CHAPTER SIX

DEVELOPING THE CAPACITY TO INNOVATE

IN JONATHAN SWIFT’S SATIRE Gulliver’s Travels, Gulliver visits the land of Laputa, where he tours the Grand Academy and is privileged to examine the department of “speculative learning.”

I had hitherto only seen only one side of the academy, the other being appropriated to the advancers of speculative learning, of whom I shall say something.

The first professor I saw was in a very large room, with forty pupils about him. After salutation, observing me to look earnestly upon a frame which took up the greatest part of both the length and breadth of the room, he said, perhaps I might wonder to see him employed in a project for improving speculative knowledge by practical and mechanical operations. But the world would soon be sensible of its usefulness; and he flattered himself that a more noble exalted thought never sprang in any other man’s head. Every one knew how laborious the usual method is of attaining to arts and sciences; whereas, by his contrivance, the most ignorant person, at a reasonable charge, and with a little bodily labour may write books in philosophy, poetry, politics, law, mathematics, and theology, without the least assistance from genius or study. He then led me to the frame, about the sides whereof all his pupils stood in ranks. It was twenty feet square, placed in the middle of the room. The superficies was composed of several bits of wood, about the bigness of a die, some a bit larger than others. They were all linked together by slender wires. These bits of wood were covered on every square with paper pasted on them; and on these papers were written all the words of their language in their several moods, tenses, and declensions; but without any order. The professor then desired me to observe, for he was going to set his engine at work. The pupils, at his command, took each of them hold of an iron handle, whereof there were forty fixed round the edges of the frame. And, giving them a sudden turn, the whole disposition of the words was entirely changed. He then commanded six and thirty of the lads to read the several lines softly, as they appeared upon the frame; and, where they found three or four words together that might make part of a sentence, they dictated to the four remaining bobs who were scribes. This work was repeated three or four times, and at every turn, the engine was so contrived, that the words shifted into new places, as the square bits of wood moved upside down.

Six hours a day the young students were employed in this labour, and the professor shewed me several volumes in a large folio already collected, of broken sentences, which he intended to piece together, and, out of those rich materials, to give the world a complete body of all arts and sciences; which, however, might be still improved, and much expedited, if the public would raise a fund for making and employing five hundred such frames in Lagado, and oblige the managers to contribute in common their several collections.

He assured me that this invention had employed all his thoughts from his youth; that he had emptied the whole vocabulary into his frame, and made the strictest computation of the general proportion there is in books between the numbers of particles, nouns, and verbs, and other parts of speech.

I made my humblest acknowledgement to this illustrious person for his great communicativeness; and promised, if ever I had the good fortune to return to my native country, that I would do him justice, as the sole inventor of this wonderful machine; the form and contrivance of which I desired leave to delineate upon paper. I told him, although it were the custom of our learned in Europe to steal inventions from each other, who had thereby, at least, this advantage, that it became a controversy which was the right owner, yet I would take such caution, that he should have the honour entire, without a rival.1

In Gulliver’s visit to the Grand Academy of Laputa, Swift shows us an imaginary place where the ridiculous is the norm. He also writes of a researcher who spent eight years extracting sunbeams from cucumbers and placing them in a hermetically sealed vial, to be let out to warm the air in inclement summers. He introduces us to another person who developed an automated system of plowing fields. This fellow’s innovation began by first carefully burying prodigious quantities of acorns, nuts, dates, and other vegetables in the field to be plowed. Hogs would then be turned loose in the field to root up the ground in preparation for sowing a crop. (We have come up with more efficient farming techniques since then.) Swift also shared an endeavor to make clothes by trigonometry. We’re lucky Lands’ End hasn’t heard about the trigonometry method.

Swift’s goal with his tale was to satirize the excesses of his time, in this instance the use of scientific tools and methods for inappropriate purposes. We smile at his wit nearly 300 years later, but even today we’re not immune from using improper tools and inappropriate skills. In this chapter, we explore the development of capabilities for innovation—useful innovation—which will be immeasurably more powerful than those pursued by the Laputans.

