Beyond Customer Led

Discontinuity and the Life Cycle

Customer as Value Manager

Customer Value Analysis

Scenarios

Gartner Magic Quadrant

Portfolio Analysis

Problems and Solutions

Dialectical SWOT Analysis: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats

Market Tipping

Corporate Strategy

Generic Strategy

E-Business Opportunity Matrix

Global Product Planning

Generic Network Strategy

Marketing and Communications Frameworks

Mass Customization: The Four Approaches

Attentionscape

Managing Customer Loyalty

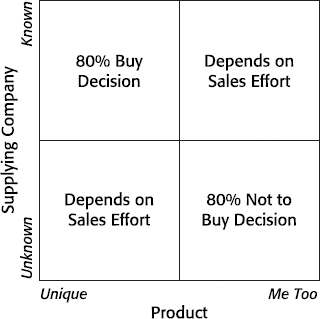

Likelihood to Buy

Revenue and Profitability

BCG: Product Portfolio Analysis

Uncertainty-Impact Matrix

Entrance and Exit Strategies

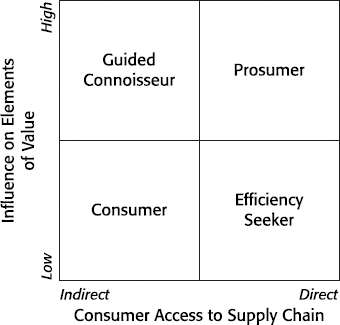

Strategy is the art and science of competing more effectively than one's competitors. The visible strategic act of corporate leaders is making choices that advance the goals of the firm in the best possible way. The more intense the competitive landscape is, the tougher the choices become. Great strategy making is, of course, more complex, subtle, and multifaceted than this.

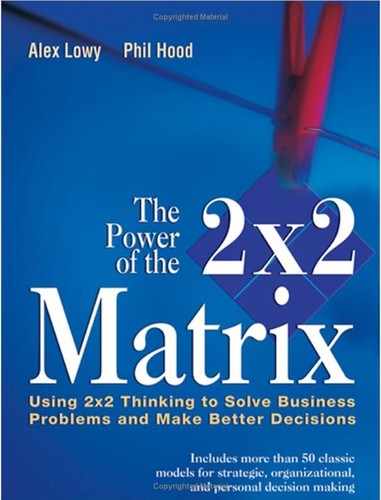

The key question the strategist seeks to answer is "How do we compete more effectively?" The archetypal strategic dilemma involves resolving the tension between Context and Value (Figure 6.1). Context is the who, why, where, and how of value creation; Value is the what. The job begins with defining the fields of inquiry in ways that naturally give rise to the right sorts of dialogue, learning, and, eventually, choices.

Note

The Archetypal Strategic Dilemma

Core Question: How do we compete more effectively?

Leaders establish constraints that frame future decisions. When Lewis and Clarke arrived at the fork in the Clearwater River on their long, arduous journey in 1805, the deliberation was framed as, "Which way should we go?" and not, "Should we go on?" Gandhi, in the early 1900s, chose the path of nonviolent protest, inspiring a nation and overpowering the endurance of the British Empire. First, he defined the strategic arena as how to achieve independence for India, and then he focused the issue as a choice of means: Would there be violence or not? Saul Alinsky, the ingenious 1960s guerrilla lawyer and advocate for social justice and change, laid strategic traps for uncooperative institutions. When disenfranchised residents in Harlem were refused credit from the local bank, he organized legions of supporters to tie the bank in nonproductive knots, lining up all day to deposit and then withdraw pennies at a time.[38] He defined the battlefield as an issue of access and then gave the bank problems much greater than that represented by fair access. He applied this social jujitsu time and again to champion the causes of his clients.

More often than not, effective definition of strategic issues and options is built on a dialectical foundation. Lewis and Clarke were torn between the leader's vision and the navigator's expert but incomplete advice. India, under Gandhi's guidance, pursued the tension between the right to self-determination and rule, and the maintenance of civility and progress. Alinsky played one interest (high-value clients, risk aversion) against another (community power expressed through system jamming and escalating embarrassment).

Viewed in this way, making tough strategic choices is really the final step in a more complex process. Gaining leverage lies in planning and controlling that process, arguably the most important thing a leader can do.

Modern business strategy practices can be traced to the work of Alfred Chandler and Igor Ansoff in the early 1960s.[39] Form follows function was the way Chandler framed strategy in his book Strategy and Structure. The how should derive from the what and why. Ansoff's seminal book, Corporate Strategy, focused on the strategic problem of a firm and presented a framework and language for strategic decision making. The now famous Product-Market matrix (see page 135) defined growth and diversification options in a way that planners could easily apply and communicate to others.

A generation of business leaders took the strategy credo to heart, and planning departments began to appear everywhere, creating detailed multiyear blueprints for their corporations. General Electric's strategic planning office employed over two hundred senior-level staff in 1983 when Jack Welch disbanded it. Mintzberg's empirically based study of executive behavior, reported on in 1983, described what was really going on, emphasizing the dynamic, reality-informed, and iterative nature of strategy.[40] A more apt metaphor for strategy, it seemed, was course correction, and zigzagging rather than perfect planning processes yielding long-term blueprints.

The term strategic thinking replaced strategic planning in the late 1970s to reflect this need to sense and adjust to external reality on an ongoing basis. The best strategy making is done in context, on the fly. Mintzberg's leaders built strategy on the move. They thought strategically, grabbing moments in the hall, on elevators, and in conversations. Reflection and action define an ongoing learning process that is periodically expressed as strategy.

Competition shifted to warp speed in the 1990s, driven by the Internet and globalization. New rules were being written daily, as all semblance of predictability and permanence seemed to disappear in a shrinking and real-time world. Direct and inexpensive access to competitive intelligence, coupled with the rise of new inter-enterprise business models, redefined competitive practices. Being strategic replaced the development of long-term strategy, and businesses found it more helpful to refer to strategic contexts within which rolling three- and six-month plans were implemented.

Strategy making is recognized now as a dialectical dance between competing goals and modes; form and function shape each other; the organization is the strategy. Agility, an aspect of form, is recognized as key to strategic effectiveness; market share and profitability compete for primacy, and growth and stability oscillate in self-correcting loops.

Strategy is inherently dialectical in nature, and so it is no surprise to find a wealth of important and useful strategic 2 × 2 frameworks. The frameworks in this chapter are organized into five categories:

Customer needs. Customers are the ultimate arbiter of any strategy. Businesses have devised elaborate surveys and focus group methods to help them get inside the customer's head and understand her experiences and motivations. The frameworks in this section address the challenge from an assortment of useful and creative angles.

Strategic context. Business success is as much a function of external factors as the actions undertaken by a firm itself. Strategic context includes such considerations as the nature of competition and the timing of an offering.

Strategic options. The essence of strategy lies in defining a value proposition and creating the competitive plan. This group of frameworks helps to generate a rich set of possibilities and sort them in an efficient and meaningful way.

Marketing and communications. Brand development and positioning are critical competitive factors, determined largely by how a firm presents itself and communicates its value. Businesses need to know how they are perceived in the marketplace and what they are seen to stand for.

Risk management. With competition and reward comes risk. Businesses must get clear about the value of the prize, the costs involved in trying to succeed, and the possibility of failure. This set of frameworks helps to make risk decisions more explicit and rational.

What is in the minds and hearts of our customers? How do they view us? How will their needs evolve? Who else might become customers?

The success and renewal of a firm's value proposition begins in the marketplace with customers. In the past decade, power has been migrating steadily away from firms to customers, riding on the wings of readily available knowledge. Proactive customers know what they want, and they seek out suppliers who will deliver to their satisfaction. Paying attention to customers' needs and experiences is common sense and good business. The cost of acquiring a new customer can easily be several hundred dollars. Retaining customers doesn't need to be an expensive undertaking, with the added bonus of learning more about how to do your business better.

