Chapter 11

Minority Squeeze-Outs

Some of the worst shareholder abuses can be found when a majority owner of a public company seeks to buy out the minority shareholders. The majority owner controls all of the information flow and has an advantage over the outside shareholders that is similar to that enjoyed by management in a management buyout. In fact, the majority shareholder often controls management because it has majority control of the board.

Due to this control, the target company does not operate as an independent business. The larger the proportion of shares held by the majority stockholder, the more the company resembles a subsidiary of the majority shareholder. In many cases, it actually acts economically as a subsidiary, in that most of its business is done with the majority shareholder or it sells products or services that are extensions of the offerings of the majority shareholder. Therefore, minority squeeze-outs are frequently referred to as parent-subsidiary mergers, in which the subsidiary has publicly traded minority interests. Statutory squeeze-outs have already been discussed in the context of two-step offers. As a reminder, in the first step of a takeover offer the acquirer aims to obtain a sufficient number of shares so that minority shareholders who have not tendered can then be squeezed out through a statutory squeeze out in a second step. As a result the acquirer obtains full control of the target. The threshold that an acquirer needs to obtain in order to squeeze out minority shareholders involuntarily varies by jurisdiction, but generally is either 90 or 95 percent almost everywhere around the world. Table 11.1 shows a list of the threshold in select countries. It should be noted that for companies that are incorporated in one country and listed in a second the applicable squeeze-out regulation is that of the country of incorporation.

Table 11.1 Squeeze-Out Thresholds around the World

| Country | Threshold (percent) |

| Austria | 90 |

| Australia | 90 |

| Belgium | 95 |

| China | Not allowed |

| France | 95 |

| Germany | 95; 90* |

| Hong Kong | 90 |

| Italy | 95; 90 unless free float sufficient to ensure trading is restored within 90 days |

| Netherlands | 95 |

| Spain | 90 |

| Switzerland | 90 in connection with a merger; otherwise 98 |

| United Kingdom | 90 |

* Three different laws govern squeeze-outs. Two laws (§327a AktG and §39a WpÜG) have a 95 percent threshold, whereas since the year 2011, a simplified squeeze out (§ 62 UmwG) can be effected above a 90 percent level.

Of interest for this chapter are squeeze-outs in which the majority shareholder has not yet reached the threshold level at which it can effect a statutory squeeze-out of the remaining investors. In such cases it is not unusual to see some of the worst shareholder abuse.

Protections for minority investors vary between jurisdictions. Continental Europe has developed the mechanism of domination and profit sharing agreements. In the United States, there is little to no statutory protection and shareholders can rely only on general fiduciary standards.

Domination and Profit Sharing Agreements

A particularity of several continental European countries (Germany, Austria, Switzerland), Domination and Profit Sharing Agreement are a formal way to transfer control of a company to its majority shareholder while minority interests continue to hold an ownership stake. These agreements are concluded once an acquirer has reached 75 percent ownership of a target in a tender offer. They are a common feature in post-merger company integration. For a minority shareholder they offer an optionality that can offer an interesting risk/return profile.

The ultimate goal of most acquirers is to obtain full control of the target firm. However, when it is not yet possible to squeeze out the minority a domination and profit sharing agreement transfers control to the acquirer and provides it with a similar economic benefit as full control—but for the continued minority stake.

At the time a domination and profit sharing agreement is entered the acquirer has to obtain an independent valuation of the company and cash out any shareholders who seek liquidity. Shareholders who continue to hold their shares have the right to receive a minimum annual dividend payment and can redeem their shares at any time at the valuation determined at the time of the conclusion of the agreement. Exhibit 11.1 shows the domination and profit sharing agreement concluded between Celesio AG and the acquirer McKesson, which concluded the agreement through a subsidiary named Dragonfly. It can be seen that the valuation of the shares was €22.99 per share, while the annual dividend amounted to €0.83 per share. These numbers are arrived at by an independent expert who has been retained by the company.

It is common that the valuation reached in connection with a domination and profit sharing agreement is challenged in court proceedings known as Spruchverfahren. This litigation frequently leads to valuations in excess of what the company's expert determined at the time of the conclusion of the domination agreement. However, these cases can take several years to complete, so that arbitrageurs incur considerable timing risk.

