10

Thinking inside the box

Without a box, there is a risk that creative work becomes very splintered and unproductive, roughly like writer's block before one knows what to write about. Not surprisingly, creative people also tend to be very productive, because it is easy for them constantly to produce new solutions since they are clear about the limits.

We have now collected enough information about what creativity is and how it works to answer an earlier question: If creativity is not thinking outside the box, then what is it? The simplest answer, and the one that comes closest to the truth, is that creativity is really about thinking inside the box.

Contrary to what one might think, creative people have very distinct and limited boxes inside their heads – boxes that bring to mind the box in the exercise you did with the dots in Chapter 6. That box had very strong but invisible walls that prevented people from finding solutions outside the area in question. Such a box is really a better metaphor for creative thinking.

Psychological research shows that creative people are fully aware of the walls that confine their thinking. Researchers even go so far as to say that knowing where the walls are is a criterion for achieving a creative result. This explanation works on two levels.

The first level concerns the box as it is usually thought of and as it functions in the expression ‘to think outside the box’. The explanation is related to our earlier definition of the creative result. The second level is based on the knowledge we have discussed about the creative process, and gives a different picture of what the box really is.

On the first, more abstract, level one can say that the totality of knowledge and experience within the field constitutes the box; for example, how one manufactures and markets cars. A creative result implies that one adds something meaningful to the category ‘car’. But for the new product or concept to be meaningful, it must be distinct from whatever already exists in the category on one or more essential points. In order to relate to these points, one must be thoroughly familiar with what is involved in, and what marks the limits of, the category ‘car’, i.e. the walls of the box.

On the second, more concrete level, we can see our own thought patterns as a box. The creative result, as we know, is to do with using a rule or routine to reach an uncertain outcome. The point of the rule or routine is to force the brain to think along new paths and take a different path from the habitual thought tunnel or sunken riverbed. But to succeed in this, it is necessary, firstly, to be aware that we really do have tunnels and riverbeds inside our skulls; and, secondly, to know which paths they take so that we can change direction.

Thinking inside the box has a number of important advantages. One such advantage is that the box focuses thought activity. It works roughly in the same way as giving the monkey a box full of slips of paper containing words to choose from, instead of asking it to go and look for the words. In this way, we avoid waiting those millions of years, which, in the first place, would probably be spent simply finding the appropriate words. (Where would the monkey look, and when would it have finished looking? This is hard enough for us to answer and even harder for the monkey to work out.) The monkey would then start the endless work of word combination.

Without a box, there is a risk that creative work becomes very splintered and unproductive, roughly like writer's block before one knows what to write about: the uncertainty can be paralysing, but as soon as one has a clear idea of the limitations, the writing starts to flow faster than a well-shaken cubic bottle of ketchup. Not surprisingly, creative people also tend to be very productive, because it is easy for them constantly to produce new solutions since they are clear about the limits.

An additional advantage of the box is that it simplifies creative work. When the monkey has finished combining words, the real work starts – interpreting the combinations and developing them into bisociations. Not everyone would make the bisociation ‘tyre change–ditch’ as easily as the fourth friend did in the example earlier in the book (evidently the other friends did not). Because not many of us have had reason to think closely about changing tyres, we have difficulty in making something meaningful out of that combination. If the monkey were to hand us combination after combination of words to which we cannot relate, we would simply fail in the generation of bisociations and the monkey's work would have been in vain. To ensure that the creative process produces a creative result, we must be able to relate to the elements that are included in the process: they must be inside the box.

A third advantage follows naturally from this. Because the box focuses and clarifies, it can also give hints on the direction of development. If we know in advance which words the monkey cannot reach or we cannot interpret, we can make sure they are in the box. We do not have to wait while the monkey searches and fails to find them, or tear our hair when we are defeated by the ‘impossible’ combinations we are given. The box helps us to know our limitations.

