8

Human Resource Management in Thailand

Human resource management practices in Thailand have gone through a gradual pace of learning and development. Until about the 1980s, most companies still had a so-called “traditional” personnel management (PM), which is perceived as the payroll function. Since the 1990s, the business landscape started to change. With the availability of information and communications technology (ICTs), modern human resource management practices have been more adopted in business firms. Outsourcing practices have also been widely adopted by firms to reduce their cost of operations and have led to changes in HRM business. Such practices require more partnership of HRM with other business functions. In this chapter, we will first briefly describe the historical development of HRM in Thailand. Then, we discuss the role and importance of the HR business partnership with other business functions. We review some HR practices in firms and identify some key factors that determine such HRM practices. Following this, some key changes in the HR function and key challenges facing HRM in Thailand will be outlined. Finally, a short case study is provided and details of relevant websites are given.

Development of the HRM Concept in Thailand: A Historical Perspective

The influences of military-dominated regimes, the cultural values, the centrality of Buddhism to the Thai culture and the practices of “middle-path” in Thailand (Siengthai, 1993; Lawler and Siengthai, 1997) led to a unique pattern of HRM and development practices for more than 60 years since the country first embarked on its economic development. The cultural values that emphasize power distance are reflected in much of the hierarchy between employer and employees or between supervisor and subordinates. Such value is more significantly observed in the public sector organizations in Thailand.

There are four main sectors in Thailand that exhibit distinctive characteristics in management practices and philosophy. These are the public sector, the public-enterprise sectors, the private business indigenous sector and the foreign direct investment (FDI) sector (Lawler and Siengthai, 1997; Lawler, Siengthai and Atmiyananda, 1997). The public enterprise sector is categorized as a separate sector since it has experienced significant changes in recent years in its management system. In fact, it has adopted many modern concepts of management as well as more advanced technology to improve its performance. The use of human resources in these sectors changes over time along with more available advanced technology and quality of human capital, which is enhanced by the public education system and its compulsory education requirements. At the early stage of economic development, due to the government-led economic growth, the public and state-owned enterprise sectors played a significant role in employment generation especially for the abundant supply of cheap unskilled and semi-skilled labor (Siengthai and Bechter, 2004). They have also become more or less an outlet for the capable high government ranking officials or politicians from the dominant parties who were appointed as administrators and members of the state-owned enterprise board of advisors. This practice by the governments in the past had made the public-enterprise organizations vulnerable to slow growth and internal fragmentation and political-related conflicts among key group employees. Although the number of public enterprises has been reduced mainly through government privatization policies, the concept of public management as opposed to traditional public administration has not been realized. However, together with the regionalization and globalization movements, organizational change and development has become the main focus of these public enterprises, especially after the financial crisis that forced the Thai government to effectively implement the privatization program in spite of the strong resistance from these state-owned enterprise labor unions.

In the early stage of industrialization in Thailand, the manufacturing activities were mainly labor-intensive types and their workforces were largely unorganized. The economic development was monitored through the national five-year socio-economic development plan that was started in 1961. Most of the industrial activities, apart from the agricultural activities that are the mainstream of Thailand’s economy, were mainly involved with basic infrastructure building in the country. Not until foreign direct investment started to flow into the country did modern management become the more common practice.

In Thailand, during the industrialization movement period (about the 1960s to the 1970s) and then during the significant political changes from a military-dominant to a democratic system in 1975, the threat by the unions was very significant. During 1973–75, there were many workers’ strikes; unionization was their strategy to demand change in their terms and conditions of employment (Siengthai and Bechter, 2004). The impact of the unions using industrial weapons such as strikes led to the necessity for a firm to have a formal personnel manager as well as a personnel department within the organization. The labor movement in Thailand was very strong in the public enterprise sector. Many public enterprise unions have been very well established under the Public Enterprise Labor Relations Act 1991. However, in 1990, this act was demolished. Hence, all the public enterprise unions became regulated under the general Labor Relations Act 1975, just like any other labor unions in the private sector. In 1990, the Social Security Act was passed. But it took some years for the administration of the Social Security Act to cover all types of employment insurance, such as sickness, accidents out of the workplace, being handicapped due to accidents in the workplace, old age (retirement) insurance and maternity leave and unemployment insurance.

