Chapter 2

Finding Your First Customers

Figure 2.1 Find Your First Customers

Over 20 years of taking new technology to market and working across startups, like Bazaarvoice and Convey, focused on acquiring customers across many different markets, the simple axiom of “know thy customer” rings truer to me now more than ever.

I have been on both sides of this, having a lot of early customer acquisition success with early adopters and then scaling to the next wave of customers too early. Without doing the really hard, roll your sleeves up, work of asking the fundamental questions about the customer's struggle, why it matters and what business pain it is attached to, it is nearly impossible to calculate meaningful ROI that they are willing to pay for.

I believe what drives us to want to move fast and to shortcut this critical process is #1 the fear that our window of opportunity to be first will collapse and competitors will move in quickly, and #2 that somehow simplifying the proposition too much and narrowing too far will diminish the value of the offering.

Real immersion in your customer's struggle is the key. At this vital step in the journey your early adopters are willing to engage in helping you to articulate and clearly define a pain, challenge, or opportunity (PCO) that is not widely known or recognized. They believe that solving the problem will translate to out-sized results and will make them look like a superstar innovator and performer to their company and peers.

You can't move into selling in a repeatable, at scale way until this PCO has been fleshed out, well documented and publicized in a way that the broader, early majority market can begin to raise their hand and identify with it.

A real risk here is that effective early stage salespeople can sell past these shortcuts and at least for some period of time show strong customer acquisition among early adopters. The result is the painful discovery two years into the journey that you have hit a scaling wall because you haven't taken the time to do that hard work to truly understand the business you're in. Fixing it at that point can be extremely daunting if it's even possible because you are effectively starting over.

—Chris Richter, VP of revenue at Convey

The W3 Framework Is Worthless … Until You Test It!

In Chapter 1 we used the W3 framework to identify the who, what, and why: that is, who do we believe our customer is, what are they buying from us, and why does our product meet their needs. We do this on the quest to achieve what every company is ultimately looking for, product–market fit. If you aren't familiar with this concept, then I implore you to get very familiar with it, because without it you don't have a sustainable company. Product–market fit is the degree to which a product satisfies a strong market demand. In other words, if your product doesn't fit your market, you will have no demand and therefore no business. We cover this in greater detail further on in this chapter.

In this chapter we will take the W3 work from the Chapter 1 test and prove it, in the real world, through the customer development process, with the goal of identifying our ICP (ideal customer profile) and early signs of product–market fit (which I define as product–market direction; Figure 2.1). Going out and testing this work, collecting data on why you are right (or not) is imperative before you attempt to scale your sales organization.

There is a very common error I see here, especially among first-time founders, which is that once they feel like they can describe even partial aspects of W3, they think they are ready to start hiring several salespeople and start scaling revenue. This is actually where you need to pause and go try to prove why your theory on your W3 is correct. While this may, on the surface, feel like slowing down the train, there are a few reasons this is crucial to actually selling more faster, starting with the fact that it reduces the chance that you are wrong after you've hired a bunch of people and are far down a particular customer path. It also gives you data that will inform the sales process (we discuss this more in Chapter 3) and finally, it'll provide more data (and confidence) to investors, which should lead to greater funding and ability to scale faster.

Before we get into the work part of this chapter, I'd like to share one personal example to help set context for why the customer development process is so important.

The Wrong W3

I joined BlackLocus in early 2012 as head of sales. BlackLocus sold competitive pricing and assortment analytics to online retailers. What this meant was that we could tell a retailer (1) who their competitors were, (2) how their products were priced relative to their competitors, (3) what products they sold that their competitors did not sell, and (4) what products they did not sell that their competitors did sell. In theory, anyone with an online retail presence could use our product. It didn't really matter if you were selling dog beds, hammers, shoes, or vitamins. If the product had a decent description, we'd be able to identify our customers' competitors anywhere on the web.

When I joined the company they had already hired a seasoned and good, later-stage, salesperson (we'll call him John). John had closed roughly 15 customers when I joined. As my first task, I tried to determine our W3. After speaking with John, some customers, our CEO, and our head of product, it was still unclear to me who our ideal customer was, what the customer was buying, or why they needed our product.

Up to that point, John believed he should be able to sell to anyone with an online retail presence because the value proposition (being able to tell our customers how their products were priced relative to their competitors) was relatively similar and by itself should persist. While John did a good job closing several early customers, BlackLocus was caught in a vicious cycle of (many) unhappy customers who were churning as fast as John was acquiring new ones.

The cycle was that John would spend time and resources selling a customer and getting them to believe our ability, only to result in that customer leaving a few months later. Our revenue wasn't shrinking or growing, it was simply not moving, because John was replacing customers at the same rate we were losing them. We didn't have a clear picture of our who, we didn't really understand what are customers were buying (only what we were selling), and therefore no idea why customers were buying. The customer profiles were all over the map, making it impossible to triangulate on what or why they were buying (or not buying).