STRATEGIC VS. TACTICAL INNOVATIONS

INNOVATIONS CAN BE either strategic or tactical—big-picture, or narrow-focus. The big-picture strategic innovations tend to be those that are measured by their impact in the marketplace. Strategic innovations demand intimate involvement by senior management because only senior management has the power to enact strategic decisions. In addition, such innovations may originate at the highest levels.

On the other hand, tactical innovations are the fiber of continuous improvement initiatives. They are usually smaller in scale than strategic innovations and may be either internally or externally measured. Such innovations can be significant and may produce discoveries that find their way all the way to the boardroom. No organization lives by strategic innovation alone, and we are lucky to have either type of innovation.

In either case, we’re doubly lucky. We don’t require “speculative knowledge” (a wonderful example of an oxymoron).

GETTING THE INNOVATIONS WE NEED

THERE ARE KEY areas of business operations (opportunities) where innovation can have a major impact on a company’s future. If we identify these key areas, we can proceed to developing the capability to innovate in each one.

THE IMPORTANCE OF INNOVATING IN MORE THAN ONE AREA

This brings us to a key point: Of ten diverse trajectories along which major innovations may occur (listed below), the effective organization will sustain innovative success only when it can innovate in more than one area. True, innovations in a single area can produce big gains, but the gains will not be sustainable.

In other words, we need innovation in multiple areas if it’s to produce a sustainable competitive advantage. These might be any combination of strategic and tactical innovations. The assertion that multiple innovations are necessary ups the ante considerably. If we’re to have any hope of producing continuous innovation, the management of that resource must be more holistic, more inclusive. To achieve innovation in a single area is difficult. Achieving innovation in multiple areas is much more so, particularly to get the innovations when you need them. Why are multiple innovations required? There is a straightforward reason: One innovation usually demands another to become fully operational.

Here’s an example. In 1959, Kelly Johnson and his design group at the famous Lockheed “Skunk Works” brought forth the still awesome SR-71 reconnaissance aircraft, the Blackbird. A technological marvel, the Blackbird—even when retired in the late 1990s—remains the most exotic high-performance aircraft (space travel excepted) ever created. It was an aircraft like none ever created before, the first to use the then–state-of-the-art carbon fiber material in copious amounts throughout the airframe.

Using a new material like carbon fiber for making a state-of-the-art aircraft is certainly innovative—so innovative, in fact, that there was no carbon fiber industry in existence to supply the required raw material or finished components. So the innovative design for the airplane could not be brought to fruition until a complete new industry was created to produce the raw material for the new design! It was an ambitious undertaking by any standard.

THE ORGANIZATION AS MORE THAN THE SUM OF ITS PARTS

According to the systems view of the organization, any complex organization is more than just the sum of its parts. Every complex system is defined not by the parts, but by the diverse and prolific interrelationships among all the elements in that system. Because the elements—the parts—do not function independently, it’s necessary to manage them together, as an integrated whole. We may not be able to create an entire industry to support our innovations, but we can identify the important capabilities wherein innovation could produce immense benefit.

TEN KEY AREAS OF

INNOVATION OPPORTUNITY

THERE ARE TEN specific areas where innovation can produce huge results. Each is but one of the interrelated elements in our system. Certainly, we can innovate in any one area, but when we do, our innovation will invariably impact other areas as well. When we anticipate these interrelated needs, we can prepare more effectively. The ten areas, shown in Figure 6-1, are:

1.Management development

2.Strategy development

3.Employee development

4.Product and service development

5.Process development

6.Tool and technology development

7.Supplier development

8.Market development

FIGURE 6-1.TEN AREAS OF INNOVATION OPPORTUNITY.

10.Brand development

These are primary areas of opportunity for the successful and vibrant organization. For an organization aspiring to innovation, each represents key capabilities wherein unusual skills may produce profitable innovations. These are also areas in which innovation can make a substantial difference in overall success.

CORE AND DISTINCTIVE COMPETENCIES

Every organization should be at least competent in all areas of their business, but core competencies—those fundamental skills that the organization does particularly well—are usually found in only two or three areas at most. Distinctive competencies—those competencies that the organization does uniquely well, and that competitors do not do well—are usually found only in a single area. Distinctive competencies are much less common and can create sustainable competitive advantage.