By the time that the Labor Relations Act 1975 was issued, there were already many professionals practicing HRM. The role of these professionals and the personnel department highlighted their contribution in reducing work stoppages in the work-place and to making sure that the companies complied with labor law. Their contributions during the 1980s included keeping track of the payroll. After the financial crisis, many public enterprises came under the privatization scheme, which required organizational restructuring. So the unions’ role in the organizations has become somewhat weak. On the contrary, the role of the human resource management practices becomes more significant in facilitating such organizational changes.

Progression in HRM initiatives accelerated after the 1997 collapse of Asian financial markets. Since then large Thai organizations and particularly some small-and medium-sized financial institutions have considerably developed their HR systems (Siengthai and Bechter, 2004; Siengthai, Dechawatanapaisal and Wailerdsak, 2009). In mid-1997, when Thailand was impacted by the financial crisis, many companies had to restructure and downsize. Consequently, layoffs were experienced by many firms that had been financially involved in international markets either through exporting their products, investing overseas or even making loans from international sources through the Bangkok International Banking Facilities office. Financial insecurity and soaring inflation from the financial crisis reinvigorated the reform initiatives (of earlier periods) in many family businesses (Suehiro and Wailerdsak, 2004; Pinprayong and Siengthai, 2011). In particular, the establishments in the financial and banking sectors, owned by many of the Chinese descents’ families, had to relinquish their control in such businesses. Many were compelled to engage professional managers and/or entertain foreign direct investment or equity so that their businesses could be restructured, streamlined and recapitalized. More professional management concepts and frameworks were implemented. For instance, after the financial crisis, when many of these family-owned enterprises entered the securities market and became public companies, business practices were adjusted to improve transparency and to achieve greater efficiency. In this “era of change,” greater professionalism of HRM is expected to support marketization of various public enterprises, worker participation, welfare benefits and better job security. Some business organizations have changed the nomenclature of their human resource department to that of the “resourcing department.” Thus, the traditional concepts of personnel management and HRM have been adjusted to a broader perspective. Such action is in line with the concept of the resource-based view of an organization that advocates that an entity will gain a greater competitive advantage through the development and sustainability of its renewable and inimitable human resources.

HRM as a Business Partner

In this section we will discuss the changes in the role and functions of HRM and its transformation into the HRM business partnership. The ways in which enterprises are managed to achieve organizational goals are affected by the globalization process. The latter brings many rapid changes into the competitive environment, especially changes that have been brought about by the advancement in the new information and communications technology environment. These rapid economic changes have led to the notion of the HR system as a strategic asset (Amit and Shoemaker, 1993). This ideal is delineated by Becker, Huselid and Ulrich (2001) who asserted that the development of HRM practices can be represented by four evolutionary processes. These processes are identified as (1) the personnel perspective, (2) the compensation perspective, (3) the alignment perspective, and (4) the high-performance perspective. Interestingly, these authors claim that the compensation perspective is revealed in firms that use bonuses, incentive pay and meaningful distinctions in pay to reward high and low performers. Meanwhile, the high-performance perspective is experienced when senior executives of firms view HR as a system embedded within the larger system of the firm’s strategy implementation. This is when HRM becomes a full-fledged business partner to other functional areas of firm business. The notion evolves from a concentration on employee welfare to one of managing people for the best possible productivity of the employee. In Thailand we can say that due to the earlier strong labor movement in the public enterprise sector, the pressure from the globalization process, the fiercer competition in the market and rapid changes that are taking place in the business sectors, the HRM division of these organizations have become more active as a partner for change implementation. They have to become more strategic in their orientation and align their business plans to the strategic direction of firms. However, this change in HRM orientation is taking place more evidently in larger firms and particularly those playing in the global markets.

Key Factors Determining HRM Practices

There are many factors that determine HRM practices in any country. In this section we will describe and discuss some of the key factors that are found to have influences on HRM practices in Thailand. These include external factors such as economic and socio-political development, and internal factors such as management development, ownership, cultural values—both national and corporate values, technological innovation availability, organizational restructuring and development of an industrial relations system.

