3 The making of industrial behemoths

Patterns of state intervention and industrial organization

Presciently anticipating theorists of the ‘developmental state,’ Friedrich List had argued in 1885 that in ‘less advanced nations … a perfectly developed manufacturing industry, an important mercantile marine, and foreign trade on a really large scale, can only be attained by means of the interposition of the power of the State’ (quoted in Leftwich, 1995: 401). Similarly, Alexander Gerschenkron (1962) concluded from a study of pat-terns of ‘late industrialization’ that state intervention in ‘relatively backward’ countries was especially important because the average size of plants needed to be larger precisely when capital was scare. Building on his analysis, Ellen Kay Trimberger's (1978: 4) comparative study of Egypt, Japan, Peru, and Turkey indicated that states were able to be effective in economic development when the

bureaucratic state apparatus achieved relative autonomy when, first, those holding high civil and military office were not drawn from dominant landed, commercial, or industrial classes; and, second, where they did not immediately form close relations with these classes after achieving power.

While a recognition of the significance of the relative autonomy of the state and the vital importance of government intervention in the economy for late-industrializers thus has a long and distinguished pedigree, the onset of the irreversible decline of centrally-planned economies since the late 1970s led to a neoclassical resurgence. It was argued that state intervention had ‘generated inefficient industries requiring permanent subsidization for their survival’ and that it also tended to foster ‘rent-seeking’ and thereby detracted ‘the attention of economic agents from productive activities into lobbying for increased allocations of government subsidies and protection’ (Onis, 1991: 109). The clearest empirical refutation against this revival of neoclassical orthodoxy emerged from the Asian rim-lands.

By the early 1980s, the sustained rates of economic growth registered by these states led to a reassessment of the role of dirigisme in economic development. Characterizing Japan as a ‘developmental state,’ Chalmers Johnson (1982: 18–20) distinguished it from both the ‘market rational’ orientation of other core economies and the ‘plan ideological’ orientation of centrally-planned economies. Unlike ‘market rational’ states like the United States which were concerned with the rules and procedures of economic competition rather than with the type of industries that were needed, the ‘plan rational’ orientation of the Japanese government emphasized substantive economic issues. Conversely, unlike the centrally-planned economies, that he charged were primarily concerned with the state ownership of the means of production rather than developmental goals, the Japanese state emphasized economic development as its preeminent goal. Key elements of a ‘developmental state’ included an elite economic bureaucracy insulated from routine political pressures and endowed with the autonomy to pursue development goals and the ‘perfection of market conforming methods of state intervention in the economy’ (Johnson, 1982: 317). These methods centered on specifying a set of goals and comparing the performance of firms with a set of external reference economies. Expanding the application of the concept of ‘developmental state’ to South Korea and Taiwan, Alice Amsden (1989) and Robert Wade (1990) explored the complexities of strategic industrial policies. Similarly, several authors have underlined the critical importance of state intervention in the emergence of Hong Kong and Singapore as off-shore manufacturing platforms (Castells et al., 1990; Appelbaum and Henderson, 1992; Bello and Rosenfeld, 1990; Schiffer, 1991; Rodan, 1989; Henderson, 1993).

If these accounts successfully dethroned the neoclassical orthodoxy, their tendency to view the state apparatus as a narrowly defined decision-making body ‘rather than as a set of complex and highly contested social relations’ (Choi, 1998: 51) tended to reify the state. Moreover, their exclusive focus on the administrative apparatus precluded a recognition of the wider political context of industrial planning and, at least implicitly, suggested that the installation of similar technocratic methods of industrial guidance will lead to a replication of East and Southeast Asian trajectories of growth in other low- and middle-income states (Friedman, 1988: 5, 30).

Additionally, though advocates of the developmental state were clear in distinguishing the relatively autonomous state structures along the Asian rimlands from other ‘newly-industrializing countries,’ once developmental state apparatuses had been installed, they tended to view these as perpetual growth machines. In particular, there was no recognition that rapid economic growth could tilt the balance of power from elite bureaucratic agencies toward other social actors as working classes became more class conscious and as corporations outgrew the need for subsidies and protection. Most notably, as Ziya Onis (1991: 122) forewarned, the ‘inability of the state elites to discipline private business in exchange for subsidies may lead to a situation where selective subsidies can easily degenerate into a major instrument of rent seeking by individual groups.’

Despite these reservations, there is widespread acknowledgment of the fundamental importance of state intervention. Strategies of intervention and the institutional structures of capital accumulation in each of these jurisdictions were, however, shaped by different configurations of relations between state bureaucracies, social classes, and multinational capital within the wider political and trading arrangements of US hegemony. The scope of dirigisme was also determined by their different endowments of land and natural resources, the maturity and technical sophistication of their domestic bourgeoisies, the competence and technical expertise of their pilot economic agencies, and the size of their domestic markets. The three US client states were able to embark on a strategy of state-led industrialization with large infusions of aid from the hegemonic power and American military procurements from Japan. Hong Kong and Singapore had neither the land, natural resource endowments nor domestic markets comparable to South Korea or Taiwan, not to speak of Japan, to embark on an ISI strategy. As British colonies, the two city-states were also not recipients of large doses of American aid. At the same time, while political conditions led to the creation of a vast state sector in Taiwan which was supported by a large number of small- and medium-scale enterprises, the Rhee administration sought to create a domestic constituency of support by fostering the emergence of a class of big capitalists. If the creation of gigantic industrial conglomerates in South Korea bore some resemblance to the revival of monopoly capital in Japan, organizational immaturity and technical inexperience characterized the former. Once again, the two city-states faced different constraints. The transformation of Hong Kong from an entrepôt to an industrial and financial center occurred under the auspices of a colonial administration that acted in many ways as the executive committee of large business interests. The small size of domestic capital in Singapore compelled the Lee administration to create favorable conditions to attract foreign investments, and auspiciously for the host government the timing could not have been better as an increase in competitive pressures in the core disposed TNCs to relocate the lower end of their manufacturing operations to off-shore locations to cut labor costs precisely when Singapore was expelled from the Malaysian Federation.

The combination of these divergences imply that though the reconstitution of postwar regimes in the US client states and in the two city-states strung along Asia's Pacific coasts were marked by the propensity of their administrations to intervene in economic affairs to a degree unparalleled outside the centrally-planned economies, the patterns of state intervention and institutional structures of capital accumulation were strikingly different in each jurisdiction. Consequently, rather than trace similarities in these patterns, this chapter will chart the confluence of the varied trajectories of class forces, external influences, political exigencies, and internal constraints on their respective patterns of state intervention and dominant forms of industrial organization.

In the context of the geopolitical ecology of the post-Second World War reconstitution of the world market under US tutelage, the timing of the adoption of an industrialization drive in each jurisdiction also had important consequences. While the Korean War provided a spur for the reconstruction of the Japanese economy, it led to the initiation of a strategy for economic development in Taiwan and reoriented developmental strategies in Hong Kong. If the war finally led to agrarian change in South Korea and laid the political conditions for its future development, the material and human devastation caused by the hostilities had consequential consequences for class formation. What the Korean War did for the rehabilitation of the Japanese economy, the Vietnam War did for the economies of Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. Singapore, which gained independence more than a decade after the decolonization of Korea and Taiwan, confronted an entirely different set of problems and constraints – narrow domestic markets, low natural resource endowments, and a small national bourgeoisie. Daunting as these conditions were, deepening US involvement in Vietnam boosted demand for petrochemicals and other supplies from Singapore while Taiwan and South Korea became suppliers of a variety of labor-intensive products for the US military. The coincidence of increasing welfare benefits in the 1960s with the sharp rise in military expenditures occasioned by the war in Vietnam led to a pressing need for the US government to economize in the procurement of supplies – and it was cheaper to obtain supplies of requisite quality from Japan and the future ‘dragons’ than from within the United States or elsewhere (Arrighi, 1994: 341). Successive US administrations therefore tolerated the closure of markets along the Asian rimlands to American products while allowing enterprises in these economies relatively free access to US markets – a privilege not accorded to American allies elsewhere.

