CHAPTER 1

Own Good Businesses

________________

Business Ownership

The best way to build wealth is through business ownership. Think of some wealthy individuals. Most of them probably became wealthy by owning and operating a business. Even some of the most famous actors, singers, and athletes end up generating more wealth after their careers end by using their fame as a platform to start a business. Don't be concerned if you can't think of a lucrative business of your own to start. Become an owner of an already successful business that someone else founded! Owning shares in a company could potentially be as good as if you started the business yourself, but with significantly less effort. For anyone who has money to invest, share ownership (also referred to as stock or equity ownership) provides them with an opportunity to be a business owner. You may be surprised at how little money it takes to get started. This makes stock ownership the great equalizer when it comes to wealth creation. Accordingly, this book is focused on equity (stock) investing. If you start investing at an early age, owning good businesses for an extended period of time could be all you need to build significant wealth. Having a long time horizon makes wealth accumulation easier, but even if you only have a shorter time period the power of investing can still have a positive impact on your financial health. Financial securities that do not provide business ownership, such as bonds, are not addressed in this book, but it is important to note that these securities may have a place in your portfolio as well, depending on your personal situation.

Active versus Passive Investing

Even though they are popular among investors, we do not discuss index funds or exchange-traded funds (ETFs) in great detail. The reason for this is that index funds and ETFs are (primarily) passive investments that track the performance of a stock market index or sector with no consideration given to the quality of the underlying businesses. There are a number of actively managed ETFs available where the manager tries to own only good businesses, but I would urge investors to distinguish between active and passive investing and to fully understand the investment strategy being employed before investing.

While an index fund is a form of mutual fund, an ETF is essentially a cross between a mutual fund and a stock. Like a mutual fund, ETFs usually represent ownership in a group of companies from a specific region, country, sector, industry, or broad stock market index (such as the S&P 500, Nikkei 225 or MSCI World Index). However, while mutual funds tend to have higher fees and are bought and sold directly through a broker or the fund's manager, ETFs usually have low fees and are bought and sold on an exchange in the same way a stock is traded, making it easier and faster to buy and sell them. Today, there is an ETF for almost every type of investment imaginable, including bond indices, market sectors, commodities, and investment styles (like value or growth), as well as more obscure financial concepts, such as volatility.

The reason I exclude passive investments from this book is that they represent most or even all the companies in a specific group, which means you are buying the worst as well as the best businesses when you buy a passive ETF or index fund. Why would you want to invest any of your hard-earned money into substandard businesses if you do not have to? Active investment managers, on the other hand, try to separate stock market constituents into two baskets, the best opportunities and then everything else. In some cases, passive investments may be an investor's only option since investing in individual securities or an actively managed fund may not be possible or may be prohibitively expensive.

Furthermore, many indices, like the S&P 500, Euro Stoxx 600, or Nikkei 225, are market-capitalization-weighted, which means that a stock's weight in the index is determined by its size. The larger the company, the bigger it is as a portion of the index. ETFs that track these indices are therefore subject to concentration risk. As investors pile into an ETF, they force additional buying of the constituent companies, with most of the money (on average) going to the stocks with the highest market values. A rapid increase in the price of a stock can cause the stock's weight in the ETF to become excessive. This is okay as long as the stock's price keeps rising, but when it falls, look out below.

