Chapter 15

Getting Started with Benefits Management: Modelling the Benefits

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding the central role of benefits in a programme

Understanding the central role of benefits in a programme

![]() Discussing the importance of benefits management

Discussing the importance of benefits management

![]() Identifying and describing your benefits

Identifying and describing your benefits

![]() Documenting your approach to benefits management

Documenting your approach to benefits management

Programme benefits ‒ how you measure the achievement of outcomes ‒ are what a transformational change programme is all about. As I discuss in this chapter, you have a wide range of modelling techniques available to help you create a sensible map of the benefits to be achieved in your programme; additionally, you can document these benefits in a variety of ways.

Benefits management is an important subject to which I devote two chapters. In this one I describe the concepts behind benefits, including some key definitions and useful documentation as well as several figures that help put benefits into context. I also discuss how to identify, test, map, categorise and model benefits, useful tasks that I suggest you undertake in a benefits management workshop. I cover the benefits life-cycle in Chapter 16.

Considering the Concept Behind Benefits

In this section I look at the rationale for benefits, and I take this important subject nice and slowly: you encounter some extremely useful ideas here.

Placing benefits front and centre

The trigger for any change initiative needs to be the desire to realize benefits, some value if you like. I'm using the term change initiative at the moment, because at the very early stages you may not know whether the initiative is going to be a project or programme.

Consider re-reading the above paragraph because it contains some important ideas: in particular, I want you to get really comfortable with the idea that you do change in order to achieve benefits. Think of some changes you've been involved in, what the benefits were and whether they were properly managed.

If the organization does want to manage benefits and projects within the same initiative, you probably want to take an outcome-driven approach to planning. If the main focus is on achieving change, then only a benefits- or outcomes-related view can help you understand and manage change.

Of course, some people stick resolutely to a project view of the world. They think that a project builds things and exploitation is someone else's responsibility. If that's the case, you aren't going to be able to deploy all your programme management: sometimes the organization's culture is just too strong. But I assume in this chapter that the culture accepts a co-ordinated project-delivery and benefit-realization approach and therefore look at what that means.

- Benefits are the trigger for an initiative.

- You realize benefits through change ‒ they're the fundamental reason for a programme.

- Change results in outcomes.

- Benefits are quantifications of (that is, they measure) outcomes.

If you can understand each of those bullet points then you've got it; you understand the central role of benefits in achieving change. In essence, programmes are about co-ordinating delivery from a set of projects and integrating with that capability delivery (the realization of a set of benefits).

- The programme is driven by benefits: no benefits, no programme.

- Modelled benefits are a key input to the Business Case: its performance improvements justify the investment.

Defining benefits

You know what a benefit is, right? Well, I just want to be clear with a precise definition.

For example, if you look at a dis-benefit (a decline resulting from an outcome; see the later section ‘Discovering the dark side: Dis-benefits’), perhaps reduced staff morale, some may argue that this isn't connected to an organizational objective. However, it's really dangerous to ignore the effect of a transformational change on staff morale.

A good organization has an organizational objective of maintaining staff morale. Therefore, a drop in staff morale is relevant to an organizational objective, and so can be counted as a benefit or dis-benefit.

- Output:

- A tangible or intangible artefact

- Produced, constructed or created as a result of a planned activity

- Capability:

Managing Programme Benefits

As I describe in this section, benefits management is the identification, definition, tracking, realization and optimisation of benefits within and beyond a programme.

Accelerating the programme: Benefits management as the driver

Benefits management sits at the heart of programme management and drives many (indeed most) aspects of the programme, including the following:

- Aligning and validating the Blueprint and projects

- Comparing with costs to test viability

- Prioritising to maximise value

- Planning the programme

- Engaging stakeholders

- Defining fit-for-purpose capability

- Informing tranche reviews

- Balancing costs and value

- Monitoring risks and issues

If the programme needs active benefits management, that management needs to include:

- Identifying of benefits

- Baselining of benefits

- Measuring of benefits

In essence, these points reflect the standard management activities, applied to benefits.

Identifying the areas of focus of benefits management

When you adopt benefits management, the focus is on enabling benefits realization and not just delivery of capability: it runs all the way from identification of the benefits through to their measurement and is continuous. It even goes beyond the end of the programme. In the Benefits Management Strategy (which I cover later in ‘Deciding on your strategy for managing benefits’), you record when the programme stops counting benefits and responsibility transfers across to business as usual.

