Project planning for

risk, prioritization

and benefits

3.1 Introduction

Risk in computer-based projects are surprisingly undermanaged.

Willcocks and Griffiths1

We've minimized risk because we are sharing the risk (between the client and the vendor) . . .

Assistant Executive Officer, California Franchise Tax Board

What we tend to find with IT projects is that they may not produce a positive NPV. And what I'm trying to get people to do more and more is recognize that some projects are enablers and not every project you do is going to pay back. So just recognize that some of it is invested in the infrastructure of the business.

Financial Controller, Major Retail Company

Focus has been less on only cost and more and more emphasis on ‘what should we be doing to move our business ahead’ . . . managers of the larger projects begin to speak about the IT investment now more in terms of return versus simple cost minimization.

Information Technology Manager,

Hewlett Packard Test and Measurement Organization

In this chapter, we will identify approaches for justifying and planning IT projects. Remenyi has capably and effectively covered risk assessment in his book Stop IT Project Failures Through Risk Assessment (in this same Butterworth-Heinemann series), but a brief discussion of risk from a complementary perspective is relevant at this juncture. Despite their importance to all phases of an IT/e-business project, and especially in the initial assessment, risk assessment and management are often overlooked throughout those phases because:

(1) the client/users care less about development productivity than about the ultimate product's fit-for-purpose;

(2) additional time is required for measurement in a schedule that is already tight;

(3) there is lack of knowledge of effective measurement approaches;

(4) of adherence to a traditional lifecycle design methodology which does not specify adequate measurement;

(5) there is lack of organizational learning from previous projects; and/or

(6) the IT organization already has approval for the project; now the focus is on delivery of an end product.

Risk is to be understood as exposure to the possibility of a loss or an undesirable project outcome as a consequence of uncertainty. The failure to consider risk has been the downfall of many IT investments. We will now review specific examples and consider possible risk-mitigating techniques.

3.2 Why IT-based projects fail

Research and experience alike continually cite a failure to measure risk. For instance, the OTR Group found that only 30% of companies surveyed in 1992 applied any risk analysis in the IT-investment and project-management processes. Depressingly, in two later surveys, Willcocks found that ‘little formal risk analysis was identified amongst respondent companies, except that in financial calculation, e.g. discount rates’1. In addition, in 1998 Willcocks and Lester found that in some organizations up to 40% of the IT projects realized no net benefits, however measured.

On a daily basis, the trade press reflects examples of failed projects. The following examples of outright project failure provide a basis for the consideration of risk and its contribution to on-going project assessment.

– The London Stock Exchange's TAURUS (Transfer and Automated Registration of Uncertified Stock) project was conceived in the early 1980s as the next automation step toward a paperless dealing and contractual system for shares. The main impetus for TAURUS came in 1987 with a crisis in settlements stemming from back office, mainly paper-based, support systems failing to keep track of the massive number of share dealings and related transactions. Many of the international banks were keen to automate as much as possible and as quickly as possible. Other parties, such as registrars who would be put out of business if share certificates were abandoned, fought against any further expansion of technology. Consequently, the Stock Exchange had to balance its international reputation while maintaining the support and confidence of all City interests.

The Siscott Committee was appointed by the Bank of England to provide some sort of compromise solution. Unfortunately, with each compromise, expectations, systems design and complexity of the desired solution increased exponentially. Additionally, the Department of Trade and Industry began to impose restrictions to protect investors. In the confusion, the main project focus was lost and the decision between a massively centralized computer system or an integrated network of databases remained undecided.

Eventually, a project team was appointed and given the goahead to purchase for the core system a £1 million software package from Vista Concepts in New Jersey. Work commenced on customization of the system, despite the lack of a central design for the system and the absence of a planned operating architecture. The project grew out of control very quickly and ultimately was declared an outright failure.

The outcome of the TAURUS project is perhaps the most familiar large-scale IT project failure in the UK. A multitude of sins comprises the list of errors on the project:

(1) up front, the project lacked clear objectives;

(2) the size and complexity of the project were unaccounted for in terms of appropriate controls;

(3) communication channels across many aspects of the project were poor at best;

(4) project procedures were not followed;

(5) quality control was limited by the lack of accountability on the project;

(6) sourcing decisions were made with no rhyme or reason;

(7) vested parties were not in agreement on the ‘solution’;

(8) no central design for the system existed;

(9) no operating architecture had been planned; and

(10) the appointed committees failed to reach any compromises and/or engender the support of appropriate parties.

– The Governor of California pulled the plug on the US$100 million plus State Automated Child System (SACSS) in response to repeated project slippages and the rampant dissatisfaction voiced by counties already live on the system (note that the SACSS implementation plan called for a phased roll out to the counties originally spread over 12 to 18 months). This failure fell in line behind several other large IT project failures for the State of California including a Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) US$50 million debacle. A number of issues can be cited regarding the failure of SACSS:

(1) the system was intended to be transferred from one implemented in a state with a much smaller caseload. Consequently, the original application was not built for a caseload with the size of California's; the resulting ‘enhancements’ resulted in a nearly entirely redesigned application;

(2) the system was intended to run as 58 individual county systems all connected through a central hub database which permitted communications between counties; the resulting inability to engender agreement across counties for functionality severely crippled the developer's ability to deliver;

(3) the application was not sized correctly for the hardware to be used;

(4) the timescale of the project created a situation where the application to be delivered was relatively out of date when rolled out to the initial counties;

(5) project complexity confused many issues;

(6) project management suffered due to multiple vendors and continual staff changes at the State level; and

(7) the system was mandated by the federal government without acknowledgment of the complexity required to satisfy the generic requirements.

TAURUS and SACSS were big projects, often using new technology while lacking big project disciplines. Large e-business projects run similar risks – no new rules here. Moreover, by definition, e-business projects also involve considerable re-engineering and organizational change risks. How should risk be addressed? What repeatable and consistent approaches can be applied to the assessment, management and mitigation of risk in any sort of IT undertaking? In answer, we will review several perspectives on the many dimensions of risk, then suggest a set of prevalent risk factors for consideration and on-going evaluation.

