1

Core Foundation Related to Forensic Accounting and Fraud Examination

Forensic accounting is simply defined as the intersection of accounting and the law. Consider an insurance claim whereby the insured is claiming that a contractor provided inferior work in March 2017 by placing an exposed water pipe in an unheated attic. In the first week of February 2018, during a two-day cold spell when temperatures dropped below freezing, the water pipe burst causing hundreds of thousands of dollars of water damage throughout 70% (4,200 of 6,000 square feet) of the building. Some questions to ponder include:

- Is the contractor liable for the water pipe failure 11 months later?

- What if there was a three-day cold spell in January 2018 and the pipe did not break? Would the contractor still be liable for the cost of damages from a water pipe break in February 2018?

- What if the water damage occurred at a retail establishment that needed to be closed for three months to repair the damage? Further consider that the business is located in “spring break territory” and earns 50% of its annual income (profit) during February, March, and April?

- Should the damages include lost profits?

- Is the extent of the damage (70% of the total square footage) relevant?

- Was there a contract between the contractor and the claimant?

- What parts of the contract might be relevant?

- Was there a warranty, implied or in writing (contractual)?

There are two overarching questions: (1) Is the contractor liable, and (2) If so, for how much? Further, notice that the calculation of damages involves not only dollars but also contractual obligations, down time, and peak dates, as well as extent of damage (relevant nonfinancial issues).

Forensic accounting also considers employment damages arising from unfortunate events such as a work injury, an auto accident where the victim is unable to work, partially disabled, or is no longer alive. Assume that a victim is rear-ended in an auto accident by an insured. Little doubt exists about the liability of the person, who caused the accident, and his insurance company. In such a case, forensic accounting professionals use a variety of financial information—such as W-2s and tax returns—along with relevant nonfinancial data—such as expected future number of years in the workforce and life expectancy—to place a value on the damages to the victim.

As noted in the previous two examples, forensic accounting issues can be complex and require more than basic accounting data.

Now consider the following case.

David Williams, 54, from Fort Worth, Texas, was arrested on October 12, 2017, by FBI special agents on a federal charge of engaging in a scheme to defraud insurance companies by submitting more than $25 million in false and fraudulent claims for medical services.1

According to the criminal complaint affidavit between November 2012 through August 2017, Williams advertised on his website (getfitwithdave.com) that he offered in-home fitness training and therapy through his company, “Kinesiology Specialists.” Williams identified himself as “Dr. Dave” and stated that he served clients in most of Texas, Las Vegas, Denver, Tucson, Seattle, and Orlando. Through his website, Williams told potential clients that he was accepting most health care insurance coverage plans.

In order to bill insurance companies for his services, Williams registered as a health care provider with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. In completing the application, Williams falsely certified that he was a health care provider. Williams enrolled as a health care provider at least nineteen times under different names or variations of his name and his company names and falsely certified that he was a health care provider in each application. Williams would then bill the insurance companies as if he were a medical physician and as if he had provided care requiring medical decision making of high complexity when Williams actually provided fitness and exercise training to his clients.

According to the criminal complaint affidavit, Williams recruited potential clients through the use of flyers, the Internet, and word-of-mouth. Once recruited, Williams would typically meet with or speak with the new client over the phone and review their health history and goals for their planned fitness training. Williams would then typically assign a personal trainer to that individual. The personal trainer typically met with the client between one and three times a week for approximately one hour and provided fitness training. Williams would then bill insurance companies for each training session using inaccurate codes and on certain occasions, billed for services that neither he nor his staff, ever provided.

Between November 2012 through August 2017, Williams was paid in excess of $3.9 million in relation to his fraudulent billing of United HealthCare Services, Inc., Aetna, Inc., and Cigna.

We’ll examine these topics across several modules. Those modules, along with the learning objectives, include the following:

- Module 1 examines fraud, its legal elements, major categories, common fraud schemes, and introduces the concept of abuse. The objective is for readers to be able to describe occupational fraud and abuse and to appreciate the complexities of pursuing legal action against fraudsters.

- Module 2 defines forensic accounting and contrasts forensic accounting engagements to fraud examinations. The goal in this module is for readers to be able to articulate the role of forensic accountants.

- Module 3 takes a look at some of the skills necessary to be a forensic accountant or fraud examiner. The goal is for readers to be able to identify the portfolio of required professional skills and to determine the alignment of their personal characteristics.

- Module 4 compares and contrasts auditing with fraud examination and forensic accounting. While understanding the similarities and differences between auditing, fraud examination, and forensic accounting take time, the take-away from module 4 will be the reader’s ability to describe the role of each field and identify the similarities, differences, overlaps, and unique space of each.

- Module 5 offers an overview of the basics of fraud. Topics include the societal costs of fraud and litigation, as well as key metrics and fraud statistics from the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners’ Report to the Nations, a biannual survey of fraud cases. The goal is for readers to recognize the cost of fraud and to develop profiles of fraud schemes, perpetrators, victims, and other relevant fraud-related attributes.

- Module 6 takes an initial look into the examination (investigation) of forensic accounting and fraud issues. The goal is to launch readers on a path toward the detection, investigation, and remediation of forensic accounting issues and fraud red flags.

- Module 7 provides an overview of the key elements of fraud examination. Fraud examination is more than just investigation of allegations and includes prevention, deterrence, detection, and remediation. Readers will be able to describe predication and articulate the activities associated with fraud examination.

Module 1: What Is Fraud?

Imagine that you work in the accounts payable department of your company, and you discover that your boss is padding his reimbursable travel expenses with personal expenses. Consider this: Wal-Mart legend, Thomas Coughlin, who was described as a protégé and old hunting buddy of the company’s late founder, Sam Walton, was forced to resign on March 25, 2005, from Wal-Mart’s Board of Directors. Mr. Coughlin, fifty-five years old at the time, periodically had subordinates create fake invoices to get the company to pay for his personal expenses. The questionable activity appeared to involve dozens of transactions over more than five years, including hunting vacations, custom-made alligator boots, and an expensive dog pen for his family home. Wal-Mart indicated that it found questionable transactions totaling between $100,000 and $500,000. In his last year, Mr. Coughlin’s compensation totaled more than $6 million. Interestingly, Mr. Coughlin was an outspoken critic of corporate chicanery. In 2002, he told the Cleveland Plain Dealer, “Anyone who is taking money from associates and shareholders ought to be shot.”2

Answer these questions:

- What would you do?

- Should you report it to anyone?

- Who could you trust?

- Is this fraud?

- If you don’t report it, are you complicit in fraud?

Fraud, sometimes referred to as the fraudulent act, is an intentional deception, whether by omission or co-mission, that causes its victim to suffer an economic loss and/or the perpetrator to realize a gain. A simple working definition of fraud is “theft by deception.”

Legal Elements of Fraud

Under common law, fraud includes four essential elements:

- A material false statement

- Knowledge that the statement was false when it was spoken

- Reliance on the false statement by the victim

- Damages resulting from the victim’s reliance on the false statement

In the broadest sense, fraud can encompass any crime for gain that uses deception as its principal technique. This deception is implemented through fraud schemes: specific methodologies used to commit and conceal the fraudulent act. There are three ways to relieve a victim of money illegally: by force, trickery, or larceny. Those offenses that employ trickery are frauds.

The legal definition of fraud is the same whether the offense is criminal or civil; the difference is that criminal cases must meet a higher burden of proof. For example, let’s assume an employee who worked in the warehouse of a computer manufacturer stole valuable computer chips when no one was looking and resold them to a competitor. This conduct is certainly illegal, but what law has the employee broken? Has he committed fraud? The answer, of course, is that it depends. Let us briefly review the legal ramifications of the theft.

The legal term for stealing is larceny, which is defined as “felonious stealing, taking and carrying, leading, riding, or driving away with another’s personal property, with the intent to convert it or to deprive the owner thereof.”3 In order to prove that a person has committed larceny, we would need to prove the following four elements:

- There was a taking or carrying away

- of the money or property of another

- without the consent of the owner and

- with the intent to deprive the owner of its use or possession.

