Good to Great Matrix of Creative Discipline

Employee Motivation

Alliance Drivers

Team Types

Leadership and Culture Frameworks

Situational Leadership

The Four Power Players in Knowledge Organizations

T-Group Leadership

Learning and Change Frameworks

SECI

Human Capital

Differentiation and Integration

Means and Ends

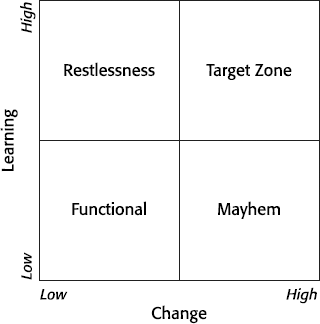

The Change Grid

Learning and Change

Similarities and Differences

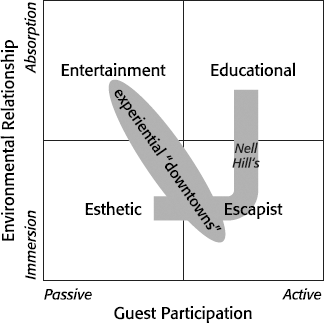

The Four Realms of Experience

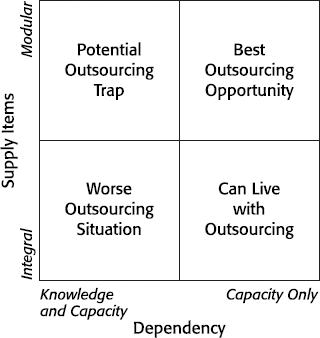

Make versus Buy

Four Square Model

Product and Supply Chain Architecture

Telematics Framework

The Virtue Matrix

The prime organizational challenge has shifted from efficiency to agility (Figure 7.1). It's not that efficient operations are no longer important; they simply are not enough, and businesses are building structures and processes that ensure rapid sense-and-response ability.

To maintain pace with dynamic external environments, firms are flattening their vertical structures, empowering front-line staff, and forming external partnerships that provide access to necessary but noncore capabilities. With each move in this direction, some formal power is forfeited. Control is being replaced with knowledge as firms tap the resources of three critical constituencies: employees, strategic partners, and customers. Business leadership today consists of directing and aligning the efforts, creativity, and goodwill of numerous disparate parties without the luxury of formal authority to set goals and enforce compliance.

Note

The Archetypal Organizational Dilemma

Core Question: How can our organization be more effective?

Key Issues: Design and management of structure, jobs, and processes

The modern business organization was born during the industrial revolution in the processing and manufacturing industries of England, Europe, and the United States. Masses of people migrated from rural farming communities to work in the new factories, using processes that were tightly defined and left little room for creativity or initiative.

Built to leverage the power of machine technology, early organizational models were mechanistic and rational, the primary goal being to maintain efficient and reliable operations. It was all about the machine and the assembly line, finding economies of scale through technical design and efficient management.

The human relations school of organizational management grew in reaction to the impersonal and often exploitative aspects of the scientific approach. Supported by parallel developments in individual and social psychology, proponents focused on human potential, feelings, and job designs that led to work that was fulfilling as well as efficient. Work innovations like GE's Hawthorne experiment, MacGregor's Theory X and Y, and Frederick Herzberg's Job Enrichment demonstrated that happy, engaged workers were more productive: treat someone like a gear, and the person will think like one; treat her with respect, and she will seize the opportunity to perform responsibly and professionally.

In dialectical terms, a tension had set up between the two philosophies, which eventually gave rise to integrative approaches drawing on the best of both schools of thought. Socio-technical systems, like the original form of the corporation, first appeared in England, in the coal mines shortly after World War II. A blend of the two approaches, it captured the interest of two types of companies: those where social problems engendered by the technical-rational approach were creating motivational or labor problems, and progressive companies with visionary and adventurous leaders interested in establishing ideal, high-performance working conditions. Two well-known examples were GM's Saturn plants and Shell's redesign of its chemical processing facilities.

As in the case of strategy, traditional approaches to achieving organizational effectiveness are being challenged by the forces of complexity (faster, more dynamic contexts make agility a necessary core competency), technology (digital technologies enable better, cheaper work production, and communications make technology a core competency), and globalization (redefinition of the location of workers and available markets sets wider boundaries for firms).

The result of these factors is a reconceptualization of the firm, work, and day-to-day operating challenges. The contemporary self-organizing, complexity-managing, risk-mitigating, constantly learning business organization is different. Prime skills now include sensing the environment; recognizing and resolving dilemmas; creating and sharing knowledge; retaining, motivating, and training talented employees; and partnering with suppliers and customers.

This chapter explores a rich assortment of organizational frameworks in the following four categories:

Structure: The way we design jobs and business processes either helps or hinders effectiveness. These frameworks assist us to define and structure work in ways that improve performance.

Leadership and culture: Organizations are communities bound by shared values and rules. Some of these are formal; many are implicit. Leadership is provided by a variety of individuals, some drawing on formal authority and others calling on their ability to influence through expertise, seniority, or relationships.

Learning and change: Managing change may well be the new norm, however it remains a challenging and often painful process. Learning is viewed as a key enabler of healthy and successful change processes.

Process: Systems can be greatly improved by applying a process design orientation. We do this by treating each process step and transaction as modular components that may or may not be ideal or even necessary. Working with prescribed tools and principles, existing sequences can be upgraded and whole new steps created.

How do we organize work and people?

Organization design is meant to facilitate productivity through engineering individual and collaborative efforts. It would be hard enough to do this right if we all agreed on goals and design principles and if technologies and conditions didn't constantly change.

We sometimes overlook structural problems because structure is difficult to design and painful to change. At other times, we mistakenly turn to structure to fix interpersonal, process, or competitive problems. The frameworks in this chapter offer a variety of ways to approach the design of work and organizations sensitively, carefully, and creatively.

The question of "Why greatness" is almost a nonsense question. If you're engaged in work that you love and care about, for whatever reason, then the question needs no answer.

The Good to Great matrix (Figure 7.2) comes from the book of the same name by Jim Collins of Stanford University. Collins examined the financial performance of 1,435 Fortune 500 companies over three decades to find those capable of lifting their financial performance above the market and above the averages for their industry. His intent was to identify the special qualities that enabled organizations to ascend from sustained good performance to sustained great performance.

Collins's methodology included exhaustive secondary research, long-term financial analysis, and extensive interviews with company executives. One of his key findings was that good to great companies were successful on two cultural dimensions: Discipline (the ability to set goals and enforce accountability) and Entrepreneurialism (a culture of freedom, innovation, and risk taking). The tension between creativity and innovation, on the one hand, and discipline and financial control, on the other, is well known to CEOs. Synthesizing the two forces over the long term is surprisingly rare: only 11 of 1,435 companies were able to make it through Collins's research filter and qualify as good to great.

Most successful start-ups do not go on to become great companies. As a business becomes successful, it grows in complexity. In time, the characteristic easygoing informality of the start-up becomes a liability rather than an asset. Many firms flounder when it becomes necessary to impose tighter discipline on the organization. As professional managers replace the entrepreneurs who started the firm, the culture undergoes changes. If left unchecked, it becomes increasingly hierarchical, internally focused, and ultimately a place where creative innovators no longer want to be.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Good to Great matrix explores two key dimensions: Culture of Discipline and Entrepreneurial Ethic:

Culture of Discipline. Firms with a Culture of Discipline excel at setting and achieving business goals. They institute mechanisms for planning, measuring, and changing course as needed, and have trained managers to use them.

Entrepreneurial Ethic. Entrepreneurial Ethic means that a firm has maintained a start-up kind of enthusiasm for customers and products. These organizations encourage innovative thinking and reward action over analysis.

