6 A bonfire of illusions

The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.

Antonio Gramsci, Prison Notebooks

As the crisis hop-scotched over some of the fastest growing economies in history, in a cover story in 1999, Businessweek predicted the emergence of a new ‘Atlantic Century’ (Warner et al., 1999). Despite the unwarranted substitution of the geomancy of one ocean for the geomancy of another in prognostications for the future, it underlined the extent to which bankruptcies and foreclosures had devastated the institutional fabric of the once-miraculous economies on the Asian rimlands and undermined the class coalitions that had ensured relative social peace in an era of breakneck economic growth.

Portraying the economic collapse as a financial crisis, the IMF mandated that governments of the economies placed on its life-support systems hike interest rates to stabilize their currencies, liquidate insolvent financial institutions, ensure central bank independence with price stability as its prime objective, open up capital markets and remove restrictions on the operations of foreign corporations including the right to engage in hostile takeovers (International Monetary Fund, 1997a; International Monetary Fund, 1998; Palat, 1999: 32–8; Bernard, 1999: 198–9). By applying the same recipe it had prescribed during the debt crisis of the 1980s to Latin American economies, the IMF ignored the very different configurations of production structures and class alliances and conflicts in the several economies along Asia's Pacific perimeters. Even Henry Kissinger observed that the IMF was like ‘a doctor specializing in measles [who] tries to cure every illness with one remedy’ (quoted in Cumings, 1999: 18). Rather than providing a tourniquet to stop the currency hemorrhage, the Fund's inappropriate diagnoses, prescriptions, and remedies aggravated the currency outflows and intensified the crisis.

In the first instance, by attributing the crisis to imprudent financial practices, lack of transparent accounting practices, and ‘crony capitalism,’ the IMF signaled that economic recovery would occur only after these deepseated problems had been tackled. This led to a stampede as investors sought to pull their capital out before it was too late and the IMF's insistence that economies hooked up to its life-support systems liberalize capital controls facilitated this capital flight. In this sense, the money transfusions provided by the Fund were really a bailout for the overseas bankers who had lent money to industrial enterprises and financial institutions in East and Southeast Asia (Stiglitz, 2002: 95–7). Additionally, by highlighting loose financial and accounting practices in the debtor countries, the IMF exonerated the lenders from all blame (Radelet and Sachs, 1998).

The suggestion that economic ‘fundamentals’ were suspect in the ailing economies also contributed to the crisis in South Korea, where it was triggered by banks refusing to rollover short-term loans. The IMF's demand that governments accepting transfusions of money and loan guarantees raise interest rates from 25 to 50 percent to stem the currency hemorrhage further hollowed out some of the most enterprising enterprises in history. When the won had reached historic lows against the US dollar, the IMF's insistence that the South Korean government increase the ceiling on foreign equity ownership from 26 percent to 50 percent by the end of 1997 and to 55 percent by 1998 and eliminate all restrictions on foreign ownership of banks made South Korean companies potential bargains for foreign corporations (Palat, 1999).

Finally, unlike the debt-crisis of the early 1980s when loans had been incurred by governments, in the economic crisis engulfing the Asian rimlands in the mid-1990s, loans had been incurred mainly by private enterprises. In these circumstances, by imposing conditions on governments, the IMF's rescue program led to the nationalization of private corporate debt. Demands for draconian cuts in government expenditure including the privatization of state-owned enterprises and elimination of subsidies on essential items in states without well-developed social security nets severely weakened aggregate demand. The wave of bankruptcies, joblessness, and currency turmoil submerging these economies implied that intra-Asian trade which had accounted for 53 percent of all Asian trade in the early 1990s could no longer be the motor for regional growth and recovery and the whole regional edifice began to unravel at a dizzying pace (Bello, n.d.; Bello, 1998b: 15). Estimates suggest that Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea, and Thailand suffered import declines ranging from 30 to 40 percent in 1997. Almost three years after Thailand was caught in the economic riptide, it was reported that less than one-third of the 2.5 million Thais who lost their jobs had received any kind of compensation (Crispin, 2000). In Indonesia, the number of unemployed was officially estimated to have increased from 13.7 million at the end of 1997 to 27.9 million at the end of February 1998 and some 79.4 million, or 40 percent of the population, were reckoned to be below the poverty level by early July 1998 (Robison and Rosser, 2000: 171–2; see also Stiglitz, 2002: 97, 99, 121).

The high growth rates registered by these economies, before the collapse of the baht sent their currencies into a free-fall, magnified the impact of the sharp turnaround in their fortunes. South Korea's per capita growth rate fell by almost 15 percent in 1997–98, Malaysia's and Thailand's by more than 20 percent, and Indonesia's by about 25 percent:

Sudden collapses of these orders of magnitude… [had] no parallels in these countries' own histories. According to Suk Bum Yoon, some Koreans believe that the pain and economic loss associated with the crisis was worse than those experienced during that country's traumatic civil war of 1950–53. The convulsion in Indonesia during 1965–66, which led to the emergence of President Soeharto's socalled New Order regime, were associated with a decline of economic growth of no more than 2 percent of GDP…. Thailand had not experienced a year of negative growth since 1960. Malaysia's last recession, of 1985–86, saw negative growth of no more than 2 percent.

(Hill and Chu, 2001: 6)

The breathtaking velocity and intensity of the meltdown mercilessly exposed the rifts in the social coalitions underpinning the developmental state that had been camouflaged by the fevered pace of growth in the pre-crisis years. If the Japanese government had been able to compensate for the retraction of corporate investments after the Japanese bubble burst in 1990, the smaller economies caught in the cascade of currency values and unsustainable levels of corporate debt had no such options. Even the resources of the Japanese government, strained by years of budgetary deficit, were insufficient to bail out insolvent banks, financial institutions, and industrial enterprises.

As social actors jostled for advantage, bureaucrats and opposition politicians in some jurisdictions initially welcomed IMF intervention since it provided opportunities to implement measures that had hitherto been politically unfeasible and because it could potentially prise open corrupt and authoritarian structures of government. More importantly, as the crisis wreaked havoc on corporate structures and massive layoffs undermined the power of organized labor, the implementation of policies force fed by the IMF to the governments of the ailing economies also changed the relative balance of forces between governments and enterprises. If it was the transborder expansion of corporate networks and the ensuing anachronism of regulatory controls that had led to conditions of overproduction, the nationalization of private corporate debt and the infusion of public funds to stabilize financial institutions conferred a great degree of relative autonomy on state apparatuses in several jurisdictions. With the signal exception of Indonesia – where the combination of a resurgence of ethnic and religious rivalries with the implosion of the federal government has made political fragmentation a real possibility – after an initial phase of disarray, governments in the region have begun to institute regional mechanisms not only to blunt the impact of speculative attacks on currencies but also to jumpstart economies along the region without relying on the United States as a market of last resort, as we shall see in the Epilogue.

In the first section here, we will chart the impact of the crisis and the ongoing processes of restructuring that wreaked havoc on corporate structures all across the Asian rimlands: keiretsu structures loosened and even unraveled, the chaebol were dismembered, mergers and acquisitions saw the wholesale transfer of corporate assets to overseas investors in some locations, the relentless transfer of production overseas hollowed out industrial sectors in the ‘dragons’ and many neighboring economies. Worsening economic conditions also undercut the power of labor and where structural collapse had not fatally compromised centralized government control – as in Indonesia – the weakening of major social classes once again conferred a degree of autonomy on the state apparatus, albeit on a basis far different from the developmental states of the Cold War era. The greater role of the state was underlined when the Hong Kong administration fended off speculative attacks on the Hong Kong dollar by spending some US$15.2 billion in the acquisition of stocks and became the single largest shareholder in the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation in 1998. Subsequently, as we shall see, the Tung Chee-hwa administration adopted plans to transform the Special Administrative Region into an innovation-led, technology-intensive economy – adopted, that is, the functions of a developmental state (So and Chan, 2002). Bluntly put, while the IMF seized the crisis to excoriate activist state intervention, its own prescriptions have ironically strengthened the ability of governments to intervene along the Asian rimlands.

