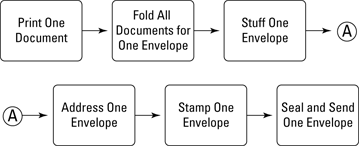

Figure 2-1: A batch mailing process.

Chapter 2

The Foundation and Language of Lean

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding the foundation of Lean

Understanding the foundation of Lean

![]() Learning Lean terms and expressions

Learning Lean terms and expressions

![]() Identifying waste

Identifying waste

If you’ve ever closely watched an elite professional — an athlete, actor, or artist — perform their craft, you’re amazed by how natural and effortless they make it seem. Sometimes, what they do just doesn’t seem humanly possible — just ask any weekend golfer or home do-it-yourselfer. What these professionals will tell you is not only how long it’s taken them to achieve their status, but also that they’re never done — they can always get better.

When you undertake a Lean journey, at first it may feel like you’re trying to become a ballet dancer or an auto racer. It’s new, different, and uncomfortable. The practices may seem strange or even counterintuitive. But with time, education, disciplined application and understanding, you’ll become a Lean professional. To start your Lean journey, in this chapter you’ll learn about its principles and unique terms.

Understanding Lean Basics

Chapter 1 explains the context of Lean: what it is, where it came from, and how closely aligned it is with the Toyota Production System (TPS). As you come to understand Lean even more, you’ll learn that there’s not a single concise definition. Lean experts and practitioners don’t even agree on a single set of standard principles. There is a generally accepted framework and tool set for Lean, as well as, foundational beliefs and leadership models. Collectively, they form the broad practice known as Lean.

Creating the foundation

Six basic principles of Lean include: customer value, value-stream analysis, everyday improvement, flow, pull, and perfection. Lean always starts and ends with the customer; it is the customer, — and only the customer — who defines and determines the value of the product and service. Further, the value stream is used in Lean to describe all of the activities that are performed — and the information required — to produce and deliver a given product or service. To create value in the most effective way for the customer, you must focus on improving flow, applying pull, and striving for perfection. (More on this in Parts III and IV.) And you implement Lean through people who are respected, engaged, innovative, and empowered.

It’s always all about the customer

The underlying reason for being in any business endeavor is to serve a customer successfully. Your customers are your focus: Without your customers, your business effectively doesn’t exist. Your customers define what they value and what they don’t. The customers set the expectations, and they respond to your offerings with their wallets and their opinions. The fundamental premise for all Lean organizations, and the first step of any Lean undertaking, is to identify your customer and what they really value — what they want today and tomorrow.

Everything you do in a Lean organization is ultimately focused on serving your customer in the most effective way. All of the organizations that comprise the value stream must understand what their customers want, translate that into a product or service that the customers will buy, and provide it at a price they are willing to pay.

![]() The customer must be willing to pay for it.

The customer must be willing to pay for it.

![]() The activity must transform the product or service in some way.

The activity must transform the product or service in some way.

![]() The activity must be done correctly the first time.

The activity must be done correctly the first time.

You can find more about customers, consumers, and tools to understand them in Chapter 6.

Scrutinizing the value stream

When you go into your local supermarket to buy groceries, have you ever stopped to think about all the activities that had to occur, in just the right sequence, in order for you to readily buy what’s on your list? Consider produce, for example. You can now find about any fruit or vegetable in your market year-round. Looking in the produce section, you’ll find products from around the globe. The produce has more frequent-flier miles that you do! From the fields, through transport, to your store, and ultimately to your table, hundreds of events have occurred precisely the right way and at precisely the right time in order for those blueberries to be available to you at a price and a freshness level that you’ll buy.

Delivering value to customers occurs through what’s called the value stream. In an ideal or perfect world, the value stream consists of only value-added activities. That ideal is what you aim for, but in reality, nothing’s perfect. Some waste exists in every process. (We introduce you to the various types of waste in the “Waste not, want not” section, later in this chapter.)

