CHAPTER 12

The Gift of Learning

EDUCATION PLANNING

Ultimate Advice

Jason Stevens shares a revelation in The Ultimate Gift: “The desire and hunger for education is the key to real learning.”

Amy Skogstrom, managing editor at Automobile magazine said, “When someone asks me what car I’d buy if cost were no object, I pretty much always say the 911.” Ms. Skogstrom is referring to the Porsche 911, the iconic sports car to best all sports cars. I can remember, as a boy too young to even drive, having one of those hypothetical daydreams as I thumbed through a magazine of sports cars, picturing a wealthy philanthropist walking up to me and saying, “Hey kid, I’ll buy you any car in that magazine—the cost is no object.” In that recurring daydream, I too have always answered, “the 911.” There’s just something about it. But alas, when it comes to automobiles, cost is an issue, so I’ll not be parting with the $135,000 required to buy the 500 horsepower, 2011 Porsche 911 Turbo, which travels from zero to 60 miles per hour in just 3.5 seconds.

There are very few things in life for which we could actually say money is no object. The health and welfare of my family is the first that comes to mind. But even then, I confess that I certainly have allowed money into my decision-making process. I have, for instance, chosen a pediatrician who is in my health insurance network. Is there a better pediatrician who may offer a concierge medical service independent of insurance hassles? Possibly, but I haven’t explored those options because I know the cost is quite high. For most decisions in life, money may not be the primary driving force in our decision, but we delude ourselves if we claim that it is a forgotten nonfactor.

Ultimate Advice

You don’t have to go to college. This isn’t Russia. Is this Russia? This isn’t Russia.

Ty Webb, Chevy Chase’s character in Caddyshack

This is no more evident than in the realm of education. Does education have a price? As parents, do we owe our children a particular educational path? Is a college education an entitlement or a privilege? Before we jump headlong into this debate, let me clarify a few things. Learning has inherent value which is incalculable. Education is one of the primary ways we learn. I don’t, even for a second, want you to receive a message suggesting that education is overrated. I teach on the college level and believe that it is one of the more important things I do in life, but I don’t believe education is priceless.

Timeless Truth

Learning is a lifelong pursuit that costs you nothing more than a library card or Internet access. Education can be one of the most costly endeavors that you and your children may ever face. It’s critical that you keep this in perspective.

The great Warren Buffett often says, “People know the cost of everything and the value of nothing.”

In 1980, I was in college at a private university. The cost seemed staggering at that time and miniscule as I look back on it today in light of current tuition rates.

I met many lifelong friends during my college years. One night, we were sitting around the dormitory at approximately 3:00 a.m. pursuing some scholarly activity. I believe we were bouncing a golf ball off of the wall as we discussed the fact that none of us had any money. We didn’t even know anyone who had any money.

As the dialogue continued, we determined that if we ever got out of that institution—which was somewhat doubtful at that point—and if we ever had financial success in our lives—which was even more doubtful at that point—we would make it possible for talented and deserving students such as ourselves to receive scholarships to college.

Nine years later, we were all together again attending the wedding of one of my classmates. The night before the ceremony, we were sitting around a hotel room in the middle of the night discussing the good old days in college. Then someone remembered that long-ago commitment to do something for young people who wanted to go to college. That night, five of us started a private scholarship fund that, over the last 20 years, has provided 400 scholarships for students attending that private university.

The semiannual process of reviewing scholarship applications and the accompanying financial forms has made me uncomfortably aware of the staggering cost of a college education today. Twenty years ago, we occasionally saw a student leaving the university with eight or ten thousand dollars in student loan debt. At that time, student loans were at a ridiculously low interest rate and did not even begin accruing interest until after graduation. Today, it is not unusual to see a financial aid form on a scholarship application where a student has racked up six figures of student loan debt for an undergraduate degree with interest accruing while he or she is still in the university.

People make financial mistakes often because they weigh emotions too heavily in decision making. A college education for your children is one of the hardest areas to not make an emotionally charged decision, but it is critical for you and your child that you develop your education funding plan within the context of a sound financial plan.

Jim Stovall

This chapter is for students, prospective students, parents of students, grandparents of students, aunts and uncles of students, mentors of students . . . okay, just about everyone. We will regularly address parents, since this is a major concern of so many, but we fully recognize many students are on their own financially, and we have specific counsel for you as well. The bulk of this chapter’s content regards planning and saving for college expenses, not because there aren’t financial considerations to be made for preschool, elementary, and secondary education, but because the cost of college is large enough and far enough into the future (if you start early enough) that saving is a viable strategy.

