Chapter 4

Checking the Idea Before You Start

In This Chapter

Checking that your project is really a project

Finding the right people and appointing them

Taking on board lessons from earlier projects

Writing a rough (Outline) Business Case

Identifying important planning information

Sketching out the project idea – the Project Brief

Planning the first stage of the project up front

Starting up – the processes and products you use

PRINCE2 gets going before the project gets going, and this chapter looks at the part of PRINCE2 that you do before the project: You take a quick look at the project idea to provide information for an important management decision – whether to start the project and get stuck in to planning it in detail, or abandon the whole idea because it doesn’t look worth it after all.

The PRINCE2 name for this pre-project work is, predictably, ‘Starting Up a Project’. This chapter describes exactly what that work is and the key points to help you run this first part of PRINCE2 effectively and successfully.

Understanding ‘Starting Up a Project’

PRINCE2 has seven processes that walk you through your project and ‘Starting Up a Project’ is the first of these. Like the others, Starting Up a Project – or ‘Start Up’ for short, then has activities inside it. (Have a look at Chapter 2 for more on how to use the processes.) Remember that you don’t follow the activities as a slavish list. They’re more like a checklist and can sometimes really help you because you can see what you can safely leave out of your project, as well as what you do need to cover.

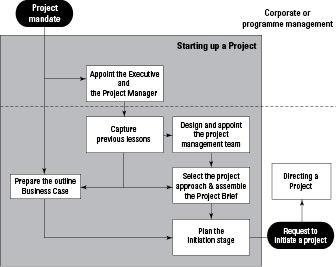

As with all of the process models in this section of the book, have a quick look at the diagram in Figure 4-1 to get the general idea, and then come back again at the end of the chapter when you’ve read all about it. The models can look a bit intimidating at first, but after reading all about them they’re simple enough.

Figure 4-1:The Activities in Starting Up a Project.

Seeing Why You Really Need Start Up

Imagine that I ask you to plan my project, ‘The Office Move Project’. With just this information, can you get on and produce a set of plans? Actually, no. After pausing for a moment to think about it you fire off a whole series of questions:

What exactly is this project – who’s moving?

Are there any constraints on the move – for example, do you need to stay in the city or move outside it?

How much money is available?

Do you face financial restrictions, such as when you can spend money?

Do you have a time limit by which you must complete the move?

Does this project include selling the old building, or is it literally just the move and another project perhaps deals with the sale?

Before you get into the detail of planning any project, you have to sort out some basic things and collect some basic information. Welcome to Start Up. This is important stuff and you can’t go on to planning until you know this information. So you can now see that starting PRINCE2 before the project itself is rather logical.

But Start Up also answers an important question – ‘Is this really a project at all?’ Perhaps the task is just a simple unit of work that doesn’t justify the overheads of project control. Or perhaps the really great idea for a project isn’t so great at all, except in the mind of the person who suggested it!

Next, Start Up helps you, well, get started. You appoint some people to manage the work. You set down what the project actually is. You look at likely costs and benefits. You check on any constraints such as on technology or delivery date. Then you put all this information together in order to make a decision on whether to proceed to full planning or stop right here.

Getting Start Up Done Fast

You can usually do Start Up very quickly. It may take two weeks, but more likely two days and it can even take just a couple of hours.

Starting Up Start Up – a Mandate

PRINCE2 starts with an instruction, usually a document but it can sometimes be a verbal instruction from the organisation, a Project Mandate. A Project Mandate is effectively an authority to do the Start Up work with a view to running the project. The Mandate can set out a fair amount of detail of what the intended project is about and, if it does, it can save a lot of work that you otherwise need to do in Start Up. However, usually the Project Mandate contains very little information. I know of one project where the mandate was simply the name of the project. But at the very least the Mandate should outline the project idea and name a manager who’ll be the Executive and take responsibility for Start Up and then the project overall. PRINCE2 doesn’t cover what should be in a Mandate, so to be helpful – as always – this book gives you a steer on the sort of information you should normally be looking for in a good Mandate.

With the mandate to hand, you can start the work of Start Up, and the first thing to do is get some people in place.

Filling Project Roles

Clarity in ‘roles and responsibilities’ is very important in projects. Vagueness causes a lot of project communication problems, because people don’t know what they need to do or what other people are doing. Indeed, project roles are so important that two other chapters of this book are devoted to them. This chapter summarises the main roles, but you can find the full detail in Chapter 12, which deals with the Organization theme. Chapter 10 is also relevant as it covers how to set up a successful Project Board (the senior management group with oversight of the project).

