3

Human Resources Management in South Korea

Introduction

This chapter is concerned with human resource management (HRM) in South Korea (hereafter just ‘Korea’), the third largest economy in Asia and the 13th largest economy (in 2011) in the world (the 11th largest just before the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis). While at first sight it may be assumed to be a ‘typical’ Asian country in terms of its HRM, the reality is less clear-cut, with many particular practices. The key characteristics of Korean HRM revolve around practices based on ‘regulation’ (or ‘seniority’) versus more ‘flexibility’ in labour markets (with easier job shedding) and remuneration (with greater focus on performance). Paradoxically, some influences (such as globalisation) have generated a less homogenous HRM system in Korea today.

This chapter is an update of our earlier piece with the inclusion of some changes that have emerged. We add six points as new changes or trends in HRM. First, performance-based HRM has been ‘softened’ or at least not intensified. Companies began to recognise that the adoption of performance-based HRM was a double-edged weapon. Second, a job-based HRM system has been diffused, at least for certain job families (such as tellers in the banking industry). This change is related to cost-reduction strategies and the shift of status from contingent workers to regular workers. Third, workplace flexibility has been enhanced. Examples include flexitime. Other related developments include more relaxed dress codes and various benefits for younger employees, for example, the provision of break areas, tea rooms and music halls (for listening to music during break times), which are related to enhancing employee creativity through the combination of ‘play’ and work. Fourth, work–family balance has become a more critical issue. Many companies also provided various benefits for male staff (such as paternity leave). Fifth, global talent management has also become a more critical task. Large corporations have standardised job systems for cross-country mobility. Sixth, large corporations became more actively involved in benchmarking activities, at least until 2006. Fewer companies now have this kind of activity, which implies that the HRM systems of Korean firms are in their ‘mature’ stage, at least from the practice viewpoint. Since so many HRM practices have been benchmarked and adopted already, it is not an issue of the practice, but that of the functioning, of those practices.

This chapter is structured around a similar common framework and structure as others in this collection. First, the historical development of HRM is given. Second, partnership in HRM is presented. Third, the key factors determining HRM practices, such as politics, national culture, the economy, the business environment and institutions, are described, along with a review of HRM practices, such as staffing, pay, training and unions. Fourth, changes taking place within the HRM function recently and currently, and the reasons for them, are outlined. Fifth, some key challenges facing HRM are noted. Sixth, what is likely to happen to the HR function is explored. Seventh, some details of websites and current references for the latest information and developments in HRM are annotated.

Historical Development of HRM

The ‘management of people’ has a long and diverse history in Korea. This needs to be set within Korea’s sometimes traumatic history. Here we delineate the more contemporary HRM system (see Kim and Bae, 2004, for earlier periods). HRM’s evolution can be analysed within a three-dimensional framework. In this there are three critical historical incidents: the Great Labour Struggle in 1987, the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 (Bae and Rowley, 2003; Kim and Bae, 2004), and the global financial crisis of 2007–08. This produces four stages – pre-1987, 1987– 97, 1997–2007 and post-2007 – each with different HRM configurations. The HRM system can be conceptualised on two dimensions: (1) rewards and evaluation; (2) resourcing and flexibility. The first dimension indicates the basis of remuneration and appraisal, that is, seniority versus ability/performance; the second represents labour market choices, that is, internal labour markets and long-term attachment versus external labour markets and numerical flexibility. Simultaneously, we can also use Rousseau’s (1995: 97–9) typology of psychological contracts: (1) ‘relational’, with high mutual (affective) commitment, high integration and identification, continuity and stability; (2) ‘transitional’, with ambiguity, uncertainty, high turnover and termination and instability; and (3) ‘balanced’, with high member commitment and integration, ongoing development, mutual support and dynamics.

The first stage, pre-1987, was a ‘seniority-based relational’ type HRM. ‘Seniorityism’ was pivotal for various HRM practices such as recruitment, evaluation, training, promotion, pay and termination. In addition, firms generally had long-term attachment to employees, who were rarely laid off. However, the first critical incident, the Great Labour Struggle, resulted in sudden wage increases, which partly reduced competitive advantage in this dimension. This led to the second stage.

The second stage, 1987–97, was an ‘exploratory performance-based’ type HRM. Firms started to specify performance terms more. The fulcrum of the HRM system began changing from seniority more towards performance. From the early 1990s firms started to adopt ‘New HRM’ (sininsa) systems to enhance fairness, rationalisation and efficiency (Bae, 1997: 93). Many firms revamped performance evaluation systems to make them actually function. However, adjustment on the resourcing and flexibility dimension was more rarely touched.

The third stage, 1997–2007, saw a ‘flexibility-based transitional’ type HRM developing. With the Asian Crisis large corporations launched massive restructuring efforts, for example, mergers and acquisitions, management buyouts, spin-offs, outsourcing, debt for equity swaps, downsizing and early retirement programmes. In these circumstances both public and private policies focused more on labour market flexibility. Bae (forthcoming) interpreted the changes of HRM during this period with the lens of self-fulfilling prophecy. On the other hand, the performance orientation adopted from the previous stage was consolidated. Hence, a more performance-based approach was internalised by organisational members (Bae and Rowley, 2001). At first, the HRM system after the Crisis was more like Rousseau’s (1995) ‘transitional’ type. Top management and HRM professionals lost their sense of direction regarding the future of HRM. However, from the beginning of the 21st century firms started to become more like a ‘balanced’ type. This model of mutual investment and support has been adopted by large, progressive corporations, such as Samsung and LG. At the same time, firms began to utilise a dual strategy of ‘balanced’ type for core employees and ‘transactional’ type for contingent workers (Bae and Rowley, 2003).

The fourth stage, post-2007, can be characterised as ‘reflective balanced or community’ type HRM, with self-reflection on a decade of experiments of performance/flexibility-based HRM. After these experiments, many Korean companies realised that a market-like employment relationship was not really the answer. The performance/flexibility-based approach has been not that much intensified at least. For example, the Doosan Group use the term ‘softened’ (or ‘warm’) performance-based HRM (see case study in this chapter). Samsung also emphasised more the relational aspects in HRM again by changing to forms of profit sharing. Some firms thought that they may have gone too far. This may reflect the dialectical nature of organisational changes.

Partnership in HRM

Ideas of increased employee involvement and partnership have emerged at dual levels post the 1990s. Examples at the macro level include the neo-corporatist type Presidential Commission on Industrial Relations Reform (1996) and the tripartite Labour–Management–Government Committees (nosajung wiwonhoe) on Industrial Relations (1998) (Yang and Lim, 2000). At the micro level are examples such as LG Electronics, which emulated practices in plants in the United States (Saturn, Motorola) and Japan. LG Group used the concept of ‘partnership’ in its post-1998 employee relations reforms (see Park and Park, 2000). There is also a national Labour Management Council (LMC) system (Kwon and O’Donnell, 2001; Rowley and Yoo, 2008; Rowley and Bae, forthcoming).

Some indicators of employment relations, such as unemployment and real wage growth, worsened after the Asian Crisis, which the Tripartite Commission was formed to help to try to resolve. This was an unusual case given the hostile relationships among employee relations system actors and the government’s policy direction towards a more market-based approach. Since 1998 several commissions have been initiated, summarised below:

- 15 January 1998: First Tripartite Commission (15 January–February 1998) with Han Kwang-ok as chairperson held its first session.

- 6 February 1998: Tripartite Commission held the 6th session and adopted the Social Compact to overcome the Crisis and agreed on 90 items, including consolidation of employment adjustment-related laws and legalisation of teachers’ trade unions.

- 3 June 1998: Second Tripartite Commission (3 June 1998–31 August 1999) with Kim One-ki as chairperson held its first session.

- 24 February 1999: The Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) withdrew from the Tripartite Commission.

- 1 September 1999: Third Tripartite Commission (1 September 1999–26 April 2007) was launched with Kim Ho-jin as chairperson and held its first plenary session.

- 27 April 2007: The Fourth Tripartite Commission launched (27 April 2007–present).

Although an assessment of the commissions is difficult, it can be summarised by the shorthand label of ‘early effective, later malfunctioning’ (Kim and Bae, 2004: 117–20). The Social Compact was path-breaking, the first autonomous tripartite agreement in Korean labour history. Although this helped the government enhance its capacity for crisis management and to tackle the Crisis, the Commission did not produce any significant agreements thereafter. Therefore, while the experiments with tripartite systems were meaningful, they did not turn out entirely successful.

There are also examples at the micro level. We present here the cases of LG Electronics (LGE) and Samsung SDI.1 Both are in the electronics industry, have histories of severe labour disputes and are successful. During workplace innovations towards a high performance work organisation (HPWO), these chaebol took quite different routes and modes of HPWO. The 1997 Crisis pushed their management to make workplace innovations. Both management and employees developed more cooperative and participative employee relations. Management changed styles and attitudes from paternalistic and authoritarian towards more progressive and participative forms. Unions and employees were also effectively involved in the process of workplace innovation. Cooperation of the union leadership or employee representatives helped to establish a new work production system. While unionised LGE adopted a team production mode with a labour–management partnership, non-union Samsung SDI had a lean production mode emphasising Total Quality Management (TQM), Six Sigma and other management–initiated innovations. So, trade union status made a difference in the HPWO adoption process in terms of speed, method and persistence.