The decisions you make about education for you and your children are informed by your Personal Principles and Goals, the topic of our discussion in Chapter 2 and indirectly throughout the book. Please reference those as we propose a framework to answer the whether and the why before you invest a dime saving for education. Before you can enter into an education savings plan, you should articulate your family education policy using the following three steps:

Step #1: Can I?

Can you afford to pay for your children’s college education? Some of the more interesting and inspiring people I have met are taxi cab and executive drivers in and around New York City. On most occasions, I hop in the car and exchange greetings and then say, “That doesn’t sound like a New York accent. Where are you from?” The answers are like the roll call of the United Nations. And I’ve never tired of listening to the answer of my typical second question, “What was it like to pick up and move to a place so different from your homeland?”

Just think of the courage it takes to do that. In several cases, it was a personal aspiration that brought someone to the States—a young, single person who thought America would offer unlimited opportunity. But many times, the answer has more to do with the hopes and dreams the drivers have for their children than themselves. They want to give them greater opportunity, and they’re working tirelessly to do so.

Many of them are working more than one job just to pay the rent, keep the lights on, and put food on the table. They have done everything imaginable to give their children the opportunity to go to college and succeed in the world, but they simply don’t have the money to pay their children’s way through higher education. Possibly their children will have the opportunity to provide that benefit for their grandchildren. It’s hard as a parent to face this question—Can I?—but you know the answer, and you and your children will be better served if you answer it honestly.

One of the more financially selfish things you could do is set aside your personal plan for financial independence in favor of paying for your children’s education.

You don’t have to be a first-generation American cab driver to qualify for “I can’t,” even if due to your own ignorance or negligence. If you analyze your financial posture and you’re not adequately funding your retirement or financial independence plan, you can’t afford to sacrifice that plan to fully fund your children’s college education. I know you have friends who’ve told their stories of financial martyrdom for the benefit of their children at cookouts and cocktail parties, but they’re not actually doing their children any favors. Here’s why: It’s easier to pay off a student loan than it is to bail out your parents when they’ve fallen short on cash in retirement.

Step #2: Will I?

Will you apply the resources you possess to pay for, or to help pay for, your children’s higher education expenses? Even if you can afford it, this is a personal decision, and just because a mutual fund commercial, your stock broker, or the manager at the bank implored that you should be paying (and saving in their investment vehicle of choice) for your children’s education doesn’t mean you should. It may even be a parenting strategy of yours to allow your kids to fully or partially feel the pain of paying for their own college education.

It is not my intent to strip you of a healthy desire to pay for your child’s education but to give you the freedom to recognize that it is a choice of yours. Remember to be impelled, not compelled, to find your own path in your financial endeavors.

Consider the example of Daniel and Sharon, a young couple with five children and a household income of nearly $1 million annually. Theirs is not old, but new, wealth, and they’ve made it their mission to ensure their children do not become apathetic to the financial realities of life due to their newfound affluence. Certainly, in answer to Step #1, they certainly can afford to pay for their children’s college educations. But they have strategically chosen to fund their children’s higher education pursuits with a creative strategy designed to teach the lessons Daniel and Sharon want their kids to learn.

Step #3: Articulate Your Family Education Policy

Whether your family is awaiting the birth of your first child or getting ready to send him or her off to college, consider crafting an education policy for your family. Daniel and Sharon decided their family education policy would be to fund two years of education for each of their children, but not the two you might expect.

They are putting the financial burden of college on their kids for the first two years. If their performance in those two years meets certain requirements, they’ll fund the second two years. If their kids want to go to an out-of-state university in Miami or San Diego so they can wear shorts and flip-flops to class year round, that’s no problem; but they’ll be the ones paying twice as much as they would for the comparable in-state university. If one of their children is showing signs of being more interested in partying than learning, the pleasure-seeking youth can do that on his or her own dime initially. If the grades are there, Mom and Dad will pick up the rest. Their family education policy is not antieducation; it’s prolearning.

Our family plan is pretty plain vanilla. Assuming our boys meet a couple of minimum requirements in their high school years, they’ll be supported financially for the equivalent cost of an in-state, state university. If they choose to go to an out-of-state, state university or a private college or university, they’ll be responsible for the balance. That could be made up by scholarships or loans for which they are responsible. I don’t want to limit them only to in-state, state universities, but that sets a benchmark for their financial support.

