Chapter 5

Sources of Risk and Return

The two most important drivers of returns on merger arbitrage are the deal spread and timing of the closing. Both are discussed briefly in Chapter 2 but are be examined more systematically here. For dividend-paying stocks, dividends are also an important element of return and can, in some instances, even be the only return, as in the case of a preferred stock. Additional ways that arbitrageurs can generate returns are interest on the proceeds of short sales and leverage.

Deal Spread

In Chapters 2 and 4, we discussed how to calculate the spread and factor the risk of a collapse into the equation. In a way, the spread calculation is a chicken-and-egg type of situation: The spread exists because there remains risk, and the risk is explained by the existence of a spread.

Some terminology related to spreads has already been introduced in the discussion of Chapter 2. We will clarify some of the terms here.

Spreads can be wide or tight and can become more so if they widen or tighten. “Narrow” is less commonly used to describe tight spreads.

Gross spreads exclude dividends, whereas net spreads are supposed to include dividends and all other costs.

Merger arbitrage spreads are typically very tight in absolute terms. A merger arbitrageur rarely makes large returns. However, the seemingly low returns must be viewed against the short time frame in which the returns can be achieved. Typical merger arbitrage spreads are in the range 2 to 4 percent for transactions with little risk of completion. Uninitiated observers may consider merger arbitrage unattractive because of the apparently low returns that can be achieved by the strategy. A return is meaningful only in the context of the time period over which it can be achieved. For merger arbitrage, returns typically are achieved in a very short time frame of three to six months. As we will discuss later in this chapter, the average time frame for the closing of a merger is 128 days, or four to five months. On the back of an envelope, returns of 2 to 4 percent achieved over four months amount to 6 to 12 percent on an annualized basis. This compares favorably to a long-term return on the stock market of 10.7 percent.1 A better comparison of general equity and merger arbitrage returns will take the riskiness of this return into account, as we did in Chapter 3.

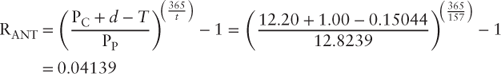

A spread is expected to narrow over time and finish at zero at the closing of the merger, as we saw in the idealized diagram in Figure 2.2. Naturally, this does not happen in a straight line. The evolution over time of an actual spread, that of Hewlett-Packard's acquisition of Autonomy Corporation, is shown in Figure 5.1. The spread fluctuates, albeit less so then the equity market in general, as we discussed in Chapter 3. For now, it is sufficient to say that the principal driver in fluctuations in the deal spread have to do with events that are specific to the completion risk of the transaction. A secondary driver depends on general trading activity. Many shareholders want to exit their investment once a firm has announced that it is going to be acquired, because there is little upside left and they are unwilling to assume the completion risk. A large sell order, or several smaller orders that happen to arrive at the same time, can lead to a temporary widening of the spread even though no fundamental news has arrived. In those situations, arbitrageurs are faced with the difficult decision of whether to take advantage of the temporarily widened spread and increase their holdings or to join the selling. After all, it is possible that some real information pertaining to an increased risk of deal failure has leaked into the market.

Figure 5.1 Evolution of the Spread of the Autonomy Merger

The level of interest rates is by far the most significant determinant of the overall level of merger arbitrage spreads. If interest rates are high, merger arbitrage spreads must be wide to provide an attractive investment alternative to other short-term investments. When interest rates are low, capital will be allocated to merger arbitrage, driving down returns available to arbitrageurs.

Other factors influencing deal spreads are, among others:

- Overall deal volume. If more arbitrage opportunities exist, spreads will be wider as arbitrage capital will be deployed over a larger deal universe. However, as discussed in Chapter 3, this is not the strongest driver of spreads.

- Short rebate. The short rebate, discussed later in this chapter, is a big contributor to returns for merger arbitrageurs.

- Cash mergers versus stock-for-stock mergers. Spreads tend to be wider for cash mergers due to the higher risk that financing may not be available at the anticipated closing. A pure stock-for-stock merger does not have financing risk and will have a smaller spread. However, stock-for-stock mergers provide extra income through the short rebate, which is not available to pure cash mergers.

Two Aspects of Liquidity

Liquidity is a term that describes the ease with which a trader can enter and exit positions in a stock. A liquid stock is one that can be traded easily without any impact on the stock price. Trading volume and bid/offer spreads are the two principal characteristics of liquidity. A high volume and tight bid/offer spreads usually go hand in hand.

Liquidity drives merger arbitrage returns in two ways:

- Merger arbitrageurs provide liquidity to sellers.

- Arbitrageurs can earn a liquidity premium on illiquid stocks.

Most mergers are done at a significant premium to the last trading price of the stock. Following the announcement, the stock jumps to a level that is very close to the eventual buyout value. At this point, many long-term holders will try to sell in order to capture most of the acquisition premium. They probably acquired the stock as a value or growth investment, and now that their investment thesis has played out successfully, they have no more interest in holding the stock. Their business is not assuming the completion risk of the merger, but it was the original value or growth strategy. Therefore, they will try to sell.

So who is buying? Other long-term investors will have no interest in a stock that provides limited upside, much downside in the event that the deal collapses, and will be taken off the market shortly. Arbitrageurs are the only buyers of such stocks. The liquidity they provide to the sellers allows them to move on to their next investment. If there were no arbitrage buying, the market would face an overhang of sell orders, and the stock would trade at a wide spread to its buyout price. By providing liquidity under unusual circumstances such as a merger, merger arbitrage contributes to the efficiency of the stock market. In economic terms, it is the provisioning of the liquidity to the market that generates returns for merger arbitrageurs. And because liquidity is limited with an overhang of sell orders after a merger announcement, those who provide liquidity should earn a premium return. Arbitrageurs are liquidity providers; those who sell are liquidity takers.

Trading volumes always spike on the first trading day following the announcement of a merger. The Autonomy example illustrates this point well. Figure 5.2 shows the stock price and volume for the common stock of Autonomy. On the day of the buyout announcement, when Autonomy's stock jumps over £10 to close at £24.52, volume spiked and over 48 million shares were traded. On each of the following two days, volumes were above 10 million but soon dropped to a few million shares per day. Most days saw volumes in the low single-digit millions. This compares to trading volumes of 600,000 to one million shares on most days in the weeks preceding the merger announcement. The only way that the high volume of sales orders can be absorbed in a stock that has little interest as a going concern is because arbitrageurs provide sufficient liquidity through their buy orders. In the absence of arbitrage, long-term investors eager to sell would receive substantially lower prices.

Figure 5.2 Price (left scale; line) and Volume (right scale, in thousands; bars) Chart of Autonomy Common Stock

Another form of liquidity that can help arbitrageurs, or any investor for that matter, earn additional return is the trading volume of the stocks involved in the merger. Liquidity describes the trading volume of a stock and the ability of an arbitrageur to take a position. An arbitrageur will find it difficult to establish a position in a stock with a low trading volume. Typically, these are companies with a small market capitalization, or companies where only a small fraction of the outstanding stock is held by the public and large blocks are controlled by long-term investors who do not buy or sell. This liquidity is somewhat related to the liquidity just discussed, because the overhang of sell orders can have a larger impact on spreads for stocks that do not trade large volumes than for large blue chips.

Low levels of liquidity prevent many large arbitrageurs from taking positions in smaller mergers, even if the annualized return appears attractive. Low trading volumes can make it difficult to build up holdings of even just a few million dollars. For an arbitrageur with an investment book in the billion-dollar range, it is not worth the effort to analyze such a small merger. As a result, spreads can remain attractive for a long period of time for those arbitrageurs small and humble enough to get involved in the transaction.

This is another manifestation of the small-cap premium that has been observed in the investment literature. Small caps delivered returns 4 percent larger than large-cap stocks over the 50 years through 1981, but the small-cap premium has been more difficult to observe since then. Merger arbitrage may be the one area where it managed to survive until today.

