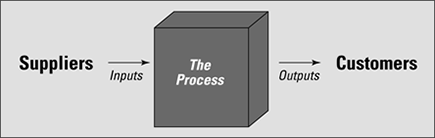

Figure 6-1: A SIPOC diagram.

Chapter 6

Seeing Value through the Eyes of the Customer

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding the concept of value

Understanding the concept of value

![]() Identifying what customers value

Identifying what customers value

![]() Differentiating customers and consumers

Differentiating customers and consumers

You may think the concept of value is pretty straightforward, but the reality is that everyone has their own perception of what constitutes value. What people value and how they value it changes with circumstance and time. But, as mutable as the criteria for defining value may be, Lean provides a framework for understanding what customers and consumers value, and then helping us understand how to provide that value in the most effective way. As you define what your customers value, you also define the very nature of your activities and actions: what you should be doing, how you should be doing it, and even if you should be doing it.

Consider this: When the coffee-shop barista writes your name on the cup for your double latte, is he “adding value” to your drink? When you check out at the grocery, is the full-service checkout “adding value” to your purchasing experience? When you fill out the form at the doctor’s office for your annual checkup, are you “adding value” to your health? Maybe — and maybe not. It all depends on how you define value.

Defining “value” is important because it forms the foundation upon which you build Lean processes to deliver that value and satisfy your customer. In this chapter, we provide the basic definition of value, and show you the Lean standard definition of value. You discover how to distinguish customers and consumers and learn ways to understand what they value.

What Is Value?

Simply stated, value is the worth placed upon something. That something can be goods, services, or both. The worth can be expressed in terms of money, an exchange, a utility, a merit, or even a principle or standard.

Who determines the value? Customers determine value. And there are billions of them — individuals, businesses, social groups, and other organizations.

Although Lean provides us a standard definition of value, what is more difficult to understand is what these customers deem worthy and then how to create, apply, measure, and translate their definition of value. What are the actions and activities that actually create value? How does a person or organization come to value a particular product or service? What determines how much a person is willing to “pay” for it — with their time, money, or other resources? In addition, how do they exchange value?

Value isn’t absolute — it doesn’t occur in isolation. Value is relative to such factors as location, place, time, timing, form, fit, function, integration, interactions, resources, markets, demand, and economics. But in all cases, value is defined by the customer.

The process of value creation — the act of developing and delivering a product or service that the customer desires and is willing to invest in having it — is usually lengthy and complicated.

Consider the complexity involved in the process of creating value in something that many people regularly take for granted: autonomous, personal mobility in the form of the automobile. In this case, value creation involves not just the design and assembly of the thousands of parts in a car, but also the highway system, the petroleum refining and distribution system, the maintenance and repair industry, the insurance industry, and the knowledge and conventions enforced in the millions of other drivers out there that you have to interact with in order to move about with some degree of certainty. Every driver antes up, in the form of sticker prices and insurance payments, gasoline and maintenance fees, highway and other taxes, greenhouse gases and environmental damage, personal risk, and, of course, lots and lots of time. Autonomous, personal mobility is an extremely high-value item, and each of the previously mentioned elements contributes a critical piece to that total value.

To Add Value or Not to Add Value, That Is the Question

Every activity in your organization either adds value or it doesn’t. In Lean, you analyze each activity in every process for its contribution to value, as defined by your customer. In the ideal state, every activity directly meets your customer’s criteria for value — and if it doesn’t, you don’t do it.

Makes you think, doesn’t it? Everyone and everything in the process doing only what creates customer value? Well, ideally that’s what Lean is all about!

Think about this principle in the context of what you do for your customers, whoever they may be. How much of all the time, people, resources, capital, space, and energy consumed around you and by you is directly creating value for your customers? Now put on the other hat, and think about it from the customers’ point of view. When you’re paying for a product or service — with your valuable time, money, and effort — how much are you spending to get what you really want . . . and only what you really want?

In this section, we fill you in on Lean’s strict definition for value-added and non-value-added. You will understand non-value added according to the three Ms — muda, mura, and muri. Some activities in your process do not add value according to the customer’s definition, but they are unfortunately necessary for your processes to function. We will tell you what to do in those cases, too.

Defining value-added

In Lean, always define value from the customer’s viewpoint. The customer is the one — and only one — who defines the value of the output of a process. For an activity to be value added, you must meet all three precise criteria:

![]() The customer must be willing to pay for the activity.

