Chapter 17

Leading People Through Change as the Programme Delivers

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding the difference between leadership and management

Understanding the difference between leadership and management

![]() Designing tranches to support transition

Designing tranches to support transition

When you start to exploit the capabilities delivered by projects, you need to do some mechanistic work, which in essence is based around controlling against a plan. For example, part of benefits management is creating a model and then managing against that plan. But a fundamental difference in tone exists in the real world of business as usual, which is less ordered and less planned than a mechanistic world and much more about people, as individuals and in teams, than about the task.

Hence my focus in this chapter is clear and effective leadership, which is essential for a successful programme. When the projects have delivered a capability, the transition really begins to take place. Leading people through change is so important that I dedicate this whole chapter to it. I look at the nature of leadership and the effect it has on how you fulfil any of the different roles. I also describe transition and give you a better appreciation of what's involved by thinking about the more people-focused aspects of programme management.

Taking a Deep Look at Leadership

Just how important leadership is in your programme depends on the programme's nature:

- If your programme is essentially a complex specification-driven set of projects, you may need little more leadership than is required in any project.

- If your programme is transformational and includes culture change (in other words, you're trying to persuade people to behave in fundamentally different ways), leadership clearly becomes more significant.

Distinguishing leadership from management

Table 17-1 Comparing Leadership and Management in Programme Management

|

Leadership |

Management |

|

Particularly required in a context of change. It clarifies the ‘as is’ and the vision of the future and thrives in the tension between the two. |

Always required, particularly in business-as-usual contexts, and focuses more on evolutionary or continual improvement. |

|

Inclined to clarify the ‘what’ and the ‘why’. |

Directed towards the ‘how’ and the ‘when’. |

|

More concerned with direction, effectiveness and purpose. |

Concerned with speed, efficiency and quality. |

|

Most effective when influencing people by communicating in face-to-face situations. |

Most effective when controlling tasks against specifications or plans. |

|

Focused on meaning, purpose and realized value. |

Focused on tasks, delivery and process. |

Examining the leaders’ requirements

Programmes are different from business as usual (because you're using a completely different set of roles), and therefore these roles need to be clearly defined. The roles may not be familiar to the people working in the programme, so the responsibilities also need to be defined clearly.

Similarly you need to put in place a whole range of management structures and reporting arrangements to govern your programme. You need to create and communicate them, of course, but because they're new ways of working leadership is required as you introduce them.

These different characteristics of a programme place different requirements on the leaders:

- Information needs to flow in different ways to allow programme leaders to make their decisions. The flow of information needs to be more open and faster; plus the information needs to be better. It can mean more appropriate, relevant, timely, or less information, or different information, or presented in a different way. In your programme you can see if the information is presented in the right way just by looking at the faces of the people who read your reports.

Better information isn't just more information: the danger of information overload is ever present.

Better information isn't just more information: the danger of information overload is ever present. - The top team in a programme changes over its life. That team needs to have a balanced set of skills for the work being done by the programme in a particular tranche, and therefore the requirement of the leaders in the programme is for them to lead that balanced team.

- More informed decision making also requires a more open culture than is common in many business-as-usual environments. The world is changing rapidly: you have to talk to different people and you have to lead in a constantly changing environment.

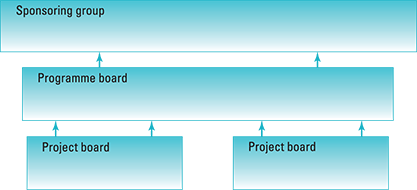

Looking at the three levels of governance

The rapidly changing governance landscape can be pretty confusing, and so stepping back and identifying the three levels of governance is helpful. I summarise these levels in Figure 17-1 and in the following list. I also include the relevant roles for each of these different levels of governance:

- Direction: Strategic guidance and championing:

- Carried out by the Sponsoring Group and the Senior Responsible Owner (SRO).

- Management: Execution of capability delivery and exploitation:

- Carried out by the Programme and Business Change Managers.

- Co-ordination: Of information, communication, monitoring and control:

- Carried out by the Programme Office.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 17-1: Layering of programme direction, management and co-ordination.

I often see the Programme Office, which is designed to and works very effectively as a co-ordination function, accidentally taking on managerial responsibilities. If that's the way you design your organizational structure, that's absolutely fine; but my advice is to think carefully about these levels of governance as you design your organization structure.

Enjoying effective leadership

Helping an organization move through transformational change requires more than management: it needs leadership. But the word leadership is used so often that you can lose sight of what it means.

Here are a few of my thoughts. Those leading the programme need to:

- Create a compelling Vision of the beneficial future as a result of carrying out the programme. They must communicate this future in an inspirational way to a wide range of stakeholders.

