Chapter 28

Revenue: identify the contract and performance obligations

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- 2 IDENTIFY THE CONTRACT WITH THE CUSTOMER

- 2.1 Attributes of a contract

- 2.1.1 Application questions on attributes of a contract

- 2.1.2 Parties have approved the contract and are committed to perform their respective obligations

- 2.1.3 Each party’s rights regarding the goods or services to be transferred can be identified

- 2.1.4 Payment terms can be identified

- 2.1.5 Commercial substance

- 2.1.6 Collectability

- 2.2 Contract enforceability and termination clauses

- 2.2.1 Application questions on contract enforceability and termination clauses

- 2.2.1.A Evaluating termination clauses and termination payments in determining the contract duration

- 2.2.1.B Evaluating the contract term when only the customer has the right to cancel the contract without cause

- 2.2.1.C Evaluating the contract term when an entity has a past practice of not enforcing termination payments

- 2.2.1.D Accounting for a partial termination of a contract

- 2.2.1.E Accounting for consideration that was received from a customer, but not recognised as revenue, when the contract is cancelled

- 2.2.1.F Services provided during a period after contract expiration

- 2.2.1 Application questions on contract enforceability and termination clauses

- 2.3 Combining contracts

- 2.4 Contract modifications

- 2.4.1 Contract modification represents a separate contract

- 2.4.2 Contract modification is not a separate contract

- 2.4.3 Application questions on contract modifications

- 2.4.3.A When to evaluate the contract under the contract modification requirements

- 2.4.3.B Reassessing the contract criteria if a contract is modified

- 2.4.3.C Distinguishing between a contract modification and a change in the estimated transaction price due to variable consideration after contract inception

- 2.4.3.D Distinguishing between a contract modification and a marketing offer

- 2.4.3.E Contract modification that decreases the scope of the contract

- 2.4.3.F Accounting for a ‘blend-and-extend’ contract modification

- 2.5 Arrangements that do not meet the definition of a contract under the standard

- 2.1 Attributes of a contract

- 3 IDENTIFY THE PERFORMANCE OBLIGATIONS IN THE CONTRACT

- 3.1 Identifying the promised goods or services in the contract

- 3.1.1 Application questions on identifying promised goods or services

- 3.1.1.A Assessing whether pre-production activities are a promised good or service

- 3.1.1.B The nature of the promise in a typical stand-ready obligation

- 3.1.1.C Considering whether contracts with a stand-ready element include a single performance obligation that is satisfied over time

- 3.1.1.D Evaluating whether an exclusivity provision in a contract with customer represents a promised good or service

- 3.1.1 Application questions on identifying promised goods or services

- 3.2 Determining when promises are performance obligations

- 3.2.1 Determination of ‘distinct’

- 3.2.1.A Capable of being distinct

- 3.2.1.B Distinct within the context of the contract

- 3.2.1.C How should an entity determine whether ‘connected’ hardware sold with cloud services represent one or more performance obligations?

- 3.2.1.D How would entities determine whether implementation services are distinct?

- 3.2.2 Series of distinct goods or services that are substantially the same and have the same pattern of transfer

- 3.2.2.A The series requirement: Consecutive transfer of goods or services

- 3.2.2.B The series requirement versus treating the distinct goods or services as separate performance obligations

- 3.2.2.C Assessing whether a performance obligation consists of distinct goods or services that are ‘substantially the same’

- 3.2.2.D When to apply the series requirement

- 3.2.2.E Do all stand-ready obligations meet the criteria to be accounted for as a series?

- 3.2.3 Examples of identifying performance obligations

- 3.2.1 Determination of ‘distinct’

- 3.3 Promised goods or services that are not distinct

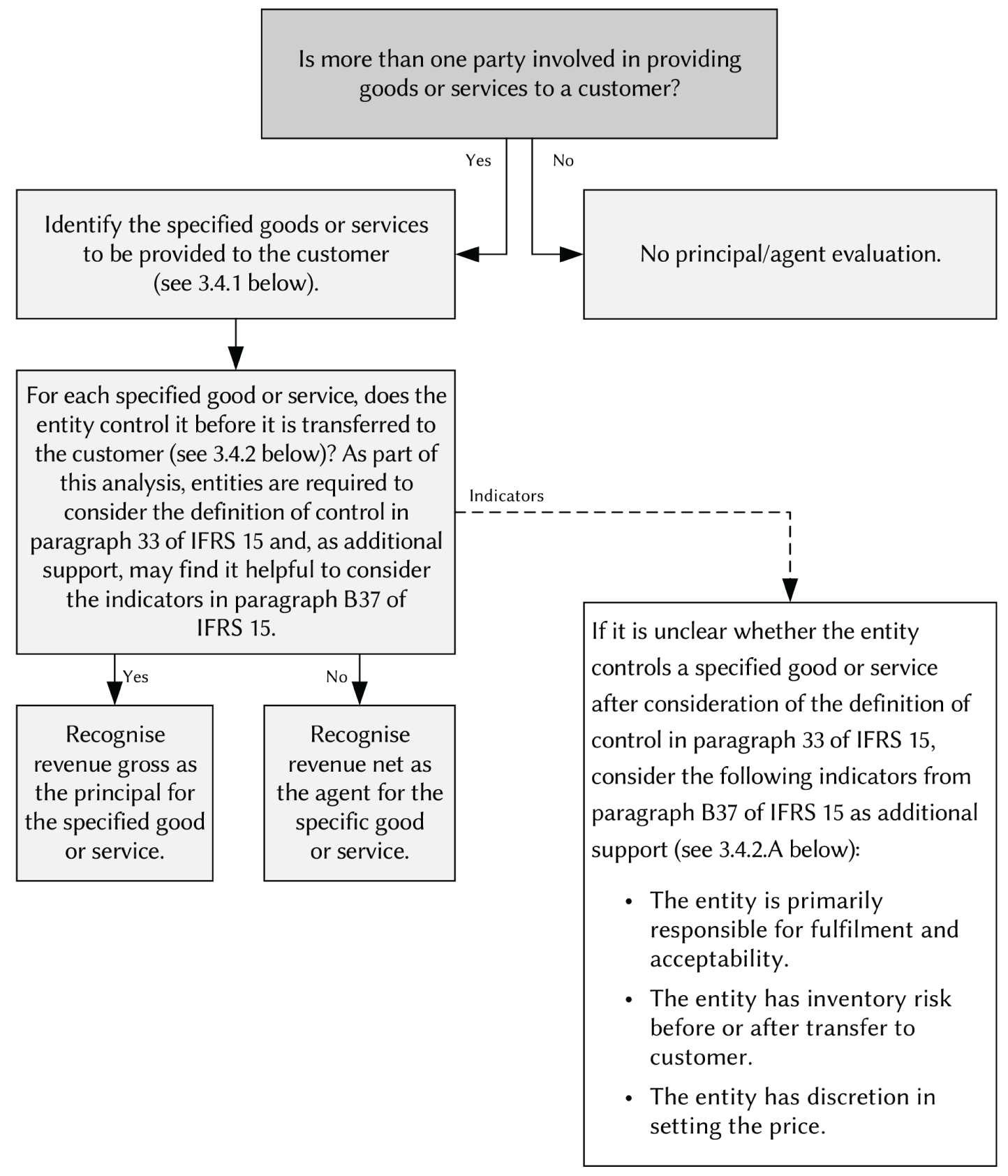

- 3.4 Principal versus agent considerations

- 3.5 Consignment arrangements

- 3.6 Customer options for additional goods or services

- 3.6.1 Application questions on customer options for additional goods or services

- 3.6.1.A Which transactions to consider when assessing customer options for additional goods or services

- 3.6.1.B Nature of evaluation of customer options: quantitative versus qualitative

