CHAPTER 4

The Global Financial Markets

________________

Global Financial Markets

Developments in the global economy, including trade, manifest themselves in the global financial markets. The financial markets are essentially a mathematical version of the world around us, and they are the engine that keeps our modern economy going. The world's equity and debt markets provide capital to the businesses that power the global economy that in turn creates jobs and generates wealth. Efficient stock and debt markets are therefore a vital part of a country's continuing economic development. These markets should be structured and governed in a way that allows capital to flow easily to its most productive use. Regulations must exist and be enforced that protect shareholder rights and ensure that the use of investor capital is adequately rewarded. Also, if foreign capital is needed to allow domestic businesses to flourish, the rights of foreign shareholders must be protected on par with domestic investors. Trust in a country's financial system, the rule of law, and the manner in which business is carried out, is essential for sustainable economic growth in the long run.

Economic growth and development is an aspiration: it is a mechanism to alleviate poverty, to give opportunity to those who do not yet have it, to foster equality, and to create a better society. Well-functioning exchanges enable economic growth and development by facilitating the mobilisation of financial resources—by bringing together those who need capital to innovate and grow, with those who have resources to invest. They do this within an environment that is regulated, secure, transparent and equitable. Exchanges also seek to promote good corporate governance amongst their listed issuers, encouraging transparency, accountability and respect for the rights of shareholders and key stakeholders.

Nandini Sukumar, CEO, the World Federation of Exchanges

All businesses require the reinvestment of capital to survive. The way companies fund their operations often involves using profits generated by the business itself. However, some businesses do not generate sufficient profits to meet their reinvestment needs, whether on a short- or long-term basis. This may be a new business that is growing quickly and needs money in order to fund its growth, or a more mature business that is experiencing a temporary downturn in revenue and needs access to capital to fund operations until the business environment improves. A business requiring an infusion of cash may turn to a bank or private investors or partner with other companies. When these avenues are not an option, however, companies turn to the capital markets for funding. In these instances, the business might borrow the money by issuing debt (bonds) or they might sell ownership in the business by issuing equity (shares). Each of these has different implications, for both the business and the investor.

Debt and equity each represent a claim against the assets and/or cash flow of a business. Debt represents a promise of interest and repayment of one's principal but offers no ownership stake in the business. Conversely, equity represents an ownership stake in the business with no promise of repayment. Shareholders therefore risk the loss of their capital in the event the company falls on hard times, but they also participate more fully in the profits generated by the company. Debt investors are afforded greater protection of their capital and face a lower risk of loss, but they do not participate in the wealth generated by the company to the same extent as shareholders. Both debt and equity provide capital to businesses around the world and are referred to here collectively as the capital markets. Figure 4.1 compares the relative size of the world's equity and bond markets.

FIGURE 4.1 Global Capital Markets (USD Trillions)

Data source: The Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), “Capital Markets Fact Book, 2021,” https://www.sifma.org/resources/research/fact-book/, accessed November 14, 2021.

At the end of 2020, the global bond market consisted of approximately US$123.5 trillion in outstanding debt. Slightly smaller, but still massive, the world's stock markets ended 2020 with a total market capitalization of US$105.8 trillion.1

Much larger than either the debt or equity market are the currency and derivative markets. The Bank for International Settlements estimates the average trading volume to be the equivalent of US$6.6 trillion per day in the foreign exchange (currency) market, which is discussed in detail in Chapter 6. The derivative market is more challenging to quantify, partly because it depends on what is considered to be a derivative. In general terms, a derivative is a financial security whose value or price movement is “derived from” (based on) another asset, such as a currency, bond, stock, index, or commodity. Another challenge to estimating the size of the derivative market is that many derivative products are traded privately, making them exceedingly difficult to track. It is for this reason, as well as their complexity, that Warren Buffett famously referred to derivatives as “financial weapons of mass destruction.” As noted earlier, the best way to build wealth is through business ownership, and the most effective way to build business ownership is through the world's public equity markets.