Core and distinctive competencies are not necessarily innovations per se. Competencies are the skills, systems, and values that sustain the success of your organization, though one would expect the rate of innovation to be highest in areas of particular competency. But innovation is not, and should not, be limited to areas of particular competency in a healthy and vibrant organization.

FOUNDATION ELEMENTS

If any of the ten areas listed above can provide a forum for major innovations, what do we mean when we say that every organization should develop the “capacity for innovation” in these areas? To be capable of innovating, several foundation elements must be present. At a minimum, these include:

•Understanding

•Experience

•Diversity

•Information and data

•Skills

To consistently innovate in a particular area—for example, market development—the person (or team) innovating requires some degree of each foundation element listed above. The person needs to understand the various elements of the market being targeted, and she must draw on experiences she’s had in this or analogous segments to form relevant conclusions. This allows her to formulate an idea for tapping the market opportunity and generating a concept. Information (including experience) about the markets in consideration is drawn upon to refine ideas and approaches. The more diverse and rich this information base is, the better the result. Specific skills are of course necessary to bring the innovation to fruition and hone concepts of pragmatic solutions to real-world problems. These skills might include marketing planning, statistical analysis, selling skills, customer research, sales organization, promotion programs, and financial analysis.

EXAMINING THE KEY AREAS

OF INNOVATION OPPORTUNITY

HOW ABOUT YOUR company? Have you developed the capacity to innovate in each of these areas? Are you capable of innovating in the ten areas of opportunity? Let’s examine each of the ten areas of innovation opportunity.

MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT

Managers often consider the development of their employees—or the lack thereof. They’re less likely to examine their own developmental needs and proactively take the steps to stay at the forefront of their profession. Yet what could be more important? As has been previously stated, no group of people has a greater impact on an organization’s success than management, particularly senior management.

As senior managers, do we understand the issues that underlie the process of innovation? Do we feel comfortable that we can create the environment and policies to encourage the innovative forces of the organization to their highest levels? If not, it’s time to crack the books and do our own research. We may need to study to find out. The Bibliography at the end of this book is a good place to start.

STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT

Successful strategies are arguably the central indicator of superior management. Strategy provides the fundamental basis for the innovations that make the company a superior competitor.

Everyone learns in grade school that Thomas Edison invented the light bulb. Fewer people know that Edison also started the electric power industry. Before a majority of homes could be connected by wire to a reliable source of power, innovation after innovation would be necessary. Edison needed a strategy to bring his business vision to reality.

He chose a strategy based on the technology of direct current (DC) power. His logic was that DC power was safer than alternating current (AC), operating at lower voltages, and besides, he had based all his experiments on DC. But DC ultimately did not prevail as the dominant technology.

Meanwhile, George Westinghouse had other ideas. In Europe, several successful AC systems had been developed. Westinghouse bought the patents of Nikola Tesla and hired him to make improvements to work better with Westinghouse’s AC power transformer. Despite attacks from the DC advocates, Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company was retained in 1893 to light the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In addition, the Niagara Falls were developed with Westinghouse’s AC generators. DC supporters were less successful in finding customers for their system.

Ultimately, it was alternating current that won in the marketplace. AC proved much more transportable, simpler, and more convenient. In actuality, it was also safer since it did not rely on batteries, which were a nuisance and could produce explosive hydrogen gas if the bank of batteries was not carefully tended. So in the end, the strategy based on DC power was a failure. No amount of innovation could overcome the inherent limitations of an inferior strategy. The same is true today.

EMPLOYEE DEVELOPMENT

Developing employees’ skills, knowledge, and experience is a central theme in the topics to follow. Employees are by far the most crucial element in our “system.” The interrelationships that form the network of the organization are primarily employee relationships. In addition, the experiences are employee experiences, the intellects are employee intellects, and the skills are employee skills. When the employees can’t do the task, it doesn’t get done. When we fail to invest in the people, ultimately we fail.

