![]()

TEN

Aligning Leadership

Role Modeling, Reinforcement, Reputation

WHAT WE EXPECT OF LEADERS

A couple months ago, on a plane waiting to take off from London to New York, the passenger next to me introduced herself. Her name was Rosemary. She sold electrical parts and was headed to New Jersey to meet with a perspective supplier. She asked what I did, and I told her. “I know plenty of people who could use your help,” she laughed. “I get that a lot,” I told her. “Most people know someone they think should be talking to me—usually their boss.” After a brief pause, she leaned over and quietly said, “He drives me crazy—absolutely crazy.” “Really? How?,” I asked. “Well, for starters, he can never make his mind up about anything. Everything is always last minute. The world and the industry is changing around us, yet he's not doing anything about it. He has no direction. I don't know what he's thinking. I don't think he's thinking at all. It's scary. It's really scary. I'm not sure what to do about it. I've been thinking a lot about it. I'm thinking about looking for another job, but at my age, and as a woman in my industry, it's not easy.”

“Have you talked to him about it?,” I asked. Rosemary shook her head. “It may be a good start. You may get answers to some of your questions.”

After a long pause, she said, “I don't think I can do that. He's likely to tell me something I don't want to hear.”

Leaders influence people's emotions. Sometimes they do it without even realizing it. Great leaders are those who are aware and conscious of their influence. They encourage people to deeply connect to what is most meaningful in their lives and bring it into being. The really great ones influence people to be themselves, to pursue their dreams and possibilities, and to be their best at everything they do, although on the surface it may not seem that way.

I've worked with leaders for quite some time and, like the rest of us, experienced leadership all my life. They have all influenced the way we see ourselves and our resulting decisions and actions. Some have influenced us more than others, leaving lasting impressions and, in some instances, changed the course of our lives.

Sometimes leaders influence and lead with intention, consciously engaging others. Others do it unconsciously, unintentionally influencing and swaying us. Rosemary's boss was probably unaware that his influence was affecting her emotions and making her anxious and worried about the future and less confident in him as a leader.

The role of the leader is very powerful. As a result, it is important for leaders to always pay attention to their actions. One wonders, does the CEO of Rosemary's company have a vision and strategy for the future? Is he communicating well enough and in a manner that deserves the commitment and engagement of his employees? Do they trust in his abilities? Do they trust him to be truthful with them? Do they trust enough in their relationships to engage in an honest conversation with him? Rosemary is too fearful to have an open and honest dialogue with him. There is an incredible level of interest and a significant body of work devoted to the topic of leadership and how and why leadership works. This information is important and provides great insight into the nature of leaders and those who follow them. When the influence of leadership scales, it is amazing. I am often surprised that a large group of people will consciously choose to give up its decision-making power. When it does, however, members expect a benefit in return.

I've concluded that we expect three things of great leaders: to create change, pursue truth, and know themselves. As the result of doing these well, leaders influence people to deeply connect to what is most meaningful to their lives and bring it into being. They influence others to live life to their fullest capability.

It's hard for leaders to accomplish any of the three without accomplishing the other two. Some examples of their interdependence follow. To create change one must know the current reality and the truth (often referred to as clarity) about what one is trying to achieve. If a leader does not know how he responds to change, it's difficult to create it. Without knowing himself, it's hard to step into a conflict to seek the truth. To influence others to change, leaders have to know their own truth.

WHAT DOES THIS HAVE TO DO WITH BUSINESS?

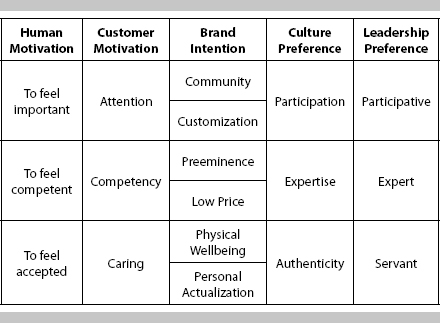

So far, we've explored human motivation and how our needs translate into and align to the three customer motivations; the six brand intentions, connecting the “what” and the “why”; and the ways products or services are strategically branded and sold. We also explored the three preferences of culture and the richness and power of how we work with one another, using the Business Code as the framework to understand the importance of alignment to any company or team. Now, we will examine the fourth element of alignment, leadership.