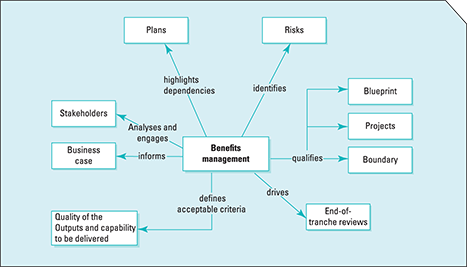

Figure 15-1 provides an illustration of the interfaces between benefits management and other aspects of programme management, as follows:

- Plans. Benefits can highlight dependencies that need to be reflected in the plans.

- Risks. Looking at benefits helps you to identify risks.

- Blueprint. Benefits qualify the Blueprint. The outcomes in the Blueprint have to be measurable by benefits.

- Business Case. Benefits, along with costs, inform the Business Case, allowing you to test the on-going viability of the programme. Costs must be balanced against benefits. They help the programme make trade-offs to achieve maximum value.

- Quality. Quality criteria are ultimately defined by benefits. Fitness for purpose can be considered as fitness for benefits.

- Stakeholders. Benefits sit within stakeholders’ areas of interest. They're a great aid to engagement.

- End-of-tranche reviews. Benefits drive these reviews. If benefits aren't being realized, the programme has to change direction.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 15-1: Benefits management interfaces.

Naturally, benefits management helps ensure that benefits are indeed managed and that the programme is aligned to the transformational flow, because one of the key processes within the flow is Realizing the Benefits (flip to Chapter 20 for more on realizing benefits).

Aligning with corporate strategy

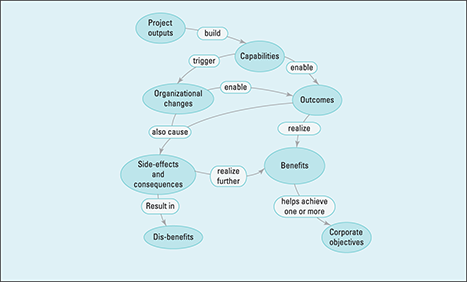

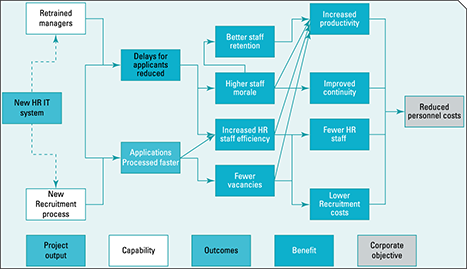

Benefits management can help ensure that the programme is aligned with corporate strategy. Figure 15-2 depicts the relationships between outputs, capabilities, outcomes, benefits and corporate objectives:

- Capabilities. Outputs is a term used in the project world: people working in projects see them as the end of the project. When you think of those outputs from the business-as-usual perspective, you can see that they aren't the end ‒ they're the beginning. They're capabilities that can be used to achieve outcomes and benefits. Outputs are usually grouped into capabilities: although not a hard and fast rule, in general I think of outputs as being at a lower level of detail than capabilities.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 15-2: Path to benefits realization and corporate objectives.

- Outcomes. One of the most common phrases when considering transformational change programmes is that ‘capabilities are exploited in order to achieve outcomes’ (remember that outcomes are the effect of change). They're visible in the real world, what happens when you, to put it very simply, use capabilities.

- Benefits. How you measure outcomes. I don't mean as simple as one benefit being the measure of a single outcome, though: you have a many-to-many relationship between benefits and outcomes. When you understand these relationships, the benefits give a picture of your progress towards achieving the outcomes.

- Corporate objectives. From a programme you can't dictate the format of corporate objectives: the organization decides how it wants to state these. But benefits almost certainly feed into the breakdown of corporate objectives or key performance indicators (see the later sidebar ‘Benefits and key performance indicators’): those outcomes and benefits are what enable you to achieve transformational corporate objectives.

- Organizational changes. You can take a slightly more nuanced view of what's needed on the journey from capabilities to outcomes. Almost certainly you have to make some detailed changes in business as usual in order to enable outcomes. That mixture of capabilities and organizational changes, in the real world, is what leads to the outcomes.

