Chapter 16

Shaping and Shape-Shifting Your Organization

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Understanding why organizational structure matters

Understanding why organizational structure matters

![]() Designing an organizational structure that works

Designing an organizational structure that works

![]() Building dynamic capabilities into your organization

Building dynamic capabilities into your organization

Congratulations — you should be close to completing your business plan! You’ve already done the vision thing and data digging to flesh out the details of the many parts of your plan. Now you need to figure out how to organize the parts so they work together as a unified whole. If you need a little nudge, go to Chapter 1 for a refresher on why you started your plan in the first place and the Appendix for an example of a business plan.

Recognizing That Form Follows Function

Your next big step is arranging (or re-arranging) all your company’s resources to put your plan into action. If you wanted to design a house, office, or specialized facility, rather than your company, you likely would consider the words of the famed American architect Louis Sullivan:

Form follows function.

Just because structures are all meant to hold people doesn’t mean that all structures have a similar design. This is why hospitals don’t look like hotels, and hotels aren’t like prisons. If the basic function of each type of structure is different, it requires a different form in order to achieve its purpose.

That form can be as simple as you and a few partners doing everything that needs to be done, sharing files on your laptops. Or it can be as complex as a huge organization with multiple functional areas, scores of offices and factories spread over different continents, and numerous levels of management from a work-team leader on the ground to the CEO at the top.

Many business scholars (oxymoron?) consider the first significant book on strategic management to be Strategy and Structure, published in 1962, which found that organizations that designed a structure first and next created a strategy to fit it were on the road to failure — they were putting the proverbial cart before the horse. In essence, Professor A.D. Chandler Jr., the author, reinforced Louis Sullivan’s mandate that form must follow function. Earlier chapters in this book show how to create your business plan — your function. Here and in Chapter 17, we help you understand what you need to do to carry out your business plan by designing the appropriate form. Let’s get to it.

- Read your company’s mission and vision statements as though you’re seeing them for the first time. (Check out Chapters 3 and 4 for vision and mission statement info.)

- Consider the goals and objectives that you set for your company. (See Chapter 4 for help.)

- Review the strengths and weaknesses of your business, and consider what they say about your company’s opportunities and capabilities. (Chapter 10 helps you look at your company objectively.)

- Think about the ways in which your company provides value to customers. (Chapters 6 and 7 show you how to assess your markets.)

Putting Together an Effective Organization

Where do you start? You can slice and dice the basic components of your organization in several ways. Two sometimes contradictory purposes, however, usually dictate the logic: effectiveness and efficiency — that is, doing the right things versus doing things right (we first discuss these in Chapter 4). The following sections cover the most common structures that result from how you manage this trade-off.

Choosing a basic design

If you are a new or small company, the simplest way to organize is to put a trusted person at the top — the founder if a start-up, an owner or talented manager if the organization is compact — and have everybody else do whatever needs to get done. The “lean” start-up has become a cliché by now. Efficiency and effectiveness are rolled into one due to size. If there’s a need to discuss a problem or report on some new data, no problem. All hands on deck; just call everyone together and start talking. So what then are the trade-offs of tiny-ness? Here are the pros and cons:

- Advantages: You can usually get someone to do a job whenever it needs to be done. Because everyone is together most of the time, and face-to-face communication is relatively easy, all of the staff quickly coalesces around priorities. The design is cost-effective.

Disadvantages: The basic design works best only if your company has a few people. If your company is any larger, the person at the top finds it more difficult to keep track of everybody. It’s harder to do an all-hands-on-deck when the staff starts to get spread over multiple sites, even with the use of online conferencing tools.

The basic design isn’t always efficient. More voices can lead to personal conflicts and clashes of communication style. When the small firm begins to expand is when danger signals usually arise. Whether or not folks realize it, they are, in fact, creating the cultural norms that will identify the firm in the future. Tread carefully.

The basic design isn’t always efficient. More voices can lead to personal conflicts and clashes of communication style. When the small firm begins to expand is when danger signals usually arise. Whether or not folks realize it, they are, in fact, creating the cultural norms that will identify the firm in the future. Tread carefully.

Focusing on a functional model

Business success typically results in organizational growth, including in head count and the variety of tasks that need to be done. This growth tends to happen more with firms making tangible products than with digital enterprises; the personnel-to-revenue ratio of the latter is typically much less as scaling is built into platform software. Yet, for both kinds of firms, product or service providers, the effectiveness versus efficiency trade-off becomes more apparent. Let’s investigate.