The portfolio dimensions of risk

McFarlan's portfolio approach to project management2 suggests that projects fail due to lack of attention to three dimensions:

(1) individual project risk;

(2) aggregate risk of portfolio of projects; and

(3) the recognition that different types of projects require different types of management.

For example, a simple support application with relatively straightforward specifications and a goal of increasing efficiency would require only simple task management, whereas a highrisk strategic application would require more management directed at risk mitigation. Moreover, the risk inherent in projects is influenced by project size, experience with the technology and project structure. All of the caselets provided demonstrate this failure to assess project risk. Additionally, from McFarlan's proposals, it seems obvious that risk assessment on one project is complicated by an organization's need to manage many such projects at once.

The domains of risk relative to IT investments

Lyytinen and Hirschheim3, supplemented by Ward and Griffiths4, describe the domains of potential failure as:

– technical – the domain of IT staff, who are responsible for the technical quality of the system and its use of technology (this is usually the easiest and cheapest problem to overcome);

– data – describes the data design, processing integrity and data-management practices under the control of IT combined with the user procedures and data quality control handled by the user (this is clearly a shared responsibility);

– user – the primary responsibility for using the system must lie with user management;

– organizational – describes the possibility that, while a system may satisfy a specific functional need, it fails to suit the overall organization in its operations and interrelationships; and

– business environment – the possibility that a system may become inappropriate due to change in market requirements and related changes in business strategy.

The domains of failure, then, can span the breadth of the organization and depend on external influences as well.

The sources of risk

Willcocks and Griffiths5 present a complementary perspective on why an IT project might fail. Their research reflects five broad categories contributing to such failures. We'll explain these five categories in light of the failed project examples provided earlier.

(1) Lack of strategic framework. The California SACSS project illustrates a lack of strategic framework. It failed to convince the 58 counties’ users of the benefits of SACSS. The resulting in-fighting about system functionality prevented a cohesive system. In addition, perhaps because the original concept for the SACSS was a federally mandated requirement, a strategic focus owned by the state never developed.

(2) Lack of organizational adaptation to complement technological change. Again, the SACSS project was intended for implementation in 58 counties, all of which previously conducted business in 58 different ways. Efforts to educate users in the context of their existing systems failed to convince users to adopt the new application.

(3) IT supplier problems and general immaturity of the supply side. The TAURUS project was based on a piece of vendor-supplied packaged software that required so much customization that £14 million in additional funds was required to rewrite the software; even so, the effort was never completed.

(4) Poor management of change. The projects mentioned paid little attention to the management of change. Project management was questioned in its effectiveness on all projects, and users were either not effectively involved in development processes or were not well informed about upcoming changes. Project management focused on the delivery of the physical and/or tangible product with little attention to (indeed no assigned responsibility for) the more subtle and less tangible aspects of organizational change required by the overall business need/metric for which the systems were being built.

(5) Too much faith in the technical fix. The TAURUS initiative illustrates the keen desire to implement customized automation technology regardless of the lack of an appropriate central design. It was thought that automation was the ‘beall’ solution without regard to the ramifications of such an approach.

While the ‘technological’ focus of an IT project is obvious, it is perhaps less obvious and often forgotten, that an IT project should not be an end in itself. Instead it should be a means to support a more comprehensive business project and related business metric. Although technology plays a part in the reasons provided for project failure thus far, the more significant factors (and those less easy to repair) appear to be organizationally and human-related. Willcocks and Griffiths reference a survey of abandoned projects which were halted due to organizational factors (e.g. a loss of management commitment) and/or political and interpersonal conflicts, rather than technical issues. Thus, the number of project risk factors to be evaluated on a continual basis throughout the life of a project expand from merely technological factors to include organizational and human dimensions.

Ultimately, Willcocks and Griffiths summarize succinctly the required attention to risk: ‘underlying all the issues so far identified is the degree to which risk factors and level in largescale IT projects are explicitly recognized, then managed’.

Much of what has been discussed here relates to analysis that precedes a project undertaking. In looking at project management and development issues, these analyses must be thought of as an on-going review process. Risk cannot be assessed only once with the expectation that such assessment will be satisfactorily for the life of a project. With a ‘project lifecycle’ concept in mind, consider the following successful examples of risk mitigation.

3.3 Successful risk mitigation: some examples

The following caselets examine organizations that consciously adopted some tailored form of risk mitigation. The common significant factor of success in each case was the simple fact that risk was recognized and planned for.

– BP Exploration's global IT organization, XIT, has been measuring financial information since its creation in 1989. In 1993, XIT outsourced all of its IT supply services. In the same year, XIT introduced the balanced business scorecard as a means to assist in the transformation of the remaining IT function from a traditional IT group to an internal consultancy focused on adding value to the business units. The balanced business scorecard went through a number of iterations before it reached its current form. In its metamorphosis, XIT recognized the need for risk assessment and management. Consequently, it has added a risk matrix to the performance management process. The matrix maps risk probability against risk manageability and is used to map identified risks according to these two dimensions. In doing so, BP XIT makes explicit risk elements and provides a vehicle to communicate to the organization the significance of those risks.

– As will be demonstrated by the case study at the end of Chapter 4, the CAPS/PASS projects for the California Franchise Tax Board created an environment of shared risk between vendor and client. AMS bore the burden of development costs while creating a new saleable product; FTB donated a great deal of staff time and knowledge to the development of a flexible solution within the constraints of defined benefit streams, perfected as the project proceeded. Project team members worked hard to identify risks before they became impediments. The balancing of benefit, cost and quality created a keen focus on project goals: both client and vendor concentrated on making investments which added measurable value to the organization.

3.4 Risk assessment: emerging success factors

From the discussion above and the examples of successful risk mitigation, we can identify a number of dimensions that contribute to the ability to assess and mitigate risk in the design, development, implementation and post-implementation phases of a system's lifecycle. These factors provide the setting for an examination of various project measurement methods in Chapter 4.

User involvement

The user's involvement in a project is inherent to a project's success. Such involvement is required to provide information about the business setting in which a new IT project is to be implemented. The user explains the business processes that are being automated perhaps and/or the innovative opportunity technology can provide to accomplish a task not yet surmountable. Regardless of their need to be involved, history shows that user involvement in projects is relatively negligible. Some traditional lifecycle development methodologies specify that the users are involved in the ‘functional specification process’ then effectively disappear until acceptance testing. How should users be involved in the design and development process in an effective and cooperative manner? More importantly, how can users provide measurements of progress and success in the design/development process?