When analyzing the value stream, you identify all the activities and events that occur to get the product or service to your customer, along with the corresponding information flow. These activities and events may occur at your facility, or they may be earlier in the value steam at a supplier facility or later in the value stream in distribution or delivery. Generally, a business begins its improvement efforts with what it controls directly, and later expands beyond its organizational boundaries.

In Lean, you use a tool called a value-stream map (VSM) to capture and specify the activities, information, timing, and events in the value stream (value-stream mapping is an important activity, and we cover it extensively in Chapters 7 and 8). First, you scrutinize and map the value stream in its current state: How does it all work today? Then you envision the ideal state: How would the value stream look if you could do it all perfectly? This Ideal-State value-stream map enables you to visualize and understand what the value stream would look like with no waste — only value-added activities — perfection.

After you’ve defined the current and ideal-state value-stream maps, you work to close the gap between the two states. Usually a Lean team conducts kaizen (continuous improvement) activities to identify and implement the next future state moving you closer to the ideal state. Everyone from the organization in and around the value stream is involved in kaizen, both as individuals and as part of teams. Initially, most organizations begin their Lean implementation with kaizen in a workshop environment. Teams of people use Lean tools to significantly improve a segment of the value stream quickly — typically in a three- to five-day period. In a mature Lean organization, kaizen is part of daily business activities. (Chapter 9 addresses kaizen in detail.)

For you to design, develop, or deliver any product or service, you need information — lots of information! You need it the right way, at the right time, in a flow that effectively supports the flow of the value stream. You identify this information right in the value-stream map. For example, when a consumer buys something, you decrease inventory. To maintain product flow and replenish the inventory, information must flow from the retail outlet to the suppliers. Companies like Coca-Cola, Staples, and Ahold use Business Process Management (BPM) systems so that from the moment of purchase, the information triggers replenishment.

Keep it flowing

Customers and end consumers want their products and services fully finished. They don’t want a bunch of in-process, partially finished anythings. They don’t care about what’s in process, and they don’t care about your internal machinations! One of Lean’s central principles helps you deliver smooth, continuous flow.

The ideal state of the value stream in Lean is single-piece flow, in every process, with no stoppages anywhere. Multitasking, inventory stoppages, broken equipment, and batching are all inhibitors to flow and must be eliminated. When you have flow, everyone keeps the system moving at just the right speed to deliver the right amount at the right time to the customer.

In the Lean world, you apply the concept of flow to everything, including and especially discrete products and services. Ideally, from the time the first action is stimulated in the value stream, products and services never stop until they reach the customer. From the moment of customer demand, they continuously make their journey through a set of only value-added activities until they reach their destination.

Think about that for a moment: What would it take for a product or service to never stop — ever — in the process of moving through successive steps from first creation all the way to consumption? Imagine a medical facility where the patient never had to wait for treatment. Or buying the latest techno- gadget on its first day in the market without waiting in line, or finding out it sold out in the first 20 minutes.

In a manufacturing environment, flow requires a system of development and processing that adds value to each component, one at a time, with no interruptions, no standing inventory, no defects or rework, and no equipment breakdowns. Processes are synchronized precisely to the customer’s rate of consumption. Parts III and IV show you tools to apply to create flow processes.

This concept of flow is not the way people usually tend to think, nor the way most of us have been trained. People tend to organize things in groups and batches, but in Lean you think in terms of single-piece continuous flow. Take a simple activity like bulk mailing, for example. What type of process would you use? Figure 2-1 shows a flow chart for a batch process. Now look at Figure 2-2, which shows that same process in as a single-piece flow. In single-piece flow, the documents are handled less, use less space, and are finished and able to be sent more quickly to their recipient. Yet most people think it’s faster to process in batch.

Figure 2-2: A mailing process using single-piece flow.