In the case of LGE, during 1990–94 labour–management cooperation remained at the affective and attitudinal level. However, at the next stage (post-1994), the partnership of labour and management changed towards a more structural and institutionalised level. In the high-tech electronics industry most competitors are non-union, such as Samsung Electronics in Korea and IBM, Motorola and HP in the United States. The initial adoption process was slow in LGE due to strong union resistance, whereas Samsung SDI more speedily adopted new approaches. While LGE used a more bottom-up approach, with the involvement of frontline employees, Samsung SDI chose a management-centred top-down approach. However, when an HPWO is established, we expect the team production mode to be more strongly institutionalised in the unionised setting, which may more likely prevent easy abandonment. Although LGE shows very active union participation in workplace (that is, lowest) and collective bargaining (that is, middle) levels, it is not practised in the strategic (that is, highest) level, such as product development, investment and restructuring. This may be a future agenda for labour. Samsung SDI operates an extensive system of open communications, information sharing and non-union employee representation. Although this has cultivated the attitudinal aspects of employee relations (that is, labour–management cooperation), its structural and institutional aspects (that is, employee participation through formal mechanisms), have not yet fully developed.

HRM Practices: Key Determinants and Review

This section has two main parts. First, there is an outline of key factors influencing HRM practices. Second, there is a review of those HRM practices.

Influences on HRM

Several key factors have influenced HRM. These include history and politics, national culture, the economy, the business environment, different institutions and globalisation.

Historical and Political Background

This North East Asian country now occupies almost 100,000 square kilometres of the Southern Korean peninsula (6,000 miles from the United Kingdom). Korea’s very homogeneous ethnic population rapidly urbanised and grew, more than doubling since the 1960s, from 20.2 million (1966) to 48.8 million (2012). Of these, nearly 10 million (more than double that of the 1960s) are in the capital, Seoul, the dominant centre for political, social, business and academic interests.

Korea’s nickname of ‘the country of the morning calm’ became increasingly obsolete with massive, speedy economic development. From the 1960s Korea was rapidly transformed from a poor, rural backwater with limited natural or energy resources, domestic markets and a legacy of colonial rule and war with dependence on US aid. Korea became one of the fastest growing economies in a rapidly expanding region. Gross domestic product (GDP) real annual growth rates of 9 per cent from the 1950s to the 1990s (with more than 11 per cent in the late 1980s) took GDP from US$1.4 billion (1953) to US$437.4 billion (1994) (Kim et al., 2000). Per capita GDP grew from US$87 (1962) to US$10,543 (1996) and gross national product (GNP) from US$3 billion (1965) to US$376.9 billion (1994). From the mid-1960s to the 1990s annual manufacturing output grew at nearly 20 per cent and exports over 25%, rising from US$320 million (1967) to US$136 billion (1997) (Kim and Rowley, 2001). Korea became a large manufacturer of a range of products from ‘ships to chips’, in both more traditional (steel, shipbuilding, cars) and newer (electrical, electronics) sectors. Employment grew and unemployment levels declined, to just 2 per cent by the mid-1990s.

How did the former ‘Hermit Kingdom’ reach this position? The ‘Three Kingdoms’ (39BC onwards) were united in the Shilla Dynasty (from 668), with the Koryo Dynasty (935 to 1392) followed by the Yi Dynasty, ended by Chosun’s annexation by Japan in 1910. The colonisation experience, along with forced introduction of the Japanese language, names and labour, inculcated strong nationalist sentiments, a central psychological impetus for the later economic dynamism (Kim, 1994: 95). While colonised, Koreans were restricted to lower organisational positions and excluded from management. Other Japanese influences came via infrastructure developments, industrial policy imitation, application of technology and techniques of operations management and Korean émigrés (Morden and Bowles, 1998). Some later HRM indicated these influences, including lifetime employment and seniority pay, although with some distinctions. For instance, employee loyalty was chiefly to individuals – owners or chief executives (Song, 1997) – with little to organisations, in contrast to Japanese organisational commitment. While limited to regular, particular male employees in large firms, normative practice extended this model (Kim and Briscoe, 1997).

After 1945 came partition, with US military control until the South’s independence government in 1948 followed by further widespread devastation with the Korean War from 1950–53. The large US military presence and continued tensions with the North remain. Furthermore, many Koreans studied the American management system, especially as the country was the destination of most overseas students. This affected managerial, business and academic outlooks, perspectives and comparisons. Korea also experienced 25 years of authoritarian and military rule until the late 1980s. Additionally, many business executives were ex-officers, while many male employees served in the military and had regular military training, while some companies maintained reserve army training units.

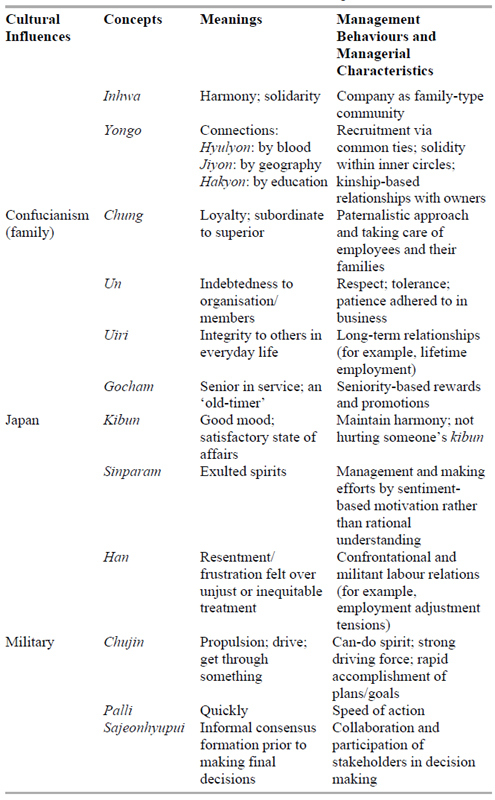

Cultural

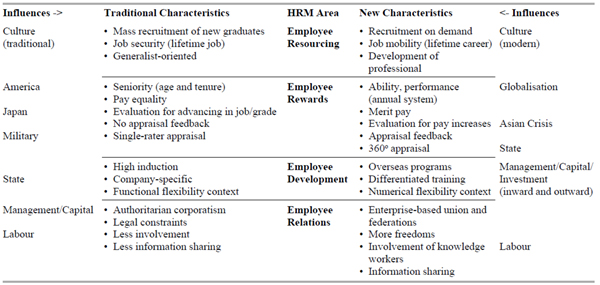

The role of national culture, including Confucianism, retains a powerful, multi-faceted and ingrained influence on Korean society in general and is embedded in HRM in particular (see Rowley and Bae, 2003; Rowley, 2013). This can be seen in summary in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1 Characteristics and Paradoxes of Culture and Management in Korea

Source: Adapted from Rowley and Bae (2003).

Economic Environment

Korea’s economic background, rapid development and the particular structure and organisation of capital and links to the state are all important to HRM’s operating context. This developmental, state-sponsored, export-orientated and labour-intensive model of industrialisation (Rowley and Bae, 1998; Rowley et al., 2002) was reinforced by exhortations and motivations (often with cultural underpinnings, as noted earlier). These included the need to escape the vicious circle of poverty, to compete with Japan, to repay debts and to elevate Korea’s image and honour.

In late 1997 the contagion of the Asian Crisis hit Korea, with devastating effects on economic performance, employment (although both quickly recovered) and in turn HRM. This was partly because the post-Crisis International Monetary Fund (IMF) ‘bailout’ loan came with stipulations of labour market changes, for instance to end lifetime employment and to allow job agencies. Furthermore, the economy opened up to greater penetration from foreign direct investment (FDI), which in turn brought exposure to HRM practices to supplement the experiences of Korea’s own multinational companies (MNCs) operating in other countries.

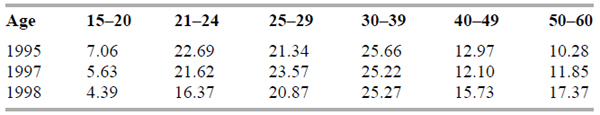

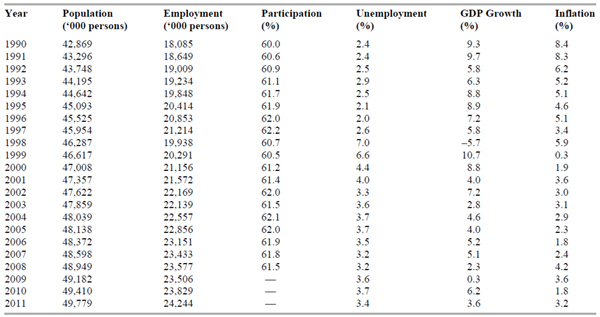

Key aspects of this economic performance and context can be seen in Tables 3.2 and 3.3. The different age and gender impacts are important to note. Basically, older and male workers remain more exposed to the vagaries and effects of unemployment, especially in a system with only a limited safety net and culturally influenced opprobrium. The situation post-1997 has been interesting. In terms of GDP there has been no real trend with large fluctuations following the massive near 11 per cent growth rate of 1999. For example, near 9 per cent in 2000, just over 7 per cent in 2002 and 6 per cent in 2010, but with lows of less than 3 per cent in 2003 and 2008 and a paltry 0.3 per cent in 2009 before bouncing back to more than 6 per cent in 2010 and falling back to more than 3 per cent in 2011. In terms of inflation, again wide fluctuations occurred, from nearly 6 per cent in 1998 to less than 1 per cent in 1999 and then 2 per cent to 3 per cent except for less than 2 per cent in 2006 and 2010 and just over 3 per cent in 2011. In terms of unemployment, this continued to decline from the 1998 peak of 7 per cent to 3 per cent to 5 per cent up to 2011.