In our example, the employee definitely carried away his employer’s property, and we can safely assume that this was done without the employer’s consent. Furthermore, by taking the computer chips from the warehouse and selling them to a third party, the employee clearly demonstrated intent to deprive his employer of the ability to possess and use those chips. Therefore, the employee has committed larceny.

The employee might also be accused of having committed a tort known as conversion.4 Conversion, in the legal sense, is “an unauthorized assumption and exercise of the right of ownership over goods or personal chattels belonging to another, to the alteration of their condition or the exclusion of the owner’s rights.”5 A person commits a conversion when he or she takes possession of property that does not belong to him or her and, thereby, deprives the true owner of the property for any length of time. The employee in our example took possession of the computer chips when he stole them, and, by selling them, he has deprived his employer of that property. Therefore, the employee has also engaged in conversion of the company’s property.

Furthermore, the act of stealing the computer chips also makes the employee an embezzler. “To embezzle means willfully to take, or convert to one’s own use, another’s money or property of which the wrongdoer acquired possession lawfully, by reason of some office or employment or position of trust.” The key words in that definition are “acquired possession lawfully.” In order for an embezzlement to occur, the person who stole the property must have been entitled to possession of the property at the time of the theft. Remember, possession is not the same as ownership. In our example, the employee might be entitled to possess the company’s computer chips (to assemble them, pack them, store them, etc.), but clearly the chips belong to the employer, not the employee. When the employee steals the chips, he has committed embezzlement.

We might also observe that some employees have a recognized fiduciary relationship with their employers under the law. The term fiduciary, according to Black’s Law Dictionary, means “a person holding a character analogous to a trustee, in respect to the trust and confidence involved in it and the scrupulous good faith and candor which it requires. A person is said to act in a ‘fiduciary capacity’ when the business which he transacts, or the money or property which he handles, is not for his own benefit, but for another person, as to whom he stands in a relation implying and necessitating great confidence and trust on the one part and a high degree of good faith on the other part.” In short, a fiduciary is someone who acts for the benefit of another.

Fiduciaries have a duty to act in the best interests of the person whom they represent. When they violate this duty, they can be liable under the tort of breach of fiduciary duty. The elements of this cause of action vary among jurisdictions, but in general, they consist of the following:

- A fiduciary relationship existed between the plaintiff and the defendant

- The defendant (fiduciary) breached his or her duty to the plaintiff

- The breach resulted in either harm to the plaintiff or benefit to the fiduciary

A fiduciary duty is a very high standard of conduct that is not lightly imposed. The duty depends upon the existence of a fiduciary relationship between the two parties. In an employment scenario, a fiduciary relationship is usually found to exist only when the employee is “highly trusted” and enjoys a confidential or special relationship with the employer. Practically speaking, the law generally recognizes a fiduciary duty only for officers and directors of a company, not for ordinary employees. (In some cases, a quasi-fiduciary duty may exist for employees who are in possession of trade secrets; they have a duty not to disclose that confidential information.) The upshot is that the employee in our example most likely would not owe a fiduciary duty to his employer, and therefore he would not be liable for breach of fiduciary duty. However, if the example were changed so that an officer of the company stole a trade secret, that tort might apply.

But what about fraud? Recall that fraud always involves some form of deceit. If the employee in question simply walked out of the warehouse with a box of computer chips under his or her coat, this would not be fraud, because there is no deceit involved. (Although many would consider this a deceitful act, what we’re really talking about when we say deceit, as reflected in the elements of the offense, is some sort of material false statement that the victim relies upon.)

Suppose, however, that before he put the box of computer chips under his coat and walked out of the warehouse, the employee tried to cover his trail by falsifying the company’s inventory records. Now the character of the crime has changed. Those records are a statement of the company’s inventory levels, and the employee has knowingly falsified them. The records are certainly material, because they are used to track the amount of inventory in the warehouse, and the company relies on them to determine how much inventory it has on hand, when it needs to order new inventory, etc. Furthermore, the company has suffered harm as a result of the falsehood, because it now has an inventory shortage of which it is unaware.

Thus, all four attributes of fraud have now been satisfied: the employee has made a material false statement, the employee had knowledge that the statement was false, the company relied upon the statement, and the company has suffered damages. As a matter of law, the employee in question could be charged with a wide range of criminal and civil conduct: fraud, larceny, embezzlement, or conversion. As a practical matter, he or she will probably only be charged with larceny. The point, however, is that occupational fraud always involves deceit, and acts that look like other forms of misconduct, such as larceny, may indeed involve some sort of fraud. Throughout this book, we study not only schemes that have been labeled fraud by courts and legislatures but any acts of deceit by employees that fit our broader definition of occupational fraud and abuse. As you see later in Chapter 1, our recommended investigative approach does not require that you identify the specific law that was violated. Rather, the goal is to examine the relevant evidence with an eye toward demonstrating three attributes of the fraud:

- The scheme or fraud act

- The concealment activity

- The conversion or benefit

This approach ensures a careful and thorough examination of the issue without causing the forensic accountant to make decisions better suited to an attorney’s expertise. We’ll also use a thorough and careful examination of evidence associated with forensic accounting issues; again, this approach permits legal professionals to make determinations of which specific laws are relevant to the case facts and circumstances.

Major Categories of Fraud

- Asset misappropriations involve the theft or misuse of an organization’s assets. (Common examples include skimming cash and checks, stealing inventory, and payroll fraud.)

- Corruption entails the unlawful or wrongful misuse of influence in a business transaction to procure personal benefit, contrary to an individual’s duty to his or her employer or the rights of another. (Common examples include accepting kickbacks and engaging in conflicts of interest.)

- Financial statement fraud and other fraudulent statements involve the intentional misrepresentation of financial or nonfinancial information to mislead others who are relying on it to make economic decisions. (Common examples include overstating revenues, understating liabilities or expenses, or making false promises regarding the safety and prospects of an investment.)

Enron founder Ken Lay and former chief executive officer (CEO) Jeff Skilling were convicted in May 2006 for their respective roles in the energy company’s collapse in 2001. The guilty verdict against Lay included conspiracy to commit securities and wire fraud, but he never served any prison time because he died of a heart attack two months after his conviction. Skilling, however, was sentenced on October 23, 2006, to twenty-four years for conspiracy, fraud, false statements, and insider trading. In addition, Judge Lake ordered Skilling to pay $45 million into a fund for Enron employees. Former Enron chief financial officer (CFO) Andrew Fastow received a relatively light sentence of six years for his role, after cooperating with prosecutors in the conviction of Lay and Skilling.6 Enron was a $60 billion victim of accounting maneuvers and shady business deals that also led to thousands of lost jobs and more than $2 billion in employee pension plan losses.

If you were working at Enron and had knowledge of this fraud, what would you do?

On January 14, 2002, a seven-page memo, written by Sherron Watkins, was referred to in a Houston Chronicle article. This memo had been sent anonymously to Kenneth Lay and begged the question, “Has Enron Become a Risky Place to Work?” For her role as whistleblower, Sherron Watkins was recognized along with WorldCom’s Cynthia Cooper and the FBI’s Coleen Rowley as Time Magazine’s Person of the Year in 2002.

The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners defines financial statement fraud as the intentional, deliberate misstatement, or omission of material facts or accounting data that is misleading and, when considered with all the information made available, that would cause the reader to change or alter his or her judgment or decision.7 In other words, the statement constitutes intentional or reckless conduct, whether by act or omission, that results in material misleading financial statements.8

Even though the specific schemes vary, the major areas involved in financial statement fraud include the following:

| Financial Statement and Reporting Fraud | |

| Net Worth/Net Income Overstatements | Net Worth/Net Income Understatements |

| Fictitious revenue (and related assets) | Understated revenue (and related assets) |

| Improper timing of revenue and expense recognition | Improper timing of revenue and expense recognition |

| Concealed liabilities and expenses | Overstated liabilities and expenses |

| Improper asset valuation, including inappropriate capitalization of expenses | Improper asset valuation, including inappropriate asset write-offs |

| Improper disclosures | Improper disclosures |

The essential characteristics of financial statement fraud are (1) the misstatement is material and intentional and (2) users of the financial statements have been misled.