The public does not know what is possible, but we do.

As much as anything, foresight comes from really wanting to make a difference in people's lives.

To Hamel and Prahalad, innovation and the ability to challenge one's own practices and assumptions are necessary core competencies for the successful 21st century corporation. Successive waves of organizational improvement tend to play within existing boundaries and do little to shape markets in helpful ways. Corporate restucturing and reengineering are two major sets of initiatives that lower costs and improve efficency but ignore core issues of value definition and renewal. Hamel and Prahalad's work represents a healthy and invigorating reaction to hierarchical strategic planning, encouraging everyone to be more proactive in recognizing opportunities, innovating, and making their own work more meaningful. Their message is delivered in award-winning Harvard Business Review articles like "Strategic Intent," books like Competing for the Future and Leading the Revolution, and the work of Strategos, the strategy consulting firm that Hamel heads.

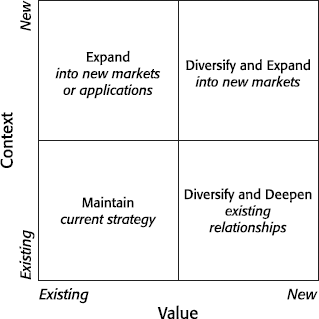

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Beyond Customer Led matrix (Figure 6.2) explores the two dimensions of Needs and Customers:

Needs. Businesses pride themselves on understanding their customers and their evolving needs. Most methods, however, provide insight into those needs that customers recognize and can express as a wish or a gap. The Needs dimension defines this condition as one end of a continuum, with unknown, unarticulated needs as the counterpoint.

Customers. Two classes of customer are important to a business: those it currently serves and those it does not.

The Four Quadrants. Companies can meet the known needs of existing customers, or they can venture further into new and promising areas of potential and future needs. The Beyond Customer Led matrix identifies four possible need groups:

Upper left: Unarticulated-Served. A satisfied customer today may become frustrated or uninterested if his unexpressed but felt needs are not addressed. This set of needs represents a rich opportunity for reinvention, value extension, and learning.

Lower left: Articulated-Served. This is the known world of customer needs. Although it is crucial to care for these signals, there is limited innovation potential here, and companies need to be careful not to lose sight of what is evolving in their efforts to be responsive.

Lower right: Articulated-Unserved. Offerings developed and perfected for existing customers can be extended to new customers in different markets. Like the upper left quadrant, this space describes a prime and natural strategic opportunity zone.

Upper right: Unarticulated-Unserved. Getting inside the heads and experiences of unaddressed customers is the last frontier of customer need identification. As remote as this may sound, it is exactly what proactive and visionary companies like Honda have done to fuel their remarkable expansion over the past two decades.

Example: The Chrysler Minivan. In the 1950s, U.S. automobile production accounted for two-thirds of the world total. By the 1970s, that number had been cut to 23 percent due directly to the growing strength of its offshore competitors in Japan and Europe. The oil crunch of the 1970s added to the problem, leaving thousands of gas-guzzling sedans sitting in Detroit plant parking lots while consumers flocked to buy fuel-efficient cars from overseas.

In the early 1980s, Hal Sperlich was working at Ford to develop what would become the now ubiquitous minivan. When he couldn't convince Ford this was a good idea, he left to join Chrysler. The rest is history.

The North American automobile companies were losing market share for a number of good reasons. Built for volume production, their assembly lines and factories were costly and inflexible. A disaffected workforce was more concerned with protecting labor gains than making their companies innovative and more competitive. Probably most worrisome, competitors' cars were outperforming theirs, using new lean manufacturing methods that were almost impossible to apply in older car plants.

The cost structure and underlying business model of the North American companies made innovation nearly impossible, yet this was precisely what was needed to revitalize the sector. When Sperlich launched his campaign within Ford, it ran afoul of both the strategic thrust and the company executives, eventually leading to his being fired. "[Ford] lacked confidence that a market existed, because the product didn't exist. The auto industry places great value on historical studies of market segments."[43]

Demographics painted a clear picture of the coming period. Relatively affluent and growing North American families needed larger interior car space. They just didn't know they did because nothing like the minivan yet existed. The minivan provided that extra bit of space that made trips to the cottage more comfortable, hockey equipment easier to cart around, and home repairs less painful (Figure 6.3).

The Beyond Customer Led matrix shows how unarticulated needs can be used to inform strategic vision and ultimately help redirect investments. "In 10 years of developing the minivan we never once got a letter from a housewife asking us to invent one. To the skeptics, that proved there wasn't a market out there."[44]

Sperlich's innovation and Chrysler chairman Lee Iaccoca's vision and courage were instrumental in pulling Chrysler out of a desperate decline. When the MPV model was launched in 1983, it sold more than half a million units, helping right Chrysler and overnight creating a new car category.

Context. Beyond Customer Led is ideal for strategic planning and product-service reinvigoration. This is a simple and powerful way to tap creative thinking within a firm and in dialogue with partners and customers. It is also a useful device for auditing future plans once they have been developed by asking questions from the perspective of each of the four needs groups—for example, Will these plans meet the known needs of existing customers?

Method. There is a highly intuitive feel to applying this framework as a tool. The process works best as a creative search exercise, responding to a set of questions which elicit content for each of the quadrants. Once this is done, patterns in needs and opportunities can be identified. This tool works well for individuals and teams:

Step 1: Make incremental improvements. Looking at the lower left quadrant, ask the following questions: How well are we responding to the articulated needs of our customers? Are there innovative ways we could improve on meeting their needs?

Step 2: Anticipate needs of existing customers. Looking at the upper left quadrant, ask the following questions: What do we know about our current customers that suggests additional needs we are not addressing? How will our customers' situations change over the next five to ten years? What needs will these changes create that we might respond to?

Step 3: Meet known needs of new customers. Looking at the lower right quadrant, ask the following questions: Which of our offerings have the greatest portability to new settings and customer segments? Which new markets are most attractive and well suited to our offerings?

Step 4: Explore needs of noncustomers. Looking at the upper right quadrant, ask the following questions: Which new markets are most appealing to us? What would be useful to know about them? How might we go about learning more about their needs? What needs exist beyond the obvious ones?

Step 5: Review. Having answered these questions, step back from the matrix and look for patterns of opportunity. What are the most unusual ideas? Which ones are the best fit with your firm's competencies?

Hamel, G. Leading the Revolution. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000.

Hamel, G., and Prahalad, C. K. "Strategic Intent." Harvard Business Review, May 1989.

Hamel, G., and Prahalad, C. K. Competing for the Future. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1994.

You may think you're in the high-tech business—software, hardware, networking, services, biotech, whatever. In fact, you're in the discontinuous innovations business. Which means you're in the most risky business on earth.

Dramatic improvements in end-user capabilities, then, are the accelerator that drives technology adoption, just as paradigm shock is the brake.

The technology adoption life cycle, developed at Harvard University in the 1930s, originally described the pattern and rate of acceptance of new seed potatoes in the U.S. Midwest. Shaped like the typical bell curve, it elegantly mapped how a new technology grows from an experimental notion to a widely used commodity. As a technology matures and becomes less risky, different groups of customers, each with a distinct set of characteristics and needs, adopt it. The earliest adopters are technically oriented, with genuine interest in the product features. Later buyers tend to be pragmatic and conservative, and care most about business benefits resulting from the technology's use.

Geoffrey Moore expanded on the cycle in his 1991 book, Crossing the Chasm, describing what occurs when the technology is discontinuous and disruptive. In these cases, as was true for many of the Internet companies in Silicon Valley when Moore wrote his book, successful movement through the cycle involves bridging a set of gaps. Color TVs and laptop computers are continuous technological improvements, drawing on preexisting infrastructures and user skills. Wireless computing and electric cars are discontinuous and demand greater patience, investment, and learning while the technology becomes fully functional and supported by manufacturers, servicers, and standards. Not all new technologies successfully cross the chasm between the early experimenters and the more risk-averse majority buyers.