Domination and profit sharing agreements generally are followed at a later time by the squeeze-out of minority shareholders. For that to happen, the controlling shareholder needs to reach 90 or 95 percent of shareholdings. Astute observers follow open market purchases of controlling shareholders to estimate whether a controlling shareholder is getting closer to the squeeze-out mark. However, there is no requirement that a domination and profit-sharing agreement must be followed by a squeeze-out. In principle, it is possible that a small free float remains outstanding indefinitely.

U.S. Minority Shareholders

Minority shareholders in the United States have relatively fewer and weaker options to protect themselves against unfair treatment in a squeeze-out transaction or against abuse by majority shareholders generally. To complicate matters, regulations vary from state to state, although Delaware is, as in many other aspects of corporate law, the point of reference.

Under Delaware rules, because the majority shareholder already controls the majority of the company, there is no change in control, and the protection of Revlon duties (see Chapter 8) does not apply. The board is not obligated to maximize the price that shareholders will receive.

Nevertheless, minority squeeze-outs are subject to an entire fairness standard. The board only has to ensure that the buyout price is fair, not that it is maximized. However, it is difficult to demonstrate entire fairness when the buyer controls the board. Boards should take two measures to alleviate the concern over the buyer's control:

- A special committee of independent directors should negotiate with the majority holder on behalf of the minority shareholders.

- The closing should be conditioned on the acceptance by a majority of the minority shareholders.

Delaware courts will assume that if these two conditions are met, the squeeze-out of minority shareholders was fair. As I pointed out in Chapter 8, fairness is a procedural concept, not one that sets definitive price levels.1 The principal drawback of this assumption is that neither of the two conditions deals with fairness of price. The price might not be fair, but might be large enough to be acceptable to just enough shareholders that a majority of the minority is attained. It is perfectly conceivable that an independent committee negotiates too low a price, and a majority of shareholders accepts it for fear of holding an otherwise illiquid position as minority shareholders in a firm of which the majority shareholder takes advantage through related party transactions. Just because a majority of the minority has accepted the offer, one cannot conclude that the squeeze-out was not coercive. The opposite may well be the case: If minority shareholders participate in the offer to a large degree, then that may be a sign of coercion.

Coercion can come in many forms; for example, if the target company generates losses, then minority shareholders have an interest in selling their shares sooner rather than later, especially if the losses are expected to increase. The subsidiary may eventually end up in bankruptcy and may then be rescued by the majority shareholder, especially if it is of strategic important to its core business. However, minority shareholders probably would be wiped out in the rescue operation. Another form of coercion is the absence of an alternative to the squeeze-out. Minority shareholders remain at the mercy of the majority shareholder unless they tender their shares. Therefore, any proposal to buy out the minority shareholders will be coercive. The coercion occurs in a more subtle way what than the courts would attach that label to.

Even if one denies the existence of coercion, there is no doubt that many minority shareholders are frustrated if they hold shares in a company that is controlled by a self-interested majority investor. I have seen time and time again that frustrated shareholders will accept any deal, even a bad one, just to be able to get out of the position and move on. Stocks with a large majority shareholder generally have limited liquidity. Shareholders find it difficult to sell without driving down the price. If a majority holder makes a squeeze-out proposal, it constitutes the only liquidity event available to the minority shareholders. Under these circumstances, a bad deal may appear to be better than no deal.

Boards' Lack Effectiveness during Squeeze-outs

Similarly, the existence of a special committee of independent directors is in itself not necessarily evidence of a fair process. Many supposedly “independent” directors are beholden to management in one way or another. The standards applied to board members to verify their independence are very loose. Even family members are considered independent. In the case of Wilshire Enterprises, the cousin of the chief executive officer (CEO) was deemed to be independent under rules of what was then the American Stock Exchange. Rarely are independent directors completely detached from the majority shareholder. They were often invited to join the board by management, sometimes by that of the majority shareholder. They may work in the same industry that the majority shareholder is in. In any case, independent directors will have relationships of some sort with the majority shareholder and will find it difficult to take a confrontational stance for fear of antagonizing the majority shareholder. The world of board directors is a small one, and board positions are lucrative and prestigious. No independent director will risk jeopardizing future board appointments by being seen as too independent and working against the interest of the majority holder, even if doing so benefits the minority shareholders. The real world is much more complex than the Delaware courts' idealized role of independent directors who are completely detached from social interactions. As long as board members are humans, there will always be a structural bias in committees composed of independent directors.