The customer must be willing to pay for the activity.

![]() The activity must transform the product or service in some way.

The activity must transform the product or service in some way.

![]() The activity must be done correctly the first time.

The activity must be done correctly the first time.

This strict definition applies to everything. To add value in a process, all actions, activities, processes, persons, organizations, systems, pieces of equipment, and any other resources committed to the process must meet all three criteria.

You can easily spot value-added activity:

![]() At the carwash, it’s when someone actually washes the car.

At the carwash, it’s when someone actually washes the car.

![]() At the hospital, it is when the patient receives treatment.

At the hospital, it is when the patient receives treatment.

![]() On the assembly floor, it’s when someone is actually putting parts together.

On the assembly floor, it’s when someone is actually putting parts together.

In each of these cases, it’s clearly what the customer is paying for; it’s transforming the product or providing the primary service; and as long as it’s being done correctly the first time, it is by-definition contributing directly to customer value (that is, it’s value-added).

Defining non-value-added

In Lean, if an activity does not meet all three value-added criteria (see the preceding section), then it is deemed officially to be non-value-added. Either the customer isn’t willing to pay for it, or the activity hasn’t transformed the product or service in any measurable way, or the activity wasn’t done correctly the first time. In other words, from the customer’s perspective it’s wasted time or effort.

At the carwash, it’s the order-taker, the car-mover, the cashier, the queuing time, the excess water, and the customer waiting lounge. At the hospital, it’s the check-in time, the wait time, filling out forms, inconclusive tests, and yummy hospital food. On the assembly floor, it’s the parts bins, the travel time, the setup time, the inspections and testing, the conveyors, the supervisors, the bad-parts reject basket.

In each of these cases, the item or person wasn’t something the customer wanted to pay for or the activity didn’t directly transform the product or service, or something wasn’t done correctly.

Wait a minute, you say: Some of those things are important, even necessary! Customers have to pay for what it takes to provide a product or service. Employees need supervisors. Forms convey important information. Customer lounges keep people happy — you can’t just make them wait outside, right? And bad components have to be removed — after all, isn’t it a good thing when you catch a failure and don’t ship a bad product to the customer?

Sorry to burst your bubble, but if the activity in question doesn’t meet all three criteria, it’s just not adding customer value. The customer lounge is nice, but it doesn’t get your car washed better. Filling out forms may get you admitted to the hospital, but it doesn’t directly contribute to your treatment. The reject basket means you caught the failures, but they’re a living example of something that wasn’t done correctly the first time. None of this means that you might not want or even need to do these things based on your existing process model, but it does mean that those activities are not directly adding value for the customer.

In Lean, non-value-added activities are further described by the three Ms — muda, mura, and muri:

![]() Muda (waste): Muda is an activity that consumes resources without creating value for the customer. (We define the seven standard forms of waste in detail in Chapter 2.) There are two types of muda:

Muda (waste): Muda is an activity that consumes resources without creating value for the customer. (We define the seven standard forms of waste in detail in Chapter 2.) There are two types of muda:

• Type-1 muda includes actions that are non-value-added, but that are for some other reason deemed necessary. These forms of waste usually cannot be eliminated immediately.

• Type-2 muda are those activities that are non-value-added and are unnecessary. These activities are the first targets for elimination.

![]() Mura (unevenness): Mura is waste caused by variation in quality, cost, or delivery. When activities don’t go smoothly or consistently, mura is the result. Mura consists of all the resources that are wasted when quality cannot be predicted, such as the cost of testing, inspection, containment, rework, returns, overtime, and unscheduled travel to the customer. You apply variation reduction techniques to eliminate mura.

Mura (unevenness): Mura is waste caused by variation in quality, cost, or delivery. When activities don’t go smoothly or consistently, mura is the result. Mura consists of all the resources that are wasted when quality cannot be predicted, such as the cost of testing, inspection, containment, rework, returns, overtime, and unscheduled travel to the customer. You apply variation reduction techniques to eliminate mura.

![]() Muri (overdoing): Muri is the unnecessary or unreasonable overburdening of people, equipment, or systems by demands that exceed capacity. From a Lean perspective, muri applies to the design of work and tasks. For example, tasks with muri have by movements that are harmful, wasteful, or unnecessary. You perform ergonomic evaluations and detailed job analysis of operations to eliminate movements that are either harmful or unnecessary.