In the early 2000s, the financial press had an abundance of examples of fraudulent financial reporting.

These include Enron, WorldCom, Adelphia, Tyco, and others. The common theme of all these scandals was a management team that was willing to “work the system” for its own benefit and a wide range of stakeholders—including employees, creditors, investors, and entire communities—that are still reeling from the losses. In response, Congress passed the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) in 2002. SOX legislation was aimed at auditing firms, corporate governance, executive management (CEOs and CFOs), officers, and directors. The assessment of internal controls, preservation of evidence, whistleblower protection, and increased penalties for securities fraud became a part of the new business landscape.

The ACFE 2016 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse noted that financial fraud tends to be the least frequent of all frauds, accounting for only about 10%. However, the median loss for financial statement fraud is approximately $1 million, more than eight times larger than the typical asset misappropriation and approximately four times larger than the typical corruption scheme. In addition, when financial statement fraud has been identified, in 80% of the cases, other types of fraud are also being perpetrated.

Common Fraud Schemes

Table 1-1 depicts the most common fraud schemes.

TABLE 1-1 Common Fraud Schemes

| Fraud Acts |

| Asset Misappropriation |

| Cash |

| Larceny (theft) |

| Skimming (removal of cash before it hits books): Sales, A/R, Refunds, and Other |

| Fraudulent Disbursement |

| Billing Schemes—including shell companies, fictitious vendors, personal purchases |

| Payroll Schemes—ghost employees, commission schemes, workers compensation, and false hours and wages |

| Expense Reimbursement Schemes—including overstated expenses, fictitious expenses, and multiple reimbursements |

| Check Tampering |

| Register Disbursements including false voids and refunds |

| Inventory and Other Assets |

| Inappropriate Use |

| Larceny (theft) |

| Corruption |

| Conflicts of Interest (unreported or undisclosed) |

| Bribery |

| Illegal Gratuities |

| Economic Extortion |

| False Statements |

| Fraudulent Financial Statements |

| False Representations (e.g., employment credentials, contracts, identification) |

| Specific Fraud Contexts |

| Bankruptcy Fraud |

| Contract and Procurement Fraud |

| Money Laundering |

| Tax Fraud |

| Investment Scams |

| Terrorist Financing |

| Consumer Fraud |

| Identity Theft |

| Check and Credit Card Fraud |

| Computer and Internet Fraud |

| Divorce Fraud (including hidden assets) |

| Intellectual Property |

| Business Valuation Fraud |

| Noteworthy Industry-Specific Fraud |

| Financial Institutions |

| Insurance Fraud |

| Health-Care Fraud |

| Securities Fraud |

| Public Sector Fraud |

Suspected frauds can be categorized by a number of different methods, but they are usually referred to as either internal or external frauds. The latter refers to offenses committed by individuals against other individuals (e.g., con schemes), offenses by individuals against organizations (e.g., insurance fraud), or organizations against individuals (e.g., consumer frauds). Internal fraud refers to occupational fraud committed by one or more employees of an organization; this is the most costly and most common fraud. These crimes are more commonly referred to as occupational fraud and abuse.

The Fraud Tree was developed in 1996 by Dr. Joseph T. Wells, Founder and Chairman of the ACFE (Figure 1-1). This tool for classifying major categories of fraud has withstood the test of time. It helps readers understand fraud based on the type of scheme (assets misappropriation, corruption, and financial statement fraud) as well as important subcategories. Each type of fraud has specific elements required to perpetrate and conceal the fraud. As such, detection can be targeted by likely symptoms and investigation can be tailored.

FIGURE 1-1 Occupational fraud and abuse classification system (fraud tree)

What Is the Difference Between Fraud and Abuse?

Obviously, not all misconduct in the workplace amounts to fraud. There is a litany of abusive practices that plague organizations, causing lost dollars or resources, but that do not actually constitute fraud. As any employer knows, it is hardly out of the ordinary for employees to do any of the following:

- Use equipment belonging to the organization

- Surf the Internet while at work

- Attend to personal business during working hours

- Take a long lunch, or a break, without approval

- Come to work late, or leave early

- Use sick leave when not sick

- Do slow or sloppy work

- Use employee discounts to purchase goods for friends and relatives

- Work under the influence of alcohol or drugs

The term abuse has taken on a largely amorphous meaning over the years, frequently being used to describe any misconduct that does not fall into a clearly defined category of wrongdoing. Webster’s definition of abuse might surprise you. From the Latin word abusus, to consume, it means: “1. A deceitful act, deception; 2. A corrupt practice or custom; 3. Improper use or treatment, misuse.” To deceive is “to be false; to fail to fulfill; to cheat; to cause to accept as true or valid what is false or invalid.”

Given the commonality of the language describing both fraud and abuse, what are the key differences? Here is an example to illustrate: Suppose that a teller was employed by a bank and stole $100 from her cash drawer. We would define that broadly as fraud. But if she earns $500 a week and falsely calls in sick one day, we might call that abuse—even though each act has the exact same economic impact to the company—in this case, $100.

And, of course, each offense requires a dishonest intent on the part of the employee to victimize the company. Look at the way in which each is typically handled within an organization. In the case of the embezzlement, the employee would likely be terminated; there is also a possibility (albeit remote) that she would be prosecuted. But in the case in which the employee misuses her sick time, she would likely be reprimanded, or her pay might be docked for the day.

We can also change the abuse example slightly. Let’s say the employee works for a governmental agency instead of the private sector. Sick leave abuse—in its strictest interpretation—would be fraud against the government. After all, the employee has made a false statement (about her ability to work) for financial gain (to keep from getting docked). Government agencies can and have prosecuted flagrant instances of sick leave abuse. Misuse or theft of public funds in any form is a serious matter, and the prosecutorial thresholds are surprisingly low.

Module 2: What Is Forensic Accounting?

A call comes in from a nationally known insurance company. Claims Agent Kathleen begins: “I have a problem and you were recommended to me. One of my insureds near your locale submitted an insurance claim related to an accounts receivable rider. The insurance claim totals more than $1 million, and they are claiming that the alleged perpetrator did not take any money and that their investigation to date indicates that no money is missing from the company. Can you assist with an investigation of this claim?”

She asks for your help to do the following:

- Verify the facts and circumstances surrounding the claim presented by the insured

- Determine whether accounting records have been physically destroyed

- To the best of your ability, determine whether this is a misappropriation or theft of funds

- If this is a theft of funds, attempt to determine by whom

Forensic accounting is the application of financial principles and theories to facts or hypotheses at issue in a legal dispute and consists of two primary functions:

- Litigation advisory services, which recognizes the role of the forensic accounting professional as an expert or consultant

- Investigative services, which makes use of the forensic accounting professional’s skills and may or may not lead to courtroom testimony

Forensic accounting may involve either an attest or consulting engagement.9 According to the AICPA, Forensic and Valuation Services (FVS) professionals provide educational, technical, functional, and industry-specific services that often apply to occupational fraud, corruption, and abuse and to financial statement fraud cases. FVS professionals may assist attorneys with assembling the financial information necessary either to bolster a case (if hired by the plaintiff) or to undercut it (if hired by the defendant). They can provide varying levels of support—from technical analysis and data mining, to a broader approach that may include developing litigation strategies, arguments, and testimony in civil and criminal cases. Engagements may involve services for criminal, civil, or administrative cases that entail economic damage claims, workplace or matrimonial disputes, or asset and business valuations.10

Forensic and litigation advisory services require interaction with attorneys throughout the engagement. Excellent communication skills are essential for effective mediation, arbitration, negotiations, depositions, and courtroom testimony. These communication skills encompass the use of a variety of means by which to express the facts of the case—oral, written, pictures, and graphs. Like all fraud and forensic accounting work, there is an adversarial nature to the engagements, and professionals can expect that their work will be carefully scrutinized by the opposing side.

