been viewed as endogenous to the privatization process.5

It is to the privatization of those companies that we now turn our attention.

Privatization of medium and large enterprises

In Chapter 2, we described the terms set for the privatization of large enterprises, employing some 15–20 million people. In its initial conception, the Russian Privatization Programme envisaged the selling of companies, extending particular rights to the workforce and to the citizenry through the issuance of privatization accounts or vouchers.

The use of vouchers had one critical benefit. Hyperinflation meant there were no savings, particularly legitimate savings, which could have been used to purchase Russian companies. If a substantial block of the shares in privatized companies was to be paid for in cash, then this would effectively encourage those who had avoided the effects of hyperinflation and had the ability to access cash to purchase the enterprises. Few ordinary Russian citizens were in that position.

In the initial conception of the Privatization Programme of 1992, vouchers were to account for only 35 per cent of the shares of the enterprises to be sold. The rest were expected to be sold at auction. It was therefore most likely that the 65 per cent of shares that were not to be sold for vouchers would end up in the hands of those who had cash. Following hyperinflation, few people had such money, and many of those who did had acquired it in a questionable fashion.

Further, it was initially not clear, under law, whether vouchers were to be tradable instruments. The law of 1991 had talked of “privatization accounts”, and, according to Khasbulatov, it was envisaged that these would not be tradable.6 Had that proposal for privatization accounts been pursued, it would have resulted, initially, in a largely fragmented “ownership” base for enterprises. The question of when the shares in the company would become tradable or whether those who had bought shares with their vouchers were simply meant to hold on to them in the hope of some future dividend would have arisen later. In the meantime, auctions of shares not bought with vouchers would have established larger strategic investors who were able to buy larger stakes and hence would have the capacity to exert effective control over the enterprise. The reformers, on the other hand, were keen for the equity sold through vouchers to be consolidated as soon as possible. Consequently, the voucher programme, which was established by decree, abandoned illiquid privatization accounts and made vouchers tradable.

The challenge from associations and holding companies

The Privatization Programme required that enterprises be sold as individual units, rather than bundled as holding companies. However, it did little to prevent the creation of such companies during the privatization process. In particular, the associations, which we described in earlier chapters, could use privatization as a way of recreating holding company structures. The “associations”, which were born of the old Soviet system, often reflected the structure of the old Soviet branch ministries that coordinated production in various industries, and, in the chaos following the collapse of the Soviet Union they often provided valuable services to their members. In 1992, there was the very real prospect that these associations would use the privatization process to recreate the old ministry structure. A more detailed, contemporary account of the associations’ activities during the summer of 1992 is included as Appendix 2 below.

It shows that associations had the power, and many had the intention, to use the privatization legislation as a way of recreating holding companies that would reflect those of the old Soviet branch ministries. As noted above, following the passage of the 1992 legislation, the reformers were anxious to prevent this from happening since it would be inimical to open and competitive markets.

A comment by Andrei Shleifer, Chubais’s adviser during the privatization, in response to the proposal by Industry Minister Alexander Titkin that associations should take a central role in the privatization process suggests in its tone, as well as its content, policy differences between different government ministries:

Minister Titkin proposes to create syndicates that will put enterprises in the same lines of business and along the same technological production chain into the same organization … [he] believes that that such arrangements would make Russian enterprises look more like their western counterparts, stabilize the economy, encourage efficient restructuring, and promote growth and competition in world markets in the long term. On every count, minister Titkin is wrong.7

The complexities of decision making reinforced the “threat” that associations would undermine the purpose of the Privatization Programme. Below is a note from Bob Anderson, and others, consultants to the GKI in 1992. The note is dated 3 June, just before the passage of the Privatization Programme. It too reveals the gap in policy understanding between the reformers and officials even within their own ministry:

I had an informative but also disturbing meeting with the machine tool trade association, holding company, or whatever they are calling themselves… . The disturbing information is that the association seems to have negotiated its own privatization program both for itself and the entire industry with [a Deputy Chairman of the GKI]. Specifically, the association has obtained permission to convert itself into a holding company, which will own all of the other enterprises in the industry. This was approved by the GKI on May 14th (decree No 160).8 A Privatization Commission is now being created to supervise this transformation into a holding company.9

Anderson goes on to question whether “[the Deputy Chairman] is pursuing his own privatization strategy independent of Chubais and Vasiliev”. What is also notable is that the association felt happy to be explicit about their plans with Anderson, as were the 15 other associations he visited. Clearly, they felt the approach they were taking was legitimate, which is hardly surprising given that it accorded with that of Industry Minister Titkin. Four of the 15 associations that were interviewed were hostile to the privatization process.10 Most of the others had put together plans to create different forms of holding companies.