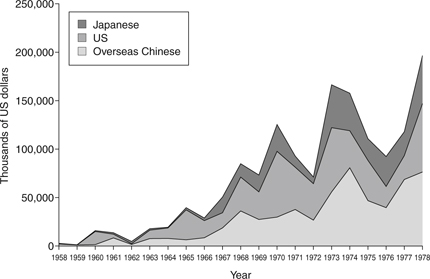

Most importantly, the different patterns of state intervention and industrial organization conditioned the emergence of networks of regional integration charted in subsequent chapters and were themselves reshaped in turn. The singular characteristic of the outward expansion of Japanese capital in the 1960s – being spearheaded by small- and medium-scale enterprises – was possible only due to the hierarchical structure of subcontracting networks and the organizational armature of the general trading companies. If the widespread filigree of small- and medium-scale enterprises in Taiwan could readily accommodate this transfer of less-skilled manufacturing processes from Japan, the large South Korean chaebol could more easily accommodate the transfer of heavy and chemical industries in the 1970s. At the same time, the practice of channeling huge loans to the chaebol, necessary to finance large undertakings, created a culture of high debt-equity ratios, the adverse consequences of which were brutally exposed during the economic meltdown of 1997–98. Discrimination by nationalized banks against native islanders in Taiwan fostered no similar culture of debt-financed industrialization. The greater weight of state-owned enterprises in Taiwan and Singapore, as we shall see in Chapter 6, enabled their governments to deploy macroeconomic controls more effectively even when the transborder expansion of corporate networks had rendered national industrial policies increasingly anachronistic in Japan and South Korea.

Politics in command?

If Albert Hirschman (1958: 5) was right in arguing that economic development ‘depends not so much on finding optimal combinations for given resources and factors of production as on calling forth and enlisting for development purposes resources and abilities that are hidden, scattered, or badly utilised,’ then in low- and middle-income countries, the state was best placed to formulate long-term developmental plans. Private investors in these economies, as advocates of Big Push developmental strategies had argued, were hesitant to make new investments because they were unsure whether other complementary investments necessary to sustain their investments would occur. Japan and the Four Dragons were especially well-placed to coordinate national industrial plans because they were relatively free from populist pressures.

This was most clearly evident in the case of South Korea, where rapid economic growth was initiated only after General Park's coup d’ état of 1961. If Singapore was spared a military coup, repressive measures implemented by the Lee Kuan Yew administration virtually emasculated political opposition to the PAP – not a single opposition candidate won an election to parliament between 1965 and 1981. Authoritarianism in Taiwan lasted until the lifting of martial law in 1987 while elections based on adult franchise were instituted in Hong Kong only in 1991, a few years before the British transfer of sovereignty to China (see So and May, 1993). Even in Japan, where democratic norms were observed, the iron grip of the LDP was loosened only in 1993, and for almost 40 years it was effectively a one-party state. Differences in power structures and in their relationships to state bureaucracies and social classes were important determinants of the patterns of state intervention and institutional structures of capital accumulation adopted in each jurisdiction.

In all three US client states, though land reform was a key element in the subordination of agriculture to a state-directed industrialization drive, the dynamics of agrarian change were conditioned by the relative potency of rural insurrection and by the specific institutional patterns of state power in each jurisdiction. Similar considerations also determined the corralling of labor movements in these states as well as in Hong Kong and Singapore. Finally, though domestic bourgeoisies in all five future ‘miracle’ economies were dependent on the state apparatus, the degrees of dependence varied considerably. If industrialists in Japan and Hong Kong were ‘mature’ and able to work in partnership with state bureaucrats and had a significant input into policy formation, the budding industrialists in South Korea and Taiwan were considerably more subordinate to political authority and the small commercial bourgeoisie in Singapore so insignificant that they were bypassed by the state altogether.

Japan

Spared from the ‘winnowing hand’ of the Supreme Commander Allied Powers (SCAP), the civil service had a virtual monopoly on governmental expertise, representing as they did almost all of Japan's remaining ‘political grownups’ (Pempel, 1998: 85). Indeed, far from being decimated, in the first three years of the Occupation, the civil service had grown by 84 percent over its highest wartime strength (Johnson, 1982: 44). A widespread consensus among the elite that the bureaucracy was vital to postwar recovery was encapsulated in a lead editorial in Ch ü ö k öron in August 1947:

under the present circumstances of defeat, it is impossible to return to a laissez-faire economy, and … every aspect of economic life necessarily requires an expansion of planning and control, the functions and significance of the bureaucracy are expanding with each passing day. It is not possible to imagine the dissolution of the bureaucracy in the same sense as the dissolution of the military or the zaibatsu, since the bureaucracy as a concentration of technical expertise must grow as the administrative sector broadens and becomes more complex.

(quoted in Johnson, 1982: 44)

This consensus reflected the close cooperation between the bureaucracy and the Keidanren.

The three main instruments for state intervention included control over foreign exchange and the ability to strategically target industries for development; provision of loans at preferential rates of interest, and tax concessions to lower production costs in chosen sectors; and the power to order the creation of industrial cartels and bank-based industrial groups (Johnson, 1982: 199). Control over foreign exchange, initially vested in the Foreign Exchange Control Board – and transferred in 1952 after the peace treaty, to MITI – lasted until the liberalization of trade in 1964. The establishment of a Foreign Investment Committee with oversight over all contracts involving foreign investments, acquisition of licenses and patents, conferred enormous statutory power on the ministry to regulate the import of foreign technology that lasted until the laws were rescindedin November 1979, almost thirty years after the law was approved as a temporary measure by the US occupation authorities (Johnson, 1982: 194, 217, 302; Morris-Suzuki, 1994: 168).

The imperative to ensure that adequate investment capital was available to meet the rapid expansion of US procurements occasioned by the Korean War led to a loosening of monetary controls as the Japanese government set up several banks to provide low-interest loans to industry. From the very beginnings, it was clear that the policy of ‘overloaning’ alone could not solve the capital shortage and ensure the industrial reconstruction of Japan. Since the Dodge Plan mandated balanced budgets, the Japanese government sought to overcome capital scarcity through the creation of new government-owned banks and the expansion of existing ones. The two major sources of funds for these financial institutions initially came from the US ‘counterpart funds’ – or the revenues in yen obtained from the sale of US aid that were held in a special account – and from the government-operated postal savings accounts. Once the Occupation had ended, the government empowered the Japan Development Bank to raise capital by issuing its own bonds, and sought to ensure the growth of deposits in the postal savings accounts by exempting the interest on the first ¥3 million of each account from taxes. As individuals could open accounts in multiple post offices, each of which was tax-exempt up to this ceiling, these accounts grew exponentially. Simultaneously, the government consolidated the postal savings accounts into a large investment account – the Fiscal Investment and Loan Plan (FILP) – which became, since 1953, the single most important source of finance for development, ranging from one-third to one-half of the general budget and not subject to legislative scrutiny until 1973 (Johnson, 1982: 207–8, 210; Eccleston, 1989: 49; Pempel, 1998: 67).

Between 1953 and 1961, over and above indirect support to industry through government loan guarantees, the government supplied between 19 and 38 percent of all capital. This support was especially critical in regards to strategic industries – electricity generation and power supply, ships and shipbuilding, coal, and steel – which accounted for 83 percent of disbursements by the Japan Development Bank. The elimination of risk in designated growth sectors by government guaranteed loans was reinforced by the tight controls exercised by the Finance Ministry over all interest rates, bank operations, and dividend rates. Since even permission to open new branches had to be obtained from the ministry, bank managers had to concentrate only on expanding the bank's share of loans and deposits (Johnson, 1982: 206–11).

Perhaps the most important consequence of the policy of overloaning was the creation of bank-led keiretsu (industrial conglomerates) in place of the zaibatsu based on family-owned holding companies. Capital shortages had encouraged each enterprise to establish close ties with a particular bank because even if

it did not necessarily get all the money it needed or preferential terms from its primary bank … it did get one thing it could not do without – access to capital in the first place because it was an established customer. The banks in turn became dependent upon the financial health of their heavily indebted priority industries and therefore took responsibility for them.