For continuous flow to work, you must reduce variation and eliminate all defects, equipment breakdowns, rework, and outages of any type. These impede flow, whether you’re running a manufacturing, retail, service, medical, or support operation. The key to your success is in identifying and eliminating these barriers within the context of your world.

Pulling through the system

Think of products and services being pulled through a system as a result of customer demand, rather than being pushed through from previous process without any relationship to consumption by subsequent processes or the consumer. This is a pull system — a hallmark of the Lean enterprise.

The classic candy-factory scene from the old television show I Love Lucy is a perfect example of an unbalanced push system. Lucy is working on a line where chocolate candies arrive at her workstation on a conveyer belt, and her job is to put them into packages. At first, the chocolates arrive at a slow pace, and Lucy is doing fine. But then the belt mysteriously speeds up, going faster and faster. Lucy wants to do her best, and she tries to stay on top of it. But the inventory has no place to go. When it gets to be too much, she begins stuffing the candy down her shirt, in her mouth, wherever she can, so nothing passes her station. Finally, it all hilariously crashes to a halt. Waste, uneven flow, excess inventory, defects galore — all from pushing too much material at poor Lucy. Why the belt sped up, the audience never knows. What we do know is that this was not a Lean process!

In Lean, you use level scheduling practices to keep the system operating at a steady and achievable pace. You begin scheduling with the process closest to the customer. As the customer consumes a product or service, each step in the rest of the system is successively triggered to replenish what the next subsequent customer has consumed. In Lean, the pace of value-stream production is known as the takt time (see Chapter 7).

One of the most common examples of a pull system is your local supermarket (in fact, the supermarket was the source of inspiration for the pull system). A shelf space has a label that contains information for a given product. A specified amount of the product will fit into the allocated space. When the level runs low, the empty space acts as the signal for the stockperson to replenish the product. The tag contains the information about the product that belongs in the space.

This same idea governs Lean manufacturing. Instead of building up an excess of what’s called work-in-process (WIP) inventory, the customer’s demand for the product or service pulls goods through the system. The key notion is you only produce as the customer consumes. Think of it as “take one, make one.” A pull signal, known as a kanban, triggers the need for replenishment. Kanbans can come in various forms — a card, a light, a bell, an email, a container, or an empty space. Regardless of the form, the kanban signal contains the product information and quantities required for the replenishment of inventory. (More on this in Chapter 11.)

When successfully implemented, in conjunction with flow and perfection, pull systems result in higher inventory turns, reduced floor space, faster customer response, and improved cash flow.

Striving for perfection

Your ability to effectively provide value to your customer relates directly to your ability to eliminate waste and keep it away, permanently. This means that Lean is a never-ending journey. Although it may sound onerous, especially in a goal-driven society, the reality is that there is and always will be something to improve. As you scrutinize your processes, you’ll discover wastes that you didn’t know existed, because they were masked by bigger wastes. It’s like draining ponds or swamps: You never really know what’s lurking beneath the surface until you’re brave enough to look — and then you have to do something about it. Lean divides the broad category of waste into seven categories and three classifications (we cover these in the “Waste not, want not” section, later in this chapter).

Constant incremental improvements are achieved through kaizen. (We cover kaizen in depth in Chapter 9.) In its simplest form, kaizen means that you improve something every day. It is both a philosophy and a methodology. Kaizen improvements are generally not intended to be radical, earth-shattering improvements — instead, they’re regular incremental improvements that eliminate waste, here, there, and everywhere, bit by bit.

Companies just beginning a Lean journey often use what’s known as kaizen events. Kaizen events most often begin with workshops that offer a significant opportunity for the organization. This opportunity could be a visual impact through the use of what’s known as 5S (see Chapter 11), or it could be a customer-related opportunity like significantly reducing a specific quality defect. You can also use a kaizen event to take on an “it can’t be done” challenge and break through a barrier. An example of this is the reduction in equipment changeover time from hours to minutes.