Low liquidity can also affect mergers of large companies that have an illiquid class of securities outstanding in addition to a liquid one. One opportunity that I have encountered frequently in large mergers is preferred stock issued by companies that have a liquid common stock. The preferred stock is typically a supplemental element in the firm's capital structure and has a much smaller capitalization than the common stock. As a result, its liquidity is much lower. The spread of the preferred stock is therefore much wider than that of the common stock. Preferred stocks are often liquidated in a merger. However, there is one caveat with preferred shares that arbitrageurs must be mindful of: Before trying to arbitrage a preferred stock, an arbitrageur must make sure that the preferred stock actually will be liquidated in the merger. In many instances preferred stock remains outstanding after a merger. An example of a merger in which only the common stock was acquired but several classes of preferred stock remained outstanding is the acquisition of Duquesne Light Company by Macquarie Infrastructure Partners and The DUET Group that closed at the end of May 2007. After the merger, six series of preferred stock remain outstanding:

| Duquesne Light Co.: | $2.10 Series Cumulative Preferred Stock |

| 3.75% Series Cumulative Preferred Stock | |

| 4.10% Series Cumulative Preferred Stock | |

| 4.15% Series Cumulative Preferred Stock | |

| 4.20% Series Cumulative Preferred Stock | |

| 6.50% Cumulative Preferred Stock |

All of these preferred shares continue to trade for several years, albeit with little liquidity in the over-the-counter market. On many trading days, not a single transaction takes place in these stocks. These securities were redeemed on November 17, 2014.

Companies take this as an opportunity to buy back outstanding preferred stock at a discount. When Brookfield Office Properties acquired MPG Office Trust in the fall of 2013, it made a tender offer for the preferred stock at the $25 notional amount, even though this was a cumulative preferred on which $8.90 in dividends had accrued. Brookfield speculated that investors would simply tender at the notional amount and forgo the dividends that had accrued for several years at a rate of 7.625 percent. However, only 3.8 percent of the holders of the preferred tendered their shares and were paid out. After the closing of the merger, the preferred was converted into preferred shares of Brookfield DTLA Fund Office Trust Investor Inc. under substantially similar terms. Investors were expecting to receive accumulated dividends as Brookfield cannot extract equity gains from the subsidiary that issued the preferred.

The scenario that arbitrageurs are more interested in is when a preferred stock is liquidated in a merger. Trustreet Properties, a restaurant real estate investment trust that was acquired by General Electric on February 27, 2007, had a Convertible Preferred stock traded on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) with much smaller trading volume than its common stock. Trading volume of the preferred stock is much more erratic than that of the common stock. The volume chart is shown in Figure 5.3. Before the announcement of the merger, only a few thousand shares changed hands every day, and the occasional day with large trades of 20,000 or more shares is easily identifiable. Following the announcement of the merger, trading volume remains low on most days, amounting to only a few thousand shares. However, large trades generate much more volume now with spikes of up to 100,000 shares. At a price of $25 per share, that amounts to a mere $2.5 million of trading volume. For days on which only a few thousand shares traded, the dollar value is of the order of magnitude of only $100,000. By comparison, Trustreet's common stock traded volumes north of 400,000 shares with a value of around $17 per share, or a total trading volume of $6.4 million on most days. Clearly, it is difficult for a large arbitrageur to establish a meaningful position in Trustreet's preferred stock, and as a result, the common stock had a tighter spread than the preferred.

Figure 5.3 Volume Chart of Trustreet Series C Preferred Stock

As discussed previously, trading volume and bid/offer spreads are closely related. Stocks with low trading volumes have wider bid/offer spreads than those with good liquidity. Bid/offer spread, also known as bid/ask spread, sometimes can be one of the sources of returns. Stocks are quoted with two prices: a bid price at which a buyer in the market is willing to acquire a stock, and an ask (offer) price at which someone is willing to sell. These quotes are placed either by other investors or market makers. In the case of electronic communication networks (ECNs), the quotes come from other investors. In organized exchanges or Nasdaq, the quotes are placed by market makers or specialists, who manage an inventory of stocks and provide buyers and sellers with liquidity.

Bid/offer spreads are related to liquidity. Stocks with low trading volumes tend to have tighter bid/offer spreads. Figure 5.4 shows the screenshot of market quotes for MCG Capital, a company with a market capitalization of only $164 million, five minutes before the New York market close. MCG Capital was going through an acquisition by a private company run by PennantPark Floating Rate Capital Ltd, while also subject to a hostile bid by Philip Falcone's HC2 Holdings. The order book provides information on different trading venues and market makers and their posted bid and offer prices and volumes. For example, it can be seen that Knight Trading, whose abbreviation is NITE, posts a bid of $4.49 for 100 shares, whereas UBS, whose abbreviation is UBSS, posts an offer of 3,600 shares at $4.53. The lack of liquidity is evidenced by the low trading volume of only a quarter million dollars that day. It is difficult for an arbitrageur managing several hundred million dollars in assets to build a position in this stock that is substantial enough to have an impact on the portfolio. In can be seen from the figure that the visible part of the order book amounts to only 17,700 shares on the bid side and 9,900 on the offer. An order to buy 10,000 shares, or less than $50,000 worth of stock, at the market would lift the entire order book from $4.52 all the way to $4.65.

Figure 5.4 Order Book for MCG Capital

Smaller stocks will have even less liquidity. It is not uncommon to see trading volumes below $100,000 per day in micro-cap stocks. Such securities will also have a wide bid/offer spread. In the example at hand, the bid/offer spread is only one cent, but in even more illiquid securities it can amount to several cents. An arbitrageur must place buy and sell orders in such an illiquid security carefully. After all, arbitrage spreads are very narrow to begin with. If an arbitrageur pays several cents in bid/offer spread, then much of the arbitrage spread is forgone. Conversely, the arbitrage spread can be improved if limit orders are placed carefully between the bid and ask. The drawback of that strategy is that the limit orders may not be filled.

For comparison, order book of highly liquid Mylan NV is shown in Figure 5.5. Mylan had a market capitalization of $33 billion and, like MCG, was subject to a hostile bid by Teva for $82 per share at the time. The daily trading volume through the same time of day was $250 million, or by a factor of 1,000 higher than that of MCG Capital. With so much trading, it is easy for an arbitrageur to build a position worth many millions of dollars in this stock.

Figure 5.5 Order Book for Mylan NV

Unfortunately, with improvements in technology, posted bid/offer prices are becoming less and less relevant. Many market participants use computerized trading systems that show only a small fraction of the true volume that they are willing to buy or sell. An algorithm breaks large orders into many small partial orders that are then routed based on the parameters fed into the algorithm. Once a fraction of an order is executed, the trading software automatically places another order. These systems allow for better execution of larger orders. If a large order were shown in its entirety, other investors would realize that they stand a small chance of getting executed at this price and will drive the price up (buy order) or down (sell order). By placing the large order tactically in smaller pieces, an investor can improve her execution quality. In addition, “dark” pools of liquidity are available to participants of certain ECNs. These are orders that are not shown at all in the market but are matched if an order is placed with the same ECN. This has led to a paradox. Although technology has made stock price information much more available and easier to process, it has also made the information that can be seen much less relevant. If posted order books represent only a fraction of actual order books, it is much more difficult for market participants to gauge the state of the market.

Liquidity also has an impact on a less obvious aspect of merger arbitrage: short selling. The ability to borrow a stock to sell short is linked to its liquidity and free float. More on short selling follows later in this chapter.

Finally, liquidity also determines indirectly the outcome of mergers. The more liquid a stock, and the easier it is for arbitrageurs to build positions, the greater the proportion of stock held by arbitrageurs when the merger is voted on. This effect is discussed in the next section.

Beneficial Participation of Arbitrageurs

Because arbitrageurs have a strong interest in seeing the merger close, they will vote in favor. Following the announcement of a merger the shareholder base undergoes a major shift. As already mentioned, long-term holders sell to arbitrageurs whose interest is to earn the spread from a successfully completed merger. In addition to being liquidity providers their purchase of shares increases the likelihood of a merger closing. Therefore, mergers sometimes are structured to appeal to arbitrageurs. Table 5.1 shows arbitrageurs' holdings as a percentage of outstanding shares for a number of large mergers since 1985. The importance of arbitrageurs has increased over time. While through 1996 arbitrageurs rarely held more than 30 percent of a stock, their holdings are sometimes around 50 percent for more recent mergers. Companies that want to improve the chances of closing their mergers should structure them in a way that they appeal to arbitrageurs.