Your plan shouldn’t be mine or Daniel’s—it should be your plan. Use creativity to craft a plan that suits Mom, Dad, and your unique children. As we absolve those who may be driven by guilt to do something that isn’t consistent with their own Personal Principles and Goals, let me also clarify that there is nothing wrong with choosing to pay top dollar for your sons and daughters to go to an elite school. If you come from a long line of Harvard grads and you can’t imagine seeing your children in anything other than crimson, then that should be reflected in your family education policy. But before you commit, know what you’re getting into financially.

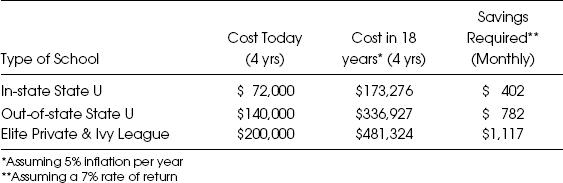

Today, the average cost of tuition, room, and board at an in-state, state university is about $18,000 per year. In order to go to an out-of-state, state university, you can reasonably expect the cost to nearly double to $35,000. The top private and Ivy League schools cost upwards to $50,000 per year. So, if you committed to sending your newborn to college and intended to save 100 percent of the total cost by the time the expense is borne, how much would you actually have to save each month from the day Junior is born? The answers are $400, $800 and $1,100, respectively as you’ll see in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1 The Cost of Saving

Am I telling you that if you wanted to save 100 percent of the expected cost of sending one child to Harvard you’d have to save $1,117 per month from the day that child was born until he or she started college? Yes. So if you had three children, all of whom you intended to send to Harvard, you’d need to save $3,351 per month? Yes. In fact, the assumptions I used in Table 12.1 were five percent for the inflation of college costs and seven percent for the earnings on your savings. Some estimates would suggest that the inflation expectation is too low and the rate of return too high (based on the last decade). So, can you afford to send your children to the school of their—or your—choice?

I don’t want to scare you to the point that you decide to give up on saving to send your kids to college. That would be a mistake. We haven’t even gotten to the education savings plan yet; we’re still working on the family education policy at this point. But these numbers speak volumes to support the notion that you must take your personal finances into account before you pledge to do this or that for your children or yourself regarding education.

Choosing the right school for you or your children can be incredibly expensive or surprisingly inexpensive.

As an optimistic benefactor, if you fall into the trap of, “I’ll pay for whatever school you can get into,” you are very likely to pay a fortune. Imagine the wide-eyed high school senior who received acceptance letters from three schools: the state university, a private school offering a one-half scholarship, and another private school offering no scholarship. The student just found out that two friends are going to the latter. How do you think that decision’s going to turn out? If, however, you offer parameters to guide the prospective collegiate, you may be surprised how economical the college experience can be.

For the budget conscious, consider attending a community college for the first two years of a four-year degree. This was my path, and it served two purposes. First, it saved some money. Second, it allowed my educational maturation process to continue to develop (that’s putting it nicely). I transferred those credits to the four-year university from which I received my Bachelor of Science degree. The cost of tuition for the commuting community college student is still around $2,800—per year! Then, if you can commute to the state university as an in-state student, your cost would rise to approximately $8,400 per year for the latter two. This means you could get an entire four year undergraduate degree from an excellent state university using this method for $22,400 . . . less than your first semester at Harvard!

Having The Talk (no, not that talk)

An enjoyable part of the process—for students and parents—is the exploration of the student’s own Personal Principles and Goals. If you’re a parent reading this, set aside a weekend to take your student away and walk him or her through the Personal Principles and Goals discussion. A high school student isn’t likely to have well-stated goals and might not even be overjoyed with a discussion designed to articulate them, but the discussion of, “What is it in life that you want to be about?” can be affirming and encouraging. The results of this exploration can be very helpful in determining what schools would be ideal for a prospective student.

If you’re just beginning this search, do not rule out the private institutions based on the quoted numbers for tuition, room, and board. Many times it is private colleges and universities that have strong endowments and foundations designed to help students financially. The aid from private schools may not even be contingent on the financial well-being of the parents or the students. Oftentimes, a smaller, more selective institution may be looking for a diverse population and offer a financial incentive for you or your student based on a unique background, proclivity, passion, or hobby.