Nonfraud Forensic Accounting and Litigation Advisory Engagements

The forensic accountant can be expected to participate in any legal action that involves money, following the money, performance measurement, valuation of assets, cost measurement and any other aspect related to a litigant’s finances, financial performance and/or financial condition. In some cases, the finances of the plaintiff are at issue; in some cases, the finances of the defendant are at issue; and in some disputes, the finances of both are under scrutiny, and the forensic accountants may be asked to analyze, compare, and contrast both the plaintiff’s and defendant’s finances and financial condition.

Some of the typical forensic and litigation advisory services may be summarized as follows:

- Damage claims made by plaintiffs and in countersuits by defendants

- Workplace issues, such as lost wages, disability, and wrongful death

- Assets and business valuations

- Costs and lost profits associated with construction delays

- Costs and lost profits resulting from business interruptions

- Insurance claims

- Divorce and matrimonial issues

- Fraud

- Antitrust actions

- Intellectual property infringement and other disputes

- Environmental issues

- Tax disputes

- Employment issues related to lost income and wages

The issues addressed by a forensic accountant during litigation may or may not be central to the allegations made by the plaintiff’s or defense attorneys, but they may serve to provide a greater understanding of the motivations of the parties, other than those motivation claims made publicly, in court filings and in case pleadings.

Module 3: The Professional’s Skill Set

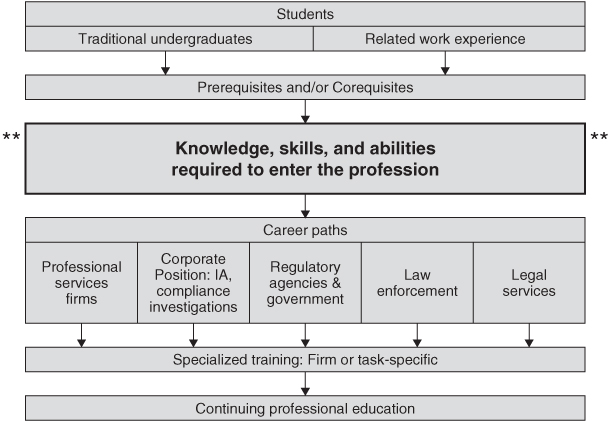

Forensic accounting and fraud examination require at least three major skill types: technical competence, investigative, and communication.

First, the technical skills of accounting, auditing, finance, quantitative methods, and certain areas of the law and research provide the foundation upon which theories of the case are examined.

Second, forensic accountants and fraud examiners use investigative skills for the collection, analysis, and evaluation of evidential matter, and critical thinking to interpret the findings.

Third, the ability to effectively and succinctly communicate the results of her work is critical to the professional’s success.

Critical thinking, sometimes referred to as lateral thinking or thinking “outside the box,” is a disciplined approach to problem solving. It is used as a foundation to guide our thought process and related actions. Forensic accountants and fraud examiners operationalize these skills using the “fraud theory” approach which incorporates the hypothesis-evidence matrix.

Module 4: The Role of Auditing, Fraud Examination, and Forensic Accounting

Fraud examination, forensic accounting, and traditional auditing are interrelated, yet they have characteristics that are separate and distinct. All require interdisciplinary skills to succeed—professionals in any of these fields must possess a capacity for working with numbers, words, and people.

Financial statement auditing seeks to ensure that financial statements are free from material misstatement. Audit procedures, as outlined in PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 5 or AICPA Statement on Auditing Standards (SAS) No. 99 (AU Section 316), require that the auditor undertake a fraud-risk assessment. However, under generally accepted auditing standards (GAAS) auditors are not currently responsible for planning and performing auditing procedures to detect immaterial misstatements, regardless of whether they are caused by error or fraud. Allegations of financial statement fraud are often resolved through court action, and auditors may be called into court to testify on behalf of a client or to defend their audit work, a point at which auditing, fraud examination, and forensic accounting intersect.

However, each discipline also encompasses separate and unique functional aspects. For example, fraud examiners are generally called in after there is reason to believe that fraud has occurred or is occurring, and often assist in fraud prevention and deterrence efforts that do not involve the audit of nonpublic companies or the legal system. Forensic accounting professionals calculate economic damages, business or asset valuations, and provide litigation advisory services that may not involve allegations of fraud. Finally, most audits are completed without uncovering financial statement fraud or involving the legal system. Thus, as graphically presented in Figure 1-2, auditing, fraud examination, and forensic accounting often use the same tools, but they also have responsibilities independent of the other.

FIGURE 1-2 Auditing, fraud examination, and forensic accounting

The interrelationship among auditing, fraud examination, and forensic accounting is dynamic and changes over time because of political, social, and cultural pressures. Independent auditors operate in an environment impacted by Dodd-Frank, SOX, and SAS 99; consequently, they are expected to have adequate knowledge and skills in the area of fraud detection and deterrence. In addition, auditors, fraud examiners, and forensic accountants often have skill sets in multiple areas and are able to leverage their skills and abilities from one area when working in others.12

Fraud examination is the discipline of resolving allegations of fraud from tips, complaints, or accounting clues. It involves obtaining documentary evidence, interviewing witnesses and potential suspects, writing investigative reports, testifying about investigation findings, and assisting in the general detection and prevention of fraud. Fraud examination has overlap with the field of forensic accounting—the latter also uses financial knowledge, skills, and abilities for courtroom purposes. Forensic accounting may involve not only the investigation of potential fraud, but a host of other litigation support services.

Similarly, fraud examination and auditing are interrelated, but fraud examination encompasses much more than just the review of financial data. It involves techniques such as interviews, statement analyses, public records searches, and forensic document examination. There are also significant differences between the three disciplines in terms of their scope, objectives, and underlying presumptions. Table 1-2 summarizes these differences.

TABLE 1-2 Differences between Auditing, Fraud Examination, and Forensic accounting

| Issue | Auditing | Fraud Examination | Forensic Accounting |

| Timing | Recurring | Nonrecurring | Nonrecurring |

| Audits occur on a regular, recurring basis. | Fraud examinations are conducted only with sufficient predication. | Forensic accounting engagements are conducted only after allegation of misconduct. | |

| Scope | General | Specific | Specific |

| The examination of financial statements for material misstatements. | The purpose of the examination is to resolve specific allegations. | The purpose of the examination is to resolve specific allegations. | |

| Objective | Opinion | Affix blame | Determine financial impact |

| An audit is generally conducted for the purpose of expressing an opinion on the financial statements and related information. | The fraud examination’s goal is to determine whether fraud has occurred and who is likely responsible. | The forensic accounting professional’s goal is to determine whether the allegations are reasonable based on the financial evidence and, if so, the financial impact of the allegations. | |

| Relationship | Nonadversarial but skeptical | Adversarial | Independent |

| Historically, the audit process was nonadversarial. Since SOX and SAS 99, auditors use professional skepticism as a guide. | Fraud examinations, because they involve efforts to affix blame, are adversarial in nature. | A forensic accounting professional calculates financial impact based on formulaic assumptions. | |

| Methodology | Audit techniques | Fraud examination techniques | Forensic accounting techniques |

| Audits are conducted primarily by examining financial data using GAAS. | Gathering the required financial and nonfinancial evidence to affix culpability. | Gathering the required financial and nonfinancial evidence to examine the allegations independently and determine their financial impact. | |

| Presumption | Professional Skepticism | Proof | Proof |

| Auditors are required to approach audits with professional skepticism, as outlined in GAAS. | Fraud examiners approach the resolution of a fraud by attempting to gather sufficient evidence to support or refute an allegation of fraud. | Forensic accounting professionals will attempt to gather sufficient evidence to support or refute the allegation and related damages. |

Nevertheless, successful auditors, fraud examiners, and forensic accountants have many similar attributes; they are all diligent, detail-oriented, organized, critical thinkers, excellent listeners, and good communicators.