When improvement is on a radical enough scale, it is known as kaikaku. When you think kaikaku, think “Throw out all the rules.” It may come in the form of multiple, simultaneous kaizen events (also known as a kaizen blitz). Alternatively, the term kaikaku may imply a complete change in technology or process methodology. You still use all the same tools of Lean (see Part IV), but you apply them to loftier goals.

Whether it’s through kaizen or the more ambitious kaikaku, the aim is the same: Strive for perfection through improvement. Eliminate waste in all that you do. Create a sustainable, thriving business for the long haul. Continually seek ways to better serve the customer.

Learning from TPS

Because Lean evolved from the study of the Toyota Production System (TPS), you might expect that the principles of Lean and TPS are similar. They are very similar, but they’re organized in a different way. To understand Lean, you need to understand a little about TPS.

Keep in mind that Lean and TPS are applicable across many industries, well beyond the automotive manufacturing environments that form their heritage. (This is the subject of Part V.)

Highly motivated people

Traditional organizations often operate with a “shut up and do your job” mentality. This is not the case in the TPS environment. In TPS culture, people are expected and encouraged to engage fully, not just to perform their daily job functions, but also to contribute to daily improvement activities. People use their creativity and provide important and useful suggestions to eliminate problems and improve the value stream. It is through the people — workers and managers — that improvement happens. The people use the tools, the people devise solutions, and the people implement improvements — it’s all about the people!

In TPS, people work both in their individual job assignments and also as part of broader teams. The teams may be natural workgroups or may be formed for special projects. As part of natural workgroups, team members are routinely cross-trained to expertly perform multiple job tasks across the team’s span of responsibility. Whether acting as individuals or as part of a team, everyone regularly and routinely eliminates waste as part of their normal work.

The approach of man-and-machine interfaces is philosophically different in TPS than in traditional Western-style environments. In TPS, machines are always subordinate to people. This means that processes are designed so that people don’t wait on machines — machines wait on people. Western approaches value the resource costs of people versus equipment and may conclude that the equipment is more valuable than the person, but this is never so in TPS. People are always most important. Machines, equipment, and systems are tools used by people as they add value.

Operational stability

The foundation of the TPS is operational stability. Operational stability means that variation within all aspects of the operations is under control. To have unobstructed flow, orders must be timely and accurate, schedules must be stable and leveled, equipment must run as planned, qualified staff must be in place, and standardized work must be documented and implemented.

One of the common mistakes that companies adopting TPS make is to not understand how TPS is a complete system, and how important holistic practices are to overall success. They think that implementing kanban is the answer — but without level and stable schedules, for example, kanban doesn’t work very well.

Visual management

Visual management enables people to see exactly what’s going on and respond to issues very rapidly. One method of visual management is known as andon (a signal to alert people of problems at a specific place in a process). The organization responds according to the signal shown; the response follows the documented standardized work practice. TPS leaders expect workers to trigger an andon anytime they have an issue; this enables the leadership to better understand barriers to the standard and to address problems quickly. They know that no andons is a problem, and it will lead to missed opportunities to improve. See Chapter 12 for more information.

Other aspects of visual management include cross-training boards, production tracking, customer information stations, communication displays, and tool boards. (We cover the tools of Lean in depth in Part IV.)

Just in time

Just in time (JIT) is the most well-known pillar of the TPS house. JIT means making only what you need, when you need it, and in the amount needed — no more, no less. If you’re supplying JIT, you synchronize your entire system with the customer’s demands. This is where takt time comes in to play. A JIT environment is almost like an ecosystem where everything is working in concert with each other. If one element is out of balance, then the whole system responds and adjusts. For example, if a major quality or supply issue arises, a JIT system will cease overall functioning until the issue can be resolved.

To operate to JIT, you apply several techniques and practices, including

![]() Producing to takt: Use takt to connect the rate of production to customer demand.

Producing to takt: Use takt to connect the rate of production to customer demand.