The Four Quadrants. Firms may start out as Entrepreneurial ventures; however, Discipline is eventually needed to sustain operational effectiveness. Collins describes four outcomes of the trade-offs between these two factors:

Upper left: Hierarchical Organization. The hierarchical firm is effective at setting goals and managing to meet objectives. However, it has become focused on the wrong attribute at the core of the organization. In the Good to Great view of the world, discipline is a means to enabling more innovation and creativity, not an end in itself. In Hierarchical Organizations, leaders overvalue order and control, and drive innovative rule breakers out of the firm.

Lower left: Bureaucratic Organization. In the Bureaucratic Organization, goals are set but not met. Accountability is diffuse. Failure may not be rewarded, but it is tolerated. Many firms develop this type of culture at some point in their life cycle. For a recent example, consider the national telephone companies prior to privatization.

Lower right: Start-Up Organization. In the start-up phase, firms depend almost solely on innovation for success. Entrepreneurial activity is rewarded, and risk takers who succeed become stars. The few start-ups that become great firms build on their innovations to create methods for repeating that success and nurturing freedom in the firm.

Upper right: Greatness Organization. Great organizations build a culture of freedom and innovation, and then introduce enough discipline to ensure cooperation without creating unnecessary bureaucracy. Their cultures are inclusive and forgiving—employees have no fear of bringing bad, but realistic news to executives—and open to innovation.

Example: Kroger and A&P. In 1950, A&P was the world's largest retailer, and Kroger was a midsized competitor.[84] Around 1970, Kroger research determined that market demand was shifting. Customers wanted superstores: well-lit, clean outlets with lots of services and much wider selection than traditional grocery stores. Through the 1970s, Kroger remade the company in response to changing customer demand (Figure 7.3).

Up to that point, both A&P and Kroger tended to have older, smaller stores in slow-growing parts of the country. Kroger rebuilt itself from the ground up, store by store, going so far as to pull out of regions where its new superstores were unlikely to succeed.

In contrast, A&P stayed mired in the past. The CEO conducted himself as if he were the caretaker representative of the founders, often wondering, "What would Mr. Hartford [the founder of A&P] do?" in response to strategic questions. Attempts to change the existing supermarket model were regularly shot down, and promising new store experiments were nixed. It is no wonder that customers increasingly overlooked its stores. As sales fell, the company engaged in ruinous price wars, which sucked up profits that could have been used to improve stores, as competitors were doing. Over three decades, the once-great Atlantic & Pacific Company fell apart, as Kroger's stock outperformed it eighty times over. In 1999, Kroger became the nation's largest grocery chain.

Context. The Good to Great matrix invites sobering comparisons between a firm and its competitors on two vital dimensions. And, it poses a question: Is your firm settling for merely being good when it could be great?

Method. Follow the steps below to conduct a high-level analysis of your organization's adequacy regarding discipline and entrepreneurialism:

Step 1: Assess the culture of discipline. Rank yourself and three competitors (from highest to lowest) in terms of discipline. How consistent are the firms at hitting their financial performance targets? Are employees focused on internal politics or on listening to the market and customers? Are processes in place to manage and track performance properly?

Step 2: Assess entrepreneurialism. Rank yourself and competitors in terms of entrepreneurialism. Ask the following questions: Are new ideas encouraged? Is failure tolerated within the culture as long as people take responsibility for their actions? Is the organization making strategic moves that indicate a keen sense of how the industry is changing and evolving? Is it an innovation leader within its field?

Step 3: Determine your current state. Using what you have learned, place your firm and competitors on the matrix.

Step 4: Create an improvement plan. Consider implications of the current state, and identify areas needing improvement.

If only a small percentage of the time and money that is now devoted to hygiene, however, were given to job enrichment efforts, the return in human satisfaction and economic gain would be one of the largest dividends that industry and society have reaped through their efforts at better personnel management.

If we remove the dissatisfaction from a job, we do not necessarily end up with a motivated employee.[86] Job satisfaction and dissatisfaction are not opposites; rather, they describe two different, and critical, aspects of work. Fulfilling, motivating work derives from the design of the work itself—Motivators—while dissatisfaction results from poor work conditions—Hygiene (Figure 7.4). Better lighting, for example, removes a problem but does not make a job more interesting or meaningful. This was the insight that Frederick Herzberg introduced in his 1966 book, Work and Nature of Man, and classic 1968 Harvard Business Review article, "One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?" Too often, efforts to motivate concentrate on Hygiene factors. Applying Herzberg's framework gave birth to the job enrichment movement of the 1970s and continues to influence current approaches to job design and high performance.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Motivating Employees matrix explores two key dimensions: Motivators and Hygiene:

Motivators. These are factors that are intrinsic to the job, such as achievement, recognition, the work itself, responsibility, growth, and advancement.

Hygiene. These are factors that are extrinsic to the job, such as company policy, administration, supervision, interpersonal relationships, working conditions, status, salary, and security.

The Four Quadrants. The effective design of work recognizes the need to address both Motivator and Hygiene factors. Inattention to either one places a drag on overall job satisfaction and organizational performance effectiveness:

Upper left: Fulfilling But Frustrating. The work itself is interesting and worth doing; however, environmental conditions get in the way. People would do great work if only the barriers were removed.

Lower left: Total Job Dissatisfaction. Both the job and working conditions are poor. Performance effectiveness is low and motivation is highly unlikely without serious efforts at improvement.

Lower right: Comfortable But Unfulfilling. Working conditions are excellent, but the work lacks sufficient challenge or opportunity to achieve something meaningful. Employees could do great work if they wanted to, but they won't because they are not motivated.

Upper right: Total Job Satisfaction. The ideal situation exists when both Hygiene and Motivator factors are addressed. Employees feel good about the working environment, there are no unnecessary barriers to performance, and the work is highly motivating.

Method. Herzberg proposes a ten-step process for applying these ideas for job enrichment. The core of the approach is contained in three steps:

Step 1: Identify the target job.

Step 2: Conduct a Hygiene audit. Ask, "What is frustrating about this job?" Address key issues.

Step 3: Conduct a Motivator brainstorm session. Ask, "What would make the job a richer and more meaningful experience?" Consider the core Motivator factors: achievement, recognition, the work itself, responsibility, and growth or advancement.

Herzberg, F. Work and Nature of Man. New York: World Publishing Company, 1966.

Herzberg, F. "One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?" Harvard Business Review, Sept. Oct. 1987, pp. 53–62.

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., and Snyderman, B. B. The Motivation to Work. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1993.

The companies that are most successful with alliances have learned the importance of embedding the capability to create alliances in the corporate structure.

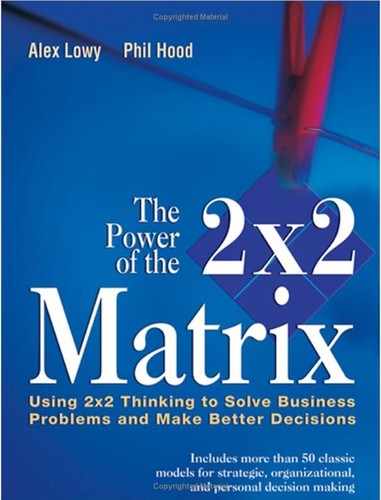

The Alliance Drivers matrix (Figure 7.5) is based on long-term research into more than five hundred major firms and six thousand strategic alliances. In their book Smart Alliances, Harbison and Pekar document how alliances have grown in importance as drivers of corporate revenue growth and as a source of strategic advantage. (They defined strategic alliances as partnerships among relatively equal firms that involve long-term commitments with shared resources, funding or equity.)