Appointing the first two key people

The first two appointments are an Executive, who has overall control of the project, and a Project Manager. The organisation’s management appoints the Executive. The Executive must be able to take a business perspective. If a Project Manager hasn’t already been identified by someone in the organisation, then the Executive must find and appoint a suitable person. Although you can divide most PRINCE2 roles between more than one person where necessary, these first two roles are the exceptions. You can only have one Executive and one Project Manager in a PRINCE2 project.

Selecting the Executive

The Executive is a vital role in PRINCE2. The manager taking the role of Executive must

Have a strong business viewpoint

Have an aptitude for seeing things clearly and in the full context of the project and the business

Have sufficient authority to make project decisions

As well as decision-making authority the Executive needs to have the courage to take action, perhaps very bold and decisive action, where justified.

Deciding on the Project Manager

The role of Project Manager is a key one. The Project Manager is someone with project skills and, particularly at this early point, project planning skills. The Project Manager has day-to-day responsibility for the project and works for the Project Board.

As well as having strong management and project skills, the Project Manager must also have a practical understanding of how to apply the PRINCE2 method to make it work well and productively. Like the Executive, she must have sufficient time available to devote to the project.

Appointing more Project Board roles

If you look back at the process diagram at the start of this chapter, you can see that the remaining appointments are made after looking at lessons from previous projects. But here, we’ll carry on and deal with all the roles now so as not to chop and change the subject.

In PRINCE2 the Project Manager’s boss is the Project Board. The members of the Project Board, not the Project Manager, ‘own’ the project.

The board members are active and extremely important to the project. The Project Board has three roles and these represent the three key interests of

Business

User

Supplier

The Executive represents the business interest. Within the Project Board, the Executive is in ultimate charge and always chairs the meetings. For more on the role of Executive, flip back to the section ‘Appointing the first two key people’, earlier in this chapter.

Although the Project Board incorporates three roles, it doesn’t necessarily have to contain that many people, though it often does. Because of role sharing the board may involve more than three people, but a top limit is around six people. The minimum number is just one person, who takes on all three roles. Personally I always think that a better minimum number is two because then you have someone to talk things through with other than the Project Manager.

Choosing the Senior User(s)

The Senior User represents the viewpoint of users and is responsible for specifying, then delivering, the business benefits of the project. A suitable person for this role is someone from the management of the business area that the project affects: the people who actually use what the project delivers. If the project affects more than one business area, the Executive may appoint more than one person to the Senior User role on the Project Board, and they then share the role.

As well as checking that the project delivers things that are ‘fit for purpose’ for the business area, the Senior User(s) must also provide user staff for the project. The project may need this resource, for example, to help specify what the users require and to test project deliverables to make sure that they work in the way the users want. The Senior User(s) must obviously have authority to commit that resource.

Selecting the Senior Supplier(s)

The Senior Supplier is a manager who can commit team resource to the project and who represents the viewpoint of suppliers. Again, if more than one area is involved, you may want to appoint more than one Senior Supplier. You can find out more about the Senior Supplier in Chapter 12.

Dealing with Change

The Project Board members normally make decisions on project changes that are beyond the authority they’re willing to delegate to the Project Manager. However the Board has an option to set up a Change Authority and delegating some of its authority to make changes to this intermediate level – it comes between the Board and the Project Manager. If you cringe at the thought of it, you’re right that it can be problematical as well as helpful, and Chapter 16 on Change includes an examination of the pros and cons.

Ensuring Project Assurance

Project Assurance is basically auditing – checking that the project runs correctly and that complete and accurate information gets to the Project Board. In a small project the individual board members themselves often do this assurance work. In a larger project the board may appoint people to do the checking on their behalf and report back, though they can still do the work themselves if they want to.

Deciding on the remaining roles

Other roles involved in administration and managing project teams are not part of the Project Board but are included in the management of the project and form the rest of the PRINCE2 Project Management Team.

Providing Project Support

Project Support at its simplest is administrative support. Providing a good administrator rather than having the Project Manager spend a lot of time on routine administration makes sense and is more effective, including cost-effective. The administrative support also means the Project Manager can concentrate on running the project rather than be distracted with routine admin.