I know virtue underlies the “wherever you want to go” family education policy, but it ignores the reality that the college of your children’s choice might not be worth what they ask you to pay them, and (make sure that you’ve put away any weapons within reach before you read this next statement) the aspirations of your child may not be worth the price of admission (and tuition, room, and board). If your child shows an incredible aptitude for math and science, and specifically wants to become an engineer, then paying the price for MIT may be worth it for him or her. And since it is your child who would benefit financially from the additional clout that comes with an MIT diploma, he or she should see the logic of sharing in the additional cost. If your child has no direction (and there’s nothing wrong with that at the age of 18), but quite sure he or she needs to go to Penn State to experience tailgating in Happy Valley, that may not be a good value if you are a Virginia resident (with one of the best slates of state universities in the country).

Once your children reach high school, it is probably a good time to share the education plan with them; it’s always good to get to your kids before they start hearing conflicting reports from their friends. (A wise mentor gave my wife and me the excellent advice to be the first parent to have these benchmark discussions to pre-empt whatever they may hear from friends at school.) But remember not to make any promises you might not be able to keep.

If there is ambiguity regarding your financial ability to follow through on a plan, be honest with your children. We parents tend to have a fatal flaw when it comes to acknowledging our own shortcomings with our children. It’s a defense mechanism. We’ve answered so many questions with an air of certainty as our kids grow up physically, mentally, and spiritually that we often subconsciously (or consciously) sweep any signs of our own personal failure under the carpet. We don’t serve our children well in this regard. Our kids have already learned that they are not perfect, and we can teach them a more realistic, useful lesson by acknowledging our own miscalculations and showing them how to navigate them.

If you are developing your own education policy without the aid of parental (or other) benefactors, take into account the probability of being able to pay your loans back with the education you receive. The income you will make after school does have some bearing on what you should be willing to pay (and especially borrow) for your schooling. If you’re planning to be in international banking, getting an MBA from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania is going to be expensive, but you’ll likely be making enough after graduation to pay those loans back, making the learning experience both priceless and valuable.

If instead you’re planning to give your professional life to social work or the pastorate, two of the more noble paths one can choose in life but that are known for underpaying, it may not make sense to get your undergraduate degree at Yale if you’re not receiving any subsidy from the university. It will cost a fortune, and the debt will saddle you for years to come without the substantial discretionary income to pay it back. You may more ably meet your goals by choosing the community you’d like to serve and going to the local college or university connected to that community.

As the undergraduate degree has become more of a minimum requirement than a resume builder in the last couple of generations, the cachet derived from the institution’s name on the undergraduate diploma has decreased. It is now the graduate degree that has become more of a differentiating factor. This would suggest that if you are going to get the best value out of your education, you’ll be better rewarded to pay up for the elite name on your graduate school diploma than on your undergraduate.

U.S. News & World Report publishes a detailed list of the “Best Graduate Schools” on an annual basis, segregating among the best business, education, engineering, law, and medical graduate schools. Included in their ranking criteria is the anticipated increase in pay. You can view their annual findings on the following website: http://grad-schools.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best-graduate-schools/.

Once you have your family education policy established, it’s finally time to determine an education savings plan. The number that most often arises in conversations of this type is 529. Named after the IRS proclamation bearing the same number, 529 plans are tax-privileged education savings vehicles. They are plans administered by states, but you are not necessarily restricted to using only those available in your state. There are two types of 529 plans: prepaid tuition plans and college investment savings plans.

Prepaid tuition plans are designed to shelter education savers from future increases of the cost of tuition. With the cost of education rising at a rate faster than inflation in many instances, the benefit of a prepaid plan is that you can lock in today’s cost for future education. But prepaid plans are typically tied to the state in which you live and pledge only to shelter you from the increase in costs in your state.

College investment plans are those to which you contribute funds that are invested in options like mutual funds or age-based target-date portfolios that grow increasingly more conservative as the time draws nearer for the student to use the funds for qualified education expenses. The good news with the investment plans is that they are more flexible; you can use the funds for a wide array of education expenses (including room, board, books, computers) and tuition at schools outside of your state. The bad news is that the investment choices inside of 529 savings plans have inherent risk, a lesson that many investors learned the hard way in late 2008 and early 2009. Several mutual fund managers are now under scrutiny for having delivered big losses in target-date portfolios designed for capital preservation toward the end of the saving cycle.

The primary benefit derived from 529 education savings plans is tax-free growth on the dollars invested in the plan. As we mentioned in the last chapter, 529s work most similarly to a Roth IRA. You put after-tax dollars in the 529; the investments inside presumably grow in value over many years; then the distributions you take for qualified education expenses are tax-free distributions.