The research demonstrates that two factors, Globalization pressures and Capability Gaps, have played a major role in determining the need for corporate alliances in recent years. The degree to which these drivers are present varies greatly by industry. In some sectors, firms must establish a worldwide presence if they are to stay competitive. In others, the need to continually update and acquire new capabilities drives alliances. Although there is little direct tension between Globalization and Capability Gaps, the dialectical conflict is implicit and important. Alliances are inherently risky and involve complex issues of dependency and control.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Alliance Drivers matrix explores two key dimensions: Globalization and Capability Gap:

Globalization. Globalization refers to the pressure to establish an international presence and succeed in foreign markets. Industries with high levels of global consolidation (autos, telecommunications) fit this definition.

Capability Gap. Capability gaps arise when companies lack the skills, knowledge, or scale to meet fast-changing market demands. Increasingly, firms are turning to partners to fill those gaps.

The Four Quadrants. The degree to which Globalization and Capability Gap drive the need for an alliance defines four strategic approaches:

Upper left: Channel Access. Some foreign markets require a large retail and wholesale distribution network in order to compete effectively. In such cases, firms need to seek local partners with a significant footprint in their home territory.

Lower left: Pooled Resources. In industries such as steel, paper, and utilities, products have high weight-to-value ratio, creating transportation difficulties or other barriers that insulate firms against foreign competition. Companies in these businesses should ally in order to reduce risk and exploit economies of scale.

Lower right: Critical Mass. In industries such as health care and entertainment, firms find themselves facing new market demands as industry boundaries blur. They should consider partnering with firms outside their traditional business domain to build a critical mass of skills and audience. Such was the case with Microsoft and NBC, which coinvested to create MSNBC.

Upper right: Global Leadership. Firms in industries characterized by rapid technological innovation, like computers, telecom, and electronics, should seek partners that can fill in capability gaps that provide an immediate technological edge. The Sony-Ericsson partnership to produce mobile phones is one such alliance.

Method. Harbison and Pekar include a robust alliance planning method and a detailed matrix for analyzing alliance needs and opportunities. We suggest the following exercise as a way to initiate a review process:

Step 1: Scan. Make a list of recent or planned strategic alliances at your firm.

Step 2: Assess. List the technologies, capabilities, access to markets, and other assets you hope to acquire through strategic alliances. Check whether the drivers in Table 7.1 are present.

Step 3: Diagnose. Using the information you've gathered, plot your strategic alliances on the matrix. Consider the implications of the matrix. Are alliances addressing the globalization forces and capability gaps you face?

Harbison, J. R., and Pekar, P. Jr. Smart Alliances. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1998.

Teams should be set up to elicit not the compliance of the workforce, but its commitment.

Collaboration is increasingly important in the knowledge era. Team effectiveness is a prime forum for collaboration and thus an important driver of high performance. Yet we tend to approach the vast assortment of work teams in the same way, rather than recognizing structural and contextual differences. Kimball Fisher has written extensively on the subject of teams and has helped many organizations to improve their team practices. The effort begins with getting clear about business and organizational requirements and the type of teams that are needed. Teams differ in their Duration and Scope. Each of the four team types resulting from this model has unique performance properties and development needs (Figure 7.6).

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Team Types matrix explores two key dimensions: Duration and Scope:

Duration. Teams are created to tackle a short-term need, or they are ongoing.

Scope. Teams perform within a single, defined area, or they are tasked with outputs that touch multiple operations.

The Four Quadrants. Team structure needs to align with task requirements and organizational values:

Upper left: Natural Work Teams. The most common types of teams are those formed around business functions and processes in organization, like the radiology department in a hospital or the R&D group in a midsized software company. These teams have ongoing responsibilities to deliver defined outputs.

Lower left: Small Project Teams. Temporary teams are created within business units to solve a specific problem or assist in the design of new methods. Examples include resolving equipment problems and scheduling vacations.

Lower right: Special-Purpose Teams. When a short-term task cuts across a larger portion of the organization, an interfunctional team is required. Participants bring technical knowledge as well as the ability to represent the interests of their colleagues.

Upper right: Cross-Functional Teams. Communication and coordination across organizational boundaries are often achieved with cross-functional teams. These typically meet on a regular basis to review systemwide issues and provide representative input. Examples are safety, training, and quality improvement.

Method. Team form should be guided by task function and organizational culture:

Step 1: Diagnose. Determine if a team is required by considering such issues as interdependence, need for communication, and ability to influence.

Step 2: Envision. If there is a need for a team, identify which of the four types is required.

Step 3: Design. Recruit team members, orient them, and operate with clear expectations, role, authorities, and processes.

What leadership and culture are needed? How do we diagnose the current state, and how do we improve it?

Most observers agree that culture and leadership are key factors in attaining organizational health and productivity. Defining these qualities and the methods for strengthening them, however, is a more elusive undertaking. Fortunately, we have numerous examples of excellence in both areas to draw on. The frameworks in this section tend to reflect best practices, emphasizing balance and adjustment to situational requirements.

The leader needs to match their leadership behaviors to the performance level of the individual or group. This is really a follower-driven model, not a leader-driven model.

This helps people figure out if organizational leadership needs to be more like Genghis Khan or Mr. Rogers; we find that pretty important!

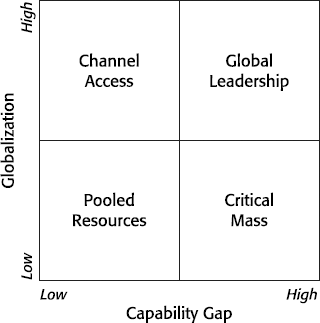

After spending years trying to prove otherwise, the preeminent leadership researcher Ralph Stogdill concluded in 1948, "A person does not become a leader by virtue of the possession of some combination of traits."[90] This acknowledgment gave rise to a procession of multifactored, contingency-based leadership models. The best-known and most widely used of these is Situational Leadership, formulated in 1969 by Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard (Figure 7.7). Situational Leadership maintains that leader effectiveness depends on matching style with task requirements and follower maturity level. The model focuses on behavior rather than attitude.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Situational Leadership matrix explores two key dimensions: Relationship Behavior and Task Behavior:

Relationship Behavior. Relationship behavior refers to the extent to which leaders are concerned with the socioemotional needs of staff, encourage progress, and actively listen.

Task Behavior. Task behavior refers to the extent to which leaders initiate, define, plan, and organize work.

The Four Quadrants. The Situational Leadership model allows leaders to quickly map followers' task-specific performance into four readiness levels, each demanding a different leadership style. It can also be used by external parties such as recruitment firms and human resource departments to identify hiring priorities when filling management vacancies. The action required of the leader defines each quadrant as a uniquely different leadership style.

What sets this model apart is its recognition of differences among those who are to be led. Staff exhibit varying degrees of readiness, and this determines which of the four leadership styles will be most appropriate. If followers are unwilling or unable to take responsibility, the Telling style of leadership is most appropriate. If they are fully capable of doing the work and willing to accept responsibility for the task, the Delegating style of leadership is the best fit:

Upper left: Participating. Followers are able but unwilling to be responsible. Participating and development are needed to coach and reassure the person whose motivation and focus are flagging.

Lower left: Delegating. Followers are willing and able to take responsibility. The leader recognizes their ability by showing trust and maintains a less active role and relationship with them. Delegating works for both parties, increasing scope for development and job satisfaction for the employee, while freeing the leader to focus on other tasks.

Lower right: Telling. Followers are unable and unwilling to take responsibility. A strong, directive leadership style is needed. Intimidating or overwhelming tasks are two examples where a Telling approach is recommended.