Economic and Socio-political Developments in Thailand

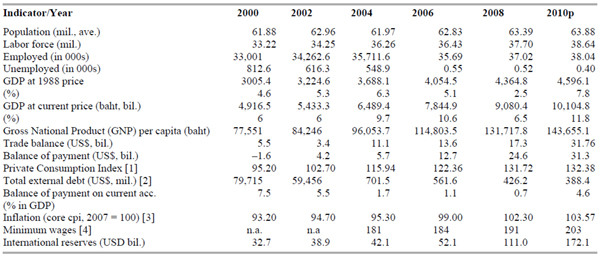

The economic and social development in Thailand became the formal mission of each government since 1961 when the first National Economic Development Plan was formulated. However, the HRs or social development concern did not come into consideration until the Third Plan (1973–78) when the notion was incorporated into the national planning and was recognized as the National Economic and Social Development Plan. The Thai economy experienced the peak and trough of its economic development from late 1980 to 2010. It made a sharp turn with a rapid growth during 1986–97. Then, the Asian Financial Crisis led to the collapse of the economy. After some years, Thailand could achieve a fast resilience of the economic growth. Table 8.1 shows that during 2000–10, the population growth of Thailand seems to be growing at a decreasing rate. But the labor force has been increasing steadily, that is, from 33.22 million in 2000 to 38.04 million in 2010. Notable is the drastic low level of unemployment after 2004. It was almost a full-employment situation in Thailand. Wage levels are reflected in the minimum wages in each region of Thailand, which are also rising reflecting the higher ability of the employer to pay. In addition, there has been fewer strikes and lockouts in recent years. Private consumption is increasing gradually, which should induce more investment for production and services. In general, the external debt of the country is reducing. Trade balance is positive, which suggests that Thailand was exporting more than importing goods and services. Gross domestic product (GDP) dropped sharply in 2008 but then increased significantly again in 2010. However, the country experienced some setbacks due to the “Hamburger crisis” when global trade collapsed following Lehman’s failure in September 2008. This collapse has profound consequences for Thailand where exports account for over 60 percent of GDP. The country then experienced the political turmoil in 2010. In spite of all these profound shocks, the Thai economy seems to perform sufficiently well and stood the severe tests (IMF, 2010).

The government has been one of the key drivers for the economic growth in the country. They are the player, the rule-maker and the referee in the socio-economic development process particularly in terms of employment practices, fair labor standards and the labor movement. In Thailand, the labor movement has been very strong in the public enterprise sector, reflected in the high level of membership (Siengthai et al., 2010). About two-thirds of union members work for public enterprises, with a union density rate of about 60 percent. However, with the government policy to deregulate and privatize by 2006, agreed in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) forum, the union has become low profile and inactive in some cases. On the other hand, the HRM divisions of these organizations have become more active as a partner for change management. To a large extent, the change has somewhat reduced the strengths of the labor union movement as the human resource management practices become more like those of the private business sector, which in general life-time employment or the seniority system as practiced in the public sector is no longer observed. In the same year, however, the Social Security Act was passed but without the unemployment insurance, which only became effective much later. Thus, the influence of the government, as a socio-political factor in HRM and IR practices, has also been significant in its legal initiatives.

Management Development and the HRM/IR Interface

With the establishment of industrial estates in many provinces in the country to promote foreign investment, the demand for managerial skills has increased. This has led to the transfer of management knowledge among member firms in the MNC networks as well as among firms within certain industrial estates. The personnel management function played a significant role in reducing the interruption in the manufacturing process of the firms in question. Personnel managers, particularly the experienced ones, were highly sought after and hence the knowledge and know-how transfer among firms. Various management development programs became more available and widespread, especially those offered by higher education institutes. The fact that managerial employees are developed leads to low level of conflicts between labor and management. So did the possibilities of effective union avoidance strategies.

Table 8.1 Thailand’s Economy at a Glance

Source: Bank of Thailand.

p = preliminary

[1] PCI series are rebased according to the Ministry of Commerce (MOC) import prices index and hence data from 2000 onwards are disseminated.

[2] Exclude Bank of Thailand and Financial Institutions Development Fund’s Debt.

[3] Exclude raw food and energy items from the consumer price index basket.

[4] For Bangkok Metropolis area.

Ownership and its Impact on HRM Practices

It was not until foreign direct investment started to flow into the country in about the mid-1970s that modern, or professional, management became commonly practiced. This transition of traditional to modern management was reflected by the fact that foreign, or joint venture, firms recruited managers with formal training in HRM and those who were previously expatriates sent from the headquarters to operate their HR businesses. Notably, the introduction of professional HRM practices was underpinned by managers who were educated in the foreign countries, particularly in the home countries of the multinational enterprises (MNEs), or the joint venture companies (Siengthai and Bechter 2004). Different nationality or ownership of firms may then have significant impact on HRM practices and organizational performance. In Thailand, during the first wave of foreign direct investment, the competition for skilled human resources tended to be among the four main nationalities: American, European, Japanese and Thai. The latter naturally tended to be the least attractive for the job-seekers since they are least competitive in the job market with respect to pay and fringe benefits, except for very large Thai domestic firms such as Siam Cement Company, Siam Commercial Bank, Krungthai Bank and public-enterprises such as the Telecoms Authority of Thailand (TOT) and the Communications Authority of Thailand (CAT). In fact, in the 2000s, after the Asian Financial Crisis, many of the Thai large public firms also have been transformed to some extent. Many of them had entered into some joint-ventures with foreign firms. So, it is basically those small and medium firms that still retain their being Thai wholly-owned. Through this process of organizational transformation under the globalization process, it can be expected that the HRM practices become more diffused and modernized.