As a parent, you can set one such account up with your spouse as a joint owner (in some plans) or as a successor owner (in other plans). Your child would be the beneficiary. There is a profound difference in the way these accounts function versus their education savings predecessors, the UTMA (Uniform Transfers to Minors Act) and UGMA (Uniform Gifts to Minors Act) accounts. When you use an UTMA or UGMA account, you are the custodian, not the owner; the child is the owner. You, as the custodian, are only watching over the money for the child, and if the child chooses to take that money and run when he or she reaches the age of majority, that is the child’s prerogative.

With a 529, you, as the parent (or grandparent, aunt, or uncle), are the owner—it’s your money—and the child is the beneficiary. If Johnny decides to ply his trade outside the classroom, you can simply change the beneficiary to another child. You are in control, and that is one of the primary benefits of a 529 savings plan. Even if all of your children decide not to go to school, you could change the beneficiary to yourself and use the funds for an accredited golf school or basket weaving academy.

Contribution limits are quite liberal. An individual is able to contribute up to $13,000 per year (in 2011) and joint gifts of $26,000 are allowed. Additionally, lump sum contributions are allowed equaling the aggregate of five years worth of contributions. In 2011, an individual can prefund five years of 529 savings plan contributions up to $65,000, or $130,000 for a joint gift. Most young parents don’t have that kind of money to contribute to a 529 plan, but this is a strategy that works very well for wealthy grandparents attempting to reduce their estate’s size to avoid federal or state estate tax. After a maxed-out lump-sum contribution is made, no additional contributions can be made for five years.

There are savings plans that are sold by brokers who receive commissions and plans that are no-load, directly handled by the state and the mutual fund company sponsor. Since none of the plans have an ideal list of investments from which to choose, it will rarely make sense for a saver to give up three percent to six percent in sales commissions for every dollar invested. Even the best investment manager will simply not have the tools available to create a truly optimal portfolio mix. Most savers will be best served with a no-commission 529 plan. Additionally, many states offer a state tax deduction for contributions made to a 529. Many of those require you to contribute to your state’s plan in order to receive the deduction, but some will allow you to deduct contributions (up to certain limits) for contributions made to any plan.

Two valuable resources in hunting for the right 529 savings plan for you are www.Morningstar.com and www.savingforcollege.com. Morningstar publishes a report on “The Best and Worst 529 College-Savings Plans” each year. Savingforcollege.com is a web site dedicated wholly to college savings plan information. Their content is useful, but be careful—they show a blatant economic bias exhibited front and center on their web site.

Consider utilizing investment savings plans if you’re saving for younger children. When your children are younger, you have absolutely no idea where they’re going to go to college, if at all, and so you may not want to hem them into only the state schools with the prepaid tuition plan. A 529 savings plan is also a great way to set up a receptacle into which grandparents, aunts, and uncles can make gifts when the time comes for birthdays and holidays. I even recommend that you inform them of the plan’s existence. Besides, how many race cars, superheroes, dolls, and video games do our kids need anyway?

![]() Economic Bias Alert!

Economic Bias Alert!

The web site www.savingforcollege.com is a valuable resource for those researching the broad spectrum of available education savings plans. But their reputation in my eyes is significantly diminished because of a little box that rests in the center of the web site home page. It invites the user to “Find a Professional” (“Use our directory to find a 529 professional near you”). Curious, I put my zip code in and hit the “Go” button. What came up was a list of “529 Pros,” including even “Platinum 529 Pros,” who sell 529 plans for commissions. Not even mentioned was my state’s no-commission plan, lauded as one of the best in the country. It would appear savingforcollege.com is accepting advertising revenue from parties who stand to reap a commission from a 529 sale, therefore elevating them to some form of “Pro” status on their web site. A representation such as this diminishes the credibility of the resource and the information they pass on because we’re left wondering how much of their guidance is tainted by their best interests instead of ours.

Your broker or financial advisor also has an economic bias regarding his or her recommendations for the right 529 plan. In my state, for example, the highly rated, low-cost, no-load 529 savings plan option is the only state-sponsored 529 savings plan. State residents receive a state tax deduction for the first $2,500 per plan contributed each year. However, that means financial advisors cannot be compensated for recommending the state’s 529 plan. I’m sure you find this shocking, but as a result, most advisors in my state tend to find fault with our state’s plan that has been heralded in third-party analyses. Many advisors have found plans in several other states that would appear to be “better”; not surprisingly, those plans all do offer a commission. As we’ve said many times, this doesn’t make your broker or advisor a bad person, but it helps color your thoughts when you’re analyzing the plan you own or are considering owning, so that you can make a more informed decision.