Upper right: Selling. Followers are unable but willing to take responsibility. Task direction is coupled with socioemotional support and rationale for why work needs to be completed in a particular way.

Example: U.S. Army. The U.S. Army recruited approximately 79,500 young men and women in 2002, creating a standing force of 475,000 soldiers. Recruits enter untrained and unskilled, and over a period of several years they progress from this state of relative ignorance to readiness for the two basic situations the army must face: war and peace. These different contexts present a challenging set of demands, calling on sensitivity, awareness, and leadership competencies at the highest level.

The years following the Vietnam War and the Persian Gulf Conflict were extended periods of peace. During these eras, retention and development of talent depended on offering meaningful growth and interesting assignments without the looming threat and the experience of waging war.

Conflicts in Yugoslavia and the Middle East have once again forced a return to the primary war role and capability. But turning on a dime from peace to war is not easy.

Situational Leadership helps to determine the appropriate leadership style for different contexts and to define the leadership competencies most required by army officers (Figure 7.8). In peacetime, recruits move quickly from the Telling style of being led to the Selling mode, where a primary goal is to retain the motivation and loyalty of troops in the face of minimal external danger and demand. In the case of high-potential officers, the Participative style is needed to tailor development opportunities to the individual.

In wartime, it is essential that soldiers can operate in the Telling mode, where command and control direction is often mandatory. There isn't much time for Selling, except when will is flagging and troops need inspiration; think of Churchill in the most trying periods of World War II and, more recently, Norman Schwarzkopf in Desert Storm. For certain high-risk missions, total Delegation is necessary as teams operate independently.

Context. Situational Leadership is used by managers to plan how to approach a given subordinate and by executives and human resource specialists when determining how to hire managers and leaders for a team.

Method. An early version of the Situational Leadership questionnaire was published in the May 1976 issue of Training and Development Journal. Twelve multiple-choice questions help to identify one's preferred leadership style and the level of staff readiness. The object of the exercise is to match leadership style with the unique needs of each staff member.

Since that time, Hersey has continued to update the original work and published new versions of diagnostic survey tools. At its most basic, here is how to apply the Situational Leadership framework:

Step 1: Assess. Assess the readiness of each member of a work group for specific tasks. Readiness refers to the Ability to complete the required task assignment and Willingness. Assessment can be done with the help of a Situational Leadership survey tool or by carefully and systematically appraising the readiness of each individual.

Step 2: Evaluate. Locate all the workers on the grid to reflect their relative Readiness.

Step 3: Assess. Assess the manager's style of leadership. The first step in being able to vary your leadership approach is gaining awareness of what you are currently doing to succeed. The manager may be generalizing this method across all staff and situations, meeting with the greatest success where his or her natural talents and inclinations are well suited to the situational needs.

Step 4: Design. Review each of the staff relationships, and construct a plan to address situational needs. Recognize that some cases may place role pressures on the leader or even the larger work system. Performing a variety of leadership functions depends on several things: awareness of staff needs and one's preferred style, agreement by both parties to play reciprocal roles in a respectful and sincere way, and competency on the part of the leader to provide different forms of leadership. Leadership coaching and training may be required to help the manager successfully behave differently.

Step 5: Review. Before implementing leadership plans, it is important to step back to regard the larger leadership and organizational landscape you have created. A solution at one level can create organizational or work design problems elsewhere. For example, a manager can support a wide span of control if most work is delegated to mature professionals who operate independently. If the leadership solution involves lots of coaching, a new level of supervision may be required to relieve the time burden being placed on the manager.

Many putative "leaders" fondly imagine they are running their organizations when all they are doing is allowing them to run themselves. They do not understand the power play at work and are measuring the wrong things.

Formal roles and processes often take a back seat as organizations become increasingly dependent on knowledge.[92] Resentments and misunderstandings can easily occur in such environments, as individuals perform their tasks with only limited awareness of their impact on the firm and those in other positions. Karl-Erik Sveiby, one of the founders of the Knowledge Management movement, argues for higher awareness and conscious management of the interchange between the four fundamental roles that tend to arise in such contexts. Both Professional (content) and Organizational (process) Competencies are necessary and in the right balance (Figure 7.9).

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Four Power Players matrix explores two key dimensions: Professional Competence and Organizational Competence:

Professional Competence. This refers to the content of the business, the company's core value proposition.

Organizational Competence. This consists of administrative, communications, and related maintenance functions.

The Four Quadrants. The dimensions represent the two knowledge traditions that can be found in most organizations. These traditions must find a way to coexist constructively and respectfully:

Upper left: The Professional. Knowledge businesses as typified by the consulting firm are built around this role. Customers demand their expertise. They represent the essential value of the business in the marketplace. Professionals thrive on solving thorny problems. They dislike routine and solving problems the same way over and over. This tendency creates tension with the administration and those trying to increase productivity: the managers. Professionals often appear to be self-absorbed and thoughtless about administrative needs. Operating with a different sense of urgency and purpose, they are however capable of higher levels of consideration and collaboration when informed and appropriately motivated.

Lower left: The Support Staff. Success in professional firms often depends on freeing up front-line staff from administrative and detail work. Support staff play the crucial role of handling the many tasks that are not dependent on professional expertise but are nonetheless critical. There is a tendency for these people to fall out of the communication loop and resent others, principally the professionals, who often display little sensitivity to organizational rules and needs.

Lower right: The Manager. Managers have designated authority to make sure work is coordinated and completed in a sustainable and acceptable way. They are responsible primarily for the organizational priorities of the firm, making it possible for others to be creative and client centered. Managers work through other people, in contrast to professionals, who work with other people. Managers therefore often find themselves at loggerheads with the professionals.

Upper right: The Leader. Leadership provides direction and passion that defines and drives the business. In knowledge-based firms, leadership does not always come from formally designated leader roles, and it can be more difficult to assert. Nonetheless, it is essential. A prime task of formal leadership is to provide professionals with the conditions to exercise their creativity for the benefit of customers. Because of the enormous and often conflicting demands, some successful companies split this role. For example, one person may be in charge of professionals, while someone else is responsible for marketing and administration. Leadership in a newspaper, for example, is divided between the editor and the publisher.

Method. The framework is useful for diagnosing and clarifying individual roles and organizational balance. Problems arise when roles are missing or are not being well executed:

Step 1: Assess the need for the four primary functions (more, less, or okay as is)?

Step 2: Identify who is in each role.

Step 3: Assess the effectiveness of each function.

Step 4: Assess the health of the relationship between the roles.

Step 5: Make adjustments to improve within the four functions or between the functions.

Sveiby, K.-E. The New Organizational Wealth: Managing and Measuring Knowledge Based Assets. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1997.

Plotting the way that a leader works on a simple two-dimensional continuum like the following (Didactic

Training groups are settings where participants improve life skills of a primarily social and leadership nature.[94] Effective leadership of such groups calls for a balance of intellectual content—didactic instruction—and participatory self-discovery—facilitation (Figure 7.10). Leaders need to develop both of these skills and learn when each is most appropriate.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The T-Group Leadership matrix explores two key dimensions: Didactic and Facilitative:

Didactic. This is a content-oriented, telling orientation. The teacher is the expert who imparts a predefined body of knowledge to students.

Facilitative. This is an experiential, helping orientation based in observation, process, and sharing of responsibility. The agenda is generated in a here-and-now manner, and the way solutions are achieved is often more important than the solution itself.

The Four Quadrants. Leaders need to match their role with what is required in the situation. In any training group, a certain amount of tension between the didactic and facilitative emphasis is inevitable:

Upper left: Content Leadership. Content leadership employs a traditional teacher-student approach. The teacher is in control and responsible for defining and imparting knowledge. This approach is appropriate for phases of learning and under certain circumstances, such as large classes.

