Chapter 11

Managing Risk in Your Programme

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding the principles of risk management

Understanding the principles of risk management

![]() Taking a perspective on risks in different parts of the programme

Taking a perspective on risks in different parts of the programme

![]() Using the risk-management approach

Using the risk-management approach

![]() Applying the risk-management process

Applying the risk-management process

By definition, any activity (such as your shiny new programme) that seeks to achieve benefits through change is going to include a certain level of uncertainty ‒ in other words, risk. You can't avoid this reality. Risk isn't something to avoid at all costs (like saying, ‘Do you want me to drive?’ when your partner is fuming behind the wheel after taking yet another wrong turn), which is why I call this chapter ‘Managing Risk in Your Programme’ and not ‘Avoiding Risk in Your Programme’.

Risk management is a big subject, and in this chapter I take a broad look at risks in the context of a programme. Plenty of risks can arise within a typical programme, so as well as covering the principles and terminology used, I also discuss the perspectives, which are the different parts of the business in which risks can appear (this practice is quite different from project risk management). When running a programme you're constantly judging whether you need to manage risk in one perspective or another.

In addition, I cover the risk management approach (another name for all the risk documents that you can use) and I look at the processes you can follow when you're managing risks.

Introducing the Basics: Risks and Issues in a Programme Context

Crucial to dealing effectively with the risks that your programme faces is understanding the difference between a risk and an issue:

- Risk: An uncertain event or set of events that may affect you in achieving your programme's objectives. You state a risk in terms of the probability of the threat or opportunity. Don't forget upside risks by the way, which can be called opportunities. For example, if this book is very popular, I'll get lots of invitations to speak at conferences. It's still a risk, despite being a nice problem to have.

You calculate the size of a risk as follows:

Probability of Threat or Opportunity × Magnitude of Impact

- Issue: An unplanned event that occurs and requires management action because it affects the programme. An issue can be a problem, query, concern, change request or risk.

Sitting at the centre of the programme you're interested in are risks and issues that matter to you and come from those parts of the environment where the programme is having an effect. Here are a few examples:

- Benefits and transition.

- Dependencies, constraints and quality that don't affect just one isolated part of the programme but are common across a number of areas.

- Common and above-project risks and issues.

- Stakeholders including staff and third parties.

- Circumstances where operational performance can be degraded.

- Where ambiguity about states exists (states are a description of the future described in the Blueprint – refer to Chapter 6).

Viewing programme risk in context

A programme's context is necessarily complex, dynamic and uncertain. Indeed, you want to maintain a certain level of uncertainty within the programme in order to maximise innovation and allow for a flexible boundary (I discuss the boundary to the programme in more detail in Chapter 4 about principles, and Chapter 7, where I look at the documents where you describe the programme boundary). Therefore you need to manage and tolerate uncertainty, complexity and perhaps even ambiguity.

Getting risk clear: Basic phraseology

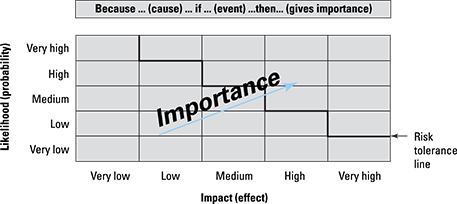

I audit lots of Risk Registers (which I define in the later section ‘Gotcha! Capturing risks with the Risk Register’) and one of the largest and most common mistakes I see is that the risks aren't stated in a clear and unambiguous way. Therefore I find the basic language of risk, as shown in Figure 11-1, invaluable. If you're already an expert on risk, you can skip this section.

Figure 11-1 is called a probability impact grid on which you can plot the likelihood of the risk vertically and the impact of the effect of the risk horizontally. When you add the risks it's called a Summary Risk Profile.

You use a scale or standard, which you need to define, using terms such as very low, low, medium, high and very high. Each of those bands doesn't have to be of equal size. For example, very low probability can be from 0 per cent to 20 per cent, while very high probability can be a smaller band running from 95 per cent to 99.9 per cent. Also on the impact scale you need to have different standards for each class of risk. So reputational risk can have one set of definitions and financial risk a different set.