Commitment from management, key staff and IT professionals

In order to see a project through to its end, a number of parties are required to participate. The levels of participation may vary, but the vested interest on behalf of management, key user staff and IT professionals is a necessity. These parties can contribute to the successful process of on-going measurement during design, development and implementation.

Flexibility

There is much debate about flexibility in the continual updating of functional specifications, program design and program code. Again, more traditional lifecycle models specify that functional specifications should be shut down at a certain point based on a project description that is probably outdated by the time the project actually begins. Confusion in the design and development process reigns because of the constant specification discussions. Perhaps, however, some level of flexibility built into the process would ease the tension and make the design and development processes more effective.

Strategic alignment

Strategic alignment is required for an IT department as a whole and as part of the investment process. ‘One-time’ alignment is not enough. Again, because of the rapidly changing horizon for both technology and business, strategic alignment could disappear before an approved project has been completed. Consequently, on-going strategic alignment assessment must be performed. Increasingly, especially with moves to e-business, an IT project should really be supporting a more comprehensive business project, and that business project should provide business metrics with which the IT project can align. Thus, the business project as a whole must continue to answer the strategic needs of the organization in order for the subsumed IT projects to do the same.

Time constraints

There is an increasing body of evidence suggesting that largescale, long-time IT projects are particularly susceptible to failure. The SACSS project in California, examined in the beginning of the chapter, is a case in point. On the other hand, the time dimension can provide an effective measurement stick to monitor design and development. Organizations are more often imposing time caps on IT projects for the sake of driving requirements through quickly without losing out on available opportunities.

Project size

As demonstrated by the SACSS project, the overwhelming size of a project, as a single factor, can significantly impair the ability to deliver. In those instances the recommended response is to break the project down into smaller pieces in order to develop a reasonable delivery schedule.

Scope control

Many projects suffer from ’scope creep’, that is the inimitable addition of functionality at later stages in the project outside the formal planning process and outside of allegedly ‘nailed down’ specifications. In Chapter 4, it will become obvious that traditional methodologies specifying a limited time for specification development might not serve the best purpose. For now, scope control should be considered a hazard of ineffective working relationships between users and IT staff.

Contingency planning

In the quick-moving world of technology and IT project delivery, project plans and budgets are usually stripped to the bone. Research has demonstrated time and again, however, that contingency planning and padded estimates could do wonders to establish appropriate expectations on behalf of both users and IT staff, as well as to create a more effective working environment.

Feedback from the measurement process

Finally, assuming that all of these project/risk variables should be taken into account when planning any kind of management/measurement system, it is important to remember that the measurement process should provide feedback into the organizational learning loop, which can continually improve the organization's ability to perform and analyse risk. In other words, risk assessment and measurement must feed into a system of risk management in order for risks to actually be preempted and dealt with.

3.5 Project planning issues

Now that we have established a case for on-going risk analysis, we will examine the other dimensions of project planning. The following caselets provide detail about managers in large, complex organizations, and their approaches to feasibility assessment, planning and prioritization, and benefits management.

– The Chief Information Officer (CIO) of Genstar Container Corp (GE subsidiary) always takes the ‘business approach’ in the assessment of IT investment. The IT organization has undergone a dramatic transformation since the beginning of 1997 and the assignment of Jonathan Fornaci as CIO. Since 1997, Genstar has overhauled all of its technology base and moved to an Internet/Java-based set of applications to support the customer. The first step in getting to the ‘new’ vision was to subsume the technology under the business case. In the eyes of Genstar, that business case must have the singular goal of attaining closeness to the customer via the exploitation of IT. Interestingly enough, the CIO explains that the business case analysis is built solely on ‘hard costs’; intangibles are not included.

– A large financial services organization based in the UK is moving toward an era in which all IT investments need to be about commercial ventures rather than about technology. This new perspective has contributed to making a number of key IT investment decisions, for example the decision to outsource voice and data network support and development. The IT organization determined that, while the company could easily build its own voice and data networks, it would incur an opportunity cost by doing so.

– As the multinational pharmaceuticals firm Glaxo Wellcome entered 1998, it was undergoing significant cost rationalization in the face of patents which expired in mid-1997 and declining market share, both of which resulted in a less cashrich environment. The centralized IT department was experiencing the results of this new cost-consciousness, as the International IT Manager, explained:

In the good old days of Glaxo before the merger (with Wellcome) when we were growing at 20% odd per annum because of one particular product no one cared too much about putting a decent cost benefit analysis together, we didn't care too much about the internal rate of return or payback. Certainly, measuring the benefits was something that was never spoken about. A lot has changed and now any case for expenditure will be carefully scrutinized. We will look at how quickly it's paying back to the business. We will be looking for a very solid business case. And we will be looking for evidence that someone somewhere is trying to put into place a process at the end to measure benefits.

Budgeting and project prioritization were also affected into 2000: ‘The organization is finding difficulty with determining an effective overall budget given the piecemeal approach of project development. Hard-nosed prioritization is becoming a necessity.’

In these cases, it can be seen that, until comparatively recently, most assessment and planning has been predominantly financially based. Research evidence up to 2001 continues to indicate that although organizations understand the need for comprehensive evaluation conceptually, they have been a long time in recognizing that a financially based investment case does not provide the complete story about IT investment. Amongst other things, managers struggle with the types and identification of less tangible benefits.

Our most recent research suggests that 70% of organizations practise some sort of feasibility assessment, yet a significant portion of those organizations rank ‘difficulty in identifying benefits, particularly intangible benefits’ along with ‘difficulty in assigning costs to benefits’ as the most notable obstacles in feasibility assessment. Moreover, organizations identified ’strategic match with the business’ and ’satisfaction of customer needs’ as the most critical criteria affecting the investment decision, followed closely by ‘return on investment’ and ‘traditional cost benefit analysis’. It would appear that these criteria reflect a subtle shift in evaluation practices toward less tangible benefits, with supporting financial analysis.