Cultural Influences on HRM Practices

The central notion of Buddhism, the national religion, to the Thai culture, the practices of “middle path,” which means no encouragement of extremism, has contributed to the unique HRM and industrial relations framework of Thailand (Siengthai, 1993).

Some of the Thai cultural norms that are now well recognized among expatriates include the following: krengjai (being considerate); bunkhun (reciprocity of goodness; exchange of favors; jai yen yen (take-it-easy); mai pen rai (never mind); sanuk (fun); and nam-jai (being thoughtful, generous and kind combined) (Siengthai and Vadhanasindhu, 1991). Certainly, these norms are social values emphasizing harmonious social relations and consideration for others (Kamoche, 2000). They tend to reinforce the hierarchical structure (patron–client system) in the society as well as in the workplace. Currently, most of the entrepreneurial firms are started up by the second or third generation of founders. With the new ICTs environment, they now adopt more of the modern HRM practices. Yet, we cannot expect that the HRM practices will be more pro-active or systematic when compared to the former generation or those of the more developed and large-sized family enterprises where professional staffs are more prevalent. As most of them are small, constraints of available resources are still experienced by these new generation entrepreneurs. In Thailand, in the Buddhist context, the development of human resource management is embedded in family values reflected in compassion and kindness. One of the many principles of management taught in Buddhism is known as “Brahmvihaara 4.” This principle advances a notion that those who are the leaders of others, either in the household or in the workplace, should practice four central tenets. These are (1) Met-taa (compassion), (2) Garunaa (kindness), (3) Mudhitaa (Sharing the joy of success of others), and (4) Ubekkhaa (Let go and accept that it is up to the other person’s karma when one cannot be of any further help to others even when you have already tried very hard to be so) (Siengthai and Bechter 2004). Undoubtedly, they also are dealing with more knowledgeable workers or employees (Kamoche, 2000). Thus, this affects much of their styles of leadership and people management. More specifically, HR initiatives include a more realistic commitment to training and career development, providing meaningful feedback on a timely basis, formalizing practices that currently rely too heavily on subjective criteria and balancing the need to “control” with the need to “develop.”

Technological Innovation Availability

With the availability of the information and communication technologies, firms can now be more responsive to their customers through these technologies, which enhance better communication between the producers of goods and services and their customers. New job roles such as call center operators are created and in some cases outsourced. These lead to some changes in how firms manage and measure their employee performance. In the HRM function, electronic-HRM (e-HRM) also has been introduced in various large companies in Thailand, such as Thai Airways Public Co. Ltd, TRUE, Michelin, and Hong Kong Shanghai Bank Co. Ltd. E-HRM has become more important for organizations as it enhances the efficiency in HR practices. In some other cases, outsourcing of some HR functions is adopted. The primary reason for outsourcing is to reduce capital expenditure over a business process. But HR-outsourcing does not suit the organization that functions under many changing and flexible conditions. However, the trends of HR-outsourcing will increase because the service providers in the market are increasingly providing better quality at a reasonably lower price, which results in a reduced workload for HR staff.

Organizational Restructuring

There have been changes in the structure of many organizations in the recent past. Large organizations in the service sectors, such as banks and particularly some small- and medium-sized banks, had earlier developed their HR systems in a similar way to the government bureaucratic system (Lawler and Siengthai, 1997). Today, many large organizations have restructured and implemented the business process re-engineering to cope with the fierce competition that comes with the ICTs (Pinprayong and Siengthai, 2011). These changes have been implemented to improve the efficiency and reduce the costs of operation. Organizations have attempted to become flatter. Hence the notions of empowerment and broad banding in compensation management have also been observed in recent years. (The broad banding in compensation management has resulted from the fact that many business organizations such as banks have downsized or restructured and many job position classifications were merged into a broad band of jobs that require similar skills, knowledge and abilities.) The changes in organizational structure also lead to the need for multi-skilled employees to avoid workforce redundancy.