Capital – The chaebol

These leading lights and drivers of the economy were family founded, owned and controlled large, diversified business groupings with a plethora of subsidiaries, as indicated in the label: an ‘octopus with many tentacles’. They were held together by opaque cross share-holdings, subsidies and loan guarantees with inter-chaebol distrust and rivalry. Much of the large business sector was part of a chaebol network and they exerted widespread influence over other firms, management practices and society. The chaebol were underpinned by a variety of elements (Rowley and Bae, 1998; Rowley et al., 2002) and explained by a range of theories (Oh and Park, 2002). For some, the state–military links and interactions was the most important factor, producing politico-economic organisations substituting for trust, efficiency and the market. The state-owned banks (with resultant reliance for capital), promoted chaebol as a development strategy and intervened to maintain quiescent labour. These close connections were often damned as nepotism and ‘crony capitalism’.

Table 3.2 Recent Trends in Korean Employment Patterns, Growth and Inflation

Source : Korea National Statistical Office (http://ecos.bok.or.kr).

There were more than 60 chaebol, although a few dominated. At their zenith in the 1990s the top five (Hyundai, Daewoo, Samsung, LG and SK) accounted for almost one-tenth (9 per cent) of Korea’s GDP, and the top 30 accounted for almost one-sixth (15 per cent), taking in 819 subsidiaries and affiliates. Some became major international companies in the world economy, engaged in acquisitions and investments overseas, dominated by the United States and China. A sketch of the top chaebol illustrates their typical development and structure.

Samsung is the oldest chaebol, with roots in the Cheil Sugar Manufacturing Company (1953) and Cheil Industries (1954), although it started as a trading company in 1938. It developed from a fruit and sundry goods exporter into flour milling and confectionery. Over the post-war decades it spread to sugar refining, textiles, paper, electronics, fertiliser, retailing, life insurance, hotels, construction, electronics, heavy industry, petrochemicals, shipbuilding, aerospace, bio-engineering and semiconductors. Sales of US$3 billion and staff of 45,000 (1980) ballooned to US$96 billion and 267,000 (1998) (Pucik and Lim, 2002). Samsung Electronics alone had 21 worldwide production bases, 53 sales operations in 46 countries, sales of US$16.6 billion and was one of the largest producers of dynamic random access memory semiconductors by the late 1990s. By 2002 Samsung still claimed global market leadership in 13 product categories, from deep-water drilling ships to microwaves, television tubes and microchips, and with a target to actually have 30 world beaters by 2005. In 2010 it still had 78 affiliates and assets of Won2 204,336 billion (www.kisvalue.com).

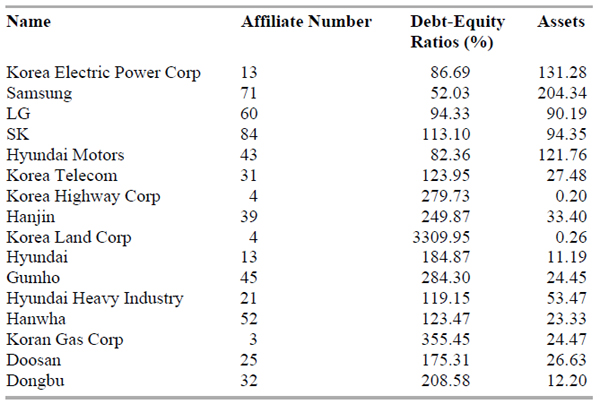

However, the Asian Crisis brought out into the open some of the inherent and underlying problems and strains that were beginning to be felt in the chaebol and in the Korean model more generally. There followed the collapse of some chaebol, scandals and bankruptcy and the reconfiguration of others, including even the takeover of some by Western MNCs. The more recent position can be seen in Tables 3.4 and 3.5 as well as later under the section on globalisation.

Labour

The critical management of labour has occurred in a variety of contexts, including military governments. Importantly, labour played an integral role against occupation and supporting democratisation. From the early 20th century low wages, hazardous conditions and anti-Japanese sentiments contributed to union formation (the following is from Kwon and O’Donnell, 2001; Rowley and Yoo, 2008; Rowley and Bae, forthcoming). From the 1920s unions increased, reaching 488 and 67,220 members (1928). The 1930s witnessed a decline with harsh repression and subordination to Japanese war production, and also internal organisational splits. Union numbers fell to 207 and 28,211 members (1935). The post-war radical union movement (the Chun Pyung) was declared illegal by the American military government trying to restrict political and industrial activities to encourage US type ‘business unions’. The subsequent strikes and General Strike resulted in 25 deaths, 11,000 imprisoned and 25,000 dismissals. A more conservative, government-sponsored industry-based movement was decreed, signalling labour’s incorporation by the state, conflict repression and an authoritarian corporatist approach. Thus, the government officially recognised the Federation of Korean Trade Unions (FKTU) and became increasingly interventionist, enacting a battery of laws regulating hours, holidays, pay and multiple and independent unions.

Table 3.4 Size and Businesses of the Largest Chaebol in Korea (‘000 billion won) 2010

Name |

Main Business |

Assets |

Samsung |

Electronics, machinery and heavy industries, chemicals, construction |

204.3 |

LG |

Clothing, supermarkets and radio, television, electronics stores |

90.2 |

SK |

Refining, distributing and transporting petroleum products, production and sale of petrochemical products |

94.4 |

Hyundai Motors |

Manufacture and distribution of motor vehicles and parts |

121.8 |

Hanjin |

Construction, shipbuilding |

33.4 |

Hyundai |

Elevators, merchant marine, finance |

11.2 |

Source: OECD in Economist (2003), www.kisvalue.com.

A diversity of approaches towards labour was also partly influenced by chaebol growth strategies (Kwon and O’Donnell, 2001). For instance, economic growth and focus on minimising labour costs resulted in the expansion and concentration of workforces in large-scale industrial estates with authoritarian and militaristic controls. The pressure and nature of the labour process was indicated in the volume of workplace accidents, some 4,570 (1987) compared to smaller numbers in larger workforces (although with sectoral impacts, of course), such as 513 in the United States and 658 in the United Kingdom (Kang and Wilkinson, 2000). Labour resistance was generated, the catalyst for conflict and re-emergence of independent unions. Employers responded by disrupting union activities, sponsoring company unions and replacing labour-intensive processes by automating, subcontracting or moving overseas. From the late 1980s companies also softened strict supervision and work intensification emphasis by widening access to paternalistic practices and welfare schemes (Kang and Wilkinson, 2000). Nevertheless, trade unionisation grew from 12.6 per cent (1970), peaking at 18.6 per cent (1989).

During the 1990s independent trade unions established their own national organisation, with federations of chaebol-based and regional associations. An alternative national federation, the KCTU (minjunochong), emerged in 1995. It organised the 1996 General Strike (Bae et al., 1997), enhancing its legitimacy. However, the economic whirlwind of the Asian Crisis then hit. Trade union density fell back to 11.5 per cent (1998).

Further details on trade union developments in Korea covering the context and history of union development as well as membership, types and structures and also collective bargaining, wages and disputes are detailed in the literature (Rowley and Yoo, 2008; Rowley and Bae, forthcoming). Similarly, the developments in the labour markets in Korea are covered in terms of the size, employment, interactions with product and financial markets and technology, the political economy as well as types of labour markets (informal, primary and secondary) and institutions in the labour market and flexibility (Rowley, Yoo and Kim, 2011).

Globalisation

Large corporations, such as Samsung Electronics Company (SEC) and LGE now have more than half of their total employees overseas. In addition, the ratio of overseas sales is more than 85 per cent. Both companies established global HRM systems in the early 2000s. In the case of SEC, it forced standardisation of HRM practices in global subsidiaries in 2004 and started to more serious implementation in 2008. LGE prepared position-based job grades at the headquarters and global integration of job categories in 2005. In 2007 they recruited chief-level foreign executives (for example, chief marketing officer [CMO] and chief human-resource officer [CHO]). Then it implemented standardisation of performance evaluation systems in 2009 and compensation policy in 2010.

Furthermore, HRM globalisation in Korean companies shifted its focus from ‘hardware’ to ‘software’. At first, companies focused on systems and practices, especially a performance-based HRM system. This hardware aspect includes performance-based compensation, position-based job grades, standardisation of performance evaluation and compensation policies (see also Yang and Rowley, 2008). The next issue was global top talent mobilisation including (re)allocation of global HRs, recruiting non-Korean executive members, decentralisation of HR directors in subsidiaries and leadership development of host country nationals. Finally, the focus of global HRM was internalisation. Some issues here include aligning different ways of doing things, vision and value sharing, and improvement of communication skills.

Review of HRM Practices

Second, a review of HRM practices is presented. First of all it is useful to compare the more traditional characteristics with newer ones in HRM and the varied influences on them, as in Table 3.6. We will then detail these categories that comprise much of HRM.