- Side effects and consequences. Organizational changes and outcomes are likely to have side effects that weren't your primary intention. For example, if you aim to get more business via your website, you may find that you get less business in your high-street shop. As well as side effects, you also have to deal with consequences (knock-on effects). For example, if business goes down in your shop, you may find that your reputation suffers.

- Dis-benefits. If you're very lucky the side effects and consequences give rise to further benefits, but also recognise that they may lead to dis-benefits. As I say in the next section, you need to manage dis-benefits.

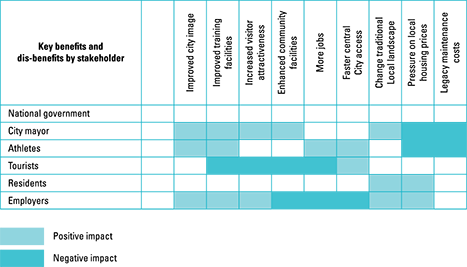

Discovering the dark side: Dis-benefits

In the simple world of a project, you can sometimes imagine that everyone is pleased to have the output and that all users are happy. In the complex world of the programme, however, you're dealing with a more diverse set of stakeholders, some of whom welcome the change and others who're unhappy with it. Consequently, you need to recognise the existence of dis-benefits within a programme.

If you simply ignore dis-benefits, they go unmanaged and surprise you (probably unpleasantly) in the future. You can't predict and manage the effect of the dis-benefits, so you have to model and manage them just as rigorously as you manage benefits.

That said, you may not identify all the dis-benefits at the beginning of the programme. Just as with side effects and consequences, often partway through a programme you become aware of additional dis-benefits. Therefore you need to revisit your benefits model and properly plot new dis-benefits and manage them.

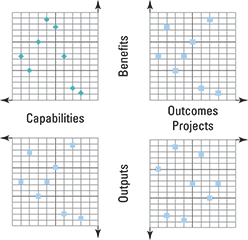

Figure 15-3: Many-to-many relationships in a programme.

Looking at the big benefits picture

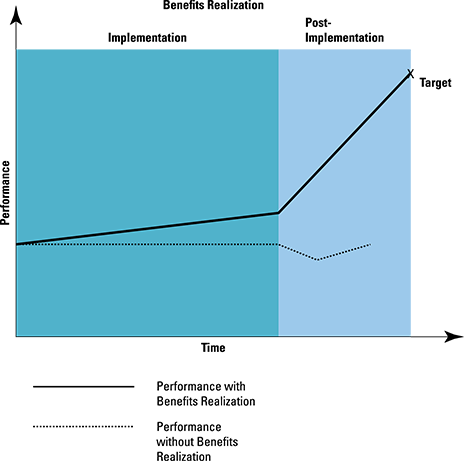

The preceding sections include a number of new ideas around benefits management, so perhaps your head is spinning. If so, I provide Figure 15-4 to help sort things out.

Here's how the figure works:

- Dotted line: Shows what used to happen when you simply delivered a project: nothing until the end of the project ‒ no performance improvement and no benefits while the output was being developed. The output was handed over to the user community (to business as usual). Perhaps you didn't have adequate communication between the project and business as usual, or perhaps even experienced a drop in performance after delivery of the output (sometimes called a learning dip).

Only after a significant amount of effort in business as usual (possibly unplanned effort) did performance return to the original level. And only then did benefits start to be realized.

- Thick line (your goal): To have a smooth increase in performance (realization of benefits) after the output or capabilities are delivered. But also the hope that initial benefits can be realized in anticipation of the delivery of capabilities (which can be called quick wins).

You may say that this situation is getting something for nothing ‒ and you'd be right! It certainly requires considerable communication and trust between the business and project communities, which is the whole reason why you set up a programme organization.

Figure 15-4: Benefits realization.

Imagine you wind down a facility to maintain outdated equipment in anticipation of the delivery of replacement equipment. The staff that you used to maintain the old equipment can be redeployed, which is a benefit and occurs before you have the new equipment. But you have to be pretty certain that the new equipment is going to arrive on schedule.