Whereas organizations once hoped to cut costs by automating, now organizations have discovered completely new ways of doing business that expand both the need for IT investment and the profitability of the business. The successive adoption of the new technologies, including Internet-based technologies, has complicated the process of analysing new IT investments because:

(1) resulting paybacks/benefits cannot be measured solely in terms of money spent or saved;

(2) resulting benefits filter throughout the organization, sometimes in surprising and unpredictable ways; and

(3) the overall role of IT has changed from being supportive to also being of strategic importance; moreover, the benefits derived from IT investments have evolved from time and cost savings to the provision of additional competitive advantage, cooperative advantage, diversification and new marketing opportunities.

Regardless of these complications, measurement processes that begin with a feasibility assessment can assist more effectively in the task of identifying costs, investments, intangible benefits and consequently, measuring those same effects throughout the life of the project. Overall planning and prioritization of IT projects can provide a bird's-eye view of the whole picture and how various projects relate to one another and to other initiatives and operations within the organization.

3.6 Planning and prioritization approaches

The practices exhibited in the following Hewlett Packard case are typical of the better practitioners of planning and prioritization. Even so, it is fairly clear that there is plenty of opportunity for improvement.

– In 1998 the IT department of the Test and Measurement Organization (TMO) within Hewlett Packard had relatively rudimentary project assessment processes in place. According to Steve Hussey, TMO Information Technology Manager:

I would characterize our assessment here as being pretty much on the front end of the learning curve. Most are not very sophisticated. The reason I say that is because on large investments, assessments tend to be more robust, and there's always a financial component. Increasingly, there is a business strategy, business impact component .. . and on the end of the spectrum, for smaller projects, there is often little return analysis in the traditional sense at all, because those projects may move very quickly, and there's not a lot of analytical framework around them. However, almost all projects go through a fairly disciplined project lifecycle process.

He does note that the decision process differs, depending on the part of the investment portfolio under consideration. For instance:

At the highest level, overall infrastructure strategies are supported by the senior level executives in the business; the infrastructure investment is usually not based on a return to the business in the more traditional sense . . . There's a different set of investments that I would term project or solution based, and those decisions are usually based completely on business needs . . . Those are all business based, they are not based on an IT strategy by themselves, they are based on what we need to do in the business. In these cases, the IT investment levels are really part of the overall business program. Those IT investments tend to be measured much more on a return basis.

The planning process derives significance from the fact that it is the way into identifying application needs and allocation of resources. Some combination of top-down and bottom-up planning is required in order to:

(1) identify and understand organizational strategy;

(2) understand IT capability and applicability; and

(3) develop a plan, albeit a flexible one, for future IT undertakings.

Let us turn to investigating possible best practice in this area.

Application portfolio analysis

As far back as 1981, McFarlan recommended that organizations should analyse their technology/systems investments by assessing risks across the portfolio of applications in the organization6. As addressed earlier in the risk assessment discussion, he suggested three ’serious deficiencies’ in IT management practice:

(1) the failure to assess individual project risk;

(2) the failure to assess aggregate risk across the application portfolio; and

(3) the failure to recognize that different types of projects require different types of management attention.

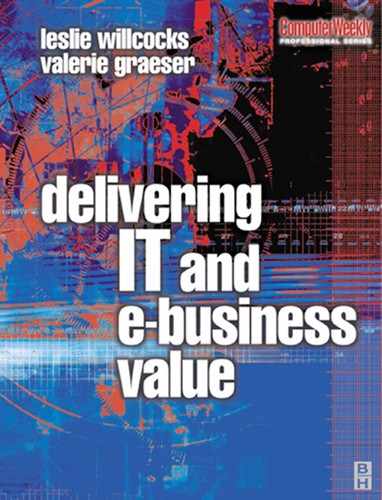

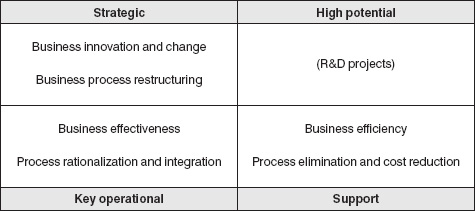

Since McFarlan's recommendations, a number of ways of categorizing IT application have arisen, including those suggested by Willcocks7, Farbey, Land and Targett8, and Ward and Griffiths9 (see Figure 3.1 for a summary of these classification schemes). As will be examined later in the chapter, each application type gives rise to variations in benefits. This suggests that different types of applications require different evaluation and management approaches.

The use of a classification process to identify the application portfolio can assist the organization in the planning and prioritization process, and, as McFarlan suggests, it can help assess technology risks in a more comprehensive manner.

Figure 3.1 Classifications of IT applications

Planning and prioritization: a business-led approach

Planning and prioritization in its simplest iteration can be thought of as aligning, at a very early stage, business direction and need with IT investment. A complementary way of looking at the issue is the business-led approach suggested by Feeny in Willcocks, Sauer and associates in Moving To E-business (2001)10. This examines IT investments in light of the concept that IT expenditure alone does not lead to business benefits. Feeny points out that only the adoption of new business ideas associated with IT investment can lead to significant business benefits: ‘If there is no new business idea associated with IT investment, the most that can be expected is that some existing business idea will operate a little more efficiently, as old existing technology is replaced by new.’ The analysis he pursues to arrive at this key point encapsulates and reformulates a combination of the planning and prioritization approaches already discussed.

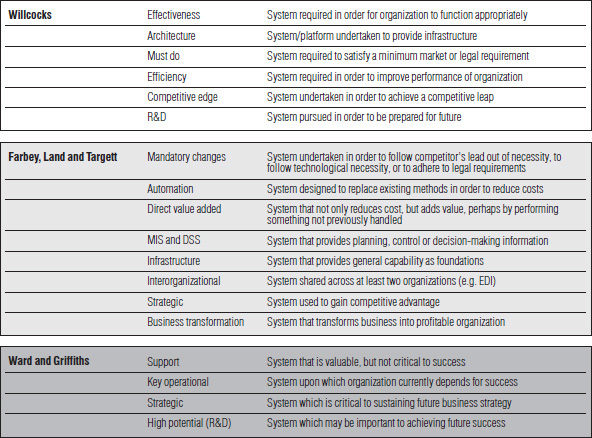

Developing David Feeny's work, we suggest that five IT domains exist, and by referring to each domain executives can assess their organizational goals for IT. Figure 3.2 represents the five domains.