Employee Resourcing

Aspects of employee resourcing include recruitment, selection and contracts. The chaebol, traditionally seen as prestige employers, recruited graduates biannually with a preference for management trainees from prestigious universities. There have been some moves from such resourcing systems towards ongoing, atypical and insecure forms. For instance, flexibility was classified as ‘low’ numerically in pre-Crisis Korea (Bae et al., 1997). Since then flexibilities seemingly swiftly increased. The trend is indicated by a survey (of 300 firms) conducted in 1997 and 1998 (Choi and Lee, 1998). During the first period, virtually one-third (32.3 per cent) adjusted employment. By the second period this coverage almost doubled (to 60.3 per cent). For the first period, specific types of employment adjustment (firms made multiple responses) were: worker numbers (19.7 per cent), working hours (20 per cent) and functional flexibility (12.7 per cent). By the second period these types of employment adjustment massively increased: worker numbers more than doubled (43.7 per cent), while working hours (36.7 per cent) and functional flexibility (24.3 per cent) almost doubled. There was a more than doubling in both ‘freezing or reducing recruitment’, from 15 per cent to 38.7 per cent, and ‘dismissal’ from 7 per cent to 17.3 per cent, with rises in ‘early retirement’ from 5.7 per cent to 8 per cent. Thus, numerical flexibility increased. Indeed, it was argued that even by 1999 the number of temporary, contract and part-time workers comprised more than 50 per cent of the workforce (Kang and Wilkinson, 2000; Demaret, 2001). These employee resourcing areas can be seen in the growth and variety of types of non-permanent workers, as shown in Table 3.7.

In terms of more recent trends, we can see the following. For temporary workers, the percentage grew post-1995 to nearly 35 per cent but has since had steady, albeit small, declines to just less than 30 per cent by 2010. In terms of daily workers, there have been bigger changes and fluctuations, from just less than 14 per cent in 1995 to nearly 18 per cent in 1999 and about 14 per cent up to 2006 before declining to nearly 11 per cent by 2010. In terms of regular workers, the nearly 59 per cent level of 1995 declined continually to less than 50 per cent by 2002 but since increased constantly back again to nearly 60 per cent by 2010.

Table 3.7 Trends in Employment Status in Korea (%)

Regular workers |

Temporary workers |

Daily workers |

|

1995 |

58.14 |

27.89 |

13.97 |

1996 |

56.81 |

29.60 |

13.59 |

1997 |

54.33 |

31.60 |

14.07 |

1998 |

53.14 |

32.87 |

13.99 |

1999 |

48.44 |

33.60 |

17.96 |

2000 |

47.87 |

34.49 |

17.64 |

2001 |

49.16 |

34.60 |

16.24 |

2002 |

48.39 |

34.45 |

17.16 |

2003 |

50.47 |

34.74 |

14.79 |

2004 |

51.19 |

34.12 |

14.69 |

2005 |

52.14 |

33.30 |

14.57 |

2006 |

52.76 |

33.07 |

14.17 |

2007 |

53.98 |

32.39 |

13.64 |

2008 |

55.57 |

31.34 |

13.09 |

2009 |

57.07 |

31.00 |

11.93 |

2010 |

59.43 |

29.86 |

10.71 |

Source: The Statistics Korea (KOSTAT) (www.kostat.go.kr).

Another aspect of employee resourcing concerns the numbers of graduates and the attractiveness of small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The rate of increase in labour with university degrees exceeded demand. This over-supply started after the 1997 Asian Crisis when companies minimised new recruitment. It seems that there are simply not enough ‘sought-after’ chaebol jobs, as these provide only 10 per cent. While under 30 year old unemployment stands at 8.3 per cent and SMEs reported 250,000 unfilled vacancies in 2011, graduates are not attracted to SMEs due to lack of training and poor pay and welfare entitlements as well as the weak position of SMEs (Oliver and Buseong, 2012).

Some company cases also highlight employee resourcing practices. Samsung Electronics’ 60,000 employees (1997) were massively reduced by about one-third to 40,000. LG Group in 1998 dismissed 14,000 (11.6 per cent of its total) employees (Kim, 2000). Daewoo Motor shed 3,500 jobs, despite violent protests and strikes. Some 30,000 employees at public companies like Korea Telecom, Korea Electric Power Company and Korea National Tourism Organisation were to be dismissed while another 30,000 (10 per cent) of local public servants were dismissed by the end of 1998 (Park and Park, 2000).

However, there were some limits to such employee resourcing practices. At first, neither government nor chaebols seemed overly keen to use the new legislation (The Economist, 1999). This inertia can be seen in the following cases where adjustment was constrained. Korea Telecom moved towards increased adjustment via changes in job categories, transfers and promotions (Kwun and Cho, 2002). Rather than dismissal, a Samsung subsidiary asked both men and women to take unpaid ‘paternity leave’ while Kia remained ‘proud’ of its ‘no-lay-offs’ agreement and Seoul District Court protected jobs by refusing to close Jinro (The Economist, 1999). One high-profile example concerned Hyundai Motor, whose initial plan to dismiss 4,830 of its 45,000 workers was diluted to 2,678 and then 1,538. The union went on strike in 1998, followed by illegal strikes and physical conflict until a negotiated compromise was reached. This provided for just 277 dismissals (with 167 of these from the canteen!), along with severance payment. As a result, while Hyundai’s workforce fell to 35,000, this was mainly due to 7,226 voluntary retirements plus about 2,000 who will return after 18 months’ unpaid leave (The Economist, 1999). Indeed, some collective dismissals, such as the 1,500 figure at Hyundia Motor, were regarded as ‘illegal’ and ‘unreasonable’ (Lee, 2000).

Employee Rewards

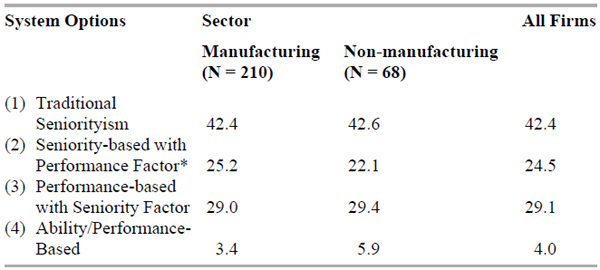

There has been some increasing importance attached to performance in employee rewards practices. Some of the reasons for this were: pay system rigidity making labour almost a quasi-fixed cost; weak individual-level motivational effects; and changing environmental factors (Kim and Park, 1997). However, there is actually more variety here than what an overly stark ‘either-or’ choice presents. Table 3.8 indicates this.

Data from the earlier survey (Choi and Lee, 1998) indicated that employee rewards flexibility almost quadrupled from about one-tenth (10.7 per cent) to nearly four-fifths (38.7 per cent) from 1997 to 1998. Table 3.8 shows that about one-third (33 per cent) of firms had performance-based – (3) or (4) – systems. There seem to be common trends across sectors, although with some greater change in use of (4) in non-manufacturing vis-à-vis manufacturing. Slightly more variation by size of organisation would be expected given that size is a powerful variable in many HRM areas. Somewhat counter-intuitively, (1) was used by slightly more ‘smaller’ (although defined at a relatively high employment level here) firms, while more than twice the percentage (although still a small total percentage) compared to ‘larger’ ones used (4).

Table 3.8 Variations in Korean Pay Systems By Size And Sector (%)

Source: Adapted from Park and Ahn (1999).

Notes: * Originally labelled ‘Ability-based system, but seniority-based operation’.

It has been noted that post-1997 pay for performance systems (‘Yunbongje’) became more rapidly adopted (Yang and Rowley, 2008). For example, going from low coverage (just 1.6 per cent of firms) in 1996 to getting on for nearly one-quarter (23 per cent) by 2000 and nearly one-half (48.4 per cent) by 2005 (Ministry of Labor, various). Key features of ‘Yunbongje’ include not only that differences in individual performance and contributions to organisational success are reflected in pay, but that many complex components (that is, base pay, various allowances and fixed bonuses) are merged and can be adopted in the form of merit pay (Yang and Rowley, 2008).

The example of annual pay, whereby salary is based on individual ability or performance, is another employee rewards practice. A survey (1999) of 4,303 business units (with more than 100 employees) found that 15.1 per cent had already adopted annual pay; 11.2 per cent were preparing for it; and 25 per cent were planning to adopt it (Korea Ministry of Labor, 1999). Thus, just over one-quarter (26.3 per cent) of firms had either introduced it, or were preparing to. Indeed, just over one-half (51.3 per cent) of firms were in some stage of changing pay systems. Again, there seemed to be common trends across organisational size.

Other evidence indicates employee rewards practices being used and considered. Some 13 per cent (more than double 1998’s 6 per cent) of companies listed on the Korean Stock Exchange were giving share options, with some 18 per cent (more than quadruple 1998’s 4 per cent) of l5,116 large companies sharing profits in January 2000, with another 23 per cent planning to do so by year end (Labor Ministry survey in The Economist, 2000).

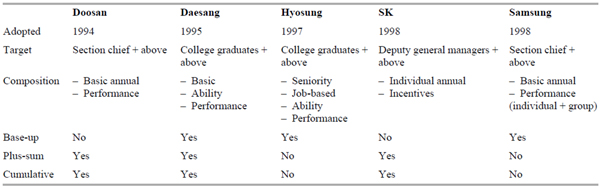

Again, we give company examples of employee rewards. The operation of annual rewards systems can also be seen in specific cases. Instances among the chaebols are shown in Table 3.9. All used forms of annual pay systems. Samsung and Hyosung adopted a ‘zero-sum’ method, reducing salary for poorer performers while increasing pay by the same amount of reduced salary for better performers. Doosan, Daeang and SK used a ‘plus-sum’ method, increasing salaries of good performers without reducing those of poor performers. Finally, some firms accumulated performance evaluation results.