Lower left: Leadership Abdication. Leaders who are too invisible add little, frustrating the group and wasting time that could be spent productively. Leaders need to take responsibility for their role and contributions.

Lower right: Process Leadership. Process leaders focus on the moment, with the group interaction setting the agenda. This approach is most useful when working with small, intact work teams where the goal is performance effectiveness.

Upper right: Balanced Leadership. Learning needs change dynamically in training groups. At one moment, the priority is making sense of an incident, calling on high facilitiative skills; at the next moment, it is acquiring a deeper understanding of a concept like trust or interpersonal conflict, calling on didactic mastery. Excellent training group leaders have developed both competencies.

Method. Leaders increase their effectiveness by matching their approach to situational requirements:

Step 1: Diagnose. Consider the learning needs and capabilities of team members.

Step 2: Design. Prepare experiential design and materials in accordance with needs.

Step 3: Deliver. Deliver the training, monitoring success and adjusting as necessary.

What new competencies are needed? What change is required? How do we manage the change?

The old saying, "If it ain't broke, don't fix it," has been replaced with the metaphor of "perpetual whitewater." At times, it really does appear that the only constant left is change. Adjusting to this state of affairs, organizations are building more flexible roles and structures and designing business processes that deliver just-in-time value to minimize waste and excess inventory.

Learning is a key enabler of change. In some businesses, training and development is a fully integrated function, preparing staff well in advance of change initiatives. Too often, though, it is an afterthought, competing with other tasks for scarce time and attention.

Frameworks in this section address the two topics of learning and change as an integrated whole, underscoring their interdependency.

In an economy where the only certainty is uncertainty, the one sure source of lasting competitive advantage is knowledge.

The notion of tacit knowledge in the SECI model (named for the four forms of knowledge conversion identified in the matrix: Socialization, Externalization, Combination, and Internalization) is based on the work of philosopher Michael Polanyi, who in 1966 classified knowledge into two categories: tacit and explicit. For Polanyi, knowledge that could be expressed and stored in words and numbers represented a small portion of human knowledge. The greater part represented hunches, intuition, values, images, beliefs, principles, and mental models of the world that enable us to work and socialize effectively. In 1995, Ikujiro Nonaka and Hirotaka Takeuchi published the SECI model (Figure 7.11) to help people understand how tacit and explicit knowledge interact within organizations and how the management of those interactions, which they called knowledge conversions, could be a source of competitive advantage. Their subsequent publications expanded on this model, and their insights have had a profound effect on how corporations now think about knowledge assets and knowledge management.[96]

Corporations have been receptive to this message, and for good reason. Over the past fifty years, the balance of value within firms has shifted from physical assets to intangible knowledge assets. When combined with the impact of increasing global competition, this has forced a fundamental change in organizational structure, from vertical, hierarchically integrated firms to ones that are increasingly horizontal, flat, and modular.

In the traditional model, work was conceived at the top of the hierarchy and executed at the bottom. Information flowed quickly down and not so quickly back and forth and up the chain of command. It is increasingly clear now that the knowledge that management seeks to control is created and leveraged daily by personnel throughout the organization, including unskilled, manual, and clerical workers.

In order to get their jobs done, workers continually create new knowledge. When they hit roadblocks, they invent solutions: they figure out how to operate equipment more efficiently, work around technology problems and design flaws, solve customer issues, and coax productivity out of informal organizational networks. Nonaka and Takeuchi's SECI matrix provides a systematic way of viewing the life cycle of knowledge development and transfer among workers within the firm.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The SECI matrix explores two key dimensions: Tacit Knowledge and Explicit Knowledge:

Tacit Knowledge. Tacit knowledge is highly personal and difficult to share. How do you communicate physical skills like becoming a master glass blower or learning how a second baseman makes a double play? How does a mother sense the needs of her child before they are expressed? And how does your most skilled computer technician diagnose problems in seconds that might take others hours? As Larry Prusak, executive director of IBM's Institute for Knowledge Management, says, "Knowledge is sticky, staying close to individuals and contexts."[97] Most of these kinds of knowledge don't translate quickly through books and computers. They are embedded in us as a result of our life experiences and the skills we practice on the job.

Nonaka and Takeuchi define two aspects of Tacit Knowledge: the cognitive and the technical. In the cognitive dimensions are the beliefs, ideals, and views of the world that are so deeply ingrained in us that we are frequently unaware of them. By shaping the way we see ourselves and the world around us, the cognitive dimension provides a foundation for all our interactions. The technical dimension refers to skills and know-how and personal ability to get our jobs done that have been set in place through long experience and practice.

Explicit Knowledge. Explicit Knowledge consists of knowledge that we communicate in formal language. It is discrete and can be captured and transmitted digitally. It can be encoded in a wide range of forms, such as books, manuals, and electronic databases.

The Four Quadrants. Each type of knowledge can be converted. When viewed as a learning process, the SECI matrix takes the form of a spiral. The four stages of knowledge conversion describe how organizations create, manage, and transfer knowledge. In the upper left, the process starts with Tacit "sympathized" Knowledge, hard-won worker skills that must be shared and socialized to become Explicit "conceptual" Knowledge (upper right). Once converted to Explicit Knowledge, it can be combined and integrated into explicit forms that can be shared throughout the organization. As workers reinternalize what they learn, it becomes Organizational Knowledge (lower left), part of the shared knowledge of the firm. Ultimately, newly trained workers begin to practice their skills on the job, slowly turning Explicit into new Tacit Knowledge over time (upper left):

Upper left: Socialization (Tacit to Tacit). Socialization involves capturing knowledge through physical proximity and direct interaction with people. It is a Tacit-to-Tacit exchange. For example, people who work with mentors learn by observing, children watching their parents learn through imitation, and students watching an artist or craftsman at work learn by practicing what they have seen done by others. When we share physical space, activities, and experiences, we find numerous ways to learn from one another.

Lower left: Internalization (Explicit to Tacit). Internalization refers to the conversion of Explicit Knowledge into the organization's Tacit Knowledge. In this stage, workers learn by doing and by training, turning the organization's wisdom into skill and knowledge of their own. They internalize the knowledge and increasingly rely on their own skills and judgment.

Lower right: Combination (Explicit to Explicit). Combination is the conversion of Explicit Knowledge to new Explicit Knowledge. There are three main elements: combination, dissemination, and processing. First, Explicit Knowledge is captured and combined with other knowledge to create deeper, more complex levels of understanding. For example, a strategist who purchases an outside research report and integrates it into a strategy document she is writing is creating new Explicit Knowledge from two prior sets of explicit information. In the dissemination phase, the organization attempts to disperse the new knowledge through internal publications, meetings, and other processes. Finally, in the processing stage, new knowledge is edited internally into strategies, plans, and reports that make it easier to share and apply within the organization.

Upper right: Externalization (Tacit to Explicit). Externalization is the stage of Tacit-to-Explicit information conversion. Articulating Tacit Knowledge in forms that others can understand—words, concepts, instructions, figurative language, and pictures—externalizes it. In practice, this often occurs though dialogue with others (work groups) and creative techniques such as hypothesis development using metaphors and analogies.

Example: Communities of Practice at Xerox. Many firms today face the complex challenge of maximizing the long-term value of Tacit Knowledge. Operational knowledge, as in processes such as check cashing and auto assembly, can be codified, reengineered, and taught to others. But how do you transfer craft skills and insights? For example, if you wanted to become a master consultant, the best way to do that would be to work with one. In fact, this is exactly the approach taken by firms such as McKinsey, which believe that young recruits must spend lots of time with top consultants in order to learn the client management and creative conceptual skills that lead to success in their business.