If the headlong descent of the Asian ‘miracle’ economies in 1997 and 1998 led to a retrospective indictment of administratively guided industrialization strategies by international financial institutions and Western governments, the compression of export prices from the ailing economies adversely impacted on manufacturing profits in the United States and Western Europe as we shall see in the second section. While constraints of space preclude a detailed analyses of these economies, even the thumbnail sketches presented here indicate that neither the United States economy nor the European Union were strong enough to pull the world economy out from the deepening recession. Though equity prices became hugely inflated in the United States, this asset-price inflation was not accompanied by a strong growth in production or profits and accordingly led to sharp falls in equity prices since mid-2000. Meanwhile, the costs of German reunification and difficulties entailed by the creation of a common currency had sapped the vitality of the European Union. If the relentless rise of stock prices in the United States had led to an influx of capital – especially from the Asian rimlands where the IMF's conditionalities eased capital flight – the collapse of the speculative bubble facilitated a reorientation of macroeconomic policies in East and Southeast Asia that may lead to an economic revitalization – a possibility we shall explore in the Epilogue.

A brave new world

In analyzing the ongoing restructuring of power relations in Indonesia, Vedi Hadiz (2001) aptly invokes Lenin's acute insight that a revolutionary situation arises only when two conditions are satisfied: the refusal of new forces to continue living in the old way and the inability of dominant classes to continue asserting their dominance. The tragedy of rapid economic growth along Asia's Pacific coasts was that while the developmental state had been rendered anachronistic by the trans-border expansion of production and procurement networks, embryonic new social forces remained unable to dislodge the post-Second World War social order. Regional economic collapse cast into sharp relief all the problems – the changing balance of class forces, tensions associated with increasing inequalities in income and wealth, the greater prominence of industrialists of Chinese ancestry in several jurisdictions, as well as social dislocations caused by migrant labor, and environmental degradation (Pempel, 1999a: 225) – that had hitherto been submerged by the breakneck pace of growth, just as policy options for governments became tightly constrained and the end of the Cold War meant that the United States had no incentive to prop up authoritarian regimes.

As the crisis impacted unevenly across Asia's Pacific Rim, the restructuring of political economies was conditioned by the specific constellations of power and privilege in each jurisdiction. Though Thailand and South Korea were pressured by the IMF into accepting greater foreign ownership of their corporate assets, the Thai government increased its stake in the banking sector while capitalists based in new sectors exploited opportunities presented by the eclipse of banking capital to transform power relations between capitalist factions. The reformist government in South Korea used the IMF conditionalities to undercut the power of the chaebol and organized labor with some success. In Indonesia, though, initial resistance by the Suharto regime and the weakening of central authority led to a far more anarchic situation while Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir was able to evade IMF guidelines altogether by imposing capital controls in defiance of the Fund. Exposure of Japanese banks to large losses not only led to a spate of bank failures and takeovers by foreign interests but also to a thorough-going transformation of industrial organization. If government control of the commanding heights of the economy enabled Taiwan and Singapore to withstand the meltdown of neighboring economies, the serial transfer of manufacturing facilities to China increasingly jeopardizes Taiwan's industrial structure. Faced with a similar hollowing out of the industrial structure of Hong Kong, its government has even formally abandoned its laissez faire policy in favor of strategic economic planning. We examine these patterns in more detail below before turning to the impact of the Asian crisis on economies in Western Europe and the United States in the next section.

The most emergent arena of restructuring was the banking sector where financial liberalization had exposed the weakness, inexperience, and downright backwardness of banks all across a region where manufacturing, rather than finance, had occupied center-stage. Though Japanese banks were among the world's largest by market value, they lagged behind European and American banks in computerization and risk and asset management strategies. The most profitable Japanese banks earned a 2 percent return on equity compared with the 10 to 20 percent earned by their Western competitors. Some of the largest banks did not even have investment banking operations while others were without retail banking arms. Unlike American and European banks, the association between industrial enterprises and ‘lead’ banks meant that Japanese banks also rarely made syndicated loans to corporations to spread the risk (Kahn, 1999).

Insulated from foreign competition, able to freely access capital from world financial markets, and unbound by cash reserve constraints imposed by regulators elsewhere, banks represented a virtual gold mine for influential families especially in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. Hence, some bureaucrats and opposition leaders welcomed international pressure for providing a politically convenient cover to implement some long-needed changes, and to selectively punish opponents (Murphy, 2000; Bernard, 1999). John Matthews (1998: 752–3) even suggests that some elements of the IMF's stabilization package – relating to restructuring of the chaebol, and the institutional separation of the Bank of Korea from the Ministry of Finance – were instigated by South Korean bureaucrats themselves.

Even in Malaysia, where the central bank had greater autonomy from influential families and the personal interests of the political leadership were not so intertwined with the fortunes of particular institutions, attempts to exercise discipline over banks had largely been ineffective until the crisis set in. The economic meltdown, at the same time, triggered a confrontation between Prime Minister Mahathir representing what Edmund Gomez and K. S. Jomo (1997) have called the ‘politicized oligopolies,’ and his anointed heir, Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, representing technocrats, small businesses, and sections of the Malay and non-Malay middle classes. The latter attributed the crisis to nepotism and lack of transparency and supported the IMF's recommendations for higher interest rates, fiscal restraint, and currency stabilization as a restoration of ‘economic fundamentals.’ However, the former saw higher interest rates and further economic liberalization as the path to transferring national assets to foreign owners and viewed with alarm the experiences of South Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia after they had been subject to the IMF's ministrations. Most notably a wholesale accession to IMF demands would have cracked the social compact that had preserved inter-ethnic peace for three decades and Mahathir's ability to play the nationalist card and prevent large-scale unemployment helped him triumph over his former deputy.

Defying the IMF, Mahathir sought to stem the currency hemorrhage by reimposing controls in August 1998 over capital flows, pegged the ringgit at 3.80 to the dollar, cut interest rates, decreed that all offshore ringgit be repatriated by the end of September, and declared a freeze on the repatriation of overseas portfolio capital for a year. Despite condemnation from the IMF and US Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin – and the resignation of Malaysian Central Bank governor, Ahmad Mohamed Don and his deputy, Fong Weng Phak, in protest – these measures reversed the tide and capital controls were rolled back within twelve months. Rather than retreating to an insulated economic environment, these regulations were designed to severely restrict currency speculation and did not expose Malaysia to the ravages experienced by states which were subject to the IMF's ministrations. In this endeavor, Mahathir was aided by the Japanese government – still smarting after it was forced to shelve its proposal for an AMF – guarantee of $570 million in Malaysian government bonds in December 1998 (Wade and Veneroso, 1998b: 21; Stiglitz, 2002: 123–5; Hughes, 2000: 222).

Simultaneously, Mahathir launched a restructuring plan that was carefully calibrated to punish his opponents and to maximize electoral mileage for the ruling party. After sinking some $15.8 billion in public funds to take over bad loans and recapitalize insolvent institutions, in August 1999, the government decreed that the country's 21 commercial banks, 12 merchant banks, and 25 finance companies merge into six ‘superbanks’ within a year. In mandating this restructuring of financial institutions, the government victimized institutions like Hong Leong and Phileo Allied associated with Anwar and mollified the Chinese by expanding the number of anchor institutions (Jayasankaran, 1999; Fuller, 1999).

By refusing to subject the economy to the ministrations of the IMF, unlike other ailing economies, Mahathir was also free to directly support a number of non-financial enterprises. However, once again political considerations loomed large, and while the state-owned oil company, Petronas, was enlisted to bail out the national car project, a number of companies with prior experience in the automobile sector were excluded from the project because these were owned by members of the Chinese minority (Gomez and Jomo, 1997: 180; Khoo Boo Teik, 2000; Haggard, 2000: 164–70).