The stepped risk tolerance line indicates the point above which risks must be escalated to the next level of management.

Figure 11-1: Risk – basic phraseology.

Thinking about Risk-Management Principles and Terminology

I describe the programme management principles in Chapter 4 and a similar set of principles are associated with risk management. I share some of them with you in this section.

Meeting the principles: M_o_R

The principles of risk management are taken from a sister method to MSP called M_o_R (Management of Risk). These principles fit nicely with the way you want to run your programme and the principles of programme management as follows:

- You need to make sure risk management is aligned with organizational objectives. Clearly a parallel exists here with the MSP principle of remaining aligned with corporate strategy.

- The Risk Management Strategy must be designed to fit the current context (flip to the later section ‘Defining required activities: Risk Management Strategy’). In other words, you need to put in place sufficient risk management to be appropriate for whatever you're doing, in this case running a programme.

- Your approach to risk management needs to engage stakeholders and deal with the differing perceptions of risk from the different stakeholder communities. As I cover in more detail in Chapter 14, you consider the different stakeholder groups with an interest in your programme (as you're aware, a diversity of stakeholder groups exists within a programme). Stakeholders have a good idea of what risk may appear in their area and be pretty good at judging the size of those risks. You can accept their opinions on new risks and their size without questioning them too much, and if their view is different from yours, a consensus will emerge as you go through the risk-management process.

- You need to provide clear and coherent guidance to stakeholders on how to undertake risk management within your programme. The document set within MSP makes aligning with this principle easy. You create a Risk Management Strategy and produce Risk Registers. Individual projects and business areas may even publish their own risk management strategies, so you can ensure sufficient local advice on how to carry out risk management.

- The next principle is that risk management needs to inform decision-making. Risk management can all too easily exist in a bubble. If it's seen as an end in itself, risk management rapidly becomes a tick-box exercise ‒ an extra piece of bolt-on bureaucracy. You have to link risk management to decision-making across the programme so that better decisions can be made.

- Risk management should facilitate learning and continuous improvement. You need to use the historical data that you're accumulating about risk management to encourage continual improvement. Clearly a strong link applies to the programme management principle of learning from experience.

- Risk management needs to recognise uncertainty and support considered risk-taking ‒ a supportive culture. If whenever you say to the boss ‘I've spotted a risk’, the boss tells you off and says, ‘Risks aren't allowed to exist in my programme’, you aren't going to achieve successful risk management. So you need to create a supportive culture that recognises the existence of uncertainty. A programme, remember, supports considered risk-taking.

You can never mitigate all risks; all you can ever do is select certain risks and mitigate them even though some still occur.

You can never mitigate all risks; all you can ever do is select certain risks and mitigate them even though some still occur. - The final and some argue the most important risk-management principle is that risk management needs to achieve measurable value. You're only doing risk management in order to achieve the goals of the programme. Again a strong link can be made here to the programme management principle of adding value.

Talking the talk: Risk terminology

Several pieces of useful terminology exist in connection with risk management.

Risk appetite

Risk appetite is the amount of risk an organization is willing to accept. In other words, is the organization comfortable taking risks or is it risk averse? When you know the organization's risk appetite you can create your programme Risk Management Strategy (for detail, see ‘Defining required activities: Risk Management Strategy’ later in this chapter). The risk appetite steers risk management activities because it helps you define your delegation and escalation rules. This approach helps you insulate the programme from unwelcome surprises and define clear risk tolerances.

- Translate the risk appetite into objective guidelines.

- Define the exposure that, if exceeded, requires escalation and reaction.

- Need to be in line with the programme objectives.

Assumptions

Therefore, when you state a set of assumptions they help to clarify the boundary of the programme. You can consider assumptions to be potential sources of risks. Because assumptions are related to the programme boundary, you probably want to review the related risks at programme level.