Companies such as Buckman Laboratories, Xerox, and Johnson & Johnson are among the leaders in the emerging field of knowledge management. At these companies, a great deal of effort goes into supporting communities of practice: groups of people who share similar goals and interests and employ common tools and language in performing their work. The problems they experience are common, and they work together to learn and create solutions. In reality, a community of practice may be a far-flung virtual group of programmers or an in-house marketing team drawn from many disciplines. The output of communities of practice is knowledge as well as social capital—norms of trust, reciprocity, and citizen participation. As workers come together in an organic fashion to solve problems, they improve the overall efficiency of the organization. As the technology for global cooperation has improved, firms are finding it easier to foster collaboration that serves customers and empowers employees to take the lead in creating and converting new kinds of knowledge.

John Seely Brown, chief scientist of Xerox, relates the story of how communities of practice were developed among the company's repair technicians beginning in the early 1990s. When he was asked to design knowledge systems for technicians, he began by asking anthropologists to study the activities of the people in the field. He wanted to know how they learned and shared information. The main finding was that when a problem was encountered, a technician would call another technician and tell him the "story" of the machine (Figure 7.12). They would then share story "fragments" about other repair experiences, weaving a narrative together until they arrived at a solution for how to fix the machine. Storytelling continued when technicians got together for coffee and doughnuts in the morning before going into the field, serving as an informal method through which best practices were shared.[98]

To leverage this knowledge further, Brown created a community of practice by providing field technicians with two-way radios. These were always on, so the reps remained connected to their own instantaneous community of experts. Although this helped individual technicians improve their work in the field, it did nothing to improve the learning of technicians across the rest of the firm.

Brown was challenged to create a system that tapped the minds of the community of practice, not just the mind of one expert technician. In response, he and his team deployed a system they called Eureka, which enabled technical reps to share their stories over the Web. Periodically, specialists would validate the stories. In this way, individuals with specific knowledge became known to the whole community, and answers to very specific questions became available globally as soon as they were discovered. Brown estimates that learning increased 300 percent and saved Xerox up to $100 million per year.

Context. The SECI matrix is useful for raising awareness of how knowledge is managed in an organization. This awareness can be factored into the design of knowledge-sharing strategies and systems to improve knowledge creation, storage, and exchange practices. Each of the quadrants represents a diagnostic category and improvement opportunity to explore.

Method. Try the method that follows to examine an area of practice in your organization:

Step 1: Define. Identify an aspect of organizational performance where there is a knowledge issue or gap.

Steps 2–5: Diagnose. Examine and improve by tracing the handling of knowledge in this area through the knowledge life cycle by following the four phases of the SECI:

Upper left: Who has the knowledge? How is it shared or socialized?

Upper right: What mechanisms exist to make the knowledge explicit in the firm? Who is responsible for that?

Lower right: How is knowledge about this aspect of organizational performance synthesized with knowledge from other sources outside the firm? Where and how does that happen?

Lower left: What processes are in place to train and support further internalization of this new knowledge?

Step 6: Envision the payoff. Answer the question: How would the improvement in knowledge capture and transfer lead to higher levels of performance within the firm? Cost reductions? Time savings? Quality improvements?

Brown, J. S., and Duguid, P. "Organizational Learning and Communities-of-Practice: Toward a Unified View of Working, Learning, and Innovation." Organization Science, 1991, 2(1), 40–57.

Nonaka, I., and H. Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Nonaka, I., and Toyama, R. "A Firm as a Dialectical Being: Towards a Dynamic Theory of a Firm." Industrial and Corporate Change, 2002, 11, 995–1009.

Random hiring of Ph.D.'s won't cut it. What are you going to do with them? Human capital needs its customer and structural siblings to make a difference.

Thomas Stewart, executive editor of the Harvard Business Review, is one of the pioneers of the Knowledge Management movement and the author of two of its most important books, Intellectual Capital (1997), and The Wealth of Knowledge (2001). Intellectual capital, comprising human, structural, and customer components, is the new driver of competitiveness. The year 1991 was pivotal: worldwide investment in intangible information technologies (such as computers, telephones, and personal digital assistants) overtook money spent on machines (farm machinery, factories, metal, and plastics, for example) involved in the production of tangible products. As the "weight of value" continues to decline, it becomes increasingly important to create meaningful ways to define, identify, develop, manage, and measure these intangible assets.

Stewart makes the argument for strategic management of three primary forms of intellectual capital: human, structural, and customer. In the domain of human capital, certain types of knowledge assets hold much higher value to firms than others. By focusing on two criteria, Difficult to Replace versus Important to Customer, businesses can determine the relative importance and difficulty of the replacement of its business functions and the competencies they depend on. The Human Capital framework (Figure 7.13) offers a clear and useful method for organizations to assess operations and determine the best treatment of divisions and positions throughout the company.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Human Capital matrix explores two key dimensions: Difficult to Replace and Important to Customer:

Difficult to Replace. Some skill sets are more difficult to replace than others. Jobs based on scarce competencies (such as cardiac surgery) or unique knowledge about the business (such as auditing and communications) are higher in this regard than those consisting of repetitive, procedural work (for example, assembly line worker, cleaning staff). This dimension is primarily indicative of the importance of a role within the organization as opposed to representing a customer perspective.

Important to Customer. Certain competencies in the firm are more directly tied to customer value creation than others. Those aspects of value that attract and reinforce customer loyalty are central to a firm's identity and competitiveness.

The Four Quadrants. "A company's human capital," writes Stewart, "is in the upper-right quadrant, embodied in the people whose talent and experience create the products and services that are the reason customers come to it and not to a competitor. That's an asset. The rest—the other three quadrants—is merely labor cost."[100]

By considering Human Capital in the same way we treat other corporate assets, firms can make better strategic choices about organizational structure, recruiting, and training. Difficult to Replace and Important to Customer are two defining characteristics of all the roles and employees in an organization. Applying this framework demands a degree of analytic dispassion, favoring the needs of the business over those of individuals. As Stewart points out, it doesn't really matter if your employees are all brilliant or extremely hard working if they are producing nonessential results. The Human Capital framework places the focus on organization design and strategic deployment of staff, increasing the value of their output. As the framework indicates, the goal is to upgrade the value of the firm's Human Capital by directing it either up and to the right or out of the organization through options such as outsourcing or automation:

Upper left: Informate. Businesses rely on the contributions of staff functions that are complex, nuanced, and take time to learn. Although it is difficult to replace these individuals, their work is often underleveraged and invisible to customers. Customers don't really care about internal audit, billing, or complex factory process work unless they are done wrong. The strategic interest in this quadrant is to derive additional benefit from a functional activity. Informating a task means enriching it with added-value education or service. This is what GE did a few years ago when it redefined and augmented its internal audit process, changing it from mere numbers checking to a consultative service providing useful feedback and best practices advice. Another example is the move to equip call center staff with better customer intelligence tools, allowing them to target and deliver personalized value to callers based on their characteristics and likely needs.

Lower left: Automate. Many businesses find themselves somewhat dependent on low-complexity, semiskilled workers. Although the success of the business may indeed depend on the contributions of these employees, the individuals hired to do the work are interchangeable and easy to find. McDonald's and most of its competitors have designed their outlets with this in mind. The most basic repetitive work is automated out of the process. The remaining tasks, like food preparation and order taking, are routinized so that low-salary staff can be quickly trained and deployed as required. McDonald's, for example, is able to function smoothly in spite of annual turnover rates ranging geographically from 50 to 300 percent.