For over a decade, as internal conflicts, mismanagement, and corruption plagued the Thai financial sector, successive governments had tried in vain to rein in the prominent families. The crisis finally helped corral them and by November 1997 the financial sector was almost completely transformed. Debt-for-equity swaps saw the virtually wholesale transfer of banking and financial sectors to American, European, Japanese, and Singaporean investors – by October 1998, one-third of the companies in the financial sector had been closed down and only five banks (Bangkok Bank, Thai Farmer's Bank, Bank of Ayudhaya, Siam Commercial Bank, and the Thai Military Bank) have survived with majority Thai ownership. Even so, by the end of 1999 total state investment in Thai banks approached US$12 billion, or almost 10 percent of GDP. The hollowing out of the banking and financial sectors propelled capitalists based in newer sectors to the top of the list of wealthiest families in Thailand, and Thaksin Shinawatra, the head of the wealthiest family, was elected prime minister in January 2001. His Thai Rak Thai (‘Thai Love Thai’) party won the support of all major big businesses and is seeking to get a breathing space by suspending reforms so that these businesses can regroup in the changed conditions of accumulation (McDonald, 2001; Hewison, 2001; Bello et al., 1998: 47–8; Arnold, 1999b; Hewison, 2000: 203–4).

There had been much greater resistance to restructuring in Indonesia because it adversely affected the interests of the Suharto clan. President Suharto's initial reluctance to agree to the Fund's terms spread apprehension among investors and even after the government accepted the stringent conditions attached to a $43 billion rescue plan, the rupiah continued its headlong descent. Between January 15, 1998 when the agreement between the Indonesian government and the IMF was reached and January 22, the rupiah plunged from 8,500 to the US dollar to 16,500. Such savage volatility in exchange-rates made a mockery of the agreement, which had been premised on an exchange-rate of 5,000 rupiah to the dollar. When the rupiah had been trading at 2,400 to the dollar six months earlier, the currency's fall was so drastic that only 22 of the country's 228 publicly traded companies had assets exceeding their liabilities (Mydans, 1998; Bremner, 1997).

An economic contraction of this magnitude – by the end of 1998 almost 50 percent of the population was below the poverty line (Hill, 2000: 264)1 – fueled ethnic tensions and re-ignited separatist movements that President Suharto's New Order Indonesia was ill equipped to contain. On the one hand, the cohesion and prestige of the military had been shattered by the exposure of its activities in East Timor and its role in fomenting anti-Chinese riots as well as by power struggles between the top brass. On the other hand, the insolvency of large conglomerates had undermined the social base of the ruling coalition while the heavy bias toward Java has spawned a variety of ethnic and separatist movements that might yet lead to the break-up of the world's fifth most populous state (Robison and Rosser, 2000).

The first manifestations of a rupture in the social order appeared in the form of brutal attacks on the Chinese minority. Unlike in Malaysia and Thailand, where Chinese minorities also controlled a disproportionate share of wealth, Sino-Indonesians were more vulnerable as they constituted a far smaller percentage of the population than in the other two jurisdictions. Hence, though a few prominent Sino-Indonesians had gained access to President Suharto's inner circle, the ruling Golkar party had not sought to integrate them into the power structure. In contrast, a variety of Islamic groups that had gained access to power sought to blame the wealthy minority for the crisis. Deprived of political cover, the Sino-Indonesian bourgeoisie sought to transfer funds overseas and thus aggravated the currency hemorrhage (Haggard, 2000: 116).

As the economic meltdown intensified, popular protests spearheaded by students but also manifested in the resurgence of militant separatist movements, eventually led to the fall of the Suharto regime after massive demonstrations rocked Jakarta in May 1998. Whatever else it might have connoted, the succession of Suharto's long-term confidante – Bachruddin Jusuf Habibie – to the presidency could not resolve the situation. Tied as the new president was to the New Order's elite, he could not uproot their privileges, while his own political survival demanded creating a space for new social forces thrown up by the crisis. Without Suharto's control over the military and government institutions, Habibie could not manage the accommodation of new social actors while preserving the scaffolding of the New Order. Precisely because 30 years of authoritarian rule had ensured that emerging social forces were not all equally well positioned in the ensuing contest for power, the erosion of centralized institutional frameworks was accompanied by the rise of coalitions of business and bureaucratic–political elites for power by creating competing networks of patronage. The breakdown of centralized political authority was also accompanied by the deployment of paramilitaries, directly or indirectly linked to political parties, as intra-elite groups sought to hijack democratic processes to feather their own nests (Tornquist, 2000; Hadiz, 2001).

By the time the government was able to seriously address the question of restructuring the banking sector after Suharto's ouster in May 1998, it was estimated that non-performing loans amounted to at least half of all outstanding credit and that most banks were insolvent. Compounding the situation, it became apparent that most banks had misrepresented their assets and hence overstated their ability to recapitalize. Government cash injections of some $10 billion implied that the government held 75 percent of the liabilities and 90 percent of the negative net worth of all Indonesian banks as over 66 banks were liquidated and 12 taken over by the state between September 1998 and March 1999 (Asian Development Bank, 1999: 25–7; Robison and Rosser, 2000: 185–8).

Despite plummeting asset values, bouts of political instability – such as persistent violence and the removal through impeachment of President Abdurrahman Wahid after he had maneuvered to succeed Habibie – meant that the tidal wave of foreign investments submerging domestic capital in the other ailing economies in the region has been conspicuously absent in Indonesia. This has enabled the elite to sell their non-performing assets at overvalued prices to the government and then buy them back at a heavy discount since there were no other potential purchasers (Hadiz, 2001). In Indonesia, therefore, while popular forces had dislodged centralized authority, they were unable to capture power and local ‘big men’ were able to step into the breach.

Conversely, there was less official resistance to restructuring in South Korea since the IMF mandates nicely dovetailed into the reform agenda of Kim Dae-Jung, the country's most famous dissident who had been elected president in the midst of the crisis. However, despite President Kim's predisposition to implement the IMF's plans because of his opposition to the chaebol, the better organization and strength of the labor movement and fierce resistance by heads of chaebol often stymied reforms. The insolvency of these conglomerates had catapulted financial restructuring to the top of the agenda and the government nationalized merchant banks with massive problem loans – spending some 115 trillion won ($117.3 billion) over four years to recapitalize the banks and other financial institutions – and then sought to liquidate, merge, or sell 15 of them. This opened the way for several overseas institutions to acquire a foothold in the country's financial system. Additionally, while separating the Bank of Korea from the Ministry of Finance, the government transferred oversight responsibilities to a new institution, the Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC), located within the prime minister's office. Finally, like the cases of Thailand and Indonesia, assets of shaky or insolvent financial institutions were transferred to a newly created Korea Asset Management Corporation (Strom, 1999; Matthews, 1998: 753–4; Larkin, 2002).

Plans for corporate reform proceeded in tandem with these measures. Medium-sized chaebol (those below the top five) were especially vulnerable due to their exceedingly high debt to equity ratios. Like their larger counterparts, these chaebol had also resorted to cross-subsidiary loan guarantees, cross-investments, and intra-group sales to expand and diversify their operations by borrowing with minimal collateral. Their greater inexperience and lower technical proficiency combined with their smaller size meant that the failure of one marginal affiliate could more easily jeopardize all other units, as demonstrated by the cases of the Kia and Halla chaebol. The government consequently used medium-sized chaebol as a testing ground for a raft of legislation which were then selectively applied to the Big Five. In the first instance, cross-subsidiary loan guarantees, cross-investments, and other similar financial arrangements were prohibited and internationally accepted accounting protocols were instituted. Ceilings on foreign investments were raised from 26 to 50 percent and the proportion of shares that could be acquired without board approval was increased to ease foreign takeovers and mergers. The government also strongly encouraged creditors and debtors to work out differences through arbitration, debt-equity swaps, extending terms for repayment, new equity issues, and other arrangements (Cumings, 1999: 26; Matthews, 1998: 750–1, 755–6; Woo-Cumings, 1999: 132–3). Market liberalization and the transfer of corporate assets to overseas investors is reflected in the rise of foreign investments from $1 billion in 1992 to an estimated $20 billion in 2000, all the more significant given the fall in the value of the won (Strom, 2000a).

Since the top five chaebol had lost their gilt-edged credit ratings, the government used the threat of cutting off credit to pressure them to streamline their operations by shedding loss-making subsidiaries and focusing on their ‘core competencies’ to retain their positions as internationallycompetitive enterprises. To dampen overproduction, the government negotiated a series of business swaps and mergers: Daewoo trading its electronics firm for Samsung's automobile unit, or the consolidation of the memory-chip manufacturing arms of Hyundai and LG to create the world's second largest manufacturer of DRAM chips after Samsung (Woo-Cumings, 1999: 133). Perhaps most strikingly, the government authorized Hyundai Motors to spin-off from the country's largest chaebol in August 2000 and Hyundai Heavy Industries in March 2002, reducing Hyundai to a small collection of distressed companies (Burton, 2000; Ward, 2002a).