The book became a marketing bible for information technology companies during the supercharged 1990s, and Moore's Chasm Group was called on to guide hundreds of entrepreneurial ventures through the technology adoption life cycle. Discontinuous technology is by definition a risky business, and Moore's modeling offered structure, principles, and method to convert innovation into profitable business. Begin by understanding where your technology fits in the adoption cycle, focus on the right customers for the stage you are at, and deliver value that responds to current needs and interests. Strategy and communications change dramatically as a technology matures and one audience is replaced by the next.

The Discontinuity and Life Cycle framework (Figure 6.4) is the core tool employed by the Chasm Group for strategic diagnosis and market planning, integrating the cycle with market forces and customer types. Although this framework describes the world of discontinuous technologies, the method and lessons are relevant for most businesses involved in launching new products.

The Discontinuity and Life Cycle matrix is a highly integrated planning tool that communicates three sets of information: the technology adoption life cycle, the customer audiences being served, and the forces driving and restraining market adoption. At first glance, the picture may appear complex; however, each of the three sets of information is valid, relevant, and intuitively clear. The key to deciphering the map is to follow the life cycle, which moves in a clockwise direction starting in the upper left quadrant.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. Two kinds of discontinuity shape the technology adoption life cycle: Paradigm Shock and Application Breakthrough. It is helpful to think of these forces as variations of Cost (Paradigm Shock) and Benefit (Application Breakthrough):

Paradigm Shock (Pain). Paradigm Shock measures the amount of adjustment required by end users and infrastructure providers to use the new technology. When this is too high, as it often is in early phases, people are more reluctant to invest. Electric cars are expensive and demand considerable investment and learning on the part of owners, mechanics, and gas stations in order to perform adequately. This pain dampens enthusiasm and the willingness to purchase, save for the most enthusiastic buyers.

Application Breakthrough (Gain). Application Breakthrough is the gain derived through use of the new technology. Potential users become motivated to sign on as the ability to benefit rises. Often there is a noticeable threshold that must be reached before a larger mass audience recognizes the merits of the new technology and pursues it. Faxes and cell phones are examples. In the case of electric cars, the benefits of ownership need to outweigh the costs for the technology to move to a state of mass adoption.

The Four Quadrants. The four quadrants in this model help to organize and align key elements of a marketing strategy:

Upper left: Prototypes. Life cycles begin here, built on ideas with potential rather than practical things. At this stage, pain and adjustment tend to be high, and tangible benefits are low. This is the world of pure science and prototypes, where users are tech-savvy enthusiasts.

Upper right: Early Market. A limited Early Market is led by one or several visionaries who recognize the potential of the new technology and support its development through funding and leadership. The first application breakthroughs are made in this phase, attracting the interest of more pragmatic customers. The challenge of this period is to demonstrate the potential value of the innovation in a convincing enough manner to recruit customers willing to experiment with it in their organizations. The Chasm, which lies between the Early Market and the Bowling Alley, can last for an extended length of time, effectively blocking mainstream adoption. Anticipating and planning for this time lag is critical.

Lower right: Bowling Alley. New technologies must be proven in smaller niche-like environments before broad uptake can occur. This is like targeting specific bowling pins, with momentum and impact increasing as successive pins are knocked over. To accomplish this, the supplier must gain a full understanding of the specific issues facing the target business and deliver a complete end-to-end solution. This is an incremental strategy phase, where success with one or two players in a segment leads to additional competitors' getting on board. If one or two industries can be won over, interest and credibility rise, and infrastructure requirements for mass adoption begin to be met.

Lower left: Main Street. Maturation of basic infrastructure and the emergence of standards fuels what Moore calls the Tornado. In Tornados, demand accelerates significantly as the product moves from niche to generic. Buyers tend to be technical as companies recognize the benefits and want to integrate the new technology as quickly as possible. The key to winning in Tornados is being part of the dominant solution or platform, staying focused on the core offering, and meeting the demand in a reasonable enough time frame.

Example: Winners and Losers in the PC Industry. The early years of computing were dominated by IBM, which at one point accounted for almost 80 percent of computer-related revenues worldwide. As the computing paradigm switched from mainframes to minis and PCs, a new generation of hardware, software, and services companies entered the scene, redefining the market. Out of this competitive chaos, two companies emerged as winners: Microsoft in software and Intel in the microchip market. In 1993, Intel took 50 percent of the total profit earned by the top 150 high-tech companies in Silicon Valley and by 2003 had a market value approaching that of IBM. Microsoft's market value is roughly twice that of IBM.

Organized first around the DOS operating standard and subsequently around the now ubiquitous Windows, the pair has dominated the computing world and benefited disproportionately from waves of innovation and the ever-growing number of users. How Microsoft and Intel achieved this success and continue to exercise such influence is made apparent by the discontinuity and life cycle analysis (see Figure 6.5).

Until the late 1970s, computing was principally the domain of specialists and hobbyists. Computers were expensive, large, and complicated. Interacting with them required learning elaborate programming languages. Prototypes of faster, smaller computers were being tested, but materials, design, and usage barriers kept all but the keenest enthusiasts away.

This all began to shift in the 1970s with the introduction of smaller minicomputers and desktop personal computers. The revolution was under way as visionaries at Bell Labs, Apple, and a few other places designed personal computers that were functional and held the promise of applicability to a wider audience. At the core of the new machines was a small, affordable microprocessor that enabled miniaturization and an operating system that was more intuitive and human-friendly.

To get through the first Chasm organized around the DOS operating system, the Wintel coalition contained a host of strategic partners, including Lotus for its spreadsheet software, MicroPro's Wordstar word processor, HP for printers, Conner for hard disk drives, and Novell for a network operating system. As these firms came together to deliver a complete working system, the Bowling Alley strategy quickly accumulated the energy needed to launch a Tornado that would lock in whole markets to the new systems and standards, with Microsoft and Intel at its center. The key to unleashing the Tornado was the flood of applications that independent software developers created to support the common platform. The move to Main Street occurred once technical and cost barriers had been removed and the infrastructure was solid.

The cycle was repeated again in 1991, but more quickly, when the Windows operating system was introduced. This time, fewer partners were included in the core coalition. Intel remained with its 486 and Pentium chips, as did HP, but Microsoft took the opportunity to integrate its own word processing package, Word, and spreadsheet application, Excel. One of the lessons of Tornado marketing is that markets want to deal with the fewest number of vendors organized around standard offerings. The outcome, as we know, is that the Microsoft Office suite of applications quickly became the desktop standard, much as Windows was the dominant operating system.

Margins compressed as these products matured and found their way onto Main Street, but market size increased exponentially. In successive mini-waves of innovation, additional partner functions have been integrated into the core set, like Novell's network operating system. However, by providing a standard, they have been able to preserve their role, adding improvements and cutting costs to stay ahead of the competition.

Context. The framework is applicable to strategy and marketing efforts of businesses where innovation and technology development are central to success. Each phase of the technology adoption life cycle has a unique set of requirements and opportunities, and it is dangerous and wasteful to be working from the wrong starting point.

Method. The object is to gain market acceptance in the quickest and most effective manner. While accuracy of analysis is important, the first critical task is to align the business leadership team around their assessment of the phase of development of the technology category to which the innovation belongs:

Step 1: Diagnose. Determine where the technology category lies on the technology adoption life cycle.

Step 2: Move out of the twilight zone. At any point, the market adoption process is at risk of losing steam and being marooned. New technologies cannot survive these for very long, and it becomes a priority to break loose. The two levers are reducing Paradigm Shock and increasing Application Breakthrough benefits.

Step 3: Move to the next stage. Strategies exist to advance successfully to the next stage. For example, Early Market entry requires finding visionaries and defining high-payoff development areas, while Bowling Alley entry depends on careful segmentation and understanding industry-specific challenges.