Global Equity Markets

The trading of public company shares is transacted primarily on more than 80 stock exchanges located around the world. According to the World Federation of Exchanges, “[a] stock exchange is an organised marketplace, licensed by a relevant regulatory body, where ownership stakes (shares) in companies are listed and traded. Listing happens in the so-called ‘primary market,’ where a portion of a company's shares are made available to the public. The company often uses the listing to raise funds through issuing new equity shares. Investors can then buy and sell these listed shares in the so-called ‘secondary market.’ While listing in the primary market may result in a flow of funds from investors to the firm, the trading between investors in the secondary market does not.”2

The Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) estimated the value of all publicly traded equities (their total market capitalization) to be $120.4 trillion (USD) at the end of June 2021. Roughly 43% of that total was based in the Americas, 33% in Asia Pacific, and 24% in the EMEA region (Europe, the Middle East, and Africa). From 2000 to the second quarter of 2021, the highest increase in total market capitalization came from the Asia Pacific region, which grew at a rate of 9.9% annually. In fact, since 2000 emerging economies have grown their share of total global market capitalization from 7.7% to 27%. This rapid growth in market capitalization for the Asia Pacific region was driven in part by an increase in the number of listed companies. Of the roughly 55,000 companies that are listed globally, the Asia Pacific region is home to 57.3% of them, EMEA 23.2%, and the Americas 19.5%.3 With a greater total market capitalization and fewer listed companies, businesses based in the Americas tend to be larger than those in other regions. However, there are large, globally focused businesses to be found in every region of the world and excluding them from investment consideration simply because you are not familiar with them can be a costly mistake. Figure 4.2 shows how the 100 top-performing stocks over the past one, two, three, four, and five years are dispersed by region even after adjusting for currency movements.

Whatever time period you consider, there are stocks in every region of the world that turn out to be among the best performers in any given year. While the relative performance of different regions fluctuates over time, the free flow of investor capital within and between geographic regions will ensure that money will move to wherever the best investment opportunities exist. The growing number of companies listed on stock exchanges, combined with higher average share prices, have caused the dollar volume of shares traded to increase steadily over the years as shown in Figure 4.3, and this trend is likely to continue.

FIGURE 4.2 100 Top-Performing Stocks by Region

Data source: Bloomberg, as of December 17, 2021. Data set includes the largest 3,000 companies globally that have return data available for the stated period. Returns are based in USD.

FIGURE 4.3 Annual Worldwide Equity Trading Volume (Trillions USD)

Data source: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/CM.MKT.TRAD.CD, accessed November 14, 2021.

Figure 4.3 shows how significantly the global equity market has grown over the past few decades. With more than 55,000 companies listed on public stock exchanges worldwide, there are plenty of investment opportunities available to the global investor. In addition to this vast pool of investable businesses, there are new businesses coming to the market every day. There was a total of 1,388 companies that were newly listed on an exchange in 2020, with a total market value of US$236.1 billion. A majority of these businesses were located in emerging markets.4 A tremendous amount of wealth can be created for owners when a company initially lists on an exchange and becomes publicly traded. When a company first decides to make the move from being privately owned to publicly owned, it goes through a process known as an initial public offering (IPO).

Initial Public Offerings

One obvious benefit to taking a company public is that it provides a way for the owners of the business to benefit financially from all the hard work required to build the company. It also enhances the company's profile, provides the company with access to a larger pool of capital, and disperses the ownership of the company among a larger group of investors. The downsides to going public are higher costs as well as greater regulation and scrutiny of the company's operations. Private companies can control who is able to invest in the firm, whereas public companies generally cannot.

Since so much wealth can be realized in the IPO process, it can be difficult for the average investor to take part in an IPO. Demand for shares is often multiple times the number of shares being sold by the company. This means that most of the shares sold in an IPO go to larger investors that are perceived as being more important to the firm that is underwriting (managing) the IPO. Company IPOs that are particularly attractive tend to be in greater demand and therefore are even outside the ability of most institutional investors to participate in to a meaningful extent. All is not lost, however, as there are many companies that continue to grow and create economic wealth long after they go public.