One of the key concerns of the reformers was to avoid the creation of such holding companies. As the Consortium notes in August 1992:

It is likely that many companies will choose their customers and suppliers as strategic investors. This will result in interlocking holding companies with significant monopolistic power. The privatization programme offers little protection against this outcome.

At this stage we have few foolproof solutions to the holding company problem. However the following suggestions may make them more difficult to create: (a) extend the voucher programme, offering more shares to small investors and funds; (b) lengthen the timing of the MPP to allow other strategic investors access to finance and company information; (c) encourage worker control under Option Two.11

They go on:

Like other strategic issues … the GKI alone cannot find the solution to the problem. It will require effective anti monopoly action to be taken. This in turn is only likely to work if there is a consensus for action amongst government members.

The extension in the use of vouchers made the realization of holding companies more difficult because it distributed shares broadly among the population. Rather than simply use the cash from one organization to buy up the next, associations would have to buy vouchers and compete at auctions with individuals and voucher funds. Further, enterprises privatizing under Option Two would already have sold 51 per cent of their shares to the workforce; hence association control would be more difficult to effect.

Thus, a central issue, following the passage of the 1992 Programme, was whether the privatization process would result in the creation of holding companies, with some manager/worker participation, or whether it would result in a more pluralistic structure, albeit one where enterprise managers and workers would gain greater control. Neither of these outcomes was what the reformers wanted. However, the latter outcome was deemed preferable to the former.

In fact, the “threat” from associations was greatly diluted by the expansion of the use of vouchers. Vouchers could be used not only for that portion of the proceeds of privatization that would otherwise have passed to the federal government, but also for that which was due to oblasts and local authorities. Given its potential effect on regional budgets, and the degree to which it made the formation of holding companies more difficult, it is remarkable that the decree to extend the use of vouchers was not challenged. It greatly reinforced the rights of enterprise managers and workers over those of the old ministry staff linked to the associations.

In combination with the popularity of Option Two, which created worker/manager control, this, to an extent, crowded out the influence of holding companies. However, it is unlikely that cross-shareholding structures of the type envisaged by associations could have been, or were, entirely avoided, particularly given the support they enjoyed within the Yeltsin government.

In December 1992, before privatization began, the Consortium concluded that “under the options given in the MPP, Russia [would] become one of the most worker/manager owned industrial structures in the world.” It also noted that, even with the extension of the vouchers, “some holding company structures [were] likely to be attempted during privatization” and that perhaps this was “not what the reformers initially intended”.12

However, there was a limited amount the reformers could do to prevent this structure from emerging. It would depend on whether those who were developing privatization plans within the enterprises were minded to encourage the creation of such structures.

As we noted in Chapter 2, privatization in Russia was a “bottom-up” process. The Russian government did not have the capability to implement anything else; had it tried to do so, the result would most likely have been the creation of holding companies such as those planned by the associations. So the question then became a political one: Could the managers and workers of the enterprise be persuaded to privatize along different, more pluralistic lines? Could they, as some of the reformers somewhat cynically put it, be “bribed”13 into supporting the process?

Response by enterprises

The 1992 Programme had laid out the options for privatization, as discussed in Chapter 3 above. But it had not laid out the terms on which subscriptions could be made for shares under Option Two; in other words, the price at which workers could buy the shares in their companies.

At this point, it may be worth looking in a little more depth at the terms of the privatization to address how they influenced incentives and choice of privatization options. Under Option One, 25 per cent of each company was to be granted to the workers at no cost, with a further 15 per cent to be available at 70 per cent of their book value on 1 January 1992. Under Option Two, workers could subscribe to 51 per cent at 1.7 times their book value on the same date.