Development of the IR System

Before 1975, workers’ associations had already been established. However, trade unions have only been legalized since 1975, and strikes have only been made legal since 1981. The trade union movement has been weak, both in coverage and in workplace industrial relations. Most unions are recognized at the enterprise level (Siengthai, 1999). Union membership has not been growing extensively and rapidly; in fact, it has been declining due to the globalization process and outsourcing practices. In 2011, there have been demands from the unions to the government to make the subcontracting work illegal, as it does not provide job security for workers.

In short, key factors that determine HRM practices in Thailand include economic and socio-political factors, development of the IR system, ownership, management development, technological development, organizational restructuring and cultural values. In other words, the changes in HRM practices in Thailand have been more driven by external factors rather than representing pro-active development internally.

Key Changes in the HR Function

Based on the changes in the factors discussed above, changes in the HR function can be observed in many aspects. Many leading firms are now forced to become leaner and to bring more technology and its software to applications in their business operations. Business sustainability has become one of the main goals. Firms now are moving towards an electronic-HRM system or towards outsourcing some of their HRM processes. The practices of shared services have become more common among large firms.

While e-HRM helps the company to develop the business process, it needs high investment in system development and it also reduces the personal touch between employees and the HR team. Many problems that organizations experienced with the systems are due to inadequate investment in ongoing training for involved personnel, including those implementing and testing changes, as well as a lack of corporate policy protecting the integrity of the data in the systems and its use. Softwares are often seen as being rigid and difficult to adapt to the specific work-flow and business process of some companies.

Key Challenges Facing HRM

Many challenges are brought about to the HRM function by the globalization process. At the regional level, the ASEAN integration initiatives are taking place and expected to be effective in 2015. We would expect the integration in product, labor and financial markets. Thus, many changes in the external environment created both challenges and opportunities for firms in general and for firms’ HRM in particular. In terms of labor markets development, Thailand is experiencing more advanced economic development. Thus it is expected that there will be more labor migration with respect to both the unskilled and the skilled and professional workers within the region. How firms can capture opportunities while the labor law still presents limitations with respect to work permits and non-discrimination employment practices is still a great challenge. It needs to be considered how diversity can be enhanced when most of the Thai workforce is not fluent in English and when the foreign workers may not be able to communicate in Thai. Differences in religious practices will need to be taken into account and mutually respected in order to allow diversity. The HRM function must be more pro-active and needs to take initiatives in this new role as a business partner. Among these challenges are still the deregulation policy or privatization scheme by the government, the restructuring or downsizing policies of firms, the advantage of the new ICTs and firm policies to exploit it, the shift from low-wage to high-wage and high-skilled labor as well as the need for management development to cope with these changes, the need to link between the HRM and the financial performance of the companies, organizational innovation and productivity improvement, the empowerment of employees, projec-based contracts, the management or work-force redundancy, the bipartite labor-management relations, and so on.

The current government, led by the first female prime minister, has put forward that the minimum wages will be increased up to 300 baht/day. This suggests the higher purchasing level and ability to pay on the part of the employer. The full implementation of this wage policy will, however, take some time since the small- and medium-sized enterprises will need time to adjust their pay system. It is expected that such policy will encourage firms to introduce higher labor-saving technology and to invest more on training for their existing employees. This implies that the HR division of the firm will need to plan for HRD activities to further improve the competencies of its employees to cope with technological changes.

Together with the fierce competitive environment, it is observed that in recent years there have been serious attempts by firms to retain their talents. At the same time, it is foreseen that organizations will have to keep on shredding the redundant workforce that has resulted from bringing in more labor-saving technology such as IT and from the automation of certain service functions in the organization. Thus, it is expected that employees of the older generation who are less equipped with technological skills will likely be dismissed through early retirement programs or will be laid off. This is because even though the introduction of such technology will create the need for some certain skilled labor, the workforce needed would not be equivalent to the earlier period of economic development. The other implication of this is the increase in overhead costs as higher-skilled employees will imply higher wages and salaries, hence, the need for organizational restructuring to become flatter and for large corporations to continue to enhance customer responsiveness. For those now moving into more high-tech-led operations, the new competitive landscape will necessitate that they resort to more of the individualized terms and conditions of employment for higher-skilled and scarce employees.

