Chapter 9

Displaying Performance against a Target

In This Chapter

![]() Using variance displays

Using variance displays

![]() Using progress bars

Using progress bars

![]() Creating bullet graphs

Creating bullet graphs

![]() Showing performance against a range

Showing performance against a range

Hopefully, this is an easy one to grasp. Someone sets a target, and someone else tries to reach that target. The target can be anything from a certain amount of revenue to a number of boxes shipped or to phone calls made. The business world is full of targets and goals. Your job is to find effective ways to represent performance against those targets.

What do I mean by performance against a target? Imagine that your goal is to break the land speed record, which is now 763 miles per hour. That makes the target 764 miles per hour, which will break the record. After you jump into your car and go as fast as you can, you will have a final speed. That number is your performance against the target.

In this chapter, I explore some new and interesting ways to create components that show performance against a target.

Showing Performance with Variances

The standard way to display performance against a target is to plot the target and then plot the performance. This is usually done with a line chart or a combination chart, such as the one shown in Figure 9-1.

Figure 9-1: A typical chart showing performance against a target.

Although this chart allows you to visually pick the points where performance exceeded or fell below targets, it gives you a rather one-dimensional view and provides minimal information. Even if this chart offered labels that showed the actual percent of sales revenue versus target, you’d still get only a mildly informative view.

A more effective and informative way to display performance against a target is to plot the variances between the target and the performance. Figure 9-2 shows the same performance data you see in Figure 9-1 but includes the variances (sales revenue minus target) under the month label. This way, you see where performance exceeded or fell below targets, but you also get an extra layer of information showing the dollar impact of each rise and fall.

Figure 9-2: Consider using variances to plot performance against a target.

Showing Performance against Organizational Trends

The target you use to measure performance doesn’t necessarily have to be set by management or organizational policy. In fact, some of the things you measure may never have a formal target or goal set for them. In situations in which you don’t have a target to measure against, it’s often helpful to measure performance against some organizational statistic.

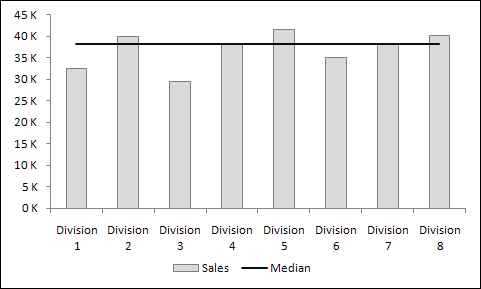

For example, the component in Figure 9-3 measures the sales performance for each division against the median sales for all the divisions. You can see that divisions 1, 3, and 6 fall well below the median for the group.

Figure 9-3: Measuring data when there’s no target for a measure.

Here’s how you’d create a median line similar to the one you see in Figure 9-3:

-

Start a new column next to your data and type the simple MEDIAN formula, as shown in Figure 9-4.

Note that this formula can be any mathematical or statistical operation that works for the data you’re representing. Just make sure that the values returned are the same for the entire column. This gives you a straight line.

-

Copy the formula down to fill the table.

Again, all numbers in the newly created column should be the same.

- Plot the table into a column chart.

- Right-click the Median data series and choose Change Series Chart Type from the menu that appears.

- Change the chart type to a line chart.

Figure 9-4: Start a new column and enter a formula.

Using a Thermometer-Style Chart

A thermometer-style chart offers a unique way to view performance against a goal. As the name implies, the data points shown in this type of chart resemble a thermometer. Each performance value and its corresponding target are stacked on top of one another, giving an appearance similar to that of mercury rising in a thermometer. In Figure 9-5, you see an example of a thermometer-style chart.

Figure 9-5: Thermo-meter-style charts offer a unique way to show performance against a goal.

To create this type of chart, follow these steps:

- Starting with a table that contains revenue and target data, plot the data into a new column chart.

- Right-click the Revenue data series and choose Format Data Series from the menu that appears.

- In the Format Data Series dialog box, select Secondary Axis.

-

Go back to the chart and delete the new vertical axis that was added.

It’s the vertical axis to the right of the chart.

- Right-click the Target series and choose Format Data Series.

- In the dialog box, adjust the Gap Width property so that the Target series is slightly wider than the Revenue series — between 45% and 55% is typically fine.