Some organisations have a central Project Office that supports all their projects. Projects finish and new ones start, but the Project Office is permanent, helping all the current projects. A particularly large project may justify having its own Project Office.

Allocating Team Manager(s)

The PRINCE2 method may only involve one Project Manager, but you can have many Team Managers. A number of teams may work on the project at any one point. Some of these may be from inside the customer organisation and some may be from external supplier companies. Each team has a Team Manager who reports to the Project Manager.

During Start Up, before the project has got as far as detailed planning, it is often too early to decide on the Team Managers. However, sometimes you’re already clear that you need particular teams, such as an installation team. Where this is the case, you can include these managers and their teams in the list of roles and responsibilities: The project management team structure. In a small project where the Project Manager runs the team, you can leave out the role of Team Manager.

Creating the Daily Log

One of the first acts of the Project Manager is to set up the Daily Log. This has a couple of functions. The first is like a diary in which the Project Manager can note reminders, actions and other day-to-day information. The log is very useful and can save a lot of paperwork when used intelligently. For example, the Project Manager may record a decision and thereby save the need to write and send letters or memos. The second function is as a ‘catch all’ to record any project information that none of the other PRINCE2 management products cover. Having said that, PRINCE2 is quite comprehensive, so this second use is rare.

In Start Up, the Project Manager starts to use the Daily Log straight away. For example, to record information such as risks that will later be transferred to the more formal Risk Register if the project goes ahead to full planning – Initiation.

You can have a completely unstructured format to the Daily Log, just a date and some text. PRINCE2 does suggest some headings though.

Learning Lessons from the Past

It’s been said that history repeats itself because nobody listens the first time. It’s sad when a good project fails, but tragic if it’s for the same reasons that a previous project failed (yes, it still happens) because nobody ‘learned the lessons’. But sometimes you can miss out on good things too. Perhaps something different was tried out on a previous project and it worked really well and you can repeat the trick in this project.

PRINCE2 looks at lessons in two time frames. One is a look into the future. The method uses the Lessons Log to record things found out in this project – good stuff as well as bad stuff – to pass on to future projects. But the second is here, at the start of a project, to look back at previous experience – the lessons learned from the past.

You create a Lessons Log for the project now, at this point in Start Up, and then write into it the things you need to bear in mind in this project. The PRINCE2 manual gives three ideas of where to get information, but with a bit of thought you can do better than that.

Lessons Reports from previous projects (where they reported information based on their Lessons Logs) and any other reports from those projects

Corporate guidance, if you are in a large organization.

People who worked on a similar project run previously in your organisation: Project Managers, Team Managers and team specialists.

People in similar, non-competitive, organisations. This can be especially useful in the public and charity sectors. If you find an organisation that has already run a project similar to yours, you can often find someone willing to spare you some time if you visit, or even in a phone call, to share experience and some tips.

Your own personal notes of what has worked for you on previous projects and what didn’t.

Project articles in the specialist press.

Reviews and reports on the Internet – some surprisingly candid information is around.

You can use this lessons information in the other activities in Start Up, such as Design and Appoint the Project Management Team. ‘Whatever you do, don’t let X or Y even get near a project – they’re the kiss of death.’ Well, hopefully not quite that, but you get the idea.

Checking the Project’s Viability

You can easily get enthusiastic about some great project idea and rush into planning it (or not!) and ‘getting on with it’. Often the urgency comes from a senior manager who has at last managed to find the resource to run her wonderful project. Now she wants to ‘get on with it’ and fast – or, more often, she wants you to get on with it and really fast.

But jumping straight into a project isn’t a particularly good idea. You need to validate the idea to make sure that this really is a worthwhile project. The UK Treasury, the government department responsible for government finance, has a document called ‘The Green Book’. The Treasury produced this for government employees who have to write business cases for their work, including projects. The document’s freely available as PDF files and you can download it and print it off if you’re interested – simply search for ‘HM Treasury Green Book’ on the Internet.

The Green Book describes the common problem of ‘optimism bias’. It says that managers tend to be over-optimistic in two areas. First, they think that the project can run at lower cost and faster than is really the case. Second, they think that the project can deliver considerably more business benefit than is actually the case.