A prime example of concentration risk in an ETF involves GameStop Corp. During the global pandemic, GameStop reached a low of $2.57 on April 3, 2020, in part driven down by short sellers. A short seller is an investor who borrows shares in a company and sells them, with the intention of buying them back in the future at a lower price and returning the borrowed shares. The short seller thinks that the price of the stock is too high and that it will fall in the near future. However, GameStop became popular as a “meme” stock, and private investors aggressively bought the company's shares, driving up the price and forcing the short sellers to cover their short positions (buy back the shares they had borrowed) at higher and higher prices. Meme stocks are stocks that become popular on social media where investors share stories about stocks that are sometimes, but not always, based on fact. The combination of investors buying the shares to own them and short sellers buying to cover their positions can lead to a sudden surge in prices and trading volume, which is known as a “short squeeze.” In the case of GameStop, the short squeeze caused the share price to jump as high as $347.51 when the markets closed on January 27, 2021. GameStop represented just over 1% of a popular retail sector ETF on April 3, 2020, but this rapid jump in share price increased the company's weight in the ETF to nearly 20% on January 27, 2021. A careless investor buying this ETF on January 27 would not realize that close to 20% of their money was being used to buy shares of GameStop at an incredibly expensive valuation.1 This example also serves to highlight the growing importance of social media in investing and the risk of being short a stock that has the potential of experiencing a short squeeze. I discuss short selling more in Chapter 20, along with other advanced investment strategies, but would warn readers that short selling introduces new risks into your portfolio and should only be attempted after careful consideration by experienced investors.

Active investment management conducted in the manner described in this book can outperform passive investment strategies in the long run. Accordingly, this book is intended for investors who agree that the best way to build wealth is through ownership of good businesses, whether they invest for themselves, or they employ an active investment manager.

The Pitfalls of Investing

At its core, equity investing is simple: own good businesses in growing industries and buy them at attractive prices. This investment process, also referred to as “value investing,” reflects the investment philosophies shared by many of the world's most renowned investors, such as Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett, Howard Marks, Seth Klarman, Joel Greenblatt, and Jeremy Grantham. If we own businesses that are difficult to replicate, difficult to compete with, and that provide services and products that are difficult to live without, we can generate significant wealth over time and protect our portfolio from losses during periods of market weakness. Value investing does not restrict one to owning businesses that are not growing. Value investing refers to ensuring that you are not overpaying for the business and that you are getting good value for what you pay. Shares of companies that cannot grow are often inexpensive and will likely stay that way, earning them the nickname “value traps.”

Investing in good businesses involves a straightforward process, but it is not easy. The reality is that investing successfully is a complex and time-consuming task. To understand the myriad factors that can affect the performance of an investment, investors must be voracious readers and pay close attention to market and industry developments. Not only are investors required to assimilate vast amounts of data but they must also quickly understand the context and implications of new information. This is what Howard Marks refers to as “second-level thinking” in his book The Most Important Thing. For the global investor who must monitor the entire world, the job of gathering and analyzing market data is significantly more challenging. Despite the work required, investors who are keen to take advantage of all the world's financial markets have to offer will find it to be a worthwhile endeavor. Whether we recognize it as individuals or not, we live in a global financial system. Businesses that we would consider domestic or local can be affected by developments that take place on the other side of the world. In this sense, any investor will benefit by staying informed of events that occur in other regions of the world. By thinking and acting globally, any investor will be better equipped to understand and mitigate risks in their portfolio, whether they invest globally or not.

Staying objective and having the ability to effectively filter out inconsequential information or “noise” when monitoring the global markets is an essential but difficult task for investors. All human beings are subject to certain instincts (commonly referred to as behavioral biases) that make the seemingly simple task of investing very challenging. As humans evolved as a species, we developed fixed patterns of behavior designed to ensure our survival. While these instincts help us survive, they can make us fail miserably at investing. A splendid example is our preference to be part of a larger group and follow the crowd; after all, there is safety in numbers. Wandering off on your own to hunt for food was risky for the earliest humans, a fact that led us to be hard-wired to associate with other people. It is psychologically challenging to invest in a way that you know is contrary to the crowd and goes against what you are reading and hearing from other investors. It is for this reason that truly contrarian investors are so scarce, and often so successful.