Table 5.1 Arbitrageurs' Holdings of Target Company Stock in Selected Mergers

| Year | Announcement Date | Bidder Name | Target Name | Target Market Value ($000s) | Arbitrageurs' Holding (%) | Deal Outcome |

| 1985 | 4/8/1985 | Investor Group | Unocal Corp. | 15,172,254 | 16.96 | Withdrawn |

| 1986 | 10/20/1986 | Tri-Star Pictures Inc. | Loews Theaters Corp. | 9,130,790 | — | Completed |

| 1987 | 3/26/1987 | BP America | Standard Oil Co. | 27,853,840 | 16.85 | Completed |

| 1988 | 10/20/1988 | Investor Group | RJR Nabisco Inc. | 27,795,615 | 21.63 | Withdrawn |

| 1989 | 7/27/1989 | Bristol-Myers Co. | Squibb Corp. | 16,641,443 | 31.56 | Completed |

| 1990 | 7/12/1990 | GTE Corp. | Contel Corp. | 8,021,125 | 31.65 | Completed |

| 1991 | 8/12/1991 | BankAmerica Corp. | Security Pacific | 5,555,271 | 25.10 | Completed |

| 1992 | 5/27/1992 | Sprint Corp. | Contel Corp. | 4,861,927 | 27.11 | Completed |

| 1993 | 10/13/1993 | Bell Atlantic Corp. | Tele-Communications Inc. | 15,720,005 | 36.89 | Withdrawn |

| 1994 | 11/10/1994 | Shareholders | Allstate Corp. | 13,835,660 | 9.24 | Completed |

| 1995 | 7/31/1995 | Walt Disney Co. | Capital Cities/ABC Inc. | 22,179,509 | 28.29 | Completed |

| 1996 | 4/22/1996 | Bell Atlantic Corp. | NYNEX Corp. | 26,143,261 | 29.16 | Completed |

| 1997 | 10/1/1997 | WorldCom Inc. | MCI Communications Corp. | 23,294,576 | 47.07 | Completed |

| 1998 | 4/6/1998 | Travelers Group Inc. | Citicorp | 94,508,038 | 45.36 | Completed |

| 1999 | 1/18/1999 | Vodafone Group PLC | AirTouch Communications Inc. | 60,079,773 | 36.76 | Completed |

| 2000 | 1/10/2000 | America Online Inc. | Time Warner | 116,513,913 | 50.72 | Completed |

| 2001 | 3/12/2001 | Prudential PLC | American General Corp. | 20,812,206 | 42.60 | Withdrawn |

| 2002 | 7/15/2002 | Pfizer Inc. | Pharmacia Corp. | 53,294,077 | 46.87 | Completed |

| 2003 | 10/27/2003 | Bank of America Corp. | FleetBoston Financial Corp | 42,347,745 | 37.85 | Completed |

| 2004 | 2/11/2004 | Comcast Corp. | Walt Disney Co. | 56,476,998 | 40.79 | Withdrawn |

Source: Micah S. Officer, “Are Performance-Based Arbitrage Effects Detectable? Evidence from Merger Arbitrage,” Journal of Corporate Finance 15, no. 5 (2007), 793–812. Reprinted with permission by Elsevier.

A more systematic analysis of mergers between 1994 and 2008 supports the increasing role played by arbitrageurs. Charles Cao, Bradley A. Goldie, Bing Liang, Lubomir Petrasek2 find that in the 1990s arbitrageurs holdings of target companies exceeded 5 percent in less than one mergers in 10. Between 2006 and 2008 in almost two thirds of all mergers arbitrageurs ended up holding at least 5 percent of the shares. The numbers in this study most likely understate the role played by arbitrageurs in mergers as their holdings can only be estimated from publicly available information, and many arbitrageurs may not cross reporting thresholds or invest through instruments that were not reportable at the time of the study.

This study and numerous other studies support the contention that arbitrageur participation increases the likelihood of successful deal completion. Jim Hsieh and Ralph Walkling3 find that arbitrageurs not only hold a larger portion of shares in transactions that are ultimately successful, but also that their involvement correlates with the probability of bid success, bid premia, and arbitrage returns. This suggests that the mere presence of arbitrageurs in the market encourages bidders to pay higher prices, or conversely, that when prices are too low arbitrageurs have enough clout to force bidders to pay full value.

Timing and Speed of Closing

After the deal spread, the second crucial aspect to the profitability is the time a merger takes to complete. A small spread earned in a short period of time can yield a higher annualized return than a large spread in a merger that drags on for a several years. Arbitrageurs will pay particular attention to the question of timing.

Mergers can be structured in two different ways: as classic mergers, which require a vote by shareholders and in most countries court approval, or as tender offers, which do not require a vote and where shareholders simply sell their shares to the buyer through a tender process. The difference between these mechanisms is described in more detail in Chapter 6.

As a general rule, tender offers can be completed much faster than mergers, because there is no need to hold a shareholder meeting with the associated advance notice requirements, or follow the calendar of a court. Tender offers can close in as little as 30 to 60 days. In a tender offer, shareholders can decide whether to tender their shares directly to the acquirer. The buyer will try to obtain all shares, but in practice, some shareholders will not tender their shares. Shareholders are not necessarily opposed to the merger but may simply fail to tender for a variety of other reasons. To allow the buyer to acquire the entire target despite not obtaining 100 percent of the shares in the tender offer, tender offers are structured in two steps:

- A tender offer is launched.

- A short-form merger is completed to squeeze out any remaining shareholders.

Under the laws of most jurisdictions, once a shareholder reaches a certain threshold of ownership, usually 90 or 95 percent, it can force the minority shareholders to sell it their shares. This provision is called a squeeze-out of minority shareholders. The threshold depends on the applicable law. It is over 90 percent in most U.S. states but can be as low as 85 percent. In Delaware, the threshold is 90 percent, while most European countries require 95 percent. Following a tender offer, the buyer will take advantage of a squeeze-out to obtain control of the target from the last few remaining shareholders.

In the United States a top-up option is available to a buyer who cannot get to the 90 percent squeeze-out threshold to increase its holdings by acquiring newly issued shares of the target.

It is a frequent occurrence that buyers do not get to the requisite 90 percent threshold at the expiration of the first tender offer period. Multiple extensions of tender offer periods are not unusual. In some instances, shareholders do not tender out of ignorance or for other reasons that can be difficult to pinpoint. In those scenarios, tender offer extensions typically work.

The situation is different when shareholders refuse to tender because they believe that the price is insufficient. In these cases, a new sweetened tender offer with a higher price is necessary. Several variations of this scenario can be distinguished. Lafarge S.A. wanted to acquire the publicly held 46.8 percent of its NYSE-traded subsidiary Lafarge North America (see Figure 5.6). Lafarge S.A. first offered $75 per share price on February 6, 2006, for Lafarge North America, a proposal that few shares were tendered into. Shares of Lafarge North America traded well above $75, indicating that the market expected a substantial price improvement. A subsequent $82 tender offer on April 4 received a similarly lukewarm reception. Only following the third sweetened offer of $85.50 per share were sufficient shares tendered to bring Lafarge above the 90 percent threshold: At the expiration of the offer on May 15, it held 92.37 percent of Lafarge North America and was able to squeeze out the minority shareholders.

Figure 5.6 Lafarge North America

In another variation of this strategy, arbitrageurs acquire a large enough stake in the target company so that the minimum voting or tender offer requirements cannot be met. In this case, the acquirer will boost the acquisition price in order to get a sufficiently large number of shareholders to support the transaction. During fall of 2013, German drug wholesaler Celesio AG agreed to sell itself to McKeeson Corp with a minimum tender condition of 75 percent. Shortly after the announcement, Elliott Associates became a shareholder in Celesio AG and reported owning close to 25 percent. Elliott announced publicly that it considered the €23 acquisition price inadequate. Based on trading activity in the stock market, participants could estimate that Elliott must have had acquired a good portion of its holdings above the €23 tender offer price and hence was likely to be serious about not accepting the proposed price. This observation likely caused other market participants to not tender their stakes and hold out for a higher price. Although Celesio's majority shareholder, holding company Franz Haniel & Cie, was committed to tendering its 50.01 percent stake, the acceptance condition was not met.

McKeeson eventually raised its takeover offer to €23.50 per share. However, this was insufficient to sway enough shareholders to tender. Even though Elliott and Haniel both agreed to support the revised, higher transaction, the company still failed to gain the required 75 percent participation. The most likely cause for the failure was the short period of time between the increase in the merger consideration and the closing of the transaction. Even shareholders who wanted to participate may not have had the time to tender. After the merger thus failed, Elliott purchased more shares in the open market and eventually McKeeson came to a private agreement to purchase 75 percent of the shares from Haniel and Elliott. Minority shareholders were not able to participate; however, as McKeeson was likely to sign a domination and profit sharing agreement with Celesio subsequently, which leads to compensation payments to minority shareholders based on the firms appraised value, the shares of Celesio surged to over €25.

Mergers differ from tender offers because they require shareholder approval. The notice periods prior to the annual meeting can be longer than the entire process for a tender offer. The pros and cons of acquiring a company through a merger or tender offer are discussed in Chapter 6. For now, suffice it to say that mergers are more complex and tend to be drawn out for a longer period of time.