Lower right: Differentiate or Outsource. Some work is extremely high in value yet not identified directly with specific individuals. Consider the cover design of a book or quick technical support provided to users of a piece of computer hardware or software. Although these services are vital to the success of a business, they can be found fairly easily. Firms can consider two actions to increase the value of this category. The first is Outsourcing such a service, which can be economical while permitting the company to focus its energies on other more essential and differentiating activities. Firms can afford to be world class in specialized areas like logistics and product assembly by moving the function to a trusted strategic partner like UPS or Solectron.

Differentiating occurs when a set of generic capabilities is organized and packaged as an integrated offering at a higher level of perceived value. A clear example is the migration of computer hardware and software companies to the consulting and information technology systems solutions business.

Upper right: Capitalize. The upper right quadrant is the target zone where companies should concentrate their Human Capital. These are the prime innovators, leaders, and service providers working at jobs that differentiate the firm and delight customers. They span roles like research chemist, top sales representatives, and movie stars. As the percentage of a firm represented by this category increases, its competitiveness and relative value rise.

Example: The Metamorphosis of the Automotive Industry. Early in the twentieth century, the Ford Motor Company became the dominant global automobile manufacturer when it introduced its famous moving assembly line. A rope would pull the vehicle along, making it possible for fifty employees to remain in fixed positions and add their defined contribution in a controlled and efficient manner. The time it took to build one Model T dropped from twelve hours to one and a half, and the cost fell from $850 to $250.

With this amount of improvement, the vertically integrated business firm model became standard in the industry. Ford's Rouge River manufacturing plant was famous for the depth of its value chain, ranging from rubber plantations in South America for tires to glass manufacturing facilities. While General Motors offered a wider set of product selections than its main competitor did, it followed a similar business architecture and vertical culture. When GM president Charles Wilson was being considered for the position of secretary of defense for the United States in 1953, he was asked if he thought his position with GM might cause some conflict of interest. He replied, "I cannot conceive of any because for years I thought what was good for our country was good for GM and vice versa."[101]

The tightly integrated philosophy and business structure that made this response possible continued to dominate the industry well into the second half of the century. Improved communications and collaboration technologies eventually transformed this. Today, all the major auto companies are global; they are sourcing, manufacturing, and selling around the world. A well-established system of suppliers and the movement toward standardized parts and communications has resulted in a much more open and horizontal industry model.

The automotive industry took on a whole new shape as production technologies and communications systems improved (Figure 7.14). Companies and whole subindustry groups formed to offload portions of value creation at attractive prices and terms.

Repetitive manual work and mindless reminders and tracking functions have been automated out of the human part of the system. Most modern auto plants make extensive use of robotics and smart quality process control technology.

Internet-based problem-solving systems make the best company experts' knowledge available to customers, informating talent that was previously hidden inside the organization. Other services, like leasing and sales information, have undergone a similar change.

Probably the greatest amount of change has occurred in the work falling in the lower right quadrant. Outsourcing and strategic partnering now account for a significant share of the automotive value chain. The creation of Covisint in 2000 by GM, Ford, and Daimler Chrysler as a common electronic trading environment has accelerated the growth of partnering within the industry. Daimler Chrysler estimates that close to 70 percent of its suppliers are now on-line via Covisint and applying a common quality management tool called Powerplay.com. EDS, at one time owned by GM, still provides the vast majority of its information technology services.

Increasingly, the role played by the automotive company itself is of a knowledge-intensive and strategic nature. Customer relationship management and positioning and caring for the brand are core assets carefully comanaged with the dedicated dealer networks. Design and marketing of the vehicles is central to differentiation, as is business and pricing strategy. As in other manufacturing industries, increasing amounts of production are treated as a commodity service that can be outsourced, leaving the company free to concentrate on planning and coordinating the inputs of low-cost specialist partners and suppliers.

Contexts. The framework is useful for firms engaged in strategic improvement exercises or when they are considering outsourcing functions.

Method. A Human Capital review and design process helps a company to understand and improve its deployment of talent. Each of the steps here can be completed in a variety of ways, depending on who does the work and how extensive the redesign needs to be. For example, in step 2, a single person can deliver a high-level set of recommendations, or one work group can be established for each of the four quadrants to conduct a fuller set of reviews and proposals:

Step 1: Analyze work. Analyze work done within the organization, placing all functions and roles in question into one of the four quadrants.

Step 2: Identify improvement opportunities. Explore opportunities to improve the deployment of Human Capital within each of the three suboptimal quadrants. For example, how can work falling into the upper left quadrant be informated, or that in the lower left be automated?

Step 3: Create improvement plans. Prepare a set of recommendations and plans for Human Capital improvements, and prioritize these for desirability and feasibility.

Step 4: Enhance key assets. Consider how the human capital in the upper right quadrant can be enhanced as well as protected.

Stewart, T. Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations. New York: Currency, 1997.

Stewart, T. The Wealth of Knowledge. New York: Currency, 2001.

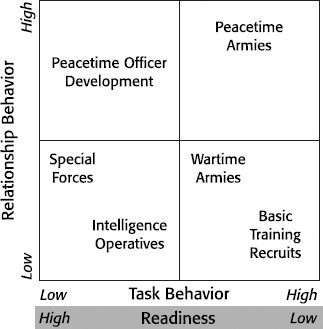

Development of an organization is a purposeful transformation toward higher levels of integration and differentiation at the same time.

Systems thinkers see organizational and cultural development as a balancing act between the proliferation of new ideas, entities, and behaviors and the effective integration and management of these things. The corollary is simple: as the rate of change and differentiation increases, the need for integration rises in kind (Figure 7.15).

Healthy organizations and societies encourage individual initiative and development, while ensuring coordination of efforts and sharing of knowledge. Social systems of all varieties are in a constant process of change, slight or extreme. In times of greater turbulence, both positive and negative, more change is called for. Recall the economic and political upheaval in the former Soviet Union or the rush of creative competition in Silicon Valley during the 1990s. When the rate of change outstrips a system's ability to integrate it, the effect can be overwhelming and destructive, leading to failure and dysfunctionality. When both forces are working together, progress can be exhilarating, as occurred in Europe during the Rennaisance and in the operation of excellent companies like Dell and GE.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The matrix explores two key dimensions: Differentiation and Integration:

Differentiation. Differentiation is the pursuit of new and diverse directions for growth and development. This is essentially artistic in nature, leading toward greater complexity and autonomy for the parts of a system.

Integration. Integration efforts establish order and stability by creating meaningful trade-offs and links between diverse system elements. The orientation is more scientific, emphasizing rationality, instrumentality, and conformity.

The Four Quadrants. With the introduction of energy and intention, systems evolve from simple to complex and from chaos to order. This process, called negentropy, is a prime feature of living systems and assumes a reasonable amount of balance between creative (Differentiation) and synthesizing (Integration) forces. The not uncommon tendency to emphasize one or the other in isolation creates extreme environments in ways that are self-reinforcing. In the worst of cases, the system must approach complete destruction before a reversal of direction can be initiated:

Upper left: Organized Simplicity. This state dominates when forces for control and order prevail at the cost of new ideas and approaches. A form of stability is attained, but it tends to be rigid and authoritarian. Although efficiencies are often realized, energy is lost, and long-term viability is jeopardized.

Lower left: Chaotic Simplicity. This quadrant describes a relatively simple condition with low levels of organization. This might be the case during a period of low demand or, conversely, a system that is at a point of giving up efforts to cope effectively.

Lower right: Chaotic Complexity. Chaotic Complexity prevails when innovation and experimentation are pursued without restraint and accountability. Diversity can overload the system, depleting it of resources and focus. Duplication of efforts, errors, and conflicts are real dangers.