The mere presence of a special committee also can serve as a charade to mask an entirely unfair process. Committee members must be engaged in the process and actively defend the interests of the minority shareholders. A committee that merely rubber-stamps decisions of the majority shareholder can hardly be regarded as evidence of a fair process. A further complication is the absence of a sufficiently large number of independent directors on the board of the subsidiary.

Directors serving on a special committee created to negotiate a merger are compensated for their extra effort and time. In addition, paying them is supposed to align their interests with those of shareholders. These payments are made in addition to regular directors' fees.

Corporate governance firm the Corporate Library conducted a study of payments to members of special committees in merger and acquisition situations and found that a flat fee is the most common form of compensation.2 Flat fees at the firms in its study varied between $10,000 and $75,000 with a median of $27,500. Directors who receive fees only for attending meetings of the special committee receive between $500 and $10,500 per meeting, with a median of $750. Other forms of payments are retainers—one time or monthly—combined with per-meeting fees. Monthly retainers range from $5,000 to $12,500. Chairs of the special committee receive higher retainers and per-meeting fees in roughly 40 percent of all cases. These figures are likely to have increased since the year 2006 when the study was conducted. Unfortunately, the study did not try to correlate payments to committee members with committee effectiveness in the buyout process.

Once a majority shareholder begins negotiations with a special committee, two implicit assumptions are made:

- There will eventually be a sale of the minority interests.

- The majority holder will be the buyer who will be successful in acquiring the shares held by the minority.

In instances where the board of the target takes its responsibilities seriously, its efforts will be frustrated by these two constraints. The target is, after all, a subsidiary of the majority shareholder, and it is hard to fathom another firm acquiring a minority stake in its competitor's subsidiary. Similarly, financial buyers seek control of the target firm and have no interest in a minority position in a subsidiary. Private equity funds often do acquire subsidiaries of larger firms; when they do so, however, they acquire control of the subsidiary.3

Minority Shareholders Are in a Tough Spot

Courts assume that in a tender offer, there is no coercion by the majority shareholder if the offer is conditioned on the acceptance by the majority of the minority. In the absence of coercion, the process is deemed fair.

The travesty of the majority of the minority rule in tender offers becomes clear from the 2002 acquisition of Siliconix by its 80.4 percent majority shareholder, Vishay Intertechnology. The independent committee of Siliconix was dragging its feet on Vishay's squeeze-out proposal, attempting to negotiate a better price. Vishay was unwilling to increase its price. The market, meanwhile, voted by bringing Siliconix's trading price above Vishay's proposed price. Unable to negotiate a merger on its terms, Vishay launched a stock-for-stock tender offer. The exchange ratio was based on the prices of Siliconix and Vishay after Vishay's first tender offer. In other words, the buyout premium had all but vanished.

Invariably, a majority of minority shareholders accepted the terms of the deal and tendered. The committee of independent directors did not support the transaction but adopted a neutral stance. In the shareholder litigation that followed, the court maintained that because a majority of the minority shareholders had tendered their shares without coercion and the committee of independent directors had not objected, the transaction was fair from a procedural point of view.4

The situation would have been different had there been no special committee of independent directors or no clause requiring the majority of the minority shareholders to tender their shares. The acquisition of ARCO Chemical by Lyondell Petrochemical Company5 was structured as a merger, and the court ruled that

[…] the board cannot abdicate [its] duty by leaving it to the shareholders alone to approve or disprove [sic] the merger agreement because the majority shareholder's voting power makes the outcome a preordained conclusion.

For the Delaware court, the difference between a tender offer and a merger is that in a tender offer, shareholders have the ability not to tender and thereby derail the transaction. In a merger, once the majority holder votes in favor, the transaction will close irrespective of whether the outside shareholders support it.

Since the Siliconix ruling, this standard has been read to apply only to mergers. Under current Delaware law, companies are free to squeeze out minority shareholders through tender offers at unfair prices. The buyer only faces the disclosure requirements of Schedule 13E-3, where the buyer must explain why the transaction is procedurally fair to minority shareholders. As discussed in Chapter 9, the disclosure always states that the buyer believes that the transaction is fair.

Another strategy for a majority shareholder is to acquire shares in the open market until it reaches the threshold at which it can conduct a short form merger. The only risk with that strategy is that it must report its purchases on Schedule 13D or 13G, thus notifying the market of its actions and potentially triggering a rally in the stock price. The higher the percentage owned by the majority owner, the more likely such a strategy is to succeed. Open market purchases take time to effect. If only a small position is to be acquired, the purchase can be completed before the deadline for the filing.