Financial Market Interaction

It is important for investors to understand how different segments of the financial markets interact and can affect one another. Developments in the global bond market, for example, can have a significant impact on equity markets. This means that equity investors must watch the bond market closely. The relative movement of stocks and bonds at any given point in time depends on market conditions and where we are in the market cycle (discussed in Chapter 5). However, in very general terms, when economic conditions deteriorate, bonds tend to outperform equities, and when economic conditions are improving, equities tend to outperform bonds. Watching activity in the bond market can therefore provide valuable insights for you as an equity investor.

Two important things to watch in the bond market are changes in interest rates and changes in credit spreads. Bond prices are heavily influenced by changes in interest rates, which are primarily determined by expectations for economic growth and inflation. Decisions affecting the level of interest rates are made by a country's central bank, and are referred to as “monetary policy.” If the bank is reducing interest rates, the monetary policy is called “accommodative” or “dovish,” and if the bank is raising rates, the monetary policy is referred to as “contractionary” or “hawkish.” As noted earlier, when a central bank wants to generate higher levels of economic growth it lowers interest rates, and when it wants to slow economic growth it raises interest rates. The most influential central banks include the Federal Reserve in the United States, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, and the People's Bank of China. In extreme circumstances like the global financial crisis of 2008, the world's central banks will act in a coordinated fashion to resolve problems faced by the global economy and global financial system.

You may wonder why a central bank would ever want to intentionally reduce economic growth, but the reason is quite simple. Sustaining elevated levels of economic growth may eventually lead to inflation, which can be very damaging to an economy since it erodes the value of most assets and can adversely affect spending decisions for both consumers and businesses. To prevent high levels of inflation, central banks may deliberately try to slow the rate of growth and create a “soft landing” for the economy, which is characterized by a gradual reduction in economic growth. This can be a challenging task for the central bank. If the central bank raises interest rates too slowly, inflation may increase suddenly and become difficult to control. On the other hand, if the bank raises interest rates too quickly, it could create a rapid drop in economic growth and perhaps even cause a recession (defined as two or more consecutive quarters of negative economic growth).

It is important to note that it is changes in inflation and interest rate expectations that drive the financial markets. That is to say, market participants respond to changes in interest rate and inflation expectations, rather than to what the current economic data is showing. Although falling(rising) interest rates are generally good(bad) for equities, economic circumstances may cause investors to react in a seemingly irrational manner. For example, while falling interest rates are generally good for stocks, if a central bank were to unexpectedly announce a decrease in interest rates in an already strong economy, this could be regarded as inflationary and stock prices could actually fall instead of rise. Conversely, a gradual increase in interest rates can be construed as positive for the equity market in cases where economic growth is strong and the risk of inflation is slowly rising.

Credit Spreads

Credit spreads are also important to watch. A credit spread is the difference between the interest rate paid on a corporate bond and the interest rate paid on a “risk-free” government bond with the same term to maturity. For example, a five-year bond issued by a company would typically be compared to a five-year bond issued by the country where the company is located. The difference in the interest rate being paid on the two bonds is called the “spread.” Corporate bonds typically pay a higher rate of interest than government bonds in order to compensate investors for a higher level of risk. In this instance we are referring to default risk, which is the possibility the investor will not receive all of the expected coupon (interest) payments or repayment of principal (the par value of the bond). Government bonds are regarded as risk-free because the chance of default is (usually) exceptionally low, although there have been instances of governments defaulting on their debt. Bonds issued by companies that are perceived to be more likely to default must of course pay investors a higher rate of interest and therefore have higher spreads compared to their lower-risk peers. These bonds are often referred to as high-yield or junk bonds.

