18

The power in brands

To make life easier and avoid thinking more than necessary, we usually try to let past experience be our guide. Brands automatically bring to mind thoughts and ideas and stimulate behaviours in us. This has enormous potential for the development of new products and new marketing concepts.

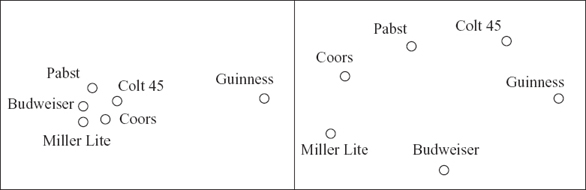

Just as our choices and our thinking around product categories and products tend to follow riverbeds and thought tunnels, our thoughts about brands are similarly locked into certain patterns. This means that the brand automatically elicits certain thoughts and behaviours in us, which is termed brand gravity. Figure 18.1 is a classic example that you will doubtless recognize.

The diagram shows the results of an American consumer study comparing people's taste experiences of different beer brands when they knew/didn't know which brands they were tasting. The left-hand box shows how people rated the taste of the different brands of beer when they didn't know which brand they were tasting. Not entirely unexpectedly, the brands came very close to each other (with the exception of the Irish beer Guinness, which has a very distinctive taste). This is the typical result for most product categories; the actual differences in the product are small among competitors. The right-hand box shows how people rated the taste of the different brands of beer when they knew which brand they were tasting. As you can see, the differences are much greater and the distribution is wider. The reason is that the brands have fixed people's thought patterns to such a degree that they perceive whole new and different tastes in the beer!

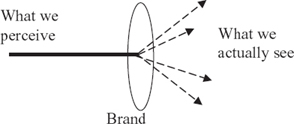

The link between the brand and its various manifestations in the form of the product or products, advertising and other communications, as well as people's contacts with the company (for example, sales staff or customer service) is often illustrated by the following arrow:

Logic would tell us that people create a picture of the brand as a result of their contacts with its various manifestations: we are coloured by our perceptions of the product, of the advertising and all other contexts in which we come into contact with the brand. This logic holds for new brands of which people cannot and do not have any prior experience. But when it comes to established brands (which comprise the vast majority of all brands and products with which we come into contact), this logic does not hold. Instead people exhibit a reverse logic:

![]()

To make life easier and avoid thinking more than necessary, we usually try to let past experience guide our decisions and our responses. Instead of evaluating, forming an opinion about and adapting our behaviour to products with which we come into contact, we attempt to fit them to existing thought patterns. Brands create such fixed patterns in the form of what are referred to as branch schemas. The brand schema consists of a number of riverbeds, or paths, that our thoughts follow when we come into contact with the brand.

In experiments with local brands of beer, we tested how people reacted to actual (real) slogans and our own made-up slogans for the different brands. We found that it made no difference which type of slogan was used for a well-known brand; because how people evaluated the brand was already firmly fixed in their minds. On the other hand, there was a big difference in how people evaluated the different types of slogan depending on which brands people believed they came from. The same slogan was rated highly when people thought that it belonged to a brand they liked, and poorly when they instead associated it with a brand they didn't like. In addition, people perceived our made-up slogans as familiar (‘yes, I recognize this’ or ‘sounds familiar’) when they were told that it came from a brand they usually purchased, but experienced a known (real) slogan as new and unfamiliar when they were told that it was from a brand they didn't normally purchase. This experiment is a clear indication of how the brand schema creates a false sense of certainty when evaluating manifestations of the brand. As people already have a preconceived notion of the brand to which they fit their actual responses when they come into contact with it, they will like or dislike the same slogan, and recognize it or not recognize it, depending on whether they believe that it belongs to a brand they like or one they don't like.

In another experiment, we analysed how the brand schema affects what people read into the advertising for a product, and the product itself. We used a brand of soft drink not found on the local market so that people could not have developed a brand schema for it. We then manipulated the content of their brand schemas for this soft drink by manipulating the data in a taste test published in a daily newspaper. The soft drink was part of a test of several new soft drinks to be launched in the summer. In one edition of the test, we added in the words ‘sophisticated’ and ‘elegant’, while in another edition we described it instead with the words ‘thrilling’ and ‘young’. People had no idea that we had added ‘our’ soft drink to the list of brands, or that it had been charged with particular words. The idea was that these words would slip into their minds and form a brand schema for the unknown soft drink. Later, the subjects were shown an advertisement for the unknown brand and a can of the drink. Although all subjects were shown the same advert, one group of subjects were more likely to describe the advert as ‘sophisticated’ and ‘elegant’, while the other group were more likely to describe it using the words ‘thrilling’ and ‘young’. Compared to those in the second group, people in the first group also thought that the can appeared to be somewhat smaller (contained less soft drink) and that the drink would probably be less carbonated. The experiment shows how quickly and easily a brand schema can be established and how directly it impacts our reactions and judgements.

A brand schema can perhaps be most simply described as a kind of lens, as in Figure 18.2. A lens collects our visual impressions so that they appear to come from a particular point even when, in fact, they do not. This is similar to the way the surface of a body of water refracts light so that things beneath the surface appear to be located elsewhere than they actually are. Similarly, the effect of the brand schema is that we can be exposed to an extensive range of widely differing manifestations of the brand and still form a clear and consistent perception of it, based on the pathways already formed in our brains.