Being Clear about Each Benefit: Your Benefits Identification Workshop

In Defining a Programme, a process I cover in Chapter 7, you model the benefits. At the heart of that is a benefits workshop, benefits modelling workshop or benefits identification workshop. Don't get too hung up on the precise name for your workshop, the key is to choose a name that makes your stakeholders comfortable. Here are some of the techniques to use. The sequence in your benefits workshop is to:

- Brainstorm benefits and check that they're measurable.

- Apply the critical tests to the benefits.

- Categorise the benefits using one of the many available categorisation criteria.

- Plot the benefits onto a map.

- Document the benefits.

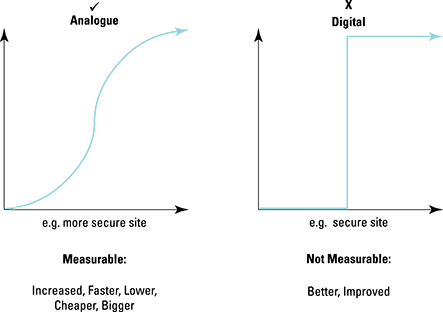

You can think about benefits as being analogue or digital (see Figure 15-5):

- Analogue benefits: Vary continuously across a range of values. The example I take is of a more secure site (Internet site or a physical location; it doesn't matter for this example). When you talk about ‘a more secure site’, you can discuss the number of breaches that happen over time.

- Digital benefits: A less useful description, because a digital (binary) description can have only values of zero or one, yes or no. If you simply say you want ‘a secure site’, you're defining a digital benefit. A site is secure until a breach occurs, at which point it's no longer secure: measuring, managing or monitoring the benefits doesn't help you.

Figure 15-5: Progressive measurable benefits.

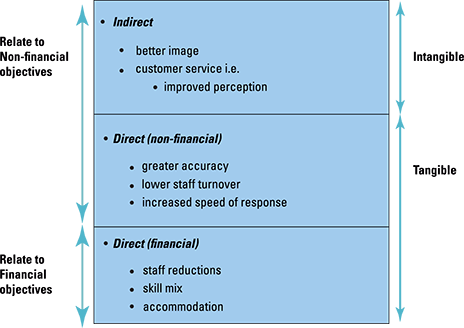

In this section I give you a whole range of different ways in which you can categorise benefits: some are straightforward, others are more sophisticated. I find some very useful (my favourite is to split benefits into direct financial, direct non-financial and indirect categories) and others just too clever by half (for example, the precise definitions of cashable and non-cashable benefits). Your task in your programme is to choose one or more ways of categorising your benefits that helps you: an approach that makes benefits management easier, not more complex.

Confirming real benefits: Critical tests

While you're identifying your benefits, you do so by brainstorming possible benefits. The best way to ensure that you've identified a real benefit is to apply critical tests in the following four areas:

- Description of the benefit. Make sure that you're describing something that's a measure of an outcome.

- Observation. Ensure that you can see some difference in the state of the world. If you use highly abstract terms for a benefit, the observation of the benefit just becomes a matter of judgement and may not be very useful.

- Attribution. Examine where the benefit will arise and, more importantly, whether the programme can claim its realization. Quite often several initiatives are running in the same part of the business. When the benefit arises in that part of the business, how much of that benefit can you claim? Knowing where the benefit will arise makes deciding on ownership and the associated change that much easier.

- Measurement. Consider whether the way you're going to measure the benefit is cost-effective and realistic. You don't want benefit measurement that costs more than the benefit is worth! Also some forms of measurement involve asking people questions they're unwilling to answer. If the measurement is too expensive or too intrusive, the benefit isn't achievable.

Categorising benefits

Categories for benefits are useful for two primary reasons:

- To help you identify benefits

- To give an indication of where (or by whom) a particular benefit needs to be managed

Categorisation can help you to:

- Balance benefits and risks

- Enable a portfolio-level view (if all the change initiatives in a portfolio are categorising benefits in the same way then the people up at portfolio level can look at benefits consistently)

- Enable tracking by category

- Identify overlaps where you're using two different ways of describing the same benefit

- Increase understanding through common terminology

- Manage changes of priority

- Track relationships

- Understand impact

Here are several examples of categorisation approaches, in the order in which I discuss them in the following three sections:

- Categorising by measurement mechanism

- Categorising by stakeholder

- Categorising by corporate objectives

- Categorising by value

- Categorising by financial impact

Categorising by measurement mechanism

The trickiest benefits, but the ones that may have the greatest impact on your programme, are those that you can't measure directly: called intangible or indirect benefits.