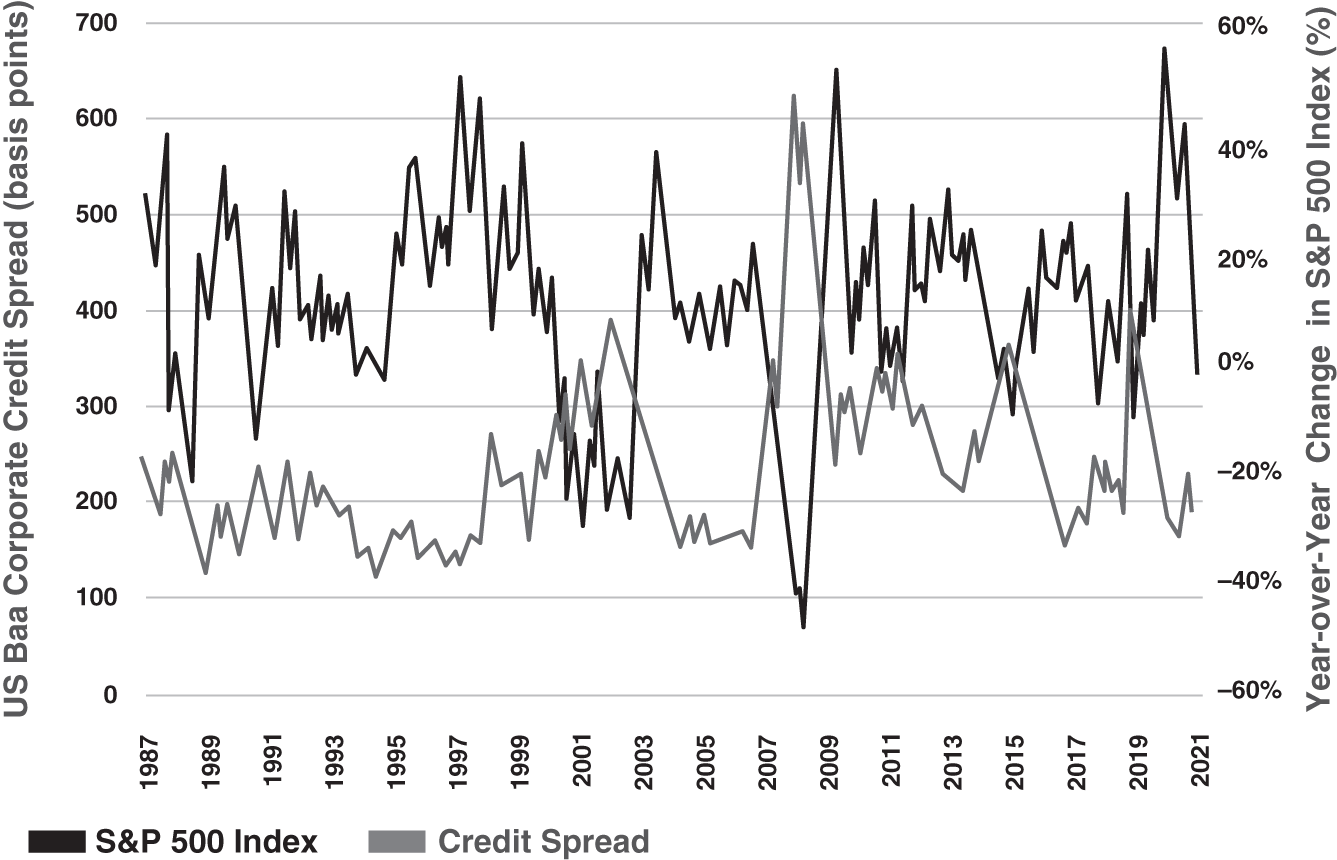

Credit spreads are excellent indicators of investor psychology. When investors are confident that they will get their money back, credit spreads fall since investors are willing to take on more risk and lend money at lower rates. However, as the economy weakens and the risk of lending grows, investors will demand higher returns and the spread will increase. Figure 4.4 shows how credit spreads behave in periods of economic stress, measured as the mid-point of US corporate Baa-rated bonds.

Figure 4.4 illustrates that credit spreads are not constant, but rather change significantly over time. As investors become fearful, credit spreads increase, and as investors become more optimistic, credit spreads fall. Periods of fear and risk aversion are very apparent here, evidenced by the spike in credit spreads in the tech bubble, financial crisis, and the early days of the 2020 global pandemic.

FIGURE 4.4 US Corporate Baa-rated Bond Spread (basis points)

Data source: Bloomberg, as of December 12, 2021.

Higher spreads result in higher financing costs for businesses, which causes companies to reduce spending and for go projects that otherwise might have been profitable with lower financing costs. The impact of changes in interest rates on business activity is therefore ultimately reflected in the equity market. Higher rates eventually reduce business investment and corporate profitability, while lower rates encourage investment, which spurs economic growth and generates additional corporate profits. Naturally, higher expected profits will drive share prices up, while lower expected profits will drive share prices down. The inverse relationship of credit spreads and equity prices is shown in Figure 4.5, which overlays the year-over-year change in the S&P 500 Index price level with the figure on credit spreads presented in Figure 4.4.

