Chapter 10

Leverage

If you have ever bought anything on credit, you’ve used leverage.

Let’s say you put some money you had saved down on a car and finance the rest. With the loan, you have to pay five years of interest—not an inconsiderable sum. But you get the car right away, and all the opportunity it brings: picking up your date, taking a road trip, and of course, driving to your job to make the money you need to pay off your car loan. The car may not be “worth” the money you paid plus interest—certainly not after you’ve driven it around for five years—but living without a car carries its own costs.

Without the loan, you would have whatever amount you had for a down payment, but you would have to spend at least a few years saving up the rest of the car’s purchase price. And you would probably be taking the bus—making it that much harder to do everything you want to do, including making a living.

The loan is your leverage—it’s what enables you to do more with your money.

But leverage isn’t always money. Sometimes it’s about channeling your energy and effort, enlisting the help of your friends and colleagues, applying technology, working with the press or social media, or mentoring someone who goes on to mentor 10 more people.

I’ve used leverage to increase capital for my businesses, but I’ve also used it to get the most out of my marketing, to raise funds for civic initiatives, and to do more in philanthropy than we possibly could have with our money alone.

Think of the literal meaning of the word leverage. It refers to levers—tools that amplify your power to move something. They’re everywhere, and you should always use them when you can.

Some Straight Talk About the Mother of All Loans—Your Mortgage

Buying a home using a mortgage is the best opportunity most people have to leverage their money.

I recognize the reluctance to get a mortgage. When we bought our first house, Edye always said that she hated the idea of “mortgaging the nest.” Despite not carrying mortgages myself, I still think they’re one of the best forms of leverage when used correctly. In fact, they were essential to the spread and growth of American wealth in the twentieth century. The benefits that flow from being a nation of homeowners are incalculable.

Mortgages are dangerous only if you let them control you. If you agree to take on a mortgage you can’t comfortably carry, then you’re going to get into trouble. That’s part of what inflated the housing bubble. When it popped, it triggered the financial crisis we are living through today. But a mortgage you can handle is a great way to use leverage.

As in the case of the hypothetical car, when you buy a house, you’re getting a lot in return, even if the house will never be worth what you end up paying after 30 years of principal and interest. But you’re buying a home where you can live with your family, developing a stake in a neighborhood and a community—and by not paying rent, you’re building equity in an investment. You’re earning good credit if you pay your mortgage on time. And you can purchase what you never could have afforded using only your own money. Plus you get tax deductions on your mortgage interest.

When interest rates are really low, you should pay as little down as possible. I know this sounds risky, especially considering the recent housing crash. But it works as long as you invest money that would have gone into a down payment in a solid mutual fund that appreciates at a higher rate than the mortgage interest you’re paying. You’re increasing the value of your dollar by using someone else’s money.

Spread the Wealth—How to Leverage Doing Good

When you use a mortgage to buy a house, you’re using your dollars to help create stability for you and your family. And because of your mortgage, you have more money left over to do whatever you want: pay for your children’s piano lessons, start a business, or donate to a cause. Your mortgage increases the amount of good you can do for yourself, your family, your neighborhood, and the world.

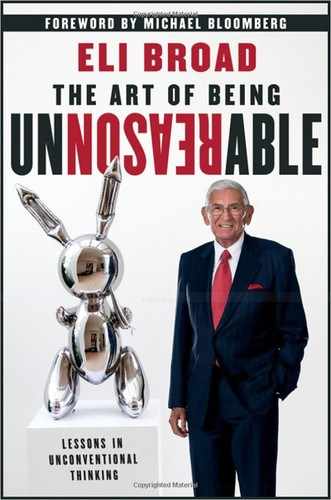

Imagine the power of leveraged dollars devoted solely to doing good. Edye and I had a lot more dollars for just that purpose after we merged SunAmerica with AIG. We established The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation to fund scientific research and education reform, the work of which I’ll discuss in a later chapter. We combined it with The Broad Art Foundation, which we had started in 1984, to create The Broad Foundations.

The Broad Art Foundation is a prime example of leveraging wealth to do more. Edye and I ran out of wall space for our art and wanted to keep collecting. We also wanted the contemporary art we loved to be accessible to the public, so we decided to create a foundation that would serve as a lending library, a public collection from which museums could borrow works. Rather than keeping our collection to ourselves, we leveraged the pleasure and stimulation the artworks could bring by making them accessible to audiences around the world.

Extend the Power of Your Dollar—Find Money That Costs Less Than Yours

As our personal and foundation art collections grew to approach 2,000 works, Edye and I decided we wanted to have a permanent home for them. Estimates suggested building a museum would cost between $100 million and $150 million. That money would have to come from the same pot Edye and I use to fund all of our philanthropic efforts. The withdrawal of that much money would mean that the foundations’ portfolio would earn significantly less, thus reducing the amount we had available to give to grantees. We had to find a way to use leverage to avoid an outright payment of tens of millions of dollars.

