Chapter 4

Getting to Repeatability

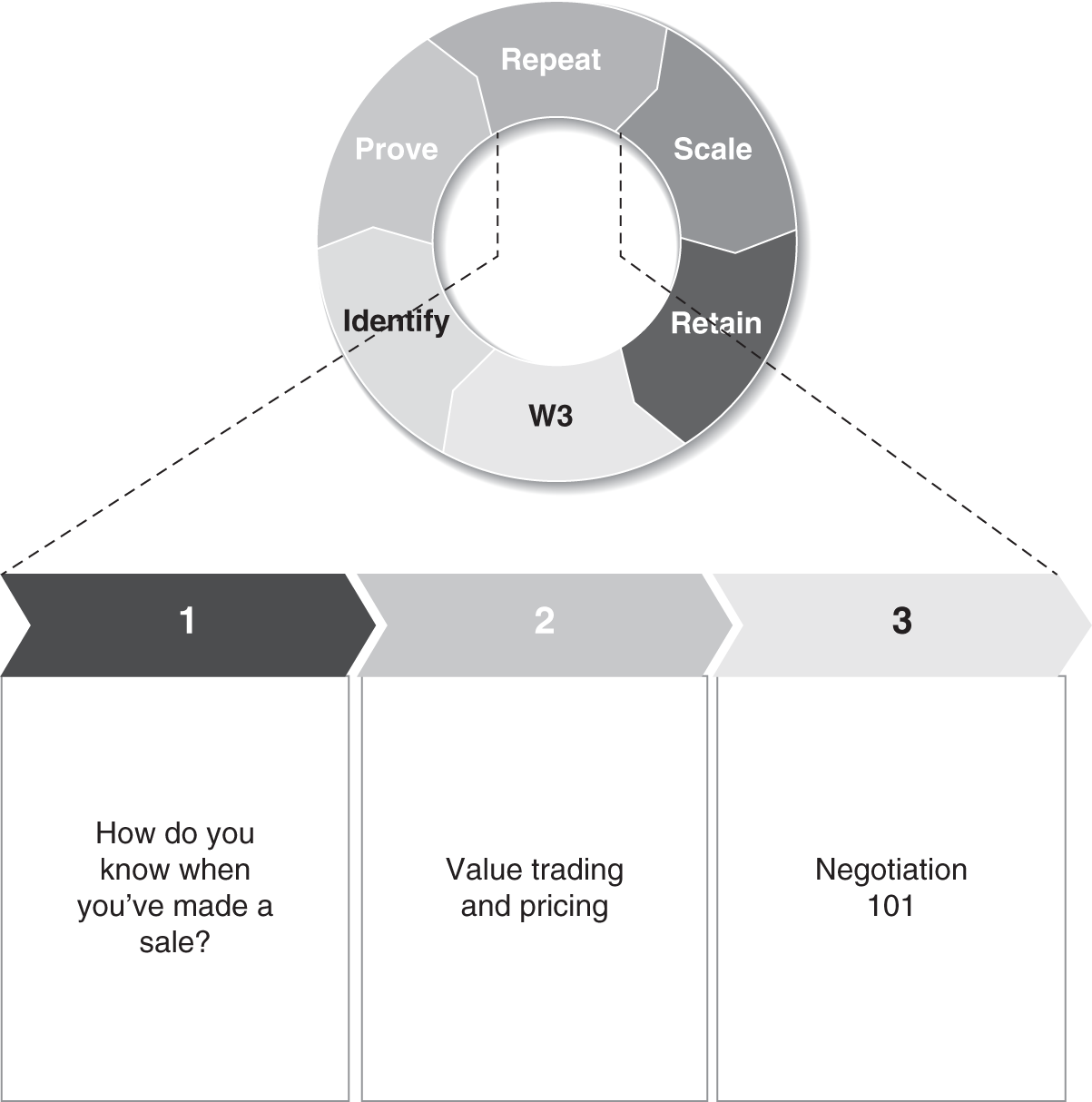

Figure 4.1 Getting to Repeatability

How Do You Know When You've Made a Sale?