As Figure 4.5 shows, credit spreads tend to move in the opposite direction from stock prices, and in fact changes in credit spreads can be a leading indicator for the equity market. The bear markets that began in 2000 and 2007 were both preceded by rising credit spreads. In the case of the 2020 bear market, credit spreads rose only as the market sold off, so they did not function as an early warning sign for equity investors. However, the fact that spreads began to narrow again in late March 2020 supplied some indication that the worst was behind us and that the stock market had already bottomed.

FIGURE 4.5 Credit Spreads and the S&P 500 Index

Data source: Standard & Poor's Financial Services LLC, sourced via Bloomberg, as of May 5, 2022.

Currency Markets

Currency markets also affect equity markets and are therefore important for investors to watch. There have been instances where a rapidly declining currency has spelled serious trouble for local, regional, and even global equity markets. In extreme circumstances, currency crashes can cause equity market corrections. An example is the Asian Financial Crisis that began in 1997, when Thailand decided to no longer peg the Thai baht to the US dollar. The uncertainty and loss of confidence that ensued brought about the devaluation of several regional currencies as well as a subsequent drop in the regions’ stock markets. Actions taken by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank ultimately helped to restore confidence in the region, but not before fear gripped global equity markets and stocks fell around the world, including significant declines in Europe and the United States.