The implications for shareholders of companies that have a controlling shareholder are potentially devastating. Companies that are controlled by a majority shareholder typically trade at a discount to comparable firms that have a well-diversified shareholder base. The market takes the risk of shareholders suffering at the hands of the majority shareholder into account in setting the prices at which shares trade. Shares will trade at a discount to their value absent this risk. Clearly, the market works efficiently in a micro sense, because the risk associated with the control by the majority shareholder is incorporated in the stock price. However, on a macro scale, it is a waste of capital if shareholders do not get the full value of their investment.

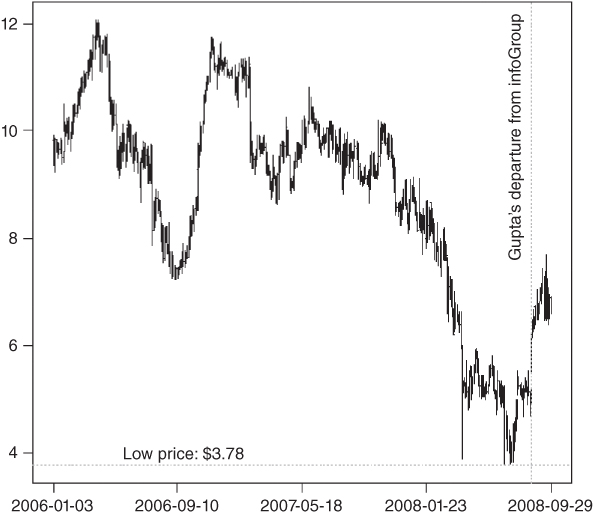

The experience of infoUSA (since renamed to infoGroup) shareholders illustrates the difficulties that minority shareholders encounter. InfoUSA's founder and CEO Vinod Gupta owned 37.5 percent of the company in 2005 when he made a proposal to buy out the public shareholders for $11.75 per share for a total transaction value of $390 million. He had been buying shares in the open market prior to his acquisition proposal and had stated that he believed himself that the shares were worth at least $18 per share6 and that he would acquire more shares in the future. The timing of the proposal was highly suspicious: It came only days after an earnings release had led to a drop in the stock price by more than 20 percent (see Figure 11.1). A special committee of independent directors was formed and rejected the proposal in August 2005. It presented Gupta with two alternatives: Either let the board conduct a market check to find what price other buyers may be willing to pay for infoUSA, or Gupta could negotiate with the special committee under an exclusivity arrangement, but he would have to accept a market check after the signing of a merger agreement. When confronted with these alternatives, Gupta withdrew his acquisition proposal. The special committee of the board was disbanded in a split vote.

Figure 11.1 Stock Price of infoUSA after the 2005 Earnings Release and Gupta's Acquisition Proposal

The end of the formal buyout negotiations did in no way stop Gupta's attempt to acquire control of the firm. InfoUSA had a poison pill in place that prevented any shareholder from acquiring more than 15 percent of the firm. However, Gupta was exempt from the poison pill and could acquire more shares. He had two methods at his disposal to obtain more shares: open market purchases, which he was doing already, and the exercise of executive options that he received as part of his CEO compensation package. Instead of buying infoUSA in one single transaction, Gupta could take control of the firm in a creeping takeover by increasing his ownership percentage through his option holdings and open market purchases.

Gupta took advantage of his options to increase his holdings when dissent from shareholders emerged prior to the 2006 shareholder meeting. An activist hedge fund, Dolphin Limited Partnership, was dissatisfied with the continued lackluster performance of infoUSA's stock and attempted to have its own nominees elected to the board in a contested election. Just prior to the record date for the shareholder meeting, Gupta exercised some of his options and hence boosted his holdings in the firm by 1.2 million shares to 40 percent. As a result of this increase in share ownership, infoUSA's director nominees were elected in the contest by a narrow margin with 51 percent of the votes. Gupta's share ownership was likely to increase even further: Between 2004 and 2007, he was the recipient of all of the company's stock awards. In 2007, a new stock option plan was put to a vote by shareholders that would have increased his holdings by another 3.5 million shares, equivalent to 6 percent of the shares.