The brand schema creates an extraordinary pull in the brand that draws all the various parts of the business and the product's various manifestations in a specific direction, in the same way as gravity draws us to the Earth and keeps the Moon in the same orbit around the Earth. The fact of brand gravity means that there is enormous flexibility for the development of new products and concepts once the brand is established, because for the most part they simply cannot go wrong. Just as you can jump from a tree, off a cliff or out of a plane and always land below, product development and marketing concepts may manifest in a variety of ways and still touch down in the brand.

We tested brand gravity in an experiment where people were asked to respond to a number of brand extensions from the category ‘non-car-bonated soft drink’. We selected the product that people thought would be the worst possible idea for a non-carbonated soft drink brand to launch, which turned out to be cottage cheese. In the eyes of the subjects, cottage cheese just didn't fit with the products of a manufacturer of a non-carbonated soft drinks. We therefore produced an advert and packaging for a new type of cottage cheese, using a known brand of non-carbonated soft drink with strong brand gravity, and a relatively unknown brand without brand gravity. The results were very clear. Those people who came into contact with the product launch under the unknown brand were not particularly inspired to try the cottage cheese and had a very sceptical attitude to the product and the brand. Those who had come into contact with the product under the well-known brand were much more curious and eager to try the cottage cheese. When we asked them to free-associate around the brand and the new product, we could see a clear gravitational pull when the subjects were made aware of those aspects of the cottage cheese that could be associated in any way to the known brand (for example, healthy, natural, fresh), while no attempts were made to make them aware of other aspects of cottage cheese that did not fit with the brand (everything from its creamy texture to associations such as ‘gourmet’ or ‘snobbery’). It was interesting to note that brand gravity even rekindled interest in the known brand's core product of non-carbonated soft drink. Those people who were exposed to the launch of the cottage cheese under the known brand were also more eager to consume the soft drink.

An important lesson from this experiment is that brand gravity results in an enormous potential for the development of new products and marketing concepts.

Firstly, brand gravity is the antithesis of the conventional picture of the brand as some kind of straitjacket that limits the company's products. Instead of locking the company into a certain business or perception among consumers, the brand opens up virtually limitless possibilities for new business creation because brand gravity makes new products and marketing concepts credible and assists people to understand them. An interesting observation in the non-carbonated soft drink experiment was that when we were looking for the ‘wrong’ product to launch, it was much harder for people to find fault with the products we suggested if those we asked were also told that it wasn't just ‘a brand’ of non-carbonated soft drink that would be launching the product, but the particular, well-known brand. They then immediately began to introduce characteristics to the products and create associations that were not there just to fit them into the brand schema of the known brand in their own minds.

Secondly, brand gravity minimizes the risk in launching new products or marketing concepts. The brand perception is transmitted to these new manifestations of the brand. Unless people have some real reason for being suspicious of the new product because it is tangibly and obviously a failure (which few products are these days), they will be inclined to judge it positively. While it is not certain that the product will be successful in the long term, it is relatively easy to get people to try it, which gives it a very comfortable send-off.

A third aspect of brand gravity is that it maximizes the ratio between the creative result and innovative thinking. By this I mean that you don't need to think in particularly novel ways and develop a lot that is actually new in the product itself or the marketing concept in order to achieve a sizeable creative result. As we discovered previously, the creative result requires something that is meaningful as well as novel, and brand gravity is clearly a powerful generator of meaning. Launching a new soft drink or a new airline of the regular kind is not particularly creative. But doing so under the brand ‘Virgin’ is very meaningful. This adds whole new sets of values to an established product category. In this way, you can change people's view of the product category and thus also the rules of the game for all the various players. And by doing so, stretch out the boundaries of rigid markets and break through market ceilings.

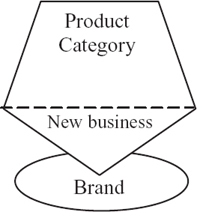

Figure 18.3 illustrates how the gravity exerted by a known brand can stretch the boundaries of an established product category and pull it in a completely new direction. As a result, opportunities for new business arise for both the brand in question and for other brands. One way of making use of short-term and long-term brand gravity is precisely to use both the known brand and other brands. The known brand pulls the product category in one direction and creates interest in the short-term in the new product. Then the company uses a new brand for their business in the long term. For a variety of reasons, the company might not want to invest too much money in a new product category under the existing brand. For example, a long-term investment will eventually change the brand schema as people slowly but surely (because it does take quite some time) add new experiences and contacts and revise their mental picture of what the brand stands for. Or the company might not want to risk a flop under the existing brand in case it has a negative impact on the brand. (As we have seen previously, new products launched under known brands get a propitious start. But, like any product, their survival is not guaranteed after the introductory phase if they do not represent a sufficiently attractive offer to consumers.) The risk of the perception of the company being coloured negatively is not greatest among consumers. In Chapter 5, we mentioned the Florence Nightingale effect, which shows that people don't necessarily think less of a brand because the company launches an unsuccessful product but paradoxically may, in fact, like the company better for it. Instead, the risk lies in business partners and distributors being reluctant and less willing to participate in future business with the brand (a clear example of how important knowledge of business is to add to the other areas of knowledge discussed in this book).

To return to the reasoning presented in Chapters 7 and 8 about the creative result and the creative process, we can say that brand gravity creates new bisociations in existing product categories. By using the brand as a lens, you can perceive these bisociations and see business opportunities in a category that no one has previously seen or grasped. A known brand can generate sufficient gravity to pull the product category in a new direction, but to discover any new inroad to the market is a huge step towards generating new business. In actual fact, you can go a long way by using any existing brand as the lens through which to look at existing product categories in order to perceive new directions in which they can be taken.