If you organize your company around business functions, you divide people into groups that center on what activity they do. You take all the engineers and put them together in one area, lump the marketing geniuses in another, and so on. You still need to make sure that some sort of general manager coordinates the various activities of the functional groups, of course. Here’s how this method stacks up:

- Advantages: A functional organization works well if your business involves only one type of product or service and if the business outlook is stable for the foreseeable future. The organization is efficient, because people excel at their particular tasks, and they perform each function in only one place, creating opportunities for scale benefits. Also, every employee knows exactly what they are responsible for and the metrics by which their performance is evaluated.

Disadvantages: Unfortunately, a functional organization can easily turn into a bunch of separate silos standing side by side. The silos, each housing a different functional area, can be difficult to connect together. Operations, for example, wants to make the same single product over and over again, whereas Marketing wants to sell different products to different customers. Each function may be efficient by itself, but the functions taken together aren’t terribly flexible or effective.

Disadvantages: Unfortunately, a functional organization can easily turn into a bunch of separate silos standing side by side. The silos, each housing a different functional area, can be difficult to connect together. Operations, for example, wants to make the same single product over and over again, whereas Marketing wants to sell different products to different customers. Each function may be efficient by itself, but the functions taken together aren’t terribly flexible or effective.This is particularly true when markets shift and changes are necessary: Each different functional area fights to isolate itself, casting blame on others and resisting outside intervention. Your general managers have to shoulder the responsibility of keeping communication open. Not easy.

Divvying up duties with a divisional form

If your company is big enough to be in more than one business, the best approach may be to organize by divisions based on a variable other than functional activity, such as a particular product, or a market, or a geographic area. If your company is huge and diversified, your divisions may cover strategic business units, or SBUs, which are specific product-market combinations. (Refer to Chapter 15 for additional information on SBUs.) Here are the pros and cons:

Advantages: An organization made up of divisions that you base on products, markets, or SBUs encourages you to focus all your energy and resources on the real businesses you’re in. Managers inside the divisions can concentrate on their own customers, competitors, and problems, and each can respond more quickly to market signals. This leads to better effectiveness.

Top-level managers at HQ can oversee how the divisions work together and maintain basic coordination from there. HQ also can transfer promising divisional staff to other divisions, creating opportunities for lower and mid-level staff to develop and expand their managerial skills and competencies. This allows for in-house promotional ladders rather than having to recruit external candidates for higher-level responsibilities — and depressing current staffers who feel passed over.

Top-level managers at HQ can oversee how the divisions work together and maintain basic coordination from there. HQ also can transfer promising divisional staff to other divisions, creating opportunities for lower and mid-level staff to develop and expand their managerial skills and competencies. This allows for in-house promotional ladders rather than having to recruit external candidates for higher-level responsibilities — and depressing current staffers who feel passed over.Disadvantages: Because the separate divisions within your company often represent entire businesses, they sometimes compete with one another, fighting over scarce resources from HQ, and sometimes even over the same customers. In the worst case, the company risks becoming little more than a loose federation of parts rather than a singular and focused enterprise.

Also, separate divisions usually mean replication of overhead costs, because each division invariably has its own set of overlapping management layers and business functions (research, operations, marketing, service, sales, and finance). As a result, your company becomes less efficient.

Sharing talents with the matrix format

The functional and the divisional forms of organizational structure are based on effectiveness (the scope of your operations) versus efficiency variables (that is, their scale). For many organizations, especially ones competing in international markets, a matrix format is a superior way to structure. In a matrix organization, everybody works under two centers of authority and basically wears two hats. One hat may be functional: A person may be in field sales, reporting to the regional manager responsible for all functions in the area. But another hat is divisional: The product division managers at company HQ have control of their products wherever they may be sold, so that the field sales guy also has to report to them on some issues. At least the theory says this is the best way to structure the firm when its activities are so diffuse. Let’s see the pros and cons:

- Advantages: The logic of the matrix format is that separating responsibilities by function creates focused effectiveness; doing so by division generates scaled efficiency; and bringing them together in a matrix structure gives you the best of both worlds.

- Disadvantages: A matrix organization can be tricky to manage — and sometimes even disastrous. The format violates an important management rule: Don’t give people two bosses at one time. Tension is bound to occur between the manager responsible for a given product or service, and the functional manager who oversees a given task. Each of these people might have their own incentives. The production manager at division HQ might want the field salesperson to sell, sell, sell — and thus drive up volume and generate scale savings in production. The area sales manager, on the other hand, might want that field salesperson to sell anything to a local customer, as overall sales volume is what gets them a bonus. The poor guy in the field is caught between two competing forces, and it’s sometimes easy for the wrong one to triumph.