The use of book values (i.e. historic accounting values) was necessary to strike the price at which workers could subscribe. However, given that Russia was suffering from hyperinflation, values based on historic costs could quickly become anomalously low. Nevertheless, calculations undertaken in the autumn of 1992 suggest that, from a purely economic point of view (and assuming no premium for voting shares), workers and managers would receive greater benefits by choosing Option One, which was indeed what the reformers wanted. As time went by, and inflation eroded the value of money, they may well have been more attracted to Option Two, since they could have bought a greater proportion of the shares, albeit at a higher price.

However, contemporary interviews of enterprise managers undertaken by western advisers in the summer of 1992 suggest that it was not these economic incentives that were foremost in the minds of enterprise managers. The preservation of control was the central issue in choosing which option an enterprise would adopt; their aim was to preserve the status quo. Enterprise managers tended to choose Option Two, or where this could not be afforded, versions of Option One that allowed them to preserve control. In those instances where the latter route was followed, interviewees noted that “schemes [were] being devised to have employees keep control of the majority of shares”.14

According to these interviews with enterprise managers, the primary challenge facing management was “the general macroeconomic state” and the operational problems it had created. These “directly threaten[ed] the survival of the enterprises in the short run” and “many managers [did] not see the link between these problems and privatization”.

There was “a high level of scepticism by managers about the ‘real’ intentions of the government’s [Privatization Programme]”, including the view that the government wanted to force companies to choose Option One so that it could remain in control with 60 per cent of the shares. And while enterprise management were aware of the general intent of the Privatization Programme, they were unclear on many issues, including rules on valuation and the use of vouchers. Many enterprises were seeking to implement privatization “using the newspaper reprints as their source of laws and decrees”. In these circumstances, and given the financial and other issues at stake, it is hardly surprising that different projects were hatched to take advantage of the legislation. These included creating trusts, buying workers’ shares collectively, and minimizing asset values. Interviews revealed that

some enterprises/associations … approached the central GKI regarding the holding company idea, and were encouraged by the central GKI to pursue approaches which [lay] outside the bounds of the spirit of the current MPP approach with regard to holding companies. There appears to be conflicting central GKI policy on the issue.15

It should be noted that these interviews took place within six weeks of the deadline for enterprises to submit privatization plans.

Nevertheless, enterprise managers were relatively supportive of the programme. Interviews reported that less than 25 per cent of them were hostile, while over 40 per cent were supportive. The rest were described as “obedient”, meaning they would comply, but without any particular enthusiasm to do so. By September, almost all enterprises had plans to corporatize, and nearly 90 per cent had formed commissions to do so.

In some ways, this is unremarkable. After all, it was the law. However, if enterprises had decided not to implement the law, many would have found it fairly easy to qualify as an “exception”, claiming, for example, that they were monopoly producers. The only sanction would have been the withdrawal of the rights that the workers and managers would have enjoyed under the legislation. This proved enough to tip the balance in favour of implementation. However, that implementation was never likely to be carried out with the precision that could be expected in less turbulent circumstances. The Consortium reported in October 1992 that “Most enterprises are proposing to follow the law to some degree … but … lots of financial schemes [are being] hatched which may not be in the spirit of the reforms.”16 It went on to quote from interviews with two Moscow-based enterprises. One, a speciality steel company, reported that 60 per cent of its shares were to be put in trust for the workforce for later resale. The other, a textile company, reported that it “would be its own strategic investor”. Neither of these proposals sound as if they were within the spirit of the Privatization Programme, though, at least in the former case, the company reported that it had discussed its plans with the GKI.

Voucher design and its effects

So far we have explored some of the issues facing enterprises. There were also problems associated with the use of vouchers by purchasers. These, in turn, affected the outcome of the privatization.

We have already noted that the use of vouchers as a mechanism for privatization addressed one very important problem. Because there was little legitimate cash with which companies could be purchased, the use of cash was likely to encourage outside purchasers, the provenance of whose funds would raise questions, or to facilitate schemes devised by associations and others to maintain control, or to lead to a combination of the two.

We have already noted that voucher tradability proved to be controversial. The 1991 law talks of “privatization accounts”. Some, not least Ruslan Khasbulatov, the chairman of the Supreme Soviet, felt that the presidential decree which made the voucher tradable had frustrated the intent of the law, and that the subsequent sale of vouchers at low prices had brought the Privatization Programme into disrepute.17 However, it is difficult to know what advantage could have been gained from privatization accounts, or indeed how they could have been used in the purchase of shares and/or of funds. If the shares that were to be bought were to be tradable, it is difficult to see why the vouchers used to purchase them should not be. And certainly, if the aim was to create strategic investors, the tradability of vouchers would help in this regard.