(1) IT hype. This domain goes beyond the actuality toward a focus on potential capabilities and outcomes. The information highway, predicted to transform the existence of every individual, is a good example of where the IT rhetoric goes beyond what actually can be provided reliably.

(2) IT capability. Within IT hype lies the every-increasing domain of IT capability, comprising products and services available today for organizations to exploit. Within this domain, the counterpart to the information highway is the Internet: it does exist and is used by organizations. Clearly, other technology strands are more mature than the Internet; the sum total of this domain represents a vast tool-kit of technology.

(3) Useful IT. No organization uses everything available in the IT capability tool-kit; consequently, this domain consists of all the investments that provide at least a minimum acceptable rate of return to the organization.

(4) Strategic IT. This domain comprises the subset of potential investments which can make a substantial rather than marginal contribution to organizational achievement.

(5) IT for sustainable competitive advantage. Scale (gaining a dominant market position in a broad or a niche market), brand and business alliances are significant factors for highprofile Internet exponents such as Dell, Amazon and Cisco Systems, Yahoo and AOL. However, sustainable advantage also comes from generic lead time, and more importantly building asymmetry and pre-emption barriers.

These IT domains allow the further examination of organizational goals for IT. Feeny defines organizational exploitation of IT to be successful navigation through the domains, such that organizational resources become consistently focused on ’strategic IT’ rather than merely on ‘useful IT’. Consequently, the next issue to be addressed is the manner in which an organization navigates through the domains. Feeny outlines the following three approaches.

(1) In an IT-led approach, senior management look to the IT function to assess professionally the domains and to propose an agenda for IT investment. Most organizations have operated in this manner at some point in the lifetime of technology. The difficulty with this approach lies in the inherent lack of application purpose for IT. In other words, technology's application is defined at the point of use, not at the point of manufacture. Consequently, the relevance of technology is a function of the user's imagination, not that of the product designer. The desire on behalf of the IT professionals to learn and understand new technology, and to attempt to apply it in a useful manner for the organization, results in ‘IT capability’ or at best ‘useful IT’ rather than ’strategic IT’.

(2) In a user-led approach, the natural response to the lack of application purpose is for the users to develop and argue the investment cases for technology usage. Unfortunately, this approach also commonly results in merely ‘useful IT’ for a number of reasons. Firstly, only a number of users take up the challenge, and who that do tend to be IT enthusiasts (and so subject to the same issues as the IT professionals in making recommendations). Secondly, the users are operating within a bounded domain of responsibility. Consequently, their proposals may represent potential improvements to non-critical portions of the business.

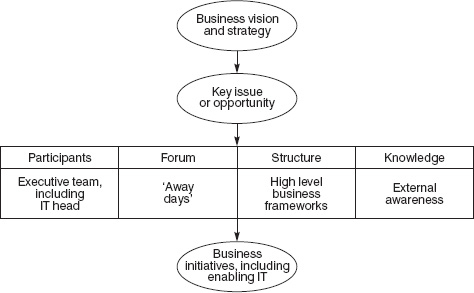

(3) The business-led approach is represented by Figure 3.311. The navigation process is reversed from outside in to inside out. The business-led approach works on the assumption that anything is possible, envisions the ideal business initiative, then checks to see if the necessary IT is available. The second aspect of this business-led approach is that the IT investment evaluation flows naturally from the navigation process. Most organizations still operate investment appraisal processes that demand cost benefit analyses of the proposed IT expenditure. The business-led approach requires that the adoption of new business ideas (rather than the IT expenditure) leads to business benefits and consequently to ’strategic IT’, as a step towards ‘IT for sustainable competitive advantage’.

Feeny's approach provides a categorization of IT in the form of domains, a target domain for effective IT expenditure and a navigational tool through the domains. The usefulness of the approach derives from its prescriptive direction.

Figure 3.3 The business-led approach (source: Feeny, 2000)

3.7 Feasibility assessment

Whether or not organizations pursue risk assessment and project prioritization, most are pursuing some forms of feasibility assessment. Feasibility assessment is best defined as ‘evaluating the financial and non-financial acceptability of a project against defined organizational requirements, and assessing the priorities between proposed projects. Acceptability may be in terms of cost, benefit, value, socio-technical considerations ’12

Of course, feasibility assessment is only one step in the process of directing attention to IT spend as investment. The following will examine a number of significant feasibility assessment approaches found in the organizations. The approaches will be described together with an investigation of their benefits and limitations.

Return on investment

Return on investment was the feasibility evaluation tool most often mentioned, and is also known as the ‘accounting rate of return’. It depends on the ability to evaluate the money to be spent on the IT investment, and the quantification, in monetary terms, of a return associated with that investment. In other words, simple return on investment is the ratio of average annual net income of a project divided by the internal investment in the project. A refined version of return on investment is the evaluation of current value of estimated future cash flows on the assumption that future benefits are subject to some discount factor. The internal investment should include both implementation costs and operating costs. To apply return on investment to the feasibility investment, one would compare a rate of return against an established ‘hurdle’ rate to decide whether to proceed with a project. Although the technique permits decision-makers to compare estimated returns on alternative investments, it suffers from a number of weaknesses:

(1) unfortunately, the financial figures resulting from this sort of analysis are just that: financial in nature and accommodating only hard costs;

(2) ‘good’ investment possibilities may be withheld because benefits are difficult to assess in attributable cash flow terms;

(3) consequently, a project analysed under this approach may not provide a favourable return on investment and fail to be approved, even though other intangible benefits, such as increased competitive advantage, may be apparent.

Cost benefit analysis

An example of cost benefit analysis is as follows.

– In the late 1990s, the IT investment decisions of the Royal & SunAlliance UK Life and Pensions involved the right people with the right experience. All potential investments were reviewed by the Life Board Finance Committee. Each potential investment required an IT sponsor who needed to make a case for IT expenditure based on cost benefit analysis accompanied by a business rationale. Standard criteria included payback in two years and a fit with the strategic plan. For infrastructure investments, the organization asked the question: ‘What will happen if we don't do it?’