I was talking to a very experienced project consultant a while ago and we agreed that far too many projects start with high expectations but finish with disappointing results, to the point of being a failure. Or projects stop part way through when managers realise that the project can’t deliver anything like the level of benefits anticipated.

You can often prevent such costly mistakes with a short upfront review of the project that estimates likely costs, timescale, benefits and possible risks. This upfront review is exactly what PRINCE2 does in Start Up.

Writing the Outline Business Case

And please note the ‘outline’ bit. The Business Case at this point is rough and not the polished and full justification that comes when the project is planned in detail – if it gets that far. At this point, in Start Up, the Outline Business Case is to support the decision on whether it’s worth going forward into full planning (Initiation) or not. It may be that very little information is needed to make that decision.

Producing the Project Product Description

Having said that this is about the Outline Business Case, the method actually requires something else before starting work on the business aspects. That is, to define what it is that the project is going to deliver. That definition is documented in the Project Product Description.

To make sense of this part, you need to take on board that PRINCE2 focuses on project deliverables, or ‘products’. Chapter 14 is dedicated to this ‘Product-Based Planning’ approach. The chapter explains how to set about planning with products, including writing a Product Description for each deliverable that defines what the product is, what quality criteria it must reach and how it’s to be tested to make sure that it does. The Project Product Description is basically the same, except that it’s for the whole project and some of the content is slightly different.

The information here is sensible, but as always in PRINCE2 you can adjust it in any direction. You can add extra sections in a more complicated project environment, or take some out if you don’t need them. If you do need to add anything, do remember that you’re in Start Up at the moment and try to keep things simple. You can always adjust it a bit in Initiation when you do the full planning.

A Business Case, put simply, is the justification for a project. Normally, a viable case shows that the benefits of running the project are significantly greater than the costs. But be careful to keep your brain in gear because benefits aren’t the only justification. The project may be justified on different grounds, such as compliance. The project is being run, for example, because it’s a head office instruction, and the fact that little or nothing exists in the way of benefit is immaterial.

For the full detail of the Business Case, please turn to Chapter 11. You can find all of the section headings for it there, it’s just at this point in Start Up some sections are missed out and others only have skeletal information in them. For example, you’re not usually going to do investment appraisal in the rough Business Case in Start Up, but you may do substantial appraisal work later on when you produce the full Business Case.

Getting Business Case approval

Although the Executive with the rest of the Project Board has authority to make decisions, they don’t always have the authority to approve the Outline Business Case. In that case, as soon as it’s prepared and has been agreed by the Project Board, the Outline Business Case passes to whoever in the organisation can give approval. No problem, but do take into account any time delay involved in going through an approval process. This is particularly so if, perish the thought, the Outline Business Case has to go to a committee.

Checking the Approach and Writing the Project Brief

After looking at things like the roles and the Business Case you can now get down to thinking more about the project itself. Unless you have some devastatingly boring financial project to do, this thinking is good fun.

There are two parts to this activity. The first is to look at something PRINCE2 calls the Project Approach. This information on how you need to ‘approach’ the project may include constraints, such as on the type of equipment you have to use or the security requirements you need to observe. The second is to write the Project Brief, which is a sort of sketch plan of what the project is about. We’ll take these one at a time because being a dummy I can’t write in stereo – but don’t be too critical because you probably can’t read in it either.

Thinking through the Project Approach

Identifying key project information is an extremely useful, but often neglected, part of Start Up. You need to think about any constraints that may affect the planning and control of the project, as well as the outcome. You then record this information in the Project Approach which goes on to form part of the Project Brief.

The Project Approach can list constraints on the outcome of the project, or the ‘solution’ if it’s that type of project, but it should also include any other information that affects how the project should be plan and run.

When considering how to approach your project, think about:

Resources: You may face a constraint to use only internal or only external staff, for example.

Security: The project may need to meet a particular security level, which in turn may affect resource planning of who can do what.

Legal/compliance: Legal constraints may exist, such as health and safety regulations, and financial or industry codes of practice that the project must comply with.

Type of solution: For instance, when you require a computer system and have to buy a packaged solution, the project is simply to find which is the best system.

Technology: You may need to stick to a particular brand of machinery on the production line, for example, so that the company doesn’t have to maintain lots of different brands with many different maintenance contracts.

In the Project Approach you can set out the options in different areas such as resources or technology, and then you can state the options selected together with their reasons. That selection may be done by people such as Project Board members or technical experts and not the Project Manager. However, you can also use the Project Approach more simply, just to list the things that affect planning.