Only one voucher was issued to each citizen. It was given a face value of 10,000 roubles. The effect of this was that, unless they gave their voucher to an investment fund, individuals could only buy shares in one company, which could hardly be considered a sensible investment strategy. It also created some technical problems in workers’ subscriptions, since it was envisaged that if the subscription was oversubscribed, excess funds would be returned to the workers. This, of course, would be impossible if the subscription had been by way of vouchers, since it would be impossible to return a fraction of a voucher to a worker.18

In effect, individuals had limited choice as to how to use their voucher. Either they could use it in a workers’ subscription organized through their enterprise. About 30–35 million vouchers appear to have been used in this way.19 Alternatively, they could subscribe to a voucher fund which would buy and manage shares on behalf of many individuals. This structure of shareholdings is typical in the West, and was favoured by the reformers. By 1994, about 640 voucher funds had been established and some 40–45 million vouchers had been subscribed by around 20 million individuals. The three largest funds each had more than 8 million vouchers.20 The option of subscribing individually to one enterprise would have been quite a daunting process for a Russian with little knowledge of what those shares would cost, and what rights and value would be likely to attach to them. Many chose to sell their vouchers.

One repeated criticism of the Privatization Programme was that it was unfair in terms of the rewards it offered. And certainly, Chubais’s prediction that a voucher would be worth the value of two cars proved to be very far off the mark indeed.21 However, there were issues of fairness between those who were the workers in privatizing companies and the rest of the population. There were also issues of fairness between workers in different companies, with some workers’ shares being worth many tens of times those of other workers. And a similar observation could be made about managers, albeit with much higher upside stakes involved.

The aim of vouchers had been to ensure that everyone benefited from privatization. In parliament, the main opposition to privatization was not that companies should remain nationalized, but that they should, in the Soviet tradition, be given to the workers (Appel 2004: 84ff.). Chubais countered this argument by advocating that all citizens should benefit. The argument was not just about equity; it was about who would become the owner of Russian industry in the future. Worker/manager control was seen as a conservative force, inimical to the restructuring that would be necessary to make the Russian economy efficient. However, as discussed in the paragraphs above, the key goal of managers was to ensure stability and to retain control. The preferential terms on which workers could subscribe to shares gave ample scope for managers to ensure that enterprise insiders stayed in control. On average, about 20–25 per cent of vouchers seem to have been subscribed by workers and managers.22 By using these, and by raising cash, it is estimated that by 1994 they held 65 per cent of the shares in privatized enterprises; managers were likely to have held some 25 per cent and workers 40 per cent of these shares. The 116 million vouchers that were tendered at auction received around 20 per cent of the equity.23 So the programme was very advantageous for the workforce when compared to the rest of the citizenry. However, it is unlikely that many workers appreciated that benefit, as there was little change in the behaviour of the company of which they were now the owners.

The value of privatization benefits varied greatly between workers in different companies, depending on the number of workers and the competitiveness of the enterprise. Given the lack of competitiveness of Russian companies, shareholdings were unlikely to be of immediate financial benefit. But many workers would not have seen them that way. The point of owning shares in one’s own company was to stay in control, not to reap a capital gain. Nevertheless, the difference between the benefit accorded to a worker at Gazprom or Lukoil, which became part of the voucher programme in 1994, and that of a worker in an average Russian company was very considerable.

There were also anomalies. One story, whose reliability cannot be checked, is of the janitor of a research institute in St Petersburg, where others had objected to privatization and boycotted the auction. At the subsequent sale, the janitor’s was the only voucher tendered, and hence he became the owner of the enterprise. The technical issues associated with vouchers were considerable. During the period of privatization, Russia went through a major constitutional crisis, and relations between the centre and the regions were deeply strained. In this context, vouchers were expected to be distributed fairly; they needed to be available in time for the auction of companies; those company auctions had to be known about so that investors could buy the shares on offer, and vouchers had to be successfully cancelled after use. Broadly speaking this appeared to happen. However, the ease with which things could have gone wrong is perhaps best illustrated by an anecdote told by Dmitry Vasiliev.24 During the confrontation with parliament in October 1993, offices around the parliament building were occupied, and in many cases their contents ransacked or stolen. One office contained millions of vouchers belonging to voucher funds, placed there as collateral for their bids at voucher auctions. Apparently they were not in a safe. Had they been discovered and distributed, this could, according to Vasiliev, have undermined the entire privatization programme.