Early warning indicators

Early warning indicators are performance indicators that lead, rather than lag, a change in the situation. They're used for all sorts of purposes throughout business as usual.

If you're going to take the time and trouble to track early warning indicators, remember that they're of value only if:

- You track valid indicators.

- You look at them regularly.

- They're accurate.

- You act on them.

Threats, opportunities, events and effects

The same event can be both a threat and an opportunity and therefore give rise to several risks. As you think more about risks you begin to separate events from effects. One event can trigger several effects, and an effect can be triggered by several different events. In the same way, the causes of a risk can lead to several different risks, or the same risk can arise from several different situations.

Also, an event can have different effects in different parts of the programme.

Proximity

You normally express risk in terms of two factors: probability and impact (as I explain in the earlier section ‘Getting risk clear: Basic phraseology’). Sometimes, however, a third factor is useful: a time factor ‒ the proximity. You use it when the risk is expected to occur at a particular time. So the severity of the overall impact of the risk varies depending on when the risk occurs.

Knowing the proximity and factoring it into the assessment of the risk has an effect on the urgency with which you take action, the nature of the response, what triggers the response and the timing of the response.

Proximity is particularly useful because a programme is likely to be long and some risks you identify aren't going to happen for a long time. If you give them a low proximity score, you record them but don't have to deal with them yet (check out the nearby sidebar ‘Getting IT right’ for a real-life example).

Risk owner and risk actionee

As with so much in programme management, you want to be clear about terms:

- Risk owner: Named individual responsible for the management and control of all aspects of a risk.

- Risk actionee: Named individual assigned to implement the risk response action; this person supports and takes direction from the risk owner.

For more detail about who's responsible for the different aspects of risk (and issue) management, check out Chapter 12.

Risk aggregation

As risks pass up to the strategic level and down to projects some of them stick at programme level. You have to gather together the effect of risks from different sources at programme level.

- Accumulate

- Grow (the sum is greater than the parts)

- Reduce (the sum is less than the parts)

Also, apparently independent risks can have a cascade effect: they can trigger other risks or increase or diminish the effect of other risks. As Programme Manager you're the right person to examine carefully the aggregated risks.

You need to consider factors such as the timing of related risks and their overall impact. You need to look at the overall cost of mitigation actions and think about whether mitigation is to be carried out at programme level or locally.

Dealing with Risk in Four Perspectives

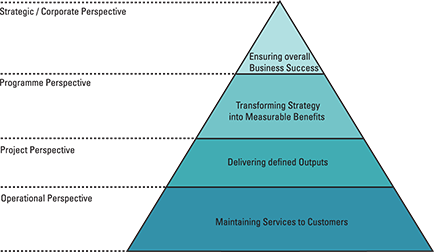

Management of Risk (which I introduce in the earlier section ‘Meeting the principles: M_o_R’) looks at risk management from four perspectives: strategic (or corporate), programme, project and operational. See Figure 11-2 for an illustration of the hierarchy. You can add a fifth portfolio perspective if someone is running portfolio management in your organization.

I look at the types of risk that appear at each perspective and how in a programme you pass risks from perspective to perspective so that the right people can handle them.

Figure 11-2: Organiza-tional management hierarchy.

- Strategy. The strategic perspective means looking outside the programme at the business or even outside the business at the external environment. It often has a longer-term focus. You may identify risks at the programme level that need to be escalated to the strategic level and you can also argue that the programme came into existence to deal with specific strategic-level risks.

- Programme. Your focus is on the programme perspective. Risks in this area are risks to the programme: for example, risks to benefits, outcomes, the Blueprint and execution of the programme. You can see this in terms of interrelationships: from the programme perspective you may need to escalate risks to the strategic level or pass them down to projects or the operational perspective.

- Project. The project perspective concerns risks relating to project delivery. You can think about typical project constraints such as time, cost, quality and so on. Project risk may have to be escalated to the programme or you may want to pass them across to the operational world. You hope that the relationships within the programme organization structure make doing so more straightforward.

