Chapter 8

How Investment Firms are Regulated

8.1 INTRODUCTION

In all major economies, firms that play a part in the investment process have their activities monitored by one or more regulators. Regulators should not be confused with central banks, although in some countries the regulator and the central bank may be the same organisation. The precise way in which firms are regulated differs from country to country, although within the European Union, most regulations are harmonised. At a global level, regulators and central banks meet in supranational bodies such as the Basel Committee, which harmonises some aspects of regulation from a global perspective.

From an IT perspective, within the business applications used by investment firms, there are a number of functions that behave in the way they do because regulatory requirements have been built into their design. This matter is discussed further in section 8.3.6.

This chapter provides a brief overview of regulation from a global perspective, and then focuses on the main aspects of European, and then United Kingdom, regulation. Note that some authorities (such as the BIS – see section 8.3.1) refer to regulation as “supervision”, and in this chapter the two terms have the same meaning unless otherwise stated.

8.2 OBJECTIVES OF REGULATION

The objectives of financial regulation can be summarised by looking at those of the UK regulator, the Financial Services Authority (FSA). The FSA’s four specific and equal objectives are:

- Maintaining market confidence

- Promoting public understanding of the financial system

- Securing the appropriate level of protection for consumers

- Reducing financial crime.

While other countries’ regulators might express their objective using a different form of words, the FSA’s objectives are typical of the objectives of regulators worldwide.

The Bank of England is the UK’s central bank. It has two core objectives:

- Monetary stability, defined as stable prices and confidence in the currency. Stable prices are defined by the government’s inflation target, which the Bank seeks to meet through the decisions on interest rates taken by the monetary policy.

- Financial stability, which entails detecting and reducing threats to the financial system as a whole. Such threats are detected through the Bank’s surveillance and market intelligence functions. They are reduced by strengthening infrastructure, and by financial and other operations, at home and abroad, including, in exceptional circumstances, by acting as the lender of last resort.

There is obviously considerable overlap between the Bank’s objective of financial stability and the FSA’s four objectives, but it is the work of regulators – not central banks – that we are concerned with in this chapter.

8.3 THE GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE

Virtually every country that has functioning financial markets has appointed regulators. There may be a single regulator (the UK model) or several regulators. For example, in the United States some banks are regulated by the Comptroller of the Currency (a department of the federal government), while other banks are regulated by individual states; securities firms are regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), while trading in listed futures and options is regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC).

8.3.1 The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the Basel Accord

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) is an international organisation of central banks, based in the Swiss city of Basel. One of its objectives is to act as “a forum for discussion and decision-making among central banks and within the international financial and supervisory community”.

To this end, the BIS formed the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in 1974. In 1988 this committee developed a unified set of minimum adequacy requirements (known as the Basel Accord) that central banks and regulators in participating countries agreed to implement. A second version of the Basel Accord (known as Basel II) was agreed by the committee in 2004, and is being implemented in over 100 countries at the time of writing.

Basel II has three “pillars”:

1. Minimum capital requirements for all BIS members

2. Common approaches to the supervision of banks

3. Common approaches to market discipline.

This chapter is concerned with Pillar 1 – Minimum capital requirements. Regulators require that banks and other investment firms set aside an amount of their own capital to guard against three types of risk – credit risk, market risk and operational risk. Firms can only lend or invest a given multiple of this capital requirement. The Basel Accord sets out the rules for calculating this capital requirement.

The following paragraphs define these three risk categories in more detail.

Credit risk

Credit risk is the risk associated with one party not fulfilling its contractual obligations at a specific future date. Examples of credit risk include the possibility that a trading party might not have the funds to settle a trade in any kind of instrument, or that a securities issuer may be unable to pay dividends, coupons or redemption proceeds. Credit risk is covered by both Basel I and Basel II.