If you’re starting out later in the game, and you have a better handle on what you and your child’s expectations might be for a collegiate endeavor, the pre-paid tuition plan can be a wise place to put some of your college savings. The shorter the time horizon, the less the benefit of the investment savings plan (because you need to take an adequate amount of risk to outpace inflation anyway). The ideal for some savers may be a combination of the two 529 plans, but again, the prepaid tuition plan is primarily geared toward students intending to go to in-state schools.

Another consideration that has become even more apparent in the wake of the financial crisis is that with prepaid tuition plans, you are purchasing a promise from your state that they will cover your education bills in the future. Due to market losses, a growing number of states are now underfunded, like most corporate and state pensions. They owe more in the future than they could currently pay. As reported in NPR’s All Things Considered, “Alabama has one of the largest shortfalls, but other states with deficits in their prepaid tuition funds include Tennessee, South Carolina, West Virginia, and Washington.”1 You should research your state’s plan to determine its solvency and also establish what the state’s obligation is to keep their word. Some plans are absolutely guaranteed by their state while others require state legislative and executive collaboration to guarantee your future college funding in the case of a shortfall.

Do you recall when I mentioned earlier how much you’d have to save if you wanted to cover 100 percent of the educational costs for your youth? Those are accurate numbers, but I don’t actually want you to plan to save 100 percent of your expected college supplement in 529 plans.

I want you to save 50 percent. Call it The 50 Percent Rule.

The benefits of 529 plans are many, but their faults mount up as well. For every inch of tax privilege received, you give away freedom, flexibility, and excellence. Like corporate-sponsored retirement plans, 529 plans have a limited pool of investment options, and especially in difficult investing environments, the limited options may not give you the best chance to shelter your money from losses and take advantage of gains.

Where is the other 50 percent going to come from if you’re only saving half of your goal in 529s? Cash flow at that time, scholarships, loans, and the missing ingredient in most people’s balance sheet, the liquid investment account. You’ll recall discussing this in our investment chapter. The liquid investment account is that in which you pay taxes when interest is earned and when capital gains are taken, but you have no restrictions on what that money can be used for and when you can use it. This account could be used for a home addition, a pool, a down payment on a second home, supplemental retirement savings, or if need be, your or your children’s education.

Timely Application

Family Education Policy and Savings Plan

If you’re starting from scratch, the following application steps will provide a great starting point; if you’re re-evaluating, this will be a great opportunity to hone your approach.

Create your Family Education Policy. If you are one of two parents, put your minds together. If you’re a single parent or loner in your educational quest, your policy may be even more important. It may be helpful to pull out your Personal Money Story exercise, which likely includes some good or bad experiences you’ve had surrounding the cost of your own education. Then, review your Personal Principles before articulating your educational savings goals. Utilize the Family Education Policy worksheet to solidify your family’s plan, and then, at the appropriate time, share it with your children.

From that policy should spring your education savings plan. Use the calculator we provide to help you determine what your monthly savings should be and how much of that should be going into a 529.

Visit www.ultimatefinancialplan.com to find templates to use for your Family Education Policy and Savings Plan worksheets.

Tim Maurer

A great college education is not priceless, but it is invaluable.

It is difficult to keep this in perspective, because we are dealing with our children, their lives, and their futures. While I realize you would give up virtually anything in order to create a benefit for your child, it is important that educational expense fit into your overall plan proportionately.

You have probably heard countless times the flight attendant’s speech involving the loss of oxygen in the aircraft. In that case, the oxygen masks will drop down from the panel above you, and those of you traveling with children should “secure your own mask first before helping others.” This is not because you need oxygen more or sooner than your children. It is because, unless you take care of yourself, you won’t be there to help them.

Whether you are a student or a supportive family member or friend of a student, the logic is the same. Enlightenment and learning are incredibly satisfying ends. Traditional education is a means toward those ends and must fit within realistic financial parameters lest it become a liability.

1. This was reported on NPR’s All Things Considered on May 18, 2009 in a segment by Debbie Elliott, Market Slide Snags Alabama Tuition Program. You can read or hear the report by following this link: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=104268001