Shareholders had another reason to be suspicious: Gupta's holdings reported prior to the contested director election to the Securities and Exchange Commission did not include all of his shares, and over 150 transactions were not reported. It was only after Dolphin initiated the proxy contest that Gupta's shares and the missing transactions were reported. To make matters worse, it was discovered later through litigation initiated by Dolphin that Gupta never intended to acquire the company. He stated in a September 2005 letter to that board:

After we lowered our revenue guidance due to the Donnelly Market shortfall, our stock got crushed. At that time I had no choice but to support the stock. That was the primary reason for offering $11.75 for the shares. If you recall, the stock had dropped to $9.20 per share. After my offer, even though it has been withdrawn, the stock is hanging in around $10.80 per share. Under the circumstances, nobody can sell their shares short because they know I am there to support it.

September 7, 2005, letter by Vinod Gupta to the Board released by Dolphin Limited Partnership on www.iusaccountability.com.

Dolphin's litigation also turned up many instances where Gupta's personal expenses appeared to have been paid by infoUSA, such as an 80-foot yacht for which no evidence of corporate usage was found, personal use of company jet, and a skybox.

The overall effect of these revelations was that confidence in infoUSA waned. Shareholders saw a dual threat from a creeping takeover by Gupta. In an attempt to alleviate these concerns, Gupta entered into a one-year standstill agreement in July 2006 under which he agreed not to acquire any additional shares. The agreement was subsequently extended by another year through 2008. But the market had already voted with its feet: infoUSA's stock declined (see Figure 11.2) to a low of $3.78 in 2008. It was only after Gupta's departure as CEO in August 2008 that the trend in the stock's performance reversed. Nevertheless, while Gupta controlled over 40 percent of the shares, the company remained a highly risky investment, and shareholders had to accept a low valuation for their shares to compensate for the risk associated with a majority shareholder.

Figure 11.2 infoUSA's Stock Price, 2006–2008

Gupta was never actually a majority holder of infoUSA in the sense that his ownership never exceeded 50 percent. Nevertheless, his holdings were large enough to make him a de facto majority holder:

- His holdings amounted to 40 percent, giving him the largest single vote.

- As beneficiary of the stock option plan, he was slowly increasing his holdings to the 50 percent level.

- In contested board elections, candidates backed by management won even though the vast majority (roughly 90 percent) of outside shareholders voted for the dissident slate of candidates.

- As CEO, he wielded significant control over the firm.

The problems that shareholders face with quasi-majority shareholders are a hint of what can happen when an actual majority holder controls a firm. Minority squeeze-outs where the majority owner controls more than 50 percent of the firm can be even worse.

Chaparral Resources7 was a company incorporated in Delaware and traded in the United States that owned oil concessions in Kazakhstan. The government of Kazakhstan wanted to maintain several competing national oil firms to be active rather than having a company from one single nation dominate its oil industry. Because of their geographic location, the oil fields of Kazakhstan were of interest to both Russia and China. China's national oil company, CNPC, and Russia's Lukoil had been battling to acquire PetroKazakhstan, a Canadian oil company with fields in Kazakhstan, in 2005. A Canadian court eventually ruled against Lukoil's argument that it had a preemptive right to acquire one of PetroKazakhstan's subsidiaries. CNPC then purchased the company for $4.2 billion.

In the meantime, a sideshow that made fewer headlines was Lukoil's success to acquire Nelson Resources for $2 billion. Nelson was incorporated in Bermuda and traded in Canada. Lukoil's acquisition price amounted to roughly 15 percent less than the trading price of Nelson on the Toronto Stock Exchange prior to the announcement. Luckily for Nelson's insiders, they had exercised their options and sold shares prior to Lukoil's takeunder proposal.

Ironically, CNPC reciprocated by suing Lukoil over a stake in a joint venture that it had with Nelson, claiming to have preemptive rights to purchase Nelson. In the end, Lukoil succeeded and acquired Nelson. Kazakhstan's government was happy because Lukoil's win at Nelson restored the balance between Russia and China in its oil fields.

For shareholders of Chaparral Resources, however, the Nelson acquisition was the beginning of a nightmare. Nelson owned 60 percent of Chaparral Resources, and now that it was part of Lukoil through its subsidiary Lukoil Overseas Ltd., that firm's management controlled these shares. The successful takeunder of Nelson emboldened Lukoil's management to attempt the same at Chapparal.