Implementation on the ground

There were substantial issues related to the implementation of privatization in the different regions of Russia, reflecting in part the uncertain constitutional settlement between the centre and the periphery. During 1992–94, the Consortium sent representatives to selected regions to assess their progress. Two recollections from senior western consultants give a sense of the different approaches to be found and the role of the local administrations in determining what actually happened on the ground. Like many events in Russia at the time, they reflect the pervading chaos which led to situations that were highly unusual. They are included in full in Appendix 4 below.

The first was from an investment banker employed to help with the auctions in Smolensk, a region that was generally deemed to be progressive. Even here, the local officials kept things close to their chest:

We … were bemused to find ourselves kept generally at arm’s length from the auctions themselves… . We received detailed reports of the outcomes after the event. The official in charge of these … was a master of stone-walling impassiveness… . We asked a Russian member of the team to investigate what was really going on and he soon confirmed that the process in Smolensk was similar to that being reported elsewhere. The general directors of many of the firms being auctioned had bought or bartered vouchers from their employees so that by the time the auctions took place, they (and/or their family and friends) could bid for a controlling stake.

A similar picture emerges from other regions. Novosibirsk is one example. The consultant sent to that region again noted that local officials were very much in charge of the process. The resulting ownership structures were therefore not only determined by the law, but also by who was in control.25

The temptation for local officials to take over the privatization process was aided by the lack of legal clarity about who was in charge and for how long. In Chapter 2, we discussed the ambiguities about who was in control of privatization. These continued throughout the period. The GKI was led by reformers and reported to the president, with its local agencies being granted the right in law to “effect privatization”. On the other hand, the Property Fund reported to the legislature and was the sole vendor of enterprises. Even as late as the autumn of 1992, there was no timetable for privatization beyond November, and it was unclear whether the GKI would remain in charge of the process beyond that date.

Given the political debates raging at the time, there was little certainty about how long privatization would last. Even if it continued, it was not immediately clear what assets would be privatized. As we discuss below, Russia was experiencing constitutional turmoil in which the powers of president and parliament were disputed. Throughout the period 1992–94, parliamentary opponents threatened to derail privatization. When Gaidar resigned in December 1992, there were concerns that the process would be reversed by Chernomyrdin, who had previously been particularly critical of the programme. The powers that were accorded to the GKI were time-limited and extended on an ad hoc basis. They were, in any case, dependent on a bottom-up process initiated and framed by enterprise directors.

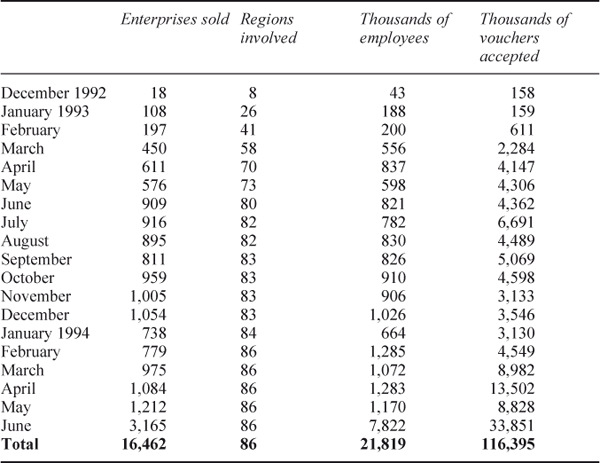

Despite this, as Table 4.1 illustrates, privatization took place with continuous momentum. Table 4.1 shows that voucher auctions proceeded uninterrupted between the spring of 1993 and June 1994. Indeed, there was a jump in auctions in that final month, which we discuss below. These auctions took place in a period of extraordinary political turbulence, as illustrated in Table 4.2 at the end of this chapter. By the time Yeltsin won the referendum on economic reform in April 1993, 70 out of Russia’s 86 regions were already participating in voucher auctions. These continued unabated during September and October, and were not halted by the return of a conservative parliament in December of that year.