There are a number of commonly used ways in which an investment firm attempts to protect itself against credit risk, including:

1. Trading party research: Making credit checks about actual and potential trading parties.

2. Use of central counterparties: When trading on order-driven markets, the identity of the actual counterparty is unknown, and all trades are novated by a CCP. The CCP in turn has the highest credit rating, and its creditworthiness is particularly closely monitored by the national regulator because the CCP’s activities are critical to the stability of the financial markets.

3. Requesting parties to provide collateral for certain transactions: This topic is dealt with at length in Chapters 19 to 21.

4. Settling trades on a delivery versus payment (DvP) basis: DvP is the simultaneous delivery of securities by a seller and payment of sale proceeds by a purchaser of securities on settlement date. Both parties instruct their settlement agent to deliver or receive on a DvP basis. If the seller does not have the securities, and/or the buyer does not have the cash, then the agent will not settle the trade.

The various forms of credit risk are examined in more detail in Chapter 24.

Market risk

Market risk is the risk that the value of the investments owned by the investor might decline. There are a number of reasons why this may occur, including:

1. There is a general fall in prices of most classes of instrument caused by global economic or political uncertainty.

2. There is a fall in prices of shares issued by companies in a particular industry, which can be caused by either a poor economic outlook for that particular industry or a fall in prices of shares listed in a particular country because of economic or political uncertainty in that country.

3. There is a rise in interest rates for a particular currency (or indeed all currencies). This would cause a fall in bond prices, because for fixed income securities, market risk is closely tied to interest rate risk – as interest rates rise, prices decline and vice versa.

4. A fall in the exchange rate of a particular currency would cause a fall in the value of investments held in that currency when they were held by overseas investors who value in a different currency.

The various forms of market risk are examined in more detail in Chapter 24. Market risk is covered by both Basel I and Basel II. There are two commonly used ways in which an investment firm attempts to protect itself against market risk, including:

1. Diversification, which is simply defined as “not putting all your eggs in one basket” and means spreading the investment portfolio across a wide range of industries and/or countries. This protects against the possibilities of losses due to poor performance in a particular sector or country.

2. Hedging, which is the purchase or sale of one financial instrument (usually but not necessarily a derivative such as a future or option) for the purpose of offsetting the profit or loss of another security or investment. Thus, any loss on the original investment will be hedged, or offset, by a corresponding profit from the hedging instrument.

Operational risk

Operational risk was introduced in Basel II. It is defined as the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems, or from external events. Basel II defines the following “operational risk events”:

- Internal fraud: Misappropriation of assets, tax evasion, intentional mismarking of positions, bribery

- External fraud: Theft of information, hacking damage, third-party theft and forgery

- Employment practices and workplace safety: Discrimination, workers’ compensation, employee health and safety

- Clients, products and business practice: Market manipulation, antitrust, improper trade, product defects, fiduciary breaches, account churning

- Damage to physical assets: Natural disasters, terrorism, vandalism

- Business disruption and systems failures: Utility disruptions, software failures, hardware failures

- Execution, delivery and process management: Data entry errors, accounting errors, failed mandatory reporting, negligent loss of client assets.

This is of course a very broad, sweeping list of potential problems that could cause an investment firm to lose considerable sums of money. Chapters 25 to 27 will discuss some of the risk mitigation techniques that should be used.

Basel II capital calculations for operational risk

Basel II has approved three methods of capital calculation for operational risk:

- The basic indicator approach: Simply, a percentage of the annual revenue of the financial institution needs to be set aside to cover operational risk. It is expected that smaller firms with a simple business model will adopt this approach.

- The standardised approach: Based on annual revenue of each of the broad business lines of the financial institution. This approach is more refined than the basic indicator approach because it divides a firm’s activities into a number of standardised business lines, allowing different risk profiles to be allocated to each. This is intended to provide a more representative reflection of an organisation’s overall operational risk. Like the basic indicator approach, it uses gross income as a broad indicator, but applies different percentages of annual income to reflect the assumed riskiness of each business. In order to qualify to use this approach, a firm must convince its regulator that it has the necessary management structure, expertise and systems to meet the measure and control its operational risk.