Moore, G. Crossing the Chasm: Marketing and Selling High-Tech Products to Mainstream Customers. New York: HarperBusiness, 1991.

Moore, G. Inside the Tornado: Marketing Strategies from Silicon Valley's Cutting Edge. New York: HarperCollins, 1995.

Wiefels, P. The Chasm Companion: A Fieldbook to Crossing the Chasm and Inside the Tornado. New York: HarperBusiness, 2002

It's a new imperative; businesses need to design their processes in ways that allow customers to drive value creation.

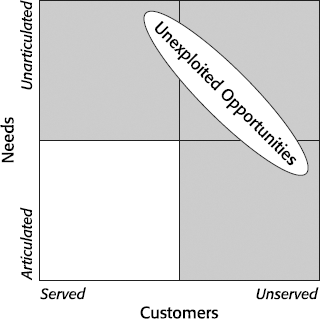

What does it mean to develop a customer-driven fulfillment network? The concept of the customer as value manager (CVM) comes from a multimillion-dollar research project into the future of supply chains conducted by Digital 4Sight in 2000. It explored how companies use information technology to support sales and let individual customers design those parts of the product or service experience that matter to them. There are great variations in the degree to which customers want to play an active role in processes related to product design, configuration, sales, delivery, and support. Some prefer to act through intermediaries; others want to buy on-line. Some care about product configuration; others are concerned with fast delivery. The model encourages companies to think in terms of enabling customers to access only those parts of the supply chain that add value for them (Figure 6.6). When we view customers as value managers, we present them with an individualized supply chain that perfectly fits their needs. Ideally, we isolate and emphasize supply chain capabilities to meet customer needs rather than the needs of mass production.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The CVM model differentiates customer groups by the degree to which they actively participate in offering design and by the way they access supply chain activities:[48]

Influence on Elements of Value. Influence refers to the degree to which customers want to have a voice in the design and customization of products and services.

Customer Access to Supply Chain. Customers interact directly (using information systems) with supply chain activities or through intermediaries. Consider the case of a company selling business furniture. Customers might prefer to purchase through an intermediary such as an architect, space planner, or retailer, or they might choose to buy directly from the company.

The Four Quadrants. The model segments buyers by their purchasing preferences rather than by demographic or economic characteristics:

Upper left: Guided Connoisseur. The Guided Connoisseur is a serious customer who is experienced in dealing with intermediaries—architects, space designers, retailers—and expects a high level of choice and customization. One way to reach the Guided Connoisseur is through on-line tools that can be shared by them and their chosen intermediary. This is commonly done in the building industry.

Lower left: Consumer. The Consumer segment is happy to buy standard products through existing channels. In our corporate furniture example, this might represent a corporate customer who lets a space planner make all furniture decisions.

Lower right: Efficiency Seeker. The Efficiency Seeker wants to control the buying experience and is prepared to accept a limited role in designing product specifications. This might be an executive in a fast-moving start-up who wants to be able to go on-line to manage his account and is more concerned with convenient financing, quick delivery, and service than in an expanded selection or product customization.

Upper right: Prosumer. The Prosumer is a sophisticated customer who wants both high customization and direct access. This buyer is comfortable dealing through the on-line channel and doesn't want the transaction overhead of retailers and agents.

Method. Follow these steps to conduct a Customer as Value Manager analysis:

Step 1: Assess the offering. Make a short list of the critical features of your product or service offering viewed from the customer's perspective. You may include elements such as style, price, delivery terms, selection, and financing.

Step 2: Assess customers. Make a list of your major customer groups and identify individual customers within these groups. This will help you think about where to place them on the matrix.

Step 3: Diagnose. Place customers into the four quadrants based on the extent to which they need to influence and manage value. Refer to the list of features identified in step 1 to evaluate customer preferences.

Step 4: Design. Define strategies to provide customers with their preferred form of access.

Tapscott, D., Ticoll, D., and Lowy, A. Digital Capital: Harnessing the Power of Business Webs. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000.

Winning customers by providing superior quality attracts customers who are inherently more loyal.... By contrast, customers who instinctively buy on price, or are trained to buy on promotions, tend to wander from supplier to supplier looking for the one who is most desperate.

Are your customers satisfied with your current offerings? Do you know why they are satisfied? Is it because of your price or your value? And even if they report that they are deeply satisfied, under what conditions would they switch to a competitor's product or service?

These are questions that marketers find difficult to answer. Customer satisfaction surveys are helpful, but only fill in part of the picture. Customer Value Analysis (CVA) is a powerful tool that reveals how specific product attributes contribute to customer perception of value and the buying decision. It enables one to focus on the aspects of product or service that are most likely to increase customer acquisition, retention, and profitability.

The branch of economics that is concerned with how consumers make decisions is called utility theory and has its roots in the work of economist Jeremy Bentham in the late eighteenth century. Modern Customer Value Analysis is the result of work done by Bradley Gale and others at AT&T in the 1980s. A generally satisfied customer, they found, does not necessarily produce repeat business or improved financial results. The CVA principles and method described in Gale's 1994 book, Managing Customer Value, were created to get at the critical drivers and interdependencies influencing customer buying decisions (see Figure 6.7).

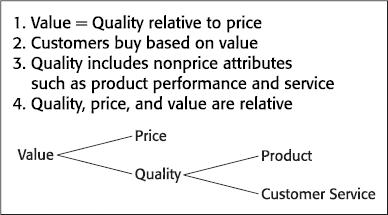

Customer Value Analysis is built on the proposition that customers choose among suppliers based on perceived value. Value (Figure 6.8) is a combination of price and quality. Lowering the price or raising the quality of a product will improve its overall perceived value relative to competitors' products (provided, of course, that such information is communicated convincingly to potential customers).

Customer Value Analysis is a two-step process. First, measure how customers perceive the quality and price of your products versus those of your competitors. Then plot these data on a Customer Value Map. Firms that are perceived to be lower in price and higher in quality than competitors are poised for market share gains. Conversely, a low score in either or both of these measures is cause for concern. The fair value line indicates where quality and price are in balance. Gale uses the terms "Customer-Perceived Price" and "Customer-Perceived Quality" (or "Market-Perceived Quality") to reflect that the profiles are determined principally by gauging customer perceptions.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Customer Value Map explores two key dimensions: Customer-Perceived Price and Customer-Perceived Quality:

Customer-Perceived (Relative) Price. Customer-Perceived Price reflects all relevant components of price. For homes, this might include financing costs, maintenance, local real estate taxes, and expected appreciation, as well as the initial purchase price. If you were shopping for steaks, purchase cost would be the only relevant price.

Customer-Perceived Quality. Perceived Quality includes all product attributes other than price. Different attributes are relevant in each product category. Home buyers might consider location, materials, style, size, landscaping, and other factors. In the steak example, quality perceptions might focus on such attributes as color, marbling, freshness, brand, government inspection, and convenience of purchase.

The Four Quadrants. Each quadrant (Figure 6.9) corresponds to a general relative value and suggests a particular action. The fair value line sits at a different angle for different product categories. For example, in luxury goods, a small quality improvement may justify a large price differential. However, for commodities, consumers may be indifferent to quality differentiation, suggesting a more horizontal fair value line:

Upper left: Worse Customer Value. Customer preferences shift in economic downturns, and higher-priced products often find themselves in this position. The recession of 2000–2003 contributed to the demise of the Concorde as wealthy travelers decided to cut back on its pricey transatlantic flights in favor of cheaper air travel.

Lower left: Commodity Value. Goods in this quadrant are commodities with little differentiation between vendors. As a result, the products tend to sell on price. Many raw materials and agricultural products are sold as graded commodities. The price a seller of copper receives is typically the same as the price every other seller receives.

Lower right: Better Customer Value. Products in this category are perceived as value leaders; costs are competitive, and the products possess the quality attributes that customers value most highly.