As we thought about the museum, Edye and I wanted to create an institution that would exist in perpetuity, long after we were gone, so we formed a new nonprofit to build and operate the museum. To ensure its independence and longevity, we appointed an autonomous governing board of professionals with strong financial, artistic, and organizational expertise.

The museum board recommended that we leverage The Broad Foundations’s assets to pay for the construction and operation of the museum. The board asked us to award a multiyear grant to the museum so that it could use that pledge as collateral to borrow the money.

The museum board then decided to issue tax-exempt bonds, something a nonprofit can do at a low interest rate. That’s how museums like the Getty, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art have raised money to construct new buildings or finance expansions.

The museum sold $150 million worth of Aa1-rated bonds, promising to pay them back in 10 years at 3.13 percent interest. Investment bankers told us it was crazy to expect that a brand-new entity with no credit history would get even an A1 rating. But we picked Morgan Stanley as our underwriter because they believed it could be done. They and our team of lawyers delivered what conventional wisdom said was unreasonable.

The bond’s sale was a win for all parties. Our foundations preserved their endowment so that the earnings could continue funding work in education reform, scientific and medical research, and the arts. Bondholders will get their money back, plus interest. The museum received the money it needs to build. And the people of Los Angeles will get a new museum.

If possible, you should always try to make leverage work to save you money. If the interest on a loan is lower than what you earn on your investments, always take the loan. There are risks—if your investments falter, or if the loan comes with particular conditions—but if you’ve managed the risks properly and are confident of your investments’ strength, you’ll be in great shape.

Leveraging People and Effort Works Just as Well as Leveraging Money

Leveraging isn’t just about money.

I learned that on my first major fund-raising campaign. When raising money for the Museum of Contemporary Art back in the early 1980s, I had far less money available to give to good causes. I put up $1 million—a lot for our family then—because that was as far as we could go. (If you’re giving money and you want to do it right, make it hurt a little. That will keep you invested in what you’re doing and make you watchful of the cause you’re supporting.)

But I didn’t stop my work there with a donation. I organized the overall fund-raising campaign, using my initial contribution as my leverage. I told everyone I knew who had the ability to donate that I had put up some money, so why shouldn’t they? I never could have given $13 million outright, but that’s the total we reached—$3 million more than the city required before they would release funds to build the museum.

More recently, Edye and I used our philanthropic dollars to leverage government spending. We saw a perfect opportunity when Californians approved a $3-billion ballot proposition in 2004 to fund stem cell research. At the time, federal regulations severely limited labs funded by federal dollars from pursuing embryonic stem cell research.

Because almost all California labs received some federal funding, Edye and I quickly realized that the state needed new facilities where stem cell research could be conducted without restriction. I had read about the issue and saw, as a layperson, the potential of stem cell research. We started with the University of Southern California (USC), where I sat on the board of the USC Keck Medical School, and gave them the funds to build a stem cell research center. Then we gave to UCLA, which had usable buildings but lacked operating funds and the necessary equipment. We also made a grant to UC San Francisco, where we were impressed with the work of young scientists and the quality of the researchers, to build a cutting-edge center. By the time we were through, we had given a carefully targeted $75 million to create badly needed institutions.

Although we had no grand plan at the time we made these donations, I do see biomedical research as essential to the economic future of California. Over time our investments will pay off not only in lives saved or made livable, but also in jobs and greater prosperity for our state.

If you’re using leverage to do good, talk up what you’re doing, whether it’s making a donation or volunteering, and persuade others to join you. Leveraging dollars is important, but your time and energy are among the most valuable resources you have—why not make them go further?

I’m particularly proud of our use of leverage in education reform. That’s where we’ve managed to leverage the work of hundreds of smart, driven professionals.

We recognize that a great teacher in every classroom is the most important factor in a student’s success. But it would be virtually impossible for us to work with the millions of teachers in classrooms across America. By focusing our efforts on training school district superintendents—essentially the CEOs of school districts that are often larger than many Fortune 500 companies—we realized they had the power to put effective teachers in every classroom.

Our superintendents extended the reach of our money many times over. We couldn’t afford to train 100,000 teachers. But we could train 100 superintendents, who could have an impact on more than 100,000 classrooms.

If you’re a teacher, I admire you, and you already know the power of leverage. You devote your time and energy to educating children, who grow up to be innovative, productive, and philanthropic adults. Every hour you give, the world will get back many times over. The value of that effort is priceless.