By now you've identified your W3, which is to say you have a strong opinion (ideally backed up with data) on who your customer (ICP) is, what product you are selling (versus what product they are actually buying from you), and why they buy your product. With this framework, you've tested your theories in your customer development process by speaking with dozens (or more) of prospects, some of whom you've converted to customers. You've learned enough about your sales funnel that you've incorporated a CRM into your sales process, which has allowed you to start tracking and reporting on sales funnel metrics, and you've built out an early version of your sales model so that you can start tracking how the business is progressing. So what's next?

In this chapter, we look at the final piece needed before scaling your team so that you are prepared to hire and train the right type of salesperson for your company. More specifically, we will look at (a) value trading and pricing and (b) Negotiating 101, with the goal being an understanding of when you've made a sale (or not) (Figure 4.1).

To illustrate the challenges with knowing when you've made a sale versus when you think you've made one, I'm going to use an example of a company in my portfolio, Bamba Group.

The Difference between Interest and Intent

Bamba had developed some novel and proprietary technology that allowed them to reach rural residents in emerging markets (specifically Africa) who didn't yet own a smart phone. For many global businesses, Africa is a very important market. For many government and health agencies it is important to understand detailed information about the African populations. That said, reaching rural communities with limited wifi access and old technology is very difficult. Right now, the most common way to collect data from these communities is for people to go door-to-door asking questions. Aside from being extremely inefficient, this is also not always safe.

Bamba developed a technology along with very relevant telecom relationships that allowed the company to survey the rural population (many of whom use old flip-phones) by incentivizing them with mobile money and airtime. The way the product worked, Bamba would send out a survey to a small, targeted list in a rural community. The respondents would be incentivized with an offer of airtime to answer questions about their community, health, and other topics. At the end of the survey, the respondent would then get a message that if they shared the survey and the person they shared with also responded to the survey, then they would receive even more airtime. The product worked amazingly well, with the average respondent sharing the survey with over 10 more people (and the majority of those people also responding and sharing).

Bamba learned quickly that their target customer was nongovernment organizations (NGOs) and market research firms. They had no problem getting meetings and garnering a lot of interest. On the surface, it seemed like we had a potential rocketship on our hands. Bamba had two people selling, the CEO and a cofounder who focused on sales, and their meeting schedules were packed. We tested several different pricing structures and landed on a cost-per-completed-survey model, which fit this industry well, because they could budget for the amount of data they would collect. Furthermore, because Bamba's product worked so well, we were always able to collect more data than was required. We were also able to attract several great investors who equally got excited about these early indicators.

It looked like we were off to the races until we ran into two major challenges. First, NGOs worked on projects, meaning that they would have a specific initiative around data that they would be needing to capture. This one challenge caused two issues for Bamba: first, most of the time the NGO only knew about the project they were working on and had very little insight into what was coming up next. This made it very hard to create any repeatability and for Bamba to project sales. Second, project budgets were equivalent to raising funds for each project, which meant that even if the NGO wanted to use Bamba, they may not be the ultimate decision maker, based on approved budget.

This leads me to the second challenge, which was that while Bamba's solution was faster, safer, more accurate, and more efficient, it was considerably more expensive than sending a few local residents to go door to door. Because of this, oftentimes there was not enough budget to justify using Bamba, and likewise the cost for Bamba to operate didn't allow any additional margin for dropping the price.

In theory, we should have been able to reach product market fit. We had plenty of potential customers really excited about what we had built. Getting meetings was easy and keeping conversations live and active was also not an issue. We were solving a very real problem in a way that was faster, safer, more accurate, and more efficient, yet we were not closing a high percentage of business with this model. On the surface it looks like it was simply a matter of price, but in actuality it was about trading value (money for data). There was a value put on the data being collected that was lower than the cost of providing that data. Bamba did eventually triangulate and find their product–market fit and eventually sold their company to one of their primary customers.