The statistics of time periods required to complete an acquisition reflect this. Table 5.2 shows the average and maximum time periods required to close a merger for a range of U.S. industries. Overall, mergers close on average in a little more than four months. Companies in the energy and power industry along with financials take the longest to complete their mergers. This finding reflects the high level of regulation of these sectors and the multiple state regulatory bodies that must give their consent before the closing. Smaller mergers with a value below $500 million close half a month faster than those with a value in excess of that level.

Table 5.2 Time Periods Required to Close a Merger in the United States, by Industry

| $50–500 Million | >$500 Million | All | |||

| Average | Maximum | Average | Maximum | Average | |

| Commercial Services | 93.6 | 295 | 108.4 | 359 | 106.1 |

| Communications | 128.0 | 308 | 176.8 | 374 | 152.5 |

| Consumer Durables | 106.9 | 313 | 133.2 | 257 | 106.9 |

| Consumer Non-Durables | 104.7 | 344 | 132.5 | 330 | 119.6 |

| Consumer Services | 117.9 | 398 | 181.2 | 622 | 156.0 |

| Distribution Services | 93.9 | 217 | 117.5 | 290 | 118.2 |

| Electronic Technology | 95.4 | 384 | 113.8 | 309 | 100.6 |

| Energy Minerals | 138.4 | 401 | 130.1 | 358 | 138.8 |

| Finance | 154.4 | 688 | 146.0 | 764 | 156.3 |

| Health Services | 109.0 | 358 | 150.2 | 430 | 140.1 |

| Health Technology | 84.6 | 357 | 105.1 | 359 | 98.1 |

| Industrial Services | 115.6 | 365 | 149.7 | 365 | 119.6 |

| Miscellaneous | 123.0 | 129 | 161.8 | ||

| Non-Energy Minerals | 118.6 | 232 | 138.0 | 447 | 143.2 |

| Process Industries | 98.1 | 235 | 150.3 | 487 | 128.4 |

| Producer Manufacturing | 94.6 | 315 | 131.4 | 513 | 114.4 |

| Retail Trade | 106.3 | 365 | 117.2 | 273 | 110.8 |

| Technology Services | 88.9 | 358 | 102.7 | 581 | 93.7 |

| Transportation | 112.3 | 220 | 129.9 | 252 | 124.5 |

| Utilities | 190.9 | 467 | 338.9 | 546 | 254.9 |

| Total | 117.3 | 688 | 135.9 | 764 | 128.2 |

Source: Author's calculations based on Mergerstat data.

Interestingly, mergers that fail to close do so a little faster on average than those that close successfully, as shown in Table 5.3. It would have been more intuitive if mergers that fail take longer until it becomes clear that the merger is beyond hope. This appears to be the case in some individual mergers. Several industries show outliers of mergers that drag on for an extremely long time until they fail. For example, a merger in the financial industry took 687 days until it fell apart for good (the 2004–2006 acquisition of Security Capital by MTN Capital). For most mergers, however, the opposite effect is at work. If a merger runs into obstacles, the parties involved make multiple attempts to rescue the transaction, and eventually succeed. As a result, successful mergers take longer on average.

Table 5.3 Time until the Collapse of U.S. Mergers, by Industry

| $50–500 Million | >$500 Million | All | |||

| Average | Maximum | Average | Maximum | Average | |

| Commercial Services | 99.3 | 265 | 93.7 | 197 | 109.4 |

| Communications | 103.0 | 289 | 99.2 | 217 | 93.3 |

| Consumer Durables | 113.1 | 405 | 98.0 | 203 | 102.9 |

| Consumer Non-Durables | 105.4 | 294 | 96.4 | 213 | 89.0 |

| Consumer Services | 123.5 | 350 | 163.0 | 523 | 126.7 |

| Distribution Services | 56.6 | 168 | 108.0 | 168 | 84.1 |

| Electronic Technology | 122.9 | 398 | 85.8 | 287 | 111.5 |

| Energy Minerals | 125.4 | 295 | 84.7 | 249 | 124.7 |

| Finance | 139.9 | 687 | 140.3 | 413 | 143.2 |

| Health Services | 172.7 | 372 | 68.4 | 151 | 121.7 |

| Health Technology | 100.9 | 302 | 122.1 | 406 | 118.6 |

| Industrial Services | 155.5 | 221 | 117.3 | 176 | 118.4 |

| Miscellaneous | 90.0 | 117 | 128.7 | ||

| Non-Energy Minerals | 83.7 | 193 | 156.3 | 336 | 96.4 |

| Process Industries | 145.9 | 346 | 227.8 | 530 | 172.0 |

| Producer Manufacturing | 92.5 | 183 | 160.3 | 345 | 148.7 |

| Retail Trade | 102.3 | 283 | 138.5 | 287 | 114.2 |

| Technology Services | 66.5 | 221 | 120.9 | 337 | 98.9 |

| Transportation | 109.7 | 247 | 132.2 | 429 | 104.5 |

| Utilities | 38.0 | 43 | 220.7 | 633 | 186.8 |

| Total Result | 111.5 | 687 | 133.9 | 633 | 119.9 |

Source: Author's calculations based on Mergerstat data.

Smaller mergers both fail and close faster than larger ones. This finding reflects the complexity of large mergers that are more likely to require antitrust approvals and thus take longer, whether they succeed ultimately or not.

For both collapsed and successful mergers, a few outliers lie at a multiple of the average. These rare events skew the average values to the upside. It should also be remembered that these tables show averages of mergers and tender offers. Tender offers, however, take much less time to close than mergers. Therefore, the distribution of closing times underlying both tables is binomial rather than bell shaped.

In most jurisdiction outside of the United States, mergers close faster than in the United States (Table 5.4). This is partly the result of the tighter requirements of the Takeover Code on the timeline of a transaction, which has been emulated in many countries outside of the United Kindgom, as will be discussed later. In contrast, there are no corresponding constraints on the timeline of U.S. mergers. Moreover, the plethora of regulatory agencies that have proliferated much more in the U.S. federalist system than in other countries contributes to extending the time needed to close U.S. transactions. Continental Europe is an exception. Not only has it a much smaller deal volume than the United States, but the few mergers that do occur take significantly longer to close or fail. The difference is particularly pronounced relative to the United Kingdom, whose Takeover Code is seen as a model for continental European merger legislation.

Table 5.4 (a) Timing of Public Company Mergers in Canada

| Completed Mergers | Canceled Mergers | |||

| Sector | Average | Longest | Average | Longest |

| Commercial Services | 76.6 | 135 | 140.0 | 140 |

| Communications | 152.8 | 260 | 354.0 | 530 |

| Consumer Durables | 65.6 | 103 | ||

| Consumer Non-Durables | 94.7 | 202 | 73.0 | 73 |

| Consumer Services | 128.2 | 476 | 102.3 | 219 |

| Distribution Services | 138.5 | 272 | 46.8 | 114 |

| Electronic Technology | 80.5 | 117 | 79.0 | 128 |

| Energy Minerals | 72.0 | 217 | 88.5 | 347 |

| Finance | 102.9 | 488 | 57.2 | 140 |

| Health Services | 98.0 | 119 | ||

| Health Technology | 77.6 | 154 | 274.7 | 722 |

| Industrial Services | 72.5 | 174 | 128.3 | 199 |

| Miscellaneous | 78.9 | 182 | 65.0 | 121 |

| Non-Energy Minerals | 105.3 | 485 | 83.6 | 290 |

| Process Industries | 139.2 | 266 | 73.5 | 89 |

| Producer Manufacturing | 93.9 | 259 | 133.5 | 228 |

| Retail Trade | 82.1 | 137 | 7.0 | 7 |

| Technology Services | 70.1 | 134 | 70.0 | 70 |

| Transportation | 114.1 | 233 | ||

| Utilities | 93.6 | 179 | 47.5 | 80 |

| Total | 92.2 | 488 | 93.0 | 722 |

Source: Author's calculations based on Mergerstat data.