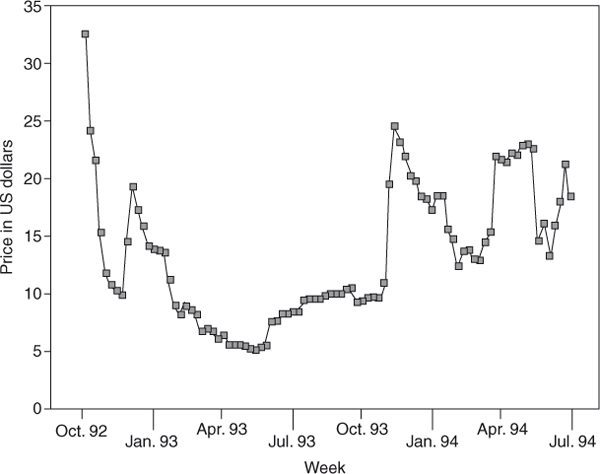

Table 4.1 Outcome of voucher auctions

Source: Blasi et al. (1997: 192).

Note

Some of the figures may contain dual counting, if an enterprise had more than one auction.

What was being sold and how?

Not only were there questions regarding who was in control of the privatization process, there were also questions related to the time frame of the Privatization Programme, as well uncertainty regarding what companies were to be included in the privatization. More broadly, there were issues about what value a share in a company could have when the legal and political situation was so uncertain.

In early 1992 reformers had in mind that there would be waves of privatizations. The 1992 Programme was to be the first of these. As it became clear just how challenging the timing of the programme was going to be, and how difficult it would be to agree a second wave of privatization, the period of validity of vouchers was extended. More controversially, at the end of the programme, companies that might be thought to be excluded from privatization were included within the scope of voucher auctions. So, for example, in March 1994, it was announced that Gazprom and Lukoil were to be included despite the fact that natural resource enterprises were expressly excluded from the Privatization Programme.

In any well-organized capital market, such changes to a programme of company sales would be unthinkable, not just because of its questionable legality but also because it would make the pricing of securities nearly impossible. So, for example, the value of a voucher depended on the value of the companies being sold, since the total value of vouchers and the total value of the shares purchased with them would need to equate. Further, those willing to use insider information could make considerable gains. For example, someone with knowledge of the fact that there would be “late entries” to the Privatization Programme could take advantage of the likely price spike that this would cause at the end of the programme. Doubtless, many did just that, since there was, of course, no effective law to prevent them from using insider information.

But in the extraordinary chaos of 1993–94, such criticisms might have been considered niceties. Privatizers would have pointed out that, throughout 1993, the entire programme was in danger of being derailed. In parliament they were debating an Option Four which would have given still more rights to workers and managers; in October the same parliamentarians attempted a coup against the President. Opponents of the privatization, on the other hand, would have said that the actions to introduce new companies to the privatization were simply illegal, as they were in breach of the programme parliament had passed. Both had a point. In the context of Russia in the early 1990s considerations of insider trading26 and similar abuses, which would today create outrage in developed western capital markets, were considered of comparatively minor significance. That level of disorder meant that the benefit of being a shareholder in a newly privatized company was not immediately clear. This is perhaps best illustrated by voucher prices. Each voucher had a face value of 10,000 roubles and, in closed worker/manager subscriptions, could be exchanged for equity of that book value. When used in open tenders, the value of the voucher was equal to the value of the shares it could purchase. Therefore, the aggregate value of the vouchers was equal to the aggregate value of the shares that were to be included in the Privatization Programme. Figure 4.1 tracks the value of the individual voucher.27 It can be compared with Table 4.2. So, for example, when the reformers lost political momentum, one would expect voucher values to fall, and, contrariwise, during periods when privatization appeared to be on course to continue with new assets being added to the programme, values would be expected to rise. Surprisingly, Figure 4.1 is insensitive to political events. For example, there was little change as a result of Yeltsin’s referendum victory in April.

But, starkly, at no time does the total aggregate value of the voucher programme equate with the true value that would be represented by full equity ownership of the companies whose securities were for sale. Vouchers varied in value from a low of about $5 to a high of around $20. So the entire voucher programme was worth between $750 million and $3 billion. In 1992, this would be equivalent to the value of a single company in the West. Admittedly, only 20 per cent of the equity of privatized companies was sold at auction, with 116 million vouchers thus tendered. Even so, that would suggest the total value of Russian enterprise equity to be worth between about $3 billion and $11 billion, a trivial sum for companies employing 22 million people.