* * *

There are a few lessons here and the one I want to really drive home with you is knowing when you really made a sale versus when you think you have made it. The cadence and volume of meetings early on gave Bamba and some early investors lots of confidence; however, where they ultimately fell down was in understanding the difference between interest and intent. There was lots of interest, but as we learned through the process, actual intent proved to be much lower, simply based on the value being traded between Bamba and their customers.

In the next couple of sections we'll dive deeper into figuring out that difference so that you can avoid the very common pitfall of “happy ears”—which is ultimately a confusion of interest and intent.

Value Trading and Pricing

Let's start with pricing. I think about pricing simply as the value you are trading with your customer. In theory it should be as simple as when you were a kid trading toys with your friends. Your friend might have had an action figure or game that you really wanted, and vice versa. If your friend asked you to make that trade you would quickly determine how much you wanted their toy compared to the toy you were about to give up. If you wanted their toy more and, likewise, they wanted your toy more, then the trade would be made. Each one of you might feel that you were getting a better deal, and in reality you both got the best deal possible, because of the perceived value you placed on each other's toys. Selling your product to your customers should be easier than this, in that the value you bring to your customer is measurable. This means that there is a clear and quantitative way for your customer (and you) to measure the value you are trading with one another.

That being said, pricing your product can be a very daunting task. How do you know where to start? How do you know if you are capturing maximum value? What if you price it too low? What will your pricing structure look like? How will your customer measure the value they receive versus the price you are charging? How are competitive products priced and how does that align with your business model? What payment terms do you start with? What are the supporting business terms, like contract length and the ability to cancel or grow? And this is just scratching the surface!

Insights on Pricing

Before you have a full-blown panic attack, let me share with you two insights I have on early pricing:

- It's Better to Undercharge (versus Overcharge) Your First Customers.

This is actually counter to what I hear a lot of mentors say and what many founders initially think. Their belief is that you should see quickly how much you can charge so that you aren't leaving money on the table and to potentially offset more cash burn. I disagree with this theory because, while you may be successful getting customers to spend more money, ultimately if you are charging more than the value they are receiving, then you end up with an unhappy customer who will likely churn. Likewise, going back and charging less later sets up a strained relationship and potentially a lack of trust from your customers, versus raising prices later, which is common.

I'm also definitely not advocating that you charge nothing. Even for early pilots I believe strongly that you should charge, because you want your customer to have financial skin in the game. What I'm suggesting is that you not be afraid to start lower than where you think you'll end up. Likewise, don't get caught up in negotiating price in the early days. There are more important things you'll want to prove before you figure out your target pricing structure (such as, can you attract customers who don't cancel when their contract is done, and what is the actual value your customers receives from your product). There are plenty of opportunities to raise prices for future customers and if you are truly providing measurable value, then you'll easily be able to raise your early customer's price later, too.

- It Will Take You a Few Years and Many Customers Before You Can Optimize Pricing.

Starting a company is a long-term commitment. In principle you already know this and this principle carries over to all aspects of your business, including optimizing pricing. Carrying on from the previous paragraph about undercharging, this doesn't mean you undercharge your first 100 or 1,000 customers, it means that you need to have the patience and discipline to spend time figuring out what your customers are willing to pay by understanding the true value you are trading with them. The more customers you have and the more time you have with those customers will unlock a deep understanding of the value (specifically financial impact) of your product for their company. As you learn more you can adjust price accordingly (ideally upwards). This just takes time, so be patient and pay attention.

Pricing Strategies

With that in mind, there are three ways you can think about pricing:

- Value-Based Pricing

This is a pricing strategy that sets prices primarily, but not exclusively, according to the perceived or estimated value of a product or service to the customer rather than according to the cost or product's historical prices. A good example of value-based pricing is your home internet. You likely have several package options to choose from, which range from very low and slow to lightning fast. Based on collective data from the market your internet company has priced each package based on that perceived value. When you purchase the package right for you, you do some quick calculations in your head to determine, based on the value trade of speed for money, which is the right package for you. It's unlikely you will want to pay more for a package you don't need if there is a cheaper option.