Most often leaders establish cultures based on their perceptions of how things ought to be. Very often, the cultures of companies and teams take on the traits and characteristics of their leaders, and we can often observe that the preferences of the culture are in alignment to the preferences—the style—of the leader.

At the most basic level, leaders influence culture in three ways; I call them the three Rs. They are role modeling, reinforcement, and reputation. The following equation is an easy way to remember them and see how they come together:

Role Modeling + Reinforcement = Reputation

In a company or team, leaders are the role models for how people are expected to work with one another to create success. Through their behavior, leaders provide the context for what is appropriate and inappropriate and what is acceptable and unacceptable behavior. In practice, this means it is not what you say that matters most; it is what you do. Actions speak louder than words. If a leader's actions and behavior are misaligned, how can they expect their followers not to be? This alignment of the leader is the seed of personal responsibility and how expectations are eventually met. Responsibility means keeping commitments. Accountability is how we measure the degree to which we are responsible, consistent, and forthright in keeping our promises. If the leader is not responsible or accountable, people's expectations will not be met.

Leaders are also responsible for reinforcing what behavior is acceptable and unacceptable and how people are intended to act toward and work with one another. This requires the leader to be actively engaged. Leaders reinforce behavior and how things are done in two distinct ways: active reinforcement and passive reinforcement. The first occurs when a leader is able to recognize what creates success in the culture and actively engages in reinforcing that behavior. For example, the leader sees someone, or a group of people, acting in the manner that is wanted in the culture, and actively reinforces it by talking about it, complimenting it, or rewarding the behavior and its outcomes.

The other side of active reinforcement is recognizing and confronting negative behavior and actions. This is creating change by expressing the truth. I define “confront” as stepping into the truth. To seek the truth, one has to be willing to step into the situation and the conversation. Thus, active reinforcement of what is unacceptable requires the leader to consistently confront it.

Often, leaders reinforce passively, thereby missing the opportunity to positively reinforce what is expected and failing to confront what is unacceptable in which case the leader silently gives permission to and reinforces the negative behavior.

The sum of role modeling and reinforcement is the reputation of the leader, which provides insight into whether he or she is truly aligned. Whether one is running a small local business or leading a large multinational enterprise, it is hard to imagine that the reputation of the leader does not influence and resemble the reputation of the business. Reputation influences a company's culture, as well as the customer's perception. Steve Jobs's reputation as the CEO of Apple is a great example. So powerful was the connection between his reputation and the company's that customers felt a kinship to him and believed that his personality was embedded in the innovation and quality of the products he oversaw. His reputation was so synonymous with Apple that the company's shareholder value was questioned and its culture cast in doubt when he died. This is clear evidence of how leadership is intimately and powerfully tied to culture.

Leaders build a number of paradigms about what a culture should be, including its core values, perceptions, concepts, and the resulting practices shared throughout the company. Leaders influence teams based on how they perceive the business environment and what it takes to succeed. Very often how groups and individual align to the pursuit of market and customer strategies are the direct reflection of how the leader thinks and feels about them. It's easy to see how leadership behavior misaligned to strategy may cause members to behave in a manner that does not support the brand intention of shared purpose.

Leadership influences the organization's and team's structure, how teaming occurs within, and across, workgroups. It also role models how company and team members communicate and how conflict is dealt within the culture. Leadership behavior misaligned to culture quickly results in distrust and lack of commitment among organization and team members, eventually negatively affecting performance. Among the most negative results are the shutting down of communication and the lack of information sharing, both of which occur when people fear the consequences of speaking up. Thus, the leader's issues become the company's issues.

The alignment of leadership behavior to the culture is essential. To better understand this, consider how human motivation that manifests itself through our behaviors influences how leaders think and act and how they influence others. What will quickly become apparent is leaders demonstrate a preference toward one of three leadership preferences and approaches—the one that reflects their individual personality and psychological makeup. This personal preference then becomes visible in the culture and, with few exceptions, a culture eventually develops and relies on a readily recognizable preference for the leadership that best aligns to it.

