Chapter 21

The Unreasonableness of Art and Artists

After Edye and I moved into our current home in Brentwood, we decided we wanted artwork as bold as the house itself. We knew exactly who to call: Richard Serra. He’s America’s greatest living sculptor, because he is brilliantly original, his work is always evolving, and he does things with steel that no one else would think possible.

I vividly recall the day Richard came over and walked around the yard, visualizing where the sculpture would go. His initial concept involved four 40-foot-tall steel columns. I pointed out that Edye and I live in earthquake country, which would make such a work unwise if not impossible. So Richard came up with a proposal that merely was unreasonable.

He wanted to stand four steel panels, each 15 feet high and 21 feet long, on the lawn and curve them into each other like a nest. Each steel panel would be 2 inches thick and weigh 15 tons. No place on the West Coast could handle that sort of job, so the panels would have to be fabricated at the Lukens Steel Company in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, and then shaped at the old General Dynamics plant in Rhode Island. General Dynamics was willing to take on the work to fill the hours when they weren’t building nuclear submarines.

Then, because the panels were wider than any highway lane and taller than most overpasses, they would have to be trucked on four separate flatbed trucks across the country with multiple police escorts. When they arrived, we would have to rip out some trees and walls to install the piece. Because no helicopter could carry that weight, our steep driveway would have to be lined with steel plates and strengthened with concrete beams so that each piece could be put in place. I started to wonder if that was how the pyramids were built.

When Edye and I suggested to Richard that this sounded a bit too unreasonable—even for me—he assured us: “It’s really no problem. Don’t worry.”

We gave Richard the go-ahead. His panels finally arrived around midnight the weekend before Thanksgiving. We got a phone call that a package was at the door, as if it were a Federal Express delivery. On the side of each panel, written in chalk, were the words “Not submarine work,” just to be clear.

At one point, we reminded Richard there was no title for the work. Edye recalled what he had told us about the installation, and her wry humor came to the fore. She suggested, No Problem. The name stuck.

Why I Collect

More than one guest has taken a look at No Problem and asked, “What the heck is that?”

I had the same reaction when I first began looking at contemporary art. I didn’t get it. People like Cy Twombly with his pale, repeated marks on canvas and Frank Stella with his complex metal works were posing provocative questions not only about the nature of art but also about perception itself. Of course, I didn’t know all that at the time. I was experiencing what the art critic Robert Hughes called the shock of the new.

The first artwork we purchased was a drawing by Vincent Van Gogh. It was a nice, peaceful scene of two thatched huts. You didn’t have to wonder at it, and it certainly wasn’t jarring, but after several years I grew a little tired of it. I needed something that grabbed me—and that didn’t have to be put in a drawer for six months out of the year to keep it from fading. I set up a trade so we could acquire a Robert Rauschenberg red painting, which remains in our home today and still is one of my favorite pieces.

I moved into contemporary art for a number of reasons. It was, in part, a homework-based decision. I knew that the best collections were generally built at the time the artists were alive. That way, the collection represents an era and the collector’s personal taste. Your money also goes further when you’re placing bets on the future.

Mostly, though, I decided to collect contemporary art because it moves me and it makes me think. It was risky because you never know whether an artist you support will maintain his or her reputation. Critical opinion, which drives markets, is subject to fashion. A drawing by Van Gogh is a safe bet—a Jeff Koons Balloon Dog less so.

I also enjoy meeting artists and watching them work. They’re unlike anyone I meet in business. By definition, artists are “Why not?” thinkers. They do what no one else would think to do. They often work very hard without seeing great returns or receiving any particular acknowledgment in their lifetimes. They tackle, with brutal honesty, the politics and social issues of their times. They follow their vision no matter how strange it seems according to the conventional wisdom. I can relate to that. I wouldn’t trade the opportunity to meet them and see them work for all the Van Goghs in the world.

By the early 1980s Edye and I had become such avid collectors of contemporary art that we started to run out of wall space in our home. But we wanted to continue collecting. We began to look for ways to share our collection with an audience far wider than our family and circle of friends. We hit on the idea of establishing a foundation that would function as a lending library for institutions, essentially creating a public collection.

Doing Homework—Even for an Avocation—Will Deepen Your Experience

Enjoyment and satisfaction increase with knowledge—even when it comes to hobbies.

Collecting contemporary art takes a lot of homework because you have to judge the work of a living person. When we consider buying an artwork, we think about where an artist fits in among his or her contemporaries and how the work would integrate into our collections. Most of all, we think about the work itself—how significant is it and how evocative? All of this research has enriched my life immeasurably and required me to use a different set of skills and a different part of my brain than I did in business. You should seek out a passion that allows you to do the same. It will enrich your life in ways business success simply can’t.