There is also an advantage in the word ‘box’, which gives the most important advantage of all. The brain uses thought tunnels and riverbeds because it is lazy and does not want to make unnecessary diversions. And the bigger the map surrounding the tunnels and riverbeds, the longer the diversions can be. The word ‘box’ can reduce the size of our imagined map, allowing us to fool ourselves into believing that our thoughts cannot in fact wander very far in odd directions. A box gives a false sense of security in the form of a metaphor. The brain believes it is thinking routinely, which is what it prefers, and therefore feels safer and works better. An efficient method of getting the brain to think in a new way is to get it to believe the opposite.

This is also true of organizations. The box as a metaphor can increase the acceptance of creative thinking in organizations by illustrating the boundaries of creative work. For an organization, working outside the boundaries is uncertain (‘we have no experience of new fields’) and probably inefficient (‘we can be fast and cheap by doing things in the usual way’).

Shaking the box

Thinking inside the box is the first step in creative thinking. But thinking only really becomes creative when the box is used in the right way – and the right way to use the box is quite simply to shake it.

Various experiments have compared creative people's problem-solving and their understanding of it with that of other people. The problem-solving studied consisted for the most part of IQ tests (which consist of series of numbers and similar problems) or of performing associative tests (which instead comprise a series of concepts, i.e. rows of words instead of numbers). Generally speaking, researchers found that the results of creative people do not differ to any marked degree from those of other people. We have established earlier that the IQs of creative people are not much higher than the average. On the other hand, creative people succeed in solving associative tests considerably better than others. For this reason, associative tests have become a common way of measuring creative capacity, and are creativity's equivalent to the IQ test. When the test subjects' perceptions of the tasks they have been given are compared, it appears, not entirely unexpectedly, that creative people find associative tests much more stimulating than other people.

The researchers also measured the test subjects' sense of time and found that creative people experienced that they had spent more time on their problem-solving. It may seem strange to measure the sense of time in particular, but the explanation is simple. If someone asks you to say when you think exactly a minute has passed, what do you do? You could count silently ‘one thousand and one, one thousand and two, one thousand and three …’ and say stop when you have reached one thousand and sixty. By adding together the different stages of the work (the thousands), the brain can easily judge the passage of time. You behave in a similar way when someone asks you the way to the nearest newsagent: ‘First you go right, then straight on for a bit, up some stairs, a few hundred yards to your left and round the corner – it will take about six minutes.’ The test subjects calculated how long they took to solve their problems in the same way, by adding together the separate parts of their task.

Therefore, the answer the researchers received was that creative people have more elements in their creative work. They shake the box more often.

We have used the monkey with the slips of paper fairly frequently in order to consider various aspects of creativity. Let us instead, for a moment, conjure up the image of a box containing the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. As a child, you might have thought that doing jigsaw puzzles was a bit boring, and instead amused yourself by shaking the box and opening it to see what had happened. In that case, you will certainly remember that the pieces ended up higglety-pigglety, and that some used to get stuck in each other in pairs, or sometimes threes or more. And they formed completely new patterns (which were no doubt on many occasions more stimulating to the imagination than the pattern the pieces made when the jigsaw puzzle was completed as intended). A hand here and a leg there suddenly became a hand–leg animal instead of Donald Duck. If you had already read this book, you could have shown Mummy or Daddy your nice bisociation!

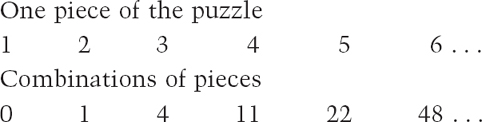

We can now explain why creative people are not particularly fond of IQ tests, while being so good at associative tests: IQ tests are about finding the correct piece of the puzzle, whereas associative tests are about creating combinations of pieces. In an IQ test, the puzzle is as good as finished, apart from a few missing pieces. The easiest way to find the missing pieces is to test them, one by one, against the holes in the puzzle. Shaking the box is an unnecessary waste of time. In an associative test, you must create combinations of several pieces yourself. When you shake the box, the pieces fall into different places and form new combinations. What both tests have in common is that the more skilful you are and the more difficult the problem, the more pieces of the puzzle there are. But while the number of possible solutions in the IQ test increases at a steady pace, in the associative test, the number explodes. Compare the series of numbers below:

When you take out one piece at a time, every new piece requires you to put your hand in the box. When you combine the pieces, the combinations increase exponentially with every new piece. The greater the number of pieces, the more times you can shake the box. And the more times you shake the box, the greater the likelihood that that you will find completely new and meaningful combinations.

As we know, the creative process can be described as following a rule or routine with an uncertain outcome. Shaking the box is the rule of rules, the very essence of the creative process: rearranging the contents time and again and seeing the combinations that arise. In the last part of this book, we will see how the box can be shaken in different ways for creative business innovation.

Expanding the box

In Chapter 9 we asserted that the creative person has a greater flow of ideas than other people. What we meant by this was, firstly, that creative individuals create more combinations of associations, and, secondly, that they make more far-fetched connections. We have already determined that a high number of combinations is a condition for achieving a creative result: creative business innovators both succeed and fail more often than others. But there is also a connection between how far-fetched the combination is and how creative the result is.

Sit down for a moment and make combinations of banking services (loans, savings, credit reports, insurance), risks (long-term, short-term, high-yield, low-yield), and media channels (computers, postal service, telephone, TV). If you have a strong flow of ideas, you should quickly put together quite a lot of combinations from these terms, and in total you can create 64 new products. Then you might well ask a bank whether they think any of the ideas seem interesting. Unfortunately they will probably reply that they already have such a product. All the 64 products are easy to grasp, and it is therefore not surprising if they have already been set up. Banking services, risks and the media lie close to each other in the puzzle box and most people who shake the box just a little will produce known combinations.

A simple rule of thumb is that your first spontaneous solution is not creative – someone else has already thought of it simply because it is within easy reach. Patent lawyers talk about parallel activity, maintaining that many products cannot be patent protected because they are so easy to think of that many people can think of them simultaneously.

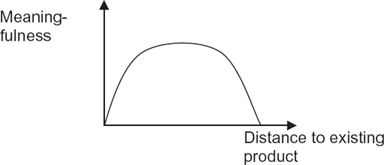

As if it were not enough that solutions that are easy to grasp suffer from being common and far from unique, there is also a risk that they will not be particularly meaningful. Figure 10.1 shows the connections found in two American studies between, on the one hand, the distance from a new concept to existing products on the market, and, on the other, perceived meaningfulness. The first study analysed creative marketing concepts in 34 consumer goods companies with a total range from pharmaceuticals to biscuits to storage products. The other study included interviews with more than 400 consumers who had been eager to adopt new marketing concepts. In both studies it was found, not unexpectedly, that concepts that were too distant from what was already on the market were not very successful, because people could not relate to them or see the point of them. We will devote more space to the importance of reducing the perceived distance for the new solution later in the book.

However, a somewhat more surprising result emerged from the studies – namely, that concepts that came too close to existing products were also perceived as less meaningful. The psychological explanation is very simple. People think, consciously or unconsciously, in the same way as the patent lawyers we have just mentioned: ‘This solution is so obvious that anybody might have marketed it a long time ago.’ And the conclusion is that if no one has used such an obvious idea before, then it is presumably not worth having.

Let us return to the exercise with the banks and, instead, try to combine daily routines (for example, eating or travelling, which most people do several times a day) with banking services. This was done in the USA, resulting in drive-thru banks for cash errands, and in Shanghai, where lunchtime banks were started for financial advice. Both concepts have been successful: they have attracted customers and brought something to the market.

