Chapter 5

Planning the Whole Project: Initiation

In This Chapter

Thinking through risk, quality, change and communications and how best to manage them

Deciding on the degree of control you need and what mechanisms to use

Planning the work of the project

Working the Business Case into full detail

Creating the Project Initiation Documentation (PID)

Chapter 4 is about the PRINCE2 process of Starting Up a Project and how the Project Manager and the Executive produce a Project Brief. The Project Board uses this ‘sketch plan’ of the potential project to decide whether the project looks worth planning in more detail. And that’s where this chapter comes in. Initiation is that planning in more detail.

The first project stage, which is driven by the process ‘Initiating a Project’, is devoted entirely to project planning and doesn’t involve any other work. A very common cause of project failure is poor planning – or even a total lack of planning – and this stage in a PRINCE2 project helps to make sure that doesn’t happen.

The completed set of project plans form the Project Initiation Documentation or PID, a precise definition of exactly what this project is. But then you also need to plan in more detail for the first delivery stage of the project (the one after the Initiation Stage), so that if the board decides to go ahead with the full project the first of the delivery Stage Plans is in place and ready to roll.

Getting to Grips with Initiating a Project

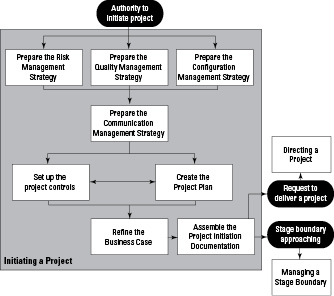

As with all of the PRINCE2 processes, a lower-level model of Initiating a Project shows you the activities that are inside. It gives you a road map of what Initiation is all about. Have a quick look at Figure 5-1 now. It may look a bit complicated but after you’ve read this chapter, the detail falls into place and you see it’s actually quite simple.

Figure 5-1: The activities in Initiating a Project.

Initiation involves some big subjects like risk, quality and planning so expect lots of references to other chapters where these themes are covered in more depth. As you’ll see, this chapter gives you the main things to bear in mind, but the main subject chapters give more detailed coverage.

Understanding Why You Need Plans

So, the first stage in every PRINCE2 project is the Initiation Stage. This stage is mandatory in the method and the word ‘initiation’ here basically means ‘project planning’, but in the widest sense of those words. The activities in the process give you a helpful checklist of what you need to think about and work through.

The argument for planning is really a no-brainer. When you go on holiday, you have to think through what you need and plan your trip. With a project that may be business-critical to your organisation, planning is even more important.

When working through any project, problems always crop up – some predictable and obvious and others that come out later during the project work. So when do you want to find out about the more obvious problems and deal with them? While planning, so you can sort out those problems on the plan, or would you prefer to hit them during the project itself? Clearly, if you find the problems during planning, you can deal with them at that point and the project will then run more smoothly. Some unforeseen difficulties are still bound to occur, but why struggle with other things that you could have noticed and sorted out earlier? The time and energy you waste in ‘fire fighting’ all the problems is much greater than the time taken to plan things properly in the first place.

A further argument for effective planning is project control. In order to monitor progress, you need to have something to measure against – a plan. If you don’t know where you expect to be at any given point, how can you know whether you’re on track?

Looking at What’s in the PID

It’s easier to understand the process Initiating a Project if you have a quick look at the contents of the PID first. Then as you work through this chapter you’ll see that Initiation simply covers the thinking, consultation and writing needed to produce the various sections.

Because the PID defines what the project is and what the Project Board approves, you can see it in terms of a contract between the board and the Project Manager. This is the project that the Project Board is asking the Project Manager to run on a day-to-day basis on their behalf, and the PID gives the Project Manager the authority to do that.

Getting Strategic

The first four activities in the process are about thinking through how you’ll manage four key aspects of this particular project: Risk, quality, version control and communications. For each of these four you develop a strategy, which is usually a written document.

Thinking about risk management

The first strategy is the Risk Management Strategy. This is an overall strategy so don’t confuse it with how you plan to deal with individual risks. Information on the management of each individual risk is contained in the Risk Register that you also create during this activity. More on the Risk Register in a moment.

The Risk Management Strategy is how you’ll manage risk overall on this project. For example, who is able to take decisions about risk? Do any procedures need to be put in place and if so what should they be? Should there be a separate budget for risk management within the project? How should risk status be reported? For full details on the Risk Management Strategy go to Chapter 15, which focuses on the risk theme.