Upper right: Unique Value. This quadrant is populated by upscale goods and services that offer Unique Value. Examples include high-margin products such as custom jewelry and entertainment experiences for which close substitutes are not available.

An area chart of customer value, sometimes called a defection-acquisition index (Figure 6.10), is used to gain insight at a more granular level into factors influencing customer decision making. Each horizontal bar represents an attribute or feature, such as style, service, or image. Ratings to the left of the bar indicate that a company is perceived as performing worse than its competition, making it vulnerable to customer defection. Ratings to the right indicate it is perceived as better than the competition, suggesting opportunities for customer acquisition.

In addition to targeting product and service investments into areas that will have the greatest impact on ability to win and retain business, the area chart also is useful in identifying areas of potential investment or cost savings. For example, if it is expensive to improve feature 1 but relatively easy to improve feature 3, the firm could gain the most customers for the least dollars by focusing its investments on feature 3. This type of modeling is also sometimes referred to as performance impact analysis.

Example: Denim Jeans. Let's use a hypothetical example based on recent events. In the denim jeans market of recent years, Levi's has consistently lost market share, falling from $7 billion of revenue in 1996 to $4.2 billion in 2001. It lost business on the high end to more stylish and innovative competitors such as Calvin Klein and fashionable upstarts such as Diesel. Conversely, it lost low-end business to companies such as Arizona Brands. For much of this period, Levi's was heavily dependent on U.S.-based manufacturing and couldn't compete on price with offshore competitors. In such a situation, one can well imagine that existing Levi's customers might respond positively on a traditional customer satisfaction survey, but still purchase a different brand. A customer value analysis can provide insight into the situation.

The key components of quality in a pair of jeans might include materials, cut or styling, availability, peer group approval, and advertising. The hypothetical CVA analysis in Figure 6.11 shows that although Levi's is lower priced than many competitors, it is still on the wrong side of the fair value line. Merely cutting the price is unlikely to right the fair value equation. Instead, Levi's needs to change the product or the perception of the product, or some combination of the two. Deeper analysis of customer value on a feature-by-feature basis may reveal that Levi's invests too much on some attributes of the product and not enough in others.

Method. An in-depth CVA implementation requires marketing research skills and familiarity with statistical analysis techniques described in Gale's book. Many consulting companies specialize in Customer Value Analysis as a specific offering. For a general introduction to the method, we suggest trying the following exercise. If customers are not easily available for surveying, have your sales teams rate the products and those of the competition.

Step 1: Define. Develop a list of competitors and products to which you wish to be compared.

Step 2: Research. Develop quick market-perceived price and quality profiles by asking customers what attributes they consider in making a purchase. Then ask customers to weight the attributes by distributing 100 points among them. Create the price and quality ratios (the method is described immediately after step 3).

Step 3: Summarize the implications. Using the market-perceived quality ratios, identify and discuss the defection and acquisition implications of your analysis.

Creating a Quality Profile. There are three steps to creating a quality profile:

Determine the attributes of product quality that influence purchases.

Survey customers to determine how your offering is perceived relative to that of your competitors.

Weight the scores to derive a quality ratio.

The simplest way to determine the components or attributes of quality is to ask a group of survey subjects what they believe they are. Then ask them how you and your competitors rate on each attribute of quality. (It may also be useful with some products to gather information from secondary sources such as research firms to objectively define product performance. For example, if you were comparing motorcycles, you might factor in objective data about performance and handling or warranties.) Next, ask them to weight each quality attribute by dividing 100 points among all of the attributes based on their relative importance in the overall purchasing decision. A market-perceived quality ratio is then created by multiplying each competing product's score by the weight of the factor.

Table 6.1 contains a sample quality profile. Company A surveys handbag buyers to find out which features are most important to their purchasing decisions. It discovers that there are three key features: materials, style, and brand image. Company A also finds that although purchasers rate it above competitors in terms of materials and brand image, they rate it at the same level with competitors on style. This is important because style is the product attribute that customers rate as most influential to their buying decisions. The overall weighted ratio is 115.375 (a score of 100 indicates relative parity with competitors), indicating the company is well positioned versus competitors in terms of perceived quality.

Creating a Price Profile. Perceptions about the costs of purchasing and owning a product can be as important as actual price in influencing purchases. This is especially true in the case of expensive products such as cars, where the anticipated costs of maintenance, financing, and the gain or loss through resale value figure prominently. To capture this information, price profiles are calculated based on customers' perceptions of the cost of components that constitute the total price of a particular good (Table 6.2). Weighting these components produces a market-perceived price ratio, similar to the quality ratio.

Table 6.1. Customer-Perceived Quality Profile

Market-Perceived Quality Ratios | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Quality Attributes | Importance Weighting | Company A | Competitors | Ratio Company A/Competitors | Weight Times Ratio |

Materials | 25 | 8 | 6 | 1.33 | 33.25 |

Style | 50 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 50 |

Brand image | 25 | 9 | 7 | 1.285 | 32.125 |

115.375 | |||||

Once price and quality ratios are completed, the outcomes are plotted on a Customer Value Map that compares perceived quality and price points for a company and its competitors. Points on the map correspond to each company's relative performance in terms of overall quality and overall price. At any point on the fair value line, a company should neither lose nor gain market share.

What external trends and factors need to be considered? How will they affect choice of strategy? What impact will they have on implementation?

Strategy is relative. Like moves on a chessboard, the wisdom of a decision depends entirely on the placement of the other pieces as well as what is in the minds of the other players. Understanding the external context is always important, but it is most useful in two critical phases of strategy development: as input before a strategy is formulated and as consideration during implementation.

There are many different approaches to context analysis. One can focus on the future, the market structure, competitors, trends, and other features of the competitive landscape. Often firms contract this task out to a consulting or research partner to ensure they receive an unbiased view. However, you can also learn a great deal simply by sampling different strategic context models. Each of the frameworks in this section offers a different way to profile the competitive landscape and is worthy of consideration. After reading a framework summary, invest five minutes to see what it tells you about your strategic needs.

Scenarios are not about predicting the future, rather they are about perceiving futures in the present.

The future is unknowable and therefore risky.[51] Traditional planning methods work well enough when the time frame is the next quarter or perhaps one to two years into the future. But beyond that, projections based on current reality are dangerously unreliable. Reality rarely unfolds in a linear fashion, and unpredictable events—wars, revolutions, scientific breakthroughs, stock market booms, natural disasters, and others—spoil the best-laid plans.

Scenario planning aims to reduce longer-term risk by creating imagined futures based on an appreciation of key forces driving social, economic, political, and technological change. Companies, governments, and other large institutions create scenarios to make judgments about the future viability of current strategies and to explore areas of long-range concern that would never show up in a typical planning exercise. Many of the most useful scenario planning efforts adapt readily to the 2 × 2 form. We'll examine two of them in this section.

Scenario planning emerged as a serious business method at Shell in 1960s and 1970s where Pierre Wack led a group that developed scenario methods and anticipated the oil price shocks of 1973. Later, Wack, working closely with Willis Harman, Peter Schwartz, and other scenario developers at the Stanford Research Institute, refined the methods. Schwartz himself took over scenario planning at Shell, where he had the opportunity to improve the technique further, anticipating issues such as the fall of the Eastern bloc countries. In 1987, he and a group of visionary thinkers and writers, including Jay Ogilvy, Stewart Brand, Lawrence Wilkinson, and Napier Collins, formed the Global Business Network, a firm specializing in scenarios. Today, the technique is widely used in government, academia, and corporate planning exercises.

The goal of scenario planning is not to create the one right scenario. Rather, it is to create a set of viable options—robust scenarios that may hew closely to the future as it unfolds. Parts of each of the scenarios are likely to become manifest over time. To be useful, modeling needs to push limits so aspects of the scenarios are radical enough to encompass wild card events.