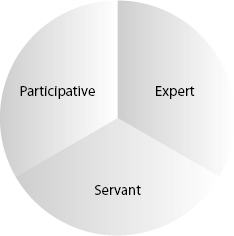

The three preferences of leadership are participative, expert, and servant. While leaders will at various times demonstrate qualities and characteristics of all three, their leadership approach provides consistency in their role modeling and reputation and a sense of reliability and predictability that others come to expect and that the culture will respond to in an aligned manner.

Through their preferences, leaders present patterns for how they communicate, make decisions, manage conflict, engage in competition, challenge others, run meetings, interface with customers, and manage risk. This is key to understanding why the behavior of the leader is often the greatest influence on the culture of the organization. When leadership at the top and throughout an organization is misaligned, it quickly results in confusion, a lack of predictability and trust, and dysfunctional conflict, all of which ultimately impact performance.

One of the most powerful aspects and opportunities of leadership development is enhancing self-knowledge and teaching leaders to choose the behavior that aligns with, role models, and reinforces the culture. Such power translates into consistency in the wide array of behaviors that people in organizations engage in, both individually and collectively, resulting in the consistent delivery of intention to the customer and the development and effective leadership of a well-aligned and high-performing culture.

One of the more powerful observations stemming from the application of aligned leadership is that a leader's orientation is also a reliable indicator of why individual leaders prefer a specific brand intention and how they pursue advancement and innovation. It also explains why partners and multiple leaders within an organization or team have differing views on the wide range of possibilities that relate to the basic what, why, and how of the business.

Individual preferences are what most often keeps executive and leadership teams from truly aligning. Frequently, the lack of a group's individual and collective self-knowledge interferes with team members coming together to agree on strategy, direction, and culture. When we pull back the layers and unfold the relationships, the emotions behind the challenges and issues inevitably get in the way of success.

THE THREE PREFERENCES OF LEADERS

There are many ways to define the approaches and patterns of leadership. Most have great commonalities. I find defining leadership style through an individual's preference is consistent with how we actually choose our behavior and with the approach to alignment the Business Code offers.

The idea that leaders are better when they have self-knowledge is not new. Understanding your preference as a leader gives you knowledge about your behaviors and central tendencies and about how you influence others to take action. Understanding your behavior provides you with powerful insights. For one, you'll be better able to acknowledge your emotions and feelings. You'll gain an increased awareness of their origin in your own self-concept in relationship to the world. Your self-concept includes how you see yourself emotionally, physically, socially, and spiritually, as well as what your psychological needs and preferences are for importance, competency, and acceptance.

The result of our emotion and feelings are our behaviors. Self-knowledge about our behavior, what we do and say at any particular moment, allows us to connect our behavior though our emotions to what we seek from others. We all have the power of choice. We can choose what we do and what we say to influence others. As a leader with the power of choice you can be flexible in selecting the behavior that will best serve the relationship and your desired outcome.

It is important to remember that:

- There is no single preference or style of leadership behavior that is successful in all situations.

- While you possess a preference and orientation to your approach as a leader, you have the power to choose a specific set of behaviors in any given situation.

- Of the three primary styles of leadership, no one is better than the other two. Successful leaders are able to demonstrate leadership behaviors that reflect the environment or culture they are leading.

- Your leadership preference reflects the way you prefer to lead and describes “how” you and others see your general approach, as well as behaviors you choose specific to the different actions you undertake as a leader. Some behaviors and actions are directly related to your leadership and contribute to your overall make-up as a leader. It is important to consider the specific elements of leadership that you may apply in different situations.

- Your overall leadership behavior is not completely defined by your preference; it is a unique combination of behaviors and leadership characteristics associated with all three preferences and your unique make-up. Understanding this allows you to develop and benefit from your ability to use self-knowledge to make wise choices about how you lead and influence others.