Opening the Risk Register

Information on risks that are to be formally managed should be put into the Risk Register but as you haven’t got one yet, now is the time to create it. The full information on this, including the register headings, is in the risk chapter, Chapter 15. The register can be set up by Project Support – the administrator function in the project – but normally the Project Manager can set it up faster than reaching for the phone to ask Project Support to do it. In my training company, Inspirandum, we provide a full set of templates free to everyone who books us for a course and they can really speed things up when creating the basic control documents in a project.

PRINCE2 allows for risks to be managed in two ways. Formally, by entering a risk into the Risk Register, or informally by the Project Manager by just keeping track of that particular risk in his Daily Log. Up to this point the Project Manager has only had the Daily Log and any risks identified during Start Up were noted in that. So now, those risks that should be formally managed are transferred to the Risk Register.

Analysing risk during Initiation

You may well decide to do some risk analysis at this point too and work the Risk Register up into full detail, though the official PRINCE2 manual is strangely silent on the point. In Start Up you only list the main risks and even then only in basic detail. In any risk analysis you record the full details on each risk in the Risk Register, including exactly how you’re going to handle them in the project. That’s not the end of the story though because you’ll undoubtedly find more risks as you go through Initiation – not least while you are developing the project plans – and so you can expect to add more risks and do more analysis before you’re done with this ‘Initiating a Project’ process.

Watch out, because risk analysis can take quite a lot of time and it involves the Project Board as well as the Project Manager. But as always, balance this. If the project is very low risk you may not need too much time and effort on it, no matter how large the project. But equally, don’t cut back too much. Better to spend a bit more time now and manage the risk really well, than find you need time-consuming and costly effort later in the project because you didn’t see problems coming that you could have spotted easily if you’d done a bit more work in Initiation. Who knows, a bit of thought may mean that by taking some very simple actions, you can prevent some of the risks ever happening at all.

Thinking about quality management

In this book I make the point several times that project management isn’t just about time and cost – the two things that many organisational managers are exclusively concerned with. What’s the point of delivering a load of unusable garbage ‘on time and within budget’? Clearly, producing the products – the project deliverables – to the required level of quality is of prime importance.

PRINCE2 has a very strong focus on quality, deeply embedded in the method. You think about quality even before the project – in Start Up. But the real quality work begins now, in Initiation, when you think through a strategy for quality across the whole project and record it in – you’ve guessed it – the Quality Management Strategy.

You may think it odd to tackle quality early in Initiation, and before you’ve done the project plan. But as you get to grips with the Initiation work you can see the logic. When you get to the project planning you then benefit from knowing the overall level of quality you’re aiming for and the sort of things involved with that, such as the amount of testing, what skills and resources you’re likely to need, and the timing of some quality activities.

Most of the time you decide on individual tests and their timing when you do the really detailed quality planning as part of stage planning just before each stage begins. However, some things go across stages. For example, you may need to book a fire officer in Stage 3 for a fire inspection that you need in Stage 6. If you think through what standards you need to comply with as part of your quality strategy here, early on in Initiation, you note that element and keep it in mind for when you come to the project planning.

The Quality Management Strategy is, not surprisingly, strategic while the quality work in stage planning is more tactical. You leave the tactics of exactly what tests you need and when and who is to do them, for that stage planning, when you have a clear picture of the precise requirements for things you’ll be producing in that part of the project.

Get real – not every project is safety critical

Some people think – wrongly – that good projects should always achieve the very highest levels of quality possible. That idea’s a long way from the truth. The PRINCE2 method is more realistic than that, and you need to be realistic as well.

The correct level of quality for your project may genuinely be a low level. Running a ‘quick and dirty’ project to do something rapidly without rigorous quality isn’t at all wrong. Not every project is safety-critical with thousands of lives hanging in the balance. That doesn’t give you an excuse to abandon quality where you do need it, but it does emphasise the need to balance the level of quality against the needs, the cost, and the time you require to achieve it.

Writing the Quality Management Strategy

Chapter 13 covers the full detail on quality management in PRINCE2, including the strategy. But here are a few things to bear in mind now.

First, establish just what level of quality you’re going for – for that you may need to talk to other people:

Project Board members: Ask what they need from a customer viewpoint and what they want to pay for.

Known suppliers: Discuss quality in the specialist parts of the project. Technical or industry standards may be involved.