In the 1980s we took major risks with the works we purchased. Edye and I spent a lot of time in New York’s East Village, where we got to see work by up-and-comers like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, who once smoked pot in the bathroom of our house. The most exciting discovery of those years for me was photographer and artist Cindy Sherman. Edye and I weren’t photography collectors, but I was fascinated by Cindy, who would make herself over into all sorts of characters and then photograph herself—an interesting twist on the traditional self-portrait. In 1982 we bought several early black-and-white photos of hers for $200 each from a show in the basement of the trendsetting gallery Metro Pictures on Mercer Street. They were from a series she calls Untitled Film Stills, and I wish we had bought every one of those photos. I still enjoy the theatricality of Cindy’s works and the way they always surprise me. Today, we have the largest collection of her work in the world.

Sometimes we’ve been late to the game with an artist. In the mid-1990s, for example, a few years after I saw Andy Warhol’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, we began buying his art. I didn’t recognize the importance of his work until that show. Now we have a major group of his paintings in our personal art collection, including Small Torn Campbell’s Soup Can (Pepper Pot), which I bought for $11.7 million. Edye had wanted to buy a Warhol soup can print in the 1960s for $100 but didn’t for fear I would think she was nuts—which I probably would have. About 40 years later, she thought I was the nutty one. We were at that auction together when I bought Pepper Pot, but I had bid so discreetly that she didn’t realize I was the winner. After it was over, she whispered in my ear, “What idiot paid that much?”

In the end, whether you spend $500, $5,000, or $5 million, only one thing matters: You have to want to look at it. You have to love it. That’s priceless.

Pursuing a Passion Sometimes Means Casting Aside Your Business Sense

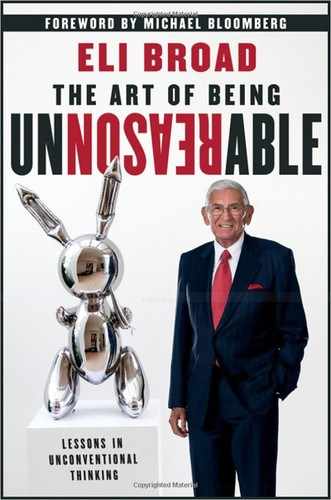

Jeff Koons is one of the artists to whose work I’m instinctually drawn. As we did with Cindy Sherman, Edye and I met Jeff in the 1980s in New York. I immediately thought he was brilliant. His background as a commodities trader was different from that of most other artists and piqued my interest. I found his art playful, fun to look at it, and, like Cindy’s, bold and theatrical.

But in the early 1990s, the art market was going through a recession, just like the economy in general. Jeff was having a hard time selling works and had trouble getting an ambitious and groundbreaking series of his called Celebration off the ground. The most important sculpture of the series, Balloon Dog, would require $700,000 to fabricate, just for the first of four planned versions of the work.

I decided to do something I rarely do—pay in full for works that have not yet been fabricated. I entered into a $1 million contract to fund the fabrication of Balloon Dog and another sculpture from the same series. I did it because I believed in Jeff and his work.

As he began work on the project, however, it became clear that the fabrication costs of Balloon Dog—an oversized sculpture reminiscent of a childhood balloon animal but constructed from reflective stainless steel—would exceed the earlier estimates. The dealers wanted me to cover the cost overruns, which I might not have done in business. But art isn’t business.

Nonetheless, I approached the situation as a negotiation with Jeff and his dealers. I immediately considered their incentives, which, fortunately, were aligned with mine: We all wanted to see completed works. In addition, the dealers wanted to sell at a strong price.

I suggested to Jeff that he increase the number of versions from four to five. For Jeff and his dealers, a fifth Balloon Dog would mean the sale of one more piece. Most collectors wouldn’t actively encourage the creation of more versions of an artwork because that means their piece is less rare. But I wanted my Koons artwork, and I wanted to help Jeff’s work take off again.

It worked. Balloon Dog was completed and became a very coveted piece. Our dramatic 12-foot-tall blue sculpture was shown as far away as the Guggenheim in Bilbao, Spain, and it most recently spent four years at The Broad Contemporary Art Museum at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

How Not to Get Distracted by Your Passion

I don’t like wasting time, so I got in the habit of working studio visits and museum trips into my business or philanthropic travel schedule. People often think it’s strange how briskly I go through museums. Sure, I could stand in front of each piece and stare at it for a good long time. But that’s not me. Usually I’m there to learn and apply my knowledge to our collections. As much as I would like to stay, I have to move on.