THE PARTICIPATIVE LEADER

Mark Aardsma, the founder and CEO of ATS Acoustics, is an example of a participative leader. He told me that he had moved his office to the second floor of his company's building. This separated him somewhat from his team members. From all appearances, Mark likes to be engaged with and spend time with people. He strives to be engaged with his employees and build relationships. Historically, he has spent a good deal of time close to the company's operations. While he is very capable, has a high degree of business acumen, and possesses strong analytic skills, his passion for business is grounded in a desire to spend time working with and coaching people. His workspace had always been close to the employees he worked with.

I wasn't surprised that he wasn't sure if he liked the change because he really hadn't spent any time in his new office. Apparently, when he came into the building each morning, he immediately began engaging and working with the employees on the shop floor. Since I've known Mark, he has become increasingly aware of the value of directly coaching his employees. He finds it a wonderful way to increase their capabilities, and it has resulted in a higher level of delegation. Mark advocates teamwork among his employees and believes that the one unique thing his company delivers to its customers is an extraordinarily high level of customer service. He believes so strongly in being responsive that the company does not use an automated phone system—no recorded voice or set of prompts and choices—and it doesn't take more than a couple of rings for someone to answer a call. Mark's belief in the value of giving attention to the customer is unwavering.

Several weeks after the move to his new office, Mark told me that he liked having the space to do one-on-one coaching with employees and was holding meetings there. He even added more furniture and arranged his office to accommodate the meetings. The traits and characteristics of participative leadership are ground in inclusion and attention. The participative leader prefers high levels of team and group interaction that require team members to work closely together. This results in a high degree of communication, information sharing and social interaction. Often, participative leaders refer to their companies as one big family and create environments that motivate and encourage interaction. They enjoy the idea of community and feel that connection is a key to success.

Participative leaders are good team builders and facilitators of group environments, assuring that individual members of the group or team feel included, paid attention to, and listened to. If someone is not participating, the leader will intentionally invite the person to get engaged or ask for their comments. They further accomplish this by asking each person for input. Emotionally, the worst thing that can happen is for someone to feel left out.

Participative leaders show a preference for planning and strategizing that is group focused with a high level of involvement, broad participation, and often brainstorming. They emphasize diversity, shared problem solving, and often push for consensus, unanimous, and concordance-based decision making. When it comes to a company vision, mission, and strategy, they prefer to draw in the group to articulate it, which is also a way to ensure their involvement. They often rely on group members to do the more detailed work. Shared reward is often the preferred approach of participative leaders, and group outcomes are frequently treated as more important than individual accomplishments. At a company level, this often leads to profit sharing and group celebrations. For some participative leaders, the goal is to create an ESOP or employee stock owned company. Participative leaders often focus on finding win-win solutions and outcomes to conflict and frequently include all members of a team or group in the process.

At times, they will work to accommodate or include another person's point of view. The participative leader will often rely on building goodwill and trust in relationships, leveraging the power of relationships over the power derived from the use of granted authority or rank or individual expertise. Their key motivation is the desire to provide others with a sense of significance, self-worth, and inclusion.

Participative leaders naturally show a preference for product or service strategies that offer a high degree of attention to the customer and promote connection and community. The idea of spending time with customers is important, as is bringing customers together. Often, they gravitate toward partnerships, joint ventures, and sharing strategies and ideas, including the possibilities of cooperative competition.

Their potential weaknesses, challenges, and criticisms include a desire to engage in too many meetings, to invite too much collaboration resulting in too slow decision making, to fail to take a stand to confront difficult situations and conflict when necessary, and to overlook group dysfunction, preferring to overharmonize or maintain the status quo. They may not share negative information or confront lapses in individual responsibility, accountability, or team performance. They may also fail to create detailed and measurable goals in planning and strategies and not offer enough structure and clarity in defining measurable objectives and outcomes, often overlooking details and timelines.

At their best, they work to assure that a high level of teamwork, communication, and information sharing takes place. This extends itself outward and is not lost on the customer. Edgar Huber, the CEO of Lands’ End, once told me that an important aspect of his role is to build a bridge for communication across the company. That's a good description of a participative leader.