Choosing axes is the most critical step in scenario matrix development. Each axis must represent a dynamic force that is likely to be a defining feature of any future reality. Well-chosen axes create four plausible futures that help assess the risks of particular positions and strategies. Defining the axes frequently begins with asking questions that could have a great impact on the institution's future, such as, "What happens if economic growth slows down or increases greatly?" "Will social attitudes become more liberal or more conservative?" "Will raw material prices be stable or fluctuate greatly?"

We look at two examples here that illustrate the range and impact of the method: one on the future of automobiles and the other on libraries.

Example 1: The Future of Automobiles

This example was developed by the Global Business Network in the 1980s while working with an automotive company. The work influenced Detroit's thinking about the increasing appeal of sports utility vehicles (SUVs) and spurred development of other multifunction vehicles.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. This matrix (Figure 6.12) explores two key dimensions: Fuel Prices and Societal Values:

Fuel Prices. Fuel Prices are a key driver of economic activity in almost all industries, particularly transportation. They range from low to high.

Societal Values. Societal Values provide a complex and nuanced measure of social conditions that might drive car-buying patterns. Traditional Values describe a conservative society in which religious, social, and personal values are relatively stable. In this vision, nuclear families would become stronger, gender roles would be well defined, and traditional practices in all fields would remain dominant. Inner-Directed Values describe a society that places greater emphasis on self-fulfillment and less fidelity to social norms. In this vision, people would be more likely to tackle anything new, from exotic religious practices and extreme sports to experimental social practices and nontraditional brands. Values, combined with fuel prices, spawned four plausible yet vastly different scenarios.

The Four Quadrants. Values, combined with Fuel Prices, spawned four plausible yet vastly different scenarios:

Upper left: Engineer's Challenge. Under this scenario, North America falls prey to the kinds of continuing high fuel prices that were first experienced during oil embargos in the 1970s (returning again in 2003). The challenge for auto companies becomes how to build innovative, fuel-efficient cars while appealing to a customer base whose taste and values reflect an earlier period when car design was driven by style and power, not efficiency.

Lower left: Long Live Detroit. In this scenario, the domestic car industry in North America would benefit from the combination of permanently low gas prices and a customer base that stuck close to traditional brands. Firms would build the types of cars (gas-guzzling muscle cars) that were popular in the 1960s. While muscle cars continue to come and go, this clearly was not the dominant scenario.

Lower right: Foreign Competition. A lack of traditional brand loyalty, combined with low fuel prices, would enable Japanese and German firms to capture an ever-increasing share of the U.S. market. Sportier cars, light trucks, and vans would proliferate as tastes splintered and markets fragmented.

Upper right: Green Highways. This is the eco-dream quadrant. High fuel prices make the return of inefficient automobiles unlikely. Inner-directed values drive customers to focus on the more sober aspects of car ownership, such as pollution control, fuel efficiency, and the effect of automobiles on the environment. As a result, automakers vie with one another to produce more eco-friendly vehicles.

At the time this set of scenarios was being developed, the two upper quadrants seemed quite likely. The world had become accustomed to higher oil prices in the 1970s, and there was little expectation that we would have sustained energy deflation throughout the 1990s, but that is what happened. Gas prices in real terms were far lower in the 1990s than in the two previous decades. At the same time, people in North America moved right on the horizontal axis, becoming more inner directed overall. The lower right quadrant turned out to model the automotive future more accurately than the other three. By the end of the century, light trucks, vans, and SUVs dominated car sales, and foreign firms had racked up impressive gains in market share.

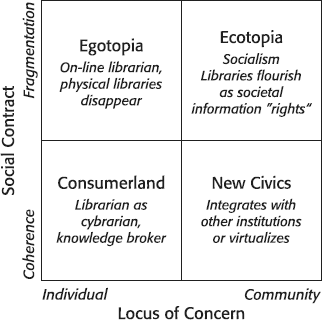

Example 2: Librarian Scenario

The basic structure of the Librarian Scenario matrix was developed by Lawrence Wilkinson of the Global Business Network.[52] It was adapted by Tom Wilson of the University of Sheffield to explore the future of library services and its impact on the job prospects of librarians.[53]

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The matrix explores two key dimensions: Social Contract and Locus of Concern (Figure 6.13):

Social Contract. The degree to which society is likely to share common values (Coherence) or to fragment into conflict among interest groups (Fragmentation) defines the extremes of the Social Contract. In fragmented societies, central authorities exercise control over the behavior of individuals. In Coherence scenarios, shared values makes such control unnecessary.

Locus of Concern. The Locus of Concern represents the long-standing struggle between the Individual and Community. It asks, "Will the key locus of concern for citizens be the well-being of the community or themselves?"

The Four Quadrants. The four quadrants illustrate the possibilities:

Upper left: Egotopia. In Egotopia, Community is disintegrating. Individuals are connected by the Internet and do much of their work there. Since Individuals have less stake in the community, social infrastructures decline. Under such a scenario, physical libraries are likely to disappear, replaced by on-line librarians who provide open market services electronically.

Lower left: Consumerland. A strong social contract supports the need for shared physical and on-line public libraries. But the librarian focuses on serving individuals, not groups. In this vision, the librarian is a "cybrarian," brokering knowledge to the members of society.

Lower right: New Civics. The New Civics envisions a strong Social Contract combined with strong Communities. In this future, the library remains an important community component that might integrate with other institutions in order to perform its mission better.

Upper right: Ecotopia. In Ecotopia, libraries are a right, not a luxury. This is envisioned as a more socially responsible future in which communitarian values prevail. Although social cohesion is low, support for institutions of business and government remains high. Corporations focus more on meeting social goals, and citizens exercise power to clean the environment and fund needed services.

Under all four scenarios, physical libraries were considered likely to decline and on-line services would grow. Also, there would be a demand for librarian services under all four scenarios. In some, such as New Civics and Ecotopia, this appears to be greater due to the commitment to maintaining physical libraries, but overall, the scenarios demonstrated a continuing demand for fee-based and public library services.

Method. Scenario planning can be an intensive process, involving many people and lasting several months. In his book The Long View, Peter Schwartz provides an overview of the scenario planning process that is adapted here:[54]

Step 1: Focus. Identify the focal issue of your decision. Scenario development works better by looking inside out, examining the kinds of major decisions you'll be grappling with this year and in the future. Identify some key decisions that have to be made and will have big repercussions on the firm, such as, "Should we build the new facility?" or "Is it wise for us to enter the European market?"

Step 2: Examine key environmental forces. What are the local factors—such as information about suppliers, customers, and competitors—that influence the success or failure of decisions chosen in step 1? What will be the key determinant of success for the decision in step 1?

Step 3: Identify driving forces. Examine the economic, social, political, demographic, and technical driving forces that are external to the firm. These range from high certainty (demographics) to low certainty (political upheavals) forces. Typically, additional research is required to support your conclusions at this step.

Step 4: Prioritize issues. Take your macro (step 3) and micro (step 2) lists, and rank them by importance and uncertainty. If working in groups, suggest giving each person three votes, and use the votes to establish priorities.

Step 5: Build the scenario logic. The ranked factors provide the raw material for creating the axes of your 2 × 2 matrix. Work as a team on the meaning of the two axes, and pay special attention to factors that may be combined or integrated. Language is critical at this stage. Global Business network consultant Nicole Boyer says, "The planning team must own the language describing the axes and each quadrant. The story has to feel right for it to make an impact on an organization."

Step 6: Flesh out the scenarios. Describe in some detail (one to four pages) what the world would look like if any of the four scenarios came to pass. What would be the impact on the use of your product or services, commodity prices, shopping habits, government policies, or other areas of life that would affect your business? Look again at the key drivers in steps 1 and 2, and visualize how they might play out under each scenario.

Step 7: Consider strategic implications. Scenarios enable you to test strategies for risk. Boyer asks, "Are your strategies robust in all four quadrants? Do you die? Do you thrive? You may have strategies that are moderately risky in all scenarios, or you may have a big bet that is very risky in most of the scenarios. If all the scenarios are equally likely, would you bet your company on only one of them?"