- Cost Plus

In this pricing strategy, the selling price is determined by adding a specific markup percentage to the product's unit cost. A good example of this is buying gas for your car. As you know, the price of gas changes often, as it is driven by public markets. Your local gas station buys and then prices the gasoline at a percentage above their purchase price. Because there are several gas stations in your neighborhood, they all need to price their product both as high as they can above their cost, but also low enough to be competitive with the other gas stations. When you go to buy gas, you are paying whatever price is asked, which can vary even from day to day. The value of that gas has not changed for you (you need to get to work and back), but the cost of that gas is based on what it cost the station to buy it plus the overhead needed for that station to keep its lights on and to show a profit.

- Wild Guessing

This is exactly what it sounds like. While I don't really recommend this, sometimes this is just where you have to start so that you can get a baseline. This is usually the tactic you use when you have a new product in a new market and you simply don't know where to start. Inherently there are aspects of cost-plus and value-based pricing when you use this “method,” but it's really just you trying to rationalize why you believe a customer will pay a certain amount. If you do find yourself needing to just guess at a starting point, my recommendation is to very quickly try to understand the value your customer is actually receiving in the trade so that you can gather enough data to move to one of the other methods.

And guess what, it doesn't really matter which pricing method you ultimately choose, because regardless of your product or company or market, the customer will never pay more (for long) than the fair value they believe they are trading. That being said, I personally always strive for value-based pricing from day one. This doesn't mean asking your prospect what they think they are willing to pay but instead involves a more intricate line of questioning so that you can determine the true value of your product for your customer, which they, in turn, validate for you.

Let me repeat that in different words: you need to figure out enough about your prospect's business and pain through questioning, and then provide that back to them with how your product will help make or save them money (either directly or through time/hiring) and then have them validate that value.

Pricing is tricky in established categories, exponentially more so if you are pioneering a product in a new category where your buyer may not fully appreciate the value relative to the pain you are solving. You need to prove a 10-times cost savings ROI on your product or, even better, show a direct link to revenue lift.

The challenge here is that direct attribution is very tough to prove unless you have a deep understanding of your prospect's business and how your product directly saves money or lifts their revenue. This requires asking probing questions about value, questions your prospect may have never considered. And that requires you to be a student of their business. You need to deeply understand who your customer is, what they are buying from you, and why they are buying it.

—Rob Taylor, cofounder and CEO of Convey

Optimizing Trade in Value and Pricing

My favorite personal example of optimizing trade in value and pricing was at BlackLocus, where after a handful of customers were onboarded, one of my team members built out a simple (but very powerful) return-on-investment (ROI) calculator. In reality it was too early for us to really understand the full-value trade we were having with our customers, but we were starting to see and collect trends around how they perceived our product to affect both top-line revenue as well as margin contribution. At this point, by using the W3 framework, we clearly identified our target customers as online retailers whose revenue was over $100 million a year and had a centralized pricing strategy with a single person being the decision maker on pricing. We also learned that for most of our customers, less than 20% of products made up greater than 80% of their revenue (and hence, where they focused their time and effort). Furthermore, in those 20% of products, our customers typically had a good understanding of how those products sold from a volume perspective and were able to project sales, revenue, and margins with decent accuracy. They became attracted to working with BlackLocus because it provided more data and transparency into the market, which turned their “decent accuracy” into high accuracy, which increased revenue and margin.

