LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- 1 Review the full disclosure principle and describe implementation problems.

- 2 Explain the use of notes in financial statement preparation.

- 3 Discuss the disclosure requirements for related-party transactions, subsequent events, and major business segments.

- 4 Describe the accounting problems associated with interim reporting.

- 5 Identify the major disclosures in the auditor's report.

- 6 Understand management's responsibilities for financials.

- 7 Identify issues related to financial forecasts and projections.

- 8 Describe the profession's response to fraudulent financial reporting.

We Need Better, Not More

As you have learned in your study of this textbook, financial statements contain a wealth of useful information to help investors and creditors assess the amounts, timing, and uncertainty of future cash flows. In addition, the usefulness of accounting reports is enhanced when companies provide note disclosures to help statement readers understand how IFRS was applied to transactions. These additional disclosures help readers understand both the judgments that management made and how those judgments affected the amount reported in the financial statements. Some users, however, feel we need to go even further.

The IASB has heard these demands for improved financial reporting and disclosure and is responding. It organized a Discussion Forum as well as conducted a survey of preparers and users to get input on the effectiveness of reporting and disclosure in financial statements. The survey asked several questions about whether there is a disclosure problem and where in the annual report the problem arises. The survey focused on three potential areas: (1) not enough relevant information, (2) too much irrelevant information, and (3) poor communication of disclosures. The following graphic summarizes the feedback.

As indicated, preparers viewed the disclosure problem as primarily one of information overload; that is, they are being required to provide too much data. Users, on the other hand, complained that some of the information they get is poorly communicated and not that relevant. The message that emerged from the Discussion Forum was similar. Specifically, increases in the volume of financial disclosures has resulted in a perceived reduction in their quality and usefulness. More importantly, there was broad consensus that collective action was required in order for improvements to be made.

As a result, the IASB is taking action in three main areas:

- Amendments to IAS 1. The IASB will make amendments to IAS 1 (“Presentation of Financial Statements”) to address perceived impediments to preparers exercising their judgment in presenting their financial reports.

- Materiality. The IASB will seek to develop educational material on materiality with input from an advisory group.

- Separate project on disclosure. The IASB will consider as part of its research agenda the broader challenges associated with disclosure effectiveness.

Hans Hoogervorst, chairman of the IASB, summarized the IASB's response as follows: “It is undoubtedly true that we and others can improve our [disclosure] requirements. However, material improvements will require behavioural change to ensure that financial statements are regarded as tools of communication rather than compliance. That means addressing the root causes of why preparers may err on the side of caution and ‘kitchen-sink’ their disclosures.” The bottom line: We need better, not necessarily more, disclosure.

Source: “Discussion Forum—Financial Reporting Disclosure,” Feedback Statement (London, U.K.: IASB, May 2013), http://www.ifrs.org/Current-Projects/IASB-Projects/Disclosure-Initiative/Pages/Disclosure-Initiative.aspx. See also “Disclosure Initiative: Proposed Amendments to IAS 1,” Exposure Draft ED/2014/1 (London, U.K.: IASB, March 2014).

PREVIEW OF CHAPTER 24

As the opening story indicates, investors and other interested parties are concerned about the quality of information for all aspects of financial reporting—the financial statements, the notes, the president's letter, and management commentary. In this chapter, we cover the full disclosure principle in more detail and examine disclosures that must accompany financial statements so that they are not misleading. The content and organization of this chapter are as follows.

FULL DISCLOSURE PRINCIPLE

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Review the full disclosure principle and describe implementation problems.

The IASB Conceptual Framework notes that while some useful information is best provided in the financial statements, some is best provided by other means. For example, net income and cash flows are readily available in financial statements, but investors might do better to look at comparisons to other companies in the same industry, found in news articles or brokerage house reports.

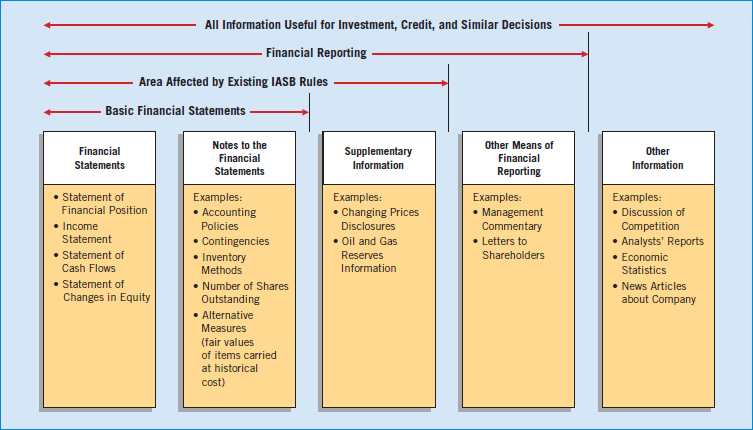

IASB rules directly affect financial statements, notes to the financial statements, and supplementary information. These accounting standards provide guidance on recognition and measurement of amounts reported in the financial statements. However, due to the many judgments involved in applying IFRS, note disclosures provide important information about the application of IFRS. Supplementary information includes items such as disclosures about the risks and uncertainties, resources and obligations not recognized in the statement of financial position (such as mineral reserves), and information about geographical and industry segments. Other types of information found in the annual report, such as management commentary and the letters to shareholders, are not subject to IASB rules. [1] Illustration 24-1 indicates the various types of financial information.

![]() See the Authoritative Literature section (pages 1301–1302).

See the Authoritative Literature section (pages 1301–1302).

ILLUSTRATION 24-1

Types of Financial Information

As Chapter 2 indicated, the profession has adopted a full disclosure principle. The full disclosure principle calls for financial reporting of any financial facts significant enough to influence the judgment of an informed reader. In some situations, the benefits of disclosure may be apparent but the costs uncertain. In other instances, the costs may be certain but the benefits of disclosure not as apparent.

For example, the IASB requires companies to provide expanded disclosures about their contractual obligations. In light of the accounting frauds at companies like Parmalat (ITA), the benefits of these expanded disclosures seem fairly obvious to the investing public. While no one has documented the exact costs of disclosure in these situations, they would appear to be relatively small.

On the other hand, the cost of disclosure can be substantial in some cases and the benefits difficult to assess. For example, at one time the financial press reported that if segment reporting were adopted, a company like Fruehauf (USA) would have had to increase its accounting staff 50 percent, from 300 to 450 individuals. In this case, the cost of disclosure can be measured, but the benefits are less well defined.

Some even argue that the reporting requirements are so detailed and substantial that users have a difficult time absorbing the information. These critics charge the profession with engaging in information overload.

Financial disasters at Mahindra Satyam (IND) and Société Générale (FRA) highlight the difficulty of implementing the full disclosure principle. They raise the issue of why investors were not aware of potential problems: Was the information these companies presented not comprehensible? Was it buried? Was it too technical? Was it properly presented and fully disclosed as of the financial statement date, but the situation later deteriorated? Or was it simply not there? In the following sections, we describe the elements of high-quality disclosure that will enable companies to avoid these disclosure pitfalls.

Increase in Reporting Requirements

Disclosure requirements have increased substantially. One survey showed that the size of many companies' annual reports is growing in response to demands for increased transparency. For example, annual report page counts ranged from 92 pages for Wm Morrison Supermarkets plc (GBR) up to a whopping 268 pages in Telefónica's (ESP) annual report. This result is not surprising; as illustrated throughout this textbook, the IASB has issued many pronouncements in the last 10 years that have substantial disclosure provisions.

The reasons for this increase in disclosure requirements are varied. Some of them are:

- Complexity of the business environment. The increasing complexity of business operations magnifies the difficulty of distilling economic events into summarized reports. Areas such as derivatives, leasing, business combinations, pensions, financing arrangements, revenue recognition, and deferred taxes are complex. As a result, companies extensively use notes to the financial statements to explain these transactions and their future effects.

- Necessity for timely information. Today, more than ever before, users are demanding information that is current and predictive. For example, users want more complete interim data.

- Accounting as a control and monitoring device. Regulators have recently sought public disclosure of such phenomena as management compensation, off-balance-sheet financing arrangements, and related-party transactions. Many of these newer disclosure requirements enlist accountants and auditors as the agents to assist in controlling and monitoring these concerns.

Differential Disclosure

A trend toward differential disclosure is also occurring.1. The IASB has developed IFRS for small- and medium-sized entities (SMEs). SMEs are entities that publish general-purpose financial statements for external users but do not issue shares or other securities in a public market. SMEs are estimated to account for over 95 percent of all companies around the world. Many believe a simplified set of standards makes sense for these companies because they do not have the resources to implement full IFRS.

Simplified IFRS for SMEs is designed to meet their needs and capabilities. Compared with full IFRS (and many national accounting standards), simplified IFRS for SMEs is less complex in a number of ways:

- Topics not relevant for SMEs are omitted. Examples are earnings per share, interim financial reporting, and segment reporting.

- Simplified IFRS for SMEs allows fewer accounting policy choices. For example, there is no option to revalue property, equipment, or intangibles.

- Many principles for recognizing and measuring assets, liabilities, revenue, and expenses are simplified. For example, goodwill is amortized (as a result, there is no annual impairment test) and all borrowing and R&D costs are expensed.

- Significantly fewer disclosures are required (roughly 300 versus 3,000).

- To further reduce standard overload, revisions to the IFRS for SMEs will be limited to once every three years.

Thus, the option of using simplified IFRS helps SMEs meet the needs of their financial statement users while balancing the costs and benefits from a preparer perspective. [2]

NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Explain the use of notes in financial statement preparation.

As you know from your study of this textbook, notes are an integral part of the financial statements of a business enterprise. However, readers of financial statements often overlook them because they are highly technical and often appear in small print. Notes are the means of amplifying or explaining the items presented in the main body of the statements. They can explain in qualitative terms information pertinent to specific financial statement items. In addition, they can provide supplementary data of a quantitative nature to expand the information in the financial statements. Notes also can explain restrictions imposed by financial arrangements or basic contractual agreements. Although notes may be technical and difficult to understand, they provide meaningful information for the user of the financial statements.

Accounting Policies

Accounting policies are the specific principles, bases, conventions, rules, and practices applied by a company in preparing and presenting financial statements. IFRS states that information about the accounting policies adopted by a reporting entity is essential for financial statement users in making economic decisions. It recommends that companies should present as an integral part of the financial statements a statement identifying the accounting policies adopted and followed by the reporting entity. Companies should present the disclosure as the first note or in a separate Summary of Significant Accounting Policies section preceding the notes to the financial statements.

The Summary of Significant Accounting Policies answers such questions as: What method of depreciation is used on plant assets? What valuation method is employed on inventories? What amortization policy is followed in regard to intangible assets? How are marketing costs handled for financial reporting purposes? You can see a good example of note disclosure for Marks and Spencer plc (GBR) (which accompany the financial statements presented in Appendix A) at the company's website, www.marksandspencer.com.

Analysts examine carefully the summary of accounting policies to determine whether a company is taking a conservative or a liberal approach to accounting practices. For example, depreciating plant assets over an unusually long period of time is considered liberal. Using weighted-average inventory valuation in a period of inflation is generally viewed as conservative.

In addition to disclosure of significant accounting policies, companies must:

- Identify the judgments that management made in the process of applying the accounting policies and that have the most significant effect on the amounts recognized in the financial statements, and

- Disclose information about the assumptions they make about the future, and other major sources of estimation uncertainty at the end of the reporting period, that have a significant risk of resulting in a material adjustment to the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities within the next financial year. In respect of those assets and liabilities, the notes shall include details of (a) their nature and (b) their carrying amount as of the end of the reporting period.

These disclosures are many times presented with the accounting policy note or may be provided in a specific policy note. The disclosures should identify the estimates that require management's most difficult, subjective, or complex judgments. [3] An example of this disclosure is presented in Illustration 24-2 for British Airways (GBR).

ILLUSTRATION 24-2

Accounting Estimate and Judgment Disclosure

Collectively, these disclosures help statement readers evaluate the quality of a company's accounting policies in providing information in the financial statements for assessing future cash flows. Companies that fail to adopt high-quality reporting policies may be heavily penalized by the market. For example, when Isoft (GBR) disclosed that it would restate prior-year results due to use of aggressive revenue recognition policies, its share price dropped over 39 percent in one day. Investors viewed Isoft's quality of earnings as low.

Common Notes

We have discussed many of the notes to the financial statements throughout this textbook and will discuss others more fully in this chapter. The more common are as follows.

MAJOR DISCLOSURES

INVENTORY. Companies should report the basis upon which inventory amounts are stated (lower-of-cost-or-net realizable value) and the method used in determining cost (FIFO, average-cost, etc.). Manufacturers should report, either in the statement of financial position or in a separate schedule in the notes, the inventory composition (finished goods, work in process, raw materials). Unusual or significant financing arrangements relating to inventories that may require disclosure include transactions with related parties, product financing arrangements, firm purchase commitments, and pledging of inventories as collateral. Chapter 9 (pages 418–420) illustrates these disclosures.

PROPERTY, PLANT, AND EQUIPMENT. Companies should state the basis of valuation for property, plant, and equipment (e.g., revaluation or historical cost). It is usually historical cost. Companies also should disclose pledges, liens, and other commitments related to these assets. In the presentation of depreciation, companies should disclose the following in the financial statements or in the notes: (1) depreciation expense for the period; (2) balances of major classes of depreciable assets, by nature and function, at the statement date; (3) accumulated depreciation, either by major classes of depreciable assets or in total, at the statement date; and (4) a general description of the method or methods used in computing depreciation with respect to major classes of depreciable assets. Finally, companies should explain any major impairments. Chapter 11 (pages 515–517) illustrates these disclosures.

CREDITOR CLAIMS. Investors normally find it extremely useful to understand the nature and cost of creditor claims. However, the liabilities section in the statement of financial position can provide the major types of liabilities only in the aggregate. Note schedules regarding such obligations provide additional information about how a company is financing its operations, the costs that it will bear in future periods, and the timing of future cash outflows. Financial statements must disclose for each of the five years following the date of the statements the aggregate amount of maturities and sinking fund requirements for all long-term borrowings. Chapter 14 (pages 679–680) illustrates these disclosures.

EQUITYHOLDERS' CLAIMS. Many companies present in the body of the statement of financial position information about equity securities: the number of shares authorized, issued, and outstanding and the par value for each type of security. Or, companies may present such data in a note. Beyond that, a common equity note disclosure relates to contracts and senior securities outstanding that might affect the various claims of the residual equityholders. An example would be the existence of outstanding share options, outstanding convertible debt, redeemable preference shares, and convertible preference shares. In addition, it is necessary to disclose certain types of restrictions currently in force. Generally, these types of restrictions involve the amount of earnings available for dividend distribution. Examples of these types of disclosures are illustrated in Chapter 15 (pages 726–727) and Chapter 16 (page 769).

CONTINGENCIES AND COMMITMENTS. A company may have gain or loss contingencies that are not disclosed in the body of the financial statements. These contingencies include litigation, debt and other guarantees, possible tax assessments, renegotiation of government contracts, and sales of receivables with recourse. In addition, companies should disclose in the notes commitments that relate to dividend restrictions, purchase agreements (through-put and take-or-pay), hedge contracts, and employment contracts. Disclosures of such items are illustrated in Chapter 7 (pages 320–321), Chapter 9 (pages 418–420), and Chapter 13 (pages 623, 625–626).

FAIR VALUES. Companies that have assets or liabilities measured at fair value generally disclose both the cost and the fair value in the notes to the financial statements. Fair value measurements may be used for many financial assets and liabilities; investments; revaluations for property, plant, and equipment; impairments of long-lived assets; and some contingencies. Companies also provide disclosure of information that enables users to determine the extent of usage of fair value and the inputs used to implement fair value measurement. This fair value hierarchy identifies three broad levels related to the measurement of fair values (Levels 1, 2, and 3). The levels indicate the reliability of the measurement of fair value information. Chapter 17 (pages 857–860), discusses in detail fair value disclosures.

DEFERRED TAXES, PENSIONS, AND LEASES. The IASB also requires extensive disclosure in the areas of deferred taxes, pensions, and leases. Chapter 19 (pages 975–978), Chapter 20 (pages 1033–1034), and Chapter 21 (pages 1089–1091) discuss in detail each of these disclosures. Users of financial statements should carefully read notes to the financial statements for information about off-balance-sheet commitments, future financing needs, and the quality of a company's earnings.

CHANGES IN ACCOUNTING POLICIES. The profession defines various types of accounting changes and establishes guides for reporting each type. Companies discuss, either in the summary of significant accounting policies or in the other notes, changes in accounting policies (as well as material changes in estimates and corrections of errors). See Chapter 22 (pages 1135 and 1040).

In earlier chapters, we discussed the disclosures listed above. The following sections of this chapter illustrate four additional disclosures of significance—special transactions or events, subsequent events, segment reporting, and interim reporting.

What do the numbers mean? FOOTNOTE SECRETS

Often, note disclosures are needed to give a complete picture of a company's financial position. A good example is the required disclosure of collateral arrangements in repurchase agreements. Such arrangements gained front-page coverage when it was revealed that Lehman Brothers (USA)—and many other U.S. and European financial institutions—employed specialized repurchase agreements, referred to as Repo 105 (or Repo 108 in Europe), to “window-dress” their statements of financial positions. Here's how it works.

A repurchase agreement amounts to a short-term loan, exchanging collateral for cash upfront and then unwinding the trade as soon as overnight. The Repo 105 that Lehman employed used a variety of holdings as the collateral. Lehman made the exchanges with major global financial institutions, such as Barclays (GBR), UBS (CHE), Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (JPN), and KBC Bank (BEL). What was special about the Repo 105/108 is that the value of the securities that Lehman pledged in the transactions were worth 105 percent of the cash it received. That is, the firm was taking a haircut on the transactions. And when Lehman eventually repaid the cash it received from its counterparties, it did so with interest, making this a rather expensive technique. Under accounting guidance at that time, Lehman could book the transactions as a “sale” rather than a “financing,” as most repos are regarded. That meant that for a few days, Lehman could shuffle off tens of billions of dollars in assets to appear more financially healthy than it really was.

How can you get better informed about note disclosures that may contain important information related to your investments, like Repo 105? Beyond your study in this class, a good online resource for understanding the contents of note disclosures is http://www.footnoted.org/. This site highlights “the things companies bury” in their annual reports. It notes that company reports are more complete of late, but only the largest companies are preparing documents that are readable. As the editor of the site noted, “[some companies] are being dragged kicking and screaming into plain English.”

Sources: Gretchen Morgenson, “Annual Reports: More Pages, but Better?” The New York Times (March 17, 2002); D. Stead, “The Secrets in SEC Filings,” BusinessWeek (August 25, 2008), p. 12; and M. de la Merced and J. Werdigier, “The Origins of Lehman's ‘Repo 105’,” The New York Times (March 12, 2010).

DISCLOSURE ISSUES

Disclosure of Special Transactions or Events

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Discuss the disclosure requirements for related-party transactions, subsequent events, and major business segments.

Related-party transactions, errors, and fraud pose especially sensitive and difficult problems. The accountant/auditor who has responsibility for reporting on these types of transactions must take care to properly balance the rights of the reporting company and the needs of financial statement users.

Related-party transactions arise when a company engages in transactions in which one of the parties has the ability to significantly influence the policies of the other. They may also occur when a non-transacting party has the ability to influence the policies of the two transacting parties.2 Competitive, free-market dealings may not exist in related-party transactions, and so an “arm's-length” basis cannot be assumed. Transactions such as borrowing or lending money at abnormally low or high interest rates, real estate sales at amounts that differ significantly from appraised value, exchanges of non-monetary assets, and transactions involving companies that have no economic substance (“shell corporations”) suggest that related parties may be involved.

In order to make adequate disclosure, companies should report the economic substance, rather than the legal form, of these transactions. IFRS requires the following minimum disclosures of material related-party transactions. [5]

- The nature of the related-party relationship;

- The amount of the transactions and the amount of outstanding balances, including commitments, the nature of consideration, and details of any guarantees given or received;

- Provisions for doubtful debts related to the amount of outstanding balances; and

- The expense recognized during the period in respect of bad or doubtful debts due from related parties.

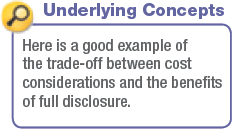

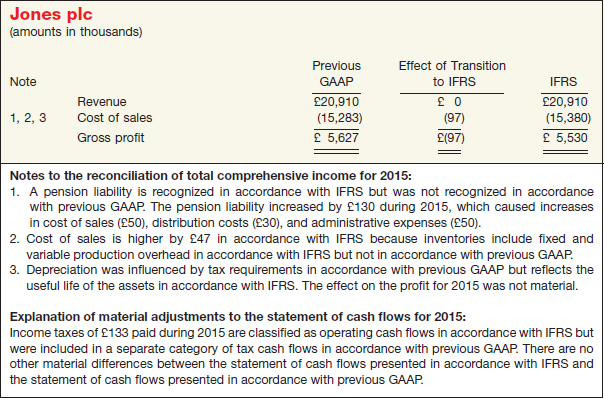

Illustration 24-3, from the annual report of Volvo Group (SWE), shows disclosure of related-party transactions.

ILLUSTRATION 24-3

Disclosure of Related-Party Transactions

Many companies are involved in related-party transactions. However, another type of special event, errors and fraud (sometimes referred to as irregularities), is the exception rather than the rule. Accounting errors are unintentional mistakes, whereas fraud (misappropriation of assets and fraudulent financial reporting) involves intentional distortions of financial statements.3 As indicated earlier, companies should correct the financial statements when they discover errors. The same treatment should be given fraud. The discovery of fraud, however, gives rise to a different set of procedures and responsibilities for the accountant/auditor.

Disclosure plays a very important role in these types of transactions because the events are many times more qualitative than quantitative and involve more subjective than objective evaluation. Users of the financial statements need some indication of the existence and nature of these transactions, through disclosures, modifications in the auditor's report, or reports of changes in auditors.

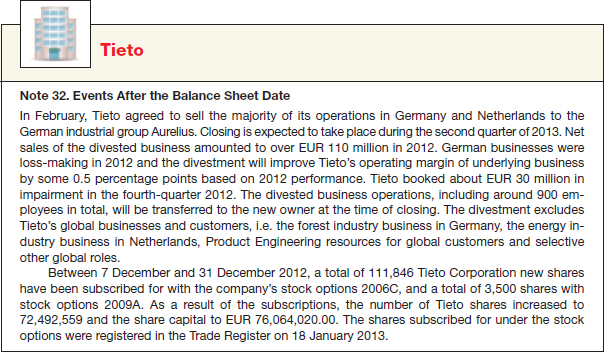

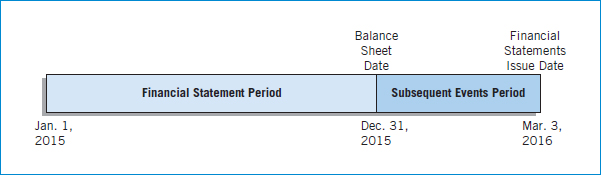

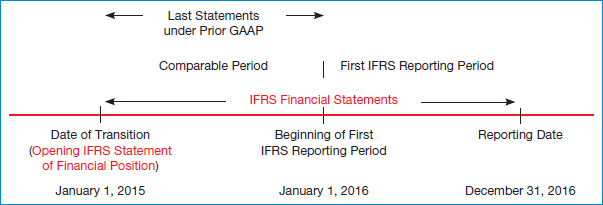

Events after the Reporting Period (Subsequent Events)

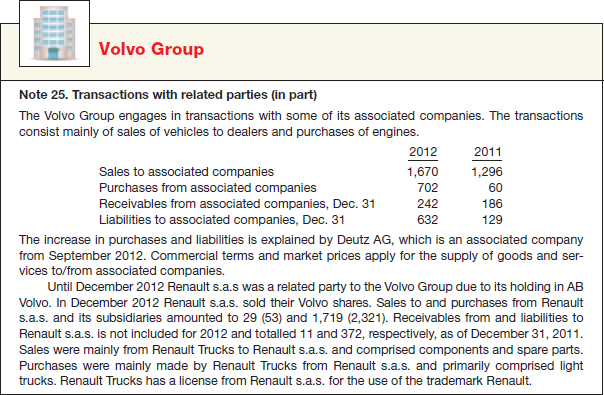

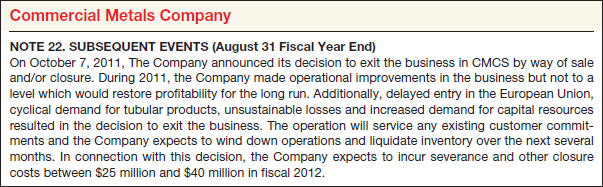

Notes to the financial statements should explain any significant financial events that took place after the formal statement of financial position date, but before the statements are authorized for issuance (hereafter referred to as the authorization date). These events are referred to as events after the reporting date or subsequent events. Illustration 24-4 shows a time diagram of the subsequent events period.

ILLUSTRATION 24-4

Time Periods for Subsequent Events

A period of several weeks or sometimes months may elapse after the end of the fiscal year but before the management or the board of directors authorizes issuance of the financial statements.4 Various activities involved in closing the books for the period and issuing the statements all take time: taking and pricing the inventory, reconciling subsidiary ledgers with controlling accounts, preparing necessary adjusting entries, ensuring that all transactions for the period have been entered, obtaining an audit of the financial statements by independent certified public accountants, and printing the annual report. During the period between the statement of financial position date and its authorization date, important transactions or other events may occur that materially affect the company's financial position or operating situation.

Many who read a statement of financial position believe the financial condition is constant, and they project it into the future. However, readers must be told if the company has experienced a significant change—e.g., sold one of its plants, acquired a subsidiary, suffered unusual losses, settled significant litigation, or experienced any other important event in the post-statement of financial position period. Without an explanation in a note, the reader might be misled and draw inappropriate conclusions.

Two types of events or transactions occurring after the statement of financial position date may have a material effect on the financial statements or may need disclosure so that readers interpret these statements accurately:

- Events that provide additional evidence about conditions that existed at the statement of financial position date, including the estimates inherent in the process of preparing financial statements. These events are referred to as adjusted subsequent events and require adjustments to the financial statements. All information available prior to the authorization date of the financial statements helps investors and creditors evaluate estimates previously made. To ignore these subsequent events is to pass up an opportunity to improve the accuracy of the financial statements. This first type of event encompasses information that an accountant would have recorded in the accounts had the information been known at the statement of financial position date.

For example, if a loss on an account receivable results from a customer's bankruptcy subsequent to the statement of financial position date, the company adjusts the financial statements before their issuance. The bankruptcy stems from the customer's poor financial health existing at the statement of financial position date.

The same criterion applies to settlements of litigation. The company must adjust the financial statements if the events that gave rise to the litigation, such as personal injury or patent infringement, took place prior to the statement of financial position date.

- Events that provide evidence about conditions that did not exist at the statement of financial position date but arise subsequent to that date. These events are referred as non-adjusted subsequent events and do not require adjustment of the financial statements. To illustrate, a loss resulting from a customer's fire or flood after the statement of financial position date does not reflect conditions existing at that date. Thus, adjustment of the financial statements is not necessary. A company should not recognize subsequent events that provide evidence about conditions that did not exist at the date of the statement of financial position but that arose after the statement of financial position date.

The following are examples of non-adjusted subsequent events:

- A major business combination after the reporting period or disposing of a major subsidiary.

- Announcing a plan to discontinue an operation or commencing the implementation of a major restructuring.

- Major purchases of assets, other disposals of assets, or expropriation of major assets by government.

- The destruction of a major production plant or inventories by a fire or natural disaster after the reporting period.

- Major ordinary share transactions and potential ordinary share transactions after the reporting period.

- Abnormally large changes after the reporting period in asset prices, foreign exchange rates, or taxes.

- Entering into significant commitments or contingent liabilities, for example, by issuing significant guarantees after the statement date. [7]5

Some non-adjusted subsequent events may have to be disclosed to keep the financial statements from being misleading. For such events, a company discloses the nature of the event and an estimate of its financial effect.

Illustration 24-5 presents an example of subsequent events disclosure, excerpted from the annual report of Tieto (FIN).

ILLUSTRATION 24-5

Disclosure of Subsequent Events

Many subsequent events or developments do not require adjustment of or disclosure in the financial statements. Typically, these are non-accounting events or conditions that management normally communicates by other means. These events include legislation, product changes, management changes, strikes, unionization, marketing agreements, and loss of important customers.

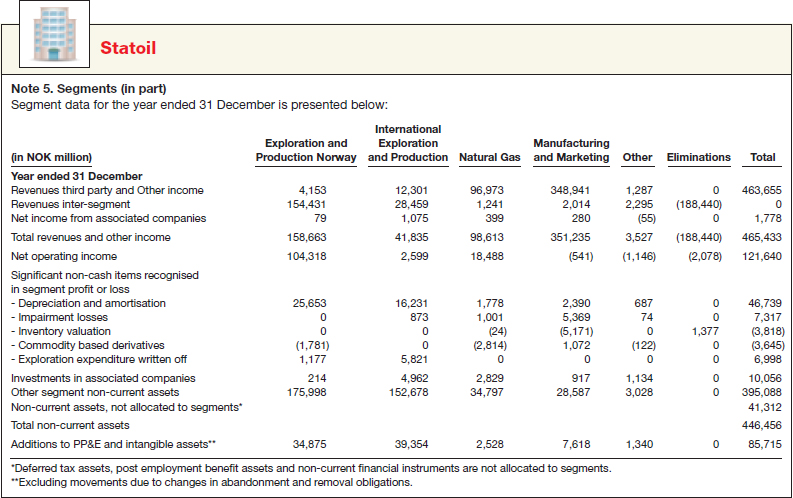

Reporting for Diversified (Conglomerate) Companies

In certain business climates, companies have a tendency to diversify their operations. Take the case of Siemens AG (DEU), whose products include energy technologies, consumer products, and financial services. When businesses are so diversified, investors and investment analysts want more information about the details behind conglomerate financial statements. Particularly, they want income statement, statement of financial position, and cash flow information on the individual segments that compose the total income figure.

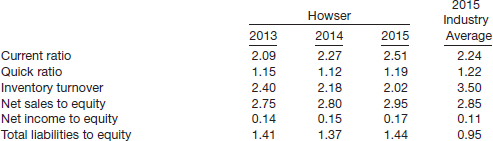

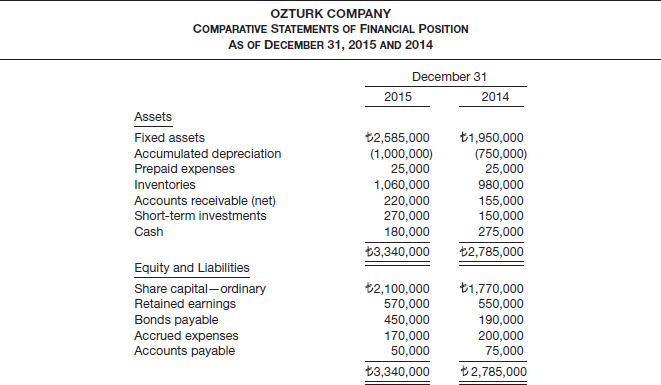

Much information is hidden in the aggregated totals. With only the consolidated figures, the analyst cannot tell the extent to which the differing product lines contribute to the company's profitability, risk, and growth potential. For example, in Illustration 24-6, the office equipment segment looks like a risky venture. Segmented reporting would provide useful information about the two business segments and would be useful for making an informed investment decision regarding the whole company.

ILLUSTRATION 24-6

Segmented Income Statement

A classic situation that demonstrates the need for segmented data involved Caterpillar, Inc. (USA). Market regulators cited Caterpillar because it failed to tell investors that nearly a quarter of its income in one year came from a Brazilian unit and was non-recurring in nature. The company knew that different economic policies in the next year would probably greatly affect earnings of the Brazilian unit. But Caterpillar presented its financial results on a consolidated basis, not disclosing the Brazilian operations. Caterpillar's failure to include information about Brazil left investors with an incomplete picture of the company's financial results and denied investors the opportunity to see the company “through the eyes of management.”

Companies have always been somewhat hesitant to disclose segmented data for various reasons:

- Without a thorough knowledge of the business and an understanding of such important factors as the competitive environment and capital investment requirements, the investor may find the segmented information meaningless or may even draw improper conclusions about the reported earnings of the segments.

- Additional disclosure may be helpful to competitors, labor unions, suppliers, and certain government regulatory agencies, and thus harm the reporting company.

- Additional disclosure may discourage management from taking intelligent business risks because segments reporting losses or unsatisfactory earnings may cause shareholder dissatisfaction with management.

- The wide variation among companies in the choice of segments, cost allocation, and other accounting problems limits the usefulness of segmented information.

- The investor is investing in the company as a whole and not in the particular segments, and it should not matter how any single segment is performing if the overall performance is satisfactory.

- Certain technical problems, such as classification of segments and allocation of segment revenues and costs (especially “common costs”), are formidable.

On the other hand, the advocates of segmented disclosures offer these reasons in support of the practice:

- Investors need segmented information to make an intelligent investment decision regarding a diversified company.

- (a) Sales and earnings of individual segments enable investors to evaluate the differences between segments in growth rate, risk, and profitability, and to forecast consolidated profits.

- (b) Segmented reports help investors evaluate the company's investment worth by disclosing the nature of a company's businesses and the relative size of the components.

- The absence of segmented reporting by a diversified company may put its unsegmented, single product-line competitors at a competitive disadvantage because the conglomerate may obscure information that its competitors must disclose.

The advocates of segmented disclosures appear to have a much stronger case. Many users indicate that segmented data are the most useful financial information provided, aside from the basic financial statements. As a result, the IASB has issued extensive reporting guidelines in this area.

Objective of Reporting Segmented Information

The objective of reporting segmented financial data is to provide information about the different types of business activities in which an enterprise engages and the different economic environments in which it operates. Meeting this objective will help users of financial statements do the following.

- (a) Better understand the enterprise's performance.

- (b) Better assess its prospects for future net cash flows.

- (c) Make more informed judgments about the enterprise as a whole.

Basic Principles

Financial statements can be disaggregated in several ways. For example, they can be disaggregated by products or services, by geography, by legal entity, or by type of customer. However, it is not feasible to provide all of that information in every set of financial statements. IFRS requires that general-purpose financial statements include selected information on a single basis of segmentation. Thus, a company can meet the segmented reporting objective by providing financial statements segmented based on how the company's operations are managed. The method chosen is referred to as the management approach. [8] The management approach reflects how management segments the company for making operating decisions. The segments are evident from the components of the company's organization structure. These components are called operating segments.

Identifying Operating Segments

An operating segment is a component of an enterprise:

- (a) That engages in business activities from which it earns revenues and incurs expenses.

- (b) Whose operating results are regularly reviewed by the company's chief operating decision-maker to assess segment performance and allocate resources to the segment.

- (c) For which discrete financial information is available that is generated by or based on the internal financial reporting system.

Companies may aggregate information about two or more operating segments only if the segments have the same basic characteristics in each of the following areas.

- (a) The nature of the products and services provided.

- (b) The nature of the production process.

- (c) The type or class of customer.

- (d) The methods of product or service distribution.

- (e) If applicable, the nature of the regulatory environment.

After the company decides on the possible segments for disclosure, it makes a quantitative materiality test. This test determines whether the segment is significant enough to warrant actual disclosure. An operating segment is deemed significant and therefore a reportable segment if it satisfies one or more of the following quantitative thresholds.

- Its revenue (including both sales to external customers and intersegment sales or transfers) is 10 percent or more of the combined revenue of all the company's operating segments.

- The absolute amount of its profit or loss is 10 percent or more of the greater, in absolute amount, of (a) the combined operating profit of all operating segments that did not incur a loss, or (b) the combined loss of all operating segments that did report a loss.

- Its identifiable assets are 10 percent or more of the combined assets of all operating segments.

In applying these tests, the company must consider two additional factors. First, segment data must explain a significant portion of the company's business. Specifically, the segmented results must equal or exceed 75 percent of the combined sales to unaffiliated customers for the entire company. This test prevents a company from providing limited information on only a few segments and lumping all the rest into one category.

Second, the profession recognizes that reporting too many segments may overwhelm users with detailed information. The IASB decided that 10 is a reasonable upper limit for the number of segments that a company must disclose. [9]

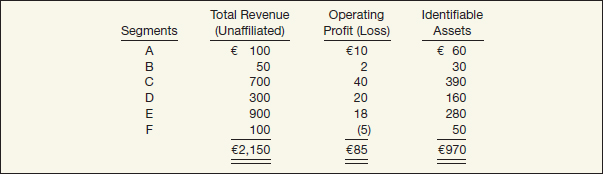

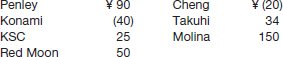

To illustrate these requirements, assume a company has identified six possible reporting segments, as shown in Illustration 24-7 (euros in thousands).

ILLUSTRATION 24-7

Data for Different Possible Reporting Segments

The company would apply the respective tests as follows.

Revenue test: 10% × €2,150 = €215; C, D, and E meet this test.

Operating profit (loss) test: 10% × €90 = €9 (note that the €5 loss is ignored, because the test is based on non-loss segments); A, C, D, and E meet this test.

Identifiable assets tests: 10% × €970 = €97; C, D, and E meet this test.

The reporting segments are therefore A, C, D, and E, assuming that these four segments have enough sales to meet the 75 percent of combined sales test. The 75 percent test is computed as follows.

75% of combined sales test: 75% × €2,150 = €1,612.50. The sales of A, C, D, and E total €2,000 (€100 + €700 + €300 + €900); therefore, the 75 percent test is met.

Measurement Principles

The accounting principles that companies use for segment disclosure need not be the same as the principles they use to prepare the consolidated statements. This flexibility may at first appear inconsistent. But, preparing segment information in accordance with IFRS would be difficult because some IFRS are not expected to apply at a segment level. Examples are accounting for the cost of company-wide employee benefit plans and accounting for income taxes in a company that files a consolidated tax return with segments in different tax jurisdictions.

The IASB does not require allocations of joint, common, or company-wide costs solely for external reporting purposes. Common costs are those incurred for the benefit of more than one segment and whose interrelated nature prevents a completely objective division of costs among segments. For example, the company president's salary is difficult to allocate to various segments. Allocations of common costs are inherently arbitrary and may not be meaningful. There is a presumption that if companies allocate common costs to segments, these allocations are either directly attributable or reasonably allocable to the segments.

Segmented Information Reported

The IASB requires that an enterprise report the following.

- General information about its operating segments. This includes factors that management considers most significant in determining the company's operating segments and the types of products and services from which each operating segment derives its revenues.

- Segment profit and loss and related information. Specifically, companies must report the following information about each operating segment if the amounts are included in determining segment profit or loss.

- (a) Revenues from transactions with external customers.

- (b) Revenues from transactions with other operating segments of the same enterprise.

- (c) Interest revenue.

- (d) Interest expense.

- (e) Depreciation and amortization expense.

- (f) Unusual items.

- (g) Equity in the net income of investees accounted for by the equity method.

- (h) Income tax expense or benefit.

- (i) Significant non-cash items other than depreciation, depletion, and amortization expense.

- Segment assets and liabilities. A company must report each operating segment's total assets and liabilities.

- Reconciliations. A company must provide a reconciliation of the total of the segments' revenues to total revenues, a reconciliation of the total of the operating segments' profits and losses to its income before income taxes, and a reconciliation of the total of the operating segments' assets and liabilities to total assets and liabilities.

- Information about products and services and geographic areas. For each operating segment not based on geography, the company must report (unless it is impracticable): (1) revenues from external customers, (2) long-lived assets, and (3) expenditures during the period for long-lived assets. This information, if material, must be reported (a) in the enterprise's country of domicile and (b) in each other country.

- Major customers. If 10 percent or more of company revenue is derived from a single customer, the company must disclose the total amount of revenue from each such customer by segment.

Illustration of Disaggregated Information

Illustration 24-8 shows the segment disclosure for Statoil (NOR).

ILLUSTRATION 24-8

Segment Disclosure

Interim Reports

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Describe the accounting problems associated with interim reporting.

Another source of information for the investor is interim reports. As noted earlier, interim reports cover periods of less than one year. The securities exchanges, market regulators, and the accounting profession have an active interest in the presentation of interim information.

Because of the short-term nature of the information in these reports, there is considerable controversy as to the general approach companies should employ. One group, which favors the discrete approach, believes that companies should treat each interim period as a separate accounting period. Using that treatment, companies would follow the principles for deferrals and accruals used for annual reports. In this view, companies should report accounting transactions as they occur, and expense recognition should not change with the period of time covered.

Another group, which favors the integral approach, believes that the interim report is an integral part of the annual report and that deferrals and accruals should take into consideration what will happen for the entire year. In this approach, companies should assign estimated expenses to parts of a year on the basis of sales volume or some other activity base. In general, IFRS requires companies to follow the discrete approach. [10]

Interim Reporting Requirements

Generally, companies should use the same accounting policies for interim reports and for annual reports. They should recognize revenues in interim periods on the same basis as they are for annual periods. For example, if Cedars Corp. uses the percentage-of-completion method as the basis for recognizing revenue on an annual basis, then it should use the percentage-of-completion method for interim reports as well. Also, Cedars should treat costs directly associated with revenues (product costs, such as materials, labor and related fringe benefits, and manufacturing overhead) in the same manner for interim reports as for annual reports.

Companies should use the same inventory pricing methods (FIFO, average-cost, etc.) for interim reports and for annual reports. However, companies may use the gross profit method for interim inventory pricing. But, they must disclose the method and adjustments to reconcile with annual inventory.

Discrete Approach. Following the discrete approach, companies record in interim reports revenues and expenses according to the revenue and expense recognition principles. This includes costs and expenses other than product costs (often referred to as period costs). No accruals or deferrals in anticipation of future events during the year should be reported. For example, the cost of a planned major periodic maintenance or overhaul for a company like Airbus (FRA) or other seasonal expenditure that is expected to occur late in the year is not anticipated for interim reporting purposes. The mere intention or necessity to incur expenditure related to the future is not sufficient to give rise to an obligation.

Or, a company like Carrefour (FRA) may budget certain costs expected to be incurred irregularly during the financial year, such as advertising and employee training costs. Those costs generally are discretionary even though they are planned and tend to recur from year to year. However, recognizing an obligation at the end of an interim financial reporting period for such costs that have not yet been incurred generally is not consistent with the definition of a liability.

While year-to-date measurements may involve changes in estimates of amounts reported in prior interim periods of the current financial year, the principles for recognizing assets, liabilities, income, and expenses for interim periods are the same as in annual financial statements. For example, Wm Morrison Supermarkets plc (GBR) records losses from inventory write-downs, restructurings, or impairments in an interim period similar to how it would treat these items in the annual financial statements (when incurred). However, if an estimate from a prior interim period changes in a subsequent interim period of that year, the original estimate is adjusted in the subsequent interim period.

Interim Disclosures. IFRS does not require a complete set of financial statements at the interim reporting date. Rather, companies may comply with the requirements by providing condensed financial statements and selected explanatory notes. Because users of interim financial reports also have access to the most recent annual financial report, companies only need provide explanation of significant events and transactions since the end of the last annual reporting period. Companies should report the following interim data at a minimum.

- 1. Statement that the same accounting policies and methods of computation are followed in the interim financial statements as compared with the most recent annual financial statements or, if those policies or methods have been changed, a description of the nature and effect of the change.

- 2. Explanatory comments about the seasonality or cyclicality of interim operations.

- 3. The nature and amount of items affecting assets, liabilities, equity, net income, or cash flows that are unusual because of their nature, size, or incidence.

- 4. The nature and amount of changes in accounting policies and estimates of amounts previously reported.

- 5. Issuances, repurchases, and repayments of debt and equity securities.

- 6. Dividends paid (aggregate or per share) separately for ordinary shares and other shares.

- 7. Segment information, as required by IFRS 8, “Operating Segments.”

- 8. Changes in contingent liabilities or contingent assets since the end of the last annual reporting period.

- 9. Effect of changes in the composition of the company during the interim period, such as business combinations, obtaining or losing control of subsidiaries and long-term investments, restructurings, and discontinued operations.

- 10. Other material events subsequent to the end of the interim period that have not been reflected in the financial statements for the interim period.

If a complete set of financial statements is provided in the interim report, companies comply with the provisions of IAS 1, “Presentation of Financial Statements.”

Unique Problems of Interim Reporting

IFRS reflects a preference for the discrete approach. However, within this broad guideline, a number of unique reporting problems develop related to the following items.

Income Taxes. Not every dollar of corporate taxable income may be taxed at the same rate if the tax rate is progressive. This aspect of business income taxes poses a problem in preparing interim financial statements. Should the company use the annualized approach, which is to annualize income to date and accrue the proportionate income tax for the period to date? Or should it follow the marginal principle approach, which is to apply the lower rate of tax to the first amount of income earned? At one time, companies generally followed the latter approach and accrued the tax applicable to each additional dollar of income.

IFRS requires use of the annualized approach. Income tax expense is recognized in each interim period based on the best estimate of the weighted-average annual income tax rate expected for the full financial year. This approach is consistent with applying the same principles in interim reports as applied to annual report; that is, income taxes are assessed on an annual basis. However, amounts accrued for income tax expense in one interim period may have to be adjusted in a subsequent interim period of that financial year if the estimate of the annual income tax rate changes. [11]6

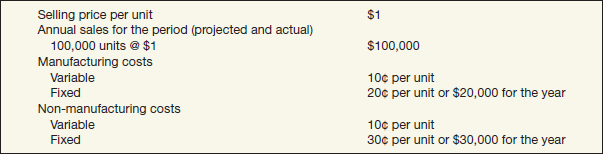

Seasonality. Seasonality occurs when most of a company's sales occur in one short period of the year, while certain costs are fairly evenly spread throughout the year. For example, the natural gas industry has its heavy sales in the winter months. In contrast, the beverage industry has its heavy sales in the summer months.

The problem of seasonality is related to the expense recognition principle in accounting. Generally, expenses are associated with the revenues they create. In a seasonal business, wide fluctuations in profits occur because off-season sales do not absorb the company's fixed costs (for example, manufacturing, selling, and administrative costs that tend to remain fairly constant regardless of sales or production).

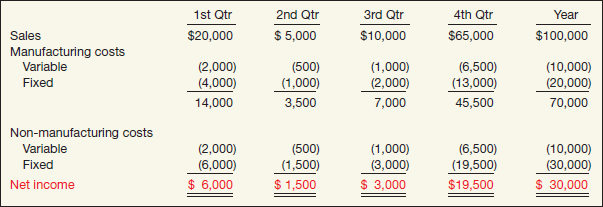

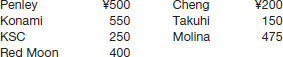

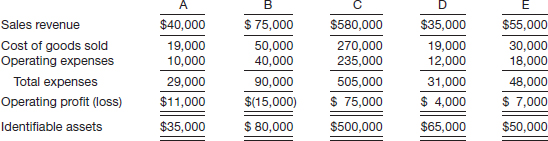

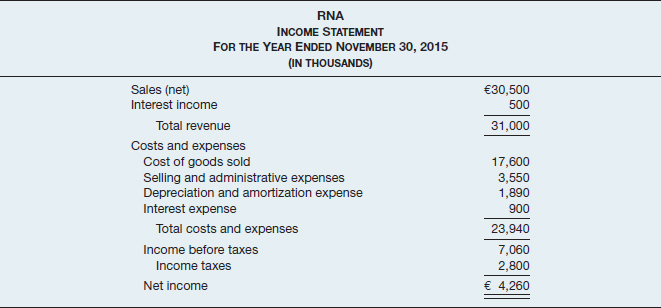

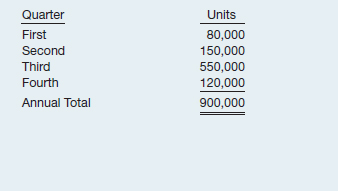

To illustrate why seasonality is a problem, assume the following information.

ILLUSTRATION 24-9

Data for Seasonality Example

Sales for four quarters and the year (projected and actual) were as follows.

ILLUSTRATION 24-10

Sales Data for Seasonality Example

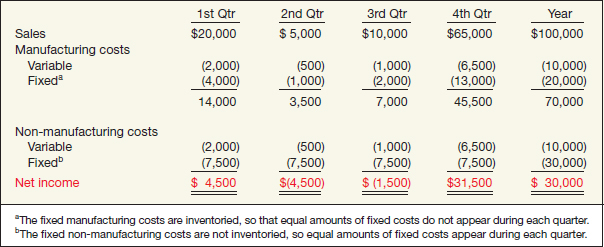

Under the present accounting framework, the income statements for the quarters might be as shown in Illustration 24-11.

ILLUSTRATION 24-11

Interim Net Income for Seasonal Business—Discrete Approach

An investor who uses the first quarter's results might be misled. If the first quarter's earnings are $4,500, should this figure be multiplied by four to predict annual earnings of $18,000? Or, if first-quarter sales of $20,000 are 20 percent of the predicted sales for the year, would the net income for the year be $22,500 ($4,500 × 5)? Both figures are obviously wrong. And, after the second quarter's results occur, the investor may become even more confused.

The problem with the conventional approach is that the fixed non-manufacturing costs are not charged in proportion to sales. Some enterprises have adopted a way of avoiding this problem by making all fixed non-manufacturing costs follow the sales pattern, as shown in Illustration 24-12.

ILLUSTRATION 24-12

Interim Net Income for Seasonal Business—Integral Approach

This approach solves some of the problems of interim reporting: Sales in the first quarter are 20 percent of total sales for the year, and net income in the first quarter is 20 percent of total income. In this case, as in the previous example, the investor cannot rely on multiplying any given quarter by four but can use comparative data or rely on some estimate of sales in relation to income for a given period.

The greater the degree of seasonality experienced by a company, the greater the possibility of distortion. Because there are no definitive guidelines for handling such items as the fixed non-manufacturing costs, variability in income can be substantial. To alleviate this problem, IFRS requires companies subject to material seasonal variations to disclose the seasonal nature of their business and consider supplementing their interim reports with information for 12-month periods ended at the interim date for the current and preceding years.

The two illustrations highlight the difference between the discrete and integral approaches. Illustration 24-11 (page 1269) represents the discrete approach, in which the fixed non-manufacturing expenses are expensed as incurred. Illustration 24-12 (page 1269) shows the integral approach, in which expenses are charged to expense on the basis of some measure of activity.

Continuing Controversy. While IFRS has developed some rules for interim reporting, additional issues remain. For example, there is continuing debate on the independent auditor's involvement in interim reports. Many auditors are reluctant to express an opinion on interim financial information, arguing that the data are too tentative and subjective. On the other hand, more people are advocating some examination of interim reports. Generally, auditors perform a review of interim financial information. Such a review, which is much more limited in its procedures than the annual audit, provides some assurance that the interim information appears to be in accord with IFRS.7

Analysts and investors want financial information as soon as possible, before it is old news. We may not be far from a continuous database system in which corporate financial records can be accessed online. Investors might be able to access a company's financial records whenever they wish and put the information in the format they need. Thus, they could learn about sales slippage, cost increases, or earnings changes as they happen, rather than waiting until after the quarter has ended.

A steady stream of information from the company to the investor could be very positive because it might alleviate management's continual concern with short-run interim numbers. Today, many contend that management is too oriented to the short-term. The truth of this statement is echoed by the words of the president of a large company who decided to retire early: “I wanted to look forward to a year made up of four seasons rather than four quarters.”

AUDITOR'S AND MANAGEMENT'S REPORTS

Auditor's Report

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Identify the major disclosures in the auditor's report.

Another important source of information that is often overlooked is the auditor's report. An auditor is an accounting professional who conducts an independent examination of a company's accounting data.

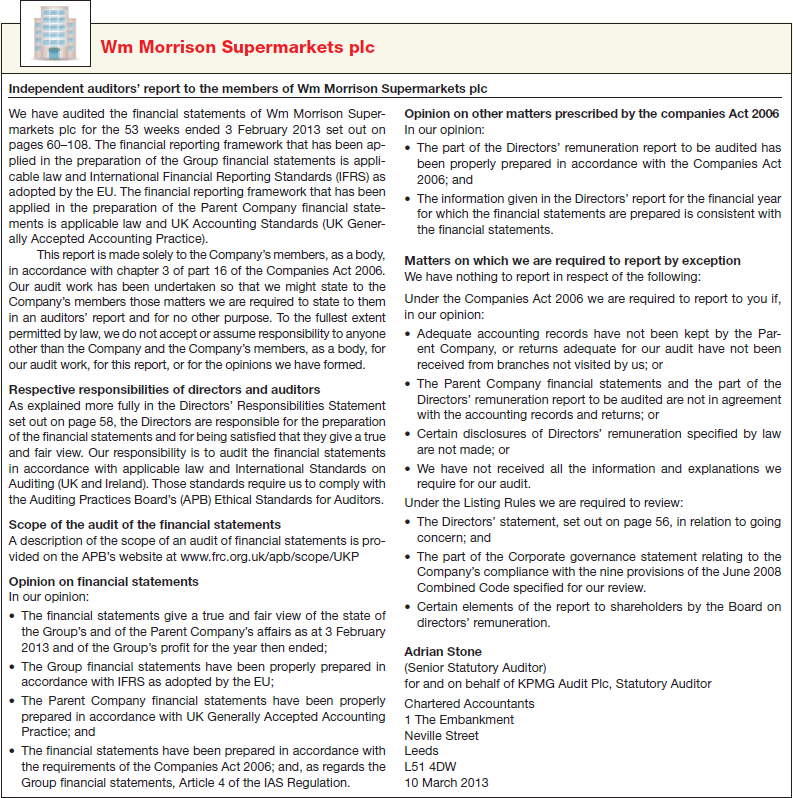

If satisfied that the financial statements present the financial position, results of operations, and cash flows fairly in accordance with IFRS, the auditor expresses an unmodified opinion. An example is shown in Illustration 24-13.8

ILLUSTRATION 24-13

Auditor's Report

In preparing the report, the auditor follows these reporting standards.

- 1. The report states whether the financial statements are in accordance with the financial reporting framework (IFRS) and describes the responsibilities of the directors and auditors with respect to the financial statements.

- 2. The report identifies those circumstances in which the company has not consistently observed such policies in the current period in relation to the preceding period.

- 3. Users are to regard the informative disclosures in the financial statements as reasonably adequate unless the report states otherwise.

- 4. The report contains either an expression of opinion regarding the financial statements taken as a whole or an assertion to the effect that an opinion cannot be expressed. When the auditor cannot express an overall opinion, the report should state the reasons. In all cases where an auditor's name is associated with financial statements, the report should contain a clear-cut indication of the character of the auditor's examination, if any, and the degree of responsibility being taken.

In most cases, the auditor issues a standard unmodified or clean opinion, as shown in Illustration 24-13. That is, the auditor expresses the opinion that the financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position, results of operations, and cash flows of the entity in conformity with accepted accounting principles.

Certain circumstances, although they do not affect the auditor's unmodified opinion, may require the auditor to add an explanatory paragraph to the audit report. Some of the more important circumstances are as follows.

- 1. Going concern. The auditor must evaluate whether there is substantial doubt about the entity's ability to continue as a going concern for a reasonable period of time, taking into consideration all available information about the future. (Generally, the future is at least, but not limited to, 12 months from the end of the reporting period.) If substantial doubt exists about the company continuing as a going concern, the auditor adds to the report an explanatory note describing the potential problem.

- 2. Lack of consistency. If a company has changed accounting policies or the method of their application in a way that has a material effect on the comparability of its financial statements, the auditor should refer to the change in an explanatory paragraph of the report. Such an explanatory paragraph should identify the nature of the change and refer readers to the note in the financial statements that discusses the change in detail. The auditor's concurrence with a change is implicit unless the auditor takes exception to the change in expressing an opinion as to fair presentation in conformity with accepted accounting principles (IFRS).

- 3. Emphasis of a matter. The auditor may wish to emphasize a matter regarding the financial statements but nevertheless intends to express an unqualified opinion. For example, the auditor may wish to emphasize that the entity is a component of a larger business enterprise or that it has had significant transactions with related parties. The auditor presents such explanatory information in a separate paragraph of the report.

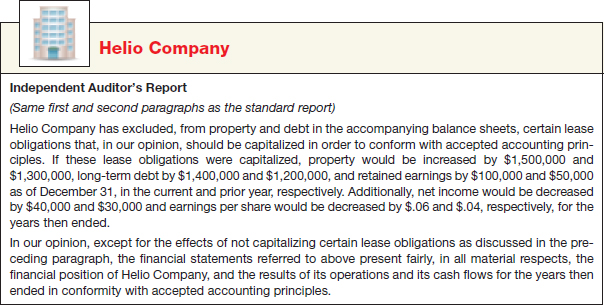

In some situations, however, the auditor expresses a modified opinion. A modified opinion can be either (1) a qualified opinion, (2) an adverse opinion, or (3) a disclaimed opinion.

A qualified opinion contains an exception to the standard opinion. Ordinarily, the exception is not of sufficient magnitude to invalidate the statements as a whole; if it were, an adverse opinion would be rendered. The usual circumstances in which the auditor may deviate from the standard unqualified report on financial statements are as follows.

- 1. The scope of the examination is limited or affected by conditions or restrictions.

- 2. The statements do not fairly present financial position or results of operations because of:

- (a) Lack of conformity with accepted accounting principles and standards.

- (b) Inadequate disclosure.

If confronted with one of the situations noted above, the auditor must offer a qualified opinion. A qualified opinion states that, except for the effects of the matter to which the qualification relates, the financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the financial position, results of operations, and cash flows in conformity with accepted accounting principles.

Illustration 24-14 shows an example of an auditor's report with a modified opinion—in this case, a qualified opinion of Helio Company (USA). The auditor modified the opinion because the company used an accounting policy at variance with accepted accounting principles.

ILLUSTRATION 24-14

Auditor's Report with Qualified Opinion

An adverse opinion is required in any report in which the exceptions to fair presentation are so material that in the independent auditor's judgment, a qualified opinion is not justified. In such a case, the financial statements taken as a whole are not presented in accordance with IFRS. Adverse opinions are rare because most companies change their accounting to conform with IFRS. Market regulators will not permit a company listed on an exchange to have an adverse opinion.

A disclaimer of an opinion is appropriate when the auditor has gathered so little information on the financial statements that no opinion can be expressed.

The audit report should provide useful information to the investor. One investment banker noted, “Probably the first item to check is the auditor's opinion to see whether or not it is a clean one—'in conformity with accepted accounting principles'—or is qualified in regard to differences between the auditor and company management in the accounting treatment of some major item, or in the outcome of some major litigation.”

What do the numbers mean? HEART OF THE MATTER

Financial disclosure is one of a number of institutional features that contribute to healthy security markets. In fact, a recent study of disclosure and other mechanisms (such as civil lawsuits and criminal sanctions) found that good disclosure is the most important contributor to a vibrant market. The study, which compared disclosure and other legal and regulatory elements across 49 countries, found that countries with the best disclosure laws have the biggest securities markets.

Countries with more successful market environments also tend to have regulations that make it relatively easy for private investors to sue corporations that provide bad information. That is, while criminal sanctions can be effective in some circumstances, disclosure and other legal and regulatory elements encouraging good disclosure are the most important determinants of highly liquid and deep securities markets.

These findings hold for nations in all stages of economic development, with particular importance for nations that are in the early stages of securities regulation. In addition, countries with fewer market protections likely will benefit the most from adoption of international standards for market regulation and disclosure. The lesson: Disclosure is good for your market.

Sources: Rebecca Christie, “Study: Disclosure at Heart of Effective Securities Laws,” Wall Street Journal Online (August 11, 2003); and L. Hail, C. Leuz, and P. Wysocki, “Global Accounting Convergence and the Potential Adoption of IFRS by the U.S. (Part I): Conceptual Underpinnings and Economic Analysis,” Accounting Horizons (September 2010).

Management's Reports

Management Commentary

LEARNING OBJECTIVE ![]()

Understand management's responsibilities for financials.

Management commentary helps in the interpretation of the financial position, financial performance, and cash flows of a company. For example, a company like Delhaize Group (BEL) may present, outside the financial statements, a financial review by management that describes and explains the main features of the company's financial performance and financial position, and the principal uncertainties it faces. Such a report may include a review of:

- The main factors and influences determining financial performance, including changes in the environment in which the entity operates, the entity's response to those changes and their effect, and the company's policy for investment to maintain and enhance financial performance, including its dividend policy;

- The company's sources of funding and its targeted ratio of liabilities to equity; and

- The company's resources not recognized in the statement of financial position in accordance with IFRS.

Such commentary also provides an opportunity to understand management's objectives and its strategies for achieving those objectives. Users of financial reports, in their capacity as capital providers, routinely use the type of information provided in management commentary as a tool for evaluating an entity's prospects and its general risks, as well as the success of management's strategies for achieving its stated objectives.

For many companies, management commentary is already an important element of their communication with the capital markets, supplementing as well as complementing the financial statements. Management commentary encompasses reporting that is described in various jurisdictions as management's discussion and analysis (MD&A), operating and financial review (OFR), or management's report.

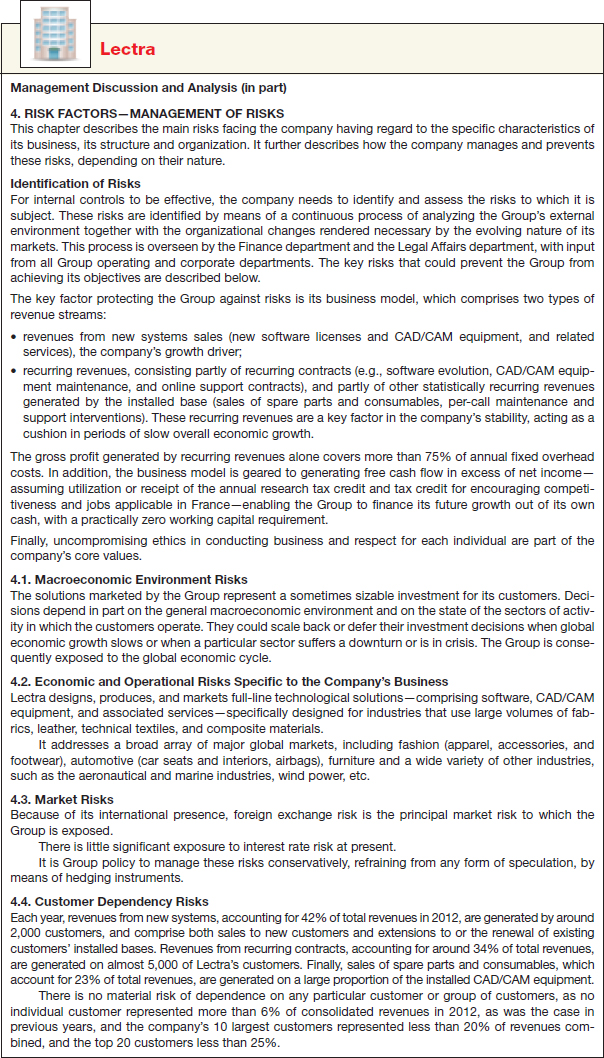

Illustration 24-15 presents an excerpt from the MD&A section of Lectra's (FRA) annual report.

ILLUSTRATION 24-15

Management's Discussion and Analysis

Some companies use the management commentary section of the annual report to disclose company efforts in the area of sustainability. An excerpt from the annual report of Marks and Spencer plc (GBR) is presented in Illustration 24-16.

ILLUSTRATION 24-16

Sustainability Reporting

Additional reporting on sustainability is important because it indicates the company's social responsibility and can provide insights about potential obligations that are reported in the financial statements.

While there are no formal IFRS requirements for management commentary, the IASB has initiated a project that offers a non-binding framework and limited guidance on its application, which could be adapted to the legal and economic circumstances of individual jurisdictions. While the proposal is focused on publicly traded entities, to the extent that the framework is deemed applicable, it may be a useful tool for non-exchange traded entities, for example, privately held and state-owned enterprises.9

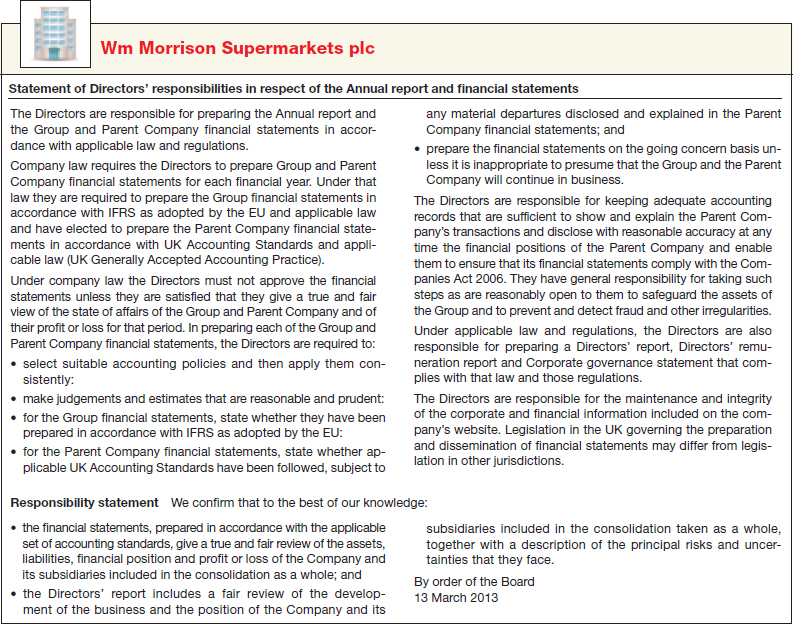

Management's Responsibilities for Financial Statements

Management is responsible for preparing the financial statements and establishing and maintaining an effective system of internal controls. The auditor provides an independent assessment of whether the financial statements are prepared in accordance with IFRS (see the audit opinion in Illustration 24-13 on page 1271). An example of the type of disclosure that public companies are now making is shown in Illustration 24-17.

ILLUSTRATION 24-17

Report on Management's Responsibilities

CURRENT REPORTING ISSUES

Reporting on Financial Forecasts and Projections

In recent years, the investing public's demand for more and better information has focused on disclosure of corporate expectations for the future.10 These disclosures take one of two forms:11.

![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVE

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Identify issues related to financial forecasts and projections.

- Financial forecasts. A financial forecast is a set of prospective financial statements that present, to the best of the responsible party's knowledge and belief, a company's expected financial position, results of operations, and cash flows. The responsible party bases a financial forecast on conditions it expects to exist and the course of action it expects to take.

- Financial projections. Financial projections are prospective financial statements that present, to the best of the responsible party's knowledge and belief, given one or more hypothetical assumptions, an entity's expected financial position, results of operations, and cash flows. The responsible party bases a financial projection on conditions it expects would exist and the course of action it expects would be taken, given one or more hypothetical assumptions.

The difference between a financial forecast and a financial projection is clear-cut: A forecast provides information on what is expected to happen, whereas a projection provides information on what might take place but is not necessarily expected to happen.

Whether companies should be required to provide financial forecasts is the subject of intensive discussion with journalists, corporate executives, market regulators, financial analysts, accountants, and others. Predictably, there are strong arguments on either side. Listed below are some of the arguments.

Arguments for requiring published forecasts:

- 1. Investment decisions are based on future expectations. Therefore, information about the future facilitates better decisions.

- 2. Companies already circulate forecasts informally. This situation should be regulated to ensure that the forecasts are available to all investors.

- 3. Circumstances now change so rapidly that historical information is no longer adequate for prediction.

Arguments against requiring published forecasts:

- 1. No one can foretell the future. Therefore, forecasts will inevitably be wrong. Worse, they may mislead if they convey an impression of precision about the future.

- 2. Companies may strive only to meet their published forecasts, thereby failing to produce results that are in the shareholders' best interest.

- 3. If forecasts prove inaccurate, there will be recriminations and probably legal actions.12

- 4. Disclosure of forecasts will be detrimental to organizations because forecasts will inform competitors (foreign and domestic), as well as investors.

Auditing standards establish guidelines for the preparation and presentation of financial forecasts and projections.13 They require accountants to provide (1) a summary of significant assumptions used in the forecast or projection and (2) guidelines for minimum presentation.

To encourage management to disclose prospective financial information, some market regulators have established a safe harbor rule. It provides protection to a company that presents an erroneous forecast, as long as the company prepared the forecast on a reasonable basis and disclosed it in good faith.14 However, many companies note that the safe harbor rule does not work in practice, since it does not cover oral statements, nor has it kept them from investor lawsuits.

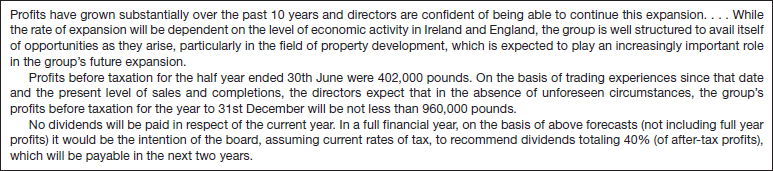

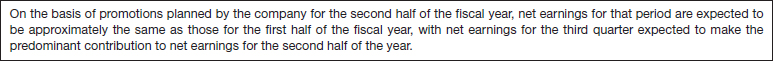

What do the numbers mean? GLOBAL FORECASTS

Great Britain permits financial forecasts, and the results have been fairly successful. Some significant differences do exist between the English and other business and legal environments. The British system, for example, does not permit litigation on forecasted information, and the solicitor (lawyer) is not permitted to work on a contingent-fee basis. A typical British forecast adapted from a construction company's report to support a public offering of shares is as follows.

A general narrative-type forecast might appear as follows.

As indicated, the general version is much less specific in its forecasted information.

But such differences probably could be overcome if influential interests cooperated to produce an atmosphere conducive to quality forecasting. What do you think? As an investor, would you prefer the more specific forecast?

Source: See “A Case for Forecasting—The British Have Tried It and Find That It Works,” World (New York: Peat, Marwick, Mitchell & Co., Autumn 1978), pp. 10–13. In a recent survey, U.K. companies remain stubbornly backward-looking. Just 5 percent of FTSE 100 companies address the future of the business in their discussion and analysis. See PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Guide to Forward-looking Information: Don't Fear the Future” (2006).

Questions of Liability

What happens if a company does not meet its forecasts? Can the company and the auditor be sued? If a company, for example, projects an earnings increase of 15 percent and achieves only 5 percent, should shareholders be permitted to have some judicial recourse against the company?

One court case involving Monsanto Chemical Corporation (USA) set a precedent. In this case, Monsanto predicted that sales would increase 8 to 9 percent and that earnings would rise 4 to 5 percent. In the last part of the year, the demand for Monsanto's products dropped as a result of a business turndown. Instead of increasing, the company's earnings declined. Investors sued the company because the projected earnings figure was erroneous, but a judge dismissed the suit because the forecasts were the best estimates of qualified people whose intents were honest.

As indicated earlier, safe harbor rules are intended to protect companies that provide good-faith projections. However, much concern exists as to how market regulators and the courts will interpret such terms as “good faith” and “reasonable assumptions” when erroneous forecasts mislead users of this information.

Internet Financial Reporting

Most companies now use the power and reach of the Internet to provide more useful information to financial statement readers. All large companies have Internet sites, and a large proportion of companies' websites contain links to their financial statements and other disclosures. The popularity of such reporting is not surprising as companies can reduce the costs of printing and disseminating paper reports with the use of Internet reporting.

Does Internet financial reporting improve the usefulness of a company's financial reports? Yes, in several ways. First, dissemination of reports via the Web allows firms to communicate more easily and quickly with users than do traditional paper reports. In addition, Internet reporting allows users to take advantage of tools such as search engines and hyperlinks to quickly find information about the firm and, sometimes, to download the information for analysis, perhaps in computer spreadsheets. Finally, Internet reporting can help make financial reports more relevant by allowing companies to report expanded disaggregated data and more timely data than is possible through paper-based reporting. For example, some companies voluntarily report weekly sales data and segment operating data on their websites.

Given the widespread use of the Internet by investors and creditors, it is not surprising that organizations are developing new technologies and standards to further enable Internet financial reporting. An example is the increasing use of Extensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL). XBRL is a computer language adapted from the code of the Internet. It “tags” accounting data to correspond to financial reporting items that are reported in the statement of financial position, income statement, and the cash flow statement. Once tagged, any company's XBRL data can be easily processed using spreadsheets and other computer programs. In fact, XBRL is a global language with common tags across countries. As more companies prepare their financial reports using XBRL, users will be able to easily search a company's reports, extract and analyze data, and perform financial comparisons within industries and across countries.15