Defining BlackLocus's W3

When I joined, I didn't have a strong opinion of our W3. I understood what we were selling, but I wasn't really sure what our customers were buying and therefore had no idea why they bought (or how they would measure success). I spent the first three months questioning everything and talking to both existing and potential customers of all sizes, industries, experience level, location, and so on. I even went outside the retail world simply to try and disprove our theory about our e-commerce focus. You can see, at the end of this chapter, examples of the types of things you can question (by which I mean everything).

In that three months I was able to narrow down our W3 and define it clearly as “large retailers with over $50 million in revenue who had a strong online presence.” Taking it further, I learned that our customers should be retailers whose products were hard goods and often commodity items like drills, hammers, electronics, and so on. This could range from home improvement chains to big electronics chains, as well as bigger retailers who sold branded items where a SKU number was used across all retailers. The reason we learned this was because commodity items and typically hard goods are clearly defined and easy to identify, making the competitor sets easier to identify. Additionally, they typically have tighter margins for our customers, which makes them higher priority. These aspects combined made our impact on their businesses bigger and easier to measure.

Finally, I learned that if the company didn't have a role whose job was specifically focused on pricing analytics, then the likelihood of a successful sale or implementation became dramatically decreased.

There are two primary reasons why this became an important characteristic. First, when a company centralized their pricing efforts, it demonstrated that the company put a high value on optimizing price and margins, and second, by centralizing their pricing efforts I now had one main buyer versus a decentralized model where there would be many people that we would need to convince that we could do an aspect of their job faster and with more accuracy. The fact that I had fewer people to sell to and the importance the organization put on the effort could decrease the time to close by six months or more!

Let me describe to you the difference.

- Centralized pricing efforts: When a company centralized their pricing efforts, it meant a few things. First and foremost, there was one person (or department) responsible for all pricing decisions. This was important for us because it meant fewer people whom we had to convince that BlackLocus would save them time and make them more money. It also meant that they likely used data, in some form, to make pricing decisions. Sometimes this would be a complex algorithm around self-identified products and competitors, and sometimes it was as simple as a person managing a spreadsheet. In any case, it demonstrated to us that the company believed data (not intuition) was better for driving pricing decisions. Finally, and maybe most important, our observation was that companies who had a centralized pricing function were typically more tech-forward in general and looking for scale efficiency—which was at the core of what our product promised to deliver.

- Decentralized pricing efforts: When a company had a decentralized pricing strategy it usually meant that the buyers or merchandising team would make pricing decisions individually for the product lines they were responsible for. In a big retailer there could be dozens or even hundreds of buyers. Right off the bat, this made the idea of selling a much bigger challenge. Can you imagine if you had to get buy-in from 50 or more people to sell one single customer? Additionally, while some of the people making pricing decisions at these retailers did use some form of technology (even if just to track pricing changes with their products), our observation was that these retailers typically thought that some of their competitive advantage was the individual buyer's or merchandiser's expertise. Right or wrong, inherently in that line of thinking was a rejection that any company (BlackLocus or any of our competitors) would ever do their job better than them. The uphill battle of trying to convince dozens or more people whose initial reaction was that we could not do their job better seemed silly, and therefore we tried to stay away from those retailers.

Next I learned what our customers wanted and were buying, which was “competitive insights” for their highest valued/velocity items. This was different than what we were selling (pricing analytics for their entire catalogue) and while the product was mostly the same it provided how we should be pitching BlackLocus.

Next, understanding the who and what lead me to the why, which was at a macro level almost always the same (to price competitively against competitors), but almost always varied from a single competitor, a series of competitors, or in some cases just Amazon.