(Johnson, 1982: 205)

Apart from banks, industrial firms also re-established ties in the 1950s to the old zaibatsu trading companies that had been broken up by the occupation forces. With the end of the Occupation in 1952, the government repealed antimonopoly laws over the protests of small- and medium-scale businesses, and MITI actively encouraged the recomposition of prewar industrial conglomerates on a new foundation. The ministry's policy of ‘keiretsu-ization’ even led its Industrial Rationalization Council to assign industrial enterprises to a trading company (sogo shosha) if an alliance had not already been established. The ministry also used its licensing powers and control over preferential financing to reduce the numbers of trading companies from 2,800 at the end of the occupation to about 20 massive ones, each associated either with a bank-led keiretsu or a constellation of smaller firms (Johnson, 1982: 205–6; Borden, 1984: 164).

Crucially, the creation of cartels and bank-led industrial groups led to the mobilization of capital on a scale adequate to create competitive enterprises in the more technologically-sophisticated sectors. The pace of consolidation in the 1960s and 1970s was so extensive that by 1974 ‘five corporations or fewer controlled 90 percent or more of the markets in the steel, beer, nylon, acrylic, aluminum ore, automobile, and pane glass industries’ (Pempel, 1998: 94).

The combination of the policies of overloaning to strategic sectors and government facilitation of alliances between large banks, industrial firms, and trading companies led to the creation of what is often called ‘one set-ism,’ or the formation of a full complement of designated growth industries within each keiretsu group to prevent being excluded from virtually risk-free sectors. Each of the six main banks – Dai Ichi Kangyo, Fuji, Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Sanwa, and Sumitomo – for instance, established ties with a major automobile company: Isuzu, Nissan, Mitsubishi, Toyota, Daihatsu, and Mazda respectively. This led to fierce competition and to inevitable overproduction as each group sought to maximize its share of government-guaranteed loans (Johnson, 1982: 206–8; Yoshino and Lifson, 1986: 33; Morales, 1994: 100–1; Gerlach, 1989; Hamilton and Biggart, 1989: S57–8; Yonekura, 1993: 211–13).

In short, the Japanese bureaucracy and big business forged an alliance to resuscitate the economy after its wartime devastation. The bureau-cracy's control over vital foreign exchange and the mobilization of domestic savings through FLIP enabled MITI and the Ministry of Financeto strategically target specific sectors for accelerated growth by providing loans at preferential rates. If capital shortages fostered close coordination between enterprises, the bureaucracy used its financial leverage to reinforce these tendencies and create large units that could reap the economies of scale.

South Korea and Taiwan

Despite their shared heritage of Japanese colonial occupation, postwar regimes in South Korea and Taiwan were reconstituted on very different foundations, though both had very narrow bases of support and were almost entirely reliant on their bureaucracies and their coercive forces. Since the American occupation forces chose to work with the Korean Democratic Party (KDP), the most conservative faction, it provided an avenue for the privileged landed aristocracy, the yangban, to reemerge as the elite of the new order in South Korea (Cumings, 1981: 97; Amsden, 1989: 36–7). If this provided continuity in government personnel, the reconstituted Korean colonial bureaucracy was ill-equipped to promote economic development because the Rhee government lacked both the technical expertise for guided industrialization and a mass mobilizational party to establish its domination over civil society.

In contrast, as the GMD was staffed by a large cadre of experts with considerable expertise in industrial production and economic planning on the Chinese mainland, the regime's higher degree of autonomy from domestic classes in its island redoubt reinforced the strength of the state apparatus. If the GMD party-state thus had more policy instruments and options to pursue a dirigiste policy than most other states, Chiang's preoccupation with returning to the Chinese mainland meant that economic growth was assigned a low priority. Hence, though the Taiwan Production Board was established in May 1949 to stabilize the chaotic conditions following his retreat to the island, and its functions expanded early the following year with the creation of an Industrial and Financial Committee, there were no serious attempts to address the issue of economic growth before the Korean War.

When Chiang's fiction of maintaining that the GMD was the legitimate government of all of China and the consequent duplication of ministries at the ‘national’ and ‘provincial’ levels blurred lines of responsibility, the creation of two supra-ministerial agencies and the parallel bureaucratization of US aid disbursements shaped a distinctive political economy of development in Taiwan. These agencies – the Economic Stabilization Board (ESB) and Council on US Aid (CUSA) – chaired by the prime minister and composed of the key ministries and departments, provided a platform for technocrats to operate unimpeded by inter-departmental struggles for control of policy. Vested with a formidable array of powers – control over industrial development, monetary and banking policies, foreign trade and the allocation of foreign exchange, military spending, budget and taxation, agriculture and price stabilization, and utilization of US aid – the ESB was far more capable of monitoring the pulse of the economy and selectively targeting specific sectors than any comparable regulatory body in the Rhee administration. Indeed, precisely because state assets in South Korea had been sold at heavily discounted prices to political supporters of the regime, no elite bureaucratic organ was created to oversee the economic performance of firms. Hence even as ‘entrepreneurs’ were abjectly dependent on state patronage for access to aid allocations and privileged exchange and interest rates, the South Korean regime was quite unable to monitor their performance, as indicated by the widespread practice of ‘entrepreneurs’ selling their foreign currency allocations and industrial licenses to the highest bidder.

The ESB in Taiwan also emerged as the arena to reconcile differences between hardline conservative elements in the GMD hierarchy who remained hostile to the development of a powerful bourgeoisie among the indigenous islanders and US aid officials advocating the creation of a strong private sector. At the same time, as hopes for a triumphant return to the mainland receded by the end of the Korean War, Chiang's administration recognized that economic growth was a better guarantee for its long-term survival since it could dilute indigenous islanders' resentment of their political and economic domination by mainland émigr ées. Given these considerations, the regime and its US advisors sought to channel funds toward the promotion of agriculture and the creation of infrastructural projects that would encourage the broadest possible expansion of industrial production as long as the units of capital accumulation remained ‘small and until the point where its transactions involve the external world’ (Wade, 1990: 268).

The promotion of rural development assumed cardinal importance not only because the party hierarchy attributed their humiliating defeat on the Chinese mainland to the exploitation of the peasantry by the landlords with whom the party was closely identified (Gold, 1986: 68; Wade, 1990: 82, 246–8, 260), but also because technocrats could siphon agricultural surplus toward industrial development by manipulating the terms of trade against agriculture. Greater support for agriculture – the rural sector received 21.5 percent of all US aid as opposed to 15 percent for industry (Jacoby, 1966: 50–1; Cheng, 1990: 45) – consolidated the GMD party-state's hold on the small peasantry while ensuring that the native Taiwanese did not pose a credible threat to the economic dominance of the émigr ées. Support of the farm sector also satisfied the demands of US advisors that aid disbursements be more equitably shared while manipulation of the terms of trade was tantamount to a recycling of these funds to industry (Ho, 1978; Simon, 1988a: 148; Wade, 1990: 82–4).

In these conditions, the shift to project-specific grants which gave Agency for International Development (AID) officials greater control over their disbursements strengthened the tendency toward a relatively even regional distribution of funds within the island. Thus, almost two-thirds of all non-military assistance were allocated to the development of infrastructural projects – in power generation, transportation, communications, and education – which generated substantial external economies and provided the framework for the emergence of a broad base of consumer goods industries in the private sector, especially in such key sectors as plastics, rayon, glass, soda ash, and hardboard. American prodding also led the government to establish the Industrial Development and Investment Center and the China Productivity Center in 1960 to promote the growth of the private sector, convert the system of multiple exchange-rates to a single rate, and ease restrictions on foreign trade to encourage foreign private investments (Jacoby, 1966: 134–8; Ho, 1978: 195–7; Gold, 1986: 69, 76–8; Koo, 1987: 168; Haggard and Cheng, 1987: 115; Simon, 1988a: 148–50; Wade, 1990: 52–3, 202; Bello and Rosenfeld, 1990: 238).