- 3.6.1.C Distinguishing between a customer option and variable consideration

- 3.6.1.D When, if ever, to consider the goods or services underlying a customer option as a separate performance obligation when there are no contractual penalties

- 3.6.1.E Volume rebates and/or discounts on goods or services: customer options versus variable consideration

- 3.6.1.F Considering the class of customer when evaluating whether a customer option is a material right

- 3.6.1.G Considering whether prospective volume discounts determined to be customer options are material rights

- 3.6.1.H Considering whether a renewal option is a material right

- 3.6.1.I Considering whether a loyalty or reward programme is a material right

- 3.6.1.J Accounting for the exercise of a material right

- 3.6.1.K Customer options that provide a material right: Evaluating whether there is a significant financing component

- 3.6.1.L Customer options that provide a material right: recognising revenue when there is no expiration date

- 3.6.1 Application questions on customer options for additional goods or services

- 3.7 Sale of products with a right of return

- 3.1 Identifying the promised goods or services in the contract

List of examples

- Example 28.1: Oral contract

- Example 28.2: Collectability of the consideration

- Example 28.3: Assessing collectability for a portfolio of contracts

- Example 28.4: Duration of a contract with a termination penalty

- Example 28.5: Duration of a contract without a termination penalty

- Example 28.6: Partial termination of a contract

- Example 28.7: Services provided during a period after contract expiration

- Example 28.8: Unapproved change in scope and price

- Example 28.9: Determining whether the amount of consideration reflects the stand-alone selling price of additional goods or services

- Example 28.10: Modification of a contract for goods

- Example 28.11: Modification of a services contract

- Example 28.12: Modification of a contract for goods

- Example 28.13: Modification resulting in a cumulative catch-up adjustment to revenue

- Example 28.14: Contract modification that decreases the scope of the promised goods or services in a contract

- Example 28.15: Blend-and-extend contract modification

- Example 28.16: Explicit and implicit promises in a contract

- Example 28.17: Identification of promised good or service in a contract by a stock exchange that provides listing service to a customer

- Example 28.18: Determining the nature of the promise in a contract with a stand-ready element

- Example 28.19: Significant integration service

- Example 28.20: Significant customisation service

- Example 28.21: Highly interdependent and highly interrelated

- Example 28.22: Identification of performance obligations in a contract for the sale of a real estate unit that includes the transfer of land

- Example 28.23: Hardware sold with cloud services

- Example 28.24: Implementation services are distinct

- Example 28.25: Implementation services are not distinct

- Example 28.26: Allocation of variable consideration for a series versus a single performance obligation comprising non-distinct goods and/or services

- Example 28.27: A series in which the goods or services need not be consecutively transferred

- Example 28.28: A series for which the accounting result would be different if not treated as a series

- Example 28.29: IT outsourcing

- Example 28.30: Transaction processing

- Example 28.31: Hotel management

- Example 28.32: Determining whether promised goods and services represent a series

- Example 28.33: Goods and services are not distinct

- Example 28.34: Determining whether goods or services are distinct (Case A and Case B)

- Example 28.35: Determining whether goods or services are distinct (Case C – Case E)

- Example 28.36: Entity is both a principal and an agent

- Example 28.37: Entity is an agent

- Example 28.38: Entity is a principal

- Example 28.39: Promise to provide goods or services (entity is a principal) (office maintenance service)

- Example 28.40: Promise to provide goods or services (entity is a principal) (airline tickets)

- Example 28.41: Arranging for the provision of goods or services (entity is an agent)

- Example 28.42: Entity is a principal and an agent in the same contract

- Example 28.43: Option that provides the customer with a material right (discount voucher)

- Example 28.44: Evaluating a customer option when the stand-alone selling price is highly variable

- Example 28.45: Variable consideration (IT outsourcing arrangement)

- Example 28.46: Customer option that is not a material right

- Example 28.47: Customer option that is a material right

- Example 28.48: Customer option

- Example 28.49: Variable consideration (variable quantities of goods or services)

- Example 28.50: Customer option with no contractual penalties

- Example 28.51: Customer option with contractual penalties

- Example 28.52: Class of customer evaluation

- Example 28.53: Volume discounts

- Example 28.54: Evaluating a customer option with volume discounts

- Example 28.55: Option that provides the customer with a material right (renewal option)

- Example 28.56: Exercise of a material right under the requirements for changes in the transaction price

Chapter 28

Revenue: identify the contract and performance obligations

1 INTRODUCTION

Revenue is a broad concept that is dealt with in several standards. This chapter and Chapters primarily cover the requirements for revenue arising from contracts with customers that are within the scope of IFRS 15 – Revenue from Contracts with Customers. This chapter deals with identifying the contract and identifying performance obligations. Refer to the following chapters for other requirements of IFRS 15:

- Chapter – Core principle, definitions and scope.

- Chapter – Determining the transaction price and allocating the transaction price.

- Chapter – Recognising revenue.

- Chapter – Licences, warranties and contract costs.

- Chapter – Presentation and disclosure requirements.

Other revenue items that are not within the scope of IFRS 15, but arise in the course of the ordinary activities of an entity, as well as the disposal of non-financial assets that are not part of the ordinary activities of the entity, for which IFRS 15’s requirements are relevant, are addressed in Chapter 27.

In addition, this chapter:

- Highlights significant differences from the equivalent US GAAP standard, Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) 606 – Revenue from Contracts with Customers (together with IFRS 15, the standards) issued by the US Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) (together with the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), the Boards).

- Addresses topics on which the members of the Joint Transition Resource Group for Revenue Recognition (TRG) reached general agreement and our views on certain topics. TRG members’ views are non-authoritative, but entities should consider them as they apply the standards. Unless otherwise specified, these summaries represent the discussions of the joint TRG.

The views we express in this chapter may evolve as application issues are identified and discussed among stakeholders. The conclusions we describe in our illustrations are also subject to change as views evolve. Conclusions in seemingly similar situations may differ from those reached in the illustrations due to differences in the underlying facts and circumstances.

2 IDENTIFY THE CONTRACT WITH THE CUSTOMER

To apply the five-step model in IFRS 15, an entity must first identify the contract, or contracts, to provide goods or services to customers. A contract must create enforceable rights and obligations to fall within the scope of the model in the standard. Such contracts may be written, oral or implied by an entity’s customary business practices. For example, if an entity has an established practice of starting performance based on oral agreements with its customers, it may determine that such oral agreements meet the definition of a contract. [IFRS 15.10].

As a result, an entity may need to account for a contract as soon as performance begins, rather than delay revenue recognition until the arrangement is documented in a signed contract. Certain arrangements may require a written contract to comply with laws or regulations in a particular jurisdiction. These requirements must be considered when determining whether a contract exists.

In the Basis for Conclusions, the Board acknowledged that entities need to look at the relevant legal framework to determine whether the contract is enforceable because factors that determine enforceability may differ among jurisdictions. [IFRS 15.BC32]. The Board also clarified that, while the contract must be legally enforceable to be within the scope of the model in the standard, all of the promises do not have to be enforceable to be considered performance obligations (see 3.1 below). That is, a performance obligation can be based on the customer’s valid expectations (e.g. due to the entity’s business practice of providing an additional good or service that is not specified in the contract). In addition, the standard clarifies that some contracts may have no fixed duration and can be terminated or modified by either party at any time. Other contracts may automatically renew on a specified periodic basis. Entities are required to apply IFRS 15 to the contractual period in which the parties have present enforceable rights and obligations. [IFRS 15.11]. Contract enforceability and termination clauses are discussed at 2.2 below.