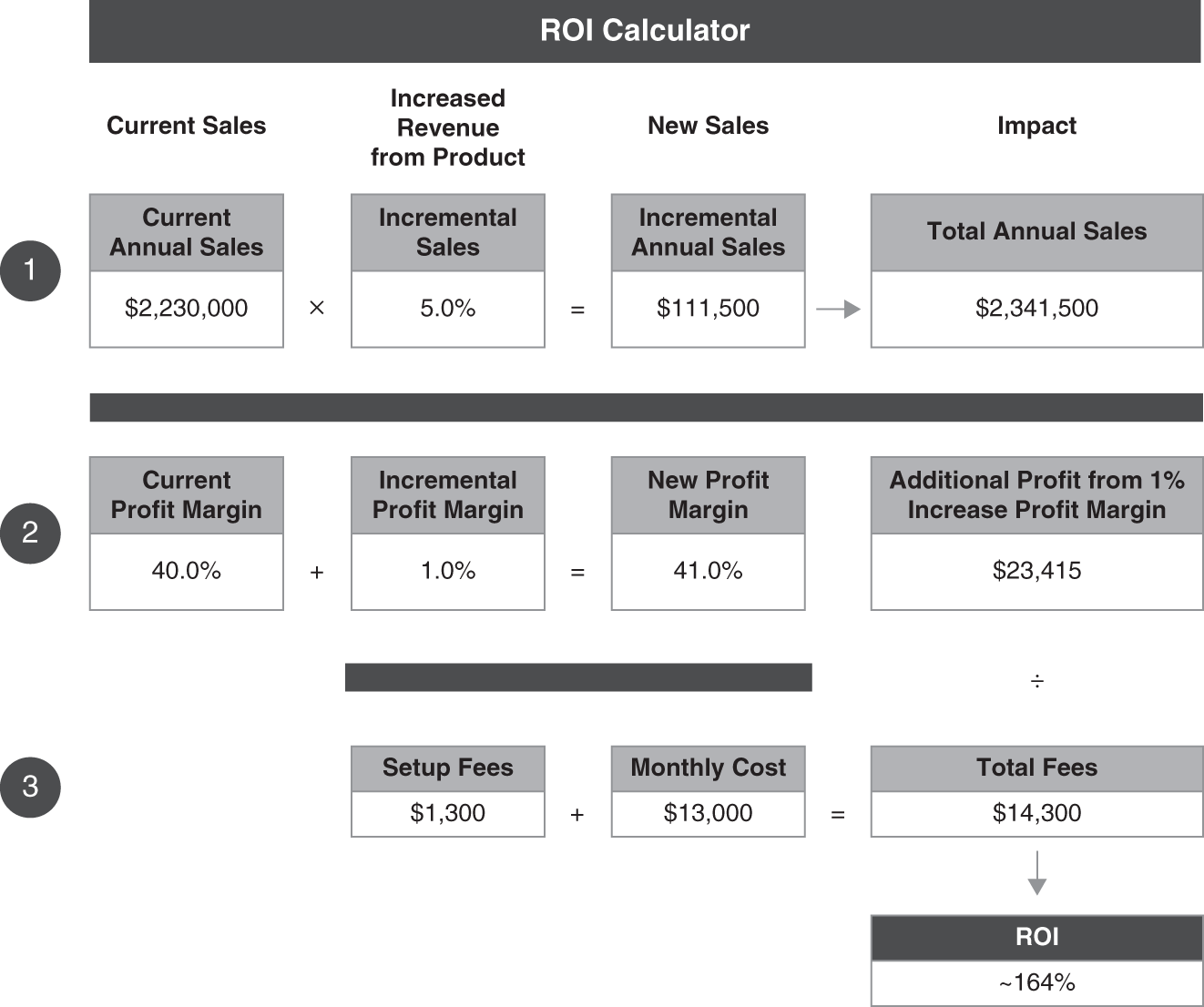

Measuring Value with an ROI Calculator

Understanding the why also gave me the ability to develop a system to measure value transfer, so that our customers (and we) would understand the direct monetary impact to their business. This system was a one-two punch. First was the development of our ROI calculator (Figure 2.2). The ROI calculator took into account both the potential revenue increases to their business as well as margin increases and operation efficiencies resulting from using BlackLocus.

Figure 2.2 ROI Calculator

Source: Courtesy of Austin Dressen.

The calculator was a series of formulas where the company's variables (number of products, pricing changes, increase in sales, and margin contribution) could all be tinkered with, giving our customer a clear idea of how their business could be affected if they worked with us and what the return on investment (ROI) would be to them.

The second part of the one-two punch was that we made the ROI calculator a part of the sales process. Once we identified a need with a prospective customer (and the customer acknowledged there could be a fit), the next step would be to share the calculator and work with our prospective customer in filling in all the variables. We already had confidence in our product's ability to work, and the calculator would let us all get on the same page about how well it would work. Once the prospective customer saw how BlackLocus would impact their business, we knew the sale was inevitable.

Now, there were a handful of cases where the ROI calculator showed minimal or no real impact to a retailer. In these cases, this was also a huge win because we knew then that this wasn't a good long-term customer, so we'd walk away. While this didn't happen very often, cases where it did happen usually meant that the customer didn't sell a lot of products and the products they did sell had such a small margin that there simply wasn't enough volume of data to have a meaningful impact.

Knowing this was also great because we wouldn't waste any additional time or resources on a customer who wasn't a good fit for our business. Not all revenue is good revenue, and knowing when to walk away from a sale is equally as important as knowing when not to.

At the point when we figured this out, our revenue was roughly $10,000 in monthly recurring revenue (MRR). Within six months our revenue jumped to over $120,000 in MRR because we knew exactly who to sell to, what they were buying, and how to articulate the value to their business. In our case, we nailed the ICP so quickly and directly that in less than a year after identifying our ICP we sold the company to Home Depot for over $50 million on less than $1.5 million in annual revenue.

Lessons Learned

A few things I want to point out specific to going through a customer development cycle:

- Three months felt long. The company's CEO and board were initially concerned about halting growth. They were worried that taking the time to step back and prove (or in this case disprove) the initial theory on their W3 would slow down revenue plans. As I hope this story points out, taking the time to define and prove our W3 actually did help us to sell more faster.

- Three months was short, actually, and we listened well. What I mean here is that, had we instead kept with the initial plan, while we would have potentially increased revenue, we would have stayed in that vicious cycle of sell-churn-sell-churn. It's hard to say how long the customer development process will take—it could be three months or it could be much longer, though it's rarely much shorter, simply because you need time to collect enough data to prove/disprove your theory. By listening well, I mean that we took the time to ask lots of question, collect data from our targets, and then test our theories to confirm we understood what our customers were saying.