Whereas only a few indigenous Taiwanese entrepreneurs – like the journalist Wu San-lien, who fronted the Tainan Textile Corporation for several business men from Tainan, or the five largest former landlord families who controlled the Taiwan Cement Corporation – had benefitted because of their ties to the GMD before economic conditions had stabilized in the island in the mid-1950s, these measures led to the emergence of a new breed of entrepreneurs among the indigenous islanders by the end of the decade. This was not, however, indicative of a loosening of state controls over the economy. In the first instance, though some of these entrepreneurs – such as Wang Yung-ch’ing and Lin Tin-sheng – were to become major players in their own right, public enterprises still received the bulk of aid allocations: 67 percent of the assistance to the industrial sector as a whole, as opposed to 27 percent for mixed enterprises and only 6 percent to private firms (Gold, 1986: 71–3, 82; Gold, 1988b: 189; Wade, 1990: 91; Bello and Rosenfeld, 1990: 237–40). In the second instance, government control over the banking sector ensured the party-state's control over credit allocations as well as enhancing its ability to channel domestic savings toward priority sectors, especially to enterprises controlled by the GMD. Finally, the extent of state control over domestic sources of finance did not end with government ownership of the banking sector as firms required prior approval from the Securities and Exchange Commission, an agency with wide discretionary powers, to raise capital by issuing shares.

The difference between the broad-based and increasingly autonomous and self-generating development in Taiwan, and the comparatively narrow-based and heavily aid-dependent South Korean trajectory was manifestly evident by the end of the 1950s. Within five years of the end of the Korean War, US aid officials were confident enough of the reconstruction of the Taiwanese economy to begin a gradual phase out of assistance. Despite exceptionally high rates of growth, there was no such complacency regarding South Korea. Given the generalized venality of state and business elites in South Korea, the tapering off of American assistance – after peaking at $383 million in 1957, US economic aid fell to $321 million in 1958 and to $222 million in 1959 (Woo, 1991: 46, table 3.1, 72) – precipitated a sharp decline in growth rates as it undermined the provision of subsidized credit to industry. By another measure, per capita income in South Korea in 1960 was only $62 – the same as in Japan in 1868 (in 1960 prices) – and lower than in Ghana, Senegal, Liberia, Zambia, Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Peru (Hart-Landsberg, 1993: 26; Mason et al., 1980: 181; Cumings, 1987; Amsden, 1989: 41; cf. Wade, 1992: 277, n. 21).

Growing economic pressures added fuel to the fire of a student-led opposition to the authoritarian Rhee government, leading ultimately to the military coup on May 16, 1961. If issues of political stability and national unification had dominated the agenda of the Rhee administration, rapid economic growth dominated the agenda of the military junta, particularly since students and the urban middle-class had spearheaded the ouster of the former regime and the countryside had remained quiescent (Koo, 1987: 169). Or as Alice Amsden (1989: 49) pithily puts it: ‘If the lesson that the United States learned from the Korean upheavals was the need for stability before growth, then the military learned that causality ran in the opposite direction, from growth to stability.’

The changed priorities of the new regime entailed a restructuring of government organization and the institutional conditions for capital accu-mulation more generally. Within five months of the coup, the military government established comprehensive controls over the financial infrastructure and capital flows by re-nationalizing commercial banks, subordinating the Bank of Korea to the Ministry of Finance, and forming two new state-owned financial institutions, the Medium Industry Bank and the National Agricultural Cooperatives Federation. In addition, the functions of the Korean Development Bank were enlarged to enable it to borrow from overseas sources and to underwrite foreign loans of domestic enterprises (Kuznets, 1977: 78; Amsden, 1989: 16, 72–3; Woo, 1991: 51–2, 84). As a result, by 1970, the government controlled an astonishing 96.4 percent of the country's financial assets (Bello and Rosenfeld, 1990: 51).

While these changes had some similarities with Taiwan, there were also marked contrasts reflecting differences in the balance of class forces in the two jurisdictions and in the nature of their regimes. The most notable feature of the reconstitution of political power in South Korea after the coup was a greater centralization and concentration of power in the executive. As in Taiwan, the regime created a pilot agency, the Economic Planning Board (EPB), which controlled the national budget, foreign investments, and government guarantees of overseas loans. Its mandatory powers were augmented by the fact that its chief chaired the Council of Economic Ministers and since 1963 was also designated deputy prime minister. However, the creation of two secretariats in the Blue House – the presidential mansion – and of a Board of Audit and Inspection which reported directly to the president provided independent checks on the EPB. These measures were accompanied by a reorganization of government ministries, with the Ministry of Trade and Industry being charged with the promotion of exports and controls on imports, plans for industrial development, industrial licensing, approval of applications for investments and the designation of strategic projects and firms; the Ministry of Finance with the regulation of all financial institutions, tax assessment and collection, and foreign exchange; and the Ministry of Construction with infrastructural development (Cumings, 1987: 72; Johnson, 1987: 154; Haggard, 1990: 64–5; Hart-Landsberg, 1993: 48–50, 54).

If this reorganization of the government apparatus enabled the new regime to monitor economic activities on an almost daily basis, the creation of watchdog agencies that bypassed the elite bureaucracy underlined President Park's inability to create a mobilizational party modeled on the GMD. When the failure of his Democratic Republican Party to become a mass-based party became evident in the elections of 1963, which Park won only narrowly, organs of the state began to function as substitutes for front organizations of a mass party. Among these, the most prominent was the Korean Central Intelligence Agency which combined internal and external information-gathering capacities and vastly augmented the surveillance capabilities of the state. Similarly, the new government's decision to directly appoint all the staff of local agricultural cooperatives, who had previously been elected by members, reflected an attempt to strengthen control over rural areas since fertilizers and government credit were solely distributed through the cooperatives.

Paralleling this move, the government made it mandatory for all incorporated businesses to join one of 62 producer associations which functioned as intermediaries between the Ministry of Trade and Industry and individual firms, and acted as conduits for information. Through these associations, the government was able to negotiate price controls on strategic goods and services, grant industrial licenses, and promote targeted sectors. The new government also reorganized and strengthened the powers of the Korean Foreign Traders’ Association, which had powers to arbitrate international trade disputes, grant import and export licenses, and monitor individual firms’ compliance with government trade regulations and targets. Finally, the military disbanded all labor unions and created the state-sponsored Federation of Korean Trade Unions in which all candidates for offices required government approval (Amsden, 1989: 16–18; Haggard, 1990: 62–3; Hart-Landsberg, 1993: 51–3).

Though these measures to reinforce the regulatory capabilities of the state bore striking resemblances to the measures implemented in Taiwan, differences between the two regimes were equally striking. For one thing, the uneven economic record of South Korea made it increasingly vulnerable to American pressure. When Park's freedom to maneuver had been constrained by bad harvests and high domestic inflation, increased pressures from US aid officials compelled a reluctant regime to devalue the currency in 1964, raise domestic interest rates in 1965, and normalize diplomatic relations with Japan the same year. In these conditions, the Park administration sought to reduce its reliance on American aid by vastly expanding overseas borrowing. In contrast, rather than resorting to increased overseas borrowing when US economic aid to Taiwan was being phased out in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and ceased completely in 1965, the GMD regime eased restrictions on foreign investments, which rose from 1.7 percent of gross domestic capital formation between 1952 and 1960 to 6.9 percent between 1969 and 1974 (Simon, 1988a: 149–50).