Muri (overdoing): Muri is the unnecessary or unreasonable overburdening of people, equipment, or systems by demands that exceed capacity. From a Lean perspective, muri applies to the design of work and tasks. For example, tasks with muri have by movements that are harmful, wasteful, or unnecessary. You perform ergonomic evaluations and detailed job analysis of operations to eliminate movements that are either harmful or unnecessary.

When non-value-added seems like value-added

By their very nature, processes are full of waste that masquerades as value creation. Many activities may seem as though they’re necessary or value-added, but upon closer examination, and through the eyes of the customer —according to the three criteria listed in the “Defining value-added” section earlier in this chapter — they’re not.

Muda, particularly type-1 muda (see the preceding section), is usually created because of current facility or technology limitations, government regulations, or unchallenged company business practices. Oftentimes, muda is so insidious that the organization is blind to it. Identifying muda is particularly difficult when muda is programmed into computer systems.

Seeking out and eliminating muda takes effort — it requires someone to challenge the status quo. Sometimes people don’t think they have the time or energy to do that level of work. Sometimes they don’t feel like they have the tools or authority to change the current state. Sometimes they don’t know where to begin. And sometimes, they just don’t want to change. Yet the fact of the matter is that when you put in the effort to identify the muda, you will find a gold mine of opportunity.

Common examples of type 1-muda include the following:

![]() Bureaucracy, such as forms, reports, traditions, and approvals

Bureaucracy, such as forms, reports, traditions, and approvals

![]() Administrative activities, such as supervision, accounting, and legal

Administrative activities, such as supervision, accounting, and legal

![]() Product support, such as product testing, critical inspection, and transportation

Product support, such as product testing, critical inspection, and transportation

You may insist, “These activities are necessary for the business!” And you may even be right — maybe they are necessary. But whether they’re necessary or not, it doesn’t change the fact that they are non-value-added. Here are some examples:

![]() The admission process at a hospital: Surely it must be value-added. After all, how else can you get in to the hospital to be treated — what could be more value-added than that? Not so. Nothing in the admission process directly contributes to the treatment of a patient; therefore, it is not adding customer value.

The admission process at a hospital: Surely it must be value-added. After all, how else can you get in to the hospital to be treated — what could be more value-added than that? Not so. Nothing in the admission process directly contributes to the treatment of a patient; therefore, it is not adding customer value.

![]() The in-line inspection station in the automobile manufacturing industry: You need to ensure operations are performed correctly; you must protect your customer. Although this is may be true, you cannot transform a product through inspection, you can only mitigate risk. The most well-choreographed inspection station, while seemingly necessary, is always non-value added.

The in-line inspection station in the automobile manufacturing industry: You need to ensure operations are performed correctly; you must protect your customer. Although this is may be true, you cannot transform a product through inspection, you can only mitigate risk. The most well-choreographed inspection station, while seemingly necessary, is always non-value added.

![]() Staying late and pushing extra hard to get a job done and meet a deadline: The job has to get done, and people will rise to the occasion, right? Yes, but consider the cost. Not only do people tend to make more mistakes when they drive too hard without rest, but burned-out people leave and take critical knowledge and experience with them. On occasion, working in this manner may seem necessary, but no matter how you look at it, it’s a waste.

Staying late and pushing extra hard to get a job done and meet a deadline: The job has to get done, and people will rise to the occasion, right? Yes, but consider the cost. Not only do people tend to make more mistakes when they drive too hard without rest, but burned-out people leave and take critical knowledge and experience with them. On occasion, working in this manner may seem necessary, but no matter how you look at it, it’s a waste.

Understanding How the Customer Defines Value

Who is this elusive customer — the one who defines value? If you’re like most people, you’re thinking it’s the person at the retail end of the line — the one who buys the product or service, who walks into a store, gets out his wallet, pays for something, and leaves with it. Actually, that person is a special form of customer known as the consumer; we cover the consumer in the “Understanding How the Consumer Defines Value” section, later in this chapter.

The customer, as far as Lean is concerned, is the person or entity who is the recipient of the product or service you produce. For many, the customer is another business. For others, the customer is someone inside their own business. Sometimes the customer is a specific individual; other times, the customer is a group or team. In any case, the customer is the one who places the value on your output.