Specialists: Find out about any specialist quality requirements they have, perhaps including legal constraints.

The Quality Department (if you have one): Establish organisational quality requirements such as quality procedures, standard checks and quality responsibilities.

But the Project Board itself does the main quality decision-making. The board includes the Senior User, who says what the user community requires; the Senior Supplier, who’s aware of specialist quality requirements (such as industry codes of practice); and the Executive, who represents the organisation and who is usually paying for the project.

In the Quality Management Strategy you need to set down what level of quality is appropriate for this project, how to achieve it, and who’s responsible for achieving it. The strategy has to be practical and achievable.

So, for the strategy you need to think through and record:

Who: Who’s responsible for delivering and checking quality? This can include people from outside your project (perhaps from head office) or even from outside your organisation (perhaps building inspectors).

What: What level of quality do you want to achieve and what level do you need to achieve? For example, you may face legal requirements such as safety standards, as well as what the business users want to have.

How: What controls and procedures do you plan to put in place to make sure that you actually deliver the required quality and don’t just talk about it?

Thinking about outside suppliers

For the Quality Management Strategy you need to think carefully about any project teams from outside your own organisation – perhaps from supplier companies. Their approach to quality may be entirely different to yours. These project teams may have different patterns of quality responsibility, different procedures and different ways of approving products. Your strategy may need to include mapping these teams’ quality procedures to show how they’ll align to, and interface with, your own project procedures.

Updating the Quality Management Strategy throughout the project

You may be wondering what you do if you don’t yet know who your external suppliers are, because your organisation isn’t going to award the contracts until part way through the project. Don’t worry, this is quite common and PRINCE2 covers that – of course! Although the Quality Management Strategy forms part of the PID and the Project Board use it to give the go-ahead at the end of the Initiation Stage, it is then kept up to date throughout the project. The Project Manager can update the strategy at the end of each stage, so any new information, such as the details you need to deal with different suppliers’ procedures, can be put in then.

Preparing the Quality Register

The Quality Register is effective and simple, an excellent combination. It acts as an audit trail to help with project assurance and to make sure that planned tests and checks actually get done.

The Project Manager, or Project Support on his behalf, makes entries in the Quality Register before the start of each stage, listing all the planned quality activities, such as tests and checks, each with a reference number and the target date on which it is due to take place. When a test or check is done, the testers sign it off in the Quality Register and the Error Sheet or other test notification is often filed in the register too. Signing the register shows that the test was done and the Error Sheet demonstrates that the team cleared any errors. It’s a good idea to file each Error Sheet as extra evidence of a test, even where there is a ‘nil return’ because no errors were found in the product.

Team Managers, the Project Manager and Project Assurance staff will repeatedly check the Quality Register, and each of those checks takes mere moments. These repeated checks mean that forgetting a test is just about unimaginable.

For more information on the whole topic of quality, see Chapter 13. You will find full details there on the exact contents of the Quality Management Strategy and the Quality Register.

Thinking about Configuration Management

Thinking about . . . what? If you’re not from an IT or engineering environment you may wonder what on earth Configuration Management (CM) is. Don’t get too worried, it’s basically about controlling versions. ‘So why don’t they just call it Version Control?’ you ask. Why indeed. But Configuration Management it remains, despite my repeated protests, so you and I have both got to live with it. But look on the bright side, at least we can sound knowledgeable and important. ‘Ah yes Mr Smith. I think we definitely need a bit of configuration management with that one!’

The document you’re working on here is the Configuration Management Strategy. It sets down how you do the version control, and how you protect project products from unauthorised change. The full detail is in Chapter 16, which is about managing change. But as with quality in the previous section, here are a few guidelines for writing the strategy.

Writing the Configuration Management (CM) Strategy

As with the other strategies, remember this is about how you’re planning to control the versions. It’s not about actually controlling them; that happens mostly in the delivery stages. Here you need to think through what protection and procedures you’re going to need. For example, should anyone on the project be able to get at things without restriction or anyone stopping them? Perhaps so, in which case you won’t need any protection. But perhaps you don’t want to allow free rein, so you need to think who can get at what, and what security you need to stop other people getting at information they shouldn’t have easy access to. That may involve physical security such as fences and locks, or perhaps computer security with usernames and passwords.

If project staff can’t just get at something without authority, you need to decide what procedures to put in place to issue documents and make sure that they come back. You may need ‘booking in’ and ‘booking out’ procedures to keep track of who had what, and when. The design of those procedures is part of the Configuration Management Strategy.