Drive-thru banks save time because they are on the route between home and work; they are convenient, which appeals to Americans; and they have been increasingly perceived as more secure as the number of attacks at automatic teller machines has grown. The lunchtime banks have saved time because many people do their bank errands during the lunch break. They have also created a friendlier atmosphere, which is important in the relationship between the adviser and the advised. The concepts have been meaningful by relating to what is already on the market and what people are used to. They were not too easy to think of, or obvious in any way.

Banking services and daily routines are pieces of the puzzle that do not lie close to each other in the box. If the box is small, then we would probably not get these pieces to cling to each other when we shook the box. Nor would there be enough space to enable each piece to move sufficiently far from any other piece. We must therefore expand the box in order to make more far-fetched connections. In the psychological study of subjects' solutions to IQ tests and associative tests, it was found that creative thinking, i.e. the combination of different associations, takes up more space in our heads. What we mean by ‘more space’ is that a larger amount of brain capacity is used and more memory functions are activated. In concrete terms, this could be illustrated in the same way as you may have seen the effect of a gym machine being illustrated – by using pictures and colouring the activated parts of the body red: creative thinking requires us to expand the red areas in our heads. To return to our old friend Albert Einstein, we can note that he not only had an unusually small and dense brain, but tests of his brain have demonstrated that he had the capacity to use unusually large areas of it simultaneously. Computer tomography (CT) scans of Einstein's brain beside an ordinary brain in fact bring to mind large and small boxes.

Large and small boxes explain an apparent paradox: while creative people have a great deal of knowledge and experience in their fields, many people in fact seem to be limited in their thinking by what they have previously learned or done. The more we learn, the more pieces of the puzzle there are in the box and the more combinations we are able to make.

But the more pieces there are in the box, the greater also is the congestion. So the box must also grow if we are to get any satisfaction from all the pieces. For just as a big box is meaningless if it only contains a few pieces, you will get nothing from the pieces you have collected if they are squeezed into a little box that lacks the extra space required. In the next part of this book, we will work with exercises aimed at expanding the box in different ways, so that we have more room to shake out combinations of more widely disparate pieces of the puzzle.

Filling the box

Turn back a few pages and have another look at the number series that represents how the possible combinations of pieces of the puzzle increase for each new piece you put in the box. It speaks for itself. The small effort that is needed to fill the box with another association or bit of knowledge is repaid many times over when you later shake the box. Knowing a little more, in other words, makes you much more creative.

There is really no such thing as useless knowledge – there are no pieces of the puzzle or slips of paper that are inappropriate to put in the box. We have already shown that the perception of knowledge as constraining is really a question of the box being too small. When it has been expanded, you can continue to fill it with new pieces and in this way increase the number of possible combinations. But to make the combinations into bisociations, you must find meaning – i.e. a business proposition that is worth marketing.

The three first questions in the book's introductory test (see page 20) provide a clue that even though there are no pieces that are ‘wrong’, there are certain pieces that are particularly ‘right’. In order to obtain a really high score in the test of your potential as a successful business innovator, you must have a thorough knowledge of people in the form of their behaviour, drives, demography and trends, and you must be knowledgeable about economics and business. There is nothing odd about that. At the end of the day, all bisociations must be used by people and must therefore be attuned to their wants, needs and behaviour, and if they are to be profitable, they must be realized in an economically viable and effective way.

Therefore, there is no knowledge that is wrong or useless. Insights into quantum physics, termite hills, plumbing, poker, tailoring and cooking can all be invaluable and create new, exciting combinations. The more you know and learn, the better. But if the combinations are to be turned into creative business opportunities, they must be interpreted in connection with an extra piece of the puzzle that has to do with people and business. Otherwise, you will be no more than a monkey combining words.