![]() Standardized work: Create consistent methods and standard ways of working to reduce variation and provide a baseline for improvement.

Standardized work: Create consistent methods and standard ways of working to reduce variation and provide a baseline for improvement.

![]() Quick changeover: Develop the flexibility to produce a broader range of products over shorter timeframes.

Quick changeover: Develop the flexibility to produce a broader range of products over shorter timeframes.

![]() Continuous flow: Create a steady stream of products or services that flow continuously to the customer.

Continuous flow: Create a steady stream of products or services that flow continuously to the customer.

![]() Pull: Use customer demand to trigger the replenishment activities throughout the system. Note that the systems of pull and continuous flow in TPS map directly to the concepts of pull and flow in the Lean framework.

Pull: Use customer demand to trigger the replenishment activities throughout the system. Note that the systems of pull and continuous flow in TPS map directly to the concepts of pull and flow in the Lean framework.

![]() Integrated logistics: View all aspects of your supply chain as a system, and manage them as a whole. (See Chapter 11 for ways to do this.)

Integrated logistics: View all aspects of your supply chain as a system, and manage them as a whole. (See Chapter 11 for ways to do this.)

Jidoka

The term jidoka means that you build in quality at the source. Recognize that quality cannot be “inspected in” — after the work has left its station, it’s too late. When practicing jidoka, accept no defects, make no defects, and pass no defects.

The philosophy of jidoka says the person producing work within any given step has the responsibility for the quality of job they are performing. If a problem exists, that person is responsible for resolving it. If the person can’t resolve the issue, then he is responsible for stopping the process in order to get it fixed.

The broader definition of jidoka includes root cause analysis techniques like the 5-Whys and mistake-prevention techniques like poka yoke (see Chapter 11 for more information) where you implement tools to physically prevent mistakes from happening. Visual management techniques like andon boards are also part of a jidoka practice.

Building on the foundation

Beyond the basic ideas of customer value, the value stream, flow, pull and perfection are additional principles of Lean, when coupled with the learning from TPS, lead to the mindset, methods, tool sets and techniques of Lean. When you truly get this wisdom, you get Lean.

Respect for people

Fundamental in Lean is a respect for people that does not exist in most traditional systems of management and leadership. Lean organizations are learning organizations. They effectively support their members through safe work environments, open communications, extensive training, and, in some cases, employment guarantees. Employee cross-training develops the employees, while at the same time adding depth to the organization. People are rewarded for making improvements to systems. People who are knowledgeable about multiple aspects of the value stream enable the organization to minimize variation due to absenteeism and turnover.

In a Lean environment, employees are expected to use their brains for the betterment of the customer, the value stream, and the organization as a whole. They engage in the environment, contribute to improvement, learn from their mistakes, and expand their knowledge base.

People always have more value than machines. In traditional manufacturing environments, it isn’t uncommon to see a person standing at a machine, watching while the machine cycles. Lean views this as a waste of the most precious resource — a human being. The Lean view is to implement appropriate technology, so that people can do more valuable work. This is part of the practice of autonomation (automation with a human touch). It isn’t the belief that people can be replaced with machines; rather it’s the practice to add intelligence to machines to detect defects, prevent issues from being passed along the value stream, and automatically unload parts, so people don’t have to waste their time and brain power watching a machine.

Make it visual

Transparency helps you eliminate waste. When you can quickly see what’s going on, you don’t waste time, energy, or effort trying to figure it out. If there is a place for everything, you can quickly see when anything is not in its place. The old adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” cannot be truer in Lean. Through a picture, a graph, a trouble light, process intelligence tools, and other visual techniques, you can quickly and easily understand information, respond to events and improve the process. (We cover more about visual management in Part IV.)