The calculator had inputs, which were assumptions on our prospect's business, as well as (data-driven) inputs on how we expected our product to impact their business, based on what we've seen with our existing customers. We'd share the calculator with our prospects (over video calls or in person), knowing that while we had some good initial data, we still had a lot to learn. We would let the prospect play around with all the inputs relative to the price we were suggesting so that they could see how their ROI would be affected by working with us. Once the value trade was clear (and for BlackLocus it was always clearly a good value), assuming we were talking to the decision maker, we'd always get a verbal commitment in that meeting. And if we weren't talking to the right person, we now armed our contact with the information they needed to take to their boss and ultimately become a customer.

Understanding the value that is being traded between you and your customer is the ultimate key in pricing your product and maximizing the “mutual” value that both of you provide and are paid for your product—and ultimately optimizing revenue. When you are first starting out, knowing where to start will feel like a bear of a task to tackle and the stress related with “getting it right” can sometimes be overwhelming. My hope in this section is to relieve some of that stress by giving you the comfort in knowing it's okay to price low to start as well as preparing you to be okay with it taking a long time before you optimize pricing. Along the way, you'll likely get advice and even pushback on these two concepts. “You aren't charging enough or you aren't moving fast enough” is what you'll hear and you might even feel that way yourself. That's the time to step back and spend time digging into what you know and what you still have to learn about how the value is being traded between you and your customer.

Negotiation 101

In the last section we talked about pricing and value trading. The more you understand about the value being traded between you and your customer, the easier any pricing negotiation will become. This is because if you know the value you provide to your customer relative to any competitors, and your customer believes that the value they are trading is the “best deal they can get,” then, assuming they actually need your product, the odds are weighted heavily in your favor that they will work with you no matter how much they try to negotiate price with you.

There have been more (great) books written about negotiating than most of us will ever read. Rather than simply repeat what others have said, my intention in this next part is to share with you my personal style of negotiation, which is: I don't.

That doesn't mean that some parts of a deal won't change and move around. In fact, it's the opposite: some parts will almost always move around (especially in a complex or enterprise sale). For me, it means that up front I set a tone of full transparency and drive the conversation around data versus emotions when talking about which points are not negotiable and which are less important.

For example, while price is a factor, it may be more important that we have a 12-month term. It may be important that we can reference the customer or it may be a requirement for the customer to meet with us monthly for feedback. Whatever the case may be, up front I always do my best to tell the prospect what points are important to me, why they are important, and where they need to be. This helps to set the stage for a very open “negotiation” process in which, rather than battling point for point on deal points, you begin to work together as a team to get the sale closed.

For example, if you know you are at your best price (which is where I always strive to start and finish), then I say up front “If this doesn't work, then we should both move on.” Most people are looking for the best deal, and that is fair. Once they feel like they have the best deal (which is what you are saying) then you can focus on the rest of the deal mechanics (term, payment terms, legalese, etc.). Likewise, I also make it a point to understand, as part of the sales process, what is important for my prospect's process in the same way. Is price a factor and to what degree? Do they want any special concessions if they are an early customer? Are there payment terms they need? And, most important, how will they be measuring the success of this relationship?

I'm going to digress on that last point for just a second. In reality, how they will measure success is not likely to be an actual part of the formal deal you are making. That said, by understanding what they see as success, and how they will be measuring it will allow you to better understand the value they believe they are trading, and sets you up to make sure that you are meeting their expectations (and if you are not, this should give you the ability to get ahead of why, so that you can understand how to fix it).

Working Together to Reach a Deal

Early on, I spend most of my energy on making sure critical deal points are aligned and, if not, whether they can be. If a deal can't be reached, we walk away (if you are running a great sales process, you will know this long before you get to the final stages). Assuming both parties want to get the deal done, then it's simply a matter of working together (not as opponents) to get to a deal that everyone is happy with. I believe this is one of the most critical factors in closing sales, especially complex ones. If you and your customer negotiate as opposing players, it's much harder to work through areas of disagreement or misalignment. If you are acting as partners, then you are more apt to work together to find creative solutions for any challenging deal points.