As with management development, employee development provides the richness of education, experience, understanding, and skills that permit day-to-day operations to proceed with superior efficiency and produce the commercially relevant innovations necessary for future success. A learning organization is capable of continually recreating itself as conditions dictate. The ability to recreate itself (what some have called reinvent itself) is the ultimate organizational creative act.

Without an active employee development program, the company is forced to try to recruit, hire, and retain the skills it needs. If the organization is small or growing rapidly, this approach can work pretty well for a while—maybe quite a while. Eventually, though, it catches up with those who try to cut corners this way. At some point, employees who lack the needed skills must be discharged and replaced with fresh employees with the new skills. The long-term impact on morale and loyalty isn’t hard to imagine when an organization is seen as one that voraciously ingests people and then just sends them packing like so much excess baggage.

PRODUCT AND SERVICE DEVELOPMENT

Products and services are the lifeblood of every organization. Few businesspeople would argue that score. One would presume, then, that all well-managed organizations place great store by the capability to produce an uninterrupted stream of new and profitable products and services that meet understood needs of a well-defined customer universe. Many organizations, indeed, try to act in precisely such a manner. Others, though, find successful products to be elusive. Frequently, a big product success presages several mediocre performers—and maybe some outright failures. This is tolerable, maybe, if the successes are big enough, but it is erratic at best. Any organization, with a little work and discipline, can do better.

Certainly, developing products and services (or at least acquiring them) should be a core competency of every organization. There are three key elements that make up this competency:

1.Strategic market understanding

2.Strategic product direction (superior strategies)

3.A repeatable development process

We can examine each element in the context of the Innovation Management Model (first introduced in Chapter 3). Such analysis shows that both understanding the market and having a repeatable development process are System II functions—that is, those that involve shared resources. These are shared systems owned by the organization as a whole and used by multiple System I (operational) teams. The strategic product direction is a System IV function (concentrating on future direction), and clearly within the System IV responsibility of senior management.

This means that market knowledge (or creation of a strategic market segmentation model, if it takes that form) is the property of the entire organization. Often, market knowledge is seen as the property of the marketing department, and hence neither trusted nor supported by other functions, often including management. On the contrary, it can only perform to potential if it is clearly and unquestionably shared corporate property, just like the company values or the headquarters office building. The market segmentation model is a valuable corporate asset.

Thus, according to the Innovation Management Model, the corporate strategic market segmentation model (the official view of the market) is managed as a System II (shared) resource. The strategic market segmentation model should be managed as a multidisciplinary asset, and hence by a multidisciplinary team or function. It may be necessary to develop this multidisciplinary resource, gradually weaning the model away from the marketing department to become the joint owned asset it should be. If you currently have no market segmentation model, creating one can be a powerful growth experience for key people resources in the organization.

Here are some guidelines for developing products and services:

•If you do not have a clear, workable market segmentation model, create one.

•Recognize that when top management is engaged in the product/service development project, it will be an important element of the strategic plan.

•Understand what support the product development teams need from the System II functions, and see that it is provided efficiently.

•Audit these needs occasionally to be sure System II functions are still performing.

•Formalize the development process to the extent that it is repeatable, or better yet, until the results are repeatable. Then stop formalizing it. When it becomes a bureaucracy, it is no longer working.

More frequently, we are seeing retailers—catalog, online, and brick-and-mortar—increasing their involvement in the product development process. They may not actually make the product, but they apply their customer knowledge and promotional expertise to specify products to be built to suit a specific target market. What else is product development? Sears had long been deeply involved in the product development business, but not in the manufacturing business. Lands’ End is another example. Many of today’s computer companies do more “developing” than they do manufacturing.

PROCESS DEVELOPMENT

Process development is similar to product development in many respects, but it is different insofar that it tends to be more internally and more functionally focused. Process is the sovereign realm of the operational manager. It is less about what and more about how than product development.