THE EXPERT LEADER

Rick Whipple is driven to achieve and accomplish the extraordinary. When something is mundane and without risk, he's looking for the next possibility. Throughout his life, and in his business, he pursues excellence. In his view, everything a person undertakes has challenges, or an element of something they don't like. Rick loves being in business and enjoys its intellectual aspects. He likes the challenge of finding new and better ways to do things, including how to lead his company. If he didn't, he'd probably be bored. To Rick, WhippleWood is much more than a business. It is a pursuit of possibilities, which is why he believes that while expertise and competency are the most important aspects of the company's capability, it's a matter of finding them in the right people. He competes in an industry that demands you be different to be better. He illustrates the expert leader.

There are approximately 35,000 CPA firms in the United States; approximately 500 are as large or larger than WhippleWood. They all hire really good people. Yet most don't get to be among the biggest and don't grow. Rick doesn't think those other companies are hiring the right people. Any firm, large or small, can get competent employees. For WhippleWood, it's about finding a certain type of individual.

In 2007, in the face of the coming recession, his firm took the risk of buying the building it currently occupies. In the heart of the recession, 2008, he began adding employees and continued growing the business. At that time, Rick recognized the need to bring aspects of teaming into the business. He didn't want the culture that is typically associated with accounting firms; he wanted it be unique and to buck the trend. He took his employees on a retreat and, building on its momentum, in four years, the firm doubled in size. As he sees it, the company's now annual retreats are critical to its success. He believes that when you determine the key aspects of the business and continue to focus on them, they become a part of your culture. The outcomes of the first retreat included WhippleWood's statement of purpose, the articulation of its values, and its business strategy, including designing the firm's structure, identifying its ideal customers, and strategizing how it would engage with clients.

They also established five “Champion Groups.” People choose what group to participate in and, if they want to, can switch. The groups allow employees to pursue individual interests and strengths. The individual groups focus on five pursuits:

- Great Work Environment.

- Our People (improving performance; it uses a balanced score card with five measurements).

- Standards, Processes, and Technology (improving the mechanics of the firm and how things get done, including data management, which is key to an accounting firm).

- Our Clients (developing relationships with clients including qualifying them, managing which clients they want and don't want). The firm turns away more clients than it accepts.

- Marketing and Business Development (community involvement, tracking the business pipeline, etc.).

The groups’ purpose is to provide unique elements that integrate participation into the company's culture of expertise and that allows employees to directly affect the company in positive ways. In Rick's view, people work at WhippleWood because they want to, not because it's a job. WhippleWood's employees work in an industry that, at certain times of the year, puts pressure on everyone. This makes its unique culture that much more important. WhippleWood employees are happy, focused, and hard working. They are also informal with one another. Monday mornings everyone gathers for a meeting, and they watch an inspirational or subject matter video. The person that chose the weekly video explains why, and everyone then shares something they found relevant or significant in their work and lives. People are very open in what they share, which they call “moments of happiness.”

These are all conscious elements that help integrate participation and authenticity into the company's expertise culture. They add uniqueness to a culture well aligned to WhippleWood's brand intention of preeminence, which has many of the trademark characteristics of an expertise culture. Employees are measured on how they build on their individual performance and set goals and outcomes going forward. These include metrics for the amount of work people do and how it is billed; client generation; self-improvement; and the reconciliation of what each does for the firm. Employees design their personal education and learning plans and their career paths.

Rick Whipple's influence on his company's culture is apparent. His goal is to rely on his influence more than his authority. Based on people's competency and capability, he likes delegating decision making. He is committed to leading a company that is dynamic, exciting, and fun. He also recognizes that he may have to push people harder to get to where they want to go and that they are ready to respond.

Rick believes that if you have the skills, you can go wherever you want to go. The single biggest challenge is getting the most competent people to lead his firm in the future. Regardless of how long they stay and where they eventually go, he wants employees to look back on their experience at WhippleWood and say, “That was great, I used to work there.”

Rick is an example of an expert leader who has a great sense of his own influence and wants to find the uniqueness in himself and his company. He also has the valuable capability to integrate aspects of the other leadership styles, which allows him to intentionally create a unique culture for his company.