Table 5.4 (b) Timing of Public Company Mergers in the United Kingdom

| Completed Mergers | Canceled Mergers | |||

| Sector | Average | Longest | Average | Longest |

| Commercial Services | 96.6 | 471 | 61.6 | 132 |

| Communications | 100.2 | 193 | ||

| Consumer Durables | 60.3 | 106 | 39.6 | 65 |

| Consumer Non-Durables | 91.5 | 224 | 76.3 | 120 |

| Consumer Services | 87.6 | 495 | 84.6 | 393 |

| Distribution Services | 87.3 | 200 | ||

| Electronic Technology | 77.5 | 167 | 59.3 | 103 |

| Energy Minerals | 99.9 | 291 | 58.8 | 155 |

| Finance | 82.0 | 254 | 59.1 | 221 |

| Health Services | 64.7 | 104 | 23.0 | 23 |

| Health Technology | 106.2 | 345 | 59.0 | 94 |

| Industrial Services | 81.5 | 143 | 52.8 | 127 |

| Miscellaneous | 83.0 | 83 | 303.0 | 303 |

| Non-Energy Minerals | 131.4 | 365 | 117.4 | 384 |

| Process Industries | 103.7 | 224 | 92.0 | 92 |

| Producer Manufacturing | 91.7 | 201 | 78.0 | 218 |

| Retail Trade | 114.4 | 424 | 79.8 | 165 |

| Technology Services | 68.6 | 160 | 96.4 | 353 |

| Transportation | 98.6 | 246 | 60.5 | 90 |

| Utilities | 137.5 | 448 | 100.7 | 294 |

| Total Result | 91.5 | 495 | 71.9 | 393 |

Source: Author's calculations based on Mergerstat data.

| Completed Mergers | Canceled Mergers | |||

| Average | Longest | Average | Longest | |

| Commercial Services | 115.0 | 254 | 131.5 | 192 |

| Communications | 101.3 | 140 | ||

| Consumer Durables | 78.0 | 78 | 36.0 | 36 |

| Consumer Non-Durables | 119.0 | 182 | 82.5 | 165 |

| Consumer Services | 152.4 | 267 | 89.0 | 199 |

| Distribution Services | 134.5 | 273 | 152.0 | 402 |

| Electronic Technology | 68.5 | 94 | 334.0 | 334 |

| Energy Minerals | 126.4 | 356 | 117.9 | 467 |

| Finance | 117.4 | 358 | 102.0 | 280 |

| Health Services | 63.4 | 105 | 47.7 | 130 |

| Health Technology | 113.6 | 140 | 81.3 | 205 |

| Industrial Services | 82.8 | 144 | 98.3 | 132 |

| Miscellaneous | 130.8 | 182 | 73.0 | 151 |

| Non-Energy Minerals | 129.7 | 420 | 117.2 | 630 |

| Process Industries | 108.3 | 138 | 102.2 | 257 |

| Producer Manufacturing | 135.6 | 206 | 47.5 | 63 |

| Retail Trade | 195.5 | 339 | 53.0 | 90 |

| Technology Services | 119.1 | 151 | 126.5 | 170 |

| Transportation | 189.5 | 276 | 123.0 | 142 |

| Utilities | 100.0 | 129 | 94.0 | 94 |

| Total Result | 124.1 | 420 | 105.0 | 630 |

Source: Author's calculations based on Mergerstat data.

Table 5.4 (d) Timing of Public Company Mergers in France, Austria, and Germany

| Completed Mergers | Canceled Mergers | |||

| Average | Longest | Average | Longest | |

| Commercial Services | 290.0 | 290 | 36.0 | 36 |

| Communications | 150.2 | 314 | 91.0 | 91 |

| Consumer Durables | 210.5 | 236 | 51.0 | 51 |

| Consumer Non-Durables | 90.4 | 215 | 108.0 | 140 |

| Consumer Services | 91.8 | 201 | 102.3 | 180 |

| Distribution Services | 61.0 | 61 | ||

| Electronic Technology | 270.5 | 629 | 64.0 | 126 |

| Energy Minerals | 111.0 | 111 | ||

| Finance | 115.3 | 511 | 139.3 | 314 |

| Health Services | 130.0 | 130 | ||

| Health Technology | 160.1 | 217 | 50.5 | 90 |

| Industrial Services | 98.0 | 112 | 349.0 | 349 |

| Miscellaneous | 43.0 | 43 | ||

| Non-Energy Minerals | 101.5 | 169 | 131.0 | 131 |

| Process Industries | 199.8 | 303 | 77.3 | 92 |

| Producer Manufacturing | 143.0 | 366 | 62.0 | 122 |

| Retail Trade | 281.0 | 373 | 869.0 | 869 |

| Technology Services | 173.3 | 526 | 250.8 | 630 |

| Transportation | 119.8 | 188 | ||

| Utilities | 161.5 | 259 | ||

| Total Result | 145.1 | 629 | 144.4 | 869 |

Source: Author's calculations based on Mergerstat data.

Arbitrageurs will analyze the timing for each transaction individually rather than work with averages. However, averages can be useful as a point of reference. Companies indicate most of the time in the press release announcing the merger an anticipated time frame. This time frame always should be an arbitrageur's principal data point. It can be adjusted if, based on analysis and experience, the transaction is likely to take longer. Reasons for extending the time frame can be antitrust issues, uncertain financing, shareholder opposition, or any other potential problem.

Over time, as the merger progresses and new information becomes available, the closing date of the merger must be adjusted if necessary. I have found that in the majority of cases, mergers close faster than the initial indication given in the company's press release. However, as soon as a closing date is extended, the annualized return of a merger drops. Therefore, finding an estimate of the closing date that approaches the actual date reasonably well is critical.

Extension risk affects returns for arbitrageurs in a twofold manner:

- The annualized return on existing arbitrage positions is depressed.

- Spreads will widen, which leads to losses.

To illustrate this problem with numbers, let us return to the acquisition of Autonomy Corporation by Hewlett-Packard discussed in Chapter 2 and assume that instead of November 14, the closing date were to be delayed to January 31, 2012. The potential reasons of such a delay are of no interest for the purposes of this discussion. There would be an extra 78 calendar days until the closing if such a delay were to occur, which almost doubles the time until closing. The total time period for the merger is now 166 days instead of 88, and the annualized return under the compound interest method falls from 10.01 to 5.19 percent:

If, however, the annualized spread were to remain constant at 10.01 percent, the price of the stock would have to decline so that

Therefore, the gross spread would widen by £0.50 to £1.08. Given that the initial spread was only £0.58, this is almost a doubling. Arbitrageurs will suffer losses as a result of the extension. Of course, these losses are only temporary and occur only for those arbitrageurs who are forced to mark to market. Arbitrageurs who report their results only monthly or even less frequently may not even show these losses. If the merger is consummated, the spread will narrow again, and eventually arbitrageurs will recover the marked-to-market losses.

When a deal is extended, both the first and second effects happen simultaneously: Arbitrageurs with existing positions see their realized return shrink and the spread widen. However, the spread is likely to widen much more than the simple mathematical parity of a constant annualized spread as discussed above would suggest. The market perceives the extension of a merger as a signal that the deal may be in trouble. In this case, arbitrageurs will require a higher annualized spread to compensate for the higher perceived risk.

Sometimes the widening can be large briefly intraday and provide trading opportunities. This temporary widening can be caused by sudden selling pressure coming from the uncertainty created by the announcement of the deal extension. If arbitrageurs themselves are sellers, market movements can be swift because the very providers of liquidity have turned into liquidity takers.

Extensions of the time a merger takes to close can also provide additional return if shareholders receive an extra dividend payment. Whether a dividend can be expected is stipulated in the merger agreement. Sometimes merger agreements restrict a company's ability to make dividend payments. In the case of real estate investment trusts (REITs) discussed in the next section, merger agreements often specify that dividends will continue to be paid in amounts sufficient to maintain REIT status until the closing. If an additional dividend is received, it will at least partially offset the reduction in net annualized return that the arbitrageur suffers from the delay. In rare instances, if a company pays very high dividends, or in cases of preferred stock, additional dividend payments actually can boost the net annualized return.

Ticking Fee

Some merger agreements provide for a daily accrual of additional payments if a transaction does not close by a specific date. Such a provision fulfills two purposes: first, it compensates investors for the time value of the delay; second, it acts as a penalty that encourages the buyer to close the transaction promptly.

In the $12.7 billion acquisition of Life Technologies Corporation by Thermo Fisher, delays were expected due to antitrust concerns. In order to force the buyer to resolve any regulatory issues promptly, a daily fee of $0.0062466 per share was going to be added to the merger consideration of $76 after January 14, 2014. The fee is referred to as a ticking fee. This timeline gave the buyer 279 days, or about 9 months after the April 10 merger agreement, which is almost twice the 140-day average that mergers in the health services sector take to close. In the event of a one-month delay beyond that the ticking fee would have added a quarter percent to the merger consideration. This is not a very attractive increase as the annualized spread on the arbitrage traded at around 10 percent to reflect the anti-trust risk of this merger. The actual closing of the transaction occurred on January 31 with a delay of 17 days. Following the announcement of the fulfillment of all antitrust conditions, notably the sale of Life's gene modulation subsidiary to GE Healthcare, the stock closed on January 31 at $76.07, which reflected an increase of $0.106 that resulted from the ticking fee.