Watching out for suppliers

Mapping suppliers’ procedures to your project procedures is very important in this context of CM. What if your external suppliers have different version control procedures and identification systems to yours? Or worse still, if you work in information technology, what if the suppliers have the same procedures and identification systems as yours? If the supplier writes some program code and gives it the same identifier as a different program being written by someone from your own IT department, in the worst case, someone’s code may get overwritten by mistake.

Keeping the CM Strategy up to date

Like the other strategies, you will be keeping the Configuration Management Strategy up to date throughout the project. So if, for example, at the start of Stage 5 you let a contract and the winning supplier has a different CM procedure to yours, you may then need to update the strategy to show the mapping of the two procedures and how the interface will work.

Keeping track of things to be configuration managed

If you’re going to version control something you obviously need to record information about it. In PRINCE2 that is called a Configuration Item Record. It’s far too early to do this for most things because you haven’t even done the planning yet. However, you need to version control some of the project management things as well, such as the Business Case. Because you know about them now, and indeed are working on them during Initiation, you can set up the Configuration Item Records for them here and now.

For the full detail on the information on a Configuration Item Record, have a look at Chapter 16. But don’t be put off by the bureaucratic image that the term ‘Configuration Item Record’ conjures up. The information this record contains is actually very sensible and enormously useful in preventing a range of project problems.

Setting up the Issue Register

Before explaining the Issue Register, it’s probably helpful to say what an Issue is in a PRINCE2 project. An Issue is a communication from anyone with an interest in the project straight to the Project Manager at any time and about anything. Now is that flexible or is that flexible? The Issue may be to ask for something to be changed, it may be to report a problem, it may be to put forward a good idea, it may be, well . . anything. When the Project Manager gets the Issue, he must make a decision about whether to deal with it formally or informally. If his decision is to deal with it informally, he simply records in the Daily Log. Chapter 4 on Start Up explains more about the Daily Log, but in short it’s like a project diary. If the Issue needs to be managed formally, the Project Manager records the details on an Issue Report and then keeps track of its progress with an entry in the Issue Register.

So, having come to the register by following the track of an Issue, you can pretty much guess what it contains. Again you can see that PRINCE2 is pretty logical overall, and therefore predictable. You need to record who sent in the Issue; when; briefly what it’s about; the current status (such as ‘under investigation’) and finally when it was closed so you can tell which Issues have been resolved and which ones are still being worked on. You set up the Issue Register here, in Initiation, ready for use in the delivery stages.

For more on Issues, Issue Reports and the exact content PRINCE2 suggests for the Issue Register, please see Chapter 16 on the Change theme.

Thinking about communications

Hang on in there, this is the last of the four strategies. But actually it’s a particularly powerful and useful one . . . the Communication Management Strategy.

The concept of the Communication Management Strategy is simple enough. What communications do you expect to take place inside the project, from inside the project to interests outside it, and from outside the project into it? This covers things like progress reports and information about risks.

The Communication Management Strategy is helpful because it lists the communication needs so that they won’t be forgotten. But it also includes things like who should receive information and who’ll create it, and when and how the information is to be communicated. You may think that it sounds a bit over the top, but actually it isn’t because it can save a lot of effort. That’s because it can help cut out unnecessary communications and help you make the remaining ones as efficient and appropriate as possible.

Writing the Communication Management Strategy

When writing the Communication Management Strategy, you think through each of the anticipated communications and how best to do it. You can record a lot of this information as a simple table, it doesn’t have to be flowing text. Your list should include:

What information is going to be communicated (information moving around inside the project as well as information going outside it and coming in from the outside – such as progress information)?

Who is to produce the communication?

Who needs to receive it (perhaps one person or a distribution list of many)?

The frequency of the communication (this can be regular, such as a monthly statement, or event-driven, so only triggered when something happens).

The format of the communication (this can be anything from a phone call to a formal presentation).

Thinking wide – not just ‘document’

PRINCE2 is often accused of being paper heavy, but this is based on a misunderstanding. Yes, some documents are needed but some things can be communicated in other ways. The Communication Management Strategy lists how particular communications should be made and the options can include things like presentations, podcasts, websites and even carrier pigeons if you want. Think about the best way of communicating each item and don’t just think ‘document’ no matter what your trainer may say if you’re reading this on a not-so-good-but-cheaper PRINCE2 training course! That last comment isn’t made idly because a lot of over-documentation on PRINCE2 projects results from trainers having taught people that PRINCE2 is about filling forms in.