A sound cost benefit analysis includes the use of discounted cash flow to account for the time value of money, the use of life cost analysis to identify and include the spectrum of relevant costs at each stage of the lifecycle, the use of net present value to aggregate benefits and costs over time, and the use of corporate opportunity cost of capital as the appropriate discount rate in discounted cash flow calculations. By way of explaining the process of cost benefit analysis, consider the following five steps.

(1) Define the scope of the project – all costs and benefits should be evaluated. In practical terms, this is not always possible and it is important that any assumptions and limitations are clearly defined and agreed up front.

(2) Evaluate costs and benefits – while direct costs are usually relatively straightforward to quantify, benefits and indirect costs are often problematic. Potential benefits can be identified by using a checklist and sometimes can be estimated only crudely.

(3) Define the life of the project – this definition is required because the further into the future the cost/benefit analysis reaches, the more uncertain predictions will become.

Furthermore, benefits will continue to accrue over the life of the project, so that the longer it continues, the more likely a favourable return on investment will appear. A risk in this definition is the failure to account for on-going, postimplementation costs such as those for maintenance.

(4) Discount the values – most cost benefit analyses attempt to take into account the time value of money by discounting anticipated income and expenditure. The corporate opportunity cost of capital has been widely considered to be an acceptable approach.

(5) Conduct sensitivity analysis – examine the consequences of possible over- and under-estimates in costs, benefits and discounting rates.

Cost benefit analysis is widely used. It is important to caution, however, that while benefits are considered in the assessment, the benefits identified tend to be traditional in nature and avoid some of the softer benefits associated with new technology.

Critical success factors

An example of the use of critical success factors is as follows.

– A major multinational retailer regularly uses critical success factors in its quarterly evaluation of IT performance. The Senior Manager of IT Services, explains:

We have what we call our critical success factors, performance measures of the organization. We monitor those on a quarterly meeting of our senior management team with the Managing Director. We discuss the results, formulate actions plans. What you've got is a planning process where we have a business plan for the year which includes our objectives, our strategies for improvement and our performance measures. We then regularly review those and adapt the plans. So you get the effect of achieving your objectives at what you set out at, and you get performance improvements year on year. And that's what we use as a process.

The use of critical success factors is a well-known ‘strategic’ approach to evaluating information systems. Executives express their opinions as to which factors are critical to the success of the business, then rank those factors according to significance. Following this exercise, the organization and the executives can use these critical success factors to evaluate the role that IT in general, or a specific application, can play in supporting the executive in the pursuit of critical issues. The method is significant in light of its focus on those issues deemed important by the respondents; in other words, those issues which will be revisited if trade-offs in IT decisions are required.

Return on management

Return on management, developed by Strassmann13, is a measure of performance based on the added value to an organization provided by management. Strassmann assumes that, in the modern organization, information costs are the costs of managing the enterprise. In this sense, information costs are equated with management. If return on management is calculated before and then after IT is applied to an organization, then the IT contribution to the business (so difficult to measure using more traditional measures) can be assessed. Return on management is calculated in several stages:

(1) total value added is established from the organization's financial results as the difference between net revenues and payments to external suppliers;

(2) contribution of capital is then separate from that of labour;

(3) operating costs are then deducted from labour value added to leave ‘management value added’; and

(4) finally, ROM is calculated as the management value added divided by the costs of management.

While return on management presents an interesting perspective on the softer costs associated with IT, one must question the validity of the underlying assumption that ‘information costs are management costs’. Moreover, the before and after approach may indicate that this method is better suited to the evaluation of existing systems than initial feasibility assessment.

Net present value

An example of the use of net present value is as follows.

– A large UK-based retailer we researched used net present value to evaluate IT investments. Although the organization used fundamentally financial measures of investments, including net present value, it was beginning to understand that hard financials were not the only effective measure of a sound IT investment. The Corporate Financial Director explained:

What we will do for each project is record the P&L [profit and loss] impact of the current year, the P&L impact of the next year, the cash flow impact of the current year, the level of capital expenditure, net present value, IRR [internal rate of return], payback ... it's actually a combination of them all . . . everything is (evaluated) on a 5-year basis and we use cost of capital of 13.25. That's the consistent (investment evaluation process) across all projects. What we tend to find with IT projects is that they may not produce a positive net present value. So that, on cost of capital, they may actually look as though they are losing us money. And what I'm trying to get people to do more and more is to recognize that some projects are enablers and not every project you do is going to pay back. So just recognize that some of it is invested in the infrastructure of the business.

Net present value can be considered to be an effective approach to investment appraisal in so far as it allows for benefits to accrue slowly and provides a clear structure which can help in overcoming the political and hyped claims sometimes attached to IT projects. On the other hand, a number of problems arise with the use of net present value. In the first place, its use does not encourage the consideration of project alternatives, instead it tends to encourage the concept that the alternative under consideration is the ‘right’ way. Additionally, net present value is complicated by the need to select an appropriate discount rate. Finance theory indicates that the cost of capital adjusted for risk is the appropriate discount factor, but an adjustment to accommodate risk is very subjective in nature.

Net present value can be adapted in the following three ways to circumvent the problem with intangible benefits:

(1) alternative estimates of intangible benefits (i.e. associating a tangible cost) can be entered into the net present value model to explore the project's sensitivity to the delivery of intangibles;

(2) expected values can be used in the net present value model – expected values are obtained by multiplying the probability of an intangible benefit by its estimated value; or

(3) net present value can be calculated only for cash flows of the tangible benefits and costs – if it is positive, accept the project; if it is negative, calculate the values required from the intangible benefits to bring it to zero, then assess the probability of achieving these values for intangibles.

Information economics

The Parker et al.14 information economics model for linking business performance to IT is primarily an investment feasibility model. In this model, demonstrated in Figure 3.4, ‘value’ is identified by the combination of an enhanced return on assessment analysis, a business domain assessment and a technology domain assessment. The components of these various assessments are touched upon as follows.

| value | = | enhanced return on investment |

| + | business domain assessment | |

| + | technology domain assessment |

Enhanced return on investment includes:

– value linking – assesses IT costs which create additional benefits to other departments through ripple or knock-on effects;

– value acceleration – assesses additional benefits in the form of reduced timescales for operations;

– value restructuring – used to measure the benefit of restructuring jobs, a department, or personnel usage as a result of IT introduction, and is particularly helpful when the relationship to performance is obscure or not established as in R&D departments and personnel departments; and

– innovation value – considers the value of gaining and sustaining competitive advantage, whilst calculating the risks or cost of being a pioneer and of the project failing.