How we see the processes involved has a great deal to do with how they can be optimized. For example, when we only envision key processes according to traditional definitions and labels, we will, not surprisingly, arrive at the same justification for the process that created it in the first place. Not much room for innovation in that approach. It’s much more productive to experiment with different ways to “see” the processes by which the organization fulfills its purpose. An example is provided in Chapter 7 that demonstrates how a bricks-and-mortar manufacturer might reorganize by process rather than function. The key element in creating a structure such as this is the ability to envision the processes that will govern the structure and see them in the most useful way.

On a more specific and tactical level, process projects may be most effective when they are closely linked to product projects, because generally both can find significant improvements in the work of the other. There are often synergies, and huge benefits may be enjoyed when the communication and relationship between the process projects and product projects is close, cordial, and flexible. For example, a new product project to create a high-quality, low-cost lawn and garden tractor would certainly benefit greatly from a parallel project to streamline and consolidate procurement processes. Product and process are interdependent.

Here are some guidelines on process development:

•Develop interdisciplinary skills and relationships by rotating assignments.

•Avoid presuming that your existing, formal communications vehicles will be sufficient to clearly communicate between product and process projects.

•Process teams require shared resources as well as product teams. Make sure that they have them.

Process development is where systems thinking really shines. Process is about the interrelationships that make up the net of interactivity that constitutes the organization—the system.

TOOL AND TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT

We encounter tools and technologies at various points in the development of most products. Often, success or failure of a project depends ultimately on the availability of tooling and technology. Profitability may be possible only under an assumption that proper tooling can be developed. In the example of the SR-71 aircraft given earlier in this chapter, an entire manufacturing industry (a micro-industry, at least) had to be created to build a few airplanes. Most products are much less demanding, but the tools and technologies are no less important.

There are key junctures where tool and technology development is critical. Several are listed below:

•TO CONCEIVE THE PRODUCT. In the 1980s, CAD (computer-aided design) equipment emerged to design products using a graphic computer program. It wasn’t too long before someone developed the first CAM (computer-aided manufacturing) software to automatically write the necessary machining software for CNC (computer numeric control) lathes, milling machines, routers, and the like.

•TO PRODUCE THE PRODUCT. Steelcase, Inc., designed the largest selling office chair in history with its Sensor chair line. The chair was patented, of course, but the real profitability and competitive protection came from the expensive and proprietary tooling used to smoothly fit and glue the fabric to a molded foam substructure. Without the special tooling innovations, created in-house, cheap copies of the Sensor chair would have been on the market within a few months.

•TO DEVELOP THE PRODUCT. After the close of World War II, there was a great demand for office furniture to supply workplaces for all those returning from the war. During the 1950s and through the 1960s, several manufacturers developed procedures for testing the durability of key components of desks and chairs. Today, it’s taken for granted that wear-related components are tested for reliability prior to introduction (at least the quality ones are). There are now industrywide standards that have evolved from these early innovative testing procedures and equipment.

•TO DELIVER THE PRODUCT. Arriba and Commerce One are among the most powerful entrants in the fast-moving (and hazardous) world of business-to-business Internet technology. Suppliers and customers are being linked together electronically to conduct much of the business formerly done less efficiently by manual means. How this will ultimately be achieved, and who the prime mover will be, is yet to be seen. But change is certainly afoot.

•TO SERVICE THE PRODUCT. It’s difficult today to deal with a bank without being confronted with its automated phone service system. Such systems now deliver information on your balance, transactions, and general service through the push-button phone. When taken too far or less than brilliantly conceived, such systems can also be extremely frustrating.

•TO RECYCLE THE PRODUCT. A considerable little industry that remanufactures and upgrades used computers has sprung up to extend the life of rapidly outdated personal computers. As the rate of improvement in new equipment continues to increase, we may expect to see more of this activity. In another case, the office furniture market some years ago was flooded with used parts and pieces of the then–relatively new “systems furniture” (mostly panel systems). Methods, tools, and complete companies sprang up in the early 1980s to take these relatively useless and banged-up parts and pieces, refurbish them, and remarket them again as complete office solutions.

•TO RESELL THE PRODUCT. Since books have existed, there has probably always been a used book industry, but with the advent of the Internet, companies like Alibris.com, Bibliofind.com, and Amazon.com have placed the ultimate used book inventory at the fingertips of every potential buyer.