In Samsung remuneration had been composed of base pay (based on seniority), plus extra benefits (long service, and so on) until it introduced its ‘New HR Policy’ (1995) with its greater emphasis on performance. Now remuneration was composed of base pay (common pay, cost-of-living), plus merit pay (competence and performance used) (Pucik and Lim, 2002; Kim and Briscoe, 1997). The LG Group introduced (in 1998) practices to determine pay based on ability and performance (Kim, 2000). LG Chemical brought in a system of performance-related pay at its Yochon plant (The Economist, 1999). Korea Telecom made some moves towards more flexibility and performance in rewards (Kwun and Cho, 2002). Hyundai Electronics introduced (in 1999) share options. SEC used profit sharing. Originally its frame was to give profit sharing based on the performance of business unit up to 50 per cent of their annual salary. Since Samsung experienced that this pay scheme generated some sense of inequity among employees, they changed the scheme by having 20 per cent of profit sharing as a common rate that applied to all employees regardless of business performance in 2007; and the commonly applied rate was increased to 40 per cent in 2010. Hence, if they have sufficient resources, now the range of profit sharing to their annual salary is 20 per cent to 50 per cent.

Table 3.9 Comparison of Annual Pay Systems Among Korean Chaebols

Source : Adapted from Yang (1999: 232).

The key lever in operationalising these employee rewards practices is performance appraisal (Yang and Rowley, 2008). Traditionally, it did not affect pay (or promotion). Given this new emphasis, however, Samsung’s appraisal system was re-vamped and made more sophisticated in the search for greater objectivity and reliability. It was now composed of several elements, such as: supervisor’s diary; 360-degree (supervisors, subordinates, customers, suppliers) appraisal; forced distribution; and two interviews (with the supervisor; ‘Day of Subordinate Development’). The ‘Evaluation of Capability Form’ used was composed of interesting items, such as ‘Human Virtues’, for example, ‘morality’: willingness to sacrifice (sic) themselves to help colleagues (Kim and Briscoe, 1997).

Again, the extent of such employee rewards practices requires some consideration. Some practices are relatively limited in coverage and spread. For instance, data in Table 3.8 also indicated that seniority remained in large numbers, more than two-fifths of firms (nearly 43 per cent). Indeed, some form of seniority – (1) or (2) – accounted for the pay systems of over two-thirds (67 per cent) of firms. Likewise, data in Table 3.9 indicated that most firms applied practices only to certain groups, such as managers or the higher educated. Some, such as Samsung, Daesang and Hyosung, used ‘base-up’ methods, a uniform increase of basic pay regardless of performance or ability levels. Similarly, Hyundai’s vaunted stock option policy covered just 7 per cent of the workforce while Samsung’s profit sharing was restricted to ‘researchers’ (The Economist, 2000). At LG, although employee evaluation systems were in place, in most instances compensation did not reflect evaluation results as it remained ‘largely determined by seniority’ (Kim, 2000: 178).

Also, there are many problems with trying to link employee rewards and performance via appraisals with distal and proximal factors, along with intervening, judgement and distortion factors (see Yang and Rowley, 2008). These concern appraisals in general, when linked to rewards and in Asian contexts (see Rowley, 2003). For instance, well-known tendencies in human nature lead towards subjective aspects in appraisals. Furthermore, practitioner-type literature commonly recommends that appraisals should not be linked with remuneration. There are also concerns that appraisals cut against the ‘professional ethos’. Finally, there are cultural biases to be aware of. For example, Korean managers are often unwilling to give too negative an evaluation, as inhwa emphasises the importance of harmony among individuals who are not equal in prestige, rank and power, while supervisors are required to care for the well-being of their subordinates and negative evaluations may undermine harmonious relations (Chen, 2000). Another Korean value, koenchanayo (‘that’s good enough’), also hampers appraisals as it encourages tolerance and appreciation of people’s efforts and not being excessively harsh in assessing sincere efforts (Chen, 2000).

Employee Development

Korea’s spectacular post-war economic growth and some chaebols have been influenced by a skilled and well-educated workforce with heavy investment in the development of HRs (Yoo and Rowley, forthcoming). It was argued that the success of companies such as Pohang Iron and Steel (the predecessor of POSCO) was due in part to its employee development and regular training (Morden and Bowles, 1998). Many espoused the Confucian emphasis on education with very strong commitment to it and also traditional respect and esteem attached to educational attainment. This is indicated by high levels of literacy, a high proportion of scientists and engineers per head of population and that 70 per cent of the workforce graduated from high school (Morden and Bowles, 1998).

Employee development can be classified (Kim and Bae, 2004) as: new recruits and existing employees; in-house and external; language proficiency, job ability, character building; and basic and advanced courses. Many chaebols put strong emphasis on training and have their own well-resourced and supported training centres. There is often many (three to six) months’ in-house induction training with new employees staying at training centres or socialisation camps. Here they are inculcated in company history, culture, business philosophy, core values and vision, to develop ‘all-purpose’ general skills through which to enhance team spirit, a ‘can-do’ spirit, adaptability and problem-solving. They use ‘sahoon’ (shared values explicitly articulated), a company song and a catchphrase to buildup feelings of belonging, loyalty and commitment (Kim and Briscoe, 1997; Kim and Bae, 2004). These centres also provide ongoing training and a variety of programmes. For instance, in 1995 Samsung spent US$260 million on training, Hyundai spent US$195 million and Daewoo and LG spent US$130 million each (Chung, Hak Chong and Ku Hyun, 1997).

Some companies use invited foreign engineers to work with them and transfer skills and some send their own trainees overseas (Kim and Bae, 2004). Managerial-level training focused more on moulding managers to the company’s core values and philosophy rather than developing their job-related abilities and knowledge. Programmes placed more emphasis on building character and developing positive attitudes than on professional competence. One popular way to improve job-related skills was job rotation and multi-skilled training, but these were not applied systematically and varied between industries (Kim and Bae, 2004). Many large firms launched several programs to promote business–university partnerships. In addition, overseas training programmes to provide opportunities have been introduced and many companies give employees with requisite qualifications or appraisal results opportunities to study at foreign universities, for example, Samsung’s ‘Region Expert’ program sends junior employees overseas for one year in order to obtain language skills and cultural familiarity (Kim and Bae, 2004).

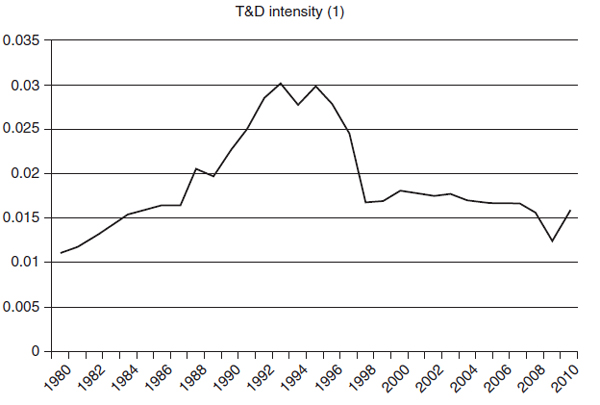

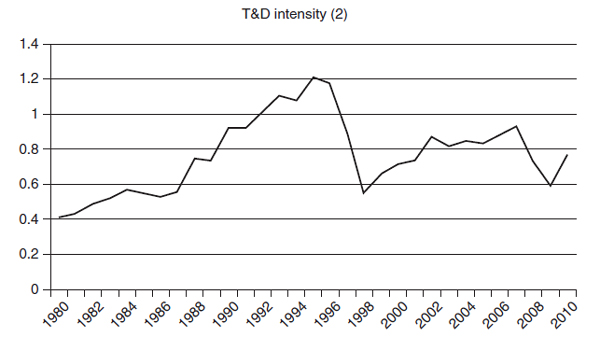

In terms of more macro data, we can note the following on training and development (T&D). This is in terms of post-1980 trends in T&D ‘intensity’ measured by labour costs and total sales.

In more detail, this table shows that after the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the level of T&D intensity by total labour cost dropped and remained constant (see Figure 3.1). It also indicated that the post-1997 situation (see Figure 3.2) looks less clear for T&D intensity by total sales as the peak was during the mid-1990s and after the Asia Financial Crisis levels recovered, but not to the previous level. Further detail on workforce developments and skills can be seen in the literature (see Yoo and Rowley, forthcoming).

Table 3.10 Level of T&D Intensity in Korea (Using Labour Cost and Total Sales): 1980–2010

Year |

T&D intensity (1) (= investment/total labour cost) |

T&D intensity (2) (= investm total sales)*1000 |

1980 |

0.0111 |

0.4112 |

1981 |

0.0118 |

0.4364 |

1982 |

0.0129 |

0.4905 |

1983 |

0.0142 |

0.5184 |

1984 |

0.0154 |

0.5720 |

1985 |

0.0160 |

0.5541 |

1986 |

0.0165 |

0.5302 |

1987 |

0.0164 |

0.5579 |

1988 |

0.0206 |

0.7476 |

1989 |

0.0197 |

0.7335 |

1990 |

0.0226 |

0.9230 |

1991 |

0.0251 |

0.9248 |

1992 |

0.0286 |

1.0207 |

1993 |

0.0302 |

1.1089 |

1994 |

0.0277 |

1.0801 |

1995 |

0.0298 |

1.2149 |

1996 |

0.0278 |

1.1788 |

1997 |

0.0245 |

0.8996 |

1998 |

0.0167 |

0.5475 |

1999 |

0.0169 |

0.6630 |

2000 |

0.0181 |

0.7169 |

2001 |

0.0179 |

0.7392 |

2002 |

0.0175 |

0.8770 |

2003 |

0.0177 |

0.8183 |

2004 |

0.0170 |

0.8502 |

2005 |

0.0167 |

0.8354 |

2006 |

0.0168 |

0.8757 |

2007 |

0.0167 |

0.9364 |

2008 |

0.0157 |

0.7242 |

2009 |

0.0123 |

0.5856 |

2010 |

0.0158 |

0.7688 |

Source: www.kisvalue.com.