Despite the winnowing of weak performers, economic recovery is still faltering. After almost five years of restructuring, in April 2002 several major conglomerates still had very high debt–equity ratios, as indicated by Table 6.1, and the earnings of almost 24 percent of the manufacturers listed in the Kospi share index were not enough to cover interest payments on their debts (Ward, 2003).

The South Korean government also used international pressure as a convenient cover to discipline labor. When workers had forced the Kim Young Sam government to rollback measures introduced to dilute employment security in early 1997, Kim Dae-Jung, backed by an IMF mandate, was able to do what his predecessor could not. The dismissals that followed tripled the country's unemployment rate – with the number of jobless workers increasing from 658,000 to 1,700,000 between December 1997 and December 1998 (Koo, 2001: 201–2; Cumings, 1999: 26–7; Bernard, 1999: 197–200). Unemployment and the threat of unemployment undercut the power of organized labor, as indicated by the failure of the Hyundai Motors strike in the summer of 1998, the Seoul Metropolitan Subway Workers’ Union the following May, and Daewoo Motors’ strike in February 2001 (Neary, 2000; Kirk, 2001a).

Early initial successes, including the swap of subsidiaries among the bigger chaebol, mergers and acquisitions, however, soon ran aground because the pride of the owners of these behemoths was tied to their expansion into certain prestigious sectors. The higher capital-intensities of South Korean enterprises also enabled small groups of strategically placed workers to cripple production, and when unemployment rates had reached 8.6 percent by February 1999, prospects of further layoffs led them to join chaebol heads in frustrating plans to allow foreign firms to acquire South Korean firms. A report issued by a government research institute, the Korea Institute of Finance, acknowledged that by 2001, the four largest chaebol – Samsung, LG, SK, and Hyundai – had allocated only 17.5 percent of their

| No. of affiliates | Debt-equity ratio (%) | Assets (000 billion won) | |

| Korea Electrical Power Corpa | 14 | 72.1 | 90.9 |

| Samsung | 63 | 240.6 | 72.4 |

| LG | 51 | 206.8 | 54.5 |

| SK | 62 | 156.4 | 46.8 |

| Hyundai Motors | 25 | 168.0 | 41.3 |

| Korea Telecoma | 9 | 101.7 | 32.6 |

| Korea Highway Corpa | 4 | 100.4 | 26.4 |

| Hanjin | 21 | 294.4 | 21.6 |

| Korea Land Corpa | 2 | 373.4 | 14.9 |

| Korea National Housing Corpa | 2 | 185.2 | 14.5 |

| Hyundai | 12 | 977.6 | 11.8 |

| Gumho | 15 | 503.1 | 10.6 |

| Hyundai Heavy Industry | 5 | 219.4 | 10.3 |

| Hanwa | 26 | 238.3 | 9.9 |

| Korea Water Resources Corpa | 2 | 27.2 | 9.5 |

| Korea Gas Corp | 2 | 256.0 | 9.1 |

| Doosan | 18 | 191.4 | 9.0 |

| Dongbu | 21 | 312.1 | 6.1 |

| Hyundai Oilbank | 2 | 837.1 | 5.9 |

Source: Adapted from Ward (2003).

Notes

a State-owned enterprises.

investments to their core companies (Kirk, 2001b). However, sharp falls in imports as well as a steep decline in the value of the won stimulated favorable trade balances, and by January 2000 the jobless rate had fallen to a post-1997 low of 4.4 percent (Bridges, 2001: 75–84).

Mired in financial doldrums since the speculative bubble burst in 1990, the deepening crisis along Asia's Pacific Rim revealed the full extent of problems in the Japanese banking sector and prompted the government to promote a thoroughgoing reform. Though Japanese banks had been able to cover up the extent of domestic non-performing loans by lending overseas, with Japanese banks holding some 37 percent of private external liabilities of the ‘newly industrializing economies’ in Asia,2 the collapse of East and Southeast Asian economies highlighted their lending practices. Intense pressure from international financial organizations, Western governments, and international investors, compelled the Japanese government to admit that potentially bad loans held by Japanese banks amounted to approximately ¥76.7 trillion yen or $583 billion in January 1998 – more than twice the previous estimate. By March 2001, a government report estimated that some $150 billion of this amount was fully unrecoverable (Tabb, 1995; Bennett, 1997; Leyshon, 1994: 134–5; The Economist, 1997e; Tett and Wighton, 1998; Chandler, 2001b).

Stretched as Japanese government finances were by high expenditures – by the end of 2001, the Wall Street Journal estimated that Japanese central and local government debt would account for 36 percent of global debt, or more than one and a half times the corresponding figure for the United States (McCormack, 200: xiii) – to maintain low rates of unemployment and to compensate for low rates of corporate investments, it was unable to prevent a spate of high-exposure bank failures. With the regional economic collapse tightening credit, Japan's oldest brokerage house (Yamaichi Securities) and two of the largest 20 banks (Hokkaido Takushoku and Tokyu City banks) collapsed in November 1997. At the same time, five of the top ten banks reported huge losses (Bennett, 1997; The Economist, 1997b), and the yen dipped to its lowest rate against the US dollar in more than five years. In September 1999, the venerable Long-Term Credit Bank – the primary vehicle through which the government had bankrolled postwar reconstruction – was acquired by New York-based Ripplewood Holdings L.L.C. Even before Ripplewood's acquisition of a toehold in the financial sector, the first time that foreign investors secured control of a Japanese bank, and to insure themselves against similar takeovers, Japanese banks began to combine forces. In August 1999, Dai-Ichi Kangyo (DKB), Fuji, and Industrial Bank of Japan announced their merger to create Mizuho Holdings, the world's largest bank with assets of ¥141,000 billion (US$1,257 billion). With other mergers, the consolidation of operations in the Japanese banking sector led to substantial declines in employment (New York Times, 1999; Sims, 1999a; Tett, 1999; Tett and Harney, 1999; Kahn, 1999; Sims, 1999b).

While there had been mergers in the Japanese banking sector before, the current wave is significant for several reasons. Under pressure from the government – which channeled some ¥7,450 billion in public funds to help 15 major banks resolve their problem loans in early 1999, and a series of supplementary budgetary allocations every year since then – to restructure banking operations, it is expected that these mergers will consolidate overlapping facilities and pool resources to develop more effective risk management and banking strategies, including the investment of up to ¥150 billion a year in systems technologies. This was in sharp contrast to previous mergers where there had been stiff resistance to consolidating duplicate operations, cutting staff and severing unprofitable alliances (Harney and Tett, 1999; Sims, 1999a; Sims, 1999b; Tett and Harney, 1999)!

Since companies in rival keiretsu were competitors, the merger of banks further eroded the close relationships between the banking and industrial wings of the group and may indeed undermine the whole structure of postwar industrial relations (Tett and Naoko Nakamae, 1999).3 Underlying this change, Japan's third-largest company by market capitalization, Toyota, listed its shares in the London and New York stock markets in September 1999 to increase its investor base and unwind the cross-shareholdings that had insulated Japanese companies from outside scrutiny (Nakamoto and Abrahams, 1999; Harney, 1999). Even more significantly, in March 1999, France's Renault acquired operational control over Nissan and subsequently Ford and DaimlerChrysler followed suit, acquiring control over Mazda and Mitsubishi Motors respectively. GM also increased its stake in Suzuki, Isuzu, and Subaru (Tanikawa, 2000).