- Give individuals give the freedom and autonomy to fulfil their roles effectively. Motivation, reward and appraisal systems can play a role in fostering the attitudes and energy to drive the programme.

- Commit visibly with authority and enough seniority necessary to:

- Ensure that the correct resources are available to influence and engage with stakeholders.

- Balance the priorities of the programme with those of on-going business operations.

- Focus on the realization of business benefits.

- Ensure the active management of:

- Cultural and people issues involved in the change.

- Finance and the inevitable conflicting demands on resources.

- Co-ordination of projects within the programme to see through transition to new operational services while also, crucially, maintaining business operations.

- Risk management: that is, identification, evaluation and mitigation of risks.

Without doubt, plenty of scope exists for effective leadership in a programme!

Considering Sponsoring Group behaviour

Talking about leadership in an abstract way is all fine and dandy, but what about the crucial area where leadership needs to be displayed: the behaviour of the Sponsoring Group.

The Sponsoring Group doesn't have an onerous set of responsibilities to exercise in a programme, but its behaviour has to provide the necessary leadership for the programme.

To put it bluntly: the Sponsoring Group has to walk the talk.

- Provides executive-level commitment

- Contains the senior managers responsible for investment

- Leads in establishing values and behaviours

- Works more as a group as normal reporting lines may not apply (usually each member of the Sponsoring Group runs their own bit of the business. In a programme they let their people (Business Change Managers) report to a different member of the Sponsoring Group (the SRO); this is what triggers the need for more group working)

- Forms the overarching authority

- Displays a different leadership style:

- More team working

- Greater empowerment

- Encouraging initiative

- Recognising appropriate risk taking

Establishing the Sponsoring Group's duties

In some business cultures the Sponsoring Group is too senior to have formal terms of reference. Nevertheless, it still needs to exercise some key responsibilities, which may have to be done quite formally. The Sponsoring Group can display leadership while doing these tasks, which include:

- Providing a context for the programme (not just initially, but on an on-going basis).

- Authorising the programme Mandate.

- Authorising programme definition.

- Participating in end-of-tranche reviews and approving progression to the next tranche for the programme.

- Authorising funding for the programme.

- Resolving strategic and directional issues between programmes that need the input of an agreement from very senior stakeholders to ensure the progress of the change.

- Authorising the organization's strategic direction against which the programme is to deliver.

- Authorising the progress of the programme against the strategic objectives and then moving from the mechanistic (where you write things down and expect people to carry out the plan) into the behavioural area (where you look at and modify what people actually do), leading by example to implement the values implied by the transformational change.

- Providing continued commitment and endorsement in support of the programme: for example, reiterating the programme objectives at executive or communications events.

- Appointing, advising and supporting the SRO.

- Authorising the Vision statement.

- Authorising delivery and sign off at the close of the programme.

Although this list seems rather long, it's mostly about authorisation, so the decisions needn't take up a lot of the Sponsoring Group's time.

Tackling Transition in a Tranche

The main purpose of this section is to look at some of the softer considerations during transition within a tranche. But it's also a useful opportunity to think about some of the technical aspects to consider when designing and planning a tranche. The biggest need for leadership is in tranches, as business as usual changes its way of behaving.

For loads more on planning and managing tranches, check out Chapters 10 and 18, respectively.

Handling design planning

The business has to remain viable as you roll out successive tranches into business as usual. Consequently, as part of effective leadership you need to consider the design of the business during each tranche.

As you introduce new elements of ‘to be’, you may want to decommission redundant parts of ‘as is’. But often two different parts of the business rely on the same back-office function. As one part of the business migrates to a new state, you can be tempted to switch off that old back-office function. But you may have to maintain it in some form until all the other elements of the business that rely on it have migrated.

This advice sounds like common sense, but it's easily overlooked in the excitement of building the brave new world.

You may need to consider aspects such as:

- Technical architecture:

- Different technical environments

- Office and homeworking environments

- Support infrastructure:

- Accounting procedures

- Human resource needs

Managing transition

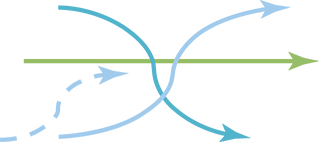

After establishing a design authority to look after the detailed technical design you're creating in a tranche, you need to engage with the Business Change Managers and think about the transition management they'll be doing. Figure 17-2 is a diagram I like to draw when explaining the complexity of transition management.

Figure 17-2: Overview of transition management.

Figure 17-2 summarises the role of the Business Change Managers while they're introducing the new state. Here's what they need to do:

- Build up the new – the rising arrow. Think of it simplistically as a new production line going from producing zero widgets per day to 1,000 widgets per day.