Confirmation bias is another instinct we need to overcome. It causes us to downplay facts that conflict with our existing beliefs about a company and instead focus on things that support what we already believe to be true. Part of the reason we do this is that we tend to believe that other people think the way we do. It is important to avoid making this assumption because people often do not think alike, and eventually business fundamentals will prevail. A company in a fast-growing industry may perform well for a while even if its technology or product offering is inferior to that of its competitors. However, a company's competitive positioning will eventually determine how its share price performs. Numerous examples of this occurred in the tech bubble. Many technology companies (including anything with a “.com” attached to its name) saw their share prices increase significantly in the late 1990s even though their longer-term business prospects were mediocre at best. Once investors came to their senses in the early 2000s and business fundamentals once again mattered, many of these companies failed.

Without exception, the noise investors are subjected to at market peaks is universally positive, which makes it difficult for them to sell stocks and lock in profits, exactly at the time it is most important to do so. Conversely, the commentary at market bottoms is universally negative, which makes it hard to buy stocks at precisely the moment you should buy aggressively. Of course, there are many other forms of behavioral biases. These include a reluctance to take a loss on an investment and the related desire to break even on a trade, which often causes investors to hold on to losing trades far longer than they should, eventually leading them to sell at an even greater loss. As people, we also typically prefer to invest in companies we are already familiar with, which results in a home bias. This means we tend to invest predominately in companies that we know and use on a regular basis and do not look further afield, even though better investment opportunities may be out there. This is not to suggest that you should invest in a business you do not fully understand, simply that you look beyond your immediate region when deciding which businesses to invest in. If this book can accomplish one thing, my hope is that it helps investors overcome their home bias and look objectively for the best investment opportunities from around the world.

In my experience, the most common mistakes made by investors (professional or otherwise) include an underappreciation of business risks, overpaying for a business, focusing on short-term share price movements instead of long-term earnings fundamentals, and not considering the full set of global investment opportunities available to them. Last, a lack of preparation and forethought that considers how businesses perform in various stages of the economic cycle, and how their share prices behave in various stages of the market cycle, can lead investors to react emotionally and make poor investment decisions.

The first step to beating the odds and overcoming these pitfalls is to train yourself to think like a business owner. Thinking of your investments as businesses, rather than numbers on a page, changes the way you respond to unwelcome events and will naturally allow you to take a longer-term view, improving your chances for success in the process. If you spent your lifetime building a great business, would you sell it in the midst of a recession at a “fire-sale price” if you were confident the business would fully recover and continue to grow? Definitely not. It is true that you would not have spent a lifetime building the business if you acquired ownership by buying its common shares, but the financial consequences would be similar. The simple fact that share prices can deviate significantly from the true value of the business is why public equity markets are indispensable for building wealth. When share prices fall to fire-sale prices, buy ownership in good businesses.

Characteristics of a Good Business

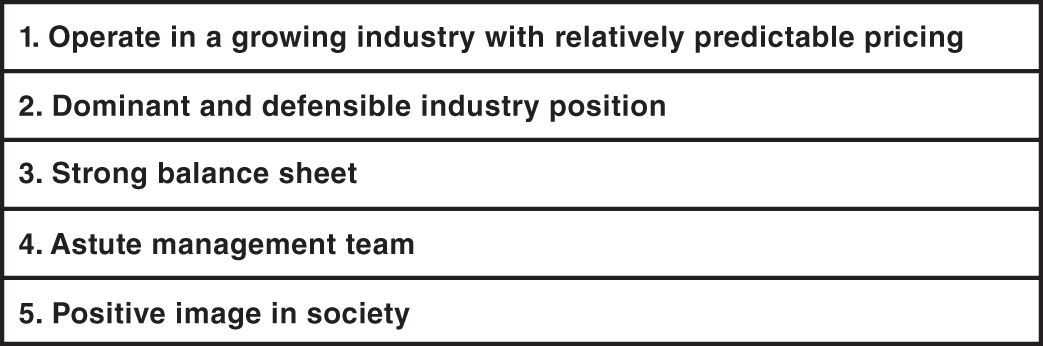

If someone asked you to define a “good business,” what would you say? It seems like a straightforward question, but the more specific our answer needs to be the more challenging it becomes, and not everyone would answer this question in the same way. Furthermore, the most important business fundamentals vary significantly between different industries, so the characteristics of a good business will change depending on the industry in which it operates. This chapter is meant to provide the reader with a general overview of what attributes are present in all good businesses. Since there are many other success factors that vary by industry, we will elaborate on specific industries in greater detail in Chapters 9 through 19. This chapter provides an overview of what typically makes a company a sound investment regardless of the industry it operates in. What do I mean by a “good business”? Good businesses have the following common attributes:

Operating in a growing industry with relatively predictable pricing helps the management team plan effectively and provides a greater opportunity to grow the business. This does not mean that earnings cannot be cyclical (meaning they are dependent on where we are in the economic cycle), but we must have a sound understanding of how earnings are generated and have the ability to predict with some certainty what the company's earnings will be based on expected economic conditions. This trait is usually associated with stable political, regulatory, and competitive environments.

A dominant and defensible position within an industry is usually evidenced by a stable or growing market share and industry-leading profitability that is driven by a sustainable competitive advantage. This competitive advantage could come from a superior product or service, more efficient distribution channels, scale of operations, manufacturing knowledge, lower material costs, brand recognition, or a number of other factors. The best businesses have a distinct advantage that competitors cannot easily overcome.

A strong balance sheet provides financial flexibility, allowing for dividend increases and share buybacks, and also makes it easier for the company to borrow money, refinance, and pay back debt. It also provides protection in economic downturns and allows management to pursue growth opportunities more easily, including expanding into new geographic markets, acquiring other firms, or investing in research and development. Such investments can enable dominant companies to stay in a leading position far into the future.

The best management teams are made up of visionaries who understand their industry and function as good stewards of investor capital, including operating with good governance by employing sound policies and procedures designed to enhance decision making and risk management. They are also astute allocators of capital (they deploy the company's resources in an optimal way) who are able to navigate through tough times and seize opportunities as they arise to enhance shareholder value. Their interests are aligned with those of investors and society.

Having a positive image in society is another important attribute of good businesses. A company's image is no longer just about brand recognition. Corporate policies on social and environmental issues can influence how the company is perceived by consumers, other businesses, and government regulators. For example, having a reputation for being a bad polluter in one market could cause a company to lose customers in other markets. A company's governance structure (how it is governed and managed) can also have an influence on a consumer's decision to buy its products or whether other businesses will choose to engage with the company in business activities. Having business dealings with a company that has a bad reputation can cost a company customers and lost revenue.

Not all these attributes have to be present in equal measure for a company to be a worthwhile investment, but weakness in one or more of them should give you reason to pause and take a closer look. Breaking these five attributes down a bit further, we will take a closer look at the importance of company profitability, earnings sustainability, balance sheet strength, growth prospects, investment risk, valuation, and social factors in Chapter 8 when we discuss company analysis.

Own the Best and Leave the Rest

Given the vast number of publicly traded companies and the large amount of information you need to look at when analyzing them, it is essential that you optimize your time. Create your own process for analyzing a business, prioritizing items that are critical to you as an investor and that can be verified quickly. If these items appear satisfactory, then you can devote more time and delve deeper into the business. If the company does not meet an important criterion (e.g., it does not generate revenue), remove it from consideration and move on to the next opportunity.

There are so many good businesses available around the world that you should only own the best businesses available to you. Buy those businesses that you think have sustainable earnings growth and are priced attractively. If a company you own becomes expensive compared to its historical valuation ranges, versus its peers’ or the market, reassess why you own it and consider switching into another business. Factoring in where we are in the market cycle can also help you make better decisions on when to exit an investment and move into the next wonderful opportunity. We will discuss the importance of market cycles in detail in Chapter 4. Now we turn to explore the global investment opportunity.

Note

- 1. Data sourced from Bloomberg and Yahoo Finance.