These trends portend a further ‘de-territorialization’ of the techno-structures of Japanese corporations. As we have already seen, earlier waves of the cross-border expansion of production networks had either been spearheaded by Japanese small- and medium-scale enterprises, or parts suppliers had followed major manufacturers as they installed production facilities overseas. Especially after the collapse of the speculative bubble, the transnational expansion of Japanese capital had led to a loosening of keiretsu structures and jeopardized domestic multi-layered subcontracting networks. In the 1990s, as manufacturing shipments from Japan fell by 10 percent, some 20 percent of manufacturing jobs were eliminated and it is estimated that some 45 percent of manufacturing operations of Japanese multinationals occur outside Japan (Brooke, 2001a; Nakamoto and Pilling, 2002).4 The transfer of production overseas has serially reduced the large surpluses that the Japanese economy reaped from its trade with Asia, with its trade balance with China (including Hong Kong) turning into a deficit by 2000. The fact that more than half of the China–Japan trade occurs within Japanese corporations – as production is sourced out to subsidiaries and joint ventures in China to gain cost advantages – forcefully underscores the dissolution of ties that had bound large and small businesses (Brooke, 2001b). In Japan itself, year-to-year bankruptcies were 21 percent higher in July 2000 (Strom, 2000b).

Another strand in the strategy to revamp Japanese industry is indicated by Sony's decision to bring its camcorder production back to Japan from China in the summer of 2002. While it is too early to tell whether this is a harbinger of a more general trend, it does suggest the impact of digitization, which shortens product life cycles to three and six months and increases pressures to calibrate production volumes more closely to market demand and to reduce shipping times. Responding to these pressures, Sony revamped its manufacturing operations in Japan by replacing product-based groups with cell-based manufacturing. When the company makes 200 to 300 models of camcorders, producing them in small batches by small groups of workers enables Sony to respond more nimbly to changes in market demand. This is because it can exercise better control over the volume of production than previously as assembly lines are notoriously difficult to stop once they are set in motion. Underpinning the system was the creation of four Sony Engineering, Manufacturing, and Customer Service (EMCS) companies – one each for Japan, Europe, the United States, and China – which consolidated activities carried out by separate manufacturing companies. By consolidating its separate manufacturing companies that had hitherto been divided along product lines, it has streamlined supply chains and ensured the optimal allocation of resources between its product lines. For instance, factories producing television sets in Japan had their peak production periods in the spring and autumn to meet high market demand at the start of the business and school year in April and for Christmas, while their slack periods were in the early summer and early autumn, which were the peak production times for camcorders to meet high demands for the holiday season. By consolidating operations, Sony's EMCS companies could share their resources between different product lines more optimally. Indeed, Sony has so streamlined its operations that it can now deliver a product to the United States within 48 hours of the order being received and the company has even closed its warehouses in the United States and Japan (Nakamoto, 2003).

Industrial restructuring by large Japanese companies and the establishment of direct relations with foreign suppliers and customers was accompanied by a steady decline in their reliance on the sogo shosha. Complicating matters for the sogo shosha, since they had often provided financing for infrastructural development – oil exploration, gas pipelines, mining – connected with their commodity trade, falling raw materials prices saddled them with substantial debt burdens. At the end of March 2001, all six of the largest sogo shosha had high liabilities – Nissho Iwai's debt including off-balance-sheet loan guarantees stood at 2,170 percent of its equity, Marubeni's at 1,100 percent, Itochu's at 1,050 percent, Mitsubishi's at 510 percent, Sumitomo's at 500 percent, and Mitsui's at 460 percent. To reduce their liabilities, the sogo shosha have also begun to merge their trading operations – Nissho Iwai and Mitsubishi agreed to combine their steel-trading operations for instance, while Sumitomo Chemicals and Mitsubishi Chemicals negotiated a merger – and to slash jobs (Hijino, 2000; Belson, 2002).

Just as a rising yen led to a spate of Japanese takeovers of US companies in the 1980s, continuing asset-price deflation – the Nikkei average of Japanese stocks dipped below the 10,000 benchmark for the first time in 17 years on November 13, 2001 – led to a stunning 129 percent increase in foreign direct investments in 1999 as overseas investors bought up ailing Japanese firms. The number of mergers and acquisitions initiated by foreign firms similarly grew by a record 34.7 percent in 2000 (South China Morning Post, 2001b).5 Inflows of foreign investment grew by a further 30.3 percent in 2000 and US firms accounted for one-third of all foreign investments in Japan (South China Morning Post, 2001a). By another measure, the share of foreign firms in Japanese mergers and acquisitions in 2001 rose to one-third of the total volume – compared with 13 percent in 1999 and 2000 – and the Tokyo Stock Exchange reported that for the first time foreigners accounted for 51.8 percent of trading by value (Brooke, 2002; Ibison and Leahy, 2002).

Put differently, whereas Japan alone accounted for 45 percent of the global aggregate stock of market capitalization at the end of 1987 and the United States for 30 percent, by 1999 Japan's share had shrunk to 11 percent while the US share had increased to 52 percent (Clairmont, 2001; Tabb, 1999: 77–8). The closest contemporary parallel to the Japanese asset deflation, which the OECD estimates reduced the nation's assets by $8 trillion in the 1990s, is the parallel annihilation of Soviet assets. Japanese business debt is hovering at close to 97 percent of GDP and even after bad debts of ¥60 trillion were written off, Japanese banks are still saddled with unrecoverable debts estimated to be worth ¥35 trillion. Despite the government launching 13 major spending packages worth a total of ¥135 trillion (Clairmont, 2001; McCormack, 2001: xiii), there has been no sign of an economic revival.

Compensating for the retraction of corporate investments, the rise in Japanese government expenditures had turned a budget surplus of 2 percent of GDP into a deficit of 7 percent of GDP by 2001 (Redding, 2002). Any attempt to restructure the economy by trimming government expenditure would inevitably lead to an explosive growth of unemployment which, at 5.6 percent, is already at a post-Second World War high. In these conditions, if the government were to cut its outlays on construction, which constituted some 43 percent of the national budget in 1993 and employed some 10 percent of the workforce (McCormack, 2001: 33), the social dislocations would be all the more catastrophic.

Finally, unlike the ‘hollowing out’ of Japanese industries in the 1980s when the high value of the yen led to a spurt in Japanese investments in Southeast Asia, since the onset of the current economic crisis employment cutbacks and factory closures in Southeast Asia have paralleled those in Japan, as major corporations have redirected their investment flows to China where production costs are significantly lower. Since 1990, China has accounted for 45 percent of the $719 billion in foreign direct investment flowing to Asia. While Great Britain overtook Japan as the largest investor in Southeast Asia in 1998, Japanese investments to China more than doubled in the 1990s and its trade with China (including Hong Kong) in 2000 was three times its level the previous year. Thus, even as compression of export prices following the depreciation of the yen led to the re-emergence of high trade surpluses with the United States in 1998, its surplus with Asia fell by 36 percent (Abrahams, 1999; Arnold, 1999a; Arnold, 2001; Brooke, 2001b; Chandler, 2001a; Gilpin, 2000: 169–79; McDonald, 2001).

If the cannibalization of the chaebol and the weakening of keiretsu ties in Japan eroded the position of small parts suppliers all along the Pacific coasts of Asia, in certain technologically-sophisticated sectors, some three decades of sustained economic growth and affiliative ties as OEM suppliers for major enterprises had created strong research-based small enterprises like laptop computer parts in Taiwan and audiocard and multimedia components in Singapore. In these cases, tie-ups with major manufacturers had helped to compensate for small domestic markets (Wong Poh-Kam et al., 1997). Agglomeration economies enabled Taiwan's Quanta Computer to emerge as the world's largest maker of notebook computers, overtaking Toshiba in 2001, producing computers for seven of the top ten notebook companies. With the development of a large supplier base – with companies such as Compal, Asutek, Arima, and Taiwan Semiconductor – Quanta can assemble laptops in 48 hours from receiving orders and has now also diversified into desktops by putting together Apple's sleek new iMac system (Landler, 2002).