Using a Bullet Graph

A bullet graph is a type of column/bar graph developed by visualization expert Stephen Few to serve as a replacement for dashboard gauges and meters. He developed bullet graphs to allow you to clearly display multiple layers of information without occupying a lot of space on a dashboard. A bullet graph, as shown in Figure 9-6, contains a single performance measure (such as YTD [year-to-date] revenue), compares that measure with a target, and displays it in the context of qualitative ranges, such as Poor, Fair, Good, and Very Good.

Figure 9-6: Bullet graphs display multiple perspectives in an incredibly compact space.

Figure 9-7 breaks down the three main parts of a bullet graph. The single bar represents the performance measure. The horizontal marker represents the comparative measure. The background color banding represents the qualitative ranges.

Figure 9-7: The parts of a bullet graph.

Creating a bullet graph

Creating a bullet graph in Excel involves quite a few steps, but the process isn’t necessarily difficult. Follow these steps to create your first bullet graph:

-

Start with a data table that gives you all the data points you need to create the three main parts of the bullet graph.

Figure 9-8 illustrates what that data table looks like. The first four values in the dataset (Poor, Fair, Good, and Very Good) make up the qualitative range. You don’t have to have four values — you can have as many or as few as you need. In this scenario, you want the qualitative range to span from 0 to 100%. Therefore, the percentages (70%, 15%, 10%, and 5%) must add up to 100%. Again, this can be adjusted to suit your needs. The fifth value in Figure 9-8 (Value) creates the performance bar. The sixth value (Target) makes the target marker.

-

Select the entire table and plot the data on a stacked column chart.

The chart that’s created is initially plotted in the wrong direction.

- To fix the direction, click the chart and select the Switch Row/Column button on the Ribbon, as shown in Figure 9-9.

-

Right-click the Target series and choose Change Series Chart Type from the menu that appears.

Doing so calls up the Change Chart Type dialog box.

-

Use the Change Chart Type dialog box to change the Target series to Line with Markers and to place it on the secondary axis; see Figure 9-10.

After your change is confirmed, the Target series appears on the chart as a single dot.

- Right-click the Target series again and choose Format Data Series to open that dialog box.

- Click Marker to expand the Marker options and then adjust the marker to look like a dash, as shown in Figure 9-11.

- Still in the Format Data Series dialog box, expand the Fill section, and in the Solid Fill property, set the color of the marker to a noticeable color such as red.

- Still in the Format Data Series dialog box, expand the Border section and set the Border to No Line.

-

Go back to your chart and delete the new secondary axis that was added to the right of your chart; see Figure 9-12.

This is an important step to ensure that the scale of the chart is correct for all data points.

- Right-click the Value series and choose Format Data Series from the menu that appears.

- In the Format Data Series dialog box, click Secondary Axis.

- Still in the Format Data Series dialog box, under Series Options, adjust the Gap Width property so that the Value series is slightly narrower than the other columns in the chart — between 205% and 225% is typically okay.

- Still in the Format Data Series dialog box, click the Fill icon (the paint bucket), expand the Fill section, and then select the Solid Fill option to set the color of the Value series to black.

-

All that’s left to do is change the color for each qualitative range to incrementally lighter hues.

At this point, your bullet graph is essentially done! You can apply whatever minor formatting adjustments to the size and shape of the chart to make it look the way you want. Figure 9-13 shows your newly created bullet graph formatted with a legend and horizontal labels.

Figure 9-8: Start with data that contains the main data points of the bullet graph.

Figure 9-9: Switch the orientation of the chart to read from columns.

Figure 9-10: Use the Change Chart Type dialog box to change the Target series to Line with Markers and place it on the secondary axis.

Figure 9-11: Adjust the marker to a dash.

Figure 9-12: Be sure to delete the newly created secondary vertical axis.

Figure 9-13: Your formatted bullet graph.

Adding data to your bullet graph

After you’ve built your chart for the first performance measure, you can use the same chart for any additional measures. Take a look at Figure 9-14.

Figure 9-14: To add more data to your chart, manually expand the chart’s data source range.

As you can see in Figure 9-14, you’ve already created this bullet graph with the first performance measure. Imagine that you add two more measures and want to graph those. Here’s how to do it:

- Click the chart so that the blue outline appears around the original source data.

-

Hover the mouse pointer over the blue dot in the lower-right corner of the blue box.

The cursor turns into an arrow, as shown in Figure 9-14.

-

Click and drag the blue dot to the last column in your expanded dataset.

Figure 9-15 illustrates how the new data points are added without one ounce of extra work!

Figure 9-15: Expanding the data source automatically creates new bullet graphs.