Paradoxically, a major impetus to increased overseas borrowing by the South Korean government and enterprises was the insistence by US aid officials and International Monetary Fund advisors that domestic interest rates be raised to mobilize private savings and lessen dependence on foreign borrowing. This advice was, in turn, based on the experience of Taiwan where high interest rates had led to a rise in domestic savings from approximately 5 percent of national income in the early 1950s to more than 30 percent in the late 1970s.1 However, in South Korea, a virtual doubling of domestic interest rates in 1965 rendered the cost of domestic borrowing more expensive than borrowing from overseas and reinforced the dominant position of the government, as it had amended to the Foreign Capital Inducement Law in 1962 to guarantee foreign loans and thereby eliminate the risk of default and exchange-rate depreciation. The shift to overseas borrowing was so pronounced that net indebtedness rose from $301 million in 1965 to $2.57 billion in 1970, with two-thirds of the loans in the late 1960s being from private sources, and the debt-equity ratio of manufacturing firms increased from 1:2 in 1966 to 3:9 in 1971. Put another way, by one estimate, without this tremendous inflow of foreign capital, South Korean production in 1971 would have been smaller by a third (Kuznets, 1977: 78–80; Jones and Il SaKong, 1980: 101; Frieden, 1987: 149; Amsden, 1989: 73; Cheng, 1990: 157; Hart-Landsberg, 1993: 58–9; Koo and Kim, 1992: 127–8).

The obverse side of the increasing resort to overseas borrowing in South Korea was an extremely restrictive foreign investment policy. Though the exhaustion of the ISI phase led the Park administration to slightly ease restrictions on foreign investments after 1962, such investments continued to be prohibited in many sectors and even in those sectors that were legally open to outside investors, government regulators routinely rejected applications not deemed to be in the ‘national interest.’ In practice, then, majority equity participation by foreign owned firms was seldom approved unless they were entirely export-oriented and the preferred option was to permit joint ventures with a local partner to transfer technology. As a result of these measures, FDI accounted for only 3.7 percent of net capital transfers to South Korea between 1967 and 1971 while the equivalent figure for Mexico was 36.6 percent, for Brazil 33.8 percent, and for Thailand 26.1 percent (Evans, 1987: 207; Amsden, 1989: 74–7; Bello and Rosenfeld, 1990: 54–5; Hart-Landsberg, 1993: 86–90).

Complementing these restrictive policies on overseas investments were stiff import tariffs which were retained even after the exhaustion of the ISI strategy. Though quantitative controls on imports were gradually eliminated, the imposition of special tariffs since 1961 to absorb the differential between domestic prices and landed cost of imports implied a steep increase in the average legal tariff. Similarly, the shift from a positive list system whereby listed goods could not be imported without explicit government permission to a negative list system when listed goods were automatically approved for import in 1967 masked a variety of practices which sharply restricted the range and volume of imports – and the share of freely importable goods in total imports declined from 55.6 percent in 1968 to 46.7 percent in 1974 and to 38.8 percent in 1978. By another measure, it has been estimated that, even as late as 1990, less than 3 percent of imports could be classified as luxury goods (Kuznets, 1977: 153–4; Krueger, 1979: 89–92; Mason et al., 1980: 128–32; Bello and Rosenfeld, 1990: 52–3; Hart-Landsberg, 1993: 37, 78–81; Haggard and Moon, 1993: 72–3).

The choice of foreign investments over increased overseas borrowing in Taiwan and the opposite in South Korea reflected fundamental differences between the two regimes. The failure of the military regime to institutionalize itself through the creation of a mass mobilizational party on the lines of the GMD led President Park to attempt to substitute economic performance for organizational capacity as the basis for political legitimacy (Cheng, 1990: 159). Once economic growth assumed priority, it was imperative that an alliance be established with the largest firms since ‘the only viable economic force happened to be the target group of leading entrepreneurial talents with their singular advantage of organization, personnel, facilities and capital resources’ (Kyoung-dong Kim quoted in Haggard and Cheng, 1987: 111).

The emerging ‘sword-won’ alliance between the junta and leading industrialists in South Korea was, however, based on an entirely different foundation from the alliance instituted under the Rhee regime. By virtue of its stranglehold over the financial infrastructure, the government was able to shape the direction of industrial production through the allocation of subsidized capital, credit guarantees, and favorable – even negative – interest rates to targeted firms and industries.2 As a result, the debt-equity ratio of firms in South Korea averaged between 300 and 400 percent in the 1970s when compared with 100 to 200 percent for Brazilian and Mexican firms or 160 to 200 percent for firms in Taiwan. Moreover, by 1981, over 200 types of policy loans – targeted for specific industries at rates lower than the already highly discounted rates, and over which the banks had no control – had evolved to further promote specific types of manufacturing activity (Woo, 1991: 12). By virtue of its control over industrial licensing, the government could also reward firms entering sectors with long-fruition lags or high risks with licenses in the more lucrative sectors. Due to the higher technical requirements of targeted sectors, and the emphasis on increased exports, the regime tended to favor larger firms often controlled by political supporters: the Ssangyong group in cement rather than the more established Tongyang Corporation, for example, or the state-owned Pohang Iron and Steel Company, or the Hyundai group in shipbuilding, or the trio of Hyundai, Samsung, and Daewoo in the machine building sector (Amsden, 1989: 14–18, 73).

However, in return for privileged access to capital and industrial licenses, the government imposed stern discipline, most often related to export targets. Export-related criteria assumed preeminence in assessing enterprise performance both because continued improvement in exports provided a reliable indicator of efficiency and because tight control over the allocation of industrial licenses and cheap credit and high debt to equity ratios rendered financial indicators a poor guide. To increase market share overseas, firms were not only provided with a variety of subsidies – including lower taxes on export earnings, accelerated depreciation allowances, and duty-free imports of selected capital and intermediate goods – but were also allowed to sell products at inflated prices in domestic markets to partially off-set the costs of dumping products abroad. At the same time, the government imposed restraints on the market power of large conglomerates by negotiating price controls annually, and as late as 1986 some 110 commodities ranging from flour and sugar to automobiles and chemicals were subject to such controls (Kuznets, 1977: 156–62; Krueger, 1979: 92–9; Amsden, 1989: 17. 144–51; Bello and Rosenfeld, 1990: 52–3).

If secure access to cheap credit and a battery of incentives encouraged chaebol to pursue expansion into areas with long-fruition lags and high risks, it heightened their dependence on the government and the regime did not hesitate to dismember firms that failed to fulfill their export targets or other performance criteria without plausible excuses. Even the very largest conglomerates were not immune to such sanctions, as indicated by the experience, for instance, of the Shinjin company which had a larger share of the domestic automobile market than Hyundai in the 1960s. However, as Shinjin could not survive the oil crisis of the early 1970s and competition from Hyundai's ‘Pony,’ its credit lines were cut and the government, in its role as banker, transferred the company's assets to Daewoo Motors (Amsden, 1989: 15; Bello and Rosenfeld, 1990: 70–1; Hart-Landsberg, 1993: 69–70; see also Cumings, 1987: 74). In this context, it is significant that though the government imposed strict discipline on the chaebol and had no hesitation in dismembering and cannibalizing poor performers, business failure did not lead to unemployment as assets were simply transferred to other politically better connected conglomerates (Amsden, 1989: 15, 139–55; Eckert, 1993: 102–4).

With the rapid increase in exports and the emergence of successful entrepreneurial groups there was both a greater stratification of wealth in Taiwan and the emergence of wealthy indigenous islanders. By 1983 seven of the leading ten leading business groups were led by native Taiwanese (Bello and Rosenfeld, 1990: 238–9). Equally importantly, the predominance of small- and medium-scale firms and their spatial dispersal across the island,3 provided a relatively even regional development of industrialization on the island, with the obvious exception of the EPZs. The percentage of industrial employment in the five big cities, for instance, declined from 36.8 percent in 1966 to 22.8 percent in 1986, while it rose correspondingly in the four suburban regions from 31.9 percent to 45.8 percent. The increasing dispersal of industrial production was reflected in the decline of their unit size. While the average size of industrial plants in the five big cities declined from 26.9 employees in 1966 to 21.6 employees in 1986, it remained relatively stable in the four metropolitan regions, falling from 25.8 in 1966 to 25 in 1986, and rose from 13.5 to 21.8 in the twelve rural regions (Deyo, 1989: 20–1, 41; Amsden, 1991: table 6; see also Cheng and Gereffi, 1994: 210).