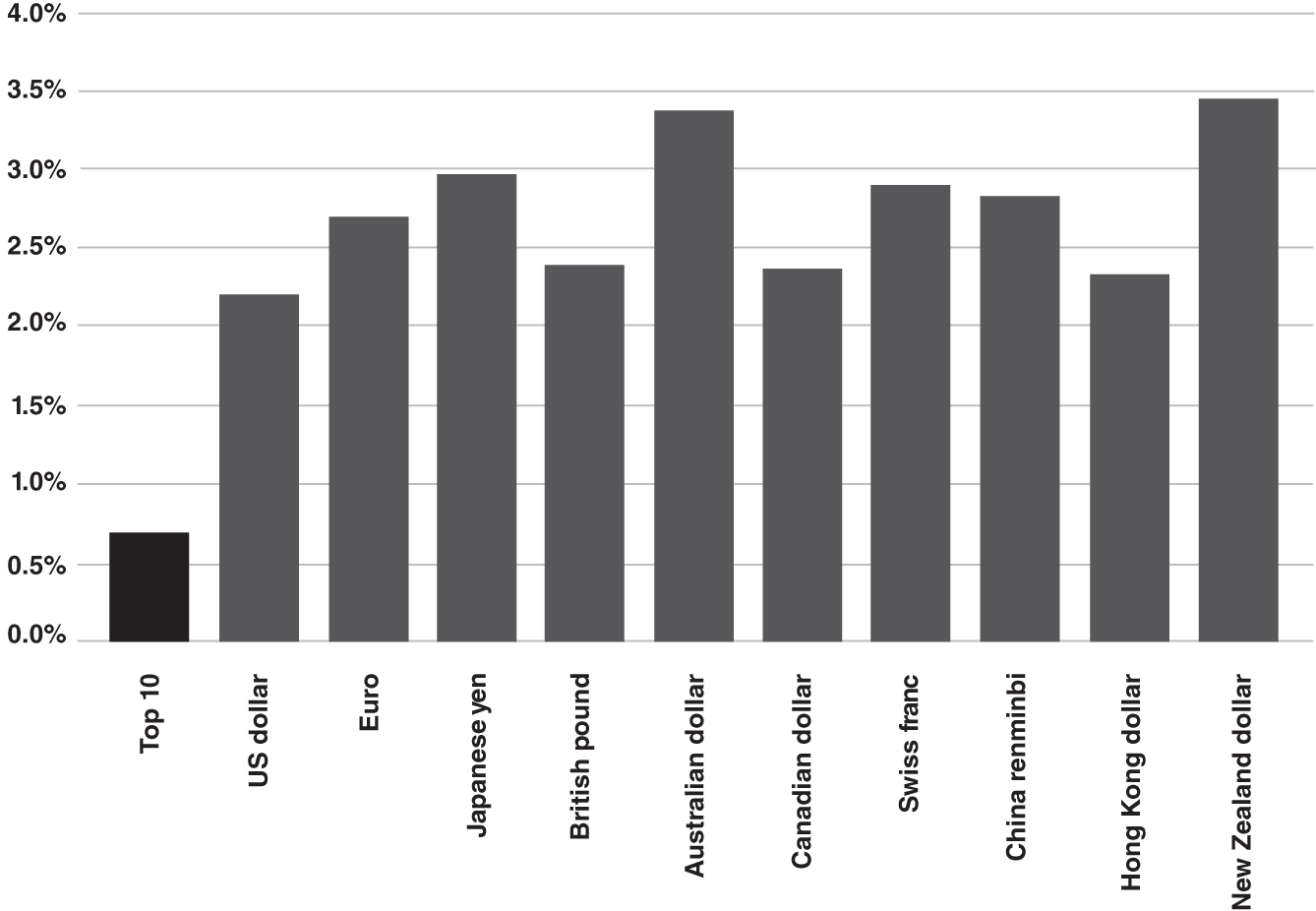

As discussed in Chapter 6, it is best to avoid investing in countries that have excessive levels of external and domestic debt compared to their ability to service that debt. Inflation reduces the value of debt, and so countries with elevated levels of debt have often used inflation to help reduce their debt burden.5 In general, high relative levels of inflation will cause a country's currency to depreciate, so any investment made in that country will most likely fall in value over time based on currency movements alone. However, studies have consistently shown that investing in a basket of different currencies helps to reduce portfolio risk over a long time period. This is clear in Figure 4.6, which shows the degree to which the top 10 currencies in the world fluctuated over a 27-year period compared to an equally weighted basket of all 10 currencies.

Taken individually, the top 10 traded currencies in the world have experienced greater variability in their returns compared to an equally weighted basket of all 10 of the currencies. The reason is fairly simple: the relative price changes of the currencies are not correlated. This means that currencies move in opposite directions at times and therefore owning securities denominated in a mix of foreign currencies will help investors overall and is one of the principal benefits of investing globally. From a US investor perspective, Roger Ibbotson and Gary Brinson found that “unhedged foreign currency exposure provides a buffer against the effects of unexpected changes in U.S. inflation relative to that of other countries.”6 This suggests that investors can protect their portfolios from domestic inflation by maintaining exposure to foreign currencies. Investors can gain exposure to foreign currencies by owning shares of companies domiciled in those countries, either by buying the common shares or a depositary receipt, discussed in greater detail in Chapter 20. The risks associated with investing in foreign currencies and how to manage those risks are discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

FIGURE 4.6 Currency Diversification Reduces Risk

Data source: Bloomberg, as of January 11, 2022. Top 10 currencies referenced are: the US dollar, euro, Japanese yen, British pound, Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, Swiss franc, China renminbi, Hong Kong dollar, New Zealand dollar.

There are tremendous opportunities made possible by the evolutionary nature and machinations of the modern economy, as well as by the always-evolving and interconnected global capital markets. However, with greater rewards comes greater risk. In Part Three we take a close look at the primary risks faced by global investors, namely market cycle, currency, and geopolitical.

Notes

- 1. The Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, “Capital Markets Fact Book, 2021,” https://www.sifma.org/resources/research/fact-book/, accessed November 14, 2021.

- 2. World Federation of Exchanges, “The Role of Stock Exchanges in Fostering Economic Growth and Sustainable Development,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2017.

- 3. The Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, “Global Equity Markets Primer,” https://www.sifma.org/resources/research/insights-global-equity-markets-primer/, accessed November 14, 2021.

- 4. The Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, “Global Equity Markets Primer.”

- 5. Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (Princeton University Press, 2009).

- 6. Roger Ibbotson and Gary Brinson, Global Investing: The Professionals Guide to the World's Capital Markets (McGraw-Hill, 1993), p. 87.