Ticking fees are still an oddity, although their increased use reflects the desire of target companies to compensate shareholders of the selling firm to compensate them for delays that can result from antitrust reviews and other complexities in deal structures. For example, when private equity firm Cerberus agreed to acquire supermarket operator Safeway in March 2014, a ticking fee of $0.005342 per day per share was included if the merger were to take longer than one year. This corresponds to an annualized increase of the merger consideration of 6 percent. However, since Safeway was not allowed to pay quarterly dividends after one year, almost half of the ticking fee simply compensated shareholders for the loss of the regular quarterly $0.20/share dividend.

Dividends

Historically, dividends have made a large contribution to the returns achieved by investors in the stock market. With the multiple expansion in the bull market since 1981, the unfavorable tax treatment of dividends relative to capital gains, the widespread use of stock options in management compensation,4 and the widespread acceptance of theories promulgated by two academics, Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller, dividend yields of most indices have fallen to around 2 percent. Mondigliani and Miller show that in a hypothetical world without taxes, investors are indifferent between receiving capital gains and dividends.

Dividends historically have been an important driver of returns earned on stocks until the Modigliani-Miller paradigm became widely accepted and capital gains replaced the role of dividends. For merger arbitrageurs, dividends remain an important element of return.

It was shown in Chapter 4 that merger spreads are usually very small and amount to only a few percentage points. Therefore, dividends that amount to 2 percent per year on average can make a difference; in cases of income-producing stocks, they can present the bulk of the return. In the example of GrainCorp, the annualized return would have been negative without dividends as the trading price reflected the large special dividend that investors stood to receive. When dividends are taken into account the annualized return would have been a more reasonable 7.21 percent rather than negative.

It was also shown in Chapter 2 how dividends complicate stock-for-stock mergers, because an arbitrageur must pay the dividend on the stock sold short. Dividends on the long leg of an arbitrage increase returns; dividends paid on the short leg diminish returns.

In addition to providing additional income, dividends can also alter the tax effect of an arbitrage strategy. The tax treatment of dividends is a science in itself and can become complex when arbitrageurs make cross-border investments. In fact, most countries now impose withholding taxes on foreign investors that can make the difference between an attractive arbitrage opportunity and a not very appealing one. A further complication is added by double-taxation treaties, which may provide exemptions from withholding or the ability to claim back dividends that have been withheld. However, it has been reported that reclaiming withheld dividends is not always smooth and some countries simply fail to fulfill their treaty obligations and do not make restitution, or do so only after multi-year delays.

In the United States, until recent changes in tax rates, dividends used to be taxed as ordinary income, whereas most investors held stocks for long periods of time, so that their capital gains were taxed at a lower tax rate applicable to long-term capital gains. This changed with the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003, which introduced a new lower “qualified” tax rate of 15 percent as long as the stock has been held for more than a 60-day period that includes the dividend date. With the Tax Increase Prevention and Reconciliation Act of 2005, this 15 percent tax rate for dividends has been extended. As of 2013, the tax rate for qualified dividends was increased to 20 percent to match that of the similarly increased tax rate on long-term capital gains. The effect of this change in the tax treatment of dividends is that for long-term holders of a stock, there is no difference in the tax treatment between dividend payments and capital gains (other than second-order effects, such as a potential deferral of the tax payment, or compounding).

However, arbitrageurs are not long-term holders of stocks and therefore experience more complex tax effects. Arbitrageurs have two sources of income: capital gains earned from the spread of the merger and dividends. Most mergers close in less than one year, and under current U.S. tax laws, short-term capital gains are taxed as ordinary income. Under the old tax regime, short-term capital gains and dividends were awarded the same tax treatment, and arbitrageurs were indifferent between generating capital gains or dividend income.

Since the introduction of the favorable tax rate on “qualified” dividends, the situation has changed. Many mergers take longer than 60 days to close, and often arbitrageurs find themselves holding a dividend-paying stock for more than 60 days. These dividends are taxed at a lower “qualified” rate of 20 percent as long as the arbitrageur meets the 60-day holding period requirement. Capital gains continue to be taxed as ordinary income. Therefore, arbitrageurs often have a preference for dividends over capital gains.

When a dividend-paying stock is expected to be held for a long enough period to qualify for the 20 percent tax rate, an arbitrageur will be better off after taxes than with an otherwise identical spread that consists only of capital gains.

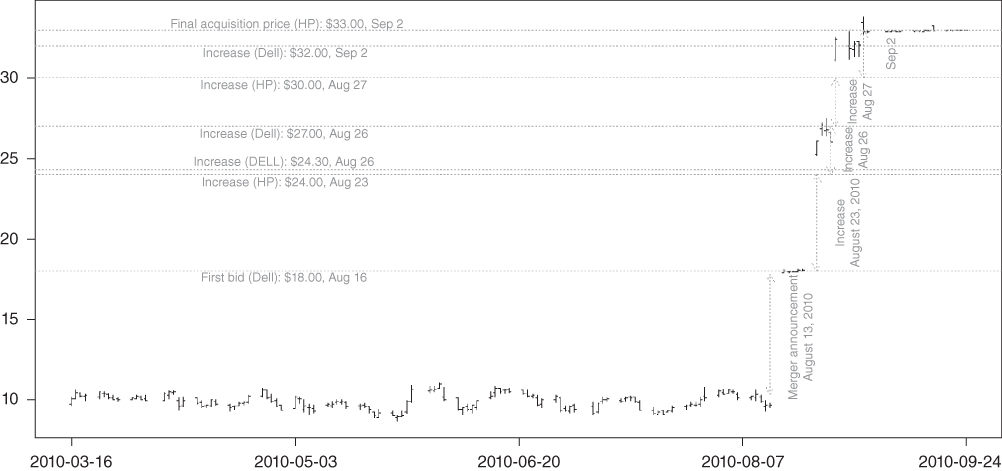

In the case of GrainCorp, the impact of different holding periods has a significant impact on after-tax returns. In the next example, it is assumed that the arbitrageur (or its customer) has a tax rate of 40 percent. This is a reasonable assumption if the client is in the highest federal tax bracket of 35 percent and also pays state and local taxes and possibly also Medicare taxes. If the shares are held for less than 60 days, the entire net spread will be subject to income taxes at 40 percent:

The annualized after-tax return becomes

where

| T is the amount of taxes dues. |

| RANT is the annualized net after-tax return. |

If the shares are held for 60 days and dividends are eligible for taxation at the qualified rate of 20 percent, then the tax impact is reduced by more than half:

This leads to the unusual situation where the investor will experience a tax gain from an arbitrage. Whether or not such a gain can be used in practice will depend on the investor's particular tax situation. In fact, as this company is Australian, a U.S. investor probably would not be able to claim qualified dividend treatment. This example illustrates well how tax effects can alter the profitability of an arbitrage investment and why tax effects must be taken into account.

If a client pays taxes at the rate for the alternative minimum tax, the difference will be less. Many arbitrageurs have tax-exempt clients, such as university endowments or pension funds. In these cases, tax considerations obviously are irrelevant.

Arbitrageurs have to be careful to follow the ex-dates and record dates of dividends correctly. Dividends are paid only to the holders of record on the record date. The payment date is usually two to four weeks after the record date. Shares acquired before the payment date of the dividend, but after its record date, are not eligible to receive a dividend payment.

REIT dividends are a special case: REITs are required to pay out 90 percent of their income to their investors in order to maintain their status as pass-through entities that distribute substantially all income and need not pay taxes at the entity level. REITs are governed by subchapter M of the Internal Revenue Code, which also regulates mutual fund taxation. When a REIT is acquired, it will make a final dividend payment on the day of the closing that is large enough to satisfy the requirement of subchapter M. Shareholders do not normally know the exact amount of the final dividend payment that they can expect. Management guidance often underestimates the actual payment. It also varies with the timing of the merger. The longer the merger takes, the more dividends must be paid out so that the REIT can maintain its status as a pass-through entity. Merger agreements will stipulate whether dividends will continue to be paid. A typical clause specifies that dividends will be paid until the closing in amounts sufficient to maintain REIT status.

Finally, there is one caveat on the availability of the 20 percent rate for dividends on stocks that have been held for more than 60 days: It does not apply to a stock that was acquired from a short seller. Because the short seller pays the dividend on the shorted stock, it is considered a payment in lieu of a dividend, not a dividend paid by the company. Only dividends paid by the company are eligible for the qualified 20 percent rate; payments in lieu of dividends are not. Buyers of heavily shorted stocks must be careful about the nature of their purchase. Fortunately, there is a trick that a buyer can use to convert a long position in borrowed shares into a long position of unencumbered shares: Request the issuance of a physical certificate. There is a cost involved, not to mention the risk of loss and the effort required to handle certificates. More important, it can be difficult to sell the shares (short sales are a temporary fix, though). However, if an arbitrageur has a sufficiently large holding of a stock, it may be worthwhile taking the extra step to optimize taxes.