Taiwan's smaller and more decentralized industrial sector also implied that its industries were not burdened with the high debt–equity ratios of the chaebol. While the push toward industrial upgrading had led to a steady rise in royalty payments for South Korean enterprises – between 1962 and 1996, the government estimated these amounted to $13.2 billion, while total Taiwanese imports of technology amounted to a mere $500 million by 1993 (Noble and Ravenhill, 2000: 85–6). Unlike South Korea and the other hemorrhaging economies in the region, Taiwan was a net exporter of capital and was hence less vulnerable to the rapid withdrawal of capital. The dominance of state- and GMD-controlled companies also meant that the Taiwanese government could formulate a more coordinated strategy toward overseas expansion of its production networks. However, increasing competitive pressures in the form of falling exchange values in the region contributed to a relentless outflow of manufacturing investments especially to China – in 2000, China received some $26 billion of Taiwan's total overseas investment of $76 billion (Cheng, 2001) – and to a corresponding fall of Taiwan's GDP as its unemployment rates reached record highs. Even in computers, Taiwanese manufacturers are shifting production to China and by the end of 2003, it is estimated that over two-thirds of notebook computers made by Taiwanese companies will be assembled in China (Landler, 2002).

The dominance of government-controlled companies in its economy also insulated Singapore from the growing trans-border expansion of production and procurement networks. Whereas the transnational expansion of corporations based in Japan or South Korea undermined the coherence of national economy-making, the Singapore government saw the overseas expansion of its companies – such as DBS Bank's purchase of Hong Kong's Dao Heng Bank in April 2001, or SingTel's acquisition of Australia's Cable and Wireless Optus – as extending the island-state's ‘global reach’ (Wee, 2001: 997).

Singapore was also fortunate that Seagate Technologies chose it as the site for its disk drive manufacturing operations in the early 1980s. The swift development of a number of related industries and the creation of a pool of skills in subassembly operations associated with precision engineering which was industry-specific but not firm-specific meant that the island-state soon accounted for some 40–50 percent of the global production of disk drives. Despite the transfer of some lower value-added subassembly operations to neighboring lower-wage sites, as components for hard disk drives have very stringent precision and quality requirements, firms that had developed the capacity to supply these components also had the capacity to provision other electronics assemblers as well (Wong Poh-Kam, 2001). Nevertheless, Singapore's small population base and compact size suggests that this model has extremely limited relevance for other states.

Moreover, as theorists of ‘late development’ have argued, a central strategy of successful rapid industrialization has been the protection of infant industries and the disproportionate allocation of resources to flagship industrial sectors such as steel and other heavy industries. In such allocations, the profitability or comparative advantage of strategic industries was less important than product quality and technological prowess. It is by no means certain that the same policies are possible in technologies based not on mass production but on innovation and knowledge-intensity – software and the Internet, for instance. If a ‘shop-floor’ focus enabled Japanese and South Korean corporations to reverse-engineer automobiles and consumer electronic products and devise cheaper ways to manufacture them, such techniques are less significant when the rapid pace of innovations in information technologies create new products in approximately 18 months or less! The South Korean EPB's refusal to see the potential of semiconductors in the late 1980s dramatically silhouetted the inadequacies of administrative guidance when the economic environment had been radically transformed by new technologies (Yeon-ho Lee and Hyuk-Rae Kim, 2000: 122). Similarly, though Japanese manufacturing industries continued to be at the leading edge, they have been reduced to the status of price-takers in computer and semiconductor industries, and the competitive pace in finance, insurance, and software in Japan is increasingly set by foreign firms such as Citicorp, GE Capital, and Microsoft (Pempel, 1998: 140–1; Murphy, 2000: 35).

Notwithstanding these concerns, after its restoration to Chinese sovereignty, the Tung Chee-hwa Administration has adopted a policy to transform Hong Kong into a high-technology hub to compensate for the inexorable drain of manufacturing jobs from the Special Administrative Region (SAR). Envisaging Hong Kong to become a center for food and pharmaceuticals based on Chinese medicine, as well as a leading supplier of high value-added components and a regional center for information and entertainment based on multimedia formats, the SAR government in 1999 unveiled plans to create a US$1.7 billion technology park or Cyberport to create a strategic cluster of information technology industries. Nevertheless, whether Hong Kong has, or can attract, a sufficient pool of people with the necessary skills remains to seen (So and Chan, 2002; So, 2002; So, n.d.).

In short, though the sharp currency depreciations experienced by several East and Southeast Asian economies appear to have been arrested, the hollowing out of their industrial bases has led to widespread unemployment, bankruptcies, and distress sales of otherwise viable enterprises. Relaxation of ceilings and restrictions on foreign investments in the context of plunging currency values have seen the sale of corporate crown jewels to overseas investors at fire-sale prices. By shifting the relative balance of power between governments and enterprises in favor of the former, the crisis has endowed bureaucratic state apparatuses with a greater degree of autonomy, especially since a wave of foreclosures and layoffs also weakened the power of organized labor. In this changed ecology of production, trade, and investment, the greater prominence of governments is manifested in the emergence of a new institutional armature for regional integration along Asia's Pacific shores as outlined in the Epilogue. But before turning to that, we need to survey how the depreciating currency values and a decline in effective demand in the erstwhile ‘dragons’ has exacerbated the problem of overproduction just as workers in Western Europe and North America face increasing pressure from low-cost imports from the Asian economies.

Houses of glass

Though the United States and Western Europe appeared to have weathered the storm, as the economic crisis ricocheted from the Asian rimlands to cause capital flights from Russia and Latin America in 1998, compression of export prices from economies in East and Southeast Asia soon devastated the manufacturing sector in the United States. As we shall see below, the end of the Cold War had parallel and contradictory effects on the United States and Western Europe. While a decline in military expenditures following the end of the Cold War and corporate tax cuts had stimulated fresh investments in manufacturing in the United States, the reverse Plaza Accord of 1995 once again shifted competitive pressures onto US manufacturers. However, rising equity prices meant that overseas investors continued to pump money into US stocks and the stock market boom helped turn the federal deficit into a small surplus by 1998. Perhaps more impressively, soaring stock prices sent technology stocks sky-high and irresistibly drew ever-increasing capital flows to the United States. At the same time, the attendant asset-price inflation led to widening income inequalities in the United States as well as a parallel expansion of consumer expenditures. When manufacturers, buoyed by higher levels of expenditure and the ease of raising money, undertook a new bout of investments, it exacerbated the problem of overproduction precisely when demand contracted in the Asian rimlands and exports from the region undercut prices. Low rates of capacity utilization, in turn, drove profits downwards and pulled stock prices sharply lower. Conversely, the fall of the Berlin Wall had saddled Germany with the huge cost of political reunification with the erstwhile German Democratic Republic and threatened to undermine moves toward a common European currency. The high interest rates necessary to preserve the latter project resulted in high levels of unemployment and the stringent conditions negotiated for the common currency constrained macroeconomic options for governments. If the rise of the dollar provided a respite, the break was fleeting since the compression of export prices from the Asian rimlands constrained an expansion of manufacturing.

In the first place, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the reunification of Germany had yielded a significant ‘peace dividend’ for the United States as the numbers of its troops garrisoned in Western Europe were slashed from some 300,000 in 1989 to about 122,000 in 1997–98. Defense expenditures fell correspondingly by 30 percent in real terms during the same period (Calleo, 1998). The extent of this fall in defense spending is partly exaggerated by the extraordinary rise in military expenditure during Ronald Reagan's presidency and defense spending in 1997 well exceeded spending levels during most of the Cold War years before 1980 (Achcar, 2000: 103). Nevertheless, the decline was significant enough that, along with a long-term fall in interest rates,6 it permitted the Clinton administration to reduce the annual fiscal deficit from 4.6 percent of GDP in 1993 when it came into office to 1.2 percent of GDP by January 1998 (Calleo and Rowland, 1973; Brenner, 2002).

Combined with the prior corporate tax cuts initiated by the Reagan Administration – by the early 1990s, corporate taxation was at 23 percent of pre-tax profits compared with 52 percent between 1960 and 1964 (Brenner, 2002: 70) – the fall in real wages during the 1970s and 1980s and a low dollar stimulated a fresh wave of manufacturing investments in the United States. From languishing at an annual average rate of just 1.3 percent between 1982 and 1990, manufacturing investment rose steeply to an average annual rate of 9.5 percent between 1993 and 1997 and to 10.5 percent by 1999. In the context of the decommissioning of obsolete plant and equipment in the 1980s, and the accompanying shrinkage of the manufacturing labor force, this spurt of new investments and the reorganization of production processes also led to an annual average increase of 4.4 percent in labor productivity between 1993 and 1997 (Brenner, 2002: 76–7).