- Operational. The operational perspective is concerned with risks to business as usual. You can if you like call this the ‘business as usual’ perspective. From the operational level operational risk owners may delegate risks to projects or they may escalate them to the strategic level.

Surveying the typical risks to a programme

Your programme doesn't have to deal only with programme risks; you may also need to get involved with risks that rightly sit in other perspectives. Here are some areas where different types of risks might arise:

- Strategic-level risks:

- Other programmes

- Political pressures

- Programme-level risks:

- Changing requirements

- Inter-project dependencies

- Project-level risks:

- Changing requirements

- Resource availability

- Operational-level risks:

- Transfer to operations

- Organizational acceptance

Thinking about programme risks and issues

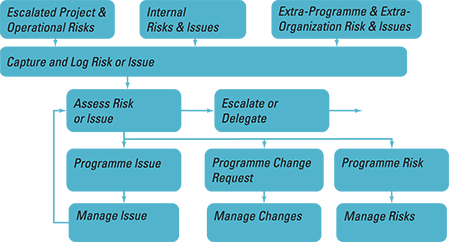

Figure 11-3 is a simple diagram that allows you to consider the flow of risks and issues within the programme. But don't get too deeply into the detail of this diagram because it's not an explicit process model ‒ it's just a set of concepts.

Figure 11-3: Risk and issue management.

I want to give you a feel for the complexity of risk and issue management at programme level. The following list gives you a little more insight into how risks move around within a programme:

- Risks may be escalated from projects or from business as usual.

- The people at the centre of the programme themselves identify risks and issues, and therefore some are internally generated from, say, the Programme Office.

- You also get risks from outside the programme but still within the business and perhaps even from outside the organization. So you also have to pick up risks and issues from these broader areas of interest.

You need a capability to assess all these risks or issues. Part of the assessment is considering where you can best manage the risks. You can deal with them at programme level or escalate them or delegate them. You can have a whole series of escalation and delegation routes that you have to document.

The risks and issues at your level can take different forms when assessed. Perhaps something is a programme issue that you need to manage, which may in turn trigger other risks and issues. This issue may be a change request that you need to manage, assessing it, considering it at the right body (a committee or working group, for example) and executing the change if action is approved.

If it's a programme risk, of course you use your risk-management process to manage it.

Distinguishing programme and project risks

You need to be absolutely clear on the difference between programme and project risks and ensure that your projects have the same understanding. In Figure 11-4, I envisage risks as being like satellites moving between the Earth's and the Moon's orbit. Sometimes you need to boost the satellite out of the Earth's orbit into an orbit around the Moon; sometimes a satellite in orbit around the Moon needs to come back to the Earth (if this doesn't make sense, read Rocket Science For Dummies!).

Figure 11-4: Programme and project risks: red circles represent individual risks.

- Project risk: Within the span of control of a project that belongs to your programme, for example, time, quality or cost:

- An intra-project, that is, one with no impact outside of the project.

- Programme risk: Outside the span of control of a project that belongs to your programme:

- An inter-project, for example, dependencies.

- An extra-project, for example, external factors.

- Threats to the achievement of programme benefits.

Investigating interrelationships between different organizational perspectives

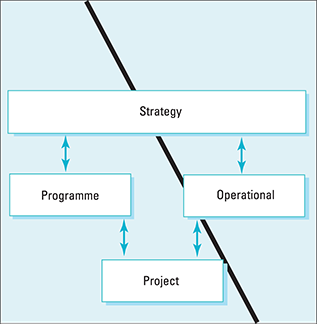

The whole idea of risks passing between perspectives gets more complex than even the preceding three sections may imply, because not all risks pass through the programme. So, for example, they may pass directly between the strategic and operational perspectives. Take a look at Figure 11-5, where the diagonal black line indicates the boundary between change and business as usual.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 11-5: Interrela-tionships between different organizational perspectives.

I discuss the interrelations of the four perspectives in the following four sections.