Uncovering the elusive customer

The world has grown so complicated that sometimes it’s difficult to determine just who anybody’s customer really is. So many functions, supply chains, outsourced providers, contract distributors, and channels are part of the mix. In the Lean world, this question — “Who is your customer?” — is fundamental because the customer is the one who matters. The customer is the only one who truly defines the value of what you produce.

In Figure 6-1, we show you a SIPOC (suppliers, inputs, process, outputs, and customers) diagram that lists the suppliers and inputs to a process on the one side, and the outputs and customers on the other. Considering the process itself as a black box for the moment, focus on what outputs you produce and who receives them. This recipient is the elusive customer you’re looking for.The SIPOC diagram is a standard tool in process management that helps identify and characterize these key driving influences on a process.

Every process — no matter how large-scale and all-encompassing, or small and focused — has a customer or customers. Large-scale processes, such as order entry or production, have a broad spectrum of many types of customers. In small processes, such as screen assembly for the latest mobile phone or the daily setup of a jewelry department in retail, the customer is much more narrowly and specifically defined. But in every case and at every level in any organization or endeavor, processes have customers.

![]() When you’re improving a small process within the overall process, recognize its role in the larger scheme of things. Many sub-processes — each with their own customers — make up the larger process of creating the total product or facilitating a complete service.

When you’re improving a small process within the overall process, recognize its role in the larger scheme of things. Many sub-processes — each with their own customers — make up the larger process of creating the total product or facilitating a complete service.

![]() Your process may produce outputs for multiple customers. Every customer has their unique characteristics, and you’ll regularly need to adjust your process according to requirements, attributes, and situations for each one.

Your process may produce outputs for multiple customers. Every customer has their unique characteristics, and you’ll regularly need to adjust your process according to requirements, attributes, and situations for each one.

![]() Recognize how your process output serves the end consumer. If your process does not directly supply the consumer, then your customer is a middleman. Your direct customer may be adding, filtering, interpreting or changing how the end consumer defines value. Your direct customer has different motivations and needs from the consumer. Make sure that you are meeting your direct customer’s needs, but don’t lose sight of the consumer’s expectations and definition of value.

Recognize how your process output serves the end consumer. If your process does not directly supply the consumer, then your customer is a middleman. Your direct customer may be adding, filtering, interpreting or changing how the end consumer defines value. Your direct customer has different motivations and needs from the consumer. Make sure that you are meeting your direct customer’s needs, but don’t lose sight of the consumer’s expectations and definition of value.

![]() Don’t become distracted by stakeholders. A stakeholder is someone with a vested interest elsewhere in the greater enterprise. Stakeholders may include managers, board members, stockholders, employees, suppliers, family members of employees, retirees, government, or the community. Stakeholders are important, but they are not the customer. Stakeholders have an interest in company performance or results. When a business is distracted by the stakeholders, it may lose the focus on the process and take short-term actions that will actually increase mura.

Don’t become distracted by stakeholders. A stakeholder is someone with a vested interest elsewhere in the greater enterprise. Stakeholders may include managers, board members, stockholders, employees, suppliers, family members of employees, retirees, government, or the community. Stakeholders are important, but they are not the customer. Stakeholders have an interest in company performance or results. When a business is distracted by the stakeholders, it may lose the focus on the process and take short-term actions that will actually increase mura.

Considering customer value

The customer is the purchaser of your goods and services, and they are the recipient of the outputs from your process. The customer has options, so why would they choose the outputs from your process? What goes into a customer’s purchase decision? And how does the customer determine what they’re going to pay?

The answers to these questions come down to value. The customer will choose your option when they believe it represents the best overall value for them. The customer has many requirements and decision criteria, and their methods of assigning value may be formal or informal, but ultimately they will place a worth on process and outputs and will select yours when they believe the outputs and the process best fulfill their requirements.

Understanding customer satisfaction

Because the customer assigns value based on the degree to which the process outputs fulfill their requirements, this means that the greater the fulfillment of requirements, the higher the customer’s satisfaction, and therefore the greater the customer’s attributed value.

Not all customer requirements are created equal. Some requirements are extremely important must-haves, other requirements are nice-to-haves, and still other requirements fall somewhere in the middle. How the fulfillment of these different requirements translates to customer satisfaction is not always obvious. Don’t worry — in this section, we spell it all out.

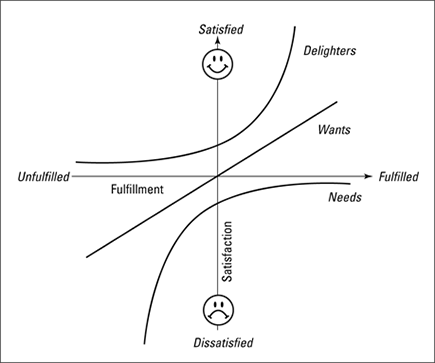

In the 1980s, Japanese professor Noriaki Kano developed a visual way to understand customer requirements (see Figure 6-2). This model is a graphical plot of fulfillment versus satisfaction. What Kano recognized is that customer requirements naturally come in three flavors, and the extent to which a process fulfills each type of requirement directly affects the level of customer satisfaction and perceived value.

Figure 6-2: Using Kano modeling to classify customer requirements.

![]() Needs: Needs are fundamental — they’re absolute requirements. You must fulfill the needs of your customer. If your customer has unfulfilled needs, that very quickly translates to complete dissatisfaction. However, at best, fulfilling your customer’s needs results in neutral satisfaction. In other words, meeting your customer’s needs is a thankless job, but failing to meet your customer’s needs is disastrous.

Needs: Needs are fundamental — they’re absolute requirements. You must fulfill the needs of your customer. If your customer has unfulfilled needs, that very quickly translates to complete dissatisfaction. However, at best, fulfilling your customer’s needs results in neutral satisfaction. In other words, meeting your customer’s needs is a thankless job, but failing to meet your customer’s needs is disastrous.

![]() Wants: Wants are expectations. If you don’t fulfill your customer’s wants, the customer will be dissatisfied; if you do fulfill your customer’s wants, the customer will be satisfied. The relationship is linear: No lack of fulfillment of wants will ever create the dissatisfaction that unmet needs will, and likewise no degree of fulfillment of wants will ever have the satisfaction potential of the third type of requirement — the delighters.

Wants: Wants are expectations. If you don’t fulfill your customer’s wants, the customer will be dissatisfied; if you do fulfill your customer’s wants, the customer will be satisfied. The relationship is linear: No lack of fulfillment of wants will ever create the dissatisfaction that unmet needs will, and likewise no degree of fulfillment of wants will ever have the satisfaction potential of the third type of requirement — the delighters.

![]() Delighters: Delighters are pure upside. No one really expects them, so there’s no penalty if they’re missing. But the level of customer satisfaction increases exponentially if the process fulfills these most whimsical of requirements.

Delighters: Delighters are pure upside. No one really expects them, so there’s no penalty if they’re missing. But the level of customer satisfaction increases exponentially if the process fulfills these most whimsical of requirements.

Take a moment to ponder the application of the Kano model to your business or organization. Of the many requirements you chase and manage, which fall into each of the three categories? How well do you fulfill them? How satisfied are your customers?

Breaking down customer requirements

Fulfilling the customer’s wants, needs, and delighters is the path to customer satisfaction. Kano modeling and Quality Function Deployment (QFD; this is covered in Chapter 10) are two tools that you can use to capture and understand customer requirements.

After you identify your customer’s requirements, you can analyze how effectively you’re satisfying those requirements. When you understand how effective you are, then can you optimize value creation, ensuring you meet all three conditions of value-added with your products, processes, or services.

To create a solution and fulfill your customer’s requirements, first translate them into product or service specifications. Start by documenting these specifications at the highest level, known as the top level, the system level, or the A level; then, successively expand the specifications into subsystems or sub-processes, each of which fulfills a specific role in achieving the overall objective defined by the top-level specification. Within each of these levels, categorize the specifications into the following “spec-types”:

![]() Form and fit: What are the shapes and sizes, the constraints and the tolerances of the way the product or service (or components thereof) must be designed, must align, or must interact?

Form and fit: What are the shapes and sizes, the constraints and the tolerances of the way the product or service (or components thereof) must be designed, must align, or must interact?

![]() Functionality: What are all the things that the product or service must do? How must it do them? How uniquely? The specifications are usually described through a set of action verbs, but they may also describe aesthetics and other physical or operational attributes.

Functionality: What are all the things that the product or service must do? How must it do them? How uniquely? The specifications are usually described through a set of action verbs, but they may also describe aesthetics and other physical or operational attributes.

![]() Maintainability: What are the support and maintenance requirements? Is the customer or consumer required or able to maintain it, or portions of it, themselves? How will it be supported?

Maintainability: What are the support and maintenance requirements? Is the customer or consumer required or able to maintain it, or portions of it, themselves? How will it be supported?

![]() Perception: How are you perceived in the market? What is your brand identity? What has been the customer’s past experience with your organization? Have you had any bad press that may affect a purchasing decision? What is the experience you want to create for the customer?

Perception: How are you perceived in the market? What is your brand identity? What has been the customer’s past experience with your organization? Have you had any bad press that may affect a purchasing decision? What is the experience you want to create for the customer?

![]() Performance: How quickly, how often, or for how long must the product or service perform its functions?

Performance: How quickly, how often, or for how long must the product or service perform its functions?

![]() Pricing model: What is the price that the customer will pay for the product or service? Is the price dynamic (will it or should it change over time)? What is the desired profit margin? What is the total cost picture?

Pricing model: What is the price that the customer will pay for the product or service? Is the price dynamic (will it or should it change over time)? What is the desired profit margin? What is the total cost picture?

![]() Purchase: What are the various purchasing models and terms by which the customer will buy? What should the purchasing experience be?

Purchase: What are the various purchasing models and terms by which the customer will buy? What should the purchasing experience be?

![]() Reliability: With what levels of reliability and dependability must the product or service perform its functions? What is the pedigree and what experience do you bring to ensure that reliability?

Reliability: With what levels of reliability and dependability must the product or service perform its functions? What is the pedigree and what experience do you bring to ensure that reliability?

![]() Safety: Are there safety aspects to the product or service — as related to the suppliers, consumers, maintenance groups, or even the general public?

Safety: Are there safety aspects to the product or service — as related to the suppliers, consumers, maintenance groups, or even the general public?

![]() Scalability: If the customer wants more, how readily should they be able to have more? Do any of the other requirements elements change with scalability?

Scalability: If the customer wants more, how readily should they be able to have more? Do any of the other requirements elements change with scalability?

![]() Security: Security concerns are a separate requirements element. Could the product or service pose a security risk in any way, either directly or indirectly?

Security: Security concerns are a separate requirements element. Could the product or service pose a security risk in any way, either directly or indirectly?

These categories of requirements apply during any phase of the product or service life cycle; they apply to the core processes of design, development, delivery, and service, as well as support processes, including sales, finance, legal, marketing, human resources, information technology, and facilities. Every process must reflect these elements to ensure the product or service provided will properly fulfill the customer’s needs, wants, and desires. These categories apply not just to the end consumer, but also to your immediate customer and each successive customer in the chain. No matter where your process sits in the big picture, these categories of requirements apply to you!

Remember that what your customer values is not static. Customer interests and satisfaction change over time. The Kano model has a “downward migration”: over time, delighters become wants, and wants become needs. Having processes that connect you with your customers will help you stay agile and change with their changing demands.

Understanding How the Consumer Defines Value

The ultimate customer is the consumer. The consumer is defined as “one who obtains goods and services for his own use,” rather than for resale or use in producing another product or service. Consumers are the catalyst in the value chain; their buying action triggers the flow of activities on the part of the many product and service providers whose contributions ultimately fulfill the consumers’ requirements and values.

As such, the consumer holds a uniquely important customer position, and it’s incumbent on you — regardless of your position in the value chain — to be aware of consumer motivation and behavior. In most cases, you work directly for your immediate customer because they specify your requirements and receive your outputs; however, consumer actions will ripple through the chain to affect you, so you must also understand how the consumer defines value.

Recognize, too, that although the entire stream of activity is ultimately oriented toward satisfying the consumer, the consumer’s requirements and values do not necessarily align with the processes and agendas of all the many value-stream players providing those goods and services. Your direct customer will likely represent the consumer’s needs to you differently than the consumer would, so you must be in a position to understand and balance your direct customer’s requirements with those of the end consumer.

Because Lean processes are customer focused, they respond to the requirements of the customer and refine their processes accordingly. Although each successive process may have a unique set of customer requirements, the starting point is with the consumer, because the consumer is the first point of requirements definition. The consumer is the first to assign value and first to vote with their wallet. The consumer kicks off the whole process.

Responding to the consumer

Organizations of all types strive to understand and anticipate the consumer. The better an organization can predict consumer behavior; the more effectively it can fulfill the consumer’s needs, wants, and delighters (see “Understanding customer satisfaction,” earlier in this chapter). In some cases, you need to understand broad consumer behavior and then produce products in volume for the general consumer market. In other cases, you have to maintain the capacity to produce a product or deliver a service on demand. In most cases, it’s a mix.

Most companies aren’t fluid or flexible enough to wait for a customer-demand event to act across their entire supply chain, but many such demand build-to-order models exist at the direct consumer end of the market. Can you imagine a world where all companies operated that way? Can you think of a few who currently do? Here are a few:

![]() Most fast-food restaurants now build your meal to order. They have the basic ingredients on hand (based on past consumer behavior), and when you order, they prepare your meal to your specifications and deliver it to you in a matter of minutes.

Most fast-food restaurants now build your meal to order. They have the basic ingredients on hand (based on past consumer behavior), and when you order, they prepare your meal to your specifications and deliver it to you in a matter of minutes.

![]() Eyeglasses used to take days or weeks to arrive, but now some companies have moved the lab into the retail location. Your glasses are now ready in an hour.

Eyeglasses used to take days or weeks to arrive, but now some companies have moved the lab into the retail location. Your glasses are now ready in an hour.

![]() Business consultants wait for the call and then configure their solutions based on the requirements. Consultants are extremely adept at forging new solutions in near real-time, based on the application of their latest knowledge, and quickly preparing a new solution for the client.

Business consultants wait for the call and then configure their solutions based on the requirements. Consultants are extremely adept at forging new solutions in near real-time, based on the application of their latest knowledge, and quickly preparing a new solution for the client.

In these types of applications, the value stream is closely connected to the needs of the consumer. For example, the disk-drive manufacturer who supplies hard drives to the computer assembler follows the consumer demand market very closely. Similarly, food suppliers to restaurants know what the diner is requesting — organic, gluten-free, and low-carb are recent trends in mainstream dining.

Consumers further influence the market through the unique spin they have on requirements. In addition to the Kano profiles and formalized requirements flow, consumers exhibit specific behaviors and styles. These styles set the stage for how the entire value stream — and all the intermediate processes and customers — will act. Consumers largely fall into one of eight behavior style types, as defined by Sproles and Kendall’s Consumer Style Inventory:

![]() Perfectionism; high-quality conscious

Perfectionism; high-quality conscious

![]() Brand conscious

Brand conscious

![]() Novelty-fashion conscious

Novelty-fashion conscious

![]() Recreational, hedonistic shopping conscious

Recreational, hedonistic shopping conscious

![]() Price and “value-for-the-money” shopping conscious

Price and “value-for-the-money” shopping conscious

![]() Impulsiveness

Impulsiveness

![]() Confusion over choice of brands, stores, and consumer information

Confusion over choice of brands, stores, and consumer information

![]() Habitual, brand-loyal orientation toward consumption

Habitual, brand-loyal orientation toward consumption

Consider the eyewear shop that promises to deliver your glasses in an hour. What must that store do to live up to its promise? It must have all the materials, processes, and services on site to fulfill the needs of their customers and market. This includes having a sufficient variety of styles on hand to appeal to the variety of consumer interests — they need the designer section, the hip-and-trendy section, and the value section. They must also maintain the right level of inventory of frames and the lens blanks to go with them. They must maintain their equipment locally. They must have trained technicians on site. And they must be conveniently located for consumer access (in shopping malls). All these elements come together to provide the consumer with glasses in an hour.

Online purchasing and mobile Internet devices have changed consumer behavior. Consumers see value in going online, both to check out and to check you out. They relish having the tools at their fingertips to research and make more educated purchases. More than ever, they know what they want, they’re empowered by knowing how to get it, and they’ll search until they find it. This connectivity is causing companies to become increasingly innovative in the ways they reach their existing markets, as well as penetrate new ones. Some consumers will do the research online, but still want to talk to a human or buy from a store. Other consumers are content to do everything online — from researching to buying to returns. Lean practitioners recognize these new channels represent different value paths with customers and consumers, and that processes must adapt.

Understanding what consumers value

Consumers are customers with a twist. In addition to the behaviors that business customers exhibit across the value chain (the so-called business-to-business, or B2B, group), the consumers have unique requirements and demands. The business-to-consumer relationship (B2C) must interpret these demands and properly manage them — directly or indirectly — back upstream to all the suppliers.

Understanding the distribution of styles in your market is a key step to understanding what your consumers value. Depending on the industry, the product or service, the magnitude of the purchase and other factors, the relationship with consumers through the pre- and post-buying phases ultimately determines the degree of your success. Table 6-1 provides a list of consumer interests. For each interest, the consumer has demands, which place constraints on the processes that support them.

Table 6-1 Mapping Consumer Demands to Process Constraints

|

Interest |

Consumer Demands |

Lean Process Constraints |

|

Final Purchase Price |

Price-point sensitivity Total system or solution price |

Price pressures are distributed across all providers, each with their own cost and profit profiles. |

|

Quality |

Initial quality Safety/Security Durability Ease of maintenance |

Each provider must deliver to quality levels that combine to support the final end-item quality, create no safety hazards and are easy to maintain. |

|

Delivery |

Fast delivery Delivery on demand |

Every component must be available exactly when required by the processes that build the final consumer product or service. The delivery system must be able to meet the consumer’s delivery expectations. |

|

Service |

Immediate assistance Friendly service Reasonable terms |

Services must be provided at each level — or combined to provide effective consumer service. Timing and completeness of response are critical. |

|

Purchase Terms |

Monthly payments Favorable rates |

The consumer’s financing and payment terms affect everyone in the supply chain. |

|

Image |

Fashion, trendiness Newness, novelty Premium value |

Everything is affected — from design to manufacture to delivery and terms — for all component products and services. |

|

Convenience |

Open 24/7/365 Brand preference |

You must produce and deliver in ways that the consumer values most. |

|

Returns |

Unconditional returnability |

Reverse logistics processes must meet the consumer’s needs — understanding the circumstances of responding to satisfaction issues. |

|

Experience |

Environment and amenities |

Make the customer experience inviting and delightful. Understand what delighters can be added to perceived customer value with minimal impact on the operating cost. |

In simple terms, consumers want what they want, when they want it, at the price they’re willing to pay for it, and if something goes wrong, they want accurate and friendly assistance or the ability to return it easily. These demands place tremendous pressure and constraints on each provider of the goods and services that combine to provide that end item to the consumer.

Companies are just now beginning to include the interface between the company and consumer as part of their Lean efforts. Processes from the point the consumer purchases through customer service and technical support are new frontiers for Lean implementation. These processes can make or break your relationship with consumers (not to mention their friends and families!), and are a new spring of improvement possibilities. Eliminating waste and creating a positive, value-added customer experience will increase competitive edge.

Think about how much the morning cup of coffee has changed. Starbucks created the coffee experience — any time of day, people could meet up, work, or just relax in one of their shops. Customers were willing to pay a premium price for a cup of java to delight in the experience. Now, people expect a Starbucks on every corner; they expect their exotic drink quickly, made-to-order, and consistently. The former delighter has now become a necessity. Food chains like McDonalds and retailers like Target are incorporating the “coffee experience” into their stores with expanded coffee menus and free wi-fi.

Think also about how personal computing has changed. Not too long ago the standard was a desktop system; then it was the laptop. Then Apple introduced the iPad — a light, ultra-portable, powerful, and sexy computing experience — and the game changed again. Established industry players are feeling the challenge to compete with these new customer expectations.

Beginning with theY2K phenomenon, many companies outsourced call center work to other countries. Some companies have had to rethink their approach, because consumers struggled to communicate with the people on the other end of the line. When the consumer was already frustrated, this made matters worse. True costs increased, because the companies alienated their customer base. The companies failed to understand fully what the consumer values.

The cycle of value means that, in any endeavor — large or small — all of the activities, actions, and steps involved must lead to an end-result that has value for whoever is consuming it. And they must easily perceive that value, be able to readily quantify it, and willingly exchange for it. Meanwhile, the providers must deliver that value for some net benefit or profit.

The cycle of value means that, in any endeavor — large or small — all of the activities, actions, and steps involved must lead to an end-result that has value for whoever is consuming it. And they must easily perceive that value, be able to readily quantify it, and willingly exchange for it. Meanwhile, the providers must deliver that value for some net benefit or profit.