Writing the Project Brief

The Project Brief needs to be . . . well, brief. A common mistake is to do far too much work and go into completely unnecessary levels of detail. In turn, that extra work extends the Start Up period – instead of getting through the work quickly, it takes weeks or even months.

To illustrate this, assume that you’re a very senior, intelligent and highly paid member of staff – which is almost certainly true if you’ve had the foresight to buy this book to see how to use PRINCE2 well. You decide that to use up some of the huge amount of money your organisation pays you each month, you want someone to build a house for you. You go to an architect and say that you want a house, please. What does the architect reply? ‘Yes, that’s fine. I’ll get busy on some scale drawings and come back to you in eight weeks’? No. Instead the architect gets some scrap paper and asks you to sit down and describe the sort of house you have in mind. She draws a sketch as you talk. ‘Okay, 50 bedrooms, 51 bathrooms (always good to have a spare), a huge living area overlooking the lake and mountains . . .’ When you say, ‘Yes, that’s pretty much what I have in mind,’ the architect then goes off to produce scale drawings that comply with planning and building regulations. The process starts with a sketch, not full architectural drawings.

The Project Brief is that sketch on some scrap paper, not the architectural drawings for the project. If you decide to go ahead with the project, more detailed planning produces the project equivalent of scaled drawings.

Although the PRINCE2 activity refers to assembling the Project Brief, actually that’s only part of the job. You do quite a lot of thinking, discussing and writing before actually getting to the point of assembling the whole brief.

Getting it together with the brief

Keep the Brief as simple as possible: The headings of the document make a useful framework to explain the information and where it may come from. Some of the information may come from the mandate – possibly a substantial part, depending on how good the mandate is. (For the lowdown on the mandate, see the section ‘Starting Up Start Up – a Mandate’, earlier in this chapter.)

Getting the Brief together does need some effort, but you’ll recognise a lot of the content from the earlier Start Up activities – so expect quite a few references back to things covered earlier on in the chapter.

Project Definition

As the name suggests, the Project Definition sets down exactly what the project idea is. If the idea isn’t clear – which isn’t at all uncommon – you may need a lot of discussion first. Some subsections of the Project Definition can help you with this.

Background

The Background describes how the project idea came into being. It sets the rest of the definition into context.

Project objectives

For the same project, different people can have different objectives. The project objectives set down the agreed objectives that everyone can then sign up to. PRINCE2 locks these objectives into the context of achieving goals for each of the six control factors: Time, cost, quality, scope, risk and benefit performance. You may find that a bit limiting. If so you can always add on objectives that don’t fit easily into these categories.

Project scope and exclusions

Project scope and exclusions constitute a valuable section, not only because it sets down what is part of the project, but also because it specifies what is not. Knowing the project’s scope is important in managing expectations. A list of what’s in the project isn’t necessarily enough, and at the end business users can be disappointed because you haven’t included something and the business area didn’t notice it was missing from the scope. These exclusions aren’t the whole of the planet outside the project, but rather those areas where misunderstanding may occur.

Saying what the project excludes has two valuable benefits. First, doing so manages expectations so that the business area can see what it will get and what it won’t get. Second, specifying the scope and exclusions can lead to a challenge. The business area may argue that the scope shouldn’t exclude the element concerned but rather make it part of the project. They may prefer to have that in place of another part if the organisation doesn’t have the time and resource to do both. Adjusting the project boundaries may be very beneficial in getting a better project.

You can specify the scope according to function, as in the example just given, or by departmental area, or sometimes even by time. In a project to prepare a major mountaineering expedition, the scope may be time based, to include everything up to arrival at base camp with the right people and the right equipment.

Constraints and assumptions

Although you may identify constraints on the scope, don’t confuse them with things like planning constraints (see Chapter 14 for an idea of what these include). Constraints in this section of the Project Brief typically refer to the minimum scope that the project will cover.

Project tolerances

You may know some project tolerances at the outset and if so you can set them down in the Project Brief. A tolerance is an acceptable range that always has a plus and a minus. You may state this as a number or percentage, but usually working with a numeric range is easier. So, a project to investigate a business process and suggest improvements should take 12 weeks, plus or minus five days. It may sound a bit odd to say minus five days but it represents completing the project ahead of schedule. A minimum time may be sensible if the organisation wants the investigation to be thorough.