Strategic risk and issue sources

Strategic risks and issues are going to be external to the programme. So they can be events that are externally triggered from beyond the business or just from outside your programme. If you're considering strategic risks from outside the programme, they can be triggered by other programmes just as you can be generating strategic risks for other programmes. Also certain risks and issues can occur between your programme and other programmes. Typically these involve inter-programme dependencies.

But other things that are going on in the business may not be as well structured as a programme. They may simply be cross-organizational initiatives: things happening across the business. For example, if the business is engaged with a third party and something happens in that third party, say a supplier goes bankrupt, that gives rise to strategic issues and risks that you have to consider within the programme.

Another category you need to consider is internal policies. By that I mean those internal to the business, internal to the organization if you like, not internal to the programme. For example, perhaps the finance director issues a new policy on accounting that gives rise to risks and issues in the way you carry out your financial management.

Programme risk and issue sources

Here's quite a long list of sources of programme-level risks and issues:

- Aggregated project threats. They may simply be individual project threats and opportunities or the total of a number of project threats.

- Lack of senior management consensus. If senior managers don't agree on the direction of the programme, they may find making decisions more difficult, or may take decisions that don't help the programme.

- Lack of benefits clarity or buy-in. Among those who should be owning and championing the benefits.

- Cross-organizational complexity. Perhaps the sheer complexity of what's going on across the organization ‒ the complexity that you're triggering by carrying out the programme ‒ gives rise to issues and risks.

Interdependencies. A key source of programme issues and risks. Indeed, when you're controlling the programme you want to keep the closest track of interdependencies.

Interdependencies. A key source of programme issues and risks. Indeed, when you're controlling the programme you want to keep the closest track of interdependencies.- Funding uncertainty. Perhaps over-funding.

- Unrealistic timescales. This can happen in project world or business as usual. An example from business as usual is if Business Change Managers underestimate the time taken to achieve transition, then benefit realization may be delayed.

- Resource availability. Non-availability of resources is a fertile source of programme-level issues and risks.

Project risk and issue sources

The sources of project-level issues and risks can be ones that you delegate down to the projects. Or they may occur in the project and you need simply to ensure that you deal with them within the projects.

- Lack of clarity on customer requirements within a project

- Lack of availability of resources within a project that affects one project but not a series of projects across the programme

- Timescales

- Quality expectations

- Project drifting off track because of limited visibility of the Blueprint within the project

- Procurement problems

- Scheduling problems

- Lack of visibility of programme-level risks

Operational risk and issue sources

Examples of operational risks and issues may be that business as usual managers, perhaps those who aren't Business Change Managers but are their colleagues, regard the programme as being their biggest source of risks and issues.

- Quality of benefit-enabling outputs. The outputs that you're creating enable benefits to be realized that aren't of an appropriate quality.

- Cultural issues. Perhaps you're trying to change the culture more significantly then you appreciate.

- Affecting business continuity. If an output coming from a project works in the test environment in the project, but it isn't really suitable for the businesses, then existing business-as-usual operations may be disrupted.

- Ability of operations to cope with outputs. Overloading operations so that they don't have time to concentrate on business as usual while also coping with the capabilities you're providing.

- Commitment. Perhaps commitment to the programme within the operational area declines.

- Stakeholder support. Stakeholders who aren't really committed to the programme may not be a problem initially. But if, later on, you need them to really get behind the programme and make some changes in their environment and they're a bit lukewarm, then they won't make the necessary changes.

- Industrial relations. If you can't reach an agreement with trade unions they may take actions that prevent you from changing business as usual.

- Availability of resources. Within the operational area.

- Track record in not managing change successfully within the operational area. If the business hasn't been successful managing changes directly, you may face a fair amount of cynicism about your programme.

You can group several of these topics together under a heading of the rate of change. Maybe the rate of change that you're imposing on operations is just too great.

Documenting the Risk-Management Approach

The risk-management approach is just another term for the risk-management documentation. In this section I share with you the purpose and composition of three risk documents that you need in your programme.