View Your Prospect as a Partner

There are two things that I try to always do when negotiating with a prospect, or maybe better said, when working on getting a deal done. It starts with this simple visual—picture yourself and your prospect sitting on the same side of the table in a meeting. This simple visual helps to orient you to working together as a team rather than against one another. In this case, you are clearly only half the equation, but what this creates in our mind and action is the ability to approach your prospect as your partner. If you try it, what you'll notice is that your language and posture changes as you begin to work with your prospect. If you are truly visualizing yourself as being on the same side of the table and working together, it will be much easier to listen and be additive, rather than combative. If you can maintain this visualization, then your prospect will eventually match the feeling, because they will feel supported and trusted.

Take Emotion Out of the Equation

The second thing I do is to continuously remind myself to take any and all emotion out of the conversation. This doesn't mean you can't be high energy and enthusiastic—you should always be yourself. What it means is that I continually remind myself that this is not personal, it's business, and ultimately everyone is trying to do the best possible job. Candidly, I'm a pretty high energy and emotional person. It has literally taken me 20 years to feel like I'm mastering this, and yet I still get caught up here from time to time. It's hard because we all care so deeply about what we are doing. I will sometimes need to remind myself several times in a single conversation to curtail my emotional reactions and stick to the data to get the deal done—which often means letting your ego go.

I've negotiated hundreds (if not thousands) of things in my life and as I've become more competent at staying level-headed and data driven, I've seen a direct correlation with accomplishing more successful deals (or knowing much sooner when to walk away). Maybe more important, it's allowed me to control the conversation in terms of always getting to truth. The most extreme example of this is when I'm negotiating with a relatively irrational person who is also emotionally driven. Sometimes that is a deliberate negotiating tactic and sometimes it's just that person's personality. In either case, they are looking to create an emotional argument, either because they don't have the data or don't understand the data to make a good decision. When I don't match their emotion, keep it data driven, and spend time trying to understand the motivation behind their reaction, it gives me the ability to listen and see if we can get to the root of what they really want to accomplish.

I want you to keep in mind that some deals just won't get done, because the value being traded between you and your customer doesn't seem fair to one of you. The key to getting any deal done is understanding what your prospect (really) needs and making sure you are clear on what is important to you. Keeping your own emotions in check greatly increases your chances of that deeper understanding and ultimately making a sale.

The Process of Making a Deal

So how does this manifest into actually working with your prospect and making a sale?

Start with a Conversation

First and foremost, and I cannot stress this enough, never negotiate over email. Email should be used for setting up meetings, clarifying points, recapping meetings, and sending documents. Email should never, ever be used for closing a sale. In this section we're focused on negotiating, which starts with the proposal. Always get on the phone or arrange a video call and walk your prospect through the proposal. Explain points that you think are important or that could be complicated. Let them ask questions and have a conversation. Then and only then should you send a proposal over. And the same goes for any major (and ideally minor) point you are negotiating around.

There are a couple of ways in which I try to always accomplish this. The first is that, whenever possible (and realistic due to finances, cost of the product, etc.) I try to have the big conversations in person. Not only do I try to do them in person, but I request that we meet in a small meeting room where we can sit next to each other (not across the table from each other). Remember what I said before about visualizing working next to each other at a table; well, this is your chance to use that visualization, and when you are both in that small room, it's likely that your prospect will be in a similar mindset. Sometimes this is hard to coordinate, especially when you travel to them. I will typically try to let my prospect sit first and then say, “Hey, I'm going to sit next to you so that we can work on this together more easily.” Very few people will reject this idea, and if you do it casually and sincerely enough it won't be awkward but instead it will set the tone for collaborating as a team.

Often meeting in person isn't an option. My next go-to is always a video call. While technically you are still sitting “across” from each other, you are able to see one another, which helps to gauge intent and emotion, and makes the meeting into a conversation between two real people.