Notes: Calculation based on 243 firms with external audit by law and that have survived since 1980.

Employee Relations

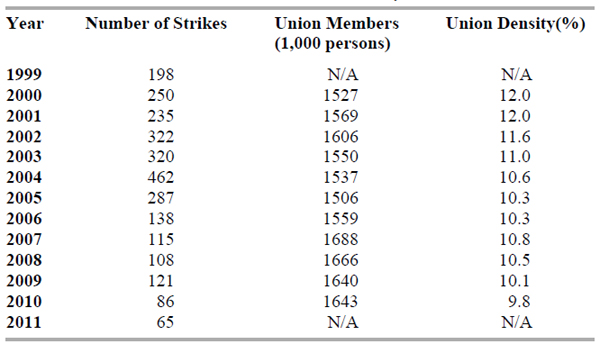

By 1998 there were 1.40 million union members (12.6 per cent density) and increasing numbers of strikes, 129; rising to 1.53 million members (12 per cent) and 250 strikes by 2000 (Kim and Bae, 2004). Thus, unions can be highly militant. Furthermore, unions are strategically well located in ship and automobile manufacture as well as power, transportation and telecommunications. Conflicts had often been high-profile, large-scale and confrontational. For example, the 1992 week-long occupation of Hyundai Motor was ended by 15,000 riot police storming the factory (Kim, 2000).

From the late 1980s the institutions, framework and policies of employee relations all reconfigured under pressures from political liberalisation and civilian governments, joining the International Labor Organization (ILO) (1991) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (1996), trade union pressure and the Asian Crisis. Nevertheless, the frames of reference and perspectives for management remain strongly unitary. In contrast, this is less so for labour, with stronger pluralist, and even radical, perspectives evident. The position of the state is more ambiguous, especially given the background of the current president and some seeming shift from the initial pluralist stance, towards a more unitary one. This can be seen in the following examples.

There were strikes by power plants and major car makers in 2002, and a week-long truck driver strike in early 2003. This latter dispute crippled Pusan, the world’s third largest port, which handles 80 per cent of Korea’s ocean-going cargo, and which risked manufacturers, such as Samsung and LG Chem, grinding to a halt by choking their supply and distribution channels (Ward, 2003). The government made concessions to resolve this dispute, which included fuel subsidies, tax cuts and lower highway tools for trucks (Ward, 2003). It was also seen as part of the new President Roh Moo-hyun’s policy of resolving labour disputes peacefully through dialogue. Similarly, the privatisation of the national railway network has been cancelled, while the sale of the state-owned Chohung Bank stalled, both amid fierce union opposition (Ward, 2003). These instances can be seen to support a more pluralist approach.

However, a more unitarist sentiment can also be detected. For instance, in 2002 there was imprisonment of unionists, refusal to recognise public sector unions and ending of the power workers’ strike after several weeks of public threats and intimidation and surrounding their Myong-dong Cathedral camp with riot and secret police. In 2003 there were high-profile disputes by truck drivers and bankers and a four-day strike of railway workers was crushed by more than 1,000 arrests. Korea is still seen as repressive, flouting trade union rights and ILO Conventions 87 and 98 by restraining the rights to freedom of association, collective bargaining and strike action. Thus, in 2002 the president of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions was imprisoned for two years for ‘obstructing business’ by simply coordinating a general strike (ICFTU, 2003).

In terms of union membership and density, as well as number of strikes, these can be seen in Table 3.11. Post-1997 the number of strikes rose to a peak of 462 in 2004 with rapid decline to just 65 by 2011. Membership grew to nearly 1.7 million by 2007 with a gentle decline, albeit still at a higher level than any years except 2007–08. Unlike trends in strikes and membership, union density has shown a consistent trend, and one going down gently from the post-1997 peak of 12 per cent to less than 10 per cent by 2010. Further details can be seen in the literature (see Rowley and Bae, forthcoming).

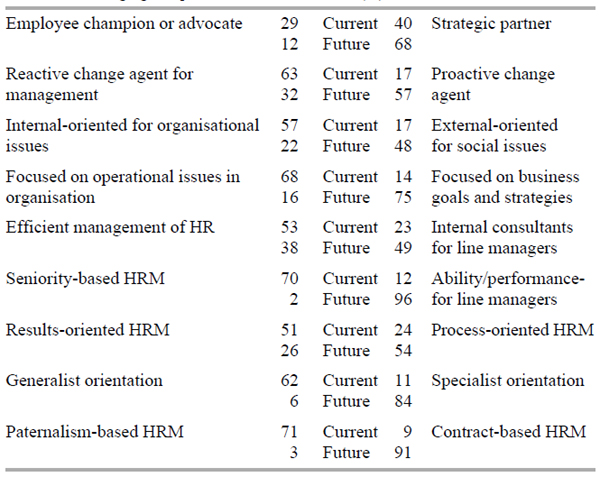

Changes Taking Place within the HR Function

Traditionally in the chaebol there were links between the HR department and the powerful chairperson’s office, which made many important HR decisions. Thus the HR function was closely tied to the highest level of the chaebol (Kim and Briscoe, 1997). More recently, HR units have changed their roles from the traditional administrative aspects towards more strategic value-adding activities. This is shown and summarised in the Table 3.12. This is based on a survey that was done by the Korea Labor Institute in 1999 of HRM professionals both in academia and practice (for example, professors of HRM, researchers in research institutes affiliated to big corporations, senior HRM consultants and HR executives of the top forty companies in Korea). A total of 140 questionnaires were distributed and 107 were returned.

The first change is in HRM organisation. Traditionally Korean firms had the perception of ‘anybody can assume HRM jobs’, meaning that HR practitioners did not need any special competencies or qualifications. This reflects a ‘lowest common denominator’ syndrome: a small fraction of HRM activities created the large proportion of value-added, whereas most activities added little value (Baron and Kreps, 1999). The shifts in this also occurred in several different ways. As aforementioned, the roles of HR professionals have changed to more strategic roles. To become business partners, HR managers started to align HRM configurations with business strategies and organisational goals. Some empirical evidence also confirms this (Bae and Lawler, 2000; Bae and Yu, 2003). In addition, firms also started to reorganise their HR units by differentiating them into several specialities and sections, that is, HR planning, recruitment, HR support team, and employee relations, and by adopting a separate shared service unit.

Table 3.11 Number of Strikes, Union Members and Density in Korea

Source: Ministry of Labor (various).

A second change in the HR function, related to the first, involves the efforts to enhance the competencies of HR professionals. Three different strategies are employed: (1) initiating various education programs for HR managers (see Kim and Bae, 2004); (2) transferring to HRM units people who have various experiences in organisations, such as planning, sales and research and development (R&D); and (3) recruiting HR professionals from outside who are trained in graduate-level programs or experienced in other organisations. All these strategies were unusual in the past.

Another change in the HR function is the outsourcing phenomenon (similar to that in some other countries such as the United Kingdm; see Rowley, 2003). Various HR activities may be outsourced. Areas highly prone to outsourcing were: education and training (by 85 per cent of respondents); outplacement (77 per cent); HR information systems (77 per cent); followed by job analysis (68 per cent); recruitment and selection (56 per cent); and then operation of salary and pay (53 per cent), as shown in Park and Yu (2001) using the same survey as that in Table 3.12.

Partly as a result of these trends, HR service firms have drastically increased (Rowley and Bae, 2003). These include outsourcing for general affairs and benefits, HR consulting, education and training, head-hunting, e-HRM and HR information system providers, outplacement, online recruiting, staffing service and HRM ASP (active server pages). The approximate gross sales for such businesses (in Won in 2002) are (Kim, 2002): HR consulting (one trillion); staffing service (one and half trillion); online recruiting (200 billion); head-hunting (100 billion); and HRM ASP (50 billion).

Fourth, the adoption of e-HRM is also an example of recent change in the HR function. By managing all employment-related data through such information systems, firms gained some benefits in terms of cost reduction and speed of operations. In particular, e-recruitment through which firms efficiently screen job candidates is actively utilised.

Fifth, there were active benchmarking activities until 2006. For example, a major electronics company spent a lot of money on benchmarking. They visited more than 50 major companies around the world such as GE, IBM, Sony, Philips and so on (Bae, forthcoming). Yet, benchmarking activities suddenly decreased. Perhaps this is because practices and systems have been well established by now with a more important matter being to make those practices function well.

Key Challenges Facing HRM

A range of key challenges are facing HRM. First, there are more macro ones stemming from the economy. These include the calls for greater transparency and openness in corporate governance issues, and the continued reorganisation of capital with chaebol restructuring, FDI and takeovers, and thus exposure to non-traditional HRM practices. HR practitioners can have a role in all of these.