Based on the discussion above, it can be said that the HRM functions that are very important to facilitate changes in the organizations in conditions of fierce competition are performance appraisal and training and development. Firms need to improve their performance management system if they want to sustain their business.

Future of HRM in Thailand

It is likely that the HR functions of firms in Thailand will become more focused on performance management. As firms will pay more attention to the business plan and strategies, they will formalize their human resource management practices. The practices of strategic human resource management are expected to be in place for larger firms. More objective performance management will be implemented. With the rapid change in global markets, firms that are engaged in production and export activities will tend to resort to outsourcing activities and transform parts of their human resource management to e-HRM. At the same time, because of the climate change that has become a more serious concern of the community, firms are expected to demonstrate more of their corporate social responsibility especially with respect to environmental and labor management. To survive and sustain their business, firms will need to continuously green their people to be more conscious of the environmental concern. Thus, this movement of greening the HRM process also would eventually transform the conventional HRM into e-HRM for many of its business processes to fit with the business strategies.

In the public sector, currently, the life-time employment system that entitles the former “civil servants” has been changed to a “public sector employee” system. Therefore, those who were recruited to the public sector are not entitled nowadays to many of the benefits that the former generation “civil servants” enjoy. The ironic situation is that although the salary of the public sector employees is higher than that of the “civil servants,” it is lower than those who work in the private sector proper. In fact, the transformation of the traditional public sector system into its current form was meant to allow many public sector organizations to be able to recruit and select their own employees based on their own organizational needs and revenues without having to go through the House of Senate and public hearing processes. In reality, this transformation has not yet brought about the expected full benefits. There are no public sector unions to protect the rights and benefits of the public sector employees. No collective bargaining rights are stipulated by existing labor law. Thus, if there is no change in labor law, this situation would call for a very strong and effective leadership to assure the effective performance of the public sector organizations.

Similarly, significant changes are expected for the public-enterprise sector since the government has been deregulating. Their operating environment became fiercer since new investors: foreign and domestic alike come into the scenario. To sustain their business, the public-enterprise organizations must improve their efficiency and effectiveness. However, coupled with the political intervention, it seems to be very difficult for them to improve in terms of creativity, innovation and productivity since their employees are observed to be losing their morale. Again, this suggests that these public sector organizations need a very strong and effective leadership to breakthrough the organizational politics.

Case Study: PTT Exploration and Production Public Company Ltd

PTT Exploration and Production Public Company Limited or PTTEP is a national petroleum exploration and production company established since 1985, with Petroleum Authority of Thailand (PTT) Public Co. Ltd as a major shareholder. It is a top-10 publicly listed company in the Stock Exchange of Thailand, which operates more than 40 projects around the world and has a workforce of more than 3,000. PTTEP human resources can be classified into two main categories: the technical staffs (core competencies) such as engineers and geologists; and non-technical staffs, such as administrators and accountants. About 50 percent of the employees in the PTTEP are in generation X whose age group ranges from 30 to 44 years. More than 30 percent are in generation Y, that is, those aged less than 30. The minorities are those over 45 years of age or the baby boomer generation. It is predicted that in the year 2020, almost 100 percent of all engineers (the core competencies) will be those in generations X and Y. With the disappearance of the baby boomer, the experience and knowledge will also be vanished along with them. To overcome this issue, the top management and the HR department are focusing on developing a succession plan.

PTTEP Human Resource Management Practices

In recent years, PTTEP’s HR has become a partner with various other departments and treated them as their customers. Each department looks at HR as their business partner, a recruitment agency, assisting in finding the best candidates for vacant positions. With HR line partners, each serving different departments, the recruitment becomes faster and more effective since the HR can focus on the department that they are serving. Its recruitment system can be separated into two channels, namely, PTTEP’s own HR department and PTTEP’s subsidiary, called PTTEP Services Company. Since PTTEP is an oil- and gas-related company, the human resources essential for the company business are engineers, geologists and geophysicists. Therefore, the PTTEP HR department is responsible for recruiting core competency human power while the PTTEP Services Company is established as a recruitment agency to recruit supporting and administrative positions such as administrators, secretaries, expat staffs or technical staffs for short-term projects. PTTEP and PTTEP Services have adopted several methods of recruitment. These include referrals, a company website, a recruitment agency, campus recruitment, conferences and exhibitions.