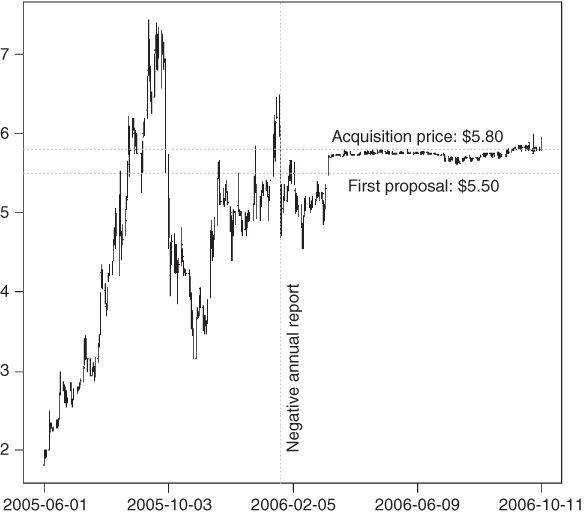

Lukoil began by fudging the 2005 annual report on form 10-K. During its preparations, a Lukoil executive instructed Chaparral's staff to “add something a little negative to the report” and complained that it conveyed a “positive impression” and used “positive words.” Production data that would have shown growth was also removed from the report, to make sure that investors saw nothing positive in the firm. Production had already been falling because the lease for the only drilling rig on its Karakuduk oil field had expired. The lease's expiration was in no way an extraneous event. It had been orchestrated carefully by Lukoil. The rig was leased jointly by Lukoil and Chaparral, and Lukoil simply refused to renew its lease. The rig's owner was urging a prompt renewal, fearing a loss of income, but Lukoil prevailed. Moreover, leases for more rigs had already been lined up and an increase in production was forecast by Chaparral internally, but this information was not communicated to shareholders in the annual report. The gloomy tone of the report and absence of good news had the desired effect: Chapparal's stock dropped by 23 percent (see Figure 11.3).

Figure 11.3 Chapparal Resources

Lukoil's executives regarded the Karakuduk oil field as theirs, even though it was exploited jointly by Lukoil and Chaparral. In an e-mail, the chief financial officer of Chaparral complained about Lukoil's regional director for Kazakhstan, Boris Zilbermints, making “noises” about payments from the oil field's revenue to Chaparral, which “is letting the minority shareholders receive funds.” This was an example of what a Chaparral director described in another e-mail as “the Russian way of doing business.” So were some of the other scare tactics that Lukoil used. It threatened to shut in the Karakuduk field if no deal were reached, or to cease development or fire the board of directors.

The board of directors did create a committee of independent directors to evaluate Lukoil's buyout proposal. At least one of the two directors on the committee, however, appears to have had more concern for Lukoil's interests than for those of the minority shareholders. He leaked the valuation range that Chaparral's financial adviser had calculated to Lukoil, so that Chaparral was negotiating with a buyer that knew the price range of the seller. The two directors appear to have been well aware of the problematic nature of the buyout, as they negotiated a highly unusual clause in their indemnification agreement: If there was a lawsuit in connection with the merger, they would be paid $300 per hour for time spent defending themselves. In other words, the less they represented shareholders, the longer the lawsuits would last, and the more they would be paid.

With the stock price depressed artificially, Lukoil made a lowball offer for the shares of Chaparral's minority shareholders. Lukoil's initial bid of $5.50 per share was soon raised to the final price of $5.80 when it became clear that this was a level at which one institutional holder was willing to sell. While Chaparral and Lukoil were debating whether $5.50 or $5.80 was the right price, Chaparral's financial adviser indicated that the value of the firm in the $8 to $11 range.

Lukoil completed the acquisition for $5.80 per share, but this was not the end of the road for the minority shareholders. The rest of the story is discussed in Chapter 13.

Family Control

Control of publicly traded companies by their founders and their families, often for several generations, is the norm outside of the United States. Frequently, they exercise control while owning less than the majority of the capital. But even within the U.S. governance it is more widespread than one would expect. Governance analysts at the Corporate Library estimate that 170 of the 1,800 firms that it tracks, or almost 10 percent, can be classified as family firms. These are firms where “family ties, most often going back a generation or two to the founder, play a key role in both ownership and board membership.” An additional 163 firms are classified as founder firms, in which the founder owns more than 20 percent of the equity.8 Overall, almost one publicly traded firms in five is under the influence of a founder or family. Even some of the largest companies in the world like Google or Alibaba have structures that allow their founders to exercise effective control at the expense of minority shareholders.