There is also the challenge for HRM of an ageing workforce (Bae and Rowley, 2003). For example, in 1990 the economically active population aged 15 to 19 was 639,000; by 2010 it was down to 189,260, while over the same period those aged 40 to 54 increased from 5,616,000 to 8,879,213 (KOSIS, Korean Statistical Information Service, http://kosis.kr/eng). Of course, such trends are widespread, while the implications for Korea are stark given some of the traditional aspects of culture and society, not least its strong family basis and orientation, homogeneity and exclusiveness.

Second, there are challenges from the more micro HRM policy areas. This has several elements to it. One challenge is the so-called ‘war for talent’, that is, an attraction strategy to recruit top quality talent. Many Korean corporations actively pursued recruiting and retaining such talent. For this purpose, chaebols such as Samsung, LG, SK, Hyundai Motor, Hanwha, Doosan and Kumho, provide a fast-track system, a signing-on bonus, stock options and so on. This was not an issue earlier during the ‘Seniority-Based Relational’ HRM system. Since the 1997 Crisis, the mobility of people has increased within and across large corporations and venture firms. Corporations responded to labour market changes with multiple strategies (Kim and Bae, 2004). Firms divided employees into different groups, each with their own approach: ‘Attraction Strategy’ (that is, dashing into the war for talent) and ‘Retention Strategy’ (that is, taking measures to keep core employees) for core employees; ‘Replacement Strategy’ (that is, dismissing under-performing employees) and ‘Outplacement Strategy’ (that is, providing information and training for job switching) for poor performers; and a ‘Transactional and Outsourcing Strategy’ (that is, contrac-based, short-term approach) towards atypical workers. All of these strategies had been unfamiliar to most Korean firms.

Third, another challenge is the work–family balance issue. Many firms have adopted family-friendly policies. For example, some companies keep every Wednesday as a family day; for this they turn all lights off at 6 p.m. Yuhan-Kimberly and POSCO are good examples of these efforts.

Fourth, Korean firms encountered the big challenge of enhancing creativity. Beyond catch-up or imitation strategy, Korean firms need to initiate new products and services. Samsung adopted ‘Creation Management’. When Apple launched its iPhone, Samsung was absolutely devastated. Hence the new challenge for HRM is how to enhance individual initiatives and creativity for innovation.

Fifth, managing contingent workers is also a challenge for HRM. At first, these types of workers reduced company costs. Yet, managing these people is getting harder. There are several issues here, which include the shattering of the ‘psychological contract’, re-contracting, differentiated treatment (for example, lower pay and benefits) and disharmony with regular workers, and complicated and multiple configurations. These ‘costs’ have been seen in a range of countries, while additionally in Korea, some cultural aspects (see Table 3.1), that is, the strong perception of the equality norm and a strong union movement, makes management even more difficult. According to Korean labour law, firms that have employed contingent workers for two years need to change the status of these workers to regular workers or fire them. Many of these status-changed employees are related to job-based HRM. As mentioned earlier, job-based HRM has been somewhat diffused for cost reasons.

Finally, performance-based systems have also generated HRM challenges. In some aspects, firms gained higher productivity and performance after adoption. However, it also produced downsides too. Commonly, people only become involved in those activities that are evaluated by their organisation – the ‘no evaluation, no act’ syndrome or the dictum ‘what gets measured gets done’. Therefore, organisational citizenship behaviours, which used to be more common in Korean firms, are now more rarely observed. Another phenomenon is that people are more reluctant to cooperate with other teams or divisions. This has become even more critical since some profit-sharing programs were adopted. This is particularly problematic for electronics companies pursuing digital convergence, as this requires high levels of cooperation and coordination. Finally, people became more prone to focus on current and short-term goals, especially in R&D divisions or institutes. Researchers avert high-risk long-term projects, the critical foundation for future success.

We evaluated the institutionalisation of performance-based HRM as a half-success story in our earlier version. As mentioned previously, performance-based HRM has been challenged for the past few years. Many companies are currently trying to search for a more balanced employment relationship.

What is Likely to Happen to HR Functions?

With regards to HR units, we expect re-engineering of HRM processes and decentralisation. The shrinkage in headquarters’ HR practitioners, and increases in business division HRM, will be accelerated. Decentralisation will be realised through the transfer of HRM-related activities to line managers. Again, some activities will be accomplished by outsourcing. However, the difficulties with the necessary control, coordination and consistency in HRM, with the importance of equity and fairness within and across businesses and people in such circumstances are clear (see Rowley, 2003).

As other functional areas (for example, planning, marketing and management information systems [MIS]) have experienced, the HRM function may encounter a challenge from top management regarding the value-added by the HRM unit. HR managers in many Korean firms are currently preparing for this challenge. Following Becker, Huselid and Ulrich (2001), many firms have recently developed HR performance indexes to link HRM activities and firm performance. HRM audit and review based on the HR scorecard approach will be more actively conducted. A focus on areas such as corporate governance, ethical business practices and top executive pay, as well as managing diversity, will further allow HR to add value.

Finally, as Korean firms continue to relocate production to other countries, such as China, South East Asia and further afield, global HRM is gaining significance. Several issues here include the globalisation–localisation choice, transfer of the ‘best’ people (for example, both expatriates and inpatriates) and HR practices, and global integration and coordination. Some companies, such as Samsung Electronics, employ inpatriates from host countries to work at the head office. Other companies, like LG Electronics, send executive-level management to regional head offices (for example, China) to establish and coordinate the whole of HRM in the region. The need for HRM to have a role in this area of cross-cultural management is clear.

Case Study: The HRM Case of Doosan Heavy Industries and Construction

About the Company

Doosan Heavy Industries and Construction (hereafter Doosan HI&C) is an affiliated company of the Doosan group. The history of this firm goes back to 1962 when Hyundai Yanghaeng was founded. As part of the government’s support of heavy industries (that is, its heavy industry promotion plan), Korea’s first machinery industrial complex was established in Changwon. The name of the firm was changed to Korea Heavy Industries in 1980; and in 2001, it was privatised and renamed Doosan HI&C. Its products and services include power generation, water, castings and forgings, construction, material handling equipment, and green energy.

Doosan HI&C’s vision is to become a ‘global leader in power and water’, which reveals the determination of the firm to be a global leader in the water and power plant industries. The areas that the company wants to upgrade include proprietary technology, price competitiveness, product quality, sales volume, profitability, HR development and corporate culture. Its management philosophy includes ‘customers are our teachers’, ‘quality is our pride’, ‘innovation is our life’ and ‘people are the most important asset’. Here we focus on the company’s emphasis on the importance of people.

HRM Policies and Practices

Recruitment, performance evaluation and pay system are briefly discussed. In the case of recruitment, the company takes a 2G strategy: Growth of business and Growth of people. The company pursues business growth through the growth of people. It has four values for the selection of the right people: passion of excellence; harmony; open mindset; and professionalism. The staffing processes are very selective. The first stage is the process of screening candidates by the documents including their career history. Grade Point Average (GPA) is not considered at all, but an essay is much regarded since it provides much information regarding candidates’ values and their life story in depth. The second stage is an aptitude test using the DCAT (Doosan Competency Aptitude Test) for those who pass the first stage. Finally, the company has two interviews. The first interview is conducted by the business unit to test the competences of candidates through a structured interview and the DISE (Doosan Integrated Simulation Exercise) containing business case analysis and personal presentation. The second interview is conducted by top executives to test the values and passion of the candidates.

In the case of its evaluation and pay system, Doosan takes a strong performance-based system. Doosan was the first business group that adopted an annual pay system (a Korean-version merit pay system) in Korea. Doosan HI&C classified employees into four groups based on performance evaluation: A (10 per cent), B (20 per cent), C (60 per cent), and D (10 per cent). Then they assign average employees to the C group. This scheme is utilised for pay increases and promotions. In the case of the pay system, the company has a dual approach: a seniority-based pay grade system for blue-collar workers and an annual-based merit pay system for white-collar (office) workers. Pay differentials based on performance are cumulatively applied, which make pay differentials wide.

In addition, Doosan also adopted a job-based approach for executive members. In the past, promotion just meant a change of job title and accordingly a pay increase. However, now it means the transfer to the other job having higher job worth (see Bae 2012).

HRM-Relevant Issues

For the past 15 years the company has laid off many employees three times. First, Korea Heavy Industries (the predecessor of Doosan HI&C) laid off 340 employees in 1998 as part of an effort to privatise it. This was a measure of restructuring of the firm as many Korean firms did at that time after the 1997 Asian Crisis. However, the compulsory redundancies became a ‘signal’ of company transformation given the facts that Korea Heavy Industries was a public corporation and had strong labour union organisation. Second, during the privatisation process, about 1,000 were laid off again in 2000 to reflect decreased demand and to enhance the efficiency of the business operation. Third, in 2003 Doosan HI&C had another round of redundancies with about 1,500 employees to have a quick turnaround. These series of redundancies made possible the corporation’s new culture and ways of doing business.

Along with these redundancies, as mentioned above, Doosan HI&C adopted a performance-based pay system with strong incentive intensity. Pay differentials were wide and individual performance became much more important. These changes included an organisational culture characterised more by competition and individual performance orientation. However, the nature of the industry itself required the company to have long-term learning and knowledge accumulation, and effective collaboration and coordination. Hence there was some misfit between these two influences.