The two tolerance limits don’t have to be the same. You can specify, for example, that the project tolerance is plus five days and minus ten days or plus £10,000 and minus £5,000. Tolerances can apply to different elements such as the project’s scope, but the most common areas are time and cost.

The user(s) and any other known interested parties

This section refers to stakeholders, which includes those who’ll use what the project finally delivers, but goes beyond to others who may be affected. Again, you may not know all of them at this point, but you can list the ones you do. This will be helpful in working out who to involve and consult when doing the detailed planning in Initiation and as a start to stakeholder management.

Interfaces

This section shows how the project may interface with other areas. Interfaces can include:

Other business areas that have links with the area that the project covers.

Other organisations that the project outcomes may affect and that you need to consult. This element can be especially important if you’re in a public-sector organisation.

Interfacing business procedures that use outputs from an area covered by the project, or provide inputs to it, or both.

Related projects that can have an impact on this project, and vice versa.

Outline Business Case

The Business Case is the justification for the project idea. This section of the Project Brief sets down the business benefits, the estimated cost of the project and the project’s likely timescale. See the section ‘Writing the Outline Business Case’ earlier in this chapter, and for the full detail see Chapter 11.

In the Outline Business Case you also need content to show that the project lines up with organisational strategy and policy, not working against the rest of the company or going off at a tangent.

Project Product Description

Have a look at the section earlier in this chapter ‘Producing the Project Product Description’. You make this definition while working on the Outline Business Case and it includes the quality level required in the project required by the customer: The Customer Quality Expectations. What you need here for quality is an idea of the overall level for this particular project idea. On the one hand, the project may be safety-critical where people’s lives depend on the quality of the deliverables, and the quality-related work, including quality planning, is considerable and rigorous. At the other extreme, the project may be ‘quick and dirty’ and justifiably exempted from the normal minimum quality requirements in the organisation’s projects.

Putting the Project Product Description in the Brief can be helpful in two ways. First, some people find it hard to grasp what some projects are about, but if you say clearly what the project will deliver, they immediately understand. Second, two people can talk about the same project idea but have very different ideas about what the final deliverable may be. In either or both cases, this section makes the outcome clear.

Project Approach

This is described in the section earlier in this chapter ‘Thinking Through the Project Approach’. This information is extremely useful when doing the full planning in the Initiation Stage, and even before that towards the end of Start Up when you’re planning the Initiation Stage.

Project Management Team Structure

The good news is that this is really simple. You’ll have decided, normally, on roles and responsibilities earlier in Start Up. See the section earlier in this chapter ‘Filling Project Roles’. Now you get to play with a diagram editor to draw up an organisation chart for the project. You can spend happy hours adjusting the layout and colours – or perhaps you’re much more disciplined than me.

Role Descriptions

Don’t get carried away here. The PRINCE2 manual, contrary to the impression it gives, can save you some serious time and often you just don’t need to do role descriptions. If your use of roles is standard, you don’t need to start writing detailed descriptions because they’re all printed out in Appendix C of the manual. Concentrate instead on spelling out anything that is non-standard – if you have any roles that are non-standard.

You can find much more on roles in Chapter 12 on the Organization theme.

References

This is where you record any references to other documents. You might refer to an organisational strategy, for example, or a policy paper that has a bearing on the project.

Planning the Planning: Initiation

The final part of Start Up is to prepare for the Initiation Stage. If the Project Board decides to start the project and run the Initiation Stage then you need to have a plan in place so that you can start the work without delay.

When you plan Initiation, don’t forget any work to create baseline measures. If the Business Case claims that the project is going to make a 15 per cent saving in costs over the present business procedures, do you know what the business procedures cost at the moment? Similarly with claims for time savings – do you know how long current procedures take? In order to measure the savings of the ‘after’, you need to have accurate figures for the ‘before’. You need to include work to take those measurements in the Initiation Stage plan.

Deciding to Plan in Detail – or Not

At the end of Start Up, a package of information goes to the Project Board, who then decides whether to go ahead with the project and authorise work to start on the Initiation Stage and do the full planning, or whether to stop things at this point because the project doesn’t look viable.

If the board does decide to go ahead, its members are only committing to the Initiation Stage at this point. Only at the end of the Initiation Stage, if things still look good, does the board commit to the whole project.