In sharp contrast, one important consequence of the strategy of ‘betting on the strong’ firms in South Korea was the progressive growth of regional imbalances. Ironically, reflecting their rural background, the military junta had initially attacked the illicit accumulation of wealth under the First Republic, and demonstrated a marked bias toward agriculture. Almost immediately after the seizure of power, they liquidated most of the farm debt and shifted the terms of trade in favor of farm produce so that rural and urban incomes were on par by 1965. However, once emphasis shifted toward rapid industrialization, the centralization and consolidation of political power in the executive and the concentration of economic power in the chaebolmeant that despite Seoul's proximity to one of the most volatile political frontiers of the Cold War, urban and industrial growth was skewed toward the capital city where more than 96 percent of all firms were headquartered. Another pole of industrial concentration, reflecting the high dependence on imports and exports and the need to lower transportation costs, has been the Pusan–Kyongsang corridor on the southeastern coast. The polarization toward these two nodes is indicated by decline of population in the Cholla provinces on the southwest seaboard, falling from some 25 percent of the population in 1949 to 12 percent in 1983, and its share of manufacturing employment showed similar decline, falling from 13.1 percent in 1958 to 5.4 percent in 1983. In contrast, the population of the Kyongsang provinces rose from 28 percent of the total in 1949 to 30 percent in 1983 and its share of manufacturing employment from 28.6 percent in 1958 to 40.1 percent in 1983 (Chon, 1992; Douglass, 1993b).

Clearly, the polarization of industrial production toward these two industrial nodes was a result of the greater emphasis placed on industrial production at the expense of the rural sector. Due to the concentration of investments in these growth poles and the predominance of large-scale industries, employment opportunities were not only disproportionately greater in Seoul and the Pusan–Kyongsang corridor, but the pattern of investments had the effect of precluding the development of small- and medium-scale industries in the rural areas. Moreover, for those without land, re-entry to the farming sector was difficult (Cheng, 1990: 160–1; Deyo, 1990: 195).

Regional imbalances, however, reflected more than merely the subordination of agriculture to the state-led industrialization drive. The Kyongsang provinces provided the political base of the military junta and 32 percent of government officials from 1961 to 1986 were recruited from these provinces. Similarly, the founders of nine of the top 20 chaebos also came from these provinces. Conversely, as the Cholla provinces, the richest agricultural zone in the country, declined in relative terms, it became the center of resistance to the military (Chon, 1992).

Briefly put, however much Taiwan and South Korea may have inherited a shared legacy of Japanese colonialism, differences in the constitution of their postwar regimes, and the adoption of different patterns and tools of state intervention led to sharp divergences in their economic structure:

The logic of the Korean approach – hierarchical, unbalanced, and command-oriented – calls for the intensive use of resources to foster a highly select and obedient business sector to carry the specific tasks the leadership may assign. The logic of the Taiwan approach – horizontal, balanced, and incentive-oriented – implies the extensive use of resources to allow a more pluralistic economy within the broad parameters delimited by the state.

(Cheng, 1990: 142)

These differences in industrial structures were to have consequential consequences over time. The greater addiction of South Korean chaebolto high debt–equity ratios and debt-financed expansion made them household names the world over as they trespassed with impunity into technologically-sophisticated sectors but made them vulnerable to the vicissitudes of short-term capital markets, as amply evident by their exposure to the economic crisis that began to unravel their corporate structures in 1997. If the smaller size of Taiwanese enterprises meant that they did not enjoy the same brand name recognition, their smaller exposure to foreign loans largely insulated them from the financial crisis that engulfed the chaebol, as we shall see in Chapter 5. Conversely, the spatial concentration of industrial production endowed workers in South Korea with much greater political power than their Taiwanese counterparts.

Hong Kong and Singapore

Dirigisme in the two city-states was based on an entirely different set of conditions. The loss of their hinterlands meant that their entrepôt role was fatally compromised and their small markets, poor endowment of natural resources, and the absence of large infusions of US aid ruled out the incubation of a domestic bourgeoisie. If Hong Kong's large expatriate industrial bourgeoisie and the migration of Chinese manufacturers from Shanghai partly ameliorated its conditions, no such relief was available to the Singaporean government. Not only did they have to confront and corral a strong left-wing movement which had no counterpart in Hong Kong, but the British naval withdrawal further exacerbated Singapore's economic plight. Governments of both city-states were therefore compelled to intervene in a manner designed to transform their territories from entrepôts to off-shore manufacturing platforms and to provide conducive conditions for foreign investments.

In Hong Kong, there was a great degree of cohesion between government and business elites as evidenced by the fact that all major legislation was circulated in draft form to the main employers associations – the Federation of Hong Kong Industries, the Chinese Manufacturers' Association, the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, and the Employers' Federation of Hong Kong. While the General Chamber, dominated by the big British ‘hongs,’ even nominated one of the members to the Legislative Council, similar privileges were not accorded to the labor unions that were not represented on the Council. However, employers' associations rarely acted in concert. The sheer numbers of small firms – there were 141,708 establishments in 1981, of which 47,996 were in manufacturing – made consensus difficult while the political weakness and fragmentation of labor meant that there was little incentive to close ranks. Besides, close interrelationships between major firms and their informal ties to the colonial administration made it possible for them to safeguard their interests without recourse to the larger associations (Deyo, 1989: 14, 43–5; England and Rear, 1975: 12; Lethbridge and Ng Sek-Hong, 1993: 92–5).

While the British government appointed the governor and all senior officials in the Crown Colony, and nominated all official and unofficial members of its Executive and Legislative Councils and had the power to override local laws, local officials had almost complete autonomy in practice and the last time the parliament at Westminster overruled local laws in Hong Kong was in 1913. Apart from foreign affairs, citizenship, and landing rights for aircraft (which enabled British airlines to negotiate reciprocal rights with airlines in East and Southeast Asia), laws were enacted entirely by local officials, even though the Governor was theoretically vested with almost unlimited powers – subject only to the stipulation that he consult with the Executive Council composed of six senior officials and eleven nominated unofficial members. In practice, laws were passed by the Legislative Council. Close links between the officials, who often serve a longer term than the governor's five-year stint, and directors of major corporations led to a great deal of social cohesion among the government and business elites, as indicated by the appointment of top government officials, after their retirement from the civil service, to key executive positions in employers' associations.

By shouldering the costs of infrastructural development and subsidizing wage-goods, the colonial government provided conditions conducive to an expansion of low-cost manufacturing activities. The very success of these policies led to greater state involvement in the economic arena as the rapid rise of cheap exports from Hong Kong led to the imposition of quotas on their exports by the governments of the United Kingdom, the United States, and other high-income states from the late 1950s. Beginning with the textile industry, and subsequently expanding to an increasing number of sectors, the impositions of quotas prompted the colonial administration's Industry Department to set quotas for individual firms to ensure that Hong Kong's global quotas would be equitably shared between the major firms. However, though the government had initially allocated quotas on the basis of installed capacity, the quotas soon became tradable commodities between textile mills and garment manufacturers (Lau and Chan, 1994: 116; Miners, 1993: 110–11; Castells et al., 1990: 90–1, 119–21; Yeung, 2000: 144).

Despite protestations of non-interference in the economy, the precariousness of the small-scale industries on which its export production was based encouraged the colonial administration to provide a variety of services to these firms that they could not otherwise obtain for themselves. Thus, beginning in the mid-1960s, as other low- and middle-income states began to attract foreign investments and to abandon ISI policies for reasons more fully explored in the next chapter, the Hong Kong government established a number of public agencies – most notably, the Hong Kong Tourist Association, the Hong Kong Trade Development Council, the Hong Kong Export Credit Insurance Corporation, and the Hong Kong Productivity Council – to provide commercial intelligence, personnel training, legal and technological assistance, and insurance for high-risk ventures for small- and medium-scale enterprises. Collectively, these measures amounted to an ad hoc industrial policy until 1979 when the government formulated an explicit industrial strategy to upgrade the technological level of industries as well as to transform Hong Kong into a financial service center (Castells et al., 1990: 90–1).