Expert leaders typically prefer taking control of situations and dominating team environments, challenging team members to demonstrate individual competency and responsibility. They are seen as preferring organization, functional role definition, and a sense of hierarchy. Often, they try to influence team members’ ideas and are seen as persuasive, regularly using analytical approaches, factual data, and statistical evidence in demonstrating their point of view. In conflict, this often results in a win-lose approach.

Expert leaders typically take an analytical approach to planning. They are often considered visionaries. Characteristically, their visioning process relies on their analytical capability. When it comes to risk, they will either work from a place of knowing or affirming belief in the potential outcome outweighing the potential downside. Expert leaders see themselves as resilient and persistent in reaching their objective and goals.

Expert leaders naturally prefer meritocratic forms of reward and rarely show empathy for those making mistakes. In solving problems and making decisions, they typically rely on team members who offer the highest level of expertise and knowledge and will often engage individual experts from outside the team and organization. They often create competitive environments, looking for the “best and brightest” team members to “step up” and compete with one another. They are seen as challenging the status quo and being innovative, consistently seeking continuous improvements in processes and systems and better outcomes. The key motivation of expert leaders is their desire to appear competent and in control and to leverage their knowledge and expertise, as well as that of others.

Strategically and when engaging customers, expert leaders prefer to lead the way. Creating solutions and finding answers internally and externally is their specialty, whether it's solving problems or developing products or services. Expert leaders often convey a “we will build it and they will come” attitude and are seen as driven by innovation and futuristic ideals.

The potential weaknesses, challenges, and criticisms of expert leaders include the desire to overcontrol an environment, dictate the actions of others, and centralize decision making, as well as an inability to effectively delegate responsibilities, authority, and power. They often find solutions to problems and reach decisions faster than most people, which keeps them from gaining the opinions and insights of others. This may leave team members feeling unheard, ignored, and unrecognized for their competency and expertise. Members may feel that the leader is too strongly influencing their ideas, resulting in a future lack of input and healthy discourse.

Expert leaders can be seen as creating overly critical environments, often suggesting that the performance of others, despite their accomplishments, may not be good enough. This may result in others feeling a lack of recognition. While challenging others can have its benefits, expert leaders can easily fall into patterns of behavior associated with a “must win” attitude and appear to need to always be right. Because expert leaders commonly believe that improvement is always possible, they may create new and multiple strategies at a pace that leaves followers confused.

Expert leaders place a great deal of importance on finding the right people for the right job. This creates a reliance on not just hiring competent employees with expertise, it also requires a commitment to training and development. This also extends to the development of competent leadership.

Over the last decade, the story of the North American Division of Ensign Energy reads like a guide to leadership alignment. Since 2001, when its management team strategized its alignment, the organization's assets have multiplied over 250 times. By 2013, as a result of its drive to deliver new technologies, it has grown from a little over 100 employees to over 2,800.

The keys to its alignment include a clearly defined strategic path to providing superior technology and customer service, a well-articulated and aligned culture of expertise and competency, and consistent leadership. For most of the past decade, the division has been led by Tom Schledwitz, who espouses values centered on finding people who are the right fit for the culture, relentlessly investing in their training and building career paths. For Tom, it's all about the people. He wants leadership that is more about communicating the intention and the outcome than being prescriptive.

To him, success comes from hiring and training the right people who will develop the right programs and processes. Tom looks for people with an entrepreneurial flair who are more apt to want to contribute and make things happen. He advocates freedom over compliance, wanting people to express themselves rather than being reactive and working within a program. He believes that good leadership is about managing a process without micromanaging people or taking away their creativity and accountability. He believes a good leader has high integrity, which is a key focus of leadership in the division's culture, and looks for leaders who know the core values are and can consistently communicate them to others. Tom also believes that a good leader is aware of what he doesn't know; a bad leader is only aware of what he does know.