However, though US manufacturers were able to hold wages down, the rise in labor productivity did not compensate for an average annual rate of 6 percent rise in the value of the dollar following the reverse Plaza Accord of 1995. Consequently, as export prices declined by an average of 2.6 percent in both 1996 and 1997 to flatten profit rates in the manufacturing sector, there was increased speculation in equities. Simultaneously, to maintain a high dollar, the Japanese government as well as investors from all over the world poured money into US government securities – the purchase of US government securities in 1995 being more than double the average of the previous four years. Between 1995 and 1997, investors from overseas bought $700 billion in US government securities – a figure that exceeded not only the total new debt issued by the US Treasury during this period but also $266.2 billion of US government debt previously held by US residents. This torrent of cash inflows pushed down interest rates on 30-year Treasury bonds and led to a stratospheric growth in stock prices: the New York Stock Exchange index rising by 80 percent between 1994 and 1997 while the Standard and Poor index more than doubled. Indeed, by the spring of 1997, the value of US stocks was greater than the value of the US GDP of about $8 trillion. After peaking at 180 percent of the US GDP in 2000, it fell back to 150 percent by early 2000 (Brenner, 2002: 135–48; Gowan, 1999: 119; Therborn, 2001: 97).

This extraordinary rise of equity prices was driven in particular by corporations taking advantage of low interest rates to borrow money to buy back their own stocks so as to raise their value even further. Since corporate executives and even employees increasingly received compensation in stock options, bidding up stock prices was to their advantage while selling stock and using the proceeds to finance investments would work against them by lowering the value of their stock holdings. Thus, whereas the highest annual total for stock purchases before the mid-1990s had been the $51.4 billion recorded in 1989, the value of stock repurchases was $134.3 billion in 1997, $169.1 billion in 1998, and $145.5 billion in 1999 (Brenner, 2002: 148).

For purposes of the present discussion, this mercurial growth in equity prices had six major consequences. In the first instance, the rise in capital gains tax receipts as a result of skyrocketing equity prices from $44 billion in 1995 to $100 billion in 1998 directly contributed to the transformation of the US federal deficit into a small surplus in fiscal 1998 (Gowan, 1999: 120; Pollin, 2000: 24; Phillips, 2002: 103). Second, firms could meet their pension fund obligations by rising portfolio values rather than by channeling funds into retirement accounts and hence release cash for distribution as dividends (Pollin, 2000: 40). Third, rising equity prices were crucial for start-up firms, especially in the technology sector, and they were, albeit briefly, the brightest stars in an asset-inflated firmament. From an annual average of $3 billion for initial public offerings (IPOs) between 1980 and 1994, the annual gross proceeds from IPOs reached stratospheric heights: $30 billion between 1994 and 1998, $60 billion per annum in 1999 and 2000 (Brenner, 2002: 195). The results of this extraordinary infusion of funds into new start-up technology stocks was spectacular:

The Internet stocks that have headlined the mania over the last year [1998] are without known precedent in US financial history. At its highs in early April, the market capitalization of Priceline.com, which sells airline tickets on the web and has microscopic revenues, was twice that of United Airlines and just a hair under American's. America Online was worth nearly as much as Disney and Time Warner combined, and more than GM and Ford combined. Yahoo was capitalized a third higher than Boeing, and eBay nearly as much as CBS. At its peak, AOL sported a price/earnings ratio of 720, Yahoo! of 1,468 and eBay of 9,751 … previous world-transformative events had never been capitalized like this … RCA peaked at a P/E of 73 in 1929. Xerox traded at a P/E of 123 in 1961, Apple maxed out at a P/E of 150 in 1980. And all these companies were pretty quick to turn a profit, and once they did, their growth rates were ripping. In the so-called Nifty Fifty era of the early 1970s, the half-hundred glamour stocks that led the market sported P/Es of forty to sixty… . And those evaluations were once legendary for their extravagance.

(Doug Henwood, quoted in Pollin, 2000: 41)

This ‘irrational exuberance’ of the stock market, as Greenspan once characterized it, magnetically attracted foreign investments, especially after the meltdown in East Asia – and the ensuing flights of capital from Latin America and Russia in 1998 (Wade and Veneroso, 1998b: 15–18; The Economist, 1999). From accounting for just 4 percent of the total net purchases of US corporate equities in 1995, private investors from overseas accounted for 25.5 percent by 1999 and for 52 percent by the first half of 2000, while their share of total corporate bond purchases rose from 17 percent to 44 percent during the same period. By the first half of 2000, holdings of gross US assets by overseas investors amounted to $6.7 trillion or 78 percent of US GDP and since these assets could be liquidated relatively easily, the US economy was more vulnerable to capital flows than ever before (Brenner, 2002: 208–9).

The fourth consequence of the growth in equity prices was that the market capitalization of shares held by households increased from $4 trillion to $12.2 trillion between 1994 and the first quarter of 2000. This stimulated an unprecedented wave of consumer borrowing, and by 2000 household outstanding debt (including mortgages and consumer debt) as a percentage of personal disposable income had attained a hitherto-unimaginable level of 97 percent. Corporate debt rose in tandem, quadrupling between 1994 and the first half of 2000. Conversely, the personal savings rate which had averaged around 10.9 percent between 1950 and 1992 plunged from 8.7 percent in 1992 to _0.12 percent in 1990 (Brenner, 2002: 189–92; Pollin, 2000: 32–3). With debts growing faster than assets, the Federal Reserve Bank's triennial survey of consumer finances indicated that the median US household's net worth (including home equity) declined from $51,640 to $49,900 between 1989 and 1995 (Phillips, 2002: 107).

From this perspective it can be seen that US opposition to any attempt to rollback financial liberalization in the crisis-hit Asian economies rose from the need to draw on savings in other economies to compensate for its very low domestic savings rates, and to maintain its high rates of consumption and investment (Wade and Veneroso, 1998b: 35–8; Wade, 1998a: 1540). The greater the degree of world financial integration, the greater the ability of Wall Street firms to use the American dollar's role as the international reserve currency to their advantage. Since US Treasury bills offer a means to borrow money cheaply from world markets, the intermediated funds can be recycled as FDI outflows, portfolio investments, and loans at much higher rates of interest. Thus, support for the IMF packages that used bail out funds to sustain exchange-rates at unsustainable levels allowed the rich to convert their money into dollars and whisk it away to safe havens in the United States rather than to stem the currency hemorrhage as it was intended to do (Stiglitz, 2002: 95–6).

Fifth, a corollary to the asset price inflation and the parallel plunge in the US domestic rates of savings was a widening in inequalities in income and wealth. In 1999, an article in the New York Times put it starkly: ‘The gap between the rich and the poor has grown into an economic chasm so wide that this year the richest 2.7 million Americans, the top 1 percent, will have as many after-tax dollars to spend as the bottom 100 million’ (quoted in Phillips, 2002: 103; Brenner, 2002: 191). Most notably, inequalities in income and wealth widened not merely because the rich were getting richer at a faster rate: it was also because the poor were becoming poorer! Though the federal minimum wage was hiked from $4.25 an hour to $5.15 in 1996, the real value of the new minimum wage was 30 percent less than its real value in 1968 (Pollin, 2000: 21; Brenner, 2002: 220). The average real after-tax income of the middle 60 percent of the population was lower in 1999 than it had been in 1977. To maintain their household incomes, increasing numbers of women were thrust into the job market: in the workforce, the percentage of women with children under six rose from 19 percent in 1960 to 64 percent in 1995, a figure higher than in any other OECD member-state. Between 1989 and 1999, the average work year increased by 184 hours and the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicated that a typical worker in the US worked the equivalent of nine work weeks more than the typical worker in Western Europe (Phillips, 2002: 111–13). From this perspective, the low unemployment rate of only 4.3 percent in 1996 was due more to low wages making it necessary for people to work more rather than to its inherent dynamism. Indeed, Bruce Western and Katherine Beckett (1999) have argued that if the effects of the high rates of incarceration in the United States are included – being 5 to 10 times larger than the OECD average in 1993 – the rate of unemployment in the mid-1990s would be around 8 percent, and even worse if the long-term effects of incarceration are factored in.