Two principal structures allow founders and their families to exercise control over a company when they own only a minority of the capital:

- Holding companies and interlocks

- Supervoting shares

Holding companies are more common in Europe and Asia as a means of controlling a firm, whereas supervoting shares are the method of choice in the United States. This is partially due to listing rules—some exchanges, such as the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, insist on rigorous implementation of the one share, one vote principle and do not allow companies with multiple share classes to list. As a result, tycoons have found other ways to achieve the same goal. And, of course, it should not be forgotten that in some cases a family or founder does own an outright majority of the shares the traditional way and can exercise control directly.

Control through Holding Companies

The example of Dutch beer brewery Heineken illustrates well how holding company structures can allow a group of holders to control the entire firm despite owning only one quarter of the economic capital. The Heineken family around Charlene de Carvalho-Heineken controls through L'Arche Green NV, at the time of writing, 51.74 percent of Heineken Holding NV, a holding company that owns 50 percent of the outstanding shares of Heineken NV, the actual brewing business. The other half of Heineken NV and the other 48.26 percent of Heineken Holdings NV are held by outside investors, including the strategic investor FEMSA, a Mexican brewing concern. No potential acquirer could purchase Heineken NV without the support of Heineken Holding NV, giving the family effective control with only about one quarter of the economic interest.

That alone would be sufficient to frustrate potential acquirers. However, the relationship between the operating company and the holding goes even deeper. The holding is managed by the executive of the operating company, so that the two entities are very closely intertwined, further complicating attempts to acquire the firm. It is clear that any hostile takeover or even just an activist investor seeking to remove bad decision takers would be frustrated in their approach.

While the structure of Heineken and its holding company is straightforward, in many instances multiple layers of holdings can make it much harder for arbitrageurs to understand how strong someone's control over a firm actually is. In Asia, ownership through multiple vehicles creates a complex web of interlocks that can be very difficult for investors to penetrate. In addition, disclosure rules are often so weak that determining beneficial ownership and control of a public company requires some effort. Hong Kong in particular is well-known for the complexity of some of the holding company structures that patriarchs use to control their empires. For example, Asia's most prominent businessman Li Ka-shing controls 39 percent of Cheung Kong, which, in turn, controls 52.4 percent of Hutchinson Whampoa. While it owns only 46 percent of Hui Xian REIT directly, other Cheung Kong subsidiaries hold additional shares, namely Hui Xian Holdings Ltd. and Cheung Kong China Property Development, giving Li Ka-shing effective control.

Control through complex holding company structures has many disadvantages and shareholders risk receiving well below fair value when the majority owner decides to take the company private. An example that fits this description is Guoco Group, a diversified Southeast Asian conglomerate that originated in Malaysia but now is listed in Hong Kong with property development, banking, leisure, and investment interests in the region. Most notably, it controls 15 percent of Bank of East Asia, itself a perennial takeover candidate and one of the most valuable individual parts of Guoco. 74.5 percent of Guoco Group is held by Hong Leong Co Malaysia, which, in turn, is controlled by the two brothers Quek Leng Chan (49.27 percent) and Kwek Leng Kee (36.04 percent). On December 12, 2012, the two brothers issued a takeover proposal to acquire all remaining shares in Guoco Group for HKD88 per share. Although this represented a nice premium to the pre-announcement trading level of around HKD 70, it was an atypically large 40 percent discount to book value. For years, Guoco had been trading among Hong Kong's holding companies with the largest discount to book value, so it could be argued that the Kwek/Quek brothers were simply incorporating a market discount into their pricing. However, if not at privatization, when else should shareholders be entitled to receive the full value of their shares? Besides, several factors suggest that the lowball bid may have been engineered carefully with the intention of paying as low a price as possible. Guoco had booked large marked-to-market losses in its investment portfolio, so at a minimum the transaction was timed to coincide with a period of bad earnings. Worse, recognition of the losses may have been timed with a view to the intention to launch a takeover offer. Guoco also omitted its interim dividend in March 2013, when it had become increasingly clear that shareholders were unwilling to tender. This was clearly designed to coerce investors to tender. But shares were trading above the proposed HKD88 price, suggesting that shareholders thought the price was inadequate.

On April 24, 2013, Guoco then raised its bid from HKD88 to 100 per share, still a 37 percent discount to the then slightly higher book value of HKD 156 per share. At this time, Hong Leong made a no-increase statement, which would prevent it not only from increasing the price in this offer, but also from making a new offer for another year. The offer comprised two alternatives:

- Under the unconditional offer alternative, shareholders received HKD88 per share plus an additional HKD12 per share should Hong Leong's stake reach the 90 percent threshold at which it can launch a statutory squeeze-out.