Remembering that it’s good to talk

British Telecom’s catchphrase ‘It’s good to talk’ is worth remembering here. You don’t have to write reports; they can be verbal. This comes as a big surprise to many organisations using PRINCE2, who wrongly assume that they must write down everything – and then blame the method for creating a paper mountain! But verbal reporting can be fine. For example, if something goes wrong that causes a stage to go beyond limits that the Project Board specified (such as time), the Project Manager must inform the board with an Exception Report to explain the problem and give a recommendation for action. In a small project with few people involved the Communication Management Strategy may record that the Project Manager can give the information to the Project Board using . . . a phone call.

Although I’ve emphasised that over-communication is a problem, you must be balanced here. Problems still do occur because insufficient communication takes place and this can sometimes be expensive.

The Communication Management Strategy doesn’t fit into any of the main theme areas of PRINCE2, so here’s the detail of the headings now. As you can see it isn’t difficult, but you may still want to simplify it for your project.

Deciding on Controls

In PRINCE2 you can’t really say the word ‘control’ without immediately thinking ‘stages’. The project stages are the big control, though you need to think about other controls as well as you work through this part of Initiation.

Breaking the project into blocks

The stages of the project represent the main blocks of work. In PRINCE2 these are management stages that represent the Project Board and Project Manager’s view of the world, not technical stages that are the teams’ view of the world and relate to the characteristics of the activities they’re working on, such as ‘design’ and ‘build’. You may choose to map management stages onto the technical stages, but you probably won’t.

Put simply, a management stage represents a unit of work that the Project Board is happy to authorise in one go. That may be three or four months of work or even more. Clearly, this is a Project Board decision, although the Project Manager may advise and make suggestions on suitable boundary points. A management stage may include more than one technical stage, and the management stages may even cut across technical stages. This may sound a bit messy, but actually it saves considerable time in unnecessary meetings.

The fact that one technical stage finishes and another one starts may hold little interest for a Project Board, except as an indication of progress that you can communicate some other way. To illustrate this point, imagine yourself at a Project Board meeting as a Project Board member. You’re very busy, but you’ve cut an hour out of your busy schedule, plus travelling time to and from headquarters. The meeting starts and the Project Manager tells you that Team C have now finished their work and left the project, and that Team D have arrived and are about to start their work. What’s your reaction? More than an hour of your valuable time was used up – for that! You may gently remind the Project Manager of the existence of the phone and email. The board has nothing to decide and didn’t need to meet. Progress information like that can be communicated more effectively in a simple report; it doesn’t require a meeting.

At what points in the project does the board need to meet? Those mark the management stages. These stages are extremely important in PRINCE2, not least because they provide Project Board control points that are relatively infrequent in the project. The Project Manager will talk about this with the Project Board before putting the stage boundaries onto the Project Plan. You can find much more information on management stages and the factors involved in deciding on them in Chapter 17, which is on the Progress theme.

Setting up the other controls

Other controls include things like progress reporting and problem handling. On progress reporting, at what frequency should progress reports be made and should they be copied to organisational managers, not just to Project Board members?

All projects involve making important decisions and as part of setting up the controls you need to be clear who can decide what. When does the Project Manager have the power to decide and at what point must he refer something to the Project Board for a decision? The Executive has to be involved in deciding authority for the project, because the Project Manager can’t choose his own authority level.

As you can see, project controls in PRINCE2 are generally straightforward, and to make things even clearer it can be helpful to spend a moment comparing it with work in a department in an organisation – a parallel that’s helpful with roles and responsibilities too. In any department, there must be clear authorities so people know when they can make a decision and take action and when they need to refer something to their boss. There must also be clear reporting of progress and problems. Well, so too with the project. The Project Manager must know what authority he has, and everyone needs to know the mechanisms for things such as progress reporting.

Updating the Communication Management Strategy

You may have noticed several references to reporting in this section on controls and if you’re especially wide awake, it may have crossed your mind that this overlaps a bit with the Communication Management Strategy covered earlier in the chapter. If so, you were right. The controls and communications are closely linked and a control decision, such as on reporting, may lead to you adjusting the Communication Management Strategy. No problem, just do it and keep the other strategies in line too as things get clearer as you work through Initiation.