The absence of a strong domestic bourgeoisie imbued dirigisme in Singapore in shades of a very different color. Rather than seeking to incubate or revive a home-grown class of entrepreneurs, government policies were fashioned to attract foreign investments to transform the island-state into an offshore manufacturing platform. Such investments also served to preclude the emergence of domestic Chinese capital as an alternate base of power as well as ensuring that Western powers had a stake in Singapore's survival. Once the militancy of labor had been curbed and steps taken to reduce the costs of reproduction through public housing schemes, the government moved to create an institutional framework to entice foreign investors. Toward this end, and given Singapore's relatively high wage structure, the government offered foreign investors a raft of incentives: reduction of taxes on the profits of exports of manufactured goods to one-tenth of the standard corporate rate; exemption of machinery, equipment, and raw materials required for industrial production from all import duties; unrestricted repatriation of profits; and generous depreciation allowances (Rodan, 1989: 87; Bello and Rosenfeld, 1990: 291–3; Haggard, 1990: 111).

As in other developmental states, the EDB determined industrial policy and aimed to target sectors of increasing technological sophistication for accelerated growth. However, rather than nurturing domestic industries, the EDB assessed applications for ‘pioneer industry status’ which enabled designated sectors to receive low-interest loans, tax holidays, and other special privileges (Haggard, 1990: 113). The institutional scaffolding for the more efficient implementation of these policies was provided by a range of specialized agencies: the Jurong Town Corporation created in June 1968 to oversee the development of industrial estates and lands; the Development Bank of Singapore (DBS) in July 1968 to provide long-term finance at low-interest rates; the International Trading Company (Intraco) in November the same year to lower procurement costs of raw materials by buying in bulk and to expand overseas markets; and the Neptune Orient Lines in January 1969 to reduce dependence on foreign shipping. Finally, not content to rely solely on private capital, the government also established 13 new public manufacturing enterprises in 1968 and eight more the following year (Rodan, 1989: 94–5).

The focus on attracting foreign investments inevitably meant that the government neglected to nurture domestic entrepreneurs and this had become starkly evident by 1976 when locally-based capital in manufacturing declined from S$123.1 million or 42.2 percent of all manufacturing investments in 1974 to S$42.8 million or 42.1 percent in 1976. Consequently, the government launched the Small Industries Finance Scheme in 1976 to advance low-interest loans for the establishment of small industries and for the diversification of existing ones. However, since protectionist measures would contravene the primary strategy of attracting large foreign investments, the intent behind small industry promotion was to create synergies between local industries and the TNCs to create fully integrated industrial sectors, especially in the electronics industry. The expansion of Japanese subcontracting networks in the 1970s limited the success of this strategy since low-cost suppliers were emerging in neighboring locations as limitations of narrow domestic markets in Malaysia and Thailand, ethnic conflicts in Malaysia, and the oil boom in Indonesia led to an opening of these economies at the same time. As these tendencies led to a less than expected degree of integration in the manufacturing sector, the Singaporean government introduced the Product Development Assistance Scheme in 1978 to boost research and development capabilities of local firms (Rodan, 1989: 124–5).

Just as different socio-political constitutions led regimes in South Korea and Taiwan to shape distinct political economies on their shared legacy of Japanese colonialism, so too did the governments of Hong Kong and Singapore shape distinct political economies on their shared legacy of British colonialism. Despite their differences though, the reintegration of these economies into the post-Second World War world market exhibits some striking parallels. The fallout of the Chinese Revolution prompted the GMD regime in Taiwan and the British colonial administration in Hong Kong to promote or subsidize small-scale manufacturing to accommodate refugees from China, as well as to broaden the regime's constituency among the indigenous islanders in Taiwan and to compensate for the Crown Colony's loss of its hinterland. A different dynamic shaped the political economy of South Korea and Singapore. Confronted by the need to quickly incubate a domestic bourgeoisie and also to bolster its support base, the Rhee administration sold off expropriated Japanese assets to its supporters. Reckoning that reliance on the big conglomerates will yield quicker results, the Park regime continued to support them even in the face of opposition from US aid officials. Without the influx of manufacturers that conditioned Hong Kong's transformation into a locus of low-cost manufacturing, the Lee administration in Singapore sought to entice large foreign investments as manufacturers in Western Europe and North America faced increasing competitive pressures in their home bases. Finally, while the resuscitation of the Japanese economy also led to the revival of large-scale enterprises, these were tied in a symbiotic relation-ship to small- and medium-sized enterprises, as we shall see in the next section.

Patterns of industrial organization

By the early 1980s, when economies strung along the Asian rimlands registered the fastest rates of growth, several analysts attributed these high growth rates to the ‘Confucian family values’ they shared, including the subordination of sectoral interests to the larger national interest, the respect for education, and the predilection for hard work. The spectacular rise of Japan was said to spring from the three ‘sacred pillars’ of its dominant pattern of employment relations – lifetime employment, seniority wage system, and enterprise unionism. It was suggested that stability of employment provided the basis for cooperative relations between workers and management while seniority wages replicated family hierarchies and by providing an array of benefits (from housing to holiday travel), enterprise-based unions reinforced the image of company-as-family. However, closer examination revealed that Japanese corporations provided long-run employment rather than lifetime employment and that this was also the case with large, well-managed corporations elsewhere. Small enterprises, which constitute the overwhelming majority of firms in Japan and else-where, were never able to provide similar conditions of employment nor were they able to provide welfare benefits on the scale of enterprise unions of large corporations (Aoki, 1987).

Nevertheless, industrial structures and employment relations in these economies evolved along lines markedly different from the normative Euro–North American patterns. Unlike in the United States, for instance, where hiring can take place at any time during an individual's career trajectory and is done in a decentralized manner, Japanese firms tend to hire at graduation through a centralized personnel department. However, while Japanese workers can more easily change jobs within the firm once they are hired, US workers tend to get locked into specific job categories. Finally, while US workers tend to be paid by skill and job classification and only secondarily by seniority, workers in major Japanese corporations tend to be paid according to seniority rather than by job classification, but seniority was never a sacrosanct principle in Japan when layoffs were concerned (Morales, 1994: 54). Yet, as briefly alluded to in Chapter 2, rather than being traditional, these employment practices were the outcome of management strategies to improve labor productivity and union attempts to improve the status of industrial workers and their working conditions in the 1950s (Gordon, 1985; Shapira, 1993: 242).

The greater job security enjoyed by workers in major Japanese corporations was also due to the maturity of the working class. Elsewhere along the rimlands, where industrial working classes were constituted after the Second World War, the ideological offensive against ‘communism’ generated by the wars in Korea and Vietnam and the very different institutional structures of accumulation conditioned employment conditions. Though workers in colonial Korea had a tradition of militancy, war and partition had so decimated the old working class that workers in the postwar era were recruited from the countryside and virtually none of them had prior experience in wage-employment (Koo, 2001). In Taiwan and Hong Kong, on the other hand, the predominance of small-scale industries led to a reconstitution of patriarchal, family-based workshops that often generated a new gender politics articulated in the idiom of familial values (Greenhalgh, 1994). While a full discussion of these patterns of employment relations and the forms of resistance they generated is outside the purview of this chapter, we seek to sketch dominant patterns of industrial organization in which workers were embedded in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, and Hong Kong and Singapore. Complementarities and differences between industrial structures in these jurisdictions conditioned the emergence of regional networks of trade, production, and investment charted in the next two chapters. Thus, this integration of studies on their varied characteristics provides an essential background to our analysis.