Upper right: Organized Complexity. Healthy progress through experimentation, learning, and integration is achieved by moving concurrently toward higher levels of complexity and order. Innovations are supported in ways that contribute to overall system improvement; knowledge is shared, and self-correction is ongoing.

Example: Health Care Cost Crisis: Butterworth A viable and affordable health care system is arguably a cornerstone of a successful society and a fair measure of its performance. An aging population in the United States is placing increasing demands on an already fragile and overburdened health care infrastructure. As Gharajedaghi observes, "The present health care system has its origin in sickness care."[103] People expect access to adequate care in a reasonable time frame at a price they can afford.

A series of payment and service delivery options have been spawned, including fee for service, health maintenance organizations (HMOs), independent (self-insured) companies, Medicare (for those over age sixty-five), and Medicaid (for those lacking means). Although these are helpful measures, the combined effect of these approaches has been an escalation in patients' expectations, with little countervailing pressure to limit demand.

Butterworth Health Systems is an HMO operating in the Grand Rapids, Michigan, area. Recognizing the symptoms of an accelerating gap between patient expectations and the affordability of care, a search for new alternatives based on an understanding of needs and limits was initiated. The four quadrants in Figure 7.16 describe the evolution of responses that Butterworth and other HMOs have attempted.[104]

The lower left quadrant, Streaming, describes the early years of operation. In this phase of its existence, the facility served a defined segment of the population. The lower right quadrant, Overwhelming Reactive, describes unsuccessful efforts to creatively accommodate a multitude of expectations and payment mechanisms. It was clear that order needed to be achieved to maintain system viability, pushing the organization to the upper left quadrant, Enforced Compliance.

Added pressures on the system led to efforts to Enforced Compliance as a way to control and manage demand. The system was becoming at once increasingly bureaucratic and mechanistic, while remaining incapable of meeting expectations with the existing resources and funding arrangements. Gharajedaghi writes, "HMOs have been forced to use a bureaucratic system and a mechanistic mode of operation to manage the most emotional and sensitive behavior of a human system of health care."[105]

Option 4, Preventive Proactivity, came about through a design exercise in 1996 led by INTERACT (a Pennsylvania-based consultancy where Jamshid Gharajedaghi is managing partner and CEO). The distancing of patient need from payment responsibility was driving expectations beyond the service ability of the company within funding levels set by payment bodies like insurance companies and governments. By promoting health and illness prevention, Butterworth was able to reduce the volume of higher-cost acute care demand from patients. The solution (in reality more complex than this description) helped to transcend the stuck place where all options appeared to be unworkable by appealing to a more primary aspect of self-interest of the system beneficiaries, the patients.

Context. Differentiation and Integration is part of a design approach that offers a powerful and intuitive method for social system redesign. It is effective as a timely and nonthreatening intervention to prevent excessive chaotic or bureaucratic buildup. Due to its structure, it scales easily from serving as a convenient context for reflecting on a situation to a more structured and systematic program approach.

Method. The systems approach to organizational improvement models the whole and all its parts in dynamic relationship. A systems intervention is sensitive to balancing degrees of Differentiation and Integration, proceeding in a series of iterations toward a more desirable state that is feasible and supported. INTERACT's approach has the following characteristics:

Problem definition and solution building are distinct and separate processes.

Stakeholder buy-in is important.

Design occurs at three interdependent system levels: structure (inputs, means, causes), function (outputs, ends, efforts), and process (know-how, sequence of activities).

The output of an intervention is a new architecture that enables desired performance and benefits and resolves or eliminates defined problems.[106] Guided by an understanding of systems principles, an intervention follows a three-phase sequence:

Step 1: Understand the context.

Step 2: Define the problem.

Step 3: Design the solution.

Gharajedaghi, J. Systems Thinking: Managing Chaos and Complexity. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann, 1999.

Put another way, one cannot impose cooperation on another without a fight, or at least so it seems.

Conflict is inherent in living systems and is not always a problem needing to be solved. Healthy, adaptive systems effectively harness the knowledge and energy of diverse parties. Russell Ackoff first modeled the dynamics of Means and Ends (Figure 7.17) in his 1972 book, On Purposeful Systems. Interdependent parties are motivated by the Ends they pursue, with conflicts resulting where Ends are or appear to be incompatible with those of others. The Means whereby Ends are achieved may also be more or less compatible with those of other interested parties. By addressing these issues, negative conflict can be better understood and reframed into more constructive forms of relationship.

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The matrix explores two key dimensions: Means and Ends:

Means. These are the methods we employ to achieve desired outcomes.

Ends. These are the goals and objectives that we value.

The Four Quadrants. Problem solving and design occur in a series of iterative waves, calling on four sets of activity, each with an associated skill set:

Upper left: Coalition. Coalitions are formed by competitors to address common, usually short-term problems or adversaries. We find these arrangements in wars, industry, and interpersonal dynamics. A truce is called to focus on the shared threat, after which the parties may well return to conflict.

Lower left: Conflict. Parties that disagree about both Ends and Means are stuck in Conflict. These situations can become increasingly polarized, resulting in zero-sum, win-lose outcomes. Communication and reframing help improve conflicts. In On Purposeful Systems, Ackoff suggests three ways to address Conflict: solve, resolve, and dissolve.

Lower right: Competition. In Competition, lower-level conflicts provide a useful context for realization of the interests of different parties. Companies within an industry compete against each other for customers yet share the need to educate the public about their collective value proposition. Healthy Competition often creates the most positive conditions for growth and mutual success.

Upper right: Cooperation. Parties Cooperate when both Ends and Means are compatible. In Cooperation, it is assumed that each party contributes positively to the success of the other.

Method. The framework is useful in transforming unhealthy Conflict situations through dialogue, awareness, and reframing:

Step 1: Identify the Ends and Means of the parties involved.

Step 2: Identify the quadrant that best describes the situation.

Step 3: Creatively investigate the possibility of redefining the Means or Ends of either or both parties to improve the relationship and likelihood of a positive outcome.

Ackoff, R. L. On Purposeful Systems. Seaside, Calif.: Intersystems Publishers, 1972.

Ackoff, R. L. The Art of Problem Solving. New York: Wiley, 1978.

Gharajedaghi, J. Systems Thinking: Managing Chaos and Complexity. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann 1999.

It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but rather the one most responsive to change.

As individuals and as members of groups within organizations, we all experience losses and need to cope with change. Elizabeth Kübler-Ross provided the basic model for understanding and dealing with such change in her seminal 1965 book, On Death and Dying. Drawing on interviews with terminally ill patients, she identified a series of five common stages of grieving and adaptation: denial, anger, depression, negotiation, and acceptance. These insights are applied in the Change Grid model (Figure 7.18) by various change management experts.[109]

The Two Dimensions and Their Extremes. The Change Grid explores two key dimensions: Focus and Time:

Focus. Attention is placed primarily on the External world of relationships, events, and things or on the Internal world of feelings and ideas.

Time. Attention is directed primarily to Past events or Future possibilities.

The Four Quadrants. Adjusting to change as we move from Denial to Commitment takes time. The severity of the change and individual differences affect how quickly one will move through the cycle and return to normal balance. Resiliency is improved by focus, positive outlook, flexibility, organization, and proactivity:

Upper left: Denial. Our first reaction to negative news is disbelief and rejection. It may simply be too much to absorb. Recognition makes it somehow more real. Virginia Satir, author of Conjoint Family Therapy, describes this as a disruption of the status quo, which is uncomfortable and threatening. Anger is often expressed at this stage.