Step 8: Create measures and signposts. Once a solid set of scenarios is developed, ask, "What are the key measures that tell us if the future is unfolding according to one of the scenarios?" Look for simple indicators that might provide useful information. For example, if one of your scenarios is increasing community fragmentation, how would you measure that? Household formation? Parent-Teacher Association attendance? Divorce rates? These indicators provide an early warning system for future strategic choices.

Ringland, G. Scenarios in Business. New York: Wiley, 2002.

Schwartz, P. The Art of the Long View. New York: Doubleday, 1992.

van der Heijden, K., and others. The Sixth Sense: Accelerating Organizational Learning with Scenarios. New York: Wiley, 2002.

Wilkinson, L. "The Future of the Future." Wired (special edition), 1995, pp. 77–81.

[http://www.wired.com/wired/scenarios/build.html].

Wilson, T. "The Role of the Librarian in the Twenty-First Century." Keynote address for the Library Association Northern Branch Conference, Longhirst, Northumberland,

Nov. 17, 1995. [http://www.shef.ac.uk/~is/wilson/publications/21stcent.html].

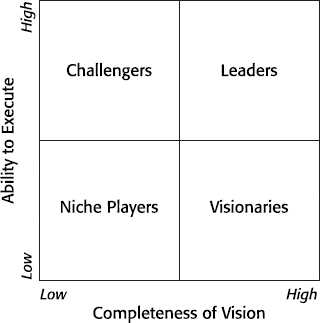

Leadership is the capacity to translate vision into reality.

Major information technology buying decisions are among the most expensive and fateful that executives make. They must choose suppliers that understand their business, stand behind the product, and can provide needed services. The investments are typically long term, so they must choose a vendor that will be around in the future—one with the vision and foresight to survive in the cutthroat technology marketplace.

Gartner Inc., founded in 1979 in Stamford, Connecticut, is the leading research firm providing insight and advice to corporations on technology markets and products. Gartner associates serve as independent counsel on strategic business issues and often are called before the U.S. Congress to discuss the technology issues driving the economy.

The Gartner Magic Quadrant (Figure 6.14) describes the relative positioning and future prospects of firms in technology hardware, software, and services. Producers take Gartner's ratings seriously and devote significant marketing resources to building the case that they are material for the upper right—the Leaders quadrant.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Magic Quadrant measures firms' offerings by contrasting two business values: Ability to Execute and Completeness of Vision. Long-term success in information technology requires both. Completeness of Vision is most important when a product category is new and customer needs are evolving rapidly. Ability to Execute becomes more important over the longer term as companies require support and customized solutions to meet specific needs.

Ability to Execute. Ability to Execute reflects the discipline and resources—human, financial, intellectual—needed to get the job done. In addition to core competencies, firms rated high on Execution display financial strength and the right strategic alliances along the value chain.

Completeness of Vision. Completeness of Vision focuses on creativity and inventiveness. It measures a firm's ability to lead and influence the direction of technology development and implementation practices in their market.

The Four Quadrants. Combinations of the two dimensions define four possible competitive positions:

Upper left: Challengers. These companies execute well and often dominate large segments of the market. However, they are not fully in step with emerging market directions or capable of setting the industry agenda.

Lower left: Niche Players. These are often smaller competitors with credible technology or firms focused on smaller market segments. Firms in this quadrant are judged not to excel at either innovation or performance.

Lower right: Visionaries. Visionaries understand where the market is going but do not have all the capabilities necessary to execute the vision. Companies in this quadrant are notable for their breakthrough ideas but are challenged to develop the broad competencies needed to support and sustain customers.

Upper right: Leaders. Leaders execute well today and are positioned for the future. These are companies with excellent customer service, dynamic solutions, and strong value delivery. Gartner recognizes firms that can adhere to a well-articulated strategic plan, align their vision with industry trends, and are flexible in reacting to market forces.

Example: Supply Chain Software. The matrix is a regular feature of the Gartner Group's research reports on software and hardware technology. Each Magic report includes market analysis, vendor inclusion criteria, and comments from Gartner's army of analysts. Page 124 contains two examples of what a completed matrix looks like. (While names have been deleted, each dot represents a real company evaluation.) The quadrant in Figure 6.15 compares supply chain management (SCM) software vendors. SCM software is typically bought in a suite that may include applications for demand planning, manufacturing planning and scheduling, distribution transportation planning, and other processes. A firm needs to meet stiff criteria, including a global presence and broad product offering, to be considered for inclusion in the Magic Quadrant. As a result, new entrants are often excluded. In this example, only two firms are ranked above the midpoint on the Ability to Execute dimension. Since Gartner maps are issued frequently, each one is a current snapshot, and it is not uncommon for companies to change their position on the map over time.

In new markets, few products or firms meet all the criteria for leadership. The Portal Software example (Figure 6.16) is a map of the emerging company portal software industry in 2000. At that time, the market was still quite small, and few products or companies had proved they could adequately meet customer needs or implement and service their products. Gartner rightly identified that no companies ranked high on Ability to Execute.

Context. The Gartner Magic Quadrant offers a relatively simple and powerful way to model industry competitors. It is well suited to corporate strategic planning exercises in any field where technology changes increase the risks of vendor selection.

Method. Follow these steps to conduct a Magic Quadrant analysis:

Step 1: Define the problem. In a sentence, articulate the business issue you intend to confront.

Step 2: Create a matrix. Focus the dimensions of the axes with a list of key issues relating to the specific problem at hand. For Completeness of Vision, consider the number of new products, research and development, technology, and standards. For Ability to Execute, consider financial viability, track record, management quality, investor relations, impact of government legislation, and production systems. Then define your own list of additional key issues for each axis.

Step 3: Assess. Place all relevant industry players on the matrix according to your first instinct. Then with an associate, debate and review each company until you are satisfied that the placement is fair and accurate. The more people who validate the matrix, the more reliable it will be for decision making.

Step 4: Follow up. Update the matrix following major announcements by players and new entrants. Over time, you will gain a better understanding of industry trends and organizational strategies.

Unfortunately, not all business is good business.

Not all customer accounts are worth pursuing or maintaining. Companies understandably have a difficult time rejecting business, but this is sometimes precisely what they should do. This applies to existing accounts as well as those in the sales pipeline. The Portfolio Analysis matrix provides a useful structure and set of criteria for assessing the relative value of customers (Figure 6.17).

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Portfolio Analysis matrix explores two key dimensions: Business Quality and Mutual Value:

Business Quality. Business Quality is considered Excellent if the relationship is profitable and growing and the client is satisfied. It is Poor if engagements are unprofitable, missing milestones, draining resources, or the client is dissatisfied.

Mutual Value. Mutual Value is a measure of the interdependence between service provider and client. Mutual Value is Symbiotic when the client and service provider are able to produce new, positive results that they could not have achieved separately. For example, Motorola recently outsourced its human resource department to Affiliated Computer Services (ACS). Gaining critical mass and a marquee client enabled ACS to bring its business process outsourcing (BPO) offering to market faster and to add functionality, increasing its competitiveness. Motorola gained access to best-in-class human resource and process management practices from ACS and was able to remain focused on its core competencies. It also retained a royalty on other BPO engagements that ACS sells. Beneficial Mutual Value to the service provider could also mean expanding into new vertical industries, establishing recurring revenue streams and creating an offering that can be replicated. Mutual Value is considered to be Nonexistent when service is rendered primarily as a low-cost alternative.

The Four Quadrants. Careful consideration of Business Quality and Mutual Value produces four strategic options:

Upper left: Maintain. Work of this nature is worth doing for the money but contributes little to long-term strategic development. Cash cows tend to be in this quadrant. Some of these businesses will eventually need to be cannibalized; however, in the interim, they help fund new growth initiatives.