- Under the conditional offer alternative, shareholders would have receive HKD100 only if Hong Leong reaches the 90 percent ownership threshold.

In the end, only 2.57 percent of shares were tendered under the unconditional option, and 8.76 under the conditional option. Shareholders were not willing to accept this lowball offer. Indeed, it had a positive impact on the shares, as it set a new ceiling on the discount to NAV should the majority holders seek to squeeze out the minority investors again. Consequently, the shares did not trade down after the offer lapsed.

Share Class Structures

In other instances, companies have a dual share class structure where the founder or family hold A-class shares with more voting rights than those held by public shareholders. Many large U.S. firms under family control fall into that category, but many stock exchanges outside of the United States do not allow companies with dual share class structures to list, making this control technique impractical there. Prominent examples are many publicly traded newspapers, including News Corp. and the New York Times. But even when a 20 percent holder does not have voting control through the ownership of shares with higher voting rights, a 20 percent holding can be the largest single block of shares held. If the remainder of the shares are held widely in small lots, and many of these holders are retail investors who do not exercise their voting rights, then even a stake as small as 20 percent can yield effective control of a firm.

In general, family influence is a double-edged sword. Sometimes control by a family can improve performance because interests of shareholders, management, and the majority holders are aligned. Unfortunately, there are also many counterexamples where family control led to a meltdown. Some spectacular failures occurred in companies led by controlling families, most recently at Adelphia and Refco. The differentiating factor between the few family-controlled firms that perform very well, the majority that underperforms, and the isolated cases of meltdowns is governance. The Corporate Library assembled a list of five red flags that help investors distinguish between good and bad family-controlled firms:9

- Multiple share classes.

Some firms with multiple classes of shares have both classes traded publicly, while others have special family-only classes.

- Special voting rights.

Families sometimes have the right to elect a majority of the board of directors, or a number of directors that represents less than the majority but is still larger than the economic ownership of the family in the firm. Special voting rights are usually coupled with multiple share classes.

- Layered ownership structures.

The Corporate Library warns investors to steer clear from companies owned by multiple nested family trusts.

- Related party transactions.

Methods managers use to milk public companies through related party transactions were discussed in Chapter 9. In family-controlled firms, the art of related party transactions often is perfected even more. The family earns income from its ownership in the firm, employment by the firm, and transactions with the firm. Leases of corporate headquarters or special loan arrangements are examples of such transactions. The principal problem with related party transactions is that the distinction between personal and corporate assets blurs.

- Special takeover defenses or change of control provisions.

Change of control provisions are sometimes even more favorable for families that own and manage a company than for employee managers. Stockholder voting agreements can lock owner-managers in even more effectively than other takeover defenses.

Arbitrageurs looking at acquisition proposals involving family firms must take these factors into account when estimating the probability of failure. If a company is to be acquired by its controlling owners, arbitrageurs often will encounter some of the problems described in the first section of this chapter. If outsiders make a proposal to acquire a family-controlled firm, the dynamics can become difficult to judge. The acquisition of Anheuser-Busch Cos. by InBev SA, which was discussed in Chapter 5, led to a split in the founding Anheuser Busch family. One group of family members around the CEO of the firm, August A. Busch IV, was unwilling to accept InBev's unsolicited initial bid of $60 per share. Another part of the family supported InBev's proposal. InBev sought to benefit from the rift in the family by proposing to elect Adolphus A. Busch IV, the CEO's uncle and great-grandson of Anheuser-Busch's founder, to the board to replace August. The strategy worked in that the family eventually consented to an acquisition at a price that was $5 higher than the initial bid.

Sometime controlling families simply are unwilling to sell to outsiders. Consider, for example, the 2007 proposal by the Cagle family to take poultry producer Cagle's Inc. private (see Exhibit 11.2). Cagle's was listed on the American Stock Exchange.

The family stated unambiguously that it was “not interested in selling our shares pursuant to an alternative transaction and will only consider a transaction in which we purchase all of the outstanding shares.” The family eventually withdrew its acquisition proposal. With the benefit of hindsight, a sale of the company to a strategic buyer who could have given the business more scale and synergies would have been the best option. Cagle's filed for bankruptcy on October 19, 2011. All of its assets were eventually auctioned off to Koch Foods Inc.