- The advanced measurement approach: Which is based on the firm’s internally developed risk measurement framework adhering to the standards prescribed by the regulations. In order to qualify to use the advanced measurement approach the regulators require banks to comply with more stringent criteria than the standardised approach. They list generic, qualitative and quantitative criteria aimed at ensuring that the bank has satisfactory risk management processes, risk measurement systems and risk infrastructure in place to be able to use the AMA. In particular, firms that want to use this approach are required to calculate Value-at-Risk (VaR), which is examined in section 24.1.6.

8.4 THE EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE

All investment firms in the European Union (EU) are covered by rules issued by national governments and national regulators under the provisions of two EU directives – the Capital Adequacy Directive (CAD) and the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID).

8.4.1 The European Capital Adequacy Directive (CAD)

The first EU-wide Capital Adequacy Directive (known as the Solvency Directive) was issued in 1989. Since then there have been a number of refinements, the latest of which came into force in 2006, although implementation by firms in the member states was not mandatory until 2007. Basically, the CAD is based on Basel II with some modifications.

It applies to all firms in the European Economic Area (the 27 EU states plus Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein). The three states that are outside the EU itself play no part in formulating the directive, but they have agreed to implement it.

The EU’s interpretation of Basel’s standardised approach is that it does not require institutions to provide their own estimates of risks. It nonetheless incorporates enhanced risk sensitivity by permitting the use of, for example, external ratings of rating agencies and export credit agencies. It also permits the recognition of a considerably expanded range of collateral, guarantees and other “risk mitigants”. It includes reduced capital charges for retail lending (6% as compared with 8% in the previous version of CAD) and residential mortgage lending (2.8% as compared with 4% previously).

The EU has renamed Basel’s “Advanced Measurement Approach” as the “Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) Approach”. This allows institutions to provide their own “risk inputs” – probability of default, loss estimates, etc. – in the calculation of capital requirements. The calculation of these inputs is subject to a strict set of operational requirements to ensure that they are robust and reliable. They are incorporated into a “capital requirement formula” which produces a capital charge for each loan or other exposure that the institution makes. The formula is designed to achieve a high level of soundness of the institution in the event of economic difficulties.

The IRB approach comes in two modes. The “Advanced” mode allows institutions to use their own estimates of all relevant risk inputs. This approach is likely to be chosen by the biggest and most sophisticated institutions.

The “Foundation Approach” requires institutions to provide only the “probability of default” risk input. This will enable a large number of less complex banks to reap the benefits of the risk sensitivity provided by the IRB approach.

Every month, investment firms have to produce a capital adequacy statement for their national regulator. Many firms will have built or purchased a dedicated regulatory accounting system (as shown in Figure 7.3) to fulfil this function.

8.4.2 The Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID)

The MiFID was enacted in 2004 and came into force on 1 November 2007, replacing the previous Investment Services Directive that was introduced in 1995. The legislation is detailed, prescriptive and wide ranging – MiFID’s physical presence is twice the size of any of its predecessors. MiFID applies to all firms in the European Economic Area (the 27 EU states plus Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein) and is concerned primarily with:

- Authorisation of investment firms

- Classification of clients

- Conflicts of interest

- Handling of client money

- Handling of client orders, including pre-trade and post-trade transparency.

Authorisation of investment firms

A firm that has its head office in one EEA state and branches in others will be regulated by the national regulator of the state in which its head office is located. As a result, a UK firm with a branch in France would have its French activities monitored by the FSA, and not by the French regulator.

Classification of clients

MiFID requires that each trading party be classified as one of the following:

1. Eligible counterparty – e.g. another regulated bank or stock exchange member firm

2. Professional client – e.g. a pension fund

3. Retail client – e.g. a private individual.

These points have increasing levels of protection. Clear procedures must be in place to classify clients and assess their suitability for each type of investment product, the appropriateness of any investment advice given or suitability of any transaction suggested to them.