Annually, countless thousands of trees give their lives to become large reports that few people read — but not in Lean. Thick reports are waste. Because the purpose of reporting is to provide information for people to actually use, in Lean, you use a single-page format (also called A3 reporting, in a reference to the international paper size) to easily see the truly critical and necessary information, such as a description of the issue, actions, data, and resolution. This way, the reader can put their time into action, rather than digesting data.

Long-term journey

Lean does produce instant results; you see immediate improvement. In fact, you see improvement faster than almost any other way. But Lean is not a fad diet for your business. To sustain that improvement, you must be in the game for the long haul. Lean is a lifestyle change that requires diligence. If Lean were a race, it would be more like the tortoise, not the hare: steady incremental improvements over the long term. This is not to say that you don’t experience a burst of speed along some stretches; this will happen when you conduct multiple improvement workshops simultaneously (known as the kaizen blitz). Anyone with some data, analysis tools, and control charts can always improve something in the short term; the key to Lean is the sustainability and incorporation of changes into the normal daily business routine over the long term.

Simple is better: The KISS principle

Life has become so complex that you practically need an advanced degree to change the oil in your car or to program the TV remote. Does all this complexity actually add value? When everything is working well, it seems to — but when it isn’t, well, that’s a different story. Because everything has become so complex, it doesn’t always work so well.

The easier something is, the easier you can learn it, and the easier it is for you to deal with it when problems occur — whether that something is a product, a service, or the process that creates it. Simplicity is one of the beauties of Lean. It doesn’t mean that you don’t solve complex issues, but it does mean that you strive to find simple solutions to them. Lean improvements don’t necessarily cost a lot of money. If you can error-proof something equally well with a block of wood and duct tape versus a computer-controlled apparatus, Lean tells you to tend towards the wood-and-duct-tape solution. Consider the solution that’s quicker, faster, and cheaper, both in the short term and the long term.

Quality at the source

Have you ever put on a new pair of jeans and found an inspector tag? Does that add value to you, the customer? Do you feel like the pants have any greater level of quality because an inspector left a tag that you had to pull out of the pocket to throw away? “Certified by Inspector Number 12” was a slogan that the marketing gurus used to make people believe that the product they were buying was somehow better (or at least acceptable) because Inspector Number 12 was on the job. The reality is that by the time Inspector Number 12 sees the product, it’s too late: The quality is already there, or not.

You can’t inspect quality into a product — ever. Many companies use inspectors to try to catch defects before they’re released to the market, but the act of inspection doesn’t change the quality of what’s already been produced. People also use containment, which is the excuse to inspect while you keep producing suspect product. In Lean, you create a quality product at each step of the value stream. If defects occur, the product or service element doesn’t leave the current process step, either because the person doing the job caught the error or there was autonomation that detected the issue. Meanwhile, the next operator in the process may check key characteristics of a product. If they find an issue, they send the product back to the previous operation. The person who performed the transformational step owns the responsibility for the quality of his work. Now everyone is an “inspector,” and quality at the source becomes a reality.

Not all inspection is necessarily bad, but all inspection is, by definition, non-value added. Inspection does nothing to transform the product or service. Inspection is deemed necessary when the risk of the product or service advancing beyond that stage of the value stream will put the customer at risk or have a great financial impact; it could be a point of no return for repairs, for example. If you require separate inspection stations, be sure they follow a clearly defined, standardized work process.

Measurement systems: reinforcing Lean behaviors

People respond to how they’re measured. If your measurement system supports the Lean principles, you’ll reinforce Lean behaviors. Also, if your measurement system facilitates a change towards Lean, you’ll see the change happen.

One common example of a measurement system that does not support Lean is the traditional cost accounting system. Traditional accounting for equipment and direct labor actually encourages waste. Under such systems, equipment absorbs overhead, so supervisors run equipment to make their numbers look better, whether they need to produce or not. This leads to one of the seven forms of waste — overproduction — which we discuss in the “Muda, muda, muda” section, later in this chapter.