- Had we not gone through this process, we would have continued to sell small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) and had high churn, low revenue, and no exit.

* * *

A common pitfall here, especially with early sales, is that you get a few prospects to say “yes” and pay you. You may close 5, 10, or more customers (depending on the potential size of your ICP pool) so you start ramping sales. This is the time to stop and question everything. Confirmation bias, which is defined as the tendency to search for answers that confirm our hypothesis, can be one of the most dangerous things for a sales team—your job at this point is to disprove that your ICP theory is correct! Once you start seeing some real traction, it's time to go back to your theory and ask yourself why you might be wrong, to see if you can disprove it and/or find limitations.

If you can't disprove your theory, then you have directional indicators of product–market fit and are ready to test scaling your sales team. If you are a business-to-customer (B2C) company, the same principles apply. You may get really good at bringing people to your site or downloading your app, but then usage falls or the value your users find in your product is much different than you believed it would be. B2C is only more complicated in that you'll need to spend more time understanding in-depth dynamics of usage and repeat-usage to truly nail your ideal customer profile (ICP).

All too often founders reject this idea. They believe that by limiting their ICP early on or questioning early positive signals, they will limit their full potential and/or ability to scale quickly. I've personally been here dozens of times, both directly and indirectly through my personal investments, and my experience says the opposite, which is that maniacally focusing on identifying and proving your ICP is crucial in scaling long-term customers and building a sustainable business.

Sales versus Customer Development

When we first entered Techstars we thought we had a strong idea of our ICP, but what we learned was that it was too broad. We took a small step back and ran a customer development process, which lead to us clearly proving our ICP which has resulted in skyrocketing sales.

—Kurt Rathmann, founder and CEO of ScaleFactor

So what does all this have to do with the difference between sales and customer development? The next step in building a highly scalable sales organization is to prove (with data) your W3 theory through the customer development process. To do this, it's first important to understand the difference between sales and customer development. This is an important distinction and until you've gone through at least one full customer development cycle (and likely more) to largely prove your theory, you are not ready to start selling at scale.

Let me say that again, slightly differently to drive home the point—stop selling! You aren't ready. First, by using the customer development process, prove why you are correct in your theory of your W3.

Here is how we will define the two:

- Sales: We all know what sales is—it's exchanging money for goods or services. The kid with the lemonade stand and the founder with the multimillion-dollar medical device are doing the same thing: trying to convince you to pull out your wallet and exchange your money for their product. And Webster's dictionary defines “sales” as the exchange of goods or services for an amount of money or its equivalent.

- Customer development is not a well-known term and there are a lot of definitions of what “customer development” means. The definition I like best is by Steve Blank, attributed with creating the customer development concept, the practice of gaining customer insights to generate, test, and optimize ideas for products and services through interviews and structured experiments.

I would add to Steve's definition one element that I believe is crucial, which is getting people to exchange real value (and ideally pay) for early versions of your product (even if your product is still your minimum viable product [MVP]). Yes, you read that correctly, even if your product is in its most basic and minimum form, simply hearing someone say they would want it is not enough proof for you to claim product–market fit. Your customers, even your earliest customers, need to put their money where their mouth is. This means that before you let them use your product and become a customer, they need to pay you something for it. Ideally that is money, but at minimum there should be some sort of ongoing time commitment from the customer that demonstrates both their desire for continued use of your product and in the best cases their willingness to help you improve the product they are using. The reason this is critical is because it's really easy for anyone to offer up ideas (even great ones) but until someone is willing to exchange value (money, time, or information) there is no proof they or anyone else will.

Your company is not ready to go from customer development into sales until you clearly know your W3 and it's been largely proven through the customer development process with data to back it up. You must have strong conviction with proof of who your customer is (also known as ICP), what they are buying, and why they are buying it. Additionally, you (and your customers) should have a well-defined and repeatable understanding and way to measure the value transfer.

In its simplest form, this “value transfer” can be explained as both you and your customer feeling like the trade between your product and the money they pay you to use it is reasonable. Your customer ideally has a way to measure the value they receive from your product relative to what they are paying you (and it should be a positive ROI for them). Likewise, you believe that the money you are receiving from them is both fair and, more important, covers the expense of running your business, ideally with healthy margins.

I do want to make a very important note here, which is that early on, especially when you are in customer development mode, it's likely that you are underpriced and that your customer is getting greater value from your product than what you are charging them for. My personal philosophy here is that is normal and expected—and that you won't find true price elasticity until your business is much more mature. If you try optimizing for (a higher) price too early on, you'll run the risk of getting false negatives and hearing no from real potential customers. I believe it's better to undercharge early customers so that (i) you know they are willing to pay something ongoing and (ii) lower the barrier for your early customers who say yes. Assuming your product delivers high value, finding the right balance for price can be tackled later. We will cover this in greater depth in Chapter 4.