Business domain assessment comprises staff and business units that utilize IT. Value is based on improved business performance. Thus, the concept of value has to be expanded within the business domain:

– strategic match – assessing the degree to which the proposed project corresponds to established corporate goals;

– competitive advantage – assessing the degree to which the proposed project provides an advantage in the marketplace;

– management information support – assessing the contribution towards management information requirements on core activities;

– competitive response – assessing the degree of corporate risk associated with not undertaking the project; and

– project or organizational risk – assessing the degree of risk based on project variables such as project size, project complexity and degree of organizational structure.

Technology domain assessment reviews the technological risks associated with undertaking a project:

– strategic IS architecture – measuring the degree to which the proposed project fits into the overall information systems direction;

– IS infrastructure risk – measures the degree to which the entire IS organization needs and is prepared to support the project;

– definitional uncertainty – assesses the degree to which the requirements/specifications of the project are known; and

– technical uncertainty – evaluates a project's dependence on new or untried technologies.

The model dictates a number of components in the analysis of an investment decision. The combination of the enhanced return on investment, business domain assessment and technology domain assessment provides a comprehensive look at the IT investment across business needs and technological abilities. It is manifestly a model capturing some necessary complexity, and factors commonly neglected. Consequently, however, it can be difficult to implement. The learning point from two respondent organizations – a retailer and an insurance company – which have utilized information economics is that its primary purpose should be to encourage debate across the managerial layers and functions and provide heightened understanding of the risks, costs and benefits associated with different IT investments. In this respect, building any scoring system around the framework works, as long as the process of evaluation is regarded as more important than its quantified result which necessarily is a mix of subjective judgements.

Balanced scorecards

The balanced business scorecard (examined in greater detail in Chapter 5) provides a well-rounded approach to evaluation by taking into account not only financial measures but also measures related to customer satisfaction, internal organizational processes, and organizational learning and growth. For now, let it suffice to say that the use of the comprehensive set of scorecard measures applied to investment feasibility could identify otherwise ignored costs and benefits. GenBank, for example, found the scorecard useful to the initial feasibility assessment process as a reminder of the types of costs and benefits that should be considered (see Chapter 5 for the detailed case study).

3.8 Benefits management: feasibility stage

Benefit management should be pursued across the life of any IT/e-business project. It is in the feasibility stage, however, that benefits are initially identified, making feasibility crucial to the success of the entire project and application portfolio. Benefit identification and quantification are, based on the findings of our research, two very difficult tasks at the heart of the evaluation dilemma. More specifically, it is probably the range of ‘intangible benefits’ that complicate all discussions of benefits. Intangibles include improved customer service, development of systems architecture, high job satisfaction, higher product quality, improved external/internal communications and management information, gaining competitive advantage, cost avoidance, avoiding competitive disadvantage and improved supplier relationships. Although the literature is rich with benefit measurement/identification concepts, we will focus here on two benefit management approaches that have proved particularly useful and that translate easily into the e-enabled world.

The benefits management process: Ward and Griffiths (1996)

Earlier in this chapter, Ward and Griffiths’ application portfolio classification was identified: support systems, key operational systems, strategic systems and high potential systems. This classification system can be used not only to examine the application portfolio, but also to identify the classes of benefits that might be available. Figure 3.5 provides a summary.

Figure 3.5 Generic sources of benefit for different IT applications

Ward and Griffiths reiterate what we have confirmed so far, namely that ‘there is no point in any sophisticated system of investment evaluation and priority setting unless the “system” is examined in terms of whether or not it delivers the business improvements required’15. The matrix shown in Figure 3.5 provides a rough idea of the types of benefits that might be identified and quantified. Effectively, an organization should quantify benefits as much as possible at the outset then, over the life of the project, continue to measure the project's ability to deliver those benefits. Ward and Griffiths suggest five interactive stages in benefits management. This is represented by Figure 3.6.

The stages pertinent to planning and prioritization and investment evaluation are as follows.

(1) Identification and structuring of benefits. This is the first stage of assessing the reasons for embarking on application development. The process of identifying target benefits should be an iterative one, based on on-going discussions about system objectives and the business performance improvements to be delivered by the system. Each identified benefit should be expressed in terms that can be measured, even if the measures are subjective ones such as surveys of opinion.

Figure 3.6 Process model of benefits management (source: Ward and Griffiths, 1996)

(2) Planning benefits realization. This is the process of understanding the organizational factors that will affect the organization's ability to achieve the benefits. It is basically a process of obtaining ownership and buy-in from the appropriate parties. If an organization cannot create a plan for a particular benefit, the benefit should be dropped.

The other benefits management stages (executing the benefits realization plan, evaluating and reviewing the results, and identifying the potential for further benefits) will be examined in Chapter 4. While Ward and Griffiths’ benefit management approach obviously crosses the line of feasibility investment into project management and post-implementation assessment, it is important to note it here along with feasibility assessment because, as mentioned, the initial identification and quantification of benefits is critical to success.

Benefits management examples

While these frameworks seem theoretical, all have been utilized to advantage in operating organizations in both the private and public sectors. Case study organizations revealed a variety of approaches to, and understanding of, benefits management. The potential usefulness of the frameworks can be read into the following scenarios.

– A large-scale UK-based retail organization was struggling to institute benefits comprehension throughout its organization. After following a mainly financial focus in evaluation for many years, the company attempted to refocus business performance measurement as it relates to IT. During feasibility assessment, the IT organization was attempting to classify benefits in a more standard manner, and to instill an understanding of benefits across the organization. In the late 1990s it identified four benefit categories: hard costs, enablers, migration (’have to's’) and intangibles/non-financials. The IT group established a Systems Investment Group in a fresh attempt to provide emphasis on the investment evaluation process. This group of cross-functional senior managers was made responsible for understanding IT costs, identifying business needs and their link to the business strategy, and selecting the appropriate investments to satisfy those needs. This group was to be a conduit for benefits comprehension for IT investments within the organization.