While I may dash through a museum, I do give myself time to take in artists’ studios and art fairs in Miami, London, Venice, and Basel. The experience of an artist’s studio is always inspiring and sometimes unusual. Some years ago, for instance, I dropped by British artist Damien Hirst’s studio only to be handed a protective astronaut-like suit so I could watch him lower a shark’s carcass into a tank of toxic chemicals. Although that’s probably not everyone’s cup of tea, I loved it. Browsing art fairs is just as enriching for me—it’s exciting and intimate, and it lets me into a world I would never have known if I had stuck to business. Sometimes it’s just plain fun.

Take the Art Basel fair in Switzerland in 2009, where I had the chance to give some art advice to an aspiring collector. I was walking through the fair with Edye when I saw a lot of cameras pointed at some guy wearing a hat and sunglasses even though we were inside. I had no idea who he was, but I’ve never been one to resist a camera. I walked right up to him and looked at the artwork he was contemplating—a 9-foot-long Neo Rauch painting of a race track, Etappe. Our foundation has a fair number of works by Rauch, a native of East Germany whose work combines the seemingly contradictory influences of socialist realism and surrealism. We discussed the work and the artist, and I said it was a good piece and we would probably buy it if he didn’t. He ended up purchasing the work. After I had walked away, Edye finally told me who I had been talking to: Brad Pitt. He has a good eye.

A Passion Is Not a License to Spend

Just as I don’t spend more time than I can spare on art, I don’t spend more money than necessary either. I always look to leverage what I do spend.

One of my attempts to do that has entered art world folklore. In 1995 I purchased a classic painting from Roy Lichtenstein’s high pop period titled I . . . I’m Sorry. I had first seen the painting on the wall of dealer Holly Solomon’s New York living room. It depicted a comic-book blond—actually, it was supposed to be Holly herself—weeping a lone tear and apologizing in a speech bubble. I liked it on first sight, but it would be 15 years until I finally acquired it.

As I walked into Sotheby’s auction room that day and was given a paddle, I asked if it was true that they accepted credit cards. They did. As it happens, I had a high-credit-limit American Express card that gave me a frequent flyer mile for every dollar I put on it. I bought the Lichtenstein for $2.5 million—which I knew was a fair price because other Lichtensteins of that period were selling for a lot more—and I put the purchase on my card.

It caused quite a ruckus. Sotheby’s had to negotiate down the transaction fee with American Express. People wondered what I would do with that many frequent flyer miles—actually, I donated them to students at CalArts. The real reason for charging the purchase, which shouldn’t surprise you by now, was the interest. Rather than handing over $2.5 million up front, I could keep my money invested, earn my usual high return, and pay for the piece when my AmEx bill came due, a little more than a month later.

When the next season’s sales rolled around, Sotheby’s auctioneer called me out and got a big laugh from the crowd: “We no longer take credit cards . . . Eli.”

For Even Greater Rewards, Share What You Love

No matter what your pursuit, the most fulfilling part is sharing it with others. You wouldn’t want to cook gourmet meals just for yourself or perform on the piano only in private.

But art can be different. A lot of collectors in the world want to buy an artwork just so they can look at it or say they own it. Edye and I have never felt that way. If we buy a work, it’s because we want a lot of people to be able to see it. When The Broad Contemporary Art Museum opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, I told Director Michael Govan he could borrow any works from our collections, including those hanging in our house. He came in and practically stripped the walls, and we were delighted.

Although The Broad Art Foundation has made more than 8,000 loans to nearly 500 museums since 1984, there still was the question of what Edye and I would do with our personal art collection after we passed away. We had a few options: split it up between a few museums, create a small gallery but continue primarily as a lending library, or build our own museum. Most museums keep the bulk of their art in storage, which we didn’t want to happen to the pieces in our collections. A small gallery, even with an aggressive lending policy, would have the same effect—hiding most of our collections from public view. And as they kept growing to nearly 2,000 works, we realized no museum could ever show more than a few of our works at a time.

Building a museum was the most challenging option but also the most rewarding. The Broad will allow our collections to stay whole and be accessible to the greatest number of people in Los Angeles and in museums worldwide. With the Museum of Contemporary Art across the street, our museum will make downtown Los Angeles a nexus for contemporary art and jump-start further development in the area. It also will serve as the headquarters of The Broad Art Foundation’s lending library, making sure that all our art does what it was made to do: bring beauty, inspiration, and the shock of the new to as many people as possible.