You can also categorise benefits by stakeholder, as I show in Figure 15-7.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 15-6: Categorising benefits by measurement mechanism.

Figure 15-7: Benefits distribution matrix of stakeholders.

Tying benefits to corporate objectives

Here are some typical corporate objectives to which you can link types of change you may be triggering from your programme:

- Increased flexibility. Delivering outcomes that allow an organization to respond to strategic demands without incurring additional expenditure.

- Internal performance improvement. Changes that are internal to the organization, such as improved decision-making or more efficient management processes.

- Enhanced personnel or human resources management. A better-motivated workforce may lead to a number of other benefits, such as more flexibility or increased productivity.

- Policy or legal compliance. These changes enable an organization to fulfil policy objectives or to satisfy legal requirements where the organization has no choice but to comply,

- Process improvements. These are ‘more for the same’ or ‘the same with less’ changes that allow an organization to do the same job with less resource, leading to reduction in costs, or to do more with the same resource.

- Enhanced quality of service. Improvements to services ‒ such as a quicker response to queries or providing information in a way customers prefer ‒ give rise to fewer customer complaints and less costly service failures.

- Reduced costs. Improvements in control and reduction of operating costs.

- Improved revenue generation. Changes that enable increased revenue or the same revenue level in a shorter timeframe, or both.

- Reduced environmental impact. Changes that reduce your carbon footprint or mitigate the environment impact of the organization.

- Risk reduction. Changes that enable an organization to be better prepared for the future, for example, hedging currency risks. They may also relate to public safety or the safety of vulnerable groups.

- Strategic fit. Benefits that contribute to strategic fit or enable the strategic direction through long-term investments or market positioning.

Check out Chapter 16 for more on linking programme benefits to corporate objectives.

Categorising benefits by value

I like to talk of effectiveness as being ‘more for the same’ and efficiency as ‘the same for less’. The UK government went a little bit further and expanded on these two nice simple little terms. It created a value-for-money approach known as FABRIC, the framework for performance information where it defined three types of benefit:

- Economic benefit: Financial improvement, releasing cash, increased income or better use of funds. The precise definition is: an economic measure looks at the cost of acquiring the inputs to the programme.

- Effectiveness: Doing things better or to a higher standard. An effectiveness measure looks at whether the outputs of the programme lead to the desired outcome.

- Efficiency: ‘More for the same or the same with less’. An efficiency measure looks at whether you're getting the maximum output from the inputs that go into the process. For example, how many patients are being treated for a given set of hospital facilities.

Categorising benefits by financial impact

You may find that categorising your benefits by financial impact is helpful. The terms I give you here are much used by the Cabinet Office Efficiency and Reform Group and similar bodies and are particularly relevant in the UK public sector.

Here are the two categories with examples:

- Cashable (benefit can be turned into cash):

- Lower supply chain costs

- Staff savings

- Lower running costs

- Non-cashable (benefit can't be turned into cash):

- Staff time savings

Documenting the Benefits

After you identify your benefits, apply the critical tests and categorise them in a straightforward way, you need to sort out the documentation.

Linking benefits: The Benefits Map

Figure 15-8 shows a Benefits Map with different types of artefact: outputs, capabilities, outcomes, benefits and corporate objectives. You have to decide how many different types of artefact you want to show on your Map. As so often, the aim is to put on as many things as help you and your colleagues in understanding your programme:

- Project output: A straightforward output from a project.

- Capability: One or more outputs in business as usual, but not yet used, are a capability.

- Outcome: The capability is exploited and triggers change. The effect of that change is an outcome ‒ something you can observe. You can rephrase this as, for example, ‘patients not being delayed’.

- Corporate objective: The benefits contribute to a corporate objective.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 15-8: Benefits Map for a new human resource system.

As well as a Benefits Map you can also have a Benefits Register, which summarises the information in the Benefits Profiles (see the later section ‘Building a Benefits Profile’), thus providing an overview of the programme's benefits.