Having these conversations over the phone is always my third option and is still preferable to email. Since talking on the phone can lack a personal feel, it becomes even more important to continually visualize yourself sitting next to each other at a table, and likewise to continuously remind yourself to leave the emotion out of the conversation. Even though I always strive for in-person or video calls, I'd guess that better than 50% of my negotiations still happen over the phone. Even if my contact emails me, unless it's something we are simply agreeing to, I'll pick up the phone and call them in return. In my experience, a five-minute phone call can almost always get you to truth faster and with much less drama.

Be Truthful and Transparent

Whenever I'm “negotiating” or working with a prospect to get a deal for the first time, they are always a bit thrown off, confused at first, and sometimes maybe even a tiny bit frustrated. This is because most people think about negotiating as going over deal points in detail, point for point, and specifying prices and terms. In my experience very few people, much less salespeople, negotiate by not negotiating. Typically each side will posture a bit or will hold some information back. They will usually also assume that the other person is doing the same. They will assume that you have wiggle room and that you are trying to take advantage of them—this is why you often hear people say “I hate salespeople.” Guess what, I hate those types of salespeople, too, which is why I've worked very hard over the past 25 years to always be truthful and transparent. Because of this, I feel like I've been very successful in closing the most important sales in a way where everyone feels like each side got the best deal they could get. This strategy has always helped in getting a sale closed because my prospect quickly learns that I'm honest and working with them (not against them) to create the fairest trade possible for all parties.

I also realize this style doesn't work for everyone, but if you are going to try it, the most important thing to remember is that everything you say must be 100% fully transparent. If you can build that honesty muscle, you will find that every deal, which should close will. Likewise, deals that ultimately shouldn't be closed, won't be closed. This is a good thing, because when you close the wrong customers you end up spending more time with unhappy people and ultimately will have churn.

Knowing When the Deal Is Ready to Close

The final point I'll touch on in this part is “How will I know when the sale is done?”

First off, and to be very clear, you have not closed a sale until a written agreement has been signed. This means that all business and legal points have been agreed upon. This includes price, term of the agreement, and payment terms. Not only is it very clear how long your customer will be paying you, what the amount is, and when, but there will be legal paperwork (contract, agreement, purchase order) that you both have signed. This makes the agreement legally binding and official. Until that point, any deal can fall through, regardless of intent. You should not celebrate until both contracts are signed (and ideally money is in the bank).

That being said, there are a few clear indicators when those two things are most likely going to happen. The caution here is to beware of “happy ears.” This is when you think your prospect is ready to buy because you are an optimistic entrepreneur or salesperson and think you are hearing all the right signals.

To avoid happy ears, let's go back to your sales process and the negotiations. You can create a checklist of the items you've learned along the way that says, as you go from stage to stage, that certain things need to happen. Put this list in your CRM. For example, do you have verbal acknowledgment from the actual decision maker who can approve the budget? Have you already agreed on a price, term, and payment terms? Do you have a start date and onboarding plan in place? If there is a technical implementation, is that team on board and knows that this is coming? If you are selling to enterprise companies, you may also have to go through a procurement process. We won't cover procurement in this book, but if you aren't familiar, procurement is a separate division of an enterprise company whose entire job is to make sure that before any money gets spent, there is a “second set of eyes” to go over the deal and legal points. Procurement can be a beast and will often kill deals. It's not uncommon for you and your contact to be in full agreement and then for procurement to come in and try to renegotiate everything. In these cases it's even more important for you and your contact to be in full agreement about the relationship, so that your contact can (and should) be working with you to get through procurement. If you are ever selling to enterprises, one of your first questions should be about their procurement process, so that you can start preparing early.

If any box is not checked, then that is a weakness in your ability to close the sale, and when all the boxes are checked, then you will know that 90% of the time (or even more, barring an act of nature), your sale will close. Similar to your sales process, early on you just have to make an educated guess on this checklist. Over time, you should be revisiting that checklist and comparing it to your data to refine it. Once you are in scale mode, you should have greater than 95% confidence in that being the final checklist, so that your sales team can just go through their process, check off the items that get them closer to closing each deal, and ultimately close the sale.