SUPPLIER DEVELOPMENT

The Toyota production system is the quintessential model of supplier development. In its march to become more efficient, the company chose to focus efforts on smoothing work flow. Toyota found that waste created uncertainty, and uncertainty—that enough good parts would be forthcoming, for example—caused function after function to create buffers, surplus inventory, etc., to bolster confidence they would not run out. Smoothing work flow called for eliminating these buffers and the uncertainty that caused them. Toyota was drawn to the idea now known as JIT (just-in-time), which caused a fundamental revolution in the relationship between the manufacturer and the supplier. To eliminate inventory buffers, it was necessary for the supplier to provide parts as needed with a great degree of certainty.

This caused manufacturers to concentrate purchases in the hands of a limited number of carefully selected, high-quality suppliers in which confidence could be vested. Reduction in the number of suppliers was followed by much closer engineering and development relationships with these suppliers. A cooperative, closely interrelated relationship with the supplier was in the interest of the manufacturer. The role shifted from one that was adversarial to one that was cooperative and system-enhancing, wherein both parties were seen as part of the same system. The system is now common throughout the developed world.

Initially, U.S. manufacturers tried to achieve efficiencies and lower prices simply by making strong demands on their suppliers. They later learned from Toyota that it was also necessary to help suppliers to become innovators on behalf of the manufacturer.

MARKET DEVELOPMENT

Market development should take place throughout the company, not just in the marketing department and sales department. Market development takes place in three distinct arenas:

1.Developing existing domestic markets

2.Expanding into new domestic markets

3.Developing or expanding foreign markets

In our view, the key to market development begins with a strategic market segmentation model. Once available, the detailed segmentation information is used first to examine domestic markets and analyze the product/service fit to currently served segments. Second, the segmentation information provides insight into the requirements of new domestic markets that are not currently being served by your company. For new markets, an opportunity analysis ensues from potential opportunities in new domestic target markets. In either case, innovation springs best, and with a greater sense of purpose, from accurate information about the various segments available to choose from.

Foreign markets almost always require a new segmentation model for each country being considered, but the principles of how to approach the opportunity are essentially the same as for domestic markets. The strategies may be quite different.

Access to markets (customers) is the principal governor of the engine of innovation. The most innovative organizations, particularly in the area of new products, are generally most hampered by an inability to reach the proper markets for their new products. If they cannot expand into new market sectors, then they are constrained to those they serve now, and by definition any new product or service outside that market is useless and a waste of resources. Thus, the organizations need to be able to stretch into new market opportunities. The key questions are to what degree they should enter such new markets, and how often.

If the organization is planning significant growth, the source of that growth becomes central. What will be required to provide access to the customers needed to meet the plan? Do you have the capacity for developing new markets?

DISTRIBUTION DEVELOPMENT

For some service organizations like hospitals, the product (health care) and the distribution of service are provided by the same organization at the same location. There is no distributor per se. The same may be true for other professions like law and public accounting. But for manufacturers of tangible products, all manner of distribution choices come into play. Where distributors and retailers are necessary to reach and serve customers, distribution choices are critical to success.

Distributors and producers usually interface on multiple levels. For instance, a manufacturer of office supplies may interface with its various distributors:

•At the sale level

•At the service level

•In customer service

•At the design-engineering level on build-to-order items

•At the relationship level (e.g., personal friendships and contacts)

•At the technology level (shared systems)

•At a coordinated product development level

In any event, the challenge of developing, expanding, and managing distributors quickly becomes a sizable chore in all but the smallest companies. Henry Ford is most often touted for his innovation of the assembly line and his unprecedented daily wage of $5. He is less often acknowledged for creating a distribution system capable of matching his fast-moving assembly lines. Without an innovative approach to selling his cars and getting them to their new owners, his other innovations would have been much less significant. Again, multiple innovations in several simultaneous categories are the norm rather than the exception.