Planning Your Project

The general planning covered so far in this chapter is good, but planning the project work itself is where the excitement really starts! The good news is that PRINCE2 expects you to be using the particularly powerful ‘product-based’ approach to planning, which starts with identifying and understanding what the project must produce – the products.

Sad to say, those in the PRINCE2 community generally don’t really understand this approach and the associated techniques and the PRINCE2 manual doesn’t now do all that much to help. As a result, people undervalue ‘Product-Led Planning’ to the point of frequently leaving it out. That’s more than tragic, because Product-Based or Product-Led Planning is a very real help. It helps in planning but then also opens the door to effective progress control and quality management, as well as helping significantly with risk management. The full detail on planning is in Chapter 14, including lots to help with using the product techniques.

PRINCE2 expects this same basic product-led approach no matter what level of detail you happen to be planning at the time. You work at three levels of detail through the project: Project, stage and team level.

In the Initiation Stage, you work at the first two of these levels. You produce a Project Plan for the whole project and then a more detailed Stage Plan for the first delivery stage; the one that immediately follows the Initiation Stage.

When you’re doing the project planning, guard against getting sucked down into a mass of detail and effectively start working at a stage planning level of detail. Don’t work too hard here! It’s a big temptation and a common mistake to get very detailed when you should be focusing on the higher-level view of project planning. The danger is that you miss some big, important and even ‘obvious’ things at high level because you’re down on the floor with a microscope. Besides there is usually little point in planning the later bits of the project in a lot of detail because things will almost certainly have changed by the time you get there. You’ll be pleased to know that a neat way exists of enabling you to stick to the right level of detail for each level of plan – yes, it’s another advertisement for Chapter 14 and the full works on planning!

Working on the Business Case

In Start Up, an outline (quick and dirty) Business Case is prepared which helps the Project Board decide whether the project is worth planning in detail. In Initiation, where you’re doing that planning, now is the time to add the detail to the Business Case.

Building the full Business Case

The business justification for the project may need considerable work, or it may be very simple (such as with a compliance project, when you do the project because someone told you to), or anything in between. The Executive is the owner of the Business Case and is primarily responsible for making sure that the right level of detail goes in, although frequently the Project Manager is heavily involved with the research work and the Senior User(s) takes responsibility for identifying the benefits.

As with all the management products in a project, PRINCE2 does not give a format but rather just a list of suggested contents. For the Business Case in particular, you need to check what your own organisation requires. Your corporate management may need you to include particular information in the Business Case, and may even want it to be in a particular format to fit in with organisational approval procedures. Adjust the contents of the PRINCE2 Business Case to meet your organisation’s requirements and preferred layout. You may already have that information to hand if you’ve done a project before, or if you recognised the importance of that Business Case format and procedures when you thought through the Project Approach in Start Up.

Planning the measurement of benefits

Many business benefits won’t be clear until after the end of the project, whereas some others may be clear at the end of it. But particularly in business projects where things may be being taken into operational use at several points during the project, not one ‘big bang’ at the end, benefits may come on stream much earlier than project close down.

To set down exactly when benefits will be visible, when they should be measured, by whom and how, PRINCE2 has a Benefits Review Plan. You prepare this now, as you work on the fully detailed Business Case, but you need to keep it up to date during the project if things change, such as you find some additional benefits that weren’t spotted at the outset.

You can find the full detail of the Benefits Review Plan, along with the Business Case, in Chapter 11.

Preparing for the First Delivery Stage

In line with the PRINCE2 approach of planning a project stage in detail towards the end of the previous stage, you now need to plan in detail for the first delivery stage – the one that comes after Initiation. This is no different from project planning in that it uses the same techniques, but of course you’re working at a lower level of detail.

The end of the Initiation Stage is just like the end of any other project stage, so in PRINCE2 the ‘Managing a Stage Boundary’ process handles this, including the stage planning for that first delivery stage. Have a look at Chapter 6 for the full detail on the Managing a Stage Boundary process and at Chapter 14 for planning, including stage level planning.

Fitting PRINCE2 to the Project

Part of the final work of Initiation – though you may choose to do it a bit earlier in the stage – is to decide how the PRINCE2 method is to be used on this particular project. You need to think this through carefully and you may want to consider some of the advice in Chapter 3, ‘Getting Real Power from PRINCE2’. Put simply, you need to balance your use of PRINCE2 against the characteristics and control needs of the project.