Additionally, cost-accounting environments overemphasize the impact of direct labor. When cost-accounting systems were originally established, labor made up the majority of actual costs; now direct labor can be a minority of the cost. Companies have purchased automated equipment to eliminate direct labor, only to find that they have the same number of bodies supporting the equipment as they used to have performing the work! The difference is that those bodies are now indirect labor, and, ironically, they’re usually more skilled and, therefore, working at a higher pay rate. However, the accounting system still sees this as a benefit because of the measurement system. Ouch!

In addition to changing business practices, successful Lean organizations know that they need the right measurement systems to reinforce Lean behaviors. One tool that these organizations use is a Balanced Scorecard (see Chapter 13). The Balanced Scorecard tracks aspects of the business beyond the traditional financial measures. Areas like safety, people, quality, delivery, innovation and cost are measured to show the overall health of the business and identify where the opportunities for improvement exist.

Learning lasts a lifetime

Learning happens thousands of times a day — every day — in a Lean organization. Learning and improving through observations, experiments, and mistakes is fundamental to kaizen. In Lean, after a lesson is learned, the knowledge is institutionalized via updated work standards. And then the cycle repeats: Observe, improve, institutionalize. Individuals learn; teams learn; collectively, the knowledge of the organization increases. Every instant of every day is the right time to learn and grow.

Waste Not, Want Not

As an individual, if you’ve ever tried to get in shape, you know that you have to change the way you diet, exercise, hydrate, and rest in order to have long-term success. In your diet, you have to take out the empty calories and highly processed foods that do not add nutritional value. When you start paying attention to what you put in your mouth, you realize how much garbage has been unconsciously passing your lips.

When you start on a Lean journey, one of the key ways to improve the health of the value stream is to eliminate waste. Like the empty calories of junk food, you’ll find that a lot of non-value-added activities have crept into the diet of your value stream. Waste in Lean is described by the three Ms of muda (waste), mura (unevenness), and muri (overburden). Muda is divided into seven forms of waste, which we cover in the following section.

Muda, muda, muda

Waste is all around you, every day and everywhere. You waste your time, waiting in line, waiting in traffic, or waiting because of poor service. In your home, you may have experienced walking into a room looking for something that wasn’t where it was supposed to be — wasted time and effort. In your kitchen, you may have had to throw out science experiments from your refrigerator — again, waste. Doing things over? That’s waste, too.

By now, you may be wondering what “waste” or muda exactly is and isn’t. Taiichi Ohno categorized waste into seven forms. These seven forms are: transport, waiting, overproduction, defects, inventory, motion, and excess processing. Table 2-1 provides a summary of the seven forms of waste.

Table 2-1 The Seven Forms of Waste

|

Form of Waste |

Also Known As |

Explanation |

|

Transport |

Conveyance |

Any movement of product or materials that is not otherwise required to perform value-added processing is waste. The more you move, the more opportunity you have for damage or injury. |

|

Waiting |

Waiting or delay |

Waiting in all forms is waste. Any time a worker’s hands are idle is a waste of that resource, whether due to shortages, unbalanced workloads, need for instructions, or by design. |

|

Overproduction |

Overproduction |

Producing more than your customer requires is waste. It causes other wastes like inventory costs, manpower and conveyance to deal with excess product, consumption of raw materials, installation of excess capacity, and so on. |

|

Defect |

Correction, repair, rejects |

Any process, product, or service that fails to meet specifications is waste. Any processing that does not transform the product or is not done right the first time is also waste. |

|

Inventory |

Inventory |

Inventory anywhere in the value stream is not adding value. You may need inventory to manage imbalance between demand and production, but it is still non-value-added. It ties up financial resources. It is at risk to damage, obsolescence, spoilage, and quality issues. It takes up floor space and other resources to manage and track it. In addition, large inventories can cover up other sins in the process like imbalances, equipment issues, or poor work practices. |

|

Motion |

Motion or movement |

Any movement of a person’s body that does not add value to the process is waste. This includes walking, bending, lifting, twisting, and reaching. It also includes any adjustments or alignments made before the product can be transformed. |

|

Extra processing |

Processing or overprocessing |

Any processing that does not add value to the product or is the result of inadequate technology, sensitive materials, or quality prevention is waste. Examples include in-process protective packaging, alignment processing like basting in garment manufacturing or the removal of sprues in castings and molded parts. |