Tom Schledwitz is a great example of an expert leader focused on building people's expertise, competency, and know-how. Like Rick Whipple, Tom believes it's always about the right people. In addition, both want to be innovative and unique; to be challenged and to challenge others; and to help others develop, grow and be successful. Further, they want their employees to be responsible and to take action that best delivers to the customer. Last, they both have a great deal of influence on their respective cultures.

THE SERVANT LEADER

When Dr. Carl Clark became CEO of the Mental Health Center of Denver (MHCD) in 2000, the organization was unprofitable. It had struggled with the implementation of business disciplines and a lack of clarity in its mission and vision. While the Center was delivering services to those in need, it was struggling to find a consistent way to operate, put financial disciplines in place, clearly articulate its culture, and build the relationships necessary for sustainability and growth. Clark's approach is that of the servant leader.

In the past, the Center's problems had been smoothed over, and one of Carl's first challenges was to confront and begin addressing some of the more critical and longstanding issues. In particular, he had to find ways to better assess and measure the Center's performance, including its systems and processes, as well as its outcomes in helping those who were coming to MHCD for services. Before alignment, he needed employees to buy into in the effort. In an organization focused on creating individual empowerment, getting everyone moving in the same direction isn't easy.

Carl's first engaged the members of his board and leadership team in clearly defining the mission of the Center and then to articulate a strategy, one that would require significant change. When it comes to creating and leading change, it is often best to use what is already present in the culture to leverage the change it needs to create. Carl asked everyone—the board members, leadership team, and all the employees—to act in the best interest of those they served. He consistently communicated that the only way to help others was to first commit to helping the Center by undertaking the operational changes required. He focused on doing more of the good work the Center prided itself on; his priority was the care of consumers, and the only way to get there was to focus on implementing aligned operational capabilities, business disciplines, and a healthy culture. He engaged everyone in a vision that focused on the creation and implementation of cutting edge approaches to mental health care and that led to its clients living healthy, productive, and meaningful lives. This was a greater and more compelling vision than just providing care.

Carl engaged everyone in the conversation, including the community. He strove to include everyone in the conversation and worked tirelessly to work in service and dedication to the Center. The resulting mission of MHCD is enriching lives and minds by focusing on strengths and recovery. For servant leaders like Carl, the source of their power and influence is to role model and reinforce the idea of helping others to succeed by making them better. He recognized that everything coming together required an aligned culture. Therefore, part of the Center's mission was to create a wellness culture within the organization, establishing a work environment where people can do what they do best, be supported, and enjoy their work.

To assure that the Center had aligned leadership, Carl provided training and education to those in leadership roles. They underwent extensive development; each had individual long term goals and outcomes. The Center built a new facility and received the highest Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED®) Platinum Certification from the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC). It has received numerous awards for its recovery programs and for bringing mental health care into the national conversation. Carl has testified before Congress on behalf of mental health and, as one of the foremost recognized leaders in the field, has become a nationally recognized resource for its advancement. In the span of a decade, MHCD has become the model for other mental healthcare organizations.

For servant leaders, like Carl, the primary motivation is helping others. Over the last several decades, this preference has received greater recognition and attention. While servant leaders are often considered less competitive than others, it is not true. As with Carl Clark or John McKay of Whole Foods, they can be very competitive and achievement oriented, yet they, like participative and expert leaders, have a unique way of achieving their goals.

Servant leaders prefer empowering and enabling others and building commitment to the purpose, cause, or ideal. They are developers and nurturers of others. They are stewards of the people and organization. They typically derive their influence from their alignment to a set of values and beliefs that inspire people to create change. They are charismatic and pursue a high-level purpose and vision; they are seen as authentic and caring.

Servant leaders prefer less structure and measurement and are inclined to encourage others to define their own goals, motivating them through intrinsic rewards and opportunities for self-actualization and contribution. They often express the belief that mistakes and errors are an expected part of the learning process.

Servant leaders are often able to build close personal relationships and create warm, friendly environments. They are comfortable with the emotions and feelings of team members and followers. When confronting conflict, they are open to new ideas and diverse points of view. They prefer resolutions and outcomes that reflect “the right thing to do.” Their key motivation is to be liked, loved, and admired and to leverage the good intention of others.