Final thoughts on formatting bullet graphs

Before wrapping up this introduction to bullet graphs, I discuss two final thoughts on formatting:

- Creating qualitative bands

- Creating horizontal bullet graphs

Creating qualitative bands

First, if the qualitative ranges are the same for all performance measures in your bullet graphs, you can format the qualitative range series to have no gaps between them. For instance, Figure 9-16 shows a set of bullet graphs in which the qualitative ranges have been set to 0% Gap Width. This creates the clever effect of qualitative bands.

Figure 9-16: Try setting gap widths to zero to create clean-looking qualitative bands.

Here’s how to do it:

- Right-click any one of the qualitative series and choose Format Data Series from the menu that appears.

- In the Format Series dialog box, adjust the Gap Width property to 0%.

Creating horizontal bullet graphs

For those of you waiting on the section about horizontal bullet graphs, I have good news and bad news. The bad news is that creating a horizontal bullet graph from scratch in Excel is a much more complex endeavor than creating a vertical bullet graph — one that doesn’t warrant the time and effort it takes to create them.

The good news is that there is a clever way to get a horizontal bullet graph from a vertical one — and in three steps, no less. Here’s how you do it:

-

Create a vertical bullet graph.

For how to do this, see the “Creating a bullet graph” section, earlier in this chapter.

- To change the alignment for the axis and other labels on the bullet graph so that they’re rotated 270 degrees, right-click the axis labels, select Format Axis, go to the Alignment settings, and then adjust the Text Direction property to rotate the axis labels as seen in Figure 9-17.

-

Use Excel’s Camera tool to take a picture of the bullet graph.

After you have a picture, you can rotate it to be horizontal. Figure 9-18 illustrates a horizontal bullet graph.

The nifty thing about this trick is that because the picture is taken with the Camera tool, the picture automatically updates when the source table changes.

Figure 9-17: Rotate all labels so that they’re on their sides.

Figure 9-18: A horizontal bullet graph.

Showing Performance against a Target Range

In some businesses, a target isn’t one value — it’s a range of values. That is to say, the goal is to stay within a defined target range. Imagine that you manage a small business selling boxes of meat. Part of your job is to keep the inventory stocked between 25 and 35 boxes in a month. If you have too many boxes of meat, the meat will go bad. If you have too few boxes, you’ll lose money.

To track how well you do at keeping the inventory of meat between 25 and 35 boxes, you need a performance component that displays on-hand boxes against a target range. Figure 9-19 illustrates a component you can build to track performance against a target range. The gray band represents the target range you must stay within each month. The line represents the trend of on-hand meat.

Figure 9-19: You can create a component that plots performance against a target range.

Obviously, the trick to this type of component is to set up the band that represents the target range. Here’s how you do it:

-

Set up a limit table in which you can define and adjust the upper and lower limits of the target range.

Cells B2 and B3 in Figure 9-20 serve as the place to define the limits for the range.

-

Build a chart feeder that’s used to plot the data points for the target range.

This feeder consists of the formulas revealed in cells B8 and B9 in Figure 9-20. The idea is to copy these formulas across all data. The values you see in the Feb, Mar, and Apr columns are the results of these formulas.

-

Add a row for the actual performance values, as shown in Figure 9-21.

These data points create the performance trend line.

- Select the entire chart feeder table and plot the data on a stacked area chart.

-

Right-click the Values series and choose Change Series Chart Type from the menu that appears.

Doing so calls up the Change Chart Type dialog box.

-

Using the Change Chart Type dialog box, change the Values series to a line chart and place it on the secondary axis, as shown in Figure 9-22.

After your change is confirmed, the Values series appears on the chart as a line.

-

Go back to your chart and delete the new vertical axis that was added.

It’s the vertical axis to the right of the chart.

- Right-click the Lower Limit data series and choose Format Data Series from the menu that appears.

- In the Format Data Series dialog, click the Fill icon and then choose the No Fill option under Fill and the No Line option under Border; see Figure 9-23.

- Right-click the Upper Limit series and select Format Data Series.

-

In the Format Series dialog box, adjust the Gap Width property to 0%.

That’s it. All that’s left to do is apply the minor adjustments to colors, labels, and other formatting.

Figure 9-20: Create a chart feeder that contains formulas that define the data points for the target range.

Figure 9-21: Add a row for the performance values.

Figure 9-22: Use the Change Chart Type dialog box to change the Values series to a line chart and place it on the secondary axis.

Figure 9-23: Format the Lower Limit series so that it’s hidden.

Check out

Check out