Module 5: The Basics of Fraud

Brian Lee excelled as a top-notch plastic surgeon. Lee practiced out of a large physician-owned clinic of various specialties. As its top producer, Lee billed more than $1 million annually and took home $300,000 to $800,000 per year in salary and bonus. During one four-year stretch, Lee also kept his own secret stash of unrecorded revenue—possibly hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Because plastic surgery is considered by many health insurance plans to be an elective procedure, patients were required to pay their portion of the surgical fees in advance. The case that ultimately nailed Brian Lee involved Rita Mae Givens. Givens had elective rhinoplasty, surgery to reshape her nose, and, during her recovery, she reviewed her insurance policy and discovered that this procedure might be covered under her health insurance or, at least, counted toward her yearly deductible. In pursuit of seeking insurance reimbursement for her surgery, Givens decided to file a claim. She called the clinic office to request a copy of her invoice, but the cashier could find no record of her surgery or billing records. Despite the missing records, Givens had her cancelled check, proof that her charges had been paid. An investigator was called in, and Dr. Lee was interviewed several times over the course of the investigation. Eventually, he confessed to stealing payments from the elective surgical procedures, for which billing records were not required, particularly when payment was made in cash or by a check made payable to his name. Why would a successful, top-performing surgeon risk it all? Dr. Lee stated that his father and brother were both very successful; wealth was the family’s obsession, and one-upmanship was the family’s game. This competition drove each of them to see who could amass the most, drive the best cars, live in the nicest homes, and travel to the most exotic vacation spots.

Unfortunately, Lee took the game one step further and was willing to commit grand larceny to win. Luckily for Lee, the other doctors at the clinic decided not to prosecute or terminate their top moneymaker. Lee made full restitution of the money he had stolen, and the clinic instituted new payment procedures. Ironically, Dr. Lee admitted to the investigator that, if given the opportunity, he would probably do it again.13

The Cost of Fraud and Other Litigation

Based on world GDP, in 2014, the ACFE estimated that the cost of fraud may be as high as $3.7 trillion annually. Even though this number is staggering in size, it hides the potentially disastrous impact at the organizational level. For example, if a company with a 10% net operating margin is a victim of a $500,000 fraud or loses a comparable amount as a result of a lawsuit, that company must generate incremental sales of $5 million to make up the lost dollars. If the selling price of the average product is $1,000 (a computer, for example), the company would need to sell an additional 5,000 units of product.

Organizations incur costs to produce and sell their products or services. These costs run the gamut: labor, taxes, advertising, occupancy, raw materials, research and development—and, yes, fraud and litigation. The cost of fraud and litigation, however, are fundamentally different from the other costs—the true expenses of fraud and litigation are hidden, even if a portion of the cost is reflected in the profit and loss figures. The indirect costs of fraud and litigation can have a far-reaching impact—employees may lose their jobs; the company may have difficulty getting loans, mortgages, and other forms of credit; the company’s reputation may be adversely affected; and the company may become the target of broader investigations. With regard to either litigation or fraud, prevention and deterrence are the best medicines. By the time a formal investigation is launched and the allegations are addressed within the legal arena, the organization has already incurred substantial costs.

ACFE 2016 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse

The ACFE began a major study of occupational fraud cases in 1993, with the primary goal of classifying occupational frauds and abuses by the methods used to commit them. There were other objectives, too. One was to get an idea of how antifraud professionals—CFEs—perceive the fraud problems in their own companies.

The ACFE 2016 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse is a result of what has now become a biannual national fraud survey of those professionals who deal with fraud and abuse on a daily basis.

Fraud Schemes Corresponding With the Fraud Tree

The ACFE highlights three major types of occupational fraud and abuse: asset misappropriation, corruption, and financial reporting fraud. The relative frequency and losses associated with each are as follows:

| Fraud Scheme Category | Percentage | Median Losses |

| Asset Misappropriation | 85 | $130,000 |

| Corruption | 37 | $200,000 |

| Financial Reporting Fraud | 9 | $1,000,000 |

These percentages do not add up to 100% because many frauds involve multiple schemes. Within asset misappropriation, which has the most diversity, the heat map of frequency and loss (Figure 1-3) provides a broader view of the risk to victims.

FIGURE 1-3 Frequency and median loss of asset misappropriation subschemes

Corruption is sometimes hypothesized to be especially common in cultures where “gratuities” are part of the business climate. As such, Figure 1-4 offers insight into corruption by regions of the world.

FIGURE 1-4 Frequency and median loss of corruption cases by region

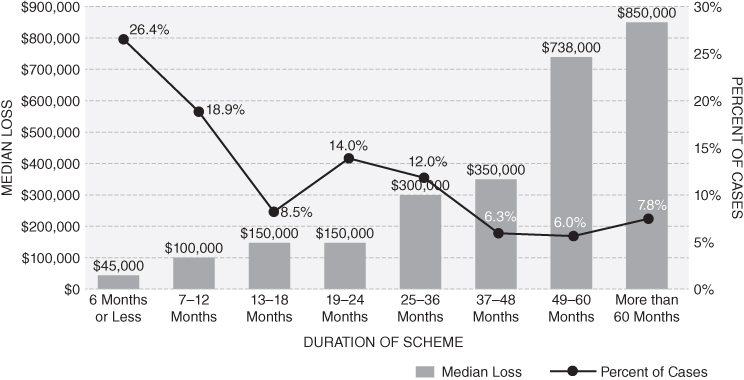

As the duration of the fraud lengthens, the cost of fraud increases. As noted in Figure 1-5, organizational efforts to detect fraud earlier should result in less impact. The median fraud lasts about eighteen months, according to the ACFE.

FIGURE 1-5 Frequency and median loss based on duration of fraud

For the first time in the history of the Report to the Nations, the 2016 survey queried CFEs on the most common tactics to conceal fraud schemes. As the graphic in Figure 1-6 notes, the most common concealment schemes are “old fashioned” document-based efforts. Across time, antifraud professionals might see more electronic (technological) concealment. In the near term, traditional red flags are likely going to be grounded in physical evidence. While some differences across fraud categories were observed, generally, concealment is similar for asset misappropriation, corruption, and financial fraud schemes.

FIGURE 1-6 Concealment method by scheme type

Tips (i.e., whistleblowing, hotlines) remain firmly as the most frequent means by which fraud is detected as shown in Figure 1-7. In the 2016 data, internal audit (16.5%) edged out management review (13.4%) as the second-most common detection method. Historically, external audits detected only about 3% of frauds. This is likely due to the materiality threshold incorporated into the external audit process. As noted above, the median loss, especially for asset misappropriation which is the highest frequency of fraud at 85%, is relatively low. As such, external auditors may not sample and examine transactions associated with the fraud scheme included in the ACFE study. The role of the external audit, as it relates to detecting fraud, is the subject of much professional and researcher attention.

FIGURE 1-7 Initial detection of occupational frauds

The following chart offers a deeper look at tips by identifying the source of the tip.

| Source of the Tip | Percentage |

| Employee | 51.5 |

| Customer | 17.8 |

| Anonymous | 14.0 |

| Other | 12.6 |

| Vendor | 9.9 |

| Shareholder/Owner | 2.7 |

| Competitor | 1.6 |

The Perpetrators of Fraud

Another goal of the ACFE survey was to gather demographics on the perpetrators: How old are they? How well educated? What is the gender breakdown of offenders? Were there any identifiable correlations with respect to the offenders? Participants in the 2016 National Fraud Survey provided the following information on the perpetrators’ position, gender, age, education, tenure, and criminal histories.

The Effect of Position on Median Loss

Fraud losses tended to rise based on the perpetrator’s level of authority within an organization (see Figure 1-8). Generally, employees with the highest levels of authority are the highest paid as well. Therefore, it was not a surprise to find a positive correlation between the perpetrators’ position and the size of fraud losses.

FIGURE 1-8 Position of perpetrator—frequency and median loss

The lowest median loss of $65,000 was found in frauds committed by employees. Although the median loss in schemes committed by managers reached $173,000, the median loss skyrocketed to $703,000 for executives/owners. Approximately 18.9% of the schemes are committed by executives/owners.