2.1 Attributes of a contract

To help entities determine whether (and when) their arrangements with customers are contracts within the scope of the model in the standard, the Board identified certain attributes that must be present. The Board noted in the Basis for Conclusions that the criteria are similar to those in previous revenue recognition requirements and in other existing standards and are important in an entity’s assessment of whether the arrangement contains enforceable rights and obligations. [IFRS 15.BC33].

IFRS 15 requires an entity to account for a contract with a customer that is within the scope of the model in the standard only when all of the following criteria are met: [IFRS 15.9]

- the parties to the contract have approved the contract (in writing, orally or in accordance with other customary business practices) and are committed to perform their respective obligations;

- the entity can identify each party’s rights regarding the goods or services to be transferred;

- the entity can identify the payment terms for the goods or services to be transferred;

- the contract has commercial substance (i.e. the risk, timing or amount of the entity’s future cash flows is expected to change as a result of the contract); and

- it is probable that the entity will collect the consideration to which it will be entitled in exchange for the goods or services that will be transferred to the customer. In evaluating whether collectability of an amount of consideration is probable, an entity shall consider only the customer’s ability and intention to pay that amount of consideration when it is due. The amount of consideration to which the entity will be entitled may be less than the price stated in the contract if the consideration is variable because the entity may offer the customer a price concession.

These criteria are assessed at the inception of the arrangement. If the criteria are met at that time, an entity does not reassess these criteria unless there is an indication of a significant change in facts and circumstances. [IFRS 15.13]. For example, as noted in paragraph 13 of IFRS 15, if the customer’s ability to pay significantly deteriorates, an entity would have to reassess whether it is probable that the entity will collect the consideration to which it is entitled in exchange for transferring the remaining goods or services under the contract. The updated assessment is prospective in nature and would not change the conclusions associated with goods or services already transferred. That is, an entity would not reverse any receivables, revenue or contract assets already recognised under the contract. [IFRS 15.BC34].

If the criteria are not met (and until the criteria are met), the arrangement is not considered a revenue contract under the standard and the requirements discussed at 2.5 below must be applied.

2.1.1 Application questions on attributes of a contract

2.1.1.A Master supply arrangements (MSA)

An entity may use an MSA to govern the overall terms and conditions of a business arrangement between itself and a customer (e.g. scope of services, pricing, payment terms, warranties and other rights and obligations). Typically, when an entity and a customer enter into an MSA, purchases are subsequently made by the customer by issuing a non-cancellable purchase order or an approved online authorisation that explicitly references the MSA and specifies the products, services and quantities to be delivered.

In such cases, the MSA is unlikely to create enforceable rights and obligations, which are needed to be considered a contract within the scope of the model in IFRS 15. This is because, while the MSA may specify the pricing or payment terms, it usually does not specify the specific goods or services, or quantities thereof, to be transferred. Therefore, each party’s rights and obligations regarding the goods or services to be transferred are not identifiable. It is likely that the MSA and the customer order, taken together, would constitute a contract under IFRS 15. As such, entities need to evaluate both the MSA and the subsequent customer order(s) together to determine whether and when the criteria in paragraph 9 of IFRS 15 are met. [IFRS 15.9].

If an MSA includes an enforceable clause requiring the customer to purchase a minimum quantity of goods or services, the MSA alone may constitute a contract under the standard because enforceable rights and obligations exist for this minimum amount of goods or services.

2.1.1.B Free trial period

Free trial periods are common in certain subscription arrangements (e.g. magazines, streaming services). A customer may receive a number of ‘free’ months of goods or services at the inception of an arrangement; before the paid subscription begins; or as a bonus period at the beginning or end of a paid subscription period.

Under IFRS 15, revenue is not recognised until an entity determines that a contract within the scope of the model exists. Once an entity determines that an IFRS 15 contract exists, it is required to identify the promises in the contract. Therefore, if the entity has transferred goods or services prior to the existence of an IFRS 15 contract, we believe that the free goods or services provided during the trial period would generally be accounted for as marketing incentives.

Consider an example in which an entity has a marketing programme to provide a three-month free trial period of its services to prospective customers. The entity’s customers are not required to pay for the services provided during the free trial period and the entity is under no obligation to provide the services under the marketing programme. If a customer enters into a contract with the entity at the end of the free trial period that obliges the entity to provide services in the future (e.g. signing up for a subsequent 12-month period) and obliges the customer to pay for the services, the services provided as part of the marketing programme may not be promises that are part of an enforceable contract with the customer.

However, if an entity, as part of a negotiation with a prospective customer, agrees to provide three free months of services if the customer agrees to pay for 12 months of services (effectively providing the customer a discount on 15 months), the entity would identify the free months as promises in the contract because the contract requires it to provide them.

The above interpretation applies if the customer is not required to pay any consideration for the additional goods or services during the trial period (i.e. they are free). If the customer is required to pay consideration in exchange for the goods or services received during the trial period (even if it is only a nominal amount), a different accounting conclusion could be reached. Entities need to apply judgement to evaluate whether a contract exists that falls within the scope of the standard.

2.1.1.C Consideration of side agreements

All terms and conditions that create or negate enforceable rights and obligations must be considered when determining whether a contract exists under the standard. Understanding the entire contract, including any side agreements or other amendments, is critical to this determination.

Side agreements are amendments to a contract that can be either undocumented or documented separately from the main contract. The potential for side agreements is greater for complex or material transactions or when complex arrangements or relationships exist between an entity and its customers. Side agreements may be communicated in many forms (e.g. oral agreements, email, letters or contract amendments) and may be entered into for a variety of reasons.

Side agreements may provide an incentive for a customer to enter into a contract near the end of a financial reporting period or to enter into a contract that it would not enter into in the normal course of business. Side agreements may entice a customer to accept delivery of goods or services earlier than required or may provide the customer with rights in excess of those customarily provided by the entity. For example, a side agreement may extend contractual payment terms; expand contractually stated rights; provide a right of return; or commit the entity to provide future products or functionality not contained in the contract or to assist resellers in selling a product. Therefore, if the provisions in a side agreement differ from those in the main contract, an entity should assess whether the side agreement creates new rights and obligations or changes existing rights and obligations. See 2.3 and 2.4 below, respectively, for further discussion of the standard’s requirements on combining contracts and contract modifications.

2.1.2 Parties have approved the contract and are committed to perform their respective obligations

Before applying the model in IFRS 15, the parties must have approved the contract. As indicated in the Basis for Conclusions, the Board included this criterion because a contract might not be legally enforceable without the approval of both parties. [IFRS 15.BC35]. Furthermore, the Board decided that the form of the contract (i.e. oral, written or implied) is not determinative, in assessing whether the parties have approved the contract. Instead, an entity must consider all relevant facts and circumstances when assessing whether the parties intend to be bound by the terms and conditions of the contract. In some cases, the parties to an oral or implied contract may have the intent to fulfil their respective obligations. However, in other cases, a written contract may be required before an entity can conclude that the parties have approved the arrangement. [IFRS 15.10].

In addition to approving the contract, the entity must be able to conclude that both parties are committed to perform their respective obligations. That is, the entity must be committed to providing the promised goods or services. In addition, the customer must be committed to purchasing those promised goods or services. In the Basis for Conclusions, the Board clarified that an entity and a customer do not always have to be committed to fulfilling all of their respective rights and obligations for a contract to meet this requirement. [IFRS 15.BC36]. The Board cited, as an example, a supply agreement between two parties that includes stated minimums. The customer does not always buy the required minimum quantity and the entity does not always enforce its right to require the customer to purchase the minimum quantity. In this situation, the Board stated that it may still be possible for the entity to determine that there is sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the parties are substantially committed to the contract. This criterion does not address a customer’s intent and ability to pay the consideration (i.e. collectability). Collectability is a separate criterion and is discussed at 2.1.6 below.