Conflicts of interest

MiFID recognises that conflicts of interest may occur when an investment firm may, for example:

- Be acting for both investors in and issuers of the same security at the same time

- Be acting for more than one investor that has an interest in a particular security

- Be acting for investors that have an interest in a particular security at the same time that the firm itself has an interest in the same security.

MiFID requires firms to have a conflicts management policy which requires them to:

1. Take steps to prevent conflicts of interest giving rise to the material risk of damaging clients’ interest

2. Proactively identify business areas where conflicts are likely to arise

3. Document each potential conflict and describe how its affect should be mitigated

4. Disclose its policy to clients on request.

Handling of client money and client assets

MiFID rules include a general requirement to make adequate arrangements to safeguard clients’ money and client assets such as securities that the firm may hold on their behalf. There are specific rules about record keeping, segregation and reconciliation.

Handling of client orders and trade execution

Terminology

This is by far the most complex area of MiFID. It imposes different rules on different types of industry participant. It introduces two new terms that were not in common use before MiFID:

- Multilateral trading facility (MTF), which is a system that brings together multiple parties (e.g. retail investors or other investment firms) that are interested in buying and selling financial instruments and enables them to do so. These systems can be crossing networks or matching engines which are operated by an investment firm or a market operator. Instruments may include shares, bonds and derivatives. An investment exchange is a form of MTF.

- Systematic internaliser (SI), which is a firm, which on a frequent and systematic basis, deals on its own account by executing client orders that are outside the scope of any “multilateral trading facility” (MTF) or exchange.

MiFID requirements

Pre-trade transparency Investment exchanges, other multilateral trading facilities and systematic internalisers that operate continuous order-matching systems must make aggregated order information available at the five best price levels on the buy and sell side.

For quote-driven markets, the best bids and offers of all market makers must be made available. MiFID establishes minimum standards of pre-trade transparency for shares traded on regulated markets and MTFs.

MiFID also obliges an investment firm that is a “systematic internaliser” to undertake what is effectively a public market-making obligation. That is, the firm must provide a definite bid and offer quotes in liquid shares for orders below “standard market size”.

Post-trade transparency Investment exchanges and MTFs must publish the details of all trades executed in their systems. The exact detail of what information is to be published is left to the regulator of the country concerned.

Additionally, investment firms must publish details of trades in relevant instruments executed in the OTC markets.

Publication must be close to real time, and in any event within three minutes of trade execution. Exceptions are made for transactions taking place outside of a venue’s normal trading hours, when publication must be made prior to the start of the next trading day. The full text of the rule about the timeliness of publication states

Information which is required to be made available as close to real time as possible should be made available as close to instantaneously as technically possible, assuming a reasonable level of efficiency and of expenditure on systems on the part of the person concerned. The information should only be published close to the three minute maximum limit in exceptional cases where the systems available do not allow for a publication in a shorter period of time.

National regulators receive all the published post-trade details from all the publishers within their jurisdiction and enter them into a database that they use to monitor market abuse and insider dealing.

Best execution Because of the complexity of the MiFID rules about best execution, this section is broken down into two subsections. The first explains the principles of best execution; the second describes the MiFID requirements.

The principles of best execution, timely execution and customer order priority Broadly speaking, best execution places an obligation on the sell-side firm to get the lowest available price for its customer when the customer is buying, and the highest available price when the customer is selling. If a financial instrument is only quoted on one investment exchange, and that exchange trades it on a quote-driven system, then this obligation is usually fulfilled simply by placing an order on the order queue. The exchange’s own systems will then match it with an opposite order appropriately.

Timely execution gives the firm an obligation to select the most opportune time to execute the order.

If a financial instrument is only quoted on one investment exchange, and that exchange trades it on a quote-driven system, then the best execution obligation is usually fulfilled simply by placing an order on the order queue. The exchange’s own systems will then match it with an opposite order appropriately.

There are situations, however, where the sell-side firm needs to take more care and skill in handling the order. For example:

1. When the order is above normal market size: If the order is to buy or sell a very large amount of stock, then simply placing the entire order on the order queue in one operation will have the affect of moving the price adversely. In such a situation the sell-side firm has two alternatives:

- It could split the order up into smaller parcels and feed it on to the order book over a few days. This may, however, conflict with its obligation to provide timely execution.

- It could (if the order was to sell) purchase the stock from the investor as a principal transaction, and dispose of the stock that it now owns over a few days. If it does this it needs to be able to prove that the price it charged the investor was not lower than the prevailing order book price at the time. If the order was to buy, then it could sell the stock to the investor as a principal transaction, and purchase the stock that it is now obliged to deliver over a few days. If it does this it needs to be able to prove that the price it charged the investor was not higher than the prevailing order book price – in other words that it has in fact achieved best execution.

2. When the instrument is quoted on more than one exchange: The shares of large multinational companies are often quoted on many stock exchanges. The main market for Sony Corporation shares, for example, is the Tokyo Stock Exchange (where Sony shares are priced in JPY), but Sony shares are also quoted on the LSE (both in JPY and GBP), the New York Stock Exchange (in USD) and the Deutsche Borse (in EUR). In such a case, a sell-side firm that has access to all of these exchanges should research the prevailing price levels on all of them to establish the most favourable price for the client. However, the two parties have also to take into account some other factors when deciding which exchange to route the order to:

- Tokyo is the main market where most of the trades take place. There might be less liquidity in the other markets, meaning that the order might take longer to fill.

- On the other hand, say that the investor is located in the USA, and has requested execution today. By the start of the working day in the USA, the Tokyo market has already closed, and therefore execution today is not possible. The NYSE will be open, and the European exchanges may also still be open.

- The customer might want to pay for Sony shares in JPY. Because the Deutsche Borse prices Sony shares in EUR and the NYSE prices them in USD, there would be additional foreign exchange transaction costs in trading in New York or Frankfurt.

- It is possible that the sell-side firm that receives the order is not, itself, a member of the exchange that is offering the best price and the most liquid market. For example, not all London-based firms are members of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. If this is the case, then the London firm might have to use another broker in Tokyo to place the order on its behalf. This would involve two lots of brokers’ commission, and this could invalidate the price advantage if it was very slight to begin with.

The above examples show that there can be a practical conflict between “timely execution” and “execution at the best price”.

The final rule that the sell-side firm needs to take into account is customer order priority. The firm is obliged to execute customer orders and own account orders fairly and in due turn. This rule exists because of the possibilities of conflict of interest between the sell-side firm and the investor. For example, a firm may wish to invest its own capital in purchasing Sony shares. If, at the same time, that firm has a client that wishes to sell a large quantity of Sony shares, which hits the market before the buy orders, it could have the affect of moving the price in the firm’s favour.

MiFID best execution requirements Article 21 of the MiFID regulations states that financial services firms carrying out transactions on their clients’ behalf:

must take all reasonable steps to obtain the best possible result, taking into account price, costs, speed, likelihood of execution and settlement, size, nature or any other consideration relevant to the execution of the order.

Article 21 goes on to say that firms need to:

1. Establish an execution policy, which must contain information on the venues firms used to execute client orders. Those venues must allow it to consistently obtain the best possible result for execution for their clients;

2. Disclose the policy to clients and obtaining their consent to that policy;

3. Monitor the effectiveness of arrangements in order to identify and correct any deficiencies and review the appropriateness of the venues in its execution policy at least yearly; and

4. Upon client request, be ready to demonstrate that the client’s order has been executed in line with its execution policy.

8.5 THE UK PERSPECTIVE – THE ROLE OF THE FINANCIAL SERVICES AUTHORITY

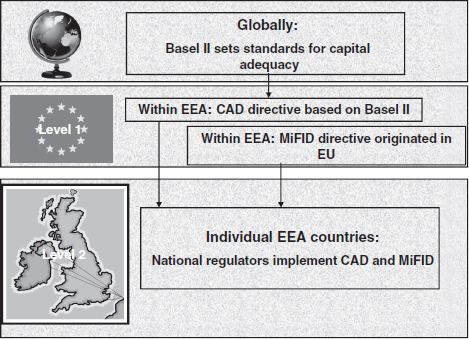

Figure 8.1 shows the linkage between the work of Basel II, the European Union and the national regulator: legislation enacted by the EU is known as Level 1 legislation. Level 1 legislation is often at a high level; the detailed instructions that have to be complied with are usually found in the individual legislation of the member states. This is known as Level 2 legislation.

Figure 8.1 Layers of international regulation

The UK regulator is the Financial Services Authority which was created by the Financial Services and Markets Act (FSMA) of 2000. The FSA undertakes both prudential regulation, which is concerned with ensuring that investment companies are financially sound, and business conduct regulation, which is concerned with the way business is transacted, in particular with the way that products are marketed and sold and investors are treated fairly. Broadly speaking prudential regulation comes under the auspices of the CAD, and business conduct regulation comes under the auspices of MiFID.

The FSA describes its approach to its work as “principles-based regulation”, which it defines as:

Placing greater reliance on principles and outcome-focused, high-level rules as a means to drive at the regulatory aims we want to achieve, and less reliance on prescriptive rules.

The 11 principles that it has established are:

1. A firm must conduct its business with integrity.

2. A firm must conduct its business with due skill, care and diligence.

3. A firm must take reasonable care to organise and control its affairs responsibly and effectively, with adequate risk management systems.

4. A firm must maintain adequate financial resources.

5. A firm must observe proper standards of market conduct.

6. A firm must pay due regard to the interests of its customers and treat them fairly.

7. A firm must pay due regard to the information needs of its clients, and communicate information to them in a way which is clear, fair and not misleading.

8. A firm must manage conflicts of interest fairly, both between itself and its customers and between a customer and another client.

9. A firm must take reasonable care to ensure the suitability of its advice and discretionary decisions for any customer who is entitled to rely upon its judgement.

10. A firm must arrange adequate protection for clients’ assets when it is responsible for them.

11. A firm must deal with its regulators in an open co-operative way, and must disclose to the FSA appropriately anything relating to the firm of which the FSA would reasonably expect notice.

Nevertheless, despite the fact that the FSA has adopted principles-based regulation, there are a large number of individual rules. These rules are published in the FSA Handbook, which is available online at http://www.fsa.gov.uk/Pages/handbook/.

8.6 SPECIFIC OFFENCES IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

IT practitioners working in the United Kingdom need to be aware of three specific offences of which investment firms and also employees of investment firms may be accused. The three offences are:

- Insider dealing

- Market abuse

- Money laundering.

Similar legislation exists in most countries; the UK legislation is quoted as an example of the type of legislation that exists globally.

8.6.1 Insider dealing

Insider dealing is a criminal offence in the United Kingdom under the Criminal Justice Act (CJA) of 1993. It is punishable by a fine or a jail term.

The offence of insider dealing is committed when an insider acquires or disposes of price-affected securities while in possession of unpublished price-sensitive information. The insider is also guilty of insider dealing if he encourages another person to deal in price-affected securities, or if he discloses the information to another person (other than in the proper performance of his employment). The acquisition or disposal must occur on a regulated market or through a professional intermediary.

To be found guilty of insider dealing, an insider in possession of inside information must commit the offence. The CJA provides the detail as to who is deemed to be an insider, what is deemed to be inside information and the situations that give rise to the offence. Inside information relates to particular securities or a particular issuer of securities (and not to securities or securities issuers generally) and:

- is specific or precise

- has not been made public

- if it were made public, it would be likely to have a significant effect on the price of the securities.

How price-sensitive information is made public

Listed companies have to announce price-sensitive information using a regulatory news service that disseminates it simultaneously to subscribers including the press and investment firms of all types. Regulatory news services are provided by a number of commercial organisations including stock exchanges and information providers such as Reuters and Thomsons. Listed companies have to announce price-sensitive information to these services as a condition of their listing. The type of information that they need to announce includes, inter alia:

- Final year end results and interim results

- Proposed dividends and other corporate actions

- Substantial changes of ownership

- Appointment and resignations of directors.

Any information of this type that has not yet been published on an RNS is, by definition, “unpublished, price-sensitive information”.

IT implications of insider dealing

The standard way of preventing leakages of this type of information is by the implementation of Chinese walls, which is examined in section 25.3.1. However, it is worth noting that technical support staff often have access to many sources of information including production feeds when diagnosing production issues. The impact of this information entering the public domain should be considered, and risk assessed especially when work is being carried out offsite or offshore, where secure access is not assured.

8.6.2 Market abuse

Market abuse is an offence introduced by FSMA 2000; judged on what a “regular user” would view as a failure to observe the required standards. The offence includes:

- Abuse of information

- Misleading the market

- Distortion of the market

- Manipulating the market

- Disclosing inside information

- Failure to observe the required standards.

The FSA is empowered to impose financial penalties on the firms and also the individuals that it regulates if they are found guilty of market abuse.

8.6.3 Money laundering

Money laundering is an offence under a number of instruments, including the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (POCA), the Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 (SOCPA) and the Money Laundering Regulations 2003.

Money laundering is the process of turning dirty money (money derived from criminal activities) into clean money (money that appears to be legitimate). Dirty money is difficult to invest or spend and carries the risk of being used as evidence of the initial crime. Clean money can be invested and spent without risk of incrimination. Money laundering is disguising the proceeds of illegal activities as legitimate money that can be freely spent. Increasingly antimoney laundering provisions are being seen as the frontline against drug dealing, organised crime and the “war against terrorism”. Much police activity is directed towards making the disposal of criminal assets more difficult and monitoring the movement of money.

There are three stages to a successful money laundering operation:

- Placement: This stage typically involves placing the criminally derived cash into a bank or building society account.

- Layering: Layering involves moving the money around in order to make it difficult for the authorities to link the placed funds with the ultimate beneficiary of the money. This might involve buying and selling foreign currencies, shares or bonds.

- Integration: At this final stage, the layering has been successful and the ultimate beneficiary appears to be holding legitimate funds (clean money rather than dirty money). Broadly, the anti-money laundering provisions are aimed at identifying customers and reporting suspicions at the placement and layering stages, and keeping adequate records which should prevent the integration stage being reached.

The Money Laundering Regulations 2003 and the FSA rules require firms to adopt identification procedures for new clients (to “know your client”) and keep records in relation to this proof of identity. The obligation to prove identity is triggered as soon as reasonably practicable after contact is made and the parties resolve to form a business relationship. Failure to prove the identity of the client could lead to an unlimited fine and a jail term of up to two years under the Money Laundering Regulations 2003.

The types of acceptable documentary evidence to prove the identity of a new client include the following:

For an individual

- An official document with a photograph (passport, international driving licence) will prove the name.

- A utilities bill (gas, water or electricity) with name and address will prove the address supplied is valid.

For a corporate client (a company)

- Proof of identity and existence would be drawn from the constitutional documents (Articles and Memorandum of Association) and sets of accounts.

- For smaller companies proving the identity of the key individual stakeholders (directors and shareholders) would also be required.

For a trust

The identity of the settlor (the person putting assets into trust), the trustees and the controller of the trust (the person who is able to instruct the trustees) would all be verified, along with a copy of the trust deed.

8.7 REGULATION AND ITS IMPACT ON THE IT FUNCTION

The impact of the regulatory environment upon an investment firm’s IT functions may be summarised as follows.

8.7.1 Impact on the application configuration

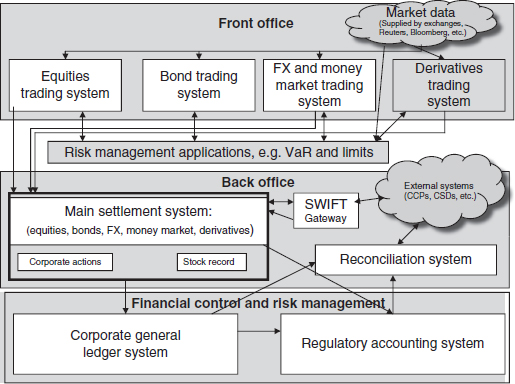

Look again at Figure 7.3, which is repeated here as Figure 8.2 for clarity.

Figure 8.2 Simplified investment bank configuration

First, the reason that the regulatory accounting system is present in the configuration is that regulators require firms to produce a statutory capital adequacy report each month – if this were not required, then there would be no need for the application at all.

Second, in this chapter we have mentioned that there are rules concerning, inter alia:

- Best execution, timely execution and customer order priority: Therefore the design of the front-office systems (the applications that are primarily concerned with the management of order flow) has to take these rules into account in its business logic if these regulations are to be complied with.

- Pre-trade publication of bid and offer prices: If the firm concerned was a systematic internaliser, then it would need to build in the ability to broadcast these prices to its customers in the relevant front-office systems.

- Post-trade publication of trade details within three minutes of execution: Again, business logic needs to be built into the front-office systems concerned in order to comply with this requirement.

- Client assets need to be reconciled: This is one of the reasons for the existence of the reconciliation application. Another reason for the existence of this application is that it used to detect problems that can lead to operational risk – specifically those risks caused by internal fraud and errors in execution, delivery, and process management.

8.7.2 Impact on the way that the department is managed

Poor management of the IT function would be a major contributor to an unacceptable level of operational risk. Let us remind ourselves of the seven operational risk events as defined by Basel II, and examine how poor IT practice can increase operational risk, while good practice can mitigate it:

1. Internal fraud: Misappropriation of assets, tax evasion, intentional mismarking of positions, bribery

These activities can be facilitated by practices that allow, inter alia, unauthorised access to applications and underlying data. They may be mitigated by the use of application password control and the deployment of systems that support the concept of segregation of duties.

2. External fraud: Theft of information, hacking damage, third-party theft and forgery

As for (1) above, but in addition these problems can be mitigated by the deployment of antivirus software, anti-spyware software, firewalls, etc.

3. Employment practices and workplace safety: Discrimination, workers, compensation, employee health and safety

There are no specific IT-related issues to this event, it is a company-wide issue.

4. Clients, products and business practice: Market manipulation, antitrust, improper trade, product defects, fiduciary breaches, account churning

“Product defects” in this context includes defects in the software and hardware that is used to process the firm’s data. Good IT practice involves the use of standardised, reliable methodologies to discover and document business requirements, select software vendors and packages, build, test and deploy software and manage projects. It also involves the use of configuration management and change control procedures to ensure that the right software versions are deployed. These topics are examined more deeply in Chapters 25 to 27.

5. Damage to physical assets: Natural disasters, terrorism, vandalism and:

6. Business disruption and systems failures: Utility disruptions, software failures, hardware failures

These risks may be mitigated by proper business recovery plans which are examined in Chapter 25. Software failures may also arise as a result of product defects (Basel II Event no. 4).

7. Execution, delivery and process management: Data entry errors, accounting errors, failed mandatory reporting, negligent loss of client assets

These events, in turn, may be caused by product defects.

8.7.3 Other regulations that affect the IT department

In addition to the regulations that are imposed on the firm by its financial regulator, there will be many other regulations imposed on them by other legislation that is common to companies of all kinds, such as legal restrictions concerning data retention and data protection, as well as general accounting and tax requirements. Some of these will be examined in more detail in Chapter 25.