The Effect of Gender on Median Loss

The 2016 ACFE Report to the Nation showed that male employees caused median losses that were more than twice as large as those of female employees; the median loss in a scheme caused by a male employee was $187,000, whereas the median loss caused by a female employee was $100,000. The most logical explanation for this disparity seems to be the “glass ceiling” phenomenon. Generally, in the United States, men occupy higher-paying positions than their female counterparts. And as we have seen, there is a direct correlation between median loss and position. Furthermore, in addition to higher median losses in schemes where males were the principal perpetrators, men accounted for 69.0% of the cases, as Figure 1-9 shows.

FIGURE 1-9 Gender of perpetrator—frequency

The Effect of Age on Median Loss

The age range of fraud perpetrators in the study ran the gamut from young to senior citizen. There was a strong correlation between the age of the perpetrator and the size of the median loss (see Figure 1-10), which was consistent with findings from previous reports. Although there were very few cases committed by employees over the age of sixty (2.5%), the median loss in those schemes was $630,000. By comparison, the median loss in frauds committed by those twenty-five or younger was $15,000. As with position and gender, age is likely a secondary factor in predicting the loss associated with an occupational fraud, generally reflecting the perpetrator’s position and tenure within an organization.

FIGURE 1-10 Age of perpetrator—frequency and median loss

Although frauds committed by those in the older age groups were the most costly on average, almost two-thirds of the frauds reported were committed by employees 31−50 years old. The median age among perpetrators was 40.

The Effect of Education on Median Loss

As employees’ education levels rose, so did the losses from their frauds (Figure 1-11). The median loss in schemes committed by those with only a high school education was $90,000, whereas the median loss caused by employees with a postgraduate education was $300,000. This trend was to be expected, given that those with higher education levels tend to occupy positions with higher levels of authority.

FIGURE 1-11 Education level of perpetrator—frequency and median loss

The Effect of Collusion on Median Loss

It was not surprising to see that in cases involving more than one perpetrator, fraud losses rose substantially. The majority of 2016 survey cases (52.9%) only involved a single perpetrator, but when two or more persons conspired, the median loss was more than seven times higher (see Figure 1-12).

FIGURE 1-12 Number of perpetrators—frequency and median loss

Criminal History of the Perpetrators

Most people who commit occupational fraud are first-time offenders. Only 5.2% of the perpetrators identified in the 2016 study were known to have been convicted of a previous fraud-related offense. Another 5.5% of the perpetrators had previously been charged but never convicted. These figures are consistent with previous studies. It is also consistent with Cressey’s model, in which occupational offenders do not perceive themselves as lawbreakers. With regard to employment history, approximately 8.3% had been previously terminated for fraud-related offenses.

The ACFE presented survey respondents with a list of 17 common behavioral red flags associated with occupational fraud and asked them to identify which, if any, of these warning signs had been displayed by the perpetrator before the fraud was detected. In more than 91% of cases, at least one behavioral red flag was identified prior to detection, and in 57% of cases two or more red flags were seen. The behavioral red flags and their frequency are presented in Figure 1-13.

FIGURE 1-13 Behavioral red flags displayed by perpetrators

The Victims

The victims of occupational fraud are organizations that are defrauded by those they employ. The ACFE’s 2016 survey asked respondents to provide information on, among other things, the size of organizations that were victimized, as well as the antifraud measures those organizations had in place at the time of the frauds.

Median Loss Based on Type of Organization

Private companies can face challenges in deterring and detecting fraud that differ significantly from those of other organizations. The data show that these private organizations tend to suffer disproportionately large fraud incidents—the median loss for fraud cases attacking private organizations was $180,000, similar to that of public companies ($178,000). This exceeded the median loss for cases in other organization types: government, not-for-profit and other (Figure 1-14).

FIGURE 1-14 Type of victim organization—frequency and median loss

Median Loss Based on Size of the Organization

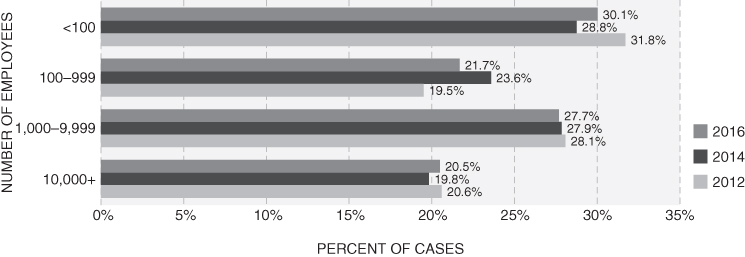

Small businesses (those with fewer than 100 employees) tend to suffer a disproportionately large number of fraud incidents and fraud losses, similar to findings in prior reports. One exception: companies with 100–999 employees (for the 2016 survey only) had median fraud losses that exceeded those of smaller organizations by $36,000 (see Figures 1-15 and 1-16).

FIGURE 1-15 Size of victim organization—frequency

FIGURE 1-16 Size of victim organization—median loss

The data for median loss per number of employees confirm what was always suspected. Antifraud professionals logically conclude that small organizations are particularly vulnerable to occupational fraud and abuse. The results from fraud surveys bear this out: losses in the smallest companies were comparable to, or greater than, those in organizations with the largest number of employees. It is suspected that this phenomenon exists for two reasons. First, smaller businesses have fewer divisions of responsibility; therefore, fewer people must perform more functions. One of the most common types of fraud encountered in these studies involved small business operations that had a one-person accounting department—that employee writes checks, reconciles the accounts, and posts to the books. An entry-level accounting student could spot the internal control deficiencies in that scenario, but apparently many small business owners cannot or do not.

Which brings up the second reason losses are so high in small organizations: There is a greater degree of trust inherent in a situation where everyone knows one another personally. None of us like to think that our coworkers would, or do, commit these criminal offenses. Our defenses are relaxed because we generally trust those we know. There again is the dichotomy of fraud: it cannot occur without trust, but neither can commerce. Trust is an essential element in business—we can, and do, make handshake deals every day. Economic transactions simply cannot occur without trust. The key is seeking the right balance between too much, and too little, trust.

The Impact of Antifraud Measures on Median Loss

CFEs who participated in the ACFE’s fraud surveys were asked to identify which, if any, of several common antifraud measures were utilized by the victim organizations at the time the reported frauds occurred. The median loss was determined for schemes depending on whether each antifraud measure was in place or not (excluding other factors).

The most common antifraud measure was the external audit of financial statements, utilized by approximately 81.7% of the victims, followed by a formal code of conduct, which was implemented by 81.1% of victim organizations (Figure 1-17). Organizations that implemented these controls noted median losses that were 14.3% and 40% lower, respectively, than those of organizations lacking these controls. Interestingly, the three controls associated with the largest reduction in median losses—proactive data monitoring/analysis (big data and data analytics), management review, and hotlines—were not among the most commonly implemented antifraud controls.

| Control | Percent of Cases | Control in Place | Control Not in Place | Percent Reduction |

| Proactive Data Monitoring/Analysis | 36.7% | $92,000 | $200,000 | 54.0% |

| Management Review | 64.7% | $100,000 | $200,000 | 50.0% |

| Hotline | 60.1% | $100,000 | $200,000 | 50.0% |

| Management Certification of Financial Statements | 71.9% | $104,000 | $205,000 | 49.3% |

| Surprise Audits | 37.8% | $100,000 | $195,000 | 48.7% |

| Dedicated Fraud Department, Function, or Team | 41.2% | $100,000 | $192,000 | 47.9% |

| Job Rotation/Mandatory Vacation | 19.4% | $89,000 | $170,000 | 47.6% |

| External Audit of Internal Controls over Financial Reporting | 67.6% | $105,000 | $200,000 | 47.5% |

| Fraud Training for Managers/Executives | 51.3% | $100,000 | $190,000 | 47.4% |

| Fraud Training for Employees | 51.6% | $100,000 | $188,000 | 46.8% |

| Formal Fraud Risk Assessments | 39.3% | $100,000 | $187,000 | 46.5% |

| Employee Support Programs | 56.1% | $100,000 | $183,000 | 45.4% |

| Anti-fraud Policy | 49.6% | $100,000 | $175,000 | 42.9% |

| Internal Audit Department | 73.7% | $123,000 | $215,000 | 42.8% |

| Code of Conduct | 81.1% | $120,000 | $200,000 | 40.0% |

| Rewards for Whistleblowers | 12.1% | $100,000 | $163,000 | 38.7% |

| Independent Audit Committee | 62.5% | $114,000 | $180,000 | 36.7% |

| External Audit of Financial Statements | 81.7% | $150,000 | $175,000 | 14.3% |

FIGURE 1-17 Effectiveness of controls

Remediation

A crucial step in the remediation process is understanding how a fraud occurred, as well as how to prevent and deter future occurrences. In hindsight, it can be difficult to pinpoint the exact system breakdowns that allowed a fraud to occur. However, learning from past fraud incidents is necessary to better prevent and detect future fraud schemes. Consequently, the ACFE survey asks respondents for their perspective on the internal control weaknesses at the victim organization that contributed to the fraudster’s ability to perpetrate the scheme. A clear lack of internal controls was cited as the primary issue by 29.3%, with another 20.3% stating that internal controls were present but had been overridden by the perpetrator (see Figure 1-18).