– In recent years, Sainsbury PLC's attention to the planning and IT investment assessment process has been marked by the attitude that IT is an investment rather than a cost. Sainsbury, the second largest food retailer in the UK, has discovered the difficulty associated with identifying and measuring benefits related to the implementation and use of technology. As a senior manager noted:

That's a big profit return, but you'll never measure it . . . For the 20 years up to about 1995 Sainsbury's had a fantastically successful formula that was highly repeatable. So the business plan was to repeat it as often as you could and profits grew by 20% compound per year for 20 years. And it was a fantastically successful business. What then happened was the opportunities to replicate that reduced and the competition caught up with what we were doing. And suddenly the businesses had to have a business plan of a more detailed nature to become a business plan that's truly trying to deal with the competitive edges rather than the competitive body. So we've not been in this position before. We are now, and it will be interesting to see how, as people go through this planning process, they make it happen in their processes . . . (and operations).

– In the late 1990s, Unipart, one of Europe's largest independent automotive parts companies, was using cash flow, payback, ‘real benefits’ in investment evaluation. Project proposals passed through UGC/IT then GEC, basically a group operating committee. The IT department had also developed a new measure of ‘proportion of customer IT spend used on strategic spend’ to drive good behaviour. According to Peter Ryding, Managing Director of Unipart Information Technology:

For a business application, we use cash flow and payback (for investment evaluation) . . . virtually all IT project investments have to be signed off by customers signing on to a real business benefit that it obtained. Ultimately payback is the word we tend to use more than anything else. Sometimes we go through where the financials don't add up, but we believe it's customer service and as a very customer service oriented business we are prepared to take the hit on that.

3.9 Summary

Risk assessment, planning and prioritization, feasibility evaluation and benefits management are key components of the lifecycle evaluation methodology, and, in fact, should be considered/revisited in all phases of that lifecycle. Feasibility evaluation is practised in some form by most organizations, although the evaluation emphasis tends to be financial in nature. The concept of benefits management, that of reviewing the delivery of benefits from an IT investment on an on-going basis, is a relatively new addition to the mix and, when applied effectively, provides a path through the financial bias of feasibility evaluation. Risk assessment, on the other hand, is often overlooked in the evaluation process, in spite of the overwhelming evidence that all IT investments have some level of associated risk that requires assessment and management.

Each of these evaluation components (risk assessment, planning and prioritization, feasibility evaluation and benefits management) have a number of techniques or approaches – no one technique in any category will satisfy all situations faced by an organization undertaking an IT investment. Consequently, care must be taken to match the technique best-suited to delivering the business objectives of a particular investment. In other words, potential investments should be reviewed in light of agreed organizational strategy. Moreover, at some point, investments should be reviewed collectively to identify synergies or discontinuities. As we saw in the case of Glaxo Wellcome, its piecemeal review of projects precluded a strategic view of the portfolio as well as obscuring its ability to control costs.

3.10 Key learning points

– The examination of failed projects presented in this chapter demonstrates the critical need to assess and manage risk. Chapter 4 details how measurement can assist in the process of keeping IT investments on track across the development, implementation and on-going phases of the system lifecycle.

– Risk assessment should take place on all projects/technology investments, as all will have some degree of associated risk. Risk assessment should ultimately provide part of the foundation for project management and measurement.

– Risk assessment requires the identification of risks, the estimation of impact of the risk and the on-going management of the risk.

– Risk identification, the process of proactively seeking out risks and their sources, and risk estimation must be the prelude to risk management. Risk identification can only diagnose and highlight risks, but this activity must lead to a risk management system which ensures that action is taken to mitigate those risks across the system's lifecycle.

– Risk management plans require resources. Resourcing will depend upon decisions about the trade-offs between how much risk aversion is required and how much risk can be accepted. Responsibility for risk aversion actions and the authority to take action are also determined in the resourcing phase.

– Models of risk assessment and diagnosis reveal a number of significant project variables to be managed from the perspective of risk mitigation, including:

(1) the need for user involvement;

(2) the level of commitment from management and key staff;

(4) on-going assessment of IT project alignment with strategy;

(5) a need to impose time constraints;

(6) attention to project size;

(7) the need for scope control;

(8) the inclusion of contingency planning; and

(9) the need for a feedback process from the measurement loop.

– Integrated project planning provides the focus for IT usage.

– With regards to planning and prioritization, the investment characteristics of IT highlight three factors to be included in the prioritization process:

(1) what is most important to do for the organization (benefits);

(2) what realistically can be accomplished (resources); and

(3) what is likely to succeed (risks).

In all likelihood, the constraint on IT investment will be available resources. Attention to this constraint will contribute to the concept of value maximization.

– The conduct of IT planning and investment feasibility is greatly influenced by management style and organizational culture. It is important to diagnose these with a view to assessing their appropriateness in terms of likelihood of supporting suitable IT evaluation methods.

– Users should participate in the feasibility assessment in order to assist in the identification of the benefits to the business of various alternatives, and to prevent the pursuit of technology merely for the sake of technology.

– Feasibility assessment should be carried out within the framework of lifecycle evaluation and is, in fact, a basis for ongoing evaluation.

– In spite of the difficulty in identifying and quantifying intangible business benefits, they must be examined as well as those that are tangible.

– Benefit identification methods should be matched to the objectives of the specific IT application. Inappropriate methods often overlook vital benefits.

3.11 Practical action guidelines

– View IT expenditures as investments.

– Proactively seek out risks and their sources, then manage those risks throughout the life of the investment.

– Aim to maximize the value delivered out of an IT investment from the resources available.

– Engage in strategic alignment between IT investments and business objectives.

– Prioritize resulting IT investments, also according to objectives.

– Include total IT costs in the budgeting process, including hardware, software, corporate support, data access, training and user costs.

– Match feasibility assessment and lifecycle evaluation techniques to prospective benefit types.

– Integrate the evaluation process across IT lifetime.

– Establish metrics at the strategic level, the business process/operations level, and the customer perspective level.

– Engage in organizational learning and establish metrics which enhance the pursuit of this capability.