Termination clauses are also an important consideration when determining whether both parties are committed to perform under a contract and, consequently, whether a contract exists. See 2.2 below for further discussion of termination clauses and how they affect contract duration.

2.1.3 Each party’s rights regarding the goods or services to be transferred can be identified

This criterion is relatively straightforward. If the goods or services to be provided in the arrangement cannot be identified, it is not possible to conclude that an entity has a contract within the scope of the model in IFRS 15. The Board indicated that if the promised goods or services cannot be identified, the entity cannot assess whether those goods or services have been transferred because the entity would be unable to assess each party’s rights with respect to those goods or services. [IFRS 15.BC37].

2.1.4 Payment terms can be identified

Identifying the payment terms does not require that the transaction price be fixed or stated in the contract with the customer. As long as there is an enforceable right to payment (i.e. enforceability as a matter of law) and the contract contains sufficient information to enable the entity to estimate the transaction price (see further discussion in Chapter 29 at 2), the contract would qualify for accounting under the standard (assuming the remaining criteria set out in paragraph 9 of IFRS 15 have been met – see 2.1 above).

2.1.5 Commercial substance

The Board included a criterion that requires arrangements to have commercial substance (i.e. the risk, timing or amount of the entity’s future cash flows is expected to change as a result of the contract) to prevent entities from artificially inflating revenue. [IFRS 15.BC40]. The model in IFRS 15 does not apply if an arrangement does not have commercial substance. Historically, some entities in high-growth industries allegedly engaged in transactions in which goods or services were transferred back and forth between the same entities in an attempt to show higher transaction volume and gross revenue (sometimes known as ‘round-tripping’). This is also a risk in arrangements that involve non-cash consideration.

Determining whether a contract has commercial substance for the purposes of IFRS 15 may require significant judgement. In all situations, the entity must be able to demonstrate a substantive business purpose exists, considering the nature and structure of its transactions.

IFRS 15 does not contain requirements specific to advertising barter transactions. Entities need to carefully consider the commercial substance criterion when evaluating these types of transactions (see Chapter 29 at 2.6.2 for further discussion on barter transactions).

2.1.6 Collectability

Under IFRS 15, collectability refers to the customer’s ability and intent to pay the amount of consideration to which the entity will be entitled in exchange for the goods or services that will be transferred to the customer. An entity needs to assess a customer’s ability to pay based on the customer’s financial capacity and its intention to pay considering all relevant facts and circumstances, including past experiences with that customer or customer class. [IFRS 15.BC45].

In the Basis for Conclusions, the Board noted that the purpose of the criteria in paragraph 9 of IFRS 15 is to require an entity to assess whether a contract is valid and represents a genuine transaction. The collectability criterion (i.e. determining whether the customer has the ability and the intention to pay the promised consideration) is a key part of that assessment. In addition, the Board noted that, in general, entities only enter into contracts in which it is probable that the entity will collect the amount to which it will be entitled. [IFRS 15.BC43]. That is, in most instances, an entity would not enter into a contract with a customer if there was significant credit risk associated with that customer without also having adequate economic protection to ensure that it would collect the consideration. The IASB expects that only a small number of arrangements may fail to meet the collectability criterion. [IFRS 15.BC46E].

Paragraph 9(e) of IFRS 15 requires an entity to evaluate at contract inception whether it is probable that it will collect the consideration to which it will be entitled in exchange for the goods or services that will be transferred to a customer. An entity is also required to reassess collectability after contract inception, when significant facts and circumstances change (see 2.1.6.A below for further discussion). We discuss each of the italicised concepts below.

Probable – For purposes of this analysis, the meaning of the term ‘probable’ is consistent with the existing definition in IFRS, i.e. ‘more likely than not’. [IFRS 15 Appendix A]. If it is not probable that the entity will collect amounts to which it is entitled, the model in IFRS 15 is not applied to the contract until the concerns about collectability have been resolved. However, other requirements in IFRS 15 apply to such arrangements (see 2.5 below for further discussion). ASC 606 also uses the term ‘probable’ for the collectability assessment. However, ‘probable’ under US GAAP is a higher threshold than under IFRS.1

Consideration to which it will be entitled in exchange for the goods or services that will be transferred to a customer – The amount of consideration that is assessed for collectability is the amount to which the entity will be entitled for the goods or services that will be transferred to the customer. That is, the amount of consideration assessed for collectability is often the transaction price, but it may be a lesser amount in certain circumstances, as discussed further below.

It is important to note that the transaction price might be less than the stated contract price for the goods or services in the contract. Entities need to determine the transaction price in Step 3 of the model (as discussed in Chapter 29 at 2) before assessing the collectability of that amount. The contract price and transaction price most often will differ because of variable consideration (e.g. rebates, discounts or explicit or implicit price concessions) that reduces the amount of consideration stated in the contract. For example, the transaction price for the items expected to be transferred may be less than the stated contract price for those items if an entity concludes that it has offered, or is willing to accept, a price concession on products sold to a customer. See Chapter 29 at 2.2.1.A for further discussion on price concessions.

An entity deducts from the contract price any variable consideration that would reduce the amount of consideration to which it expects to be entitled (e.g. an estimated price concession) at contract inception in order to derive the transaction price for those items. The collectability assessment is then performed on the determined transaction price.

Paragraph 9(e) of IFRS 15 specifies that an entity should assess only the consideration to which it will be entitled in exchange for the goods or services that will be transferred to the customer (rather than the total amount promised for all goods or services in the contract). [IFRS 15.9(e)]. In the Basis for Conclusions, the Board noted that, if the customer were to fail to perform as promised and the entity were able to stop transferring additional goods or services to the customer in response, the entity would not consider the likelihood of payment for those goods or services that would not be transferred in its assessment of collectability. [IFRS 15.BC46].

In the Basis for Conclusions, the Board also noted that the assessment of collectability criteria requires an entity to consider how the entity’s contractual rights to the consideration relate to its performance obligations. That assessment considers the business practices available to the entity to manage its exposure to credit risk throughout the contract (e.g. through advance payments or the right to stop transferring additional goods or services). [IFRS 15.BC46C]. The FASB’s standard includes additional guidance to clarify the intention of the collectability assessment. However, the IASB stated in the Basis for Conclusions on IFRS 15 that it does not expect differences in outcomes under IFRS and US GAAP in relation to the evaluation of the collectability criterion. [IFRS 15.BC46E].

In addition to the IFRS 15 collectability assessment, an entity has to assess any contract assets or trade receivables arising from an IFRS 15 contract under the expected credit loss model in IFRS 9 – Financial Instruments (for further discussion see Chapter 32 at 2.1.3 and Chapter 51).

At contract inception, significant judgement is required to determine when an expected partial payment indicates that: (1) there is an implied price concession in the contract that affects the determination of the transaction price and the amount assessed for collectability under IFRS 15; (2) there is an expected credit loss (accounted for as an impairment loss under IFRS 9); or (3) the arrangement lacks sufficient substance to be considered a contract under the standard. See Chapter 29 at 2.2.1.A for further discussion on implicit price concessions.

(i) Variable consideration versus credit risk

In the Basis for Conclusions on IFRS 15, the IASB acknowledged that in some cases, it may be difficult to determine whether the entity has implicitly offered a price concession (i.e. variable consideration) or whether the entity has chosen to accept the risk of default by the customer of the contractually agreed-upon consideration (i.e. impairment losses under IFRS 9, see Chapter 51). [IFRS 15.BC194]. The Board did not develop detailed guidance for distinguishing between price concessions (recognised as variable consideration through revenue) and an expected credit loss to be accounted for as an impairment loss under IFRS 9 (i.e. outside of revenue). Therefore, entities need to consider all relevant facts and circumstances when analysing situations in which, at contract inception, an entity is willing to accept a lower price than the amount stated in the contract. In Chapter 29 at 2.2.1.A, we discuss certain factors that may suggest the entity has implicitly offered a price concession to the customer.