FIGURE 1-18 Primary internal control weakness observed by CFE

Remediation: Case Results

Another step in the remediation process is for the antifraud professional to assist with the civil and criminal processes. A common complaint among those who investigate fraud is that organizations and law enforcement do not do enough to punish fraud and other white-collar offenses. This has contributed to an increase in fraud occurrences—or so the argument goes—because potential offenders are not deterred by weak or nonexistent sanctions faced by those caught committing fraud. Leaving aside the debate as to what factors are effective in deterring fraud, the survey sought to measure how organizations responded to employees who had defrauded them. One of the criteria for cases in the study was that the CFE had to be reasonably certain that the perpetrator in the case had been identified.

Criminal Prosecutions and Their Outcome

In 59.3% of the cases, the victim organization referred the case to law enforcement authorities.

For cases that were referred to law enforcement authorities, a large number of those cases were still pending at the time of the survey as shown in Figure 1-19. However, for those cases that were resolved, the percentage of defendants who pleaded guilty or no contest has remained fairly constant over time. The rate of cases in which authorities declined to prosecute dropped from 19.2% in 2012 to 13.3% in 2016. Combining guilty pleas and convictions at trial, 76.4% of cases submitted for prosecution resulted in a finding of guilt in 2016, while 2.3% of such prosecutions ended in acquittal. Although the percentage of cases referred to prosecution decreased gradually from the 2012 to the 2016 reports, the percentage of cases that prosecutors successfully pursued increased.14

FIGURE 1-19 Results of cases referred to law enforcement

No Legal Action Taken

One goal of the ACFE study was to try to determine why organizations decline to take legal action against occupational fraudsters. In cases where no legal action was taken, the survey provided respondents with a list of commonly cited explanations and asked them to mark any that applied to their case. Figure 1-20 summarizes the results. Fear of bad publicity (39.0%) was the most commonly cited reason, followed by internal discipline was sufficient (35.5%) and a private settlement being reached (23.3%).

FIGURE 1-20 Reason(s) cases not referred to law enforcement

Module 6: The Investigation

The Mindset: Critical Thinking and Professional Skepticism

As previously noted, we observe that individuals who commit fraud look exactly like us, the average Joe or Jane. If typical fraudsters have no distinguishing outward characteristics to identify them as such, how are we to approach an engagement to detect fraud?

It can be challenging to conduct a forensic accounting engagement or fraud examination unless the investigator is prepared to look beyond his or her value system. In short, the most effective way to catch a fraudster, is to think like one. In a forensic accounting engagement, such as a breach of a contract, the examiner needs to focus on what actions were taken, when they were taken, and if the underlying facts and circumstances are consistent with the actions of the plaintiff or defendant.

PCAOB AS 2401.13 states that “Due professional care requires the auditor to exercise professional skepticism.” Because of the characteristics of fraud, the auditor should conduct the engagement “with a mindset that recognizes the possibility that a material misstatement due to fraud could be present.” It also requires an “ongoing questioning” of whether information the auditor obtains could suggest a material misstatement as a result of fraud.

Professional skepticism can be broken into three attributes:

- Recognition that fraud may be present. In the forensic accounting arena, it is recognition that the plaintiff and/or the defendant may be masking the true underlying story that requires a thorough analysis of the evidence

- An attitude that includes a questioning mind and a critical assessment of the evidence

- A commitment to persuasive evidence. This commitment requires the fraud examiner or forensic accountant to go the extra mile to tie up all loose ends

At a minimum, professional skepticism is a neutral but disciplined approach to detection and investigation. AS 2401 suggests that an auditor neither assumes that management is dishonest nor assumes unquestioned honesty. Professional skepticism, conceptually, drives forensic accounting engagements; keeping an open mind and letting the evidence guide one’s opinions and conclusions. In practice, professional skepticism, particularly recognition, requires that the fraud examiner or forensic accountant “pull on a thread.”

Loose threads: When you pull on a loose thread, a knitted blanket may unravel, a shirt may pucker and be ruined, or a sweater may end up with a hole. Red flags are like loose thread: pull and see what happens; you just might unravel a fraud, ruin a fraudster’s modus operandi, or blow a hole in a fraud scheme. Red flags are like loose threads: left alone, no one may notice, and a fraudster or untruthful litigant can operate unimpeded. A diligent fraud professional or forensic accountant who pulls on a thread may save a company millions of dollars.

Fraud Risk Factors and “Red Flags”

What do these loose threads look like in practice? Fraud professionals and forensic accountants refer to loose threads as anomalies, relatively small indicators, facts, figures, relationships, patterns, and breaks in patterns, suggesting that something may not be right or that the arguments being made by litigants may not be the full story. These anomalies are often referred to as red flags.

Red flags are defined as a warning signal or something that demands attention or provokes an irritated reaction. Although the origins of the term red flag are a matter of dispute, it is believed that, in the 1300s, Norman ships would fly red streamers to indicate that they would “take no quarter” in battle. This meaning continued into the seventeenth century, by which time the flag had been adopted by pirates, who would hoist the “Jolly Roger” to intimidate their foes. If the victims chose to fight rather than submit to boarding, the pirates would raise the red flag to indicate that, once the ship had been captured, no man would be spared. Later it came to symbolize a less bloodthirsty message and merely indicated readiness for battle. From the seventeenth century, the red flag became known as the “flag of defiance.” It was raised in cities and castles under siege to indicate that there would be “no surrender.”15

Fraud professionals and forensic accountants use the term red flags synonymously with symptoms and badges of fraud. Symptoms of fraud may be divided into at least six categories: unexplained accounting anomalies, exploited internal control weaknesses, identified analytical anomalies where nonfinancial data do not correlate with financial data, observed extravagant lifestyles, observed unusual behaviors, and anomalies communicated via tips and complaints.

Although red flags have been traditionally associated with fraudulent situations, forensic accountants are also on the lookout for evidence that is inconsistent with their client’s version of what happened. As independent experts, forensic accountants need to look for evidence that runs counter to their client’s claims. Opposing council is always looking for weaknesses in your client’s case, so whether the professional is investigating fraud or other litigation issues, it is critical that the forensic accountant maintain a sense of professional skepticism, look for red flags, and pull on loose threads.

Fraud risk factors generally fall into three categories:

- Motivational: Is management focused on short-term results or personal gain?

- Situational: Is there ample opportunity for fraud?

- Behavioral: Is there a company culture for a high tolerance of risk?

Evidence-Based Decision Making

Evidence and other legal issues are explored in depth in a later chapter. For now, we’ll use the information in Black’s Law Dictionary, which defines evidence as anything perceivable by the five senses and any proof—such as testimony of witnesses, records, documents, facts, data, or tangible objects—legally presented at trial to prove a contention and induce a belief in the minds of a jury.16 Following the issues of critical thinking and professional skepticism is that of a commitment to evidence-based decision making. One of the best ways to ruin an investigation fails to gain a conviction, or lose a civil case is to base investigative conclusions on logic and conjecture. Many people have tried to convict an alleged perpetrator using the “bad person” theory. The investigator concludes that the defendant is a “bad guy” or that he or she will not come off well during trial and, therefore, must be the perpetrator or have done something wrong. Unfortunately, this approach fails to win the hearts and minds of prosecutors, defense lawyers, and juries, and it can result in significant embarrassment for fraud professionals or forensic accountants.