Dealing with too many chefs in the kitchen

The number of tiers in the management cake depends a great deal on how big your company is and how you organize it. In the earlier section “Choosing a basic design,” we explain the benefits of smallness in an organization — the ability to communicate to everyone at once and rapidly mobilize all resources toward goal achievement. But as the firm begins to grow, managers can handle only so many people directly if they want to do a good job.

One way to deal with this is through technology: robotics and AI (artificial intelligence programs that set standards and make decisions). Although still in its infancy, this trend has the potential to radically alter the role of the middle manager — if not absolutely obliterate it. And don’t forget another trend: remote work (WFH, work-from-home). This, too, will present challenges for firms as they grow.

Some organizations have grown without installing layers of managerial oversight — because the nature of the work is one in which individual creativity is critical. In work environments like universities, research labs, and the creative industries, personnel desire autonomy above any other benefit, including salary. In these cases, an increase in company size might not necessitate more managers: The span of the control number is already high (that is, number of workers to managers), and close supervision doesn’t appear to effect results that much. In fact, it may be counterproductive.

- The more control is given to lower levels of company management

- The longer it takes and the harder it is for information to reach top management

- The less flexible your organization is in the face of change

Finding what’s right for you

This is a classic pathology of entrepreneurs, by the way. The personality traits that drive success — single-mindedness, ambition, persistence — can get in the way after a corner has been turned. Close attention to detail can become control freakishness; strong self-confidence can become an unwillingness to let go and allow others to decide. Similar problems often impact family business firms. The founder may want to create a legacy for the children, which is both understandable and good. But family dynamics can be brutal if they aren’t acknowledged and managed before they interrupt sound business planning and decision-making.

Thinking and Organizing for the Future

This chapter has given you numerous ideas and guidelines for structuring your business if it’s a new venture, or reshaping it when your markets shift. We also emphasize that change — constant change — is the new normal as we continue to grope our way through a worldwide Industrial Revolution (see Chapter 13 for more on this topic).

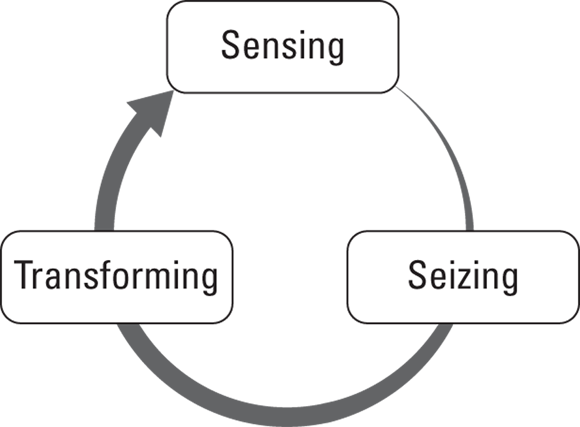

A powerful new model for dealing with change is called “dynamic capabilities.” This approach was designed specifically for organizations faced with constant change and consists of three components (see Figure 16-1):

- Sensing: This is the first step and focuses on how organizations can detect future trends that will have a major impact on their business.

- Seizing: Step two pertains to the methods by which a firm can capture value from the trends before competitors move in.

- Transforming: The last step addresses the fact that the speed of change is not about to slow down anytime soon, and provides guidance on how a firm can best organize itself to be agile and prepared to move quickly when the next opportunity knocks or major threat looms.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 16-1: Dynamic capabilities.

Chapter 13 provides insight about how to peer through the gray clouds to see what might lie beyond. For example, who do you have overseeing a digital strategy or monitoring new ideas on the Internet — some office bureaucrat who’s still learning to surf the web, or a kid who actually lives on the web daily? Who allocates resources to new ideas that might pop up — someone intimately connected to another part of your organization who might see the new idea as a threat to their position of authority?

Chapter 10 raises the concept of a business model — that is, just how a firm can capitalize on its unique advantages to create value. If your firm can spot a new trend before the competition, what’s the point if you can’t rapidly own it before the others move in? Can you overcome internal resistance to abandoning the old model and adapting to the new?

We think the dynamic capabilities model is a nifty way to weave together the key components necessary to succeed in the hyper-charged global economy of the 21st century. Give thought to how you can adapt your own organization to sense, seize, and transform — and do it again and again and again. The key? Organizational leadership, our friend, leadership. Go directly to Chapter 17.

You spell out what your company intends to do — its function — in your business plan. Now you must design a form for your company to support that function. The form your company takes consists of two basic interacting components: people and technology, the latter being machinery, communication devices, software programs, tools, and so on.

You spell out what your company intends to do — its function — in your business plan. Now you must design a form for your company to support that function. The form your company takes consists of two basic interacting components: people and technology, the latter being machinery, communication devices, software programs, tools, and so on.