Training and Development

Training and development are given high priority in PTTEP since the company values their employees as one of the valuable assets of the company. PTTEP pays high attention to safety, so basic training such as fire fighting and first aids are mandatory for all employees. Many other training programs, concerned with both soft and technical skills, which may be in-house or may be outsourced, are also encouraged. Employees are required to fill out their training needs every year when conducting performance appraisals. Their supervisors are also responsible for suggesting the training courses they believe their subordinates could benefit from. PTTEP invests a great deal in training. Overseas courses and conferences are nonetheless encouraged.

PTTEP has developed an “Accelerated Development Program” or “ADP” for newly recruited young engineers. This is a six to seven months’ onthe-job training program. The engineers are assigned to work for different assets (such as Arthit or Bongkot project site assets) and are relocated once they finish their terms. This program is designed to expose young engineers to different engineering disciplines. As a result, they gain a wider first-hand knowledge and experience in a short period of time. With each assignment completion, the engineers are evaluated by the project site manager. At the end of the ADP, engineers, HR staffs and related managers sit together to assess the engineers’ performances in order to identify the most suitable placement. This program also leads to better job satisfaction and a high retention rate, since engineers have had experience in various disciplines and different teams so they are able to make decisions based on their best interest. From the managers’ point of view, they are able to match engineers with the jobs according to their performance. In terms of development, PTTEP provides both domestic and overseas scholarship for its own employees. In order to reserve and share the employees’ knowledge within the company, PTTEP has formed a Knowledge Management (KM) team, which is divided into sub-teams according to job family. There are also teams set up to capture knowledge from the world’s oil and gas conferences. Knowledge-sharing sessions are also organized regularly.

Employees’ career path at PTTEP is taken into high consideration. Rotations of staffs usually occur once every two years. Job rotation and overseas assignments are means of exposing employees to various job disciplines and broadening their experiences. For technical staffs there are two main paths. One is to acquire knowledge and experience from a variety of technical disciplines or broad branding; their skills will be broad but generalized. They will be provided opportunities to expand their knowledge to management skills and will be moved towards management directions. The other is to acquire specific knowledge and experience to become technical expert in that area.

Performance Evaluation

Employee performance appraisal is conducted on an annual basis. At the beginning of the year, employees are required to complete their own Performance Development Appraisal (PDA) form according to their agreed key performance indicators (KPIs) with the supervisors. At the year end, staffs are required to evaluate themselves and supervisors are to evaluate their subordinates. The score is used to determine salary, bonus and promotion as well as a further competency development plan.

Compensation and Benefits

PTTEP is one of the companies known to provide outstanding compensation for its employees, which results in a high retention rate. The salary rate ranks top 10 in the country. PTTEP benchmark the remuneration packages with other oil and gas companies in Thailand and constantly survey the job market to ensure that the packages are equivalent to the rival companies. Basic benefits include health insurance, life insurance, provident funds, bonuses, loans and an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP). Other higher level benefits include cars with drivers for manager level up and subsidized education fees for the children of employees. For those assigned to work overseas, the remuneration packages are based on the cost of living in the countries to which they are assigned. The overseas package also includes housing, cars and three return tickets to Thailand annually. PTTEP has a welfare committee established to promote a good relationship between employer and employee for the benefits of both parties.

Conclusion

This chapter has provided the historical development of HRM, IR and personnel management in Thailand. It discusses the changes in the role and the significance of HRM from a payroll function to a business partner in the business operations in the country that is still struggling to achieve a sustainable economic development. The empirical evidence suggests that, currently, although the role of HRM practices has become more highlighted as contributing to achieve a competitive advantage of the firms, the top management perception of this function as a business partner is still not very positive, as most of the survey respondents suggest. Following this, the key factors influencing the HRM practices in Thailand are identified. The author then offers her observations of the challenges ahead to be faced by HRM and also provides the readers with some websites where information on HRM practices and development in Thailand may be accessed for future reference.

Epilogue

At the time that the chapter was prepared in October 2011 Thailand was experiencing an overwhelming natural disaster due to floods. Over half of the country’s land areas were inundated and a large number of firms had to shut down and let the floods take over after fighting without success. This irregular phenomenon no doubt would have some impact on the current human resources management practices in Thailand. It was expected that more than 300,000 employees would be without jobs for at least six months as the positions vacant in other areas where business firms operate would not be able to absorb the entire affected workforce immediately.