Short Sales as a Hedge and an Element of Return

Short sales are one of the trickier aspects of merger arbitrage that warrant special consideration. Short sales are performed as one leg of a stock-for-stock merger arbitrage. This was described in principle in the example of the CGI Mining/B2Gold Corp merger in Chapter 2. It is often said that shorting requires special skill; whether we call it a skill or not, it is true that shorting requires special attention and is one of the most regulated aspects of stock trading.

In the sense that shorts are entered as part of a two-legged position, merger arbitrage short positions can be said to be hedged. But the hedge works only while the merger is on track to close. If uncertainty about the closing increases, the short will no longer be hedged and will take on a life of its own.

In order to sell a stock short, an arbitrageur must be able to deliver it. Since the arbitrageur does not own the stock, it must be borrowed from an owner. To borrow shares, an arbitrageur or its broker contacts some of the large clearing firms, which will lend their customers' securities. Institutions that custody their assets with a bank custodian often have their own stock lending desk in order to generate additional revenue. Retail investors can short out of the inventory of their broker's clearing firm.

The cost of borrowing is generally included in the short rebate paid by the broker that handles the short. In the event that an arbitrageur borrows stock elsewhere, it may have to pay a separate fee. The short rebate was discussed previously in the context of the CGI Mining/B2Gold Corp stock-for-stock arbitrage.

The short rebate makes an important contribution to arbitrageurs' returns. Short rebates vary slightly from broker to broker. Large arbitrageurs will obtain higher short rebates than smaller ones. Many retail brokerage firms do not pay their customers a short rebate at all. The example of the CGI Mining/B2Gold Corp stock-for-stock arbitrage from Chapter 2 will be used to illustrate how returns can be affected by different levels of the short rebate.

In the example given in Chapter 2, it was assumed that the arbitrageur would earn a short rebate of only 1 percent, amounting to $11.21 over a period of 140 days on $2,923 of short proceeds. This represented an increase of almost 18 percent over the annualized net spread that excludes the short rebate. In late 2012, interest rates were at record lows, and a short rebate of 1 percent is a reasonable assumption. When interest rates are higher in more normal times, short rebates paid by brokerage firms will also be higher and make a larger contribution to an arbitrageur's annualized return.

To calculate the impact of the short rebate in a pure stock-for-stock merger, the rate of the short rebate can simply be added to the annualized net return as a shorthand calculation. In a mixed cash/stock merger, the short rebate must be reduced by the ratio of cash to stock and then added to the annualized return. These two calculations are not accurate but are good enough for most purposes.

For a more accurate calculation, the short rebate must be calculated on the dollar amount sold short, as was done in the CGI Mining/B2Gold example in Chapter 2. Table 5.5 shows how the annualized return on the arbitrage would have improved for different levels of the short rebate. The interest earned is based on the amount of $2,923 sold short and the annualized return without incorporation of the short rebate is 5.85 percent. For a short rebate of 5.43 percent, the annualized return doubles compared to the return without a short rebate.

Table 5.5 Improvement in the Arbitrage Spread of the CGI Mining/B2Gold Stock-for-Stock Merger for Different Levels of Short Rebates

| Short Rebate (%) | Interest Earned ($) | Increase in Spread (%) | Annualized Return (%) | Increase in Annualized Return (%) |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.85 | 0 |

| 0.5 | 5.61 | 8.90 | 6.38 | 9.1 |

| 1 | 11.21 | 17.80 | 6.91 | 18.2 |

| 1.5 | 16.82 | 26.69 | 7.44 | 27.3 |

| 2 | 22.42 | 35.59 | 7.98 | 36.4 |

| 2.5 | 28.03 | 44.49 | 8.51 | 45.6 |

| 3 | 33.63 | 53.39 | 9.05 | 54.8 |

| 3.5 | 39.24 | 62.29 | 9.59 | 64.1 |

| 4 | 44.85 | 71.18 | 10.13 | 73.3 |

| 4.5 | 50.45 | 80.08 | 10.67 | 82.6 |

| 5 | 56.06 | 88.98 | 11.22 | 91.9 |

| 5.43 | 60.88 | 96.63 | 11.69 | 100.0 |

| 5.5 | 61.66 | 97.88 | 11.77 | 101.3 |

| 6 | 67.27 | 106.78 | 12.31 | 110.7 |

| 6.5 | 72.87 | 115.67 | 12.86 | 120.1 |

| 7 | 78.48 | 124.57 | 13.41 | 129.5 |

| 7.5 | 84.09 | 133.47 | 13.97 | 139.0 |

| 8 | 89.69 | 142.37 | 14.52 | 148.5 |

In mergers that pay a combination of cash and stock, the dollar amount sold short is much smaller than in a pure stock-for-stock merger. If the cash component is very large, the transaction will provide almost no short rebate.

The gross spread reflects the ability of arbitrageurs to earn additional income through the short rebate. Cash mergers have wider spreads in part because arbitrageurs cannot earn a short rebate and in part because the risk profile is higher due to the risk associated with financing the cash consideration.

A high risk with borrowing shares lies in the propensity of the original owners to ask for the return of their shares at a time that is inopportune for the borrower. The owners may ask for their shares back, for example, because they want to sell their position. When they sell, they will have to deliver their shares to the new owner. The arbitrageur then has only two choices: find another counterparty from which the shares can be borrowed, or cover the short. When many short sellers are required to close their position at the same time, a short squeeze ensues. In a short squeeze, a heavily shorted stock suddenly rallies abruptly. A good sign that a rally is a short squeeze rather than an upside revision by the market of the intrinsic value of a stock is the absence of any fundamental information.

The short seller of a stock must make dividend payments to the buyer. When a short seller borrows shares and sells them short, there are now two owners of the stock: the original owner who has lent the shares, and the counterparty to the short sale. Both are long stock and expect to receive dividends. However, only one dividend payment is made by the company underlying the stock. The dividend payment going to the counterparty of the short sale must be made by the short seller. For most investors, the clearing broker that holds the short position will administer the payment and debit the account directly. We mentioned earlier that this payment in lieu of a dividend is not eligible for the “qualified” tax rate of 20 percent on dividends. Instead, it is taxed as ordinary income even if the shares were held for more than 60 days.

Paying dividends on shorted stock is a cost of carry of the position. The higher the dividend yield, the higher the cost of carry. In theory, stocks respond to the payment of a dividend by dropping by the dividend amount on the ex-date. However, dividends are paid out of income, so that companies with large dividend payments tend to be profitable and do not drop as much, certainly not in the long run.5 A quick way to estimate on the back of an envelope the carry for a stock-for-stock merger arbitrage is by comparing the dividend yields of the two stocks.

- If the long position has a higher dividend yield than the short, the position has a negative carry and dividends improve the spread. If the spread were to remain constant, the arbitrageur would earn the differential in dividend yields.

- If the long position has a lower dividend yield than the short, then the position has a positive carry. If the spread were to remain constant, the arbitrageur would have to pay the differential in dividend yields.

This method is a rough estimate only. A more careful estimation of the carry needs to take the exact timing of the dividends into account as well as the anticipated closing of the merger. Future dividend dates and amounts can be extrapolated from historical dividends.

A more extensive discussion about short selling can be found in Chapter 14.

Leverage Boosts Returns

Merger arbitrageurs are no different from other investors in their desire to boost returns by borrowing. It is appropriate and safe to use leverage when the investments financed have low volatility, such as real estate, fixed income, or private equity. Merger arbitrage is one such low-volatility strategy.

There are two principal ways allowing arbitrageurs to use leverage: through the use of margin or other borrowings, or via derivatives. The two ways differ not only in economic terms but also in the approach taken to evaluate their effect. Derivatives are acquired in connection with specific investments and provide leverage on those investments only, whereas margin or other borrowings are taken against the portfolio as a whole and cannot normally be attributed to a specific arbitrage opportunity.

Margin borrowing is the classic but expensive way to leverage a portfolio. In margin borrowing, an arbitrageur borrows money from a broker and pledges the securities acquired as collateral. In most cases, arbitrageurs obtain this form of financing from their prime broker. The prime broker borrows funds in the money market, or uses funds deposited by other customers, and lends them to arbitrageurs. Proceeds from customers' short sales are another source of funds. Prime brokers effectively are acting as banks for securities traders. Like a bank, the prime broker makes a profit because it lends for a higher rate than it borrows at.