BRAND DEVELOPMENT

When we drive down the street and see the “Golden Arches,” we immediately think of hamburgers, fries, and a shake. McDonald’s took an existing idea (fast food) and through its brand identification created the expectation of consistency. It was, as much as anything, this reliable expectation that the food in every McDonald’s would be equally good, and essentially the same, that made McDonald’s the best-known name in fast food the world over. (It’s become such a powerful brand, in fact, that it frequently becomes a surrogate for protests against so-called “American imperialism” in numerous foreign countries.)

Innovations in branding are so common that we usually overlook the potential for innovation available through brand creation and management. Andersen Consulting has now become Accenture, a deliberately nonoffensive word in any language. Without doubt, Andersen spent a great deal of time and money delivering just the right name—one that meant nothing, but implied a positive image.

DEVELOPING CAPABILITY WITHIN

THE INNOVATION MANAGEMENT MODEL

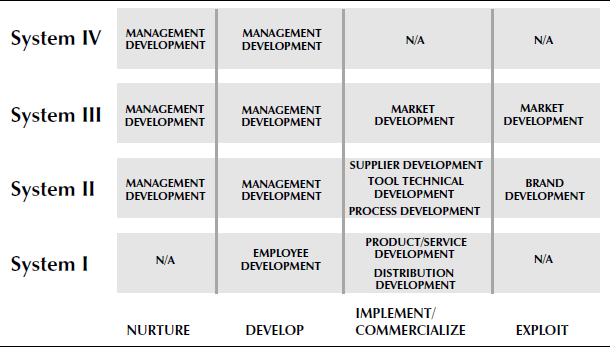

INNOVATIONS IN ANY of the ten areas of opportunity may be either strategic or tactical, but more likely there will be a pattern something like that shown in Figure 6-2. The roles and responsibilities of System I, II, III, and IV in developing the capacity for innovation are apparent from the figure. Please keep in mind that only the ten innovation development areas are shown on the diagram. Figure 6-2 is not a complete job description for each system level.

For example, System I (the operational team level) is primarily involved with employee development (their own), product and service development, and distribution development. System II (shared resources) is involved with management development, supplier development, tool and technology development, process development, and brand development. System III (the strategic and managerial level) is involved with management development and market development, while System IV (the future) concentrates on management development.

All ten of the areas in which we see opportunity for increasing the capacity to innovate fit easily on the Innovation Management Model. One observation may come to mind, though: Out of all ten opportunity areas, only two are placed under the activity cluster of “develop capacity.” This is not the paradox it first appears. It is because management and employee development tend also to encompass the others in the sense that the real capabilities of an organization are always in the heads of its people. To acknowledge this reality and also make the figure more meaningful, we allowed the other eight areas to migrate to those systems where they are more commonly found in practice. While the lines between cells on the figure are hardly rigid, we assign market development, for example, as a System III–level responsibility in the activity clusters of “implement/commercialize” and “exploit.” Our reasoning is that the decision responsibility for developing new markets is invariably higher than System I or System II. In other words, the capacity to innovate in the area of market development requires increasing the skills and knowledge of some pretty senior managers.

FIGURE 6-2.USING THE INNOVATION MANAGEMENT MODEL TO DEVELOP OR IMPROVE THE CAPACITY FOR INNOVATION.

Using the model helps us know what to manage, who needs to manage it, and something about what needs to be done to increase the capacity to innovate. We will expand on these ideas more as we move to Chapter 7.

SUMMARY

•Creating the capability for innovation is a management responsibility.

•Frequently, innovation must be achieved in multiple areas simultaneously to achieve sustained competitive advantage. Innovation in a single area is not sustainable.

•There are ten key areas of opportunity for strategic and tactical innovation: (1) management development, (2) strategy development, (3) employee development, (4) product and service development, (5) process development, (6) tool and technology development, (7) supplier development, (8) market development, (9) distribution development, and (10) brand development.

•Creating capability for innovation requires developing: (1) understanding, (2) experience, (3) diversity, (4) information and data, and (5) skills.

•The Innovation Management Model helps organize and assign responsibility for increasing our capacity to innovate.

NOTE

1. Jonathan Swift, Gulliver’s Travels (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998). First published as Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, by Lemuel Gulliver, in 1726.