Japan

When the Japanese government after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 embarked on a crash program of industrialization, they created several key institutional innovations, perhaps the most notable of which was the sogo shosha or general trading company. These were diversified enterprises with interests ranging from procurement, financing and transportation of capital goods and raw materials to the distribution and sale of finished goods. With their vast network of agencies, the sogo shosha established alliances with the zaibatsu, serving as their primary if not exclusive distributors, and fledgling industrial ventures to reap economies of scale in the purchase of raw materials. The sogo shosha's large network of procurement agencies and distribution outlets provided critical market intelligence and freed their client firms from bearing the costs associated with maintaining such systems of their own. Even after the US occupation forces began dismantling monopoly houses – including the two largest sogo shosha, the Mitsui Bussan and the Mitsubishi Shoji – senior executives of the former companies were aware of the benefits that would accrue from pooling their resources and as soon as the Occupation ended, the Japanese government facilitated the reconsolidation of the sogo shosha. By virtue of its diversified activities a sogo shosha could spread costs over a number of transactions and thereby lower unit costs for its member firms. Its ready access to raw materials, markets, and information could reduce risks and monitor price movements far better than any one of its client firms, no matter how large, could do by themselves. Banks also preferred lending directly to sogo shosha as it freed them from processing a large number of small loans while a sogo shosha's intimate knowledge of market conditions and a firm's creditworthiness reduced risks of default (Yoshino and Lifson, 1986). Yet, since the client firms were independent entities, they were not necessarily tied to one sogo shosha and may indeed sell their products to outside firms or to clients of rival sogo shosha.4 At the same time, each sogo shosha often included rival firms who competed with each other. Hence, as Michael Yoshino and Thomas Lifson (1986: 47) note, a sogo shosha product system 'is best understood not as a rigid body whose constituent units are mechanically linked into a tightly balanced system but as a constellation of firms active at various stages of a complex production process.' Nevertheless, the sogo shosha represented an enormous concentration of economic power with the top ten controlling between 50 and 60 percent of Japanese foreign trade and some 20 percent of its domestic wholesale trade in the 1960s (Pempel, 1998: 70).

After the premature termination of the program for zaibatsu dissolution, postwar restructuring of industrial organization in Japan was marked by two distinct forms of industrial conglomerates – the intermarket groups or kigyo shudan (for example, Dai Ichi Kangyo, Fuyo, Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Sanwa, and Sumitomo) and independent industrial groups or kaisha (for example, Hitachi, Industrial Bank of Japan, Matsushita, Nippon Steel, Nissan, Tokai Bank, Tokyu, Toshiba-IHI, Toyota, and Seibu). As the name suggests, intermarket groups were horizontal coalitions of firms built around financial institutions and sogo shoshas, while the independent industrial and financial groups represented vertically integrated firms in one or more sectors built around a large parent company. In both cases, control over affiliated firms was established through interlocking stock ownership, though the degree of control exerted tended to be stronger among intermarket groups than among firms within the independent groups. Though the six major horizonal keiretsu represented only 0.1 percent of all the companies in Japan, they accounted for almost 25 percent of the total value of shares in the Tokyo Stock Exchange (Eccleston, 1989: 40–1; Hamilton and Biggart, 1989: S57–9; Glasmeier and Sugiura, 1991: 399–401; Pempel, 1998: 70).

Even if horizontal linkages between financial institutions, industrial firms, and commercial organizations through interlocking shareholding, lender–borrower, buyer–seller, and director relationships provided the institutional base for the reconstruction of the Japanese economy, the scalar magnitude of US military procurements at the start of the Korean war was so extensive that major firms sought to utilize idle productive capacities of parts manufacturers by sourcing out components (Smitka, 1991: 6–10, 53–78; Eccleston, 1989: 35; Glasmeier and Sugiura, 1991: 399). As wage workers constituted only 39.3 percent of the working population at the onset of the Korean War (Itoh, 1990: 145), this strategy was seen as a temporary expedient especially since the length of the war-induced boom was uncertain. Large firms, however, soon abandoned their efforts to recreate their prewar structure of vertically integrated production systems as the advantages offered by stable subcontracting arrangements rapidly became evident.

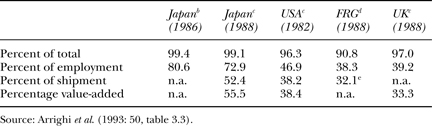

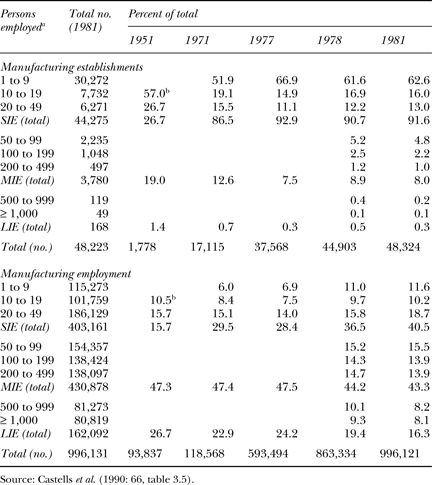

From these beginnings, as several theorists associated with such ungainly coinages as ‘Fujitsuism,’ ‘Toyotism,’ and ‘global Japanization’ have underscored, subcontracting arrangements in Japan evolved in a manner that contrasts sharply with similar practices elsewhere. First, as indicated by Table 3.1, though small- and medium-scale firms as a percentage of all manufacturing enterprises in Japan are approximately the same as in other core states, they account for a much higher percentage of employment, shipments, and value added to production. Correspondingly, small and medium scale enterprises in Japan were highly dependent on a few large firms and in the early 1980s over 90 percent of all subcontractors in the textile sector were found to have sold the bulk of their output to three firms or less (Eccleston, 1989: 30–1; Glasmeier and Sugiura, 1991: 401; Pempel, 1998: 71).

Table 3.1 Significance of small- and medium-sized corporations in selected core statesa

Notes

a Japan: fewer than 300 employees; USA: fewer than 250; Germany: fewer than 300; UK: fewer than 200.

b Nonprimary sector. The size of small and medium-scale corporations are: fewer than 300 employees for manufacturing; fewer than 100 for wholesale, and fewer than 50 for retail and service sectors.

c Manufacturing sector.

d Manufacturing sector, excluding hand manufacturing.

e Total sales.

Second, though Japanese manufacturers may depend on fewer primary subcontractors than vertically-integrated corporations in other high-income states, subcontracting networks are more extensive in Japan due to the highly stratified nature of these networks. Thus, whereas a typical Japanese automotive maker has 170 primary subcontracting (ichiji shitauke) firms (producing machinery such as robots, jigs, and large body panels; subassemblies like engines and seats; and major body parts such as brakes), the latter depend on 4,700 secondary (niji shitauke) subcontractors (supplying dies, metal work, small body parts, and such single components as brake linings) who, in turn, depend on 31,600 tertiary subcontractors (sanji shitauke). Below this layer are the large numbers of households where women fabricate minor parts – metal stampings of brand names, tiny electronic components, etc. (Sheard, 1983: 56; Cusumano, 1985: 250–3; Hill, 1989: 464–6; Fujita and Hill, 1993: 180–2; Morales, 1994: 108–9; Arrighi et al., 1993: 51). A government survey on the state of industry in 1976 revealed that more than 90 percent of firms employing 50 workers or more, and more than 75 percent of firms with 10 to 40 workers farmed out work to subcontractors. What was still more remarkable was that almost 50 percent of firms employing four to nine workers and one-sixth of firms with one to three workers issued subcontracting work (Sheard, 1983: 60; Cusumano, 1985: 192; Kenney and Florida, 1988: 136).

Third, instead of purchasing components under short-term contracts from a large number of suppliers, as was the norm for vertically-integrated US corporations until recently, Japanese firms built long-term relationships with a small number of primary suppliers (Smitka, 1991: 4–10, 58–88, 175–89). The continuity of these affiliative relationships enabled major Japanese manufacturers to circumvent the high transaction costs, irregular deliveries, and poor quality of parts that plague outsourcing arrangements in other core states, and in pre-Second World War Japan itself (Morris-Suzuki, 1994: 154–5; Glasmeier and Sugiura, 1991: 399). This was very different from the arm's-length, market-based, short-term contracts with independent companies that was the norm in the United States and Western Europe.

By farming out production to a large number of suppliers who have no direct relationship with each other, mass manufacturers in the United States were often confronted with incompatible parts. In contrast, by relying on a smaller number of primary subcontractors, Japanese manufacturers tended to merely specify performance requirements and leave engineering decisions to their first-tier suppliers who were responsible for an entire component (Womack et al., 1990: 60–1, 142, 146–7).