For details on another document ‒ the Probability Impact Grid/Summary Risk Profile ‒ flip to the earlier ‘Getting risk clear: Basic phraseology’ section.

Defining required activities: Risk Management Strategy

The purpose of the Risk Management Strategy is to define and establish the required activities and responsibilities for managing the programme's risks.

The typical content covers: how to identify risks, responses and actions; how to handle risk ownership; how to make and implement decisions (for example, the tolerance you're delegating to others); how to monitor and evaluate actions and communication mechanisms.

More specifically, the Risk Management Strategy features the following:

- Assessing the effectiveness of risk management

- Early warning indicators (for an explanation, check out the earlier ‘Talking the talk: Risk terminology’ section)

- Escalation criteria

- How proximity is assessed

- How to calculate expected value

- Information flows and reporting

- Relevant standards

- Risk response category

- Roles and responsibilities

- Process

- Scales for estimating probability and impact

- Techniques

- The links between risk management and benefits management

- The templates you're going to use for documents like Risk Registers

- Timing of risk-management activities

Gotcha! Capturing risks with the Risk Register

- Risk identifier

- Risk description

- Probability

- Programme impact

- Proximity

- Response description

- Residual risk

- Risk owner and risk actionee

- Response type

- Current status

- Cross-reference to plan

Monitoring risks: Risk Progress Report

- Action:

- Progress

- Effectiveness

- Trend analysis

- Contingency spend (money put aside to spend on dealing with risks)

- Number of risks emerging by:

- Category

- Project

- Anticipated risks

- The movement of relevant indicators against their target values

Following the Risk-Management Process

Figure 11-6 depicts the risk-management process, taken from M_o_R. The steps in this cycle and the transformational flow have no rigid links between them. I see each of these process steps happening on many occasions within each MSP transformational flow process. (I introduce the processes within the MSP transformational flow in Chapter 1.)

Figure 11-6: Programme risk-management cycle.

Communicate

Communication is an on-going activity during risk management. By communicating with the relevant stakeholders you're constantly identifying new risks that you can feed into the identifying, assessing, planning and implementing cycle.

Identify

I suggest that you break identification into two steps:

- Identify the context within which you're looking for risks. Think about the context of the programme, for example, its objectives and scope, any assumptions, stakeholders and the environment in which you're working.

If you're carrying out risk identification within part of the programme, you want to examine in detail the context of that part of the programme. When you understand the context, you can move onto the second step.

- Identify individual risks. State them in a clear and unambiguous way.

Assess

Having identified a set of risks, the next step is to assess them. You need to estimate each threat and opportunity. For each risk look at the probability, the impact and, if appropriate, the proximity.

Earlier in the ‘Getting risk clear: Basic phraseology’ section, I show you a Summary Risk Profile and suggest that behind it you need clear standards, which help everyone estimate probability and impact in a consistent way.

After you decide the magnitude of a series of risks, you can then evaluate the net aggregated effect of the risks:

- Plot the risks onto a Summary Risk Profile so that you can simply look at the profile and judge the aggregated effect.

- Add up the financial effect (expected value) of the risks, if they can be expressed in financial terms. This total is the expected monetary value.

Plan

So for each risk that you decide you need to deal with, prepare a specific management response to remove or reduce the threat or maximise the opportunity. The aim is to make sure that the programme isn't taken by surprise.

Implement

Your goal is to make sure that the risk-management actions are implemented and then monitored to ensure that they're having the effect you anticipate; that way, you can take corrective action if necessary.

When you implement risk-management actions, you're entering into an execution, monitoring, controlling and scanning cycle that can go on for a long time. That cycle may happen as part of the implement step or it may trigger re-identification of risks: the next step in the process.

Embed and review

Risk management is cultural: people have to want to do it. In the embedding and reviewing process you can ensure that risk management is used appropriately and that risks are successfully handled. Carry out some form of health check on your risk management (a questionnaire that asks if you have all the different bits of risk management in place) or perhaps even a risk management maturity review (a more sophisticated assessment that looks at how repeatable each of the elements of risk management within your organization is).