Servant leaders show a strong tendency to pursue customer experiences that deliver wellbeing, personal growth, and forms of enrichment, which are natural extensions of their own curiosity and desire to grow and self-actualize. They are often described as generous and humanitarian people, who encourage others to pursue causes. Despite their unassuming demeanor, their charismatic energy often puts them at the center of their companies. Potential weaknesses, challenges, and criticisms of servant leaders are a lack of direction and their potential to underemphasize measurable outcomes and performance. Therefore, they are thought to focus more on intention than results, ignore concrete and objective data, and minimize the need for strategy and planning. They may be considered too optimistic, and their inspirational style can burn out team members. Because they desire to help others grow and succeed, they can easily overcommit and miss deadlines and, because they want to be liked and don't want to let others down, it is difficult for them to say “no.”

THE ALIGNMENT OF LEADERSHIP

An aligned leader's orientation is a reliable indicator of why individual leaders prefer specific brand intentions and how they pursue advancement and innovation. Understanding this benefits them and their groups.

Figure 10.1 illustrates how important leadership alignment is to the success of any company, as well as team leaders themselves. The level of success is a direct outcome of an individual's alignment to the company's market strategy. Thus, participative leaders generally succeed best in pursuit of the brand intentions of customization and community; experts in pursuit of low price and preeminence; and servants in the pursuit of physical wellbeing and personal actualization. For the same reasons, partners, leadership teams, boards of directors, and leaders within any organization or team can easily have differing views on the wide range of possibilities that relate to the basic what, why, and how of the business.

Figure 10.1 The Alignment of Leadership

WHEN LEADERS AREN'T ALIGNED

There are a variety of reasons why a leader may not be aligned to the cultures for which they are responsible, including poor succession planning, poor hiring practices, and a lack of clarity about the desired leadership approach. There are several approaches to this problem. The first is for the leader to assess the misalignment and choose behavior that allows integration into the existing culture. An expert leader, who realizes she is leading a participative group rather than making decisions on behalf of the team or getting the advice of one particular member, should hold meetings to reach consensus decisions. A servant leader in an expertise culture realizes that one of the company's better clients is not getting the level of service they expect. Typically, he would let his team know about the issue and expect someone to empower himself to resolve it. Instead, to better align to the culture, he goes to the individual responsible for that customer or, based on what the customer needs, goes to the person whose role it is, and asks that person to respond. He will also meet with the employee to discuss how to avoid a similar situation in the future.

For a leader, whose style and approach is misaligned to a culture, to successfully integrate requires the flexibility to choose behaviors that will create alignment as well as a high level of self-knowledge and a keen awareness of the range of potential situations they may have to confront. Many leaders have had success doing this by hard work and commitment.

The second approach occurs when a leader decides it is best to change the culture. Because this always has a significant effect on a company or team, the most effective and expedient approach is to replace people. An exception is when the company has a culture it aspires to, has already aligned several of the keys, and is working toward increased alignment. In that case, it is more about further aligning and improving an existing culture than about a complete change of preference.

The third approach occurs when a leader's preference differs from the culture's, and he is unwilling to align to it. He can try to influence a change in the company's culture, yet if, over time, the strategy fails and he still won't change his behavior and leadership style, he must leave, willingly or unwillingly.

The fourth option is to “get out of their own way.” For example, as part of the succession plan of a family business, the daughter of the founder, at his retirement, took over the company's day-to-day operations and leadership. Her father was a very outgoing participative leader who created a family-like culture. The daughter was a more reserved expert leader, who enjoyed the analytic nature of the business.

She quickly realized how misaligned and different her approach was from her father's. Rather than disrupt the business or take on the challenge and risk of changing her own approach, she turned over the day-to-day leadership to one of the managers whose style aligned to the existing culture. When she attended meetings, she was intentional and very conscientious about not taking over or interfering with the company's participative planning and decision making processes.

In addition to influencing a company's culture, leaders influence the strategic thinking process. In this last example, the daughter needed not only to be aware of her influence on the culture and how things were done, she also had to be aware of her influence on the strategy and the what and why of the company.