- Run down the old – the falling arrow. At the same time, the old production line has to run down from producing, say, 500 widgets to producing none.

- Maintain business as usual – the level arrow. You have to handle the balancing act, because you have to maintain business as usual. You still have to keep widgets going out to customers.

- Prepare properly for the new before you receive any outputs – the dotted arrow. You need to consider lots of things to do this effectively: staff training and recruitment, accommodation, procedures and the detailed plans for ramping up and ramping down.

Following the transition sequence

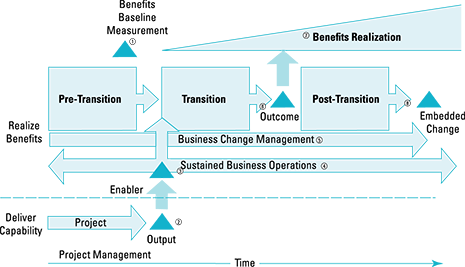

Here I look in detail at transition, the sequence involved and the relationships between outputs, transition management and benefits realization. This is the detail of the change occurring.

If Figure 17-2 in the preceding section looks a little simple, you may find Figure 17-3 a little too complex, which is why I take you through it in this section (I provide a fuller, step-by-step approach in Chapter 20):

- Baseline benefits measurement. Pre-transition is about the Business Change Managers preparing for the receipt of outputs by producing plans. You also have to create a baseline benefits measurement. Before business as usual is disturbed, you need to measure the baseline values of benefits. Each benefit owner does this by using the measurement mechanism described in the Benefit Profile.

- Project output. The project delivers outputs that are fit for purpose. Within business as usual, these outputs or groups of outputs are considered to be enablers or to have a capability.

- Sustained business operations. Capabilities are exploited in business as usual in order to achieve sustained business operations. If you like, that's what transition is all about.

- Business Change Management. The Business Change Managers monitor and control this transition, helping to manage the change.

- Outcomes. Over time the effect of change becomes noticeable, and you see the outcomes.

- Benefits realization. All the while benefits are accumulating that you measure. The cost of production decreases, for example, and you use those measures or benefits to monitor transition.

- Post-transition activities. You embed the change into business as usual, remove old facilities, equipment and ways of working, and get everyone settled into the new way of working – the ‘to be’ state.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2011 Reproduced under licence from AXELOS

Figure 17-3: Outputs, transition management and benefits realization.

Before reading this section, have a go at noting down your ideas on the differences between leadership and management. Of course, no single set of right answers exists, but you can check your notes against my thoughts in Table

Before reading this section, have a go at noting down your ideas on the differences between leadership and management. Of course, no single set of right answers exists, but you can check your notes against my thoughts in Table  Be particularly careful with management and co-ordination. The Programme Office works for the Programme Manager. As the Programme Manager's role gets bigger, that person appoints specialists to carry out part of the duties. For example, a Programme Manager may appoint someone to handle risk: but is that person a Risk Manager or a Risk Co-ordinator? A co-ordination function sits in the Programme Office, but if it's a managerial function, the person in the role is managing. Managers are responsible for making it happen. But it's unlikely that a risk ‘manager’ manages either individual risks or executing the risk process. My advice is to have fewer managers and more co-ordinators.

Be particularly careful with management and co-ordination. The Programme Office works for the Programme Manager. As the Programme Manager's role gets bigger, that person appoints specialists to carry out part of the duties. For example, a Programme Manager may appoint someone to handle risk: but is that person a Risk Manager or a Risk Co-ordinator? A co-ordination function sits in the Programme Office, but if it's a managerial function, the person in the role is managing. Managers are responsible for making it happen. But it's unlikely that a risk ‘manager’ manages either individual risks or executing the risk process. My advice is to have fewer managers and more co-ordinators. You can expand each of these points into a major discussion on the behaviours that reinforce these aspects of leadership. I leave you to have those conversations in your programme.

You can expand each of these points into a major discussion on the behaviours that reinforce these aspects of leadership. I leave you to have those conversations in your programme. A tranche is a step change in organizational capability with an associated distinct set of benefits. Projects may run across tranche boundaries, or to put it another way, several tranches may be running in parallel. But if the tranche boundary is a reasonably significant milestone in your programme, it's an ideal opportunity to assess achievements to date and consider any necessary realignment of the programme.

A tranche is a step change in organizational capability with an associated distinct set of benefits. Projects may run across tranche boundaries, or to put it another way, several tranches may be running in parallel. But if the tranche boundary is a reasonably significant milestone in your programme, it's an ideal opportunity to assess achievements to date and consider any necessary realignment of the programme.