The important thing about both of these techniques is that after you've assessed where you are, if you're not happy with the situation you get some pointers on what actions you can take to improve your risk management.

Another element of embedding and reviewing is to make sure that you're looking at the post-action risk magnitude (the residual risk) and feeding that back into risk assessment to see whether you need to take more actions.

Therefore, embedding and reviewing can take place at several levels from the detail of individual risks to the overall effectiveness of your risk-management cycle.

Responding to risks

You can use several types of risk response as part of the risk-management process. You may have the same or difference response types for threats and opportunities. I look first at the threat responses:

- Avoid a risk. You decide that you must remove completely the cause of the risk. You can avoid all the risks in a programme if you stop the programme. The avoid response is the most dramatic response and so you rarely use it. After all, you can avoid getting hit on the head by falling blue ice from an aeroplane, but do you want to spend the rest of your life indoors?

- Reduce the risk. You take action now to change the probability or the impact of the risk. This is one of the most common mitigation actions.

- Transfer the risk to a third party. For example, you take out insurance.

- Share the risk with multiple parties. For instance, in the supply chain. A common example is a contract with shared profit or shared pain and gain.

- Accept the risk. You say, ‘All right, there's a risk but the cost of mitigation would be greater than the cost of the risk factored by its probability’. So you simply live with the risk and take the chance.

- Prepare contingency plans. You prepare plans now that make taking action later easier. In other words, you prepare a plan that reduces the impact of the risk after it has happened.

I regard contingency plans as being one of the poorer ways of dealing with risks. I reserve them for high impact, low probability risks.

I regard contingency plans as being one of the poorer ways of dealing with risks. I reserve them for high impact, low probability risks.The great value of risk management is that it enables you to look into the future and modify what's going to happen; in other words, to mitigate the risk. Contingency planning doesn't really mitigate the risk. Agreeing a contingency plan doesn't have any effect on the probability, it just slightly reduces the impact after the event. The only circumstances in which using a contingency plan makes sense is when the probability is already low, but the very large impact makes it necessary to do something. For lots of high impact risks, a better approach is to reduce that high impact, which brings down the overall size of the risk.

Here are a couple of risk responses that apply only to opportunities:

- Exploit the risk. You implement the risk that you've seen. You make the risk happen. If I advertise this training course, we get more delegates. So I exploit the risk by buying advertising for that course.

- Enhance the risk. You may be able to take the same action in several different places, so that multiple opportunities come to fruition. If exploiting the risk works once, then I can enhance it by taking out advertising for every course I'm going to deliver. (If you think of risks as being negative, try replacing the word risk with opportunity in the last couple of paragraphs and it makes a bit more sense.)

Table 11-1 provides a quick overview of the response options that apply to threats and opportunities.

Table 11-1 Generic Risk Response Options

|

Threat |

Opportunity |

Explanation |

|

Avoid |

Exploit |

Remove the risk by removing/implementing the cause. |

|

Reduce |

Enhance |

Action now to change the probability or impact. |

|

Transfer |

|

Pass part of the risk to a third party (an insurer?). |

|

Share |

|

Multiple parties (supply chain) share pain/gain. |

|

Accept |

|

Take the chance. |

|

Prepare contingency plans |

|

Prepare plans now to take action later. |

At the top of the figureI include the format of the very simple language that I find is best used when writing about risks. I like to use the ‘if x then y’ phrasing (such as, ‘If I write this paragraph incorrectly then I have to redraft it’), because it forces you to write down both an event (which has a probability) and an effect (which has an impact). To discover more about the importance of using precise language, take a look at the nearby sidebar ‘

At the top of the figureI include the format of the very simple language that I find is best used when writing about risks. I like to use the ‘if x then y’ phrasing (such as, ‘If I write this paragraph incorrectly then I have to redraft it’), because it forces you to write down both an event (which has a probability) and an effect (which has an impact). To discover more about the importance of using precise language, take a look at the nearby sidebar ‘