Finally, by inflating the value of household assets, soaring equity prices triggered a parallel expansion in consumer expenditures: from an average annual rate of 12 percent between 1992 and 1997, consumer expenditures on durable manufactured goods surged to an average annual pace of 12 percent between 1997 and the first half of 2000. High consumer demand and easy access to capital, due to the powerful attraction posed by equity prices in the US, led to a sustained growth in manufacturing investments – by an annual average of 12 percent between 1991 and the first half of 2000, with investments disproportionately concentrated in information technology (Brenner, 2002: 202, 205–34).

However, the rise of the dollar since 1995, and especially after East and Southeast Asian currencies plunged in value since 1997, provided a devastating blow to manufacturing profits in the United States. Increased capacity, as we have already seen in the previous chapter, had been exerting a steady downward pressure on profits. In dollar terms, manufacturing prices in the world market fell by an annual average rate of 4 percent between 1995 and 2000 as a result both of rampant overproduction and of East and Southeast Asian producers selling at distress prices. The temporal coincidence of the rise of consumer expenditures in the US and the appreciation of the dollar also facilitated a rapid expansion of imports – and the US manufacturing trade deficit increased by two and a half times between the onset of the crisis in the Asian rimlands in 1997 and 2000. Correspondingly, the US corporate manufacturing rate fell by 20 percent during this three-year period (Brenner, 2002: 204–5, 209, 214–15, 237).

Conversely, steep devaluations of the currencies of Japan and of the East and Southeast Asian NICs have led them to register record surpluses in their trade with the United States, Western Europe, and Latin America. In 1998, Japan's politically contentious trade surplus with the United States grew by 23 percent over the previous year: at ¥6,700 billion, it was the highest since 1987. As a result of the IMF-mandated structural reforms and the ensuing cutbacks in imports, South Korea's foreign exchange reserves stood at an all-time high of $41 billion by August 1998 and were estimated to reach $50 billion by the end of the year (Wade and Veneroso, 1998b: 25; Cumings, 1998: 70; Abrahams, 1999).

Yet, propelled by steady infusions of capital by overseas investors, equity prices continued to rise in 1999 and 2000 – inflows of non-residential investments rose by 11 percent in 1999 and by an annualized rate of 14 percent in the first half of 2000 – as the NASDAQ index of high-technology stocks more than doubled. Driven by returns on venture capital which reached 165 percent in 1999, net purchases of US stocks by overseas investors reached a new high of $172.9 billion the following year. While the scale and velocity of such asset-price inflation stimulated further investments, it exacerbated the problem of over production and Walden Bello and Robert Brenner note that by April 2001, the utilization capacity of telecommunications networks languished at a mere 2.5 percent, leading to massive declines in stock prices of industry giants like AT&T, Sprint, and Worldcom. These declines ricocheted onto makers of telecommunications equipment – switching routers, fiber-optic cables, etc. – while computer makers announced substantial layoffs. Non-technology sectors had of course been plagued by overcapacity for much longer – according to Federal Reserve estimates, manufacturing plants in the US were operating at only 73 percent of capacity in December 2001. Even when factories are operating at full capacity, appearances may be deceptive. Contracts between the United Auto Workers and the US automobile companies – valid until September 2003 – require the automakers to pay their employees their full salary whether they are working or not. Hence, it was more economical for GM, Ford, and Chrysler to produce and sell cars at a small loss rather than to shut plants down completely. When the contract expires however, current estimates suggest that some 15,000 workers would be laid off – and as each job lost at a final assembly plant could lead to the loss of four jobs for part suppliers, the effects would be magnified. By early 2001, the economic slowdown began to deflate the stock market bubble and the value of household-owned equities fell by 31 percent between the first quarter of 2000 and the first quarter of 2001. This steep decline was almost immediately telegraphed by a significant dampening of consumer expenditures on durable goods which further depressed stock prices in a vicious cycle (Bello, 2001; Brenner, 2002: 225–6, 244–5, 249, 251–2, 256–9; Pearlstein, 2002).

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, though the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the withdrawal of the Red Army had rendered Germany less susceptible to US pressure, the cost of reunification meant that Germany enjoyed no ‘peace dividend.’ Instead, Chancellor Helmut Kohl's decision to override Bundesbank recommendations and permit the conversion of ost-marks on a one-to-one basis to deutsche marks not only led to higher budgetary deficits but also put increasing pressure on weaker currencies in the European Monetary System (EMS). Since raising taxes was politically unfeasible, German monetary authorities had raised interest rates to finance the deficit. This was not accompanied by a revaluation of the deutsche mark because it would have come up against the determination of the French government to maintain a strong franc, and undermined French support for a common European currency. Abnormally high interest rates in France and Germany forced Britain, Italy and Portugal to abandon the EMS altogether in 1992. High interest rates in France also lifted unemployment levels above 10 percent, and ballooning unemployment benefits led to high fiscal deficits. At the same time, the depreciation of the dollar against the deutsche mark exerted pressures on all European currencies. If the slide of the pound and the lira after Britain and Italy left the EMS enabled these economies to experience an export boom and enjoy relatively low unemployment rates, it jeopardized monetary union across the continent. Relatively high costs undermined the competitiveness of the German economy – the annual average GDP growth rate being a mere 0.9 percent between 1991 and 1995 – and the slower growth of the German economy exerted a downward pressure on other European economies. The rate of unemployment in the eleven European Union countries averaged 11.3 percent in 1996 when the average annual rate of unemployment in the 16 leading economies during the Great Depression between 1930 and 1938 had only been 10.3 percent. Moreover, as the dollar began to rise after 1995, while the deutsche mark and the franc lost between 20 and 23 percent of their value, competitive pressures were shifted onto Britain where the pound, outside the EMS, tended to shadow the dollar. However, stringent conditions for the common European currency negotiated under the Maastricht Treaty limited macroeconomic options for other European states. Finally, compression of export prices in East and Southeast Asia limited the growth of manufactures in Western Europe even after the rise of the US dollar. For instance, the Japanese trade surplus with the European Union grew by 26 percent in 1998 (Brenner, 1998: 3; Brenner, 2002: 124–6; Strange, 1998: 70–1, 81, 152; Abrahams, 1999; Calleo, 2001: 189–95).

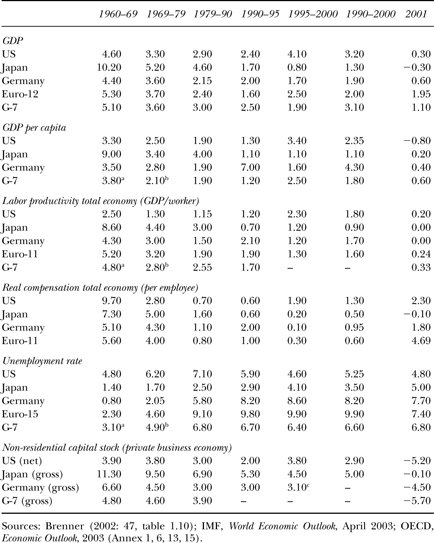

In the first half of the 1990s, then, as indicated by Table 6.2, the three major blocs of core states – Japan, the United States, and Western Europe – experienced their lowest rates of growth in half a century. Though GDP growth in the US picked up marginally in the latter half of the decade, there was no parallel recovery in Japan and Western Europe and, on the whole, persistent overproduction dampened possibilities of a smooth recovery: none of the major capitalist engines was capable of pulling the world economy from the rut (Pollin, 2000: 28–31; Brenner, 2002: 46–7).

To recapitulate, the meltdown of several East and Southeast Asian economies in 1997–98 was so unexpected that as their governing elites groped for lifelines, Western governments used the emergency cash infusions from the IMF as a battering ram to restructure the ailing economies. The standard IMF prescription of raising interest rates to stabilize currencies wreaked havoc on companies which depended on short-term loans even for routine operating costs. Contrary to the usual practice of restricting foreign access to a country's assets when its credit has dried up, the IMF even pressured governments accepting its emergency loans and loan guarantees to accepting greater foreign ownership of assets. And the insistence on maintaining open capital markets facilitated capital flight as investors rushed to pull their capital out of the ailing economies before the situation deteriorated even further.