In part, this low value may be attributed to the lack of available savings to buy vouchers and, thus, companies. In part, it can be attributed to the fact that many Russian enterprises were simply uncompetitive and, hence, valueless. However, the main reason for these low values must surely be attributed to the fact that ownership of equity in a Russian company conferred only modest property rights. To be a minority shareholder in a manager/worker-controlled enterprise was of limited value, particularly where there are few laws conferring rights or courts in which they can be enforced. So while privatization, and the issuance of shares, may have been a necessary condition for the exercise of ownership rights, it was very far from a sufficient one. In 1992–94, few would have believed that, even if they had a controlling interest in a Russian company, this would have allowed them to close it down, or to liquidate its assets, as would be possible in the West. Therefore, the Privatization Programme did not sanction a “new” set of owners, in the sense of selling the legal right of control. At the beginning of the programme, in October 1992, Chubais had said, “property in this country belongs to whoever is nearest to it” (Steele 1994: 310). Perhaps privatization did not change that very much. But it did establish de jure what was happening de facto, and favoured the interests of enterprise insiders over those from the old ministries who controlled the associations. It provided a first stepping stone for Russia to establish ownership on the basis of the rule of law.

What was achieved?

Indeed, given the confusion of events, laws and institutions in Russia at the time, comparisons that talk of “privatized” or “not privatized”, and that ascribe “ownership rights” without understanding the social and legal context within which these rights were granted, are unlikely to give an accurate picture of what was attempted and what was achieved, or of the difficulties that needed to be overcome.

By 1994, 16,000 companies had been created in Russia. In theory, all of them were supposed to have tradable shares. That would have meant that Russia, a country in which a few years earlier all private sector activity was illegal, would have created more than twice as many publicly traded companies as the USA, Japan and the UK combined. Further, this was going to take place in a period of hyperinflation. There was no precedent for the creation of capital markets in a hyperinflationary environment.

Indeed, the whole system of trade and exchange was under deep stress. Companies were trading on barter. The banking and payments system had collapsed – in part because enterprises were no longer profitable, in part because the bank clearing system had collapsed, and in part because the market created a proliferation of enterprises and banks – but there was no system of payments that responded to these new demands. However, the Russian government proved incapable of organizing an effective response to this crisis.28

In the meantime, new financial institutions were being established. However, the necessary underlying legal structures were not in place. Those operating in western financial markets are well aware of the complexity of the regulation necessary to ensure that financial institutions behave properly. New banks were established in Russia during the period of privatization. Investment funds were created. Both allowed their managers to access cash without the need to generate a profit. A cursory analysis of how the “oligarchs” made their early start suggests that these sorts of activities proved to be a more fruitful breeding ground than the take-over, even at a discount, of the industrial companies, which were the core of the Mass Privatization Programme.29

In summary, though by July 1994, 16,000 enterprises employing 22 million people had been transformed into corporate entities with shares, the number of their shares sold to outsiders was no more than 20 per cent of the equity. The majority of the shares were in the hands of managers and workers, whose main objective was to preserve the status quo. Thus, privatization was going to have a limited effect on reforming the economy. Certainly it managed to help establish ownership, although it did not put an end to the many devices by which managers could use or abuse their position. It did little to encourage restructuring; the new owners were likely to be very conservative in this regard. It did not raise money for the government or for the companies. It did not succeed in creating competitive markets; indeed, against the prescriptions of what would be taught in an introductory economics course, it allowed the creation of a vast number of private monopolies. And, while they may have been privatized companies, they were not capitalist ones in the sense that the government remained the main source of capital. Noting these limitations, the extraordinary plaudits received in the first half of the 1990s by the programme, described in Chapter 1, should be taken in a mainly political context. The rights of “ownership” conferred under the Privatization Programme had actually gone to those who were least likely to support the restructuring of industry. For the long-run development of the economy, the reformers had achieved an extraordinary victory. But for the short and medium term, the victory was Pyrrhic in that the new owners were likely to be opposed to the rapid restructuring of industry.