This was a tragic phenomenon. Just a few days before that some of the major labor unions in electronics and electrical equipment had organized a meeting with another 120 labor unions. They had come to the conclusion that they would submit a demand to the government for the following: 1) the minimum wage increase to 300 baht must be in effect in January 2012 and applicable to all provinces in Thailand to ensure justice; 2) all the contract employment that had its nature being insecure must be abolished; 3) the government must control the inflation rate.

It is our view that we may expect in the future more of the uncontrollable consequences of climate change such as global warming and natural disasters in spite of all the human-made efforts. Thus, in the short term, the role of human resource management in Thailand based on the Buddhist-related values will be paying attention to the welfare of employees (reflecting the compassion of the management) while trying to improve the firm performance management to increase the productivity of employees (reflecting competency-based performance). In the long term, human resource management practices must be able to increase the job satisfaction and productivity of employees for the sustainable competitiveness of firms.

Useful Websites

Bank of Thailand (BOT): www.bot.or.th

Federation of Thai Industries (FDI): www.fdi.or.th

Hongkong Shanghai Bank (HSBC): www.hsbc.co.th

Ministry of Labour Protection and Social Welfare: www.mol.or.th

National Statistical Office of Thailand (NSO): www.nso.or.th

Personnel Management Association of Thailand (PMAT): www.pmat.or.th

Siam Cement Co. Ltd. (SCG): www.scg.co.th

http://hrm.siamhrm.com/ (in Thai)

www.themanager.org/Knowledgebase/HR/SHRM.htm

www.pttep.com/en/aboutPttep.aspx?changelang=1 (accessed 31 October 2011)

Thailand Management Association of Thailand (TMA): www.tma.or.th (all accessed 31 October 2011)

References

Amit, R. and Shoemaker, P. (1993) “Strategic Assets and Organizational Test,” Strategic Management Journal 4(1): 33–46.

Becker, B, Huselid, M. A. and Ulrich, D. (2001) HR Scorecard: Linking People, Strategy and Performance. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2010) Thailand: Staff Report for the 2010 Article IV Consultation, 3 September 2010.

Kamoche, K. (2000) “From Boom to Bust: The Challenges of Managing People in Thailand,” International Journal of Human Resource Management 11(2): 452–468.

Lawler, J. J. and Siengthai, S. (1997) “Human Resource Management Strategy in Thailand: A Case Study of the Banking Industry,” Research and Practices in Human Resource Management 5(1): 73–88.

Lawler, J. J., Siengthai, S. and Atmiyananda, V. (1997) “Human Resource Management in Thailand: Eroding Traditions,” in C. Rowley (ed.), Human Resource Management in the Asia Pacific Region. pp. 170–196. London: Frank Cass.

Pinprayong, B. and Siengthai, S. (2011) “Strategies of Business Sustainability in the Banking Industry of Thailand: A Case of the Siam Commercial Bank,” World Journal of Social Sciences 1(3): 82–99.

Siengthai, Sununta (1993) ‘Tripartism and Industrialization of Thailand’, research paper prepared for the ILO, December.

Siengthai, Sununta (1999) ‘Industrial Relations and Recession in Thailand’, research report prepared for the ILO.

Siengthai, S. and Vadhanasindhu, P. (1991) “Management in the Buddhist society,” in J. Putti (ed.), Management: Asian Context, pp. 222–238. Singapore: McGraw-Hill.

Siengthai, S. and Bechter, C. (2001) “Strategic Human Resource Management and Firm Innovation,” Research and Practice in Human Resource Management 9(1): 35–57.

Siengthai, S. and Bechter, C. (2004) “Human Resource Management in Thailand,” in P. Budhwar (ed.), HRM in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Rim, pp. 141–172. UK: Routledge.

Siengthai, S. and Bechter, C. (2005) “Human Resource Management in Thailand: A Strategic Transition for Firm Competitiveness,” Research and Practice in Human Resource Management 13(1): 18–29.

Siengthai, S., Dechawatanapaisal, D. and Wailerdsak, N. (2009) “The Future Trends of HRM in Thailand,” in T. Andrews and S. Siengthai (eds), The Changing Face of Management in Thailand, pp. 113–145. United Kingdom: Routledge.

Siengthai, S., Lawler, J. J., Rowley, C. and Suzuki, H. (2010) The Multi-Dimensions of Industrial Relations in the Asian Knowledge-Based Economies: An Enterprise-based Case Book. Oxford: Chandos Publishers.

Suehiro, A. and Wailerdsak, N. W. (2004) “Family Business in Thailand: Its Management, Governance and Future” ASEAN Economic Bulletin 21(1): 81–93.