Take, for example, the unsuccessful launch of the superior Dvorak keyboard layout, which was thoroughly trounced by the established QWERTY system that we all still use. If the marketers had considered a fundamental fact about human beings, namely that we are lazy, then a warning light would immediately have started to flash. It was difficult enough to learn to use a keyboard layout the first time, so how likely are we to think it worth learning another? It is in fact much simpler to continue using the old system, which is what we have done. If we then add to this a fundamental economic insight about the economics of scale, then there should have been both flashing lights and sirens. The QWERTY system now has an exponential advantage over any newcomer: for every new Dvorak keyboard there exist many more QWERTY keyboards. To succeed, Dvorak must therefore be produced and sold at a much greater rate in order to establish itself. (But who would bother to write with two different systems in parallel, which would be unavoidable as long as the QWERTY keyboard layout was installed in the majority of typewriters and computers that people use?)

Knowledge about people and business can also explain why Internet retail did not take off at the explosive rate that everyone at one time predicted. Another fundamental quality of human beings is that we are cowards: we do not like to take risks. This insight is at the root of all banking and insurance services and explains why brands are so important – they minimize the risk because we feel that we know what we are getting instead of taking a chance with the purchase of an unknown product. So think about what happens when we buy products from the other side of the world via a computer, or, for that matter, groceries from the shop round the corner. When we cannot actually handle the product, how can we be sure of what we are getting? Can one trust a company that is far away, or really rely on the local grocer to pick out the best bananas? People will probably want to pay a lower price as compensation for the risk (which is exactly how financial services work and why well-known brands can charge higher prices) and furthermore preferably pay only when they have the product in their hands. With a little knowledge of economics, it is easy to see that it is a difficult business – deep pockets are required, firstly, to lay out the money and, secondly, to get a lower price for the product sold, combined with the necessary investment in distribution (at best digital and computerized – at worst physical transport), and in addition there will be a fairly long period of time before the business turns a profit. And this is precisely how things turned out – many companies ended up going bankrupt around the Internet-obsessed turn of the millennium.

A third fundamental insight about people is that we are stupid. We do not have the capacity or the energy to learn and comprehend all the features of different products. This explains why product novelty had such a minor effect in the model we looked at more closely in the section on the creative result (see Chapter 7). People do not care too much about a product's new features. It is more a question of whether the new features are expressed in a meaningful way and whether the impressions they make are easy to understand, which explains why marketing becomes so important. With this insight in mind, we can understand why Ericsson lost ground for so many years in the mobile phone market: people did not understand the product's superior technical qualities (if indeed they were superior, which few of us can judge). We can also understand Sony Ericsson's fairytale surge in the market when the superior qualities began to be packaged and communicated in a meaningful way. The mere name Sony Ericsson is a smart brand bisociation that people understand and like.

Insights about demography and trends are also important pieces of the puzzle that can be constantly added and generate completely new and unique combinations. The USB memory stick is an example of a bisociation (or rather trisociation) of increased memory compression, demographic development towards the use of different computers in different places, and trends favouring technology as accessories (e.g. MP3 players). The electric car is another bisociation based on demography in the form of single households, increased traffic and congestion charges, combined with a trend towards increased environmental awareness. Car tolls in major cities are in other respects a demographic feature that can be combined into a large number of bisociations in the transport and services sectors.

We have now observed some schematized examples of knowledge of human qualities, demography and trends, and also economics and business. They might appear unnecessarily oversimplified and generalized and, to a certain extent, this is of course true, but it is important to remember that people and businesses are in fact fairly simple and predictable. People function in much the same way whether we buy soft drinks or motorbikes – the similarities are much greater than the differences, irrespective of the product category. And the laws of economics are the same whether you are selling oven gloves or caravans. This means that these pieces fit every puzzle and that it is in fact these pieces that distinguish combinations of words from business-oriented bisociations. That is why questions about people and economics and business make up the first three questions in the test of your potential as a successful business innovator.

After reading Part IV of the book, you will be able to improve your score on the test as you will have filled the box with fundamental new knowledge about how people view product categories and react to novelty, and about the business-oriented aspects of our behaviour.