You may be thinking that some of these wastes are truly beyond your control. Regulatory demands, accounting requirements, or natural events may be causing these. For this reason, muda is divided into two classifications:

![]() Type-1 muda includes actions that are non-value-added, but are for some other reason deemed necessary. These forms of waste usually cannot be eliminated immediately.

Type-1 muda includes actions that are non-value-added, but are for some other reason deemed necessary. These forms of waste usually cannot be eliminated immediately.

![]() Type-2 muda are those activities that are non-value-added and are also not necessary. These are the first targets for elimination.

Type-2 muda are those activities that are non-value-added and are also not necessary. These are the first targets for elimination.

All in the family

Beyond the general forms of muda are two other cousins of the waste family: mura and muri. As with the forms of muda, the goal is to eliminate these types of waste, too.

Mura (Unevenness)

Mura is variation in an operation — when activities don’t go smoothly or consistently. This is waste caused by variation in quality, cost, or delivery. Mura consists of all the resources that are wasted when quality cannot be predicted. This is the cost for things such as testing, inspection, containment, rework, returns, overtime, unscheduled travel to the customer, and potentially the cost of a lost customer. To understand and reduce variation, you can use statistical tools and methods, including Pareto charts and Design of Experiments (DOE). More on these in Part IV.

Muri (Overdoing)

Muri is the unnecessary or unreasonable overburdening of people, equipment, or systems by demands that exceed capacity. Muri is the Japanese word for unreasonable, impossible, or overdoing. From a Lean perspective, muri applies to how work and tasks are designed. One of the core tenets of Lean is respect for people. If a company is asking its people to repeatedly perform movements that are harmful, wasteful, or unnecessary, this means the company is not respecting the people and, therefore, is not respecting the foundation of Lean. You perform ergonomic evaluations of operations to identify movements that are either harmful or unnecessary.

In addition to physical overburdening, requiring people to work excessive hours is a form of muri. Excessive meetings, “cover your back” emails, and the demands of the global business environment all contribute to muri. And you’ll see muri manifested in employee turnover, medical leaves, system outages and downtime, and poor decision making.

Customers are always changing. Technology, markets, and demographics change your customers’ behavior continuously. Think about how differently people interact, work, produce, eat, play, and travel compared to 5, 10, or 20 years ago. Most industries and consumer markets have been in a constant state of reinvention since 2000. Events like the Internet boom, the housing bust, the emergence of social media, and various global economic crises have changed consumer habits significantly.

Customers are always changing. Technology, markets, and demographics change your customers’ behavior continuously. Think about how differently people interact, work, produce, eat, play, and travel compared to 5, 10, or 20 years ago. Most industries and consumer markets have been in a constant state of reinvention since 2000. Events like the Internet boom, the housing bust, the emergence of social media, and various global economic crises have changed consumer habits significantly.

Traditional sales and marketing practices need to be in step with the steady-state flow of the Lean enterprise. Sales incentives and seasonal campaigns, like inventory clearance sales or Independence Day sales, drive up demand and cause products to be sold at lower prices. This artificially bullwhips the supply chain. The concepts of level selling and steady-state pricing support a more effective enterprise.

Traditional sales and marketing practices need to be in step with the steady-state flow of the Lean enterprise. Sales incentives and seasonal campaigns, like inventory clearance sales or Independence Day sales, drive up demand and cause products to be sold at lower prices. This artificially bullwhips the supply chain. The concepts of level selling and steady-state pricing support a more effective enterprise.