An explanation of how you’re fitting PRINCE2 to the project goes into the Project Initiation Documentation and forms the last section of it. Chapter 2 gives you more on adjusting PRINCE2 to fit the project.

Writing the Extra Bits of the PID

Most of the content of the PID is made up of major products like the Communication Management Strategy, but you need to add in a few additional sections before the PID is complete.

Project definition

The definition section does slightly more than define the project, as the sub-headings indicate. The section also explains the nature of the project.

Background. Information on why the project idea came into being, such as being part of the five-year organisational development strategy.

Project objectives and desired outcomes. Objectives should be agreed, and a good way to get them agreed is to put them into the PID so that they’re clearly stated and then signed off. That’s true of desired outcomes too, but that’s also helped by the Project Product Description (see Chapter 4 for more on that one), which is included in the Project Plan.

Project scope and exclusions. This says clearly what is in, and out, of the project. You can think of exclusions as ‘negative scope’ and specifically stating what the project doesn’t cover can really help with scope clarity. The exclusions help avoid misunderstanding with later disappointment when people don’t get something they had thought was included in the project.

Constraints and assumptions. This sets down any limitations on the project, such as that it must deliver by the end of the financial year. Stating assumptions is also good because if things change, everyone recognises that an adjustment to the project is justified. An example is an assumption that another project on which this one depends will finish on time or no more than four weeks late. If that other project ends up six weeks late, everyone understands that a time impact is now on this project and the plans need to be amended accordingly.

The user and any other known interested parties. This is to show who will be impacted by the project and who may therefore need to be consulted. The main user interests will be represented by a role on the Project Board.

Project Approach

The Project Approach sets down things that affect how the project is run and the nature of the final deliverable. Please see Chapter 4 for more detail as this information is identified during Start Up.

Project team management structure and roles

You can find out more about this in Chapter 12 on roles and responsibilities. But basically this section of the PID is an organisation chart for the project that you’ve put together, or at least begun, in Start Up.

Interfaces

This final part lists interfaces such as with other projects, other organisations or things such as operational or business procedures.

Putting the PID Together

When you put the extra parts listed in the last section together with the main products covered earlier in the chapter you have yourself a PID.

When you take a closer look at the content of the PID, you may think that some of it looks rather like the Project Brief. If so, you’re right. You can see considerable overlap, but remember that these same things are now in much greater detail. For example, the Business Case was an important element of the Project Brief. But in Start Up that Business Case is sketchy and incomplete – an Outline Business Case. By the time you get to the PID, you’ve done a full Business Case possibly including investment appraisal. So yes, the Business Case appears again in the PID, but now complete and in much greater detail.

Looking at How You Use the PID

You can use the PID in three ways in PRINCE2. The first is to define the project in Initiation and to support the decision of the Project Board at the end of the Initiation stage regarding whether to authorise the whole project or to stop after the planning because it doesn’t look worth doing after all. A bit more on this first use of the PID in a moment.

A second way you can use the PID is as an ongoing reference for staff joining the project. This can help particularly in larger projects when lots of staff are coming and going as different parts of the work are done. Giving the PID to new staff to read can save a lot of explanation of individual areas of project control. Potentially, you can give the PID to any of the project staff, but Team Managers find it particularly helpful.

Finally, a very important third use of the PID is to check on the achievement of objectives. The Project Manager uses this information when creating the End Project Report, which in turn informs the Project Board (and possibly a programme or management board) if the project has been successful. For more on this use of the PID during project closure, turn to Chapter 9.

Asking the Project Board to commit to the whole project

The focus of a normal stage boundary is to check whether everything is okay and decide whether or not to continue to the next stage. But the decision at the end of Initiation is rather more important. Here, the board members are being asked if they want to commit to the whole project and then specifically to authorise the start of work on the first delivery stage. Up to now, the Project Board has only committed to planning in more detail – the decision they make at the end of Start Up. The end of the Initiation stage and the production of the PID mark the point where they make the major go/no-go decision for the project. The board might stop the project prematurely if something goes badly wrong or if new conditions mean that it’s no longer needed, but their intention now is to run it through to the end.

Pens are powerful things and most managers in most organisations worldwide really don’t like using them when giving authority – so it’s not just a problem in your organisation! Important documents like the PID and Stage Plans need to be physically signed. Such sign-off encourages clear commitment from the board, reinforces the importance of their responsibility and gives the Project Manager clear authority.