Lower left: Exit. This type of client relationship is unsupportable and should be renegotiated or stopped as soon as legally and morally possible.

Lower right: Adjust or Limit. These assignments are strategically well aligned, but they are not profitable and may not be generating additional work. An example is the development of emerging technologies where investment is required to be competitive. These engagements need to be closely monitored. Some activities in this category can be promoted and developed into prime work, while others will need to be cut.

Upper right: Grow. This is the best quadrant for business to fall into. It is profitable, growing, and strategically well matched, representing a virtuous cycle of learning, growth, and profitability. Ideally, relationships started in the other boxes can be directed here.

Method. Use the Portfolio Analysis matrix to evaluate and optimize client relationships:

Step 1: Diagnose. Assess all current and prospective customers, applying the two dimensions of the Portfolio Analysis matrix. Place each customer in the appropriate quadrant of the matrix. Use large and small circles to denote the size of client engagements. Color coding the circles or markers can also be used to quickly identify specific types of engagements.

Step 2: Plan. Create plans for each customer. Some merit additional effort and attention, while other relationships may need to be terminated.

Step 3: Execute. Apply plans and monitor for changes in status.

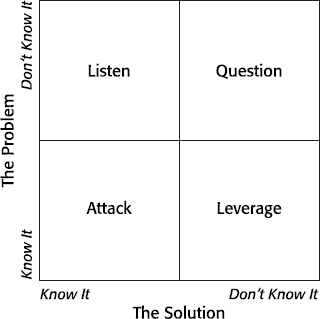

Wait for the future to happen, and you will have no future.

Watts Wacker is perfectly at home in the future. As a former futurist at SRI and now with his own firm, First Matter, he advises top corporations on how to nurture long-range planning capabilities. In The Visionary Handbook, he coaches firms to set up an internal futures council to continually assess issues related to their future development. The council creates a future vision for the company and monitors evolving sets of problems and solutions that may have significant impact on the company in the future.

The Problems and Solutions matrix (Figure 6.18) asks, "How do we apply company resources to the problems and solutions in our future vision?"

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Problem and Solution matrix explores two key dimensions: Problems and Solutions:

The Problem. Problems range from today's known problems to emerging issues that a future vision reveals. For example, demographic changes can signal future problems that will require attention.

The Solution. Solutions may be known and obvious today or unknown and yet to be discovered. New technologies (such as wireless) or new paradigms (such as mass customization) frequently start out as solutions to unknown problems.

The Four Quadrants. Different action is needed depending on whether Problems and Solutions are known. The four basic options are described as follows:

Upper left: Listen. If the futures council is paying attention, it will identify ideas that solve problems that are not yet evident. These solutions challenge the firm to make sense of weak signals from the marketplace and recognize possible future trends. Seek input from thought leaders and mentors whose perceptive contributions can help you re-vision the present and future.

Lower left: Attack. Sometimes the situation is clear and compelling. You know what's wrong and what you need to do, so take action.

Lower right: Leverage. The problem is known, but you don't have a solution. In this case, leveraging the knowledge and efforts of partners and friends is suggested to lead more quickly to a solution.

Upper right: Question. Wacker calls this the fool's box, referring to medieval fools or jesters. Organizations must actively nurture renegades who question and present bold ideas if they are to get beyond the limits of today's problems and solutions. In this manner, one remains open to transcendent solutions to tomorrow's challenges.

Method. The method has three steps:

Step 1: Form. Establish a futures council within the firm composed of people at different levels.

Step 2: Assign. Charge the futures council with creating a vision of the future. Include in the vision a list of questions (problems) and answers (solutions) that could have an impact on reaching the company's future vision.

Step 3: Follow up. On a continuing basis, test the futures council's list of problems and solutions against the matrix, and take appropriate action.

Opportunities are like buses. There is always another one coming.

SWOT is the acronym for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. In a traditional SWOT analysis, these four categories are investigated independently and fed into the planning process. In dialectical SWOT, we treat Strengths and Weaknesses as internal factors and Opportunities and Threats as external. Traditional SWOT analysis generates a powerful and reasonably comprehensive strategic snapshot. The unique value in this approach comes from juxtaposing information from these two categories, as shown in Figure 6.19. Each quadrant of the matrix represents a unique combination of Internal and External conditions, and each produces a specific recommendation.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The SWOT matrix explores two key dimensions: External Environment and Internal Environment:

External Environment. Organizational success depends on sensing and responding to shifting conditions in the business environment. At the most basic level, these represent Opportunities and Threats.

Internal Environment. The ability to compete effectively depends on the resources and knowledge available to the organization. We draw on our Strengths and guard against possible exposure created by our Weaknesses.

The Four Quadrants Dialectical SWOT defines four zones of risk and reward, each demanding a different response. The key to success often lies in being proactive:

Upper left: Confront. Threat is matched with organizational strength. Businesses face these conditions all the time—new competitors, legislative changes, commoditization of a core offering, and many others. Mobilize to limit and control the looming danger.

Lower left: Exploit. Opportunity is matched with strength. This is a business's growing edge, where it can capitalize on areas of strategic advantage. The one caution here is to be careful not to ignore other demands. Vital and scarce corporate resources are too easily drawn to exciting and rewarding growth-oriented projects, which can deplete the organization's ability to deal effectively with more mundane and defensive challenges.

Lower right: Search. Opportunity is matched with weakness. This quadrant represents a conundrum. Opportunities exist that the organization can recognize but is not equipped to tackle. The gap may be financial, scale, location, or any of a number of other factors. Creative options are needed. If you don't act on the opportunity, perhaps a competitor will, with potentially disastrous consequences.

Upper right: Avoid or Prepare. Threat is matched with Weakness. Some threats are avoidable, and others are not. Confronting competitive Threats with Weakness is not only dangerous but also resource draining. When possible, it is best to avoid such situations. Consider the company about to enter a price war with a much larger and better-financed adversary. Sometimes, however, the threat cannot be sidestepped and must be addressed, whatever the cost.

Method. Follow these steps to conduct a dialectical SWOT analysis:

Step 1: Generate lists of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Be sure the people involved in completing this task have the necessary knowledge and independence to report in an honest (not fearful or protective) way.

Step 2: Assess the interactive effect of the internal (Strengths and Weaknesses) and external (Opportunities and Threats) observations. Place the conclusions onto the dialectical SWOT matrix.

Don't plan to play the high[er] stakes, winner-take-all battle to become the standard unless you can be aggressive in timing, in pricing, and in exploiting relationships with complementary products.

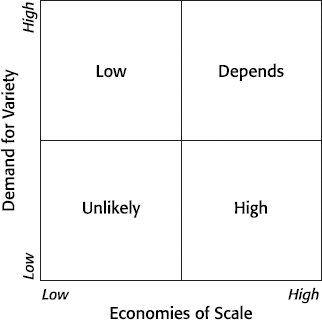

It is not unusual for technology markets to be dominated by a single technology standard, and sometimes by a single large firm. The Market Tipping matrix (Figure 6.20), introduced by Carl Shapiro and Hal R. Varian in Information Rules, examines whether a developing technology market will tip to a single dominant player. It is risky to compete in "tippy" markets, since losers can end up with zero market share.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Market Tipping matrix explores two key dimensions: Demand for Variety and Economies of Scale:

Demand for Variety. Demand for Variety ranges from Low, in which one standard prevails (such as the QWERTY keyboard), to High, in which the market supports competing standards (as in data storage technologies). Variety should not be confused with implementing a standard design in a broad fashion. DVD players are implemented in different styles, but to users, compatibility with the existing interfaces and formats is more important than style. When customer demand for variety is low, the dominant player can be dislodged only by vastly superior technology or favorable economics, such as low or no switching costs.

Economies of Scale. Economies of Scale refer to cost advantage as a result of size or volume. They can be demand side or supply side in nature and range from Low to High.

The Four Quadrants. The matrix describes four degrees of likelihood that a market will "tip" to a single supplier: