6.1 This photo was taken on a cloudy day, giving the scene a shadowless, soft light appearance. Exposure: ISO 100, f/1.8, 1/4000 second with a Sigma 35mm f/1.4 DG HSM.

Chapter 6: Working with Light

The word photography is derived from two Greek words: photos (light) and graphos (writing or painting). Without a doubt, light is the most essential ingredient that goes into making a photograph. Light is also the most variable part of the photographic equation because it can change instantly, either by the hand of the photographer or the force of nature. Ultimately, the way that light interacts with a subject is the defining factor of the tone and mood of an image.

Working with light, and learning to control and manipulate it, is one of the fundamental keys to becoming a successful photographer. If you allow light to control your photography, you will forever be at its mercy and never truly grasp the art of photography.

Controlling light is the key to setting the tone of your images.

Lighting Essentials

The way light interacts with a subject has an enormous effect on the way the camera records the image. The angle and direction from which the light is coming, as well as the color of the light source and the quality of the light, all play a part in the way the image appears. All of these things combined affect the mood, tone, and feeling of an image, so it’s important to grasp the basic tenets behind using light for photography. This section covers the two main types of lighting used by photographers and filmmakers today: Soft and hard light.

The quality of light

Photographers and filmmakers use the term quality of light to describe the way that light interacts with a scene. Quality doesn’t necessarily describe whether the light is good or bad, but rather, how it looks within the scene.

The first thing a photographer should consider when planning an image concept or assessing an existing light scene is the quality of light. For example, if you’re planning to shoot a portrait, you need to decide how you want to portray the person. If you’re shooting a landscape, think about what time of day the lighting is best for that particular terrain.

Soft lighting

Soft light is distributed evenly across the scene and appears to wrap around the subject. It comes from a large light source, and the shadows fade gradually from dark to light, which results in a subtle shadow edge transfer. This is a very desirable type of light to use in most types of photography, especially in portraiture. You can also create soft light by placing a light source close to the subject or by diffusing the light source, thereby mimicking a larger light source.

The term shadow edge transfer is used to describe how abruptly the shadows in images go from light to dark. This is the determining factor in whether light is soft or hard. Soft light has a smooth transition and hard light has a well-defined shadow edge transfer.

Soft light is very flattering to most subjects. It is used to soften hard edges and smooth out the features of a subject. Soft lighting can be advantageous for almost any type of photography, although in some instances it can lack the depth that you get from using a more direct light source.

To achieve soft lighting naturally, you can place the subject in an area that isn’t receiving direct sunlight, such as under a porch, overhang, or tree. Cloudy (especially partly cloudy) days are also ideal for soft, diffused lighting.

When artificial light is the source of your subject’s illumination, you usually need to modify the light in some way to make it soft. Redirecting or bouncing the light off a wall or some other reflective material softens the light; aiming the light source through diffusion material is also a good way to soften the light.

Hard lighting

The opposite of soft light is hard light. With hard light, the shadow edge transfer is more defined. It is directional, and you can pinpoint where the light source is located very easily. Moving the light source farther from the subject results in harder light because the light source becomes smaller relative to the subject.

Hard light isn’t used as extensively as soft light, but it is very effective in highlighting details and textures in almost any subject. Hard light is often used in landscape shots to bring attention to details in natural formations. Hard light is also effective for creating gritty or realistic portraits.

Artificial hard light is easily achieved with a bare light source. You can also use accessories, such as grids or snoots, to make the light more directional. The bright, midday sun is an excellent example of a natural, hard light source as shown in Figure 6.2.

6.2 This hard-light portrait was taken in direct sunlight. Exposure: ISO 100, f/1.8, 1/4000 second with a 28mm f/1.8G.

Lighting direction

The direction from which light strikes your subject has a major impact on how your images appear. When using an artificial light source, you can easily control the direction of the lighting by moving the light source relative to the subject. When using natural lighting, moving the subject relative to the light source is the key to controlling the lighting direction. I cover the three major types of lighting direction in the following sections.

Frontlighting

Frontlighting comes from directly in front of the subject, following the old photographer’s adage: keep the sun at your back. This is a good general rule; however, sometimes frontlighting can produce flat results lacking in depth and dimension. In Figures 6.3 and 6.4, you can see the difference that changing the direction of the light can have on a subject. When the light is aimed straight ahead, as shown in Figure 6.3, more of it reflects from the background, which brightens the background significantly, as well.

Frontlighting works pretty well for portraits, and many fashion photographers swear by it, especially for highlighting hair and makeup. Frontlighting flattens out facial features and also hides blemishes and wrinkles very well. Be aware that using frontlighting with a continuous light source, like the sun, can cause your subject to squint.

6.3 This vintage radio was lit from the front with an on-camera, SB-900 Speedlight. Notice that the lighting is flat and even. Exposure: ISO 400, f/4.0, 1/200 second with a 300mm f/4.0.

Sidelighting

Although sidelighting comes in from the side, it doesn’t necessarily have to come in from a 90-degree angle. It usually comes in from a shallower angle, such as 45 to 60 degrees.

Lighting the subject from the side increases the shadow contrast and causes the details to become more pronounced. This is what gives two-dimensional photographs a three-dimensional feel. Sidelighting is equally effective when using either hard or soft light, and it works for just about any subject.

6.4 The light was moved to the side for this shot. Notice that the radio has more texture, depth, and form, giving it more dimensionality and lending the image a somewhat moodier quality. Exposure: ISO 100, f/4.0, 1/200 second with a 300mm f/4.0.

Backlighting

Backlighting involves placing the light source behind the subject. Although it’s not as common as front- and sidelighting, it does have its uses. Backlighting is often used in conjunction with other types of lighting to add highlights to the subject.

Using backlighting and lens flare creates a classic, cinematic effect.

Backlighting has often received a bad rap in photography, but more photographers are now using it to add artistic flair to their images. Backlight introduces effects that were once perceived as undesirable in classical photography, such as lens flare and decreased contrast. Photographers today are discovering that, when used correctly, backlighting can create interesting images.

The key to making backlighting work is to use the Spot metering mode (![]() ). When shooting portraits, meter on the subject; for silhouettes, meter on the brightest area in the scene.

). When shooting portraits, meter on the subject; for silhouettes, meter on the brightest area in the scene.

Backlighting can make portraits more dynamic, incorporate silhouettes into landscape photos, or make translucent subjects, like the flowers shown in Figure 6.5, seem to glow.

6.5 Backlighting can add lens flare to your image, giving it a cinematic effect. Exposure: ISO 400, f/8.0, 1/2000 second, using an 80-200mm f/2.8D at 80mm.

Natural Light

Natural light is probably the easiest light source to find simply because it’s all around you, as the sun is the source of all natural light. Some people confuse available light with natural light. To make it clear, all natural light is available light, but not all available light is natural light. Available light is light that exists in a scene and that isn’t augmented by the photographer. For example, when you walk into a room that is solely lit with an overhead lamp, the overhead lamp provides the available light, but it is not natural light.

Early in the morning and late in the evening when the sun is rising or setting are the best times to take photographs. These times are known as the Golden Hour.

That being said, natural light can be the most difficult to work with. It can be too harsh on a bright, sunny day, too unpredictable on a partly cloudy day, and although an overcast day can provide beautiful soft lighting, it can sometimes lack definition, which leads to flat images.

Natural light often benefits from some sort of modification to make it softer and less directional. Here are a few examples of natural lighting techniques:

• Use fill flash. As contrary as it sounds, using flash to augment natural light can really help. You can use the flash as a secondary light source (not as your main light) to fill in the shadows and reduce contrast.

• Try to use window lighting. Like fill flash, this technique is one of the best ways to use natural light, even though it seems contrary. Go indoors and place your model next to a window. This provides a beautiful soft light that is very flattering. Many professional portrait and food photographers use window light. It can be used to light almost any subject softly and evenly, yet it still provides directionality. This is definitely the quickest, and often the nicest, light source you can find.

6.6 Window lighting was all that was necessary for this food shot. Exposure: ISO 640, f/4.5, 1/50 second, using a Sigma 17-70mm f/2.8-4 DC HSM OS at 28mm.

• Find some shade. The shade of a tree or the overhang of an awning or porch can block the bright sunlight while still providing plenty of diffuse light with which to light your subject.

• Take advantage of clouds. A cloudy day softens the light, allowing you to take portraits outside without worrying about harsh shadows and too much contrast. If it’s only partly cloudy, you can wait for a cloud to pass over the sun before taking your shot.

• Use a modifier. Use a reflector to reduce the shadows, or a diffusion panel to block the direct sunlight from your subject.

Continuous Light

Continuous lighting is a constant light source. It has a what you see is what you get effect, therefore, it’s the easiest type of lighting to use. You can set up the lights and see what effect they have on your subject before you even pick up your D5200. Continuous lights are an affordable option for a beginners, and the learning curve isn’t too steep.

As with other lighting systems, you have many continuous lighting options. Here are a few of the most common:

• Incandescent. Incandescent, or tungsten, lights are the most common type of lights (a standard light bulb is a tungsten lamp). With tungsten lamps, an electrical current runs through a tungsten filament, heating it and causing it to emit light. This type of continuous lighting is the origin of the term hot lights.

• Halogen. Halogen lights, which are much brighter than typical tungsten lights, are another type of hot light. Considered a type of incandescent light, halogen lights employ a tungsten filament, but they also include halogen vapor in the gas inside the lamp. The color temperature of halogen lamps is higher than the color temperature of standard tungsten lamps. Halogen lights are also more expensive and the lamps burn much hotter than standard light bulbs.

• Fluorescent. Fluorescent lighting is used in most office buildings and retail stores. In a fluorescent lamp, electrical energy changes a small amount of mercury into a gas. The electrons collide with the mercury gas atoms, causing them to release photons, which in turn cause the phosphor coating inside the lamp to glow. Because this reaction doesn’t create much heat, fluorescent lamps are much cooler and more energy efficient than tungsten and halogen lamps. In the past, fluorescent lighting wasn’t commonly used because of the ghastly green cast the lamps caused. These days, with color-balanced fluorescent lamps and the ability to adjust white balance, fluorescent light kits for photography and especially video are becoming more common and are very affordable.

Here are some disadvantages of using incandescent lights:

• Color temperature inconsistency. The color temperature of lamps change the more they are used and as the current varies. The color temperature may be inconsistent from manufacturer to manufacturer and may even vary within the same types of bulbs.

• Light modifiers are more expensive. Because most continuous lights are hot, modifiers such as softboxes need to be made to withstand the heat; this makes them more expensive than the standard equipment intended to be used for strobes.

• Short lamp life. Incandescent lights tend to have a shorter life than flash tubes, so you must replace them more often.

If you’re serious about continuous lighting, you may want to invest in a photographic light kit. These kits are widely available from any photography or video store. They usually include both the lights and light stands. Some kits also include light modifiers (such as umbrellas or softboxes) to diffuse the light and create a softer look. The kits can be relatively inexpensive, with two lights, two stands, and two umbrellas costing around $100. You can buy much more elaborate setups that cost all the way up to $2,000.

The D5200 Built-in Flash

The Nikon D5200 has a built-in flash that pops up for quick use in low-light situations. Although this little flash is fine for snapshots, it’s not always the best option for portraying your subject in a flattering light.

Even when you’re using the pop-up flash for snapshots, I recommend using a pop-up flash diffuser. There are a number of brands and types, but I use a LumiQuest Soft Screen. It folds up flat to fit in your pocket and costs a little over $10.

Built-in flash exposure modes

The built-in flash of the D5200 has a few different exposure modes that control the way the flash calculates exposure, flash output, and brightness, and a couple of modes for using some advanced flash techniques.

i-TTL and i-TTL BL

The D5200 determines the proper flash exposure automatically using Nikon’s proprietary i-TTL (Intelligent-Through-the-Lens) flash metering system. The theory behind i-TTL is the same as standard exposure metering, except that, with i-TTL, the camera gets most of the metering information from monitor preflashes emitted from the flash. These preflashes emit almost simultaneously with the main flash, so it almost appears as if the flash only fires once. The camera also uses data from the lens, such as distance information and f-stop values, to help determine the proper flash exposure.

Additionally, the D5200 employs two types of i-TTL flash metering: Standard i-TTL flash and i-TTL Balanced Fill-Flash. With Standard i-TTL flash mode, the camera determines the exposure for the subject only and doesn’t consider the background lighting. With i-TTL Balanced Fill-Flash mode, the camera attempts to balance the light from the flash with the ambient light to produce a more natural-looking image.

When you use the built-in flash on the D5200, the default mode is i-TTL Balanced Fill-Flash when using the Matrix (![]() ) or Center-weighted (

) or Center-weighted (![]() ) metering modes. When the D5200 is set to Spot metering (

) metering modes. When the D5200 is set to Spot metering (![]() ), the flash defaults to i-TTL automatically.

), the flash defaults to i-TTL automatically.

Manual

The built-in flash power is set by fractions in Manual mode (![]() ), with 1/1 being full power. The output is halved for each setting (which is equal to 1 stop of light). The settings are 1/1, 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, and 1/32.

), with 1/1 being full power. The output is halved for each setting (which is equal to 1 stop of light). The settings are 1/1, 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, and 1/32.

The Guide Number (GN) for the built-in flash is 39 when measuring distance in feet, or 12 when using meters at full power (1/1) set to ISO 100. To determine the GN at higher ISO settings, multiply the GN by 1.4 for each stop that the ISO increases. For example, doubling the ISO setting to 200 increases the GN by a factor of 1.4, so GN 39 × 1.4 = GN 54.6.

Similarly, when reducing the flash power by 1 stop, you divide the GN by a factor of 1.4, so at 1/2 power, the GN is about 28 (GN 39 ÷ 1.4 = GN 27.8).

Flash sync modes

Flash sync modes control how the flash operates in conjunction with your D5200. These modes work with both the built-in Speedlight and accessory Speedlights, such as the SB-910, SB-700, SB-600, and so on. These modes allow you to choose when the flash fires, either at the beginning of the exposure or at the end, and they also allow you to keep the shutter open for longer periods, enabling you to capture more ambient light in low-light situations. However, before covering the Sync modes, I need to explain sync speeds.

Sync speed

The sync speed is the fastest shutter speed that you can use while achieving a full flash exposure. This means that if you set the shutter speed faster than the rated sync speed of the camera, you end up with a partially exposed image (the image will appear with a black bar at the bottom). The D5200 won’t let you set the shutter speed above the rated sync speed of 1/200 second when using the built-in flash or a dedicated Speedlight. This means you don’t need to worry about having partially black images when using a Speedlight, but it may be something to consider if you use studio-type flash units.

Limited sync speeds exist because of the way shutters work in modern cameras. All dSLR cameras have a focal plane shutter. This shutter is located directly in front of the focal plane, which is the surface of the sensor. The focal plane shutter has two shutter curtains that travel vertically in front of the sensor to control the time the light can enter through the lens. At slower shutter speeds, the front curtain covering the sensor moves away, exposing the sensor to light for a set amount of time. When you have made the exposure, the second curtain moves in to block the light, thus ending the exposure.

To achieve shutter speeds faster than 1/200 second, the second curtain of the shutter starts closing before the first curtain has exposed the sensor completely. This means the sensor is actually exposed by a slit that travels along the height of the sensor. This allows your camera to have extremely fast shutter speeds, but it limits the flash sync speed because the entire sensor must be exposed to the flash at once to achieve a full exposure.

Front-curtain sync

Front-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ) is the default for your camera when you use the built-in flash or one of Nikon’s dedicated Speedlights. In Front-curtain sync flash mode (

) is the default for your camera when you use the built-in flash or one of Nikon’s dedicated Speedlights. In Front-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ), the flash fires as soon as the shutter’s front curtain fully opens. This mode works well with most general flash applications.

), the flash fires as soon as the shutter’s front curtain fully opens. This mode works well with most general flash applications.

When you set the Shooting mode to Programmed auto (![]() ) or Aperture-priority auto (

) or Aperture-priority auto (![]() ), the shutter speed is set to 1/60 second automatically.

), the shutter speed is set to 1/60 second automatically.

Front-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ) works well when you use relatively fast shutter speeds. However, if you use Shutter-priority auto mode (

) works well when you use relatively fast shutter speeds. However, if you use Shutter-priority auto mode (![]() ) and the shutter speed is slowed down to 1/30 or slower (also known as dragging the shutter in flash photography), Front-curtain sync flash mode (

) and the shutter speed is slowed down to 1/30 or slower (also known as dragging the shutter in flash photography), Front-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ) causes your images to have an unnatural-looking blur in front of them. This occurs especially when photographing a moving subject because the ambient light reflects off of it.

) causes your images to have an unnatural-looking blur in front of them. This occurs especially when photographing a moving subject because the ambient light reflects off of it.

When doing flash photography, your camera actually records two exposures concurrently: The flash exposure and the ambient light. When you use a faster shutter speed in lower light, the ambient light usually isn’t bright enough to have an effect on the image. When you slow down the shutter speed substantially, it allows the ambient light to be recorded to the sensor, causing ghosting. Ghosting is a partial exposure that usually appears transparent on the image.

6.7 Front-curtain sync flash mode creates an unnatural looking blur when dragging the shutter during flash exposures. Exposure: ISO 800, f/5.0, 1 second with a 50mm f/1.8G.

Ghosting causes a trail to appear in front of the subject because the flash freezes the initial movement of the subject. Because the subject is still moving, the ambient light records it as a blur that appears in front of the subject, creating the illusion that it’s moving backward. To counteract this problem, you can use Rear-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ), which I explain later.

), which I explain later.

Slow sync

When doing flash photography at night, your subject is often lit well, but the background appears completely dark. Slow sync flash mode (![]() ) helps take care of this problem because it allows you to set a longer shutter speed (up to 30 seconds) to capture some of the ambient light of the background. This allows the subject and the background to be more evenly lit, and you can achieve a more natural-looking photograph.

) helps take care of this problem because it allows you to set a longer shutter speed (up to 30 seconds) to capture some of the ambient light of the background. This allows the subject and the background to be more evenly lit, and you can achieve a more natural-looking photograph.

To avoid ghosting in Slow sync flash mode (![]() ), be sure that the subject remains still for the whole exposure. With longer exposures, you can use ghosting creatively.

), be sure that the subject remains still for the whole exposure. With longer exposures, you can use ghosting creatively.

Red-Eye Reduction

When using on-camera flash, such as the built-in flash, you often get the red-eye effect. This occurs because the pupils are wide open in the dark, and the light from the flash is reflected off the retina and back to the camera lens. Fortunately, the D5200 offers a Red-Eye Reduction mode (![]() ). When you activate this mode, the camera either turns on the AF-assist illuminator (when using the built-in flash) or fires some preflashes (when using an accessory Speedlight), which causes the pupils of the subject’s eyes to contract. This reduces the amount of light from the flash that reflects off the retina, thus reducing or eliminating the red-eye effect.

). When you activate this mode, the camera either turns on the AF-assist illuminator (when using the built-in flash) or fires some preflashes (when using an accessory Speedlight), which causes the pupils of the subject’s eyes to contract. This reduces the amount of light from the flash that reflects off the retina, thus reducing or eliminating the red-eye effect.

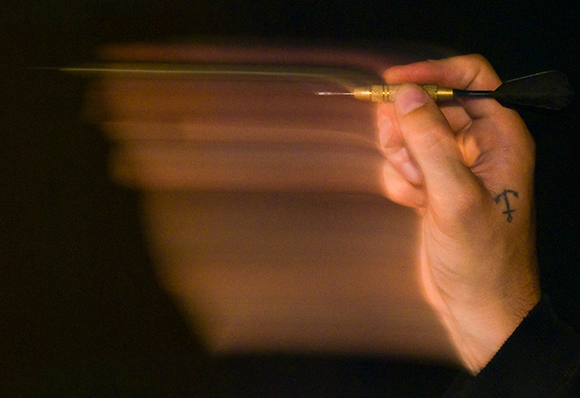

Rear-curtain sync

When using Rear-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ), the camera fires the flash at the end of the exposure just before the rear curtain of the shutter starts moving. This is useful when you’re taking flash photographs of moving subjects. Rear-curtain sync flash mode (

), the camera fires the flash at the end of the exposure just before the rear curtain of the shutter starts moving. This is useful when you’re taking flash photographs of moving subjects. Rear-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ) allows you to portray the motion of the subject more accurately by causing a motion blur trail behind the subject rather than in front of it, as is the case with the Front-curtain sync flash mode (

) allows you to portray the motion of the subject more accurately by causing a motion blur trail behind the subject rather than in front of it, as is the case with the Front-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ). You can also use Rear-curtain sync flash mode (

). You can also use Rear-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ) in conjunction with the Slow sync flash mode (

) in conjunction with the Slow sync flash mode (![]() ) to achieve Slow Rear-curtain sync flash mode (

) to achieve Slow Rear-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ).

).

6.8 Rear-curtain sync flash mode gives the image a more natural sense of movement with the blur following behind the subject. Exposure: ISO 800, f/5.0, 1 second with a 50mm f/1.8G.

Rear-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ) is available in all of the exposure modes: Programmed auto (

) is available in all of the exposure modes: Programmed auto (![]() ), Shutter-priority auto (

), Shutter-priority auto (![]() ), Aperture-priority auto (

), Aperture-priority auto (![]() ), and Manaul (

), and Manaul (![]() ). Slow Rear-curtain sync flash mode (

). Slow Rear-curtain sync flash mode (![]() ) is available only in the Programmed auto (

) is available only in the Programmed auto (![]() ), Auto (

), Auto (![]() ), or Auto Flash off (

), or Auto Flash off (![]() ) modes.

) modes.

Flash Compensation

When you photograph subjects using flash, whether you’re using the built-in flash on your D5200 or an external Speedlight, there may be times when the flash causes your principal subject to appear too light or too dark. This usually occurs in difficult lighting situations, especially when you use i-TTL metering. Your camera’s meter can be fooled into thinking the subject needs more or less light than it actually does. This can happen when the background is very bright or very dark, or when the subject is off in the distance or very small in the frame.

Flash compensation allows you to adjust the flash output manually, while retaining the i-TTL readings so your flash exposure is at least in the ballpark. With the D5200, you can vary the output of your built-in flash’s TTL setting (or your own manual setting) from –3 Exposure Value (EV) to +1 EV. This means that if your flash exposure is too bright, you can adjust it down 3 full stops under the original setting. If the image seems underexposed or too dark, you can adjust it to be brighter by 1 full stop.

Press the Flash compensation (![]() ) and Exposure compensation (

) and Exposure compensation (![]() ) buttons simultaneously, and rotate the Command dial to apply flash compensation.

) buttons simultaneously, and rotate the Command dial to apply flash compensation.

Creative Lighting System Basics

The Creative Lighting System (CLS) is what Nikon calls its proprietary system of Speedlights and the technology that goes into them. The best part of CLS is the ability to control Speedlights wirelessly, which Nikon refers to as Advanced Wireless Lighting (AWL). AWL allows you to get your Speedlights off-camera so that you can control light placement like a professional photographer would with studio-type strobes.

To take advantage of AWL, all you need is your D5200, a Speedlight that can be used as a Commander (such as the current SB-910, SB-700, or SU-800, or the discontinued SB-800 or SB-900), and at least one remote Speedlight (such as the current SB-910, SB-700, SB-600, or SBR-200, or the discontinued SB-800 or SB-900).

Communications between the commander flash and the remote units are accomplished by using pulse modulation. Pulse modulation means that the commanding Speedlight fires rapid bursts of light in a specific order. The pulses of light are used to convey information to the remote group, which interprets the bursts of light as coded information. The commander tells the other Speedlights in the system when and at what power to fire. You can also use an SB-700, SB-800, SB-900, or SB-910 Speedlight or an SU-800 Commander as a master. This allows you to control three separate groups of remote flashes and gives you an extended range.

The Nikon SB-400 cannot be used as a remote unit.

In a nutshell, this is how the Creative Lighting System works:

1. The commander unit sends instructions to the remote groups to fire a series of monitor preflashes to determine the exposure level. The camera’s i-TTL metering sensor reads the preflashes from all the remote groups and takes a reading of the ambient light.

2. The camera tells the commander unit the proper exposure readings for each group of remote Speedlights. When the shutter is released, the commander, via pulse modulation, relays the information to each group of remote Speedlights.

3. The remote units fire at the output specified by the camera’s i-TTL meter, and the shutter closes.

All of these calculations happen in a fraction of a second, as soon as you press the shutter-release button. It almost appears to the naked eye as if the flash just fires once. There is little lag-time waiting for the camera and the Speedlights to do the calculations.

Light Modifiers

When you set up a photographic shot, you are building a scene using light. For some images, you may want a hard light that is very directional; for others, a soft, diffused light works well. Light modifiers allow you to control the light so you can direct it where you need it, give it the quality the image calls for, and even add color or texture to the image. There are many kinds of diffusers, but the following are the most common:

• Umbrella. The photographic umbrella is used to soften the light. You can either aim the light source through the umbrella or bounce the light from the inside of the umbrella, depending on the type of umbrella you have. Umbrellas are very portable and make a great addition to any Speedlight setup.

6.9 A Nikon Speedlight with an umbrella.

• Softbox. These also soften the light and come in a variety of sizes, from huge 8-foot softboxes to small 6-inch versions that fit right over your Speedlight mounted on the camera.

6.10 A medium-sized softbox.

• Reflector. These are probably the handiest modifiers you can have. You can use them to reflect natural light onto your subject or to bounce light from your Speedlight onto the subject, making it softer. Some can act as diffusion material to soften direct sunlight. They come in a variety of sizes from 2 to 6 feet and fold up into a small, portable size. I recommend that every photographer have a small reflector in his or her camera bag.

6.11 A small reflector being used to bounce light from a Speedlight.