In 2007, when the plant business overseas was booming, two issues emerged. The first issue was a HR shortage since it had reduced their HR several times in order to gain efficiency. Especially, the company lacked frontline workers and lower-level managers. The second issue was HR outflow to other companies. Those who felt a sense of inequity under the strong performance-based HRM system left first. Many employees felt high pressure from pay differentials. Realising this problem, the company adopted a new direction for their HRM system towards ‘warm performance orientation’ by adopting such practices as team performance-based incentives and a common welfare system for everyone.

Useful Sources

There are a range of sources for the latest information and developments in HRM that can provide details to the reader over the years. These include the following.

Civil Service Commission: www.csc.go.kr

Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry: www.kcci.kr

Korea Labor Institute: www.kli.kr

Ministry of Education & Human Resource Development: www.moe.go.kr

Ministry of Labor: www.molab.go.kr

Ministry of Science and Technology: www.most.go.kr

National Statistical Office: www.nsohp.nso.go.kr

Samsung Economic Research Institute: www.seri.org

There is also a range of journals in the area, especially:

Asia Pacific Business Review

Asia Pacific Journal of HRs

Asia Pacific Journal of Management

International Journal of HRM

Notes

1The details of these cases are mainly from Kim and Bae (2004).

2Won = KRW. 1 KRW = 0.000540924 GBP Sterling; 1 GBP Sterling = 1,849.16 KRW (21/5/12).

References

Bae, J. (1997) ‘Beyond Seniority-based Systems: A Paradigm Shift in Korean HRM?’, Asia Pacific Business Review 3(4): 82–110.

Bae, J. (2012) Human Resource Management, 2nd edn. Seoul: Hongmoonsa (in Korean: jeok ja won non).

Bae, J. (2012) ‘Self-fulfilling processes at a global level: The evolution of HRM practices in Korea, 1987–2007’, Management Learning 43(9): 579–607.

Bae, J., and Lawler, J. (2000) ‘Organizational and HRM strategies in Korea: Impact on Firm Performance in an Emerging Economy’, Academy of Management Journal 43(3): 502–517.

Bae, J. and Rowley, C. (2001) ‘The Impact of Globalization on HRM: The Case of South Korea’, Journal of World Business 36(4): 402–428.

Bae, J. and Rowley, C. (2003) ‘Changes and Continuities in South Korean HRM’, Asia Pacific Business Review 9(4): 76–105.

Bae, J. and Yu, G. (2003) ‘HRM Configurations in Korean Venture Firms: Resource Availability, Institutional Force, and Strategic Choice Perspectives’, Working Paper, Korea University.

Bae, Johngseok, Rowley, Chris, Lawler, John and Kim, D. H. (1997) ‘Korean industrial Relations At The Crossroads: The Recent Labour Troubles’, Asia Pacific Business Review 3(3): 148–160.

Baron, J. N. and Kreps, D. M. (1999) Strategic Human Resources: Frameworks for General Managers. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Becker, B. E., Huselid, M. A. and Ulrich, D. (2001) The HR Scorecard: Linking People, Strategy, and Performance. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Chen, M. (2000) ‘Management in South Korea’, in M. Warner (ed.) Management in Asia Pacific. London: Thomson, pp. 300–311.

Choi, K. and Lee, K. (1998) Employment Adjustment in Korean Firms: Survey of 1998. Seoul: Korea Labor Institute.

Chung, Kae H., Lee, Hak Chong and Jung, Ku Hyun (1997) Korean Management: Global strategy and cultural transformation. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Demaret, L. (2001) ‘Korea: Two Speed Recovery’, Trade Union World 21(1): 21–22. Economist, The (1999) ‘A survey of the Koreas’, 10 June, pp. 1–16.

Economist, The (2000) ‘Business in South Korea’, 1 April, pp. 67–70.

Economist, The (2003) ‘No Honeymoon for Roh’, 7 June, p. 60.

ICFTU (2003) ‘Trade Union Victory in South Korea’, ICFTU Press Online, 4 March.

Kang, Y. and Wilkinson, R. (2000) ‘Workplace industrial relations in Korea For the 21st century’, in R. Wilkinson, J. Maltby and J. Lee (eds) Responding to Change: Some Key Lessons for the Future of Korea. Sheffield: University of Sheffield Management School, pp. 125–145.

Kim, K. D. (1994) ‘Confucianism and Capitalist Development in East Asia’, in L. Sklair (ed) Capitalism and Development. London: Routledge, pp. 87–106.

Kim, Y. (2000) ‘Employment Relations at a Large South Korean Firm: The LG Group’, in G. Bamber, F. Park, C. Lee, P. Ross and K. Broadbent (eds) Employment Relations in the Asia-Pacific. London: Thomson, pp. 175–193.

Kim, Y. (2002) ‘Trends in HR Service Industry in Korea’, HR Professional, 1 94–99 (in Korean: Insa service sanupeui gyunghyang).

Kim, D. and Bae, J. (2004) Employment Relations and HRM in South Korea. London: Ashgate. Kim, D., and Park, S. (1997) ‘Changing patterns of pay systems in Japan and Korea: From seniority to performance’, International Journal of Employment Studies 5(2): 117–134.

Kim, J. and Rowley, C. (2001) ‘Managerial problems in Korea: Evidence from the nationalized industries’, International Journal of Public Sector Management 14(2): 129–148.

Kim, S. and Briscoe, D. (1997) ‘Globalization and a New Human Resource Policy in Korea: Transformation to a Performance-Based HRM’, Employee Relations 19(4): 298–308.

Korea Labor Institute (2012) ‘The evaluation of employment relations of 2011 and the prospect of 2012’, Monthly Labor Review, 1: 23–32.

Korea Ministry of Labor (1999) ‘A Survey Report on Annual Pay Systems and Gain-Sharing Plans’, Korea Ministry of Labor (in Korean: Imgeumjedo siltaejosa).

Korea National Statistical Office ( ) http://ecos.bok.or.kr.

Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS) ( ) http://kosis.kr/eng.

Kwon, Seung-Ho and O’Donnell, M. (2001) The Chaebol and Labour in Korea: The development of Management Strategy in Hyundai. London: Routledge.

Kwun, S. K. and Cho, N. (2002) ‘Organizational Change and Inertia: Korea Telecom’, in C. Rowley, T. W. Sohn and J. Bae (eds) Managing Korean Businesses: Organization, Culture, Human Resources and Change. London: Cass, pp. 111–136.

Lee, C. (2000) ‘Challenges Facing Unions in South Korea’, in G. Bamber, F. Park, C. Lee, P. Ross and K. Broadbent (eds) Employment Relations in the Asia-Pacific. London: Thomson, pp. 145–158.

Ministry of Labor (various) www.moel.go.kr

Morden, T. and Bowles, D. (1998) ‘Management in South Korea: A Review’, Management Decision 36(5): 316–330.

NICE Information Service ( ) www.kisvalue.com.

Oh, I. and Park, H. J. (2002) ‘Shooting at a Moving Target: Four Theoretical Problems in Exploring the Dynamics of the Chaebol’ in C. Rowley, T.W. Sohn and J. Bae (eds) Managing Korean Businesses: Organization, Culture, Human Resources and Change, London: Cass, pp. 44–69.

Oliver, C. and Buseong, K. (2012) ‘SKorea’s Graduates Struggle in job Market’, Financial Times, 27 April, p. 5.

Park, J. and Ahn, H. (1999) The Changes and Future Direction of Korean Employment Practices. Seoul: The Korea Employers’ Federation (in Korean: Goyonggoanli byunhwawoa vision).

Park, F. and Park, Y. (2000) ‘Changing Approaches to Employee Relations in South Korea’ in G. Bamber, F. Park, C. Lee, P. Ross and K. Broadbent (eds) Employment Relations in the Asia-Pacific London: Thomson, pp. 80–100.

Park, W. and Yu, G. (2001) ‘Paradigm Shift and Changing Role of HRM in Korea: Analysis of the HRM Experts’ Opinions and its Implication’, The Korean Personnel Administration Journal 25(1): 347–369.

Pucik, V. and Lim, J.C. (2002) ‘Transforming HRM in a Korean Chaebol: A Case Study of Samsung’ in C. Rowley, T. W. Sohn and J. Bae (eds) Managing Korean Businesses: Organization, Culture, Human Resources and Change. London: Cass, pp. 137–160.

Rousseau, D. M. (1995) Psychological Contracts in Organizations: Understanding written and Unwritten Agreements. Thousand Oaks/London/New Delhi: Sage.

Rowley, C. (1998) (ed.) HRM in the ASIA Pacific Region: Convergence Questioned. London: Cass.

Rowley, C. (2003) The Management of People: HRM in Context. London: Spiro Press.

Rowley, C. (2013) ‘The Changing Nature of Management and Culture in South Korea’, in M. Warner (ed.) Managing Across Diverse Cultures. London:

Routledge, pp. 122–150. Rowley, C. and Bae, J. (1998) (eds) Korean Businesses: Internal & External Industrialization. London: Cass

Rowley, C. and Bae, J. (2003) ‘Culture & Management in South Korea’, in M. Warner (ed) Culture & Management in Asia. London: Curzon, pp. 187–209.

Rowley, C. and Bae, K. S. (forthcoming) ‘The Waves of Anti-Unionism in South Korea’, in G. Gall and T. Dundon (eds) Global Anti-Unionism. Palgrave Macmillan.

Rowley, C. and Benson, J. (2000) (eds) Globalization and Labour in the Asia Pacific Region. London: Cass.