Once you have this proof, you are ready to build and scale your sales team. Until then you are in customer development mode.

For me, pivoting is justified in two situations: (1) lack of Value-Market-Fit, where what you are pitching (value) does not resonate (regardless of if the product is quite to the point of sustaining true customer “happiness”). Think of Value-Market-Fit as being able to walk in and close 9/10 customers. (2) If you found this fit, but the opportunity size (Total Addressable Market), is not large enough to support the size of business you are trying to create.

When we entered Techstars we were focused on chasing the metrics of revenue and growth after some early traction and hiring a few salespeople, without paying attention to whether we had achieved VMF. This led to churn, unsustainable customer growth, and issues with sales funnel metrics.

When we finally stepped back and honed in on finding the core value in our offering, we were able to refocus and find repeatable success with our pitch to our target personas. Knowing that while our product might not be there yet, we knew the value we were building was sustainable gave us a foundation to build from. As founder, I had to be the one to figure this out; I hired sales too early and delayed this realization. The key was being honest with ourselves and looking deeply at whether the signals we were tracking and the traction we were getting was actually an indicator of a market fit or just early revenue.

—Noah Spirakus, CEO and founder, Prospectify

Another reason this distinction is important is around hiring. The profile of someone who does sales versus someone who does customer development is pretty different. We'll spend more time on hiring in Chapter 5, but here are a couple of quick differences between the two.

Salespeople

- Need and sell much more when they have a defined customer profile. A true salesperson can sell anything to almost anyone, but that is often not what's best for the business. This is the who in W3.

- Need a defined sales process.

- Need pricing (or at least pricing parameters) to be defined. There is a known business model and pricing structure.

- Compensation is typically commission driven and title sensitive. A typical salesperson earns a base salary and the majority of their pay comes from commissions (receiving some percentage of the sale, once closed). Salespeople typically expect traditional hierarchical titles like account executive, sales manager, VP of sales, etc.

- Asks lots of questions focused on closing deals.

- Will close all business possible regardless of value fit. Going back to our BlackLocus example, our original salesperson John was closing any business he could find without regard for customer fit. He did a great job of closing new business, but because those customers were not right for BlackLocus, many of them churned.

Customer Development People

- Help identify and define the customer profiles.

- Help identify and define the sales process.

- Help figure out and define pricing.

- Compensation is typically base salary with an annual bonus tied to company performance.

- Rarely title sensitive.

- Ask lots of questions focused on understanding value transfer and understanding customer needs.

- Be willing to walk away from prospects when there isn't a clear value fit.

How to Find Your ICP (Ideal Customer Profile)

In Chapter 1 we discussed W3 and spent time on who. We developed a theory of the characteristics of our who and eventually put together a list of our top prospects. Now we're going to go out and see if we are right. Once we have strong conviction that our who is correct, we'll call that our ideal customer profile or ICP. And once we are confident in our ICP, we are one step closer to being able to scale our sales organization and revenues.

But before we get there, we need to prove, or at least get strong conviction, of our identification of our ICP. And I want to warn you that, while this work can feel a bit tedious, the risks associated with not going through this process can kill your business before you even get started.

Here is a short story from one of my portfolio companies to help illustrate the point. I invited Monica Landers to join Techstars Austin in 2016 with her company Authors.me (now called Storyfit). I knew from the moment I met Monica that she was an incredible CEO and had a great shot at building an awesome company.

A Story of Searching for Your Who

At the time, Authors.me was a marketplace for aspiring authors to post their work and for publishers to find new authors to publish. What made Authors.me special was the data science they developed so that they were able to tell an aspiring author exactly what that author needed to do, in the editing process, to develop a book that their target publisher was likely to like and publish.

Likewise, the product was able to deliver to publishers only books that fit the attributes of the books they were looking to publish, along with predictive data on how well the book would do. The real secret sauce and the actual product here was the data science. Monica and her team came out of Demand Media where they had developed similar types of technology to figure out what short form content they should publish on various websites. They knew the problem well and how to solve it and they had a strong conviction around who needed their product, writers, and publishers.

At this time they were charging both writers and publishers to be on the Authors.me platform. Writers paid a small fee to list their work and could pay an upcharge to acquire data on how they should edit their work to satisfy their target publishers. Publishers on the other hand were charged access to the marketplace. This all seemed logical, since Authors.me was solving a problem for both sides of this market, but there were some issues. Setting aside the challenge of finding aspiring writers, the authors who were approached often didn't have a lot of extra money for a listing on Authors.me, much less to pay for additional data. And since Authors.me didn't have a brand name yet or a track record of breaking new writers, it was hard to get writers to shell out money and take the leap of faith. On the other side, most publishers didn't believe technology could predict something better than an editor or were worried that the service could put editors out of work. And while many publishers would say they'd try Authors.me, very few actually were becoming customers.

Still, Monica knew the market well and knew there was a need and that there would be an eventual shift to more data-driven decision processes. At this point, Monica and I were working together at Techstars and started to question the initial theory of who she thought her customers would be. She felt that she was getting enough interest from publishers about Authors.me's ability to predict outcomes, and she started testing the idea that a marketplace wasn't the product, but instead a data platform for publishers was the product.

She started having some very promising conversations with all the top publishers and for a couple of months it looked as though they were moving in the right direction. Publishers seemed to be interested in a platform that would help them better predict what books should be published and how those books should be edited to better suit the target audience. But closed deals weren't moving as fast as Monica hoped. To accelerate sales into the publishing market, Monica closed a major partnership with a leading book printing company who from then on would be the primary sales channel for the company, albeit at a slow pace, given that they are still selling to publishers.

However, at this point, Monica paused and decided to see if she could disprove her current theory that publishers were her target customer. Rather than look at all the reasons why they should be, she asked herself why they might not be. She questioned whether the publishers could move fast enough in their decision making. She questioned the volume of published materials relative to the revenue they would produce, and she looked at the total universe of potential customers. And while it did look like there was a business here, her confidence in building it in a time frame that would allow her to build a profitable business looked challenging.

It was at this point that Monica questioned her who again and wondered who else might benefit from this product. She had thought about TV and film studios in the past, but dismissed them based on a couple of assumptions. First, she assumed they would be harder to meet than publishers. She was also concerned that the market of big studios wasn't big enough in terms of total customer potential, and, finally, she wasn't sure if finding top writers was a challenge in TV and film, as it was in the publishing world, which she knew well. She decided to test this and (by leveraging the TechStars Network) landed a few initial meetings with some studios. She very quickly learned that not only did studios have the same issue, but mistakes were much more costly, and therefore solving the problem of identifying great content by crunching data was a high priority for most studios.

Monica also learned that there were many more studios and production houses than she had originally thought. And after a few conversations she realized that not only was there a big market here, but that this segment could move faster, had more money to spend, and had a higher velocity of content that they were trying to produce. After a little more validation, Monica shifted her who focus, changed the company name to Storyfit (a better name for her new customer type), and directed her efforts at this segment. Fast-forward 18 months, Storyfit is working with (or soon to be working with) several of the major studios and already delivering data that is driving the content that you are likely watching on TV and in theaters.

Lessons Monica Learned from Authors.me

As you can see from this story, Monica had strong convictions about who they originally believed their ICP was; however, she and her colleagues didn't take the time to prove it. They spent months and months selling to a customer set that was never going to be able to pay enough or provide enough repeat business to build a big business. And while this customer set did have a need for the product, it wasn't strong enough for Authors.me to build a big and sustainable business with this customer set.

Fortunately Monica figured it out before the business failed and started testing new potential segments by using the customer development process to test new theories of her ICP. How did she do it?

First she took a step back and opened up her mind to being wrong about her ICP. While this may sound simple in theory, in practice it's much harder. Think about it. You've spent months or maybe longer passionately focused on building a product for a specific customer type, and in your mind, you knew exactly who that customer was. The simple act of questioning your own resolve is challenging for anyone, but especially when you've already poured months or years of work into it and likely even put yourself out there in public with this resolve. It can be a big blow to anyone's ego. But that's exactly what you have to do, you have to be open to being wrong.

Second she went back to square one and did the work to define her who again. In this case we were fortunate to have some data about what wasn't working, and she took the information she had about the customer she was trying to sell to into account. The three things that stood out were (1) historically, publishing was a slower moving industry; (2) data wasn't as widely used yet, compared to other industries; and (3) budgets in publishing were smaller, when existent at all, for any outside resources. Publishers didn't want to pay and most writers didn't have the money or foresight to see how this product could help them create better work, faster.

Third, she came up with a new list of potential segments and prospects within those segments to test. This included screenwriting for TV and film studios, among others.

And finally, the really tedious work began—Monica had as many conversations with potential customers as possible. Unlike the first and second time around, this time she approached each conversation to learn something rather than to sell something. She took the time to learn about internal processes, who would be the users, and who would be the decision makers (and whether it was one person with both roles). She asked about the use of technology inside the creative process, as well as budgeting for this type of technology.

And the results were great. She learned that large studios saw the emergence of Netflix as a big challenge because of their ability to, quickly, produce high-quality content for specific viewer types, while the big studios did not have the resources or DNA to build internal teams to tackle the same task. While they are great at producing great content, their model of identifying and modifying potential movies and TV shows is based more on gut instincts than on data. She also learned that there was budget set aside in the development process for research and that the Storyfit product could fall into that line item. That not only meant that there was money for the Storyfit product, but that there was money each time a new project was being considered.

She discovered several wins in these conversations. Not only would StoryFit have a head start on the technology, thanks to their work in publishing, but the book knowledge brought with it a level of trust and respect in Hollywood. Some of the most important movie franchises come from books. This deep understanding of stories across multiple media gave StoryFit a strong differentiator from other analytics companies. (And that's when the technology found its new name, from Authors.me to StoryFit.)

And with that, Storyfit had identified their who and was one step closer to identifying product market fit (we discuss this further on in the “Product–Market Direction and the Quest for Product–Market Fit” section).

The Methodology for Finding Your ICP

So what's the work you have to do to identify your ICP? Well, as discussed in Chapter 1, it starts with doing the who work. Once you have your who theory articulated, you are ready to start having conversations around trying to prove it right or wrong. As you recall, you've taken the time to describe who you think your customer will be, and you've taken the time to write down who you believe your top prospective customers will be. This is where you take that work and test it. Leverage your network and find out how you can get warm introductions to people who work with your target customers and start collecting data.

I have a very specific style and methodology here that I will describe, with the caveat that you will need to figure out what works bests for you and the industry you are focused on. There is much that you can pull from my methods; however, you will ultimately need to make the process your own.

Step 1

I use LinkedIn and the Techstars network to see where I can get warm introductions to either (a) the target job title at the company I'm trying to talk to or (b) someone senior (ideally C-level) who can point me in the right direction and even make a subsequent introduction.

Step 2

I ask for a 15-minute meeting. I make it clear that the purpose of this meeting is to share with them what I'm working on and to see if a longer meeting would be appropriate, where the longer meeting would be focused on digging in on the product idea in order to lean on their expertise in designing our product.

- Note here that while I'm using the product concept as the entry point for the conversation, inherently I'm testing the customer appetite for the concept. If they are not open to the conversation, I very politely ask, why under the pretense that it will help me figure out if I should spend any additional time working on this problem.

- Also note that when warm introductions are made, most people will give you that 15-minute meeting as it is respectful of their time and unobtrusive.

- Final note: when you are onto something, those 15 minutes consistently extend to 30 minutes or more.

Step 3

This is the data collection meeting. Sometimes this happens in that first 15-minute meeting, sometimes it's in a follow-up meeting with that person (or the person they've directed you to), and sometimes it happens over the course of a few meetings with a few different people. There isn't a wrong answer here, as long as your goal stays the same, which is to collect as much data as possible on whether you are solving a real problem for this customer and if you have the right customer type.

Here are things you should be looking for in these meetings:

- Are the meeting attendees engaged or does it feel like they are burdened (record your gut response)?

- How do they rank the problem (and your solution) relative to their job and the things they are working on in the near term?

- Ask the same question, but for the company, not just their job.

- Can you get a sense for what you expect to charge relative to what they can afford?

- Are they pushing for time frames and follow-up (or are they even open to being an early customer)?

And here are some things to look out for in these meetings:

- Happy ears—this is you wanting so badly to be correct that you think this potential customer is excited to buy from you when in actuality they may just be nice or not know how to say no.

- A real problem may be mentioned, but given lower priority relative to other things they or their company needs to accomplish.

- A real problem that needs to be solved may be mentioned, but small or no budget is currently being allocated to solving the problem (relative to your expected cost).

- The right problem may be identified, but the wrong person in the company is present at the meeting. This is a really hard one to figure out without offending the person you are meeting with. My style is to simply be transparent from the beginning so it's possible to ask that question without it being awkward.

Now we have developed strong conviction around our who. We have a good idea of the problem we are solving and a good idea of who we are solving it for, and now it's time to use the customer development process to develop strong product–market direction on the quest for product–market fit.

Product–Market Direction and the Quest for Product–Market Fit

Our company, Chowbotics, had developed a product that could work for offices, hospitals, and restaurants as well as grocery stores. We were getting inbound interest from major brands in all these markets. Amos and Techstars advised us to identify just one beachhead market, focus on it, develop marketing and successful case studies for that beachhead market, scale sales there and later target other markets.

Our sales team initially got excited seeing all the inbound interest from several markets and didn't follow the “focus on one beachhead market” approach. After a few months of getting overwhelmed, and taking baby steps in multiple markets instead of getting solid traction in one market, we pivoted to the “beachhead market” approach and quickly saw results. We now have hundreds of deployments in offices across the United States and Europe.

—Deepak Sekar, founder and CEO of Chowbotics

At this point you are feeling pretty good about your who, which means that you also feel good that the problem you thought you were solving is actually a problem worth solving. This is a great step in the right direction but just because you know your who and have validated the problem doesn't mean you have product–market fit, it just means that you have a reasonably strong idea that a group of people have a problem worth solving.

Understanding Product–Market Fit

Chances are that if you've read any startup literature, pitched your business to investors, or even just talked to other startup people about your company that you are familiar with the concept of product–market fit. In the case that you are not, this is a really important concept to understand and internalize. Wikipedia's definition of product–market fit is the degree to which a product satisfies a strong market demand. To simplify it, I tell my portfolio companies that you know you have achieved product–market fit when some group of people can't (or don't want to) live without your product. Important to note here is that just because you have product–market fit doesn't mean you have the right product to build a big company. If that group of people is very small or not willing to pay what you need to charge, then your company can still fail; however, without product–market fit you will have zero chance of building a big company because it essentially means that no one needs your product (or at least for any sustained period of time).

It can take months or even years to fully achieve product–market fit. Once you've achieved it, it's likely that you've built or at least are on the way to building a really big business. Some great examples of companies who have achieved incredible product–market fit are Salesforce.com, Apple Computer Company, and Google. These companies all have customers who either need their products, or prefer their products compared to their competitor's products because it satisfies their unique needs. And while some of that can be attributed to brand loyalty now, that brand promise was built on the back of achieving product–market fit for their target customer set.

Knowing Your Product–Market Direction

Long before you achieve product–market fit, however, you need to get product–market direction. I've talked about this concept for several years. Upon the writing of this book, I did a lot of research to figure out where I originally heard the concept but couldn't locate anything. I don't believe I'm the first person to use this concept and for the sake of this book, if I'm not giving someone the proper attribution, please accept my apologies and thanks for the great concept.

Product–market direction is exactly that. It means you've identified who you are targeting for the problem you are attempting to solve and that you have directional indicators that the product you are building is heading in the right direction.

There is a very important attribute that we need to tease out here and a key differentiator between a salesperson and the person in your organization doing customer development. If you go back to the “Sales versus Customer Development” section, you'll recall that a salesperson needs a reasonably well-defined product to sell. And you'll also recall that until you have that well-defined product, you are in customer development mode. There is an aspect of this role that is a hybrid of a product person and a salesperson. It's the role of the person doing customer development to keep searching for those directional points, and it's a hard and important balance to strike.

Think of it like this, the person doing customer development needs to have enough of a product mindset to ask questions, listen really well, and direct both customers and your company's team to build the right product while also being able to identify when a product threshold has been met. That customer development person can actually turn an exploratory conversation into a sale and revenue for your company.

This rarely happens as one step and almost never happens with the first iteration of a product. Much more frequently, it is series of product iterations (sometimes dozens or more) over a longer period of time (months and years). Sometimes people refer to these iterations as pivots, which isn't necessarily wrong but the concept of pivot has adopted a pretty specific definition and negative connotation to “whatever you were doing was wrong, so you are going to do something completely different.”

I think about it more like sailing. When you sail, you know your starting point and you know your ending point. What the sailor doesn't always know is which way the wind is blowing and how it will shift while trying to get from point A to point B. Sometimes the wind is at your back, sometimes it's on one of your sides, and sometimes you are sailing straight into the wind. If you are out for a long enough trip it's likely the wind will change several times, meaning you'll need to change the direction and type of sail you will need. Your sailboat almost never goes directly straight and instead, in order to go from point A to point B, you and your crew will need to tack. This means the front of your boat is going left and right and left and right in order to “head straight” to your destination. Sometimes those tacks are very small and sometimes they are very large.

You can think about achieving product–market fit as a destination. And along the way you are tacking your business by looking for the product–market direction.

Every great company out there has gone through several iterations taking them from directional point to directional point. Yelp started as a social network asking friends for recommendations, Groupon was originally a platform for charitable causes, YouTube was originally a video dating service, and Slack was a feature of the video game Glitch (see https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/308975). In all four cases the CEOs of these companies recognized a couple of things. First was that their who was a group worth addressing, next that there was a problem that needed to be solved, and also that the product they originally brought to market had attractive attributes but was not exactly the right product to build a big company.

How Slack Tacked Its Way to Success

Let's talk about Slack because not only do I love this example but it is a great example of a company that continues to tack in order to maintain product–market fit (because, yes, it's something you can lose, too, if you don't continue to innovate). Originally, Slack was nothing more than a feature inside the video game Glitch. While the game was reasonably successful, the founders noticed something interesting, which was the way that their players socialized with one another in the game, which was to say, a lot and in depth.

The founders had the foresight to pull the feature out of the game and create Slack. That in and of itself is a big pivot, but that isn't what we are going to focus on here. What happened next is what I find truly remarkable and a great example of looking for product–market directional points as a way to continue to grow.

Today a large number of businesses use Slack as a communication tool within the company, in teams within the company, with their customers, and in many other ways. But in order to get there Slack had to listen to what their users were telling them (directly and indirectly) and continually evolve the product. They needed to add ways to keep communication separate and secure: they needed to have desktop and mobile experiences as well as experience options for non-Slack users so that their customers could leverage the Slack platform. And now, after dozens and dozens of product iterations, Slack is one of the most widely used business communications platforms around.

* * *

Identifying product–market direction is difficult and sometimes feels like one of the most tedious parts of building a company. You have a strong conviction of who your customer is and you know deep in your bones the problem you are solving. And on your quest to find product–market fit it's likely you will have many iterations of your product. Some will be awesome and others you will simply throw away. And while those times often feel like wasted time and work they are actually crucial for you to get from point A to point B and ultimately achieve product–market fit.

Now It's Your Turn to Start the Customer Development Process

We will break the customer development process into five steps:

- Create a list of initial targets—this should be a combination of warm introductions and people you do not know.

- Create a list of questions you need answered and data you need to collect to support your W3 theory.

- Schedule interview/meetings.

- Collect and analyze the data.

- Ask questions.

- Close beta customers.

- Ask more questions.

- Refine/repeat.