In the United States, due to the more volatile nature of securities markets, the Federal Reserve has imposed capital requirements not only on the brokers but also on the customers who borrow on margin. Under Regulation T, a customer must have at least 50 percent equity when acquiring a security. This criterion is also known as the initial margin requirement. Because securities prices fluctuate so much, the capital requirement for ongoing borrowings is much lower than for the initial margin. After the security has been acquired, a customer must maintain at least 25 percent of the account value in equity, the maintenance margin. This allows for a significant drop in the value of a portfolio. If the equity falls below the maintenance margin requirement, the broker will issue a margin call that forces the customer either to sell securities or to inject additional funds into the account. If a customer fails to do either, the broker will liquidate positions until the maintenance margin is restored. Brokers are free to set more stringent margin requirements, and many do so to protect themselves and their customers from volatility.

Portfolio margining is another way to overcome restrictions on the use of leverage. Rather than being based on the national amount as under Reg T, leverage in such an account is risk-based, where risk offsets are applied across pairs of securities. For example, a portion of the long position in one security can be used to offset the risk of a short position in another stock. For customers with prime brokerage accounts, the minimum account size is $500,000 (for retail accounts, $100,000) in order to benefit from portfolio margining, although many brokerage firms apply higher minimum requirements.

Another way to increase leverage is to establish a joint back-office account. Here, ownership of the account is shared between an investor and its clearing firm. As this is now considered a brokerage firm's account, Reg T does not apply and even higher levels of leverage than with portfolio margining can be achieved. It is said that leverage of 30:1 is possible for accounts holding positions that largely offset each other. Such accounts pose little risk. Presumably, merger arbitrageurs would not be considered a pure enough arbitrage and hence not be eligible for leverage at such an extreme level.

Outside the United States, capital requirements vary. Until recently, many U.S. investors used margin accounts in Europe to gain leverage because regulators there had a more cavalier approach to leverage than their U.S. counterparts. At the time of this writing, it is unclear whether regulation of margin borrowing will become more akin to that in the United States.

The use of borrowings other than through margin is open only to some of the larger arbitrageurs. Investment banks that run arbitrage books can borrow at a small spread to the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR). Their cost of capital typically is allocated on a corporate level under a blended rate of one form or another to each business unit, and the arbitrage desk will be assigned a cost of capital. Imitating investment banks, some large hedge funds recently have tapped the capital markets and issued bonds in order to have access to permanent capital independently of the availability of margin borrowing from brokerage firms. It is clear that the economics of leverage is much more favorable for large operations with access to such a varied array of funding sources at attractive spreads.

Funding arbitrage and other hedge funds has become a very profitable business for prime brokers. Many brokers make more than half of their income from the funding spread between their cost of capital and the margin rate. The other half is made through commissions. The high profitability of margin borrowing to prime brokers is a corollary of the method's expensive nature.

In addition to its high cost, arbitrageurs using margin also make themselves dependent on the business prospects of their prime broker. During the credit crisis of 2007–2008, many hedge funds were forced by their prime brokers to reduce leverage because the brokers themselves suffered losses and needed to reduce their exposure to risky customers. When many customers, including merger arbitrageurs, were forced to sell their holdings, spreads widened on a wide variety of arbitrage strategies, not just merger arbitrage. This had nothing to do with the inherent risk of these transactions increasing; it was caused only by the actions of the arbitrageurs, who are normally liquidity providers. In this case, they became liquidity takers.

Covered Call Writing

A popular technique for enhancing returns on stock positions is the writing of covered calls. The idea is that an investor holds a stock and by writing a call option against that stock, additional income can be generated. I have come across several financial advisers who recommend this strategy to their customers.

Covered call writing is more complex than many of its proponents admit. Owning a stock and writing a call against it limits the upside: If at expiration the stock price rises above the strike price of the option, the stock will be called (see Figure 5.7). Conversely, if the stock price drops, the option will expire worthless, so that the investor can keep the premium as a profit. But the holder of this position will suffer a loss on the stock that probably will exceed the premium income. This payout profile resembles that of a short put position. When an investor writes a put, the upside is limited to the premium received. However, the downside is practically unlimited. The only limitation is that the underlying stock cannot fall below zero. Many investors are not aware that by writing a covered call, their effective position is identical to writing a naked put. Nevertheless, covered call writing is peddled as a conservative strategy. Most conservative investors would never write a naked put if asked to do so by their financial adviser.

Figure 5.7 Covered Call Writing

For a merger arbitrageur, covered call writing makes more sense than for a buy-and-hold investor. In a cash merger, the upside is limited anyway to the buyout price. Adding an additional limitation to the upside through a written call will not affect the payoff profile in any way. Readers are reminded of Figures 1.7 and 1.8, which show that merger arbitrage has a payoff pattern that resembles that of a put option. If the long stock position is supplemented with a covered call, the arbitrageur creates a parallel put exposure in addition to the implicit put created by the arbitrage. However, the risk is not cumulative. The downside risk comes only from the long position in the stock. The written call only limits the upside, which is already limited by the presence of an acquisition proposal.

Covered call writing should be considered only for cash mergers. If the long leg of a stock-for-stock merger were to be used as cover for a call, the stock price of both the long and short might rise. But the long leg of the arbitrage will be called when it rises above the strike price of the written call. This would expose the arbitrageur to losses from the short position. Both the long and short leg are supposed to move in sync when their prices increase, and covered call writing disrupts this principle.

So can covered call writing add extra income to an arbitrage position? Unfortunately, there is no such easy way to make money. First, option premia tend to drop significantly once a merger has been announced. Second, by writing a covered call, the arbitrageur limits the ability to participate in any increase in the acquisition price if, for example, another buyer were to emerge offering a higher price.

Options are priced based on the fluctuation of the underlying stock—its volatility. The higher the volatility, the higher the time value of the option. Once a merger is announced, volatility tends to drop significantly. This effect was discussed in more detail in Chapter 3. Market makers for options are aware that the underlying stock will soon cease to exist and price the options accordingly. Figure 5.8(a) shows the implied volatility of options of Superior Essex Inc., which was acquired by Seoul-based LS Cable in August 2008, for a period of one year prior to the acquisition. For the time leading up to the June 11, 2008, announcement of the merger, Superior Essex call and put options traded at implied volatilities mostly between 40 and 50 percent, temporarily shooting up to 60 percent. After the merger agreement was announced publicly on June 11, implied volatility dropped to between 5 and 20 percent. The associated option volume is shown in Figure 5.8(b).

Figure 5.8 (a) Implied Volatility and (b) Option Trading Volume of Superior Essex Inc.

As a result of the sharp drop in option volatility, premia drop to levels that make covered call writing unattractive. Only the writing of long-dated call options can in some instances generate noticeable additional returns, because the additional time value increases the premium.

It should also be noted from Figure 5.8(a) that implied volatilities for call and put options track each other very closely. Due to call-put parity, implied volatilities should be close for calls and puts. This shows that the option markets remain efficient even when a company is about to be delisted.

Commissions and Portfolio Turnover

Since fixed commissions were abolished in the United States on May 1, 1975, the cost of executing stock trades has dropped almost every year. The “May Day” of 1975 may have been the trigger, but the biggest enabler of the drop in commission has been technology. The securities markets are becoming increasingly disintermediated. While it was common during the 1990s to place trades via a telephone with a broker, software applications provide today's investors direct access to the various execution venues with split-second order transmission.

The average commission in 1980 was close to $0.40 per share and has dropped to roughly $0.05 per share in 2003, according to data by Greenwich Associates. Today, low-cost commissions of direct access providers are even lower, amounting to less than $0.01 per share. Some brokerage firms offer flat-rate tickets for low-priced shares, where $0.01 would constitute a larger percentage of the stock's price than for a typical stock priced at $20.00.

For arbitrageurs, this development has been positive for two reasons:

- The drop in the price of commissions has helped to maintain profitability of merger arbitrage spreads.

- Technological improvements have improved the placement of orders and decreased the risk of trading errors.

In the examples of merger arbitrage investments discussed in Chapter 2, the dollar amounts and percentages of spreads were always very small. An overview of the spreads is shown in Table 5.6.

| Transaction | Absolute Spread | % Spread (%) | Annualized Return (%) |

| Autonomy/HP | £0.58 | 2.33 | 6.74 |

| CGI Mining/B2Gold | C$0.063 | 2.2 | 5.0 |

| Alterra Capital/Markel | US$0.62 | 2.17 | 4.14 |