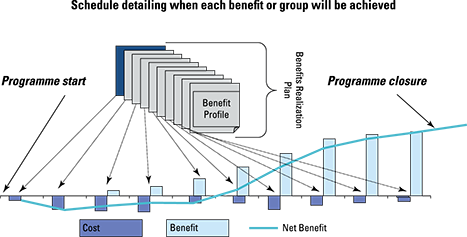

Assembling a Benefits Realization Plan

Remember the very close relationship with stakeholder engagement: benefits are improvements that stakeholders see as advantages.

Figure 15-9 illustrates a Benefits Realization Plan. A real plan is a more complex document, but I hope this one shows how the benefits need to come together into a single co-ordinated plan that includes dates.

You to need to take all the Benefit Profiles, integrate them, remove the anomalies and double counting, and plot the benefits on one or more schedules.

Figure 15-9: A Benefits Realization Plan.

Building a Benefits Profile

You need a benefit profile for each key benefit, that is, for each benefit that you have to describe in order to justify the Business Case. The minimum contents of a Benefits Profile are along the following lines:

- A description of the benefit

- The owner of the benefit

- How the benefit will be tested

But you can add many other headings, too. Quite often the Profile contains a great deal of detail if the benefit is large:

- Identifier

- Benefit description

- Supported objectives

- Category

- Affected key performance indicators

- Baseline performance levels and anticipated improvement

- Costs for realization and change

- Capabilities-required related project

- Precursor outcomes

- Business changes required

- Related issues and risks

- External dependencies

- Responsibilities

- Attribution

- Measurement

Deciding on your strategy for managing benefits

Here are the sorts of things you can cover, in very broad terms:

- Do you want benefits as early as possible ‒ no matter what sort of disruption it causes? Or do you want to minimise organizational disturbance even though that delays the realization of benefits?

- Does some overriding necessity to maintain services while you're putting in place the new world exist?

- What's the situation regarding existing projects? If yours is an emergent programme, you can cover this fact in the Benefits Management Strategy.

- What's your approach to early wins? Or to be more precise, to early benefits possibly being delivered even before you have capabilities?

Here's the composition of your Benefits Management Strategy:

- Acceptable measures

- Capabilities and benefits

- Measurement methods

- Priorities

- Responsibilities

- Scope

- Stopping double counting

Benefits occur as a result of change; they don't occur while the status quo is in place. Therefore, I argue that benefits are the fundamental reason for undertaking a programme. Later on when you're defining benefits you have to make sure that you're measuring change, not the status quo. Of course benefits can trigger any initiative, but the real test is whether the organization wants to manage benefits in a structured way, co-ordinated with structured management of projects.

Benefits occur as a result of change; they don't occur while the status quo is in place. Therefore, I argue that benefits are the fundamental reason for undertaking a programme. Later on when you're defining benefits you have to make sure that you're measuring change, not the status quo. Of course benefits can trigger any initiative, but the real test is whether the organization wants to manage benefits in a structured way, co-ordinated with structured management of projects. Here's how I suggest you view the benefits rationale:

Here's how I suggest you view the benefits rationale: A benefit is a measurable improvement resulting from an outcome that one or more stakeholders perceive as an advantage, and contributes to one or more organizational objectives. Notice how subjective this definition is: if something is perceived as an advantage by a stakeholder, any associated measurable improvement can be a benefit.

A benefit is a measurable improvement resulting from an outcome that one or more stakeholders perceive as an advantage, and contributes to one or more organizational objectives. Notice how subjective this definition is: if something is perceived as an advantage by a stakeholder, any associated measurable improvement can be a benefit. You limit benefits to measurable improvements that contribute toward one or more organizational objectives, which some people may consider quite a contentious statement. This limitation suggests that some outcomes, perceived to be important by stakeholders, can be ignored because they can't be linked to an objective. My advice is simple. Don't ignore benefits that stakeholders are passionate about just because you can't see a link to organizational benefits.

You limit benefits to measurable improvements that contribute toward one or more organizational objectives, which some people may consider quite a contentious statement. This limitation suggests that some outcomes, perceived to be important by stakeholders, can be ignored because they can't be linked to an objective. My advice is simple. Don't ignore benefits that stakeholders are passionate about just because you can't see a link to organizational benefits.