What do we mean by evidence-based decision making? Critical thinking requires the investigator to “connect the dots,” taking disparate pieces of financial and nonfinancial data to tell the complete story of who, what, when, where, how, and why (if “why” can be grounded in evidence). Dots can be business and personal addresses from the Secretary of State’s office, phone numbers showing up in multiple places, patterns of data, and breaks in patterns of data. These dots help prosecutors, defense lawyers, and juries to understand the full scheme under investigation. However, to be convincing, fraud professionals or forensic accountants must ensure that the dots are grounded in evidence that is consistent with the investigators’ interpretation of that evidence. The bottom line is this: successful investigators base their conclusions, and the results of their investigations, on evidence.

Scope of the Engagement

One of the biggest challenges that new forensic accountants and fraud examiners face is limiting their work to the scope of the engagement. For most fraud allegations, the engagement is much more limited in comparison to an audit. A financial statement audit is about the fairness of the financial reports (balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows); this is a much broader scope than an investigation related to allegations of inappropriate expense disbursements, for example. Audits are conducted in compliance with generally accepted auditing standards (GAAS).

Regarding tax engagements: The AICPA’s Statements on Standards for Tax Services (SSTSs Standards Nos. 3 and 4) and Treasury Department Circular 230, Regulations Governing Practice Before the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), identify tax preparers’ responsibilities related to practice before the IRS. The responsibilities are different, for example, than those associated with the narrow allegations of missing deposits and inappropriate expense disbursements. Tax preparers’ generally are not required to search for malfeasance, as long as they have no reason to believe that the books and records, provided by the client to prepare tax returns, have been tainted.

Whether the engagement is based on allegations associated with a civil litigation claim or a tip about a fraud act, the forensic accountant or fraud examiner needs to ensure that they have a clear understanding of the concerns. These allegations or concerns define the initial scope of the engagement. The professional needs to focus on, and examine, evidence likely to help him draw conclusions regarding the allegation(s). Not surprisingly, a fraud allegation concerning a billing scheme might spread to include travel reimbursement fraud; however, the initial effort should focus on the allegation(s) asserted, while the discovery of new evidence might lead to an expanded engagement. Similarly, in a civil litigation case, the allegations are outlined in the complaint filed with the court, and are clarified or updated over time with pleadings, discovery responses, motions and disclosures. The effective forensic accountant stays focused on the allegations and works in concert with attorneys to obtain the relevant evidence and examine the claims.

The Problem of Intent: Investigations Centered on the Elements of Fraud

Although the fraud triangle helps to explain the conditions necessary for fraud to occur, to prove fraud, the investigator has to deal with the issue of intent. Intent, like all aspects of the investigation, must be grounded in the evidence. In a fraud case, the challenge is that—short of a confession by a co-conspirator or the perpetrator—evidence of intent tends to be circumstantial. Although less famous than the fraud triangle, the triangle of fraud action, also known as the elements of fraud, is critical to the investigative process, whether the engagement includes fraud or litigation issues. The elements of fraud shown in Figure 1-21 include the act (e.g., fraud act, tort, breach of contract), the concealment (hiding the act or masking it to look like something different), and the conversion (the benefit to the perpetrator).

FIGURE 1-21 The triangle of fraud action: elements of fraud

Provided that the investigator has evidence that the alleged perpetrator committed the act, benefited from that act, and concealed his or her activities, it becomes more difficult for the accused (the defendants) to argue that they did not intend to cause harm or injury. Evidence of concealment, in particular, provides some of the best evidence that the act, fraud or otherwise, was intentional. In civil litigation, especially damage claims based on torts and breach of contract, the elements of fraud remain important: for example, what evidence suggests that a tort occurred (The Act), how did the tortuous actors benefit from their action (Conversion), and how did the tortuous actors cover up their activities (Concealment).17

Evidence of the act may include that gathered by surveillance, invigilation, documentation, posting to bank accounting, missing deposits, and other physical evidence. Proof of concealment can be obtained from audits, document examination, and computer searches. Further, conversion can be documented by using public records searches, tracing cash to a perpetrator’s bank account, and indirectly using financial profiling techniques. Finally, interviewing and interrogation are important methods that can be used to supplement other forms of evidence in all three areas: the act, concealment, and conversion. There is an ongoing debate in the profession about whether tracing money to a perpetrator’s bank account is good enough evidence of conversion, or whether the investigator needs to show how the ill-begotten money was used. Although tracing the money into the hands of the perpetrator or his or her bank account is sufficient, showing how the money was used provides a more powerful case and can provide evidence of attributes of the fraud triangle, such as pressure and rationalization, and other motivations included in M.I.C.E, discussed in Chapter 2. Generally, investigators should take the investigation as far as the evidence leads.

Examples of circumstantial evidence that may indicate the act, concealment, or conversion include the timing of key transactions or activities, altered documents, concealed documents, destroyed evidence, missing documents, false statements, patterns of suspicious activity, and breaks in patterns of expected activity.

The Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (The Hypothesis-Evidence Matrix)

In most occupational fraud cases, it is unlikely that there will be direct evidence of the crime. There are rarely eyewitnesses to a fraud, and, at least at the outset of the investigation, it is unlikely that the perpetrator will come right out and confess. Therefore, a successful fraud examination may take various sources of incomplete circumstantial evidence assembled into a solid, coherent case that either proves or disproves the existence of fraud. Civil litigation, by its very nature, suggests that there are at least two competing stories, that of the plaintiff and another of the defendant. Thus, as a starting point in civil litigation, the forensic accountant normally has at least two competing hypotheses. It is incumbent on the professional to use the evidence to test each of the hypotheses, as well as others that may arise based on reasonable, objective interpretation of the evidence.

To conclude an investigation without finding all the evidence related to a case is not unusual for the fraud examiner and forensic accountant. No matter how much evidence is gathered, the fraud and forensic professional would always prefer more. In response, these professionals utilize the fraud theory approach. This is not unlike the scientist who postulates a theory based on observation and then tests it. When investigating complex frauds, the fraud theory approach is indispensable. Fraud theory begins with an assumption of what might have occurred, based on the known facts. Then that assumption is tested to determine whether it is plausible and able to be proven. The fraud theory approach involves the following steps, in the order of their occurrence:

- Gather related data/evidence.

- Analyze available data.

- Create hypotheses.

- Test the hypotheses.

- Refine and amend the hypothesis.

- Draw conclusions.

The Hypothesis-Evidence Matrix

Integral to the fraud theory approach is the analysis of competing hypotheses that are captured in a tool called the hypotheses-evidence matrix. This tool provides a means of testing alternative hypotheses in an organized, summary manner. Consider the following question drawn from the “intelligence community” between the first Gulf War, Desert Storm, and the second Gulf War, Iraqi Freedom: Given Iraq’s refusal to meet its United Nations commitments, if the United States bombs Iraqi Intelligence Headquarters, will Iraq retaliate?18 To answer the question, three hypotheses were developed:

| H1 | Iraq will not retaliate. |

| H2 | Iraq will sponsor some minor terrorist action. |

| H3 | Iraq will plan and execute a major terrorist attack, perhaps against one or more CIA installations. |

The evidence can be summarized as follows:

- Saddam’s public statements of intent not to retaliate.

- Absence of terrorist offensive during the 1991 Gulf War.

- Assumption: Iraq does not want to provoke another war with the United States.

- Increase in frequency/length of monitoring by Iraqi agents of regional radio and TV broadcasts. Iraqi embassies instructed to take increased security precautions.

Assumption: Failure to retaliate would be an unacceptable loss of face for Saddam.

Each piece of data needs to be evaluated in terms of each hypothesis as follows:

- 0 = No diagnostic value for the hypothesis