Indeed, the behaviour of Russian companies in the post-privatization period reflected the motivation of their new owners. They did not restructure in a way that would have been expected of a private company in a market economy. All companies faced an acute liquidity squeeze; the GNP had dropped precipitously. A private company would have cut costs, including labour. Indeed, that problem was considered so acute that some advisers recommended that the programme be slowed. In 1992, Sir Alan Peacock and Michael Hay led a UN Mission to Russia to advise on “how a suitable social policy might be devised to accompany the changes associated with the move to a market economy” (Hay and Peacock 1992: 60). They concluded: “There is one thing upon which Western experts and senior Russian ministers are in complete agreement. That is, that unemployment will become perhaps the major economic, social and political problem in the decade ahead” (ibid.). They went on to quote Jacques Attali, then President of the EBRD, who referred to “the potentially explosive problem of unemployment”.

Although economic conditions in Russia in the early 1990s were grim, there was no resulting mass unemployment in the short run. In large measure, this was because Russia was not a market economy. And those who owned its newly privatized companies were not private profit-maximizing owners, but workers and managers whose motivation was to stay in control in a deeply hostile environment. The 1992 legislation allowed them to do so. Perhaps as a result, unemployment did not immediately become “the major political, economic and social problem”. Had it done so, the consequences could indeed have been traumatic.

Writing before privatization took place, the Consortium observed that

if there has been a 25 per cent historic fall in production, 20 per cent over-employment and 20 per cent company bankruptcies, this would suggest that over 50 per cent of the industrial workforce could be laid off if privatised enterprises were to restructure in a way which reflected the motives of profit maximising market companies.

They went on: “unemployment should already be happening as a response to the fall in output, but it isn’t because the motives of Russian enterprises are different to those of their western counterparts. They retain labour.”

The 1992 Privatization Programme made little immediate change to that position. Had it done so, it would indeed have undermined political stability in Russia, and one can only speculate about the consequences The 1992 Privatization Programme was therefore a deeply conservative reform in the sense that it did not trigger radical change.

However, that does not mean that it was uniform, or indeed negative, in its effects. Commentators sometimes talk as if the managers of the companies hoodwinked the workforce, managing the companies for their own private benefit. In fact, the lack of layoffs suggests that they gave considerable weight to the interests of the workforce. Such would have been the tradition of Soviet management.

Indeed, there were instances where members of the workforce used their shares to change the management. One example would be the tractor works in Vladimir where Josef Bakalenik stood and was elected as general manager of the factory, in a contested election against the incumbent. Bakalenik had previously served as the enterprise’s finance director, and was one of the first Russians to have graduated from Harvard Business School. His election was supported by an investment fund, but the deciding votes were with the workforce.

It could be argued that in Vladimir one insider replaced another with the support of the workers and external investors. Evidence suggests that there was considerable resistance to uninvited intervention by outsiders. For instance, in 1996, USAID commissioned a programme of support from western consultants to assist eight Russian companies in restructuring. All companies were concerned about outside investors attempting to buy shares and, where this was felt to be a particular threat, they had set up systems to buy back their own shares, despite the fact that many were suffering from severe liquidity constraints. It is yet another irony that the issuance of shares, which should have served as a device that would allow companies to raise more capital, had in fact resulted in some of them feeling they had to spend their money to buy back their shares in order to stay in control.

The 1992 voucher programme came to an end in June 1994. On paper, the transformation was huge. In reality, the framing of the law, and the choices made in its implementation, meant it was a conservative reform. Factory managers and employees, who had been gaining increasing de facto power over the previous few years, gained de jure ownership. Yet they were still beholden to the state for access to capital and to nationalized enterprises for energy and power. A competitive market infrastructure and an enforceable code of law were yet to be put into place.

And, despite the October 1993 showdown between President and parliament, a consensus on the direction of economic reform had not been achieved between those two bodies. No clear path existed for the direction of a broader economic reform. There was no agreed programme for future privatization, and indeed parliament opposed any further privatization taking place. Nor could the terms of the 1992 Programme readily be repeated for the enterprises that might yet be privatized, such as the utilities and the natural resource companies. It would have been inappropriate to offer such valuable assets for sale with similarly generous terms to the management and workforce. Further, political storm clouds were gathering. Yeltsin would be up for election in 1996. The economic collapse of the country and his own failing health were hardly helping his electoral popularity.

Like a walker who has decided to cross a river on stepping stones, the reformers found they had taken one or two steps but remained precariously balanced, and it was far from clear how the reform process would unfold.