After the entity has determined the amount to assess for collectability under paragraph 9(e) of IFRS 15, it also has to apply the requirements in IFRS 9 to account for any expected credit loss for the receivable (or contract asset) that is recorded (i.e. after consideration of any variable consideration, such as an implicit price concession). Also, it should present any resulting impairment loss as an expense under IFRS 9 (i.e. not as a reduction of the transaction price).

Examples 2 (included as Example 29.2 in Chapter 29 at 2.2.1.A), 3 and 23 (included as Example 29.7 in Chapter 29 at 2.2.3) from the standard illustrate situations where the transaction price that is evaluated for collectability is not the amount stated in the contract. In contrast, the TRG discussed an example (included at 2.1.6.A below) in which an entity, at contract inception, believes it is probable that its customers will pay amounts owed and the transaction price (i.e. revenue recorded) equals the contract price, even though, on a portfolio basis, 2% is not expected to be collected.

(ii) Example of assessing the collectability criterion

The standard provides the following example of how an entity would assess the collectability criterion. [IFRS 15.IE3-IE6].

2.1.6.A Assessing collectability for a portfolio of contracts

At the January 2015 TRG meeting, the TRG members considered how an entity would assess collectability if it has a portfolio of contracts. The TRG members generally agreed that if an entity has determined it is probable that a customer will pay amounts owed under a contract, but the entity has historical experience that it will not collect consideration from some of the customers within a portfolio of contracts (see 2.3.1 below), it would be appropriate for the entity to record revenue for the contract in full and separately evaluate the corresponding contract asset or receivable for impairment.2 That is, the entity would not conclude the arrangement contains an implicit price concession and would not reduce revenue for the uncollectable amounts. See Chapter 29 at 2.2.1.A for a discussion of evaluating whether an entity has offered an implicit price concession.

Consider the following example included in the TRG agenda paper:

Some TRG members cautioned that the analysis to determine whether to recognise an impairment loss for a contract in the same period in which revenue is recognised (instead of reducing revenue for an anticipated price concession) will require judgement.

2.1.6.B Determining when to reassess collectability

As discussed at 2.1 above, paragraph 13 of IFRS 15 requires an entity to reassess whether it is probable that it will collect the consideration to which it will be entitled when significant facts and circumstances change. Example 4 in IFRS 15 illustrates a situation in which a customer’s financial condition declines and its current access to credit and available cash on hand is limited. In this case, the entity does not reassess the collectability criterion. However, in a subsequent year, the customer’s financial condition further declines after losing access to credit and its major customers. Example 4 in IFRS 15 illustrates that this subsequent change in the customer’s financial condition is so significant that a reassessment of the criteria for identifying a contract is required, resulting in the collectability criterion not being met. [IFRS 15.IE14-IE17]. As noted in the TRG agenda paper, this example illustrates that it was not the Board’s intent to require an entity to reassess collectability when changes occur that are relatively minor in nature (i.e. those that do not call into question the validity of the contract). The TRG members generally agreed that entities need to exercise judgement to determine whether changes in the facts and circumstances are significant enough to indicate that a contract no longer exists under the standard.4

Example 4 in the standard also notes that the entity accounts for any impairment of the existing receivable in accordance with IFRS 9 (see Chapter 51). [IFRS 15.IE17].

2.2 Contract enforceability and termination clauses

An entity has to determine the duration of the contract (i.e. the stated contractual term or a shorter period) before applying certain aspects of the revenue model (e.g. identifying performance obligations, determining the transaction price). The contract duration under IFRS 15 is the period in which parties to the contract have present enforceable rights and obligations. An entity cannot assume that there are present enforceable rights and obligations for the entire term stated in the contract and it is likely that an entity will have to consider enforceable rights and obligations in individual contracts, as described in the standard.

The standard states that entities are required to apply IFRS 15 to the contractual period in which the parties have present enforceable rights and obligations. [IFRS 15.11]. For the purpose of applying IFRS 15, a contract does not exist if each party has the unilateral enforceable right to terminate a wholly unperformed contract without compensating each other or other parties. The standard defines a wholly unperformed contract as one for which ‘both of the following criteria are met: (a) the entity has not yet transferred any promised goods or services to the customer; and (b) the entity has not yet received, and is not yet entitled to receive, any consideration in exchange for promised goods or services.’ [IFRS 15.12].

The period in which enforceable rights and obligations exist may be affected by termination provisions in the contract. Significant judgement is required to determine the effect of termination provisions on the contract duration. Entities need to review the overall contractual arrangements, including any master service arrangements, wind-down provisions and business practices to identify terms or conditions that might affect the enforceable rights and obligations in their contracts.

Under the standard, this determination is critical because the contract duration to which the standard is applied may affect the number of performance obligations identified and the determination of the transaction price. It may also affect the amounts disclosed in some of the required disclosures. See 2.2.1.A below for further discussion on how termination provisions may affect the contract duration.

If each party has the unilateral right to terminate a ‘wholly unperformed’ contract (as defined in paragraph 12 of IFRS 15) without compensating the counterparty, IFRS 15 states that, for purposes of the standard, a contract does not exist and its accounting and disclosure requirements would not apply. This is because the contracts would not affect an entity’s financial position or performance until either party performs. Any arrangement in which the entity has not provided any of the contracted goods or services and has not received or is not entitled to receive any of the contracted consideration is considered to be a ‘wholly unperformed’ contract.

The requirements for ‘wholly unperformed’ contracts do not apply if the parties to the contract have to compensate the other party if they exercise their right to terminate the contract and that termination payment is considered substantive.

Under IFRS 15, entities are required to account for contracts with longer stated terms as month-to-month (or possibly a shorter duration) contracts if the parties can terminate the contract without penalty.

Entities need to consider all facts and circumstances to determine the contract duration. For example, entities may need to use significant judgement to determine whether a termination payment is substantive and the effect of a termination provision on contract duration.

2.2.1 Application questions on contract enforceability and termination clauses

2.2.1.A Evaluating termination clauses and termination payments in determining the contract duration

Entities need to carefully evaluate termination clauses and any related termination payments to determine how they affect contract duration (i.e. the period in which there are enforceable rights and obligations). TRG members generally agreed that enforceable rights and obligations exist throughout the term in which each party has the unilateral enforceable right to terminate the contract by compensating the other party. For example, if a contract includes a substantive termination payment, the duration of the contract would equal the period through which a termination penalty would be due. This could be the stated contractual term or a shorter duration if the termination penalty does not extend to the end of the contract. However, the TRG members observed that the determination of whether a termination penalty is substantive, and what constitutes enforceable rights and obligations under a contract, requires judgement and consideration of the facts and circumstances. The TRG agenda paper also noted that, if an entity concludes that the duration of the contract is less than the stated term because of a termination clause, any termination penalty needs to be included in the transaction price. If the termination penalty is variable, the requirements for variable consideration, including the constraint (see Chapter 29 at 2.2.3), apply.

The TRG members also agreed that if a contract with a stated contractual term can be terminated by either party at any time for no consideration, the contract duration ends when control of the goods or services that have already been provided transfers to the customer (e.g. a month-to-month service contract), regardless of the contract’s stated contractual term. In this case, entities also need to consider whether a contract includes a notification or cancellation period (e.g. the contract can be terminated with 90 days’ notice) that would cause the contract duration to extend beyond the date when control of the goods or services that have already been provided were transferred to the customer. If such a period exists, the contract duration would be shorter than the stated contractual term, but would extend beyond the date when control of the goods or services that have already been provided were transferred to the customer.5 Consider the following examples that illustrate how termination provisions affect the duration of a contract.

2.2.1.B Evaluating the contract term when only the customer has the right to cancel the contract without cause

Enforceable rights and obligations exist throughout the term in which each party has the unilateral enforceable right to terminate the contract by compensating the other party. The TRG members did not view a customer-only right to terminate sufficient to warrant a different conclusion than one in which both parties have the right to terminate, as discussed in 2.2.1.A above.

The TRG members generally agreed that a substantive termination penalty payable by a customer to the entity is evidence of enforceable rights and obligations of both parties throughout the period covered by the termination penalty. For example, consider a four-year service contract in which the customer has the right to cancel without cause at the end of each year, but for which the customer would incur a termination penalty that decreases each year and is determined to be substantive. The TRG members generally agreed that the arrangement would be treated as a four-year contract (see Example 28.4, Scenario B at 2.2.1.A above).

The TRG members also discussed situations in which a contractual penalty would result in including optional goods or services in the accounting for the original contract (see 3.6.1.D below).

The TRG members observed that the determination of whether a termination penalty is substantive, and what constitutes enforceable rights and obligations under a contract, requires judgement and consideration of the facts and circumstances. In addition, it is possible that payments that effectively act as a termination penalty and create or negate enforceable rights and obligations may not be labelled as such in a contract. The TRG agenda paper included an illustration in which an entity sells equipment and consumables. The equipment is sold at a discount, but the customer is required to repay some or all of the discount if it does not purchase a minimum number of consumables. The TRG paper concludes that the penalty (i.e. forfeiting the upfront discount) is substantive and is evidence of enforceable rights and obligations up to the minimum quantity. This example is discussed further at 3.6.1.D below. See 2.2.1.D below for another example.

If enforceable rights and obligations do not exist throughout the entire term stated in the contract the TRG members generally agreed that customer cancellation rights would be treated as customer options. Examples include, when there are no (or non-substantive) contractual penalties that compensate the entity upon cancellation and when the customer has the unilateral right to terminate the contract for reasons other than cause or contingent events outside the customer’s control. In the Basis for Conclusions, the Board noted that a cancellation option or termination right can be similar to a renewal option. [IFRS 15.BC391]. An entity would need to determine whether a cancellation option indicates that the customer has a material right that would need to be accounted for as a performance obligation (e.g. there is a discount for goods or services provided during the cancellable period that provides the customer with a material right) (see 3.6 below).6

2.2.1.C Evaluating the contract term when an entity has a past practice of not enforcing termination payments

A TRG agenda paper for the October 2014 TRG meeting noted that the evaluation of the termination payment in determining the duration of a contract depends on whether the law (which may vary by jurisdiction) considers past practice as limiting the parties’ enforceable rights and obligations. An entity’s past practice of allowing customers to terminate the contract early without enforcing collection of the termination payment only affects the contract duration in cases in which the parties’ legally enforceable rights and obligations are limited because of the lack of enforcement by the entity. If that past practice does not change the parties’ legally enforceable rights and obligations, the contract duration equals the period throughout which a substantive termination penalty would be due (which could be the stated contractual term or a shorter duration if the termination penalty did not extend to the end of the contract).7

2.2.1.D Accounting for a partial termination of a contract

We believe an entity should account for the partial termination of a contract (e.g. a change in the contract term from three years to two years prior to the beginning of year two) as a contract modification (see 2.4 below) because it results in a change in the scope of the contract. IFRS 15 states that ‘a contract modification exists when the parties to a contract approve a modification that either creates new or changes existing enforceable rights and obligations of the parties to the contract’. [IFRS 15.18]. A partial termination of a contract results in a change to the enforceable rights and obligations in the existing contract (see also further below 2.4.3.E for a contract modification that decreases the scope of a contract). This conclusion is consistent with TRG agenda paper no. 48, which states, ‘a substantive termination penalty is evidence of enforceable rights and obligations throughout the contract term. The termination penalty is ignored until the contract is terminated at which point it is accounted for as a modification’.8

Consider the following example:

2.2.1.E Accounting for consideration that was received from a customer, but not recognised as revenue, when the contract is cancelled

When a contract is cancelled (by either the customer or the entity) it is a contract modification that reduces the scope of the contract. As discussed at 2.2.1.D above and 2.4.3.E below such a modification would not be accounted for as a separate contract because it does not result in the addition of distinct goods or services. Rather, the accounting will depend on whether there are any remaining goods and services to be provided after the cancellation and, if so, whether they are distinct from the goods and services already provided.

If there are no remaining goods and services to be provided after the cancellation, the accounting depends on whether the consideration is refundable or non-refundable. To determine whether consideration is refundable or non-refundable, entities may need to consider termination penalties, legal requirements for refund, customary business practices of providing refunds or statements made to customers that create a constructive or legal obligation to provide a refund.

If the consideration received from the customer is refundable and there are no remaining goods and services to be provided after the cancellation, the entity has a refund liability. This might require the entity to reclassify any existing contract liability to refund liability. In some cases, the entity might ask the customer to waive their right to a refund of the consideration in exchange for vouchers, for example, and/or discounts on future goods or services. The accounting for such offers (including the accounting for the liability) depends on the specific facts and circumstances and may require judgement.

If the consideration received from the customer is non-refundable and there are no remaining goods and services to be provided after the cancellation, we believe that the entity can recognise revenue for the consideration received when the contract is cancelled, and the related contract liability would also be derecognised. This accounting treatment is similar to the application guidance for breakage (e.g. for gift cards, see Chapter 30 at 11 and the recognition of revenue for arrangements that fail the IFRS 15 contract criteria in accordance with paragraph 15 of IFRS 15 (see 2.5 below). In both of those situations, IFRS 15 provides guidance that permits an entity to derecognise a liability and recognise revenue, provided the relevant criteria are met, when: the entity expects the customer will not exercise its contractual rights (for breakage); [IFRS 15.B46] or the contract is effectively completed or cancelled (for contracts that do not meet the contract criteria in paragraph 9 of IFRS 15). [IFRS 15.15, BC48].

In some cases, an entity may be entitled to termination fees in the event of cancellation. The accounting for termination fees is discussed at 2.2.1.D above.

2.2.1.F Services provided during a period after contract expiration

If an entity continues to provide services to a customer during a period when a contract does not exist because a previous contract has expired and the contract has not yet been renewed, we believe that the entity would need to recognise revenue for providing those services on a cumulative catch-up basis at the time the contract is renewed (i.e. when enforceable rights and obligations exist between the entity and its customer). As discussed at 2 above, determining whether an enforceable contract exists under the model may require judgement and an evaluation of the relevant legal framework.

This approach to record revenue on a cumulative catch-up basis reflects the performance obligations that are partially satisfied at the time enforceable rights and obligations exist and is consistent with the overall principle of the standard that requires revenue to be recognised when (or as) an entity transfers control of goods or services to a customer under an enforceable contract. This conclusion is also consistent with the discussion in Chapter 30 at 3.4.6 on the accounting for goods or services provided to a customer before the contract establishment date.

Consider the following example:

An entity might receive consideration from the customer for the goods or services transferred before the existence of an enforceable contract. If so, the entity would need to follow the requirements in paragraphs 14-16 of IFRS 15 (discussed further at 2.5 below). This requires that when an arrangement does not meet the criteria to be a contract under the standard, an entity would recognise the non-refundable consideration received as revenue only if one of the two events has occurred (e.g. the entity has no remaining obligations to transfer goods or services to the customer and all, or substantially all, of the consideration promised by the customer has been received by the entity and is non-refundable).

2.3 Combining contracts

In most cases, entities apply the model to individual contracts with a customer. However, the standard requires entities to combine contracts entered into at, or near, the same time with the same customer (or related parties of the customer as defined in IAS 24 – Related Party Disclosures) if they meet one or more of the following criteria: [IFRS 15.BC74]

- the contracts are negotiated as a package with a single commercial objective;

- the amount of consideration to be paid in one contract depends on the price or performance of the other contract; or

- the goods or services promised in the contracts (or some goods or services promised in each of the contracts) are a single performance obligation.

In the Basis for Conclusions, the Board explained that it included the requirements on combining contracts in the standard because, in some cases, the amount and timing of revenue may differ depending on whether an entity accounts for contracts as a single contract or separately. [IFRS 15.BC71].

Entities need to apply judgement to determine whether contracts are entered into at or near the same time because the standard does not provide a bright line for making this assessment. In the Basis for Conclusions, the Board noted that the longer the period between entering into different contracts, the more likely it is that the economic circumstances affecting the negotiations of those contracts will have changed. [IFRS 15.BC75].

Negotiating multiple contracts at the same time is not sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the contracts represent a single arrangement for accounting purposes. In the Basis for Conclusions, the Board noted that there are pricing interdependencies between two or more contracts when either of the first two criteria (i.e. the contracts are negotiated with a single commercial objective or the price in one contract depends on the price or performance of the other contract) are met, so the amount of consideration allocated to the performance obligations in each contract may not faithfully depict the value of the goods or services transferred to the customer if those contracts were not combined.

The Board also explained that it decided to include the third criterion (i.e. the goods or services in the contracts are a single performance obligation) to avoid any structuring opportunities that would effectively allow entities to bypass the requirements for identifying performance obligations. [IFRS 15.BC73]. That is, an entity cannot avoid determining whether multiple promises made to a customer at, or near, the same time need to be bundled into one or more performance obligations in accordance with Step 2 of the model (see 3 below) solely by including the promises in separate contracts.

2.3.1 Portfolio approach practical expedient

Under the standard, the five-step model is applied to individual contracts with customers, unless the contract combination requirements discussed in 2.3 above are met. However, the IASB recognised that there may be situations in which it may be more practical for an entity to group contracts for revenue recognition purposes, rather than attempt to account for each contract separately. Specifically, the standard includes a practical expedient that allows an entity to apply IFRS 15 to a portfolio of contracts (or performance obligations) with similar characteristics if the entity reasonably expects that application of this practical expedient will not differ materially from applying IFRS 15 to the individual contracts (or performance obligations) within the portfolio. Furthermore, an entity is required to use estimates and assumptions that reflect the size and composition of the portfolio. [IFRS 15.4].

As noted above, in order to use the portfolio approach, an entity must reasonably expect that the accounting result will not be materially different from the result of applying the standard to the individual contracts. However, in the Basis for Conclusions, the Board noted that it does not intend for an entity to quantitatively evaluate every possible outcome when concluding that the portfolio approach is not materially different. Instead, they indicated that an entity should be able to take a reasonable approach to determine portfolios that are representative of its types of customers and that an entity should use judgement in selecting the size and composition of those portfolios. [IFRS 15.BC69].

Application of the portfolio approach will likely vary based on the facts and circumstances of each entity. An entity may choose to apply the portfolio approach to only certain aspects of the model (e.g. determining the transaction price in Step 3).

See 2.1.6.A above for a discussion on how an entity would assess collectability for a portfolio of contracts.

2.4 Contract modifications

Parties to an arrangement frequently agree to modify the scope or price (or both) of their contract. If that happens, an entity must determine whether the modification is accounted for as a new contract or as part of the existing contract. Generally, it is clear when a contract modification has taken place, but in some circumstances that determination is more difficult. To assist entities when making this determination, the standard states ‘a contract modification is a change in the scope or price (or both) of a contract that is approved by the parties to the contract. In some industries and jurisdictions, a contract modification may be described as a change order, a variation or an amendment. A contract modification exists when the parties to a contract approve a modification that either creates new or changes existing enforceable rights and obligations of the parties to the contract. A contract modification could be approved in writing, by oral agreement or implied by customary business practices. If the parties to the contract have not approved a contract modification, an entity shall continue to apply this Standard to the existing contract until the contract modification is approved.’ [IFRS 15.18].

The standard goes on to state ‘a contract modification may exist even though the parties to the contract have a dispute about the scope or price (or both) of the modification or the parties have approved a change in the scope of the contract but have not yet determined the corresponding change in price. In determining whether the rights and obligations that are created or changed by a modification are enforceable, an entity shall consider all relevant facts and circumstances including the terms of the contract and other evidence.’ [IFRS 15.19]. If the parties to a contract have approved a change in the scope of the contract but have not yet determined the corresponding change in price, an entity shall estimate the change to the transaction price arising from the modification in accordance with the requirements for estimating and constraining estimates of variable consideration. [IFRS 15.19].

These requirements illustrate that the Board intended these requirements to apply more broadly than only to finalised modifications. That is, IFRS 15 indicates that an entity may have to account for a contract modification prior to the parties reaching final agreement on changes in scope or pricing (or both). Instead of focusing on the finalisation of a modification, IFRS 15 focuses on the enforceability of the changes to the rights and obligations in the contract. Once an entity determines the revised rights and obligations are enforceable, it accounts for the contract modification. Contract terminations (either partial or full) are also considered a form of contract modification under IFRS 15.

The standard provides the following example to illustrate the accounting for an unapproved modification. [IFRS 15.IE42-IE43].

Once an entity has determined that a contract has been modified, the entity determines the appropriate accounting treatment for the modification. Certain modifications are treated as separate stand-alone contracts (discussed at 2.4.1 below), while others are combined with the original contract (discussed at 2.4.2 below) and accounted for in that manner. In addition, an entity accounts for some modifications on a prospective basis and others on a cumulative catch-up basis. The Board developed different approaches to account for different types of modifications with an overall objective of faithfully depicting an entity’s rights and obligations in each modified contract. [IFRS 15.BC76].

The following figure illustrates these requirements.

Figure 28.1: Contract modifications

When determining how to account for a contract modification, an entity must consider whether any additional goods or services are distinct, often giving careful consideration to whether those goods or services are distinct within the context of the modified contract (see 3.2.1 below for further discussion on evaluating whether goods or services are distinct). That is, although a contract modification may add a new good or service that would be distinct in a stand-alone transaction, that new good or service may not be distinct when considered in the context of the contract, as modified. For example, in a building renovation project, a customer may request a contract modification to add a new room. The construction firm may commonly sell the construction of an added room on a stand-alone basis, which would indicate that the service is capable of being distinct. However, when that service is added to an existing contract and the entity has already determined that the entire project is a single performance obligation, the added goods or services would normally be combined with the existing bundle of goods or services.

In contrast to the construction example (for which the addition of otherwise distinct goods or services are combined with the existing single performance obligation and accounted for in that manner), a contract modification that adds distinct goods or services to a single performance obligation that comprise a series of distinct goods or services (see 3.2.2 below) is accounted for either as a separate contract or as the termination of the old contract and the creation of a new contract (i.e. prospectively). In the Basis for Conclusions, the Board explained that it clarified the accounting for modifications that affect a single performance obligation that is made up of a series of distinct goods or services (e.g. repetitive service contracts) to address some stakeholders’ concerns that an entity otherwise would have been required to account for these modifications on a cumulative catch-up basis. [IFRS 15.BC79].

As illustrated in Example 28.12 at 2.4.2 below, a contract modification may include compensation to a customer for performance issues (e.g. poor service by the entity, defects present in transferred goods). An entity may need to account for the compensation to the customer as a change in the transaction price (see Chapter 29 at 3.5) separate from other modifications to the contract.

2.4.1 Contract modification represents a separate contract

Certain contract modifications are treated as separate, new contracts. [IFRS 15.20]. For these modifications, the accounting for the original contract is not affected by the modification and the revenue recognised to date on the original contract is not adjusted. Furthermore, any performance obligations remaining under the original contract continue to be accounted for under the original contract. The accounting for this type of modification reflects the fact that there is no economic difference between a separate contract for additional goods or services and a modified contract for those same items, provided the two criteria required for this type of modification are met.

The first criterion that must be met for a modification to be treated as a separate contract is that the additional promised goods or services in the modification must be distinct from the promised goods or services in the original contract. This assessment is done in accordance with IFRS 15’s general requirements for determining whether promised goods or services are distinct (see 3.2.1 below). Only modifications that add distinct goods or services to the arrangement can be treated as separate contracts. Arrangements that reduce the amount of promised goods or services or change the scope of the original promised goods or services cannot, by their very nature, be considered separate contracts. Instead, they are modifications of the original contract (see 2.4.2 below). [IFRS 15.20(a)].

The second criterion is that the amount of consideration expected for the added promised goods or services must reflect the stand-alone selling prices of those promised goods or services at the contract modification date. However, when determining the stand-alone selling price entities have some flexibility to adjust the stand-alone selling price, depending on the facts and circumstances. For example, a vendor may give an existing customer a discount on additional goods because the vendor would not incur selling-related costs that it would typically incur for new customers. In this example, the entity (vendor) may determine that the additional transaction consideration meets the criterion, even though the discounted price is less than the stand-alone selling price of that good or service for a new customer. In another example, an entity may conclude that, with the additional purchases, the customer qualifies for a volume-based discount (see 3.6.1.E and 3.6.1.G below on volume discounts). [IFRS 15.20(b)].

The following example illustrates considerations for determining whether the amount of consideration expected for the additional goods and services reflects the stand-alone selling price:

In situations with highly variable pricing, determining whether the additional consideration in a modified contract reflects the stand-alone selling price for the additional goods or services may not be straightforward. Entities need to apply judgement when making this assessment. Evaluating whether the price in the modified contract is within a range of prices for which the goods or services are typically sold to similar customers may be an acceptable approach.

The following example illustrates a contract modification that represents a separate contract. [IFRS 15.IE19-IE21].

2.4.2 Contract modification is not a separate contract

If the criteria discussed at 2.4.1 above are not met (i.e. distinct goods or services are not added or the distinct goods or services are not priced at their stand-alone selling price), the contract modifications are accounted for as changes to the original contract and not as separate contracts. This includes contract modifications that modify or remove previously agreed-upon goods or services or reduce the price of the contract. An entity accounts for the effects of these modifications differently, depending on which of the following three scenarios ((A)-(C) below) described in paragraph 21 of IFRS 15 most closely aligns with the facts and circumstances of the modification. [IFRS 15.21].

- If the remaining goods or services after the contract modification are distinct from the goods or services transferred on, or before, the contract modification, the entity accounts for the modification as if it were a termination of the old contract and the creation of a new contract.

The amount of consideration to be allocated to the remaining performance obligations (or to the remaining distinct goods or services in a single performance obligation identified in accordance with paragraph 22(b) of IFRS 15, see 3.2.2 below) is the sum of:

- the consideration promised by the customer (including amounts already received from the customer) that was included in the estimate of the transaction price and that had not been recognised as revenue; and

- the consideration promised as part of the contract modification.

For these modifications, the revenue recognised to date on the original contract (i.e. the amount associated with the completed performance obligations) is not adjusted. Instead, the remaining portion of the original contract and the modification are accounted for, together, on a prospective basis by allocating the remaining consideration (i.e. the unrecognised transaction price from the existing contract plus the additional transaction price from the modification) to the remaining performance obligations, including those added in the modification.

Example 28.11 from the standard illustrates the accounting for a contract modification of a services contract that is determined to be a series of distinct goods or services (see 3.2.2 below) and meets the criteria in paragraph 21(a) of IFRS 15 to be accounted for as a termination of the existing contract and the creation of a new contract. As the performance obligation is a series, the services provided after the contract modification are distinct from those provided before the contract modification. [IFRS 15.IE33-IE36].

The following example from the standard also illustrates a modification that is treated as a termination of an existing contract and the creation of a new contract. [IFRS 15.IE19, IE22-IE24].

In Example 28.12 above, the entity attributed a portion of the discount provided on the additional products to the previously delivered products because they contained defects. This is because the compensation provided to the customer for the previously delivered products is a discount on those products, which results in variable consideration (i.e. a price concession) for them. The new discount on the previously delivered products was recognised as a reduction of the transaction price (and, therefore, revenue) on the date of the modification. Changes in the transaction price after contract inception are accounted for in accordance with paragraphs 88-90 of IFRS 15 (see Chapter 29 at 3.5).

In similar situations, it may not be clear from the change in the contract terms whether an entity has offered a price concession on previously transferred goods or services to compensate the customer for performance issues related to those items (that would be accounted for as a reduction of the transaction price) or has offered a discount on future goods or services (that would be included in the accounting for the contract modification). An entity needs to apply judgement when performance issues exist for previously transferred goods or services to determine whether to account for any compensation to the customer as a change in the transaction price for those previously transferred goods or services.

- The remaining goods or services to be provided after the contract modification may not be distinct from those goods or services already provided and, therefore, form part of a single performance obligation that is partially satisfied at the date of modification.

If this is the case, the entity accounts for the contract modification as if it were part of the original contract. The entity adjusts revenue previously recognised (either up or down) to reflect the effect that the contract modification has on the transaction price and updates the measure of progress (i.e. the revenue adjustment is made on a cumulative catch-up basis). This scenario is illustrated, as follows. [IFRS 15.IE37-IE41].

- Finally, a change in a contract may also be treated as a combination of the two: a modification of the existing contract and the creation of a new contract.

In this case, an entity would not adjust the accounting treatment for completed performance obligations that are distinct from the modified goods or services. However, the entity would adjust revenue previously recognised (either up or down) to reflect the effect of the contract modification on the estimated transaction price allocated to performance obligations that are not distinct from the modified portion of the contract and would update the measure of progress.

2.4.3 Application questions on contract modifications

See 2.2.1.D above for a discussion on how an entity would account for a partial termination of a contract (e.g. a change in the contract term from three years to two years prior to the beginning of year two). See Chapter 32 at 2.1.6.E for a discussion on how an entity would account for a contract asset that exists when a contract is modified if the modification is treated as the termination of an existing contract and the creation of a new contract.

2.4.3.A When to evaluate the contract under the contract modification requirements

An entity typically enters into a separate contract with a customer to provide additional goods or services. Stakeholders had questioned whether a new contract with an existing customer needs to be evaluated under the contract modification requirements.

A new contract with an existing customer needs to be evaluated under the contract modification requirements if the new contract results in a change in the scope or price of the original contract. Paragraph 18 of IFRS 15 states that ‘a contract modification exists when the parties to a contract approve a modification that either creates new or changes existing enforceable rights and obligations of the parties to the contract’. [IFRS 15.18]. Therefore, an entity needs to evaluate whether a new contract with an existing customer represents a legally enforceable change in scope or price to an existing contract. A legally enforceable change in scope or price to an existing contract could also be accomplished by terminating the existing contract and entering into a new contract with the same customer. In those situations, entities also need to consider the contract modification requirements in IFRS 15.

In some cases, the determination of whether a new contract with an existing customer creates new or changes existing enforceable rights and obligations is straightforward because the new contract does not contemplate goods or services in the existing contract, including the pricing of those goods or services. Purchases of additional goods or services under a separate contract that do not modify the scope or price of an existing contract do not need to be